Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

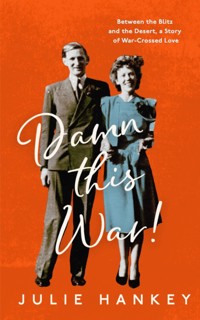

'Moving, funny ... an exquisite story of love, hope, distance and, ultimately, disenchantment.' Mail on Sunday 'A sad and truthful fragment of modern history' TLS 'Beautifully written' Jenny Uglow The love story of Zippa and Tony is nothing without the context of the Second World War. The war introduced them - they met as blackout wardens in London. It gave them darkened streets to wander in, hand in hand, then, by sending Tony away to officer training camps, it sharpened their hunger for each other, casting a glow over his comings and goings. It turned them into schemers and wanglers against fate and army regulations. It pressed them into marriage, and when the war decided to deploy him to North Africa, it whispered the urgent question of a baby. To which Tony, thinking of the war, replied maybe not; and Zippa, thinking of the war, said yes. In spite of themselves, the war experience was changing them both, and yet both were hanging on, looking back, suspended in memory and time, and living from letter to letter. Decades later, their daughter Julie discovered their letters, and piecing them together began to create a portrait of her parents and their relationship that was completely unfamiliar to her. Vivid, honest and completely absorbing, Damn This War! is a true insight into a wartime love story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 420

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in the UK in 2023 byIcon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,39–41 North Road, London N7 9DPemail: [email protected]

ISBN: 9781837730360Ebook ISBN: 9781837730377

Text copyright © 2023 Julie Hankey

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Berling by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK

Contents

Prologue: Zippa and Tony

Chapter 1‘Those golden autumn days’

Chapter 2‘Damn this war’

Chapter 3‘Better not think’

Chapter 4‘Soldier, I wish you well’

Chapter 5‘If I were killed’

Chapter 6‘Millions and millions of flies’

Chapter 7‘Blood and pain’

Chapter 8‘A considerable achievement’

Chapter 9A turning point

Chapter 10‘A lovely ambassadress, darling’

Chapter 11‘Largely centred round Rosalind’

Chapter 12‘She looks like you’

Chapter 13‘To sustain and stimulate guerilla warfare’

Chapter 14‘The mechanics of it’

Chapter 15The soldier’s return

Chapter 16‘My despair is indescribable’

Chapter 17Dreams and shadows

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

For Rosalind

Prologue

Zippa & Tony

It has taken almost a lifetime to be able to stand back from my parents, Zippa and Tony, and to see them as a story. It seems peculiar even to explain my mother’s name – a corruption of Philippa. They were themselves, not ‘characters’ to be interpreted. There were no inverted commas round them. As for their being part of any context, that too feels faintly treacherous. These two were as real and unique to me as the shape of their hands and faces. How could I think of them in relation to history?

But the decades have passed, and the edge has worn off. I’ve opened their letters, mulled them over, and I now surprise myself thinking of them as figures in a frame. Death has helped. They are completed, with a beginning, a middle and an end. But what has tied them off more completely than death is just that overwhelming sense of their context – namely the war. The years from 1939 to 1945 made their story, the whole arc of it. The war introduced them – they met as blackout wardens in London. It gave them darkened streets to wander in, hand in hand, as they searched for chinks of light in the windows. Then, by sending Tony away to officer training camps across England, it sharpened their hunger for each other. It cast a glow over his comings and goings. It turned them into schemers and wanglers against fate and army regulations. It pressed them into marriage, and when the war decided to deploy him to North Africa, it whispered the urgent question of a baby. To which Tony, thinking of the war, replied maybe not; and Zippa, thinking of the war, said yes.

And so to the long separation, he in Egypt, Libya, Tunis and Algeria, she in London and, when the bombing was bad, in Derbyshire where her cousin Betty lived. In spite of themselves, experience was changing them both, and yet both were hanging on, looking back, suspended in memory and time, and living from letter to letter.

When I and my sister were growing up, my mother would tell us stories about the people on her side of the family. We grew up with them, dead or alive, Edwardians and Victorians all jumbled up alongside the moderns. They were like people in a play. We even had some of their clothes in our dressing-up box. We knew too that this family had written to each other constantly, and that our mother had boxes and bags of their letters going back well into the 19th century, stuffed away in drawers and cupboards. When in her last years she became very frail and left her home to come and live with us each in turn (luckily we lived not far from one another), it became a question in our minds – what to do with the letters?

As it happened, I had already by then become interested in my mother’s father, an Egyptological archaeologist well-known in his day. This had been at the prompting, not so much of my mother, as of my mother-in-law, Vronwy Hankey, who was herself a distinguished archaeologist and had come across him quite independently. My mother had therefore given me everything relevant to him and I had used those letters as the basis for a biography. But the question remained – what about the rest, dauntingly untidy and unsorted? Unless we made a bonfire of them, there was nothing for it but to carry them off to my house – my penalty for writing about the archaeologist! – and stuff them away there. Over the coming years, there they sat, a growing reproach, until I turned them into a second book – this time, largely about the women my mother had so often talked of. Then I put everything away and stopped thinking about them.

But there remained at the back of my mind one stubborn and silent bundle. These were the letters that my father had written to my mother during the war. My reaction to them when I had first found them in one of her drawers is perhaps difficult to understand now. My heart had not leapt. The Second World War, the experiences of those who lived through it, the vanishing number of its veterans, are now subjects of great interest. But we as children, born in and soon after the war, had not been brought up to think in this way. It was not that the war was unmentionable. It was just that our parents didn’t speak of it much. My father hardly ever. My mother would tell us a few things, but between themselves they didn’t reminisce. Those who did were called ‘war bores’. So I had not pounced on Tony’s wartime letters with a sense of excitement and discovery. In fact I had given an inward groan. I was reluctant to embark on yet another journey. I took them home and half-forgot them.

My parents died within a few years of each other around the millennium, and a decade or so later, when my sister was approaching her 70th birthday, I wanted to write something for her about her birth and early childhood. I turned to my father’s bundle to see what I could find, opening the letters at about the right dates, dipping and skipping, and not always understanding what I was reading. Still, I found myself more interested, more moved even, than I had expected. The letters were a surprise. I realised that I hadn’t really known my father.

Time passed. I thought I had done with family history. But it wasn’t so easy. There were obstinate things among those wartime letters that wouldn’t lie down – and among other wartime letters too, the ones my mother wrote to her brother. In them, she had spoken of my father, and of their courtship and marriage in a way that had surprised me. Perhaps, after all, I hadn’t really known her either.

It was no good – this stuffing away and half-forgetting. I fished them out, and Tony’s too, and began reading. This time I was caught – and having already pushed the door ajar for my sister, I couldn’t resist giving it a proper shove and walking through.

Chapter 1

‘Those golden autumn days’

When my parents first met in the autumn of 1939, Zippa was 25 and Tony was 21, fresh out of King’s College, Cambridge that very summer. For him, Zippa was simply the most beautiful, graceful, poetic thing that had ever happened to him. It was a coup de foudre, overwhelming for them both: ‘He is a most passionate boy’, Zippa told her brother Alured, then with his regiment in India, ‘so vital and young’, and ‘he loves me so generously that I sometimes wonder whether women can ever know anything about love at all’. In fact, it made her nervous: ‘I feel very tenderly towards him and so hope I never hurt him’.

Tony was a surprise. He stopped her in her tracks. As it happened, he was very good-looking – fine-featured, athletic. But he didn’t invade her heart. Not at first. They had met at Chelsea Town Hall on the King’s Road, just around the corner from where they both lived – she in Oakley Street, and he in Oakley Gardens. They might have passed each other in the street a hundred times already and never known it. Now they were at the Town Hall to volunteer as blackout wardens. With the declaration of war came the immediate fear of night-time bombing. Everyone had to put up black curtains and, at lighting-up time, wardens were sent about the streets in pairs to make sure no chink of light escaped. Somehow Tony and Zippa found each other and set off into the night. More than three years later and thousands of miles away, in the midst of the war in North Africa, Tony could still recall the moment: ‘Do you know Dearest,’ he wrote, ‘almost the first lovely thing that thrilled my senses in you was the smell from your hair those first days I ever knew you in the Town Hall.’

I try to imagine them. Would they have made for the little streets to the north of the King’s Road, up Dovehouse Street, down Sydney Street, house after terraced house, each full of windows and curtains? Or would they have been drawn the other way, towards the Embankment, to lean together on one of the windy bridges over the Thames? During a spell of clear cold nights a few months later, my mother again wrote to her brother in India, describing for him the strangeness of the city he had left behind – the blackout and the barrage balloons that people were just getting used to. ‘London is still astonishing in the black-out,’ she wrote:

Last night there was a curious effect. The new crescent moon was brilliant in a blue sky at dusk and just beside it, one above it and one below, were two black balloons, and a little to the left another stood beside a star. They looked like guardian dragons, or great insects hovering before they pounced – but mostly they looked on guard. And when you turned your head around, other balloons in a darker sky still caught the sun.

It doesn’t sound as though she was looking closely at curtains.

During those early months, before the bombs began to drop, the London blackout felt both sinister and romantic: ‘verdurous and gloomy’, wrote Virginia Woolf on a visit to London, ‘one half expects a badger or a fox to prowl along the pavement’. Country and city drew close, like a ‘reversion to the middle ages’ she thought, ‘with all the space and the silence of the country set in this forest of black houses.’1 On a cheerier note, Londoners took a liking to their new barrage balloons and gave them nicknames: Flossie and Blossom were Chelsea’s two.2 Zippa told Alured about a show that was running that winter which included a sketch about a barrage balloon man, played by a popular comedian of the day, Bobby Howes. He’s ‘very sentimental about his balloon’, she wrote, ‘the great silver thing, with Fred Emney’s head and hands sticking out in front’ – Fred Emney being another much-loved comedian:

Then he says what it’s like up there, and talks of the birds and the clouds and the stillness, and all the time the light is fading and you get the feeling of a clear winter’s evening, and then the balloon begins to swing from one side of the stage to the other, while Bobby Howes croons it to sleep, and the effect is both funny and absolutely charming.

This was the poetry of wartime London, something that Zippa would have seized on to put in a letter to her brother. She never wrote of the other London, which he would have known anyway, the London of sandbags and barbed wire and gas masks – snouted goggles, issued at the time of the Munich crisis the September before. The authorities had long been preparing for war. That very summer, in June 1939, a full-scale civil defence exercise had happened all over Chelsea. The scenario had been high-explosive bombs dropped on nine different places, and all the emergency services had been mobilised. A contemporary historian wrote:

Prompt at 12:30 the sirens sounded over Sloane Square, the traffic stopped, the public moved obligingly into roped-off enclosures to represent the as-yet-unbuilt shelters, and loudspeakers warned that bombers would arrive in eight minutes.

Four hundred air raid wardens were on duty that day. Five thousand children were taken from their schools to railway stations so as to test the evacuation plans. And 200 people from across the country observed the whole performance from the roof of the Peter Jones department store.3

One of those who took part was Frances Faviell, an artist who lived in Cheyne Place, a few minutes’ walk from Oakley Street and Oakley Gardens. In her memoir of the Blitz, she describes lying within chalked lines on the pavement, pretending to be a casualty, while ‘ambulance bells clanged, whistles blew, fire engines raced, rattles sounded’.4 In fact, by her account, the whole thing was a bit of a lark. None of the ordinary residents really believed in it, and there was laughter and jeering among the ‘casualties’ on the pavements. But a little over two months later, at the end of August, she describes another exercise, at night this time – more difficult and dangerous in the blackout. Now it was taken for real. People by then were speaking of war as a certainty. They were stocking up on food. Those who could were leaving town, or sending their children away. Faviell watched them: ‘carloads could be seen, toys, perambulators, dogs, cats, and birds all piled in with them or balanced on top of them’.5 And the railway stations were full of other children, government-organised children, half a million of them from nearly a thousand London schools: ‘weeping children, wailing children, laughing children and bravely smiling white-faced children’.6

There were no children in Zippa’s or Tony’s households, but there were old people. At least, in Zippa’s. In 1939, she was living with her mother, a sister, Veronica, and two ancient ladies, both of them bedridden: a great-aunt Katharine who was confused and senile, and the family’s old nurse Nonie, who had been with them since 1910. How to manage the old ladies in an air raid? It was an impossible thought. Best to leave London altogether, find somewhere to rent in the country, and sublet Oakley Street to friends. At some point that autumn, the five of them moved to an old mill-house in Essex – Watermill House, outside the village of Stansted,* near Bishop’s Stortford. It was farming country, something that Veronica in particular had become interested in. So as soon as they were settled, she enrolled on the local farm as a land girl.

The idea of land girls sounds quaint now, like the old ‘Dig for Victory’ posters – a period touch. But it was serious work. Britain was importing 70 per cent of its food, much of it across the Atlantic where it was at risk of being sunk by German submarines. By the end of 1940, 728,000 tons of it had been lost.7 A Ministry of Food was therefore created whose object was both to ration food, and to increase its production at home. Tens of thousands of acres of grassland were to be ploughed up for crops, and tens of thousands more labourers recruited for the work. But how, when the extra men were joining up? Women were the answer. They had worked as agricultural labourers in 1917, towards the end of the First World War, and so they would in this one. They were issued with uniforms as though they were soldiers – there are lists and illustrations in the Land Girl’s manual:8 breeches, boots, khaki overcoats, brown felt hats, ties in Land Army colours, badges and armlets. Lady Denman, honorary secretary of the Women’s Land Army, even borrowed a Churchillian phrase to make the point: ‘The Land Army fights in the fields. It is in the fields of Britain that the most critical battle of the present war may well be fought and won.’9 Not that Veronica would have felt especially military. In fact the reverse.

The mill house at Stansted

Veronica and Zippa were incurable romantics. They had always had a dreamy hankering for the country and its ways. Woods and fields fill Veronica’s childhood diaries and it would have been the same for Zippa had she kept one. The sisters were very close, only a year apart, and almost twin-like in their sympathies. Years before, in the summer of 1934, when they were nineteen and twenty, the family had been lent a farmhouse in Dorset by an old painter friend – Gilbert Spencer, the brother of Stanley – and they had helped on the local farm, working side by side with the men to bring in the harvest. It had made a deep impression on them, and had sowed the idea in Veronica’s mind of one day becoming a farmer, or at least a farmer’s wife.

Zippa, by contrast, had no such thoughts. Her first love lay elsewhere, in the theatre, acting and dancing, and in a small way she had already made a start. She was a student at the Old Vic for that 1933–34 season and had taken tiny parts in the great Shakespeare productions of the day. She had stood in the wings watching actors such as Edith Evans and Charles Laughton, and had silently prayed, so she told me, for a smile from James Mason. She had been invited back for the following season, but there hadn’t been enough money for the student fees. And so she was now scraping along in a semi-professional way, training herself, taking dance classes, performing in small productions and hoping for work. I have an envelope of references from actors and producers who saw her: ‘she is a person of talent and dramatic promise’ says one; ‘I was carried away by the sincerity of her acting’ says another; ‘how well she interpreted the music … as a dancer on that little stage’. So now from the Stansted mill-house, while Veronica set off for the farm, Zippa would catch the train from Bishop’s Stortford for classes and rehearsals in London, stay with friends, sometimes at Oakley Street itself, and come back every few days.

Veronica (left) and Zippa

And Tony? At the beginning of the war, Tony was a pacifist. Politically, he was of the left. He was not, however, a Communist, which at that time he might easily have been – especially as a Cambridge man. The Marxist historian, Eric Hobsbawm, had been an exact contemporary of his at King’s. Tony knew him a little, and admired him greatly.* But he didn’t agree with him altogether, particularly over Russia. He didn’t see why socialism should be identified with Russia – why, as he put it, it should be ‘Russia’s private property’: ‘Russia as a result of her history must be a socialist dictatorship. I believe that we can be a socialist democracy.’

It was a compromise characteristic of him. By the same token, he wasn’t the kind of pacifist who refused absolutely to take part in the war effort. He joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in Birmingham, to start training there in January 1940. Meanwhile, that autumn, he filled in the time working on a local newspaper in east London, The Hackney Post. But really, whatever else he was doing, Tony’s main object in life was Zippa – in London, at Stansted, wherever, whenever.

It happened that Stansted was particularly beautiful during the freezing winter of 1939–40 – clear skies, frost-furred fields, the grass hung white with spiders’ webs and the sun a red ball sitting low on the horizon. That’s how Zippa described it for her brother in India. Tony stayed there for the whole of the week before Christmas and as they all scoured the fields for holly and ivy, and the house filled up with family and friends, the place began to work on him like a kind of magic theatre. In fact, Zippa’s letter to Alured describes the house that Christmas very much like that, as though it were a stage set:

All the holly trees were so thick with berries that we could pick as much as we wanted, and we stuck it up all along the beams and over the arch in the dining room … I sat for hours staring at the little tree when I’d finished decorating it … the old feeling of magic came over me – it’s like being touched with a wand … Joyce [a painter friend] had made a great garland of ivy which hung diagonally across the ceiling, and another looped across the wall in the alcove … and the archway was picked out with trailing ivy and holly, and all the time we had a huge fire going … well, somehow, what with the holly and the table at an angle with a white cloth and 6 brass candlesticks … and the firelight and the dresser – there was something almost extraordinarily bewitching about the room …

And for Tony, it wasn’t just the room. It was the whole cast. Families, let alone large ones, were a foreign land to him: ‘so new to me’, he remembered later, ‘to be in a house with crowds of people’.

Tony and Zippa with a dog at Stansted

Tony was an only child. Not only that, but he had also experienced little family life beyond his parents. There were uncles and aunts and cousins, at least on his father’s side, but he hardly knew them, nor the grandparents on either side – apart from one very old lady, his mother’s mother, in Heathfield, East Sussex. This absence of family was nothing surprising. Tony’s parents had lived abroad for years both before and after he was born. When he was very little, in the early 1920s, they had been in Tehran where his father, Arthur Moore, was the resident correspondent for The Times. They had then moved to Calcutta (Kolkata) where he became assistant editor and later editor of the most prestigious English-language newspaper in India, the Statesman – a post he held until 1942, when he was eased out for advocating independence and Dominion status for India.

Tony’s father was a brilliant, quarrelsome, and philandering Irishman, enormously vital and attractive. He had made his mark early, as an undergraduate in 1904, when he was elected president of the Oxford Union, and he had done it without being an old Etonian or the son of anyone but an obscure Protestant clergyman, and an Irish one at that. He had then thrown himself into the radical circles of his day, living at Toynbee Hall in the east end of London,* ‘in the company of Oxford friends Beveridge and Tawney’.* At the same time he had been employed as secretary to the Balkan Committee – a body that lobbied the government on the plight of the Christians of Macedonia and other Balkan countries then under Turkish rule.

Arthur Moore, editor of the Statesman (India)

Arthur had a taste for adventure, and in the following years, armed with letters from the British authorities, he travelled the Balkans, riding on horseback through the lawless mountains of Albania where few Europeans had ever penetrated. Albanian brigands, Macedonian village headmen, Turkish administrators, an Orthodox bishop or two, Muslims and Christians – Arthur had sat and smoked and feasted with them all. And all the while, both in the Balkans and, from 1908, in Persia, he had written articles for the press at home about these places and their politics.

Nothing in all this suggests a man ready to fall in love, marry and settle. But in 1913 The Times sent him as their special correspondent to St Petersburg, and there he met Eileen Maillet, secretary to one of the other correspondents. With the kind of timing that their son was to repeat in the next generation, Arthur and Eileen married in 1914, and true to the same pattern, the war sent them in different directions: Arthur to the Balkans again and Salonika, and Eileen to Belgrade as a hospital administrator with a British medical team – where she had her own adventure. When enemy bombs dropped on Belgrade, she joined a column of refugees and walked 400 miles in freezing temperatures over the mountains of Albania to the sea. From there she made her way to Italy and at some point – where and how I don’t know – she and Arthur met again. In May 1918, their son Tony was born in Naples.

Tony once admitted to Zippa that he was ‘no good at families’, and the same could have been said of his parents. Even their little threesome couldn’t be made to stick together for long. In 1925, when Tony was seven, Eileen did what all English families of their class did. She took him to England to start his schooling. But she never went back. Perhaps it was the Calcutta climate. More likely, the marriage. It had not been a success. Eileen was quite unlike her flamboyant husband – a reserved, even withdrawn figure, not unkindly, but rigid and humourless. She was also inclined to depression, and would console herself discreetly (so my mother told me) with a bottle of gin in her bedroom.* She doted on her son.

Tony rarely spoke of his childhood and was always loyal to his mother – ‘such a very good person’ he once wrote to his father, ‘that sometimes I feel guilty that I don’t do more to make her happier’. But he did occasionally let slip a remark which gave the game away. ‘You my darling,’ he once told Zippa, ‘will teach me an awful lot about being happy that I missed when I was young.’ When Zippa met Eileen and observed them together, she saw at once how matters stood. It was simple. ‘He doesn’t love her’, she told Alured.

By contrast, Tony was exhilarated by his father. He didn’t see him often, but when he did, it was a treat. Once, when he was eleven, Arthur took him to Venice – perhaps in the gap between prep school and his next school, Rugby. When, in 1941, Tony heard that his father would be visiting England for a few months, the schoolboy in him burst out: ‘DADDY is coming home’, he told Zippa, ‘I am so thrilled, I know you will like him … he really is awfully nice and tremendous fun’.

Arthur was a natural bon viveur, sociable, generous, extravagant. So was Tony, at least by temperament. But it wasn’t until Cambridge, Zippa told me, that he discovered it in himself. Cambridge was a revelation to him, a breath of freedom, an escape from the gloom and guilt of Eileen. It was talk, ideas, friendship. It was also fun, and a taste of the good things of life: skiing (one winter holiday), 18th-century glass (an early taste), silk shirts and handmade shoes (a generous parental allowance).

And now, Christmas 1939, here he was, landed in the middle of this big, young, attractive family. He ‘adores Veronica’ Zippa told Alured (not, I think, with any anxiety), and Veronica returned the compliment. ‘Beautiful’, was her verdict in her own letter to Alured from Stansted, ‘and he moves gracefully’ – always a plus with my mother’s family. ‘Most awfully nice,’ she went on, ‘just like one of the family. He gets on famously with Denny [the other brother] and makes a fuss of Geraldine [the other sister] and brings out the best in her. Also good with Mother.’

Over the coming years, from wherever he was – in barracks somewhere doing his officer training, or in the desert, Stansted lay like a warm jewel to be turned over and over in his mind. Do you remember, he would ask,

Zippa and her brother Denny

those golden autumn days the first autumn of the war, when I used to come down from London by the early train and do you remember the time I arrived by bicycle for breakfast … All my hundred thousand memories of it are so happy and all because of you, our walks in the evening coming home from harvest, and winter evenings that first winter, and Christmas with you, the happiest I have ever had.

That Christmas, before he left for his ambulance training in Birmingham, Zippa and Tony became lovers. ‘I have lived with him’, wrote Zippa to her brother, using the euphemism of the period. It was inevitable, she said, ‘the most natural thing in the world’.

Tony and Zippa were now a couple. And yet, in spite of themselves, this ‘living’ together shifted the pieces a little. For the first time, they looked at the future. Might she become pregnant? Though they snapped their fingers at convention and respectability, still, unmarried motherhood was a strong taboo. Neither of them knew much about precautions. She consulted a friend. He sent off for a brochure. The question of marriage arose. Their fairy tale began to shade into the ordinary world. As it happened, the whole subject was alive, not to say electric, in the family just then. It was to do with Veronica.

Veronica was a faithful diarist, and had been since her early teens. Her entries for 1938 often mention Jewish refugees among their friends, young men, mostly Austrian, fleeing the Nazi persecutions. One of these was a fiery young Zionist called Israel and her diary records many meals and walks and conversations with him. Halfway through 1938, Veronica’s little exercise book which she used as a diary reaches its last page – and the whole row of little exercise books comes to a stop. The diarist, always so full of description and reflection, even after midnight with eyelids dropping and pencil wandering, falls abruptly silent. Perhaps she gave up keeping a diary. More likely, she destroyed what followed.

Veronica

Zippa told me something, however, though only the barest outline. I understood that the young Zionist and Veronica became lovers, and that she conceived a child by him. He begged her to marry him, to have the child, to adopt the Jewish faith and lead a pioneering life with him in Palestine, as it then was. It was an agonising choice, but in the end, she couldn’t do it. His heart was broken, he left for Palestine and Veronica had an abortion secretly in Paris. The secret was kept even from parts of the family.

So perhaps, after all, the Stansted move was more than an escape from bombs. Perhaps it was a place that gave Veronica peace, away from prying questions. In fact it was soon after, in November 1939, that Zippa reported to Alured that Veronica was well again: ‘It is wonderful to see her looking happy and laughing like her old self.’ But the shadow of her story remained, and it lay across Tony and Zippa now: ‘If I get myself into the same trouble as Baby,’ Zippa wrote again to Alured, using the name the family gave to Veronica, ‘then My God! I don’t know – but fear of that has seemed wrong as a reason to hold back.’*

Reading them now, Zippa’s letters to Alured about herself and Tony are surprising, uncomfortable even. Why tell him about ‘living with’ Tony? She hadn’t known whether to say, she writes, but ‘it makes me much happier to tell you’. Why happier? Was she confessing? Did she want her brother’s approval? Did she need to say, as she does, that it was ‘vastly satisfying’? That Tony looked lovely naked? And that he thought she did too? On the face of it, it seems too much, too intimate, vaguely incestuous even.

Much lies behind Zippa’s letters, a history that she, Veronica and Alured shared and carried with them, one way and another, all their lives. To understand it means going back a bit.

The pool that Tony dived into when he fell in love with Zippa and her family was deeper and more strewn with hidden rocks than he could have known. The family was not only large but complicated in ways that had drawn all the siblings – five altogether, two brothers, and three sisters* – into a tight, almost tribal, circle. And within that circle, there had been – and still was – another one, even closer, consisting of Veronica, Zippa and Alured. This drawing together was the consequence of a precarious and chaotic upbringing by parents who had been too distracted by dramas of their own to notice their children much.

At the heart of it lay Hortense, their beautiful American mother. She was a mystery to her children, as they were to her. Her real companions were books. In every other area she was distant and vague, a graceful drifting figure catastrophically at sea in all practical matters. Her weakest point was money. She spent without a thought. She would sign cheques as though they created the money she filled them in for; and she would borrow as though there were no day of reckoning. Dud cheques and furious tradesmen never ruffled her composure. If her debts became overwhelming, she would smile and even, like the Cheshire cat, disappear. When Veronica and Zippa were seven and eight, she fell into serious debt – hundreds of thousands of pounds in modern money – and sailed for America to visit her family. The visit was meant to be for a few months. But, except for a brief return to collect her eldest daughter, Geraldine, Hortense was gone for two years.

As for their father, another Arthur,* the children hardly knew him. He spent his time tearing his hair out, trying to stave off financial ruin in London where Hortense refused to live, preferring places in and around Oxford. He visited when he could, but otherwise his nose was to the grindstone and what consolation he found was with other women. The marriage staggered on for two decades, during which the children were saved from falling between the cracks only by the energy and devotion of three women: their nurse, Nonie, their paternal grandmother, Mimi and Mimi’s daughter, Geanie, always known to the younger generation as Aunt Jane. These women did what they could, according to their lights, to love, train and civilise the children. But in 1924, when the brothers and sisters were aged between eleven and seventeen, the long, slow car crash came to a juddering stop. Arthur pressed for a divorce and Hortense reluctantly agreed. It took another three years, as was usual then, to reach the conclusion of a decree nisi.*

During the divorce years, Hortense took the children to live in an old mill-house (another mill-house) in Mitcham, just south of London, at that time still a country village. Except for the second son, Denny, whose school and university fees were paid by their grandmother Mimi’s second husband* – always known as Uncle Tony – very little was done to educate them. Alured had received some schooling, but nothing formal after sixteen. As for the girls, only the youngest, Veronica, was given any serious education at all. Of the three, she showed the greatest academic promise, and when she was sixteen or so, a godmother paid for her to attend a school in Paris which had connections to the Sorbonne. There she applied herself in earnest to learning the language and its literature, and to using her diary as a writer herself. But no one thought much about the future of any of the girls, and never spoke to them about university or careers. It was assumed they would be vaguely artistic and – like all girls – get married.

But, out of their parents’ neglect the sisters snatched a semi-wild freedom. The Mitcham mill-house was surrounded by a large garden with a stream running through it. For Veronica, Geraldine and Zippa, this became their world. The boys made them a tree house and they would disappear up into it and read, sometimes forbidden books. They roamed the countryside, took picnics into the woods and, on fine summer nights, slept under the stars. They collected an alternative and multiplying family of animals – dogs, cats, rabbits, mice and a goat called Anne – which they loved with intensity, and buried with ceremony. Their closest ally in some of this was Alured.

Of all the brothers and sisters, Alured had perhaps suffered most from the mess of his parents’ marriage, particularly in relation to his father. Arthur Weigall had originally been an archaeologist living and working in Egypt before the First World War. When that dried up in 1914, he had exploited an extraordinary versatility, turning his hand to all kinds of literary and artistic work. He had designed scenery and composed song lyrics for the London theatres. He had written popular historical biographies, best-selling novels and mass circulation journalism. He had even become involved in early film production. Anything to keep the family afloat.

When Alured was about eight, his father had taken him backstage, and the boy had been smitten: the scenery, the lights, the make-up, the actors, musicians and dancers. In due course, the boy had himself begun to paint and write and show some promise as an actor and dancer. It’s a long story,* but when Alured was about thirteen, he tried to run away to sea and did actually accomplish the first stage of his adventure. His wild plan had been to work his way to India where he would live like Kipling’s Kim and write a great work. The attempt failed, the family was thrown into convulsions, and in the aftermath, Arthur persuaded himself that his son was some kind of a genius. He took the boy out of school, devised a special curriculum, and hired a tutor. It’s hard not to see that, just at the moment when the marriage was foundering, the drowning Arthur clutched at his son as a promise of hope.

For Alured the consequences were disastrous. He spent his youth trying and failing to live up to his father’s expectations. In fact, he never fully recovered from the whole crippling episode. His father died in 1934, bitterly disappointed in him. But at least at Mitcham, with his sisters, Alured found a role. Seven and eight years older than them, he became their idol, their touchstone. There was a hint of the magician about him. He was a storyteller, a spell-binder. He read poetry aloud to them, they read Shakespeare together, he made model theatres and devised dramas. Even his failure was a part of his charm. He was both an odd kind of parent to them and, like them, a child. His kingdom in the attic of the Mitcham house – as far from the adult world below as possible – became a magic place for them. Fourteen-year-old Veronica described in her diary its hypnotic atmosphere:

Up in the loft with Alured’s stove giving off glowing heat … just in a sleepy heat we’d sit … perhaps doing quite nothing or sewing or reading, or Alured reading to us, and the dogs snoring, cats purring. … content is a funny feeling. It starts with a tingling feeling in the chest, which gradually goes to the head, as though it were wine, and the head tingles till it nearly bursts … and you come to yourself with a start when someone’s voice parts, not harshly, the silence. … Silence, in the soft heat and light of the stove, then a voice and the dogs raise their heads, and then let them flop back with a deep outlet of breath. The cat’s purring ceases with a little rumble, and the yellow eyes open, so sleepy that they are watering, and then they close and the faint purring starts, and becomes louder and louder until it alone rules the renewed silence.

The Mitcham years cast a spell on the children. When, as adults, they looked back on them, they remembered chaos and neglect, but also a paradise. The family left in 1930, and not long afterwards, the village was engulfed by London, the mill-house was pulled down and in the garden a factory was built. ‘All over the countryside,’ wrote Veronica in her diary, ‘soon it will be the City of England’. England obliterated; paradise lost. It was the lament of their times – a cry against the ‘red rust’, as E.M. Forster called it, of new brick spreading across the land.*

By the time Tony came on the scene, the relationship between Alured and his sisters had developed and matured. He was still revered by them, but they were also colleagues – he and Zippa particularly. The two of them were now trying to make their way in the world of dance and drama. Alured had performed at the recently established Dartington Festival and in several early television films for the BBC: mime-dance versions of Acis and Galatea (to Handel’s music), Hansel and Gretel and The Pilgrims Progress.* Both had been members of a small troupe run by an Australian dancer and teacher called Margaret Barr, a pupil of the American dancer and choreographer, Martha Graham. Veronica’s 1938 diary frequently records them rushing off to class, rehearsing all evening, and coming home exhausted. As performers and dancers they were equals, watching, judging and analysing each other with sometimes ruthless honesty. Nothing escaped them, either physically or emotionally. In the circumstances, and given their particular and peculiar history, Zippa’s confiding words about her lover were perhaps not so surprising.

But there’s something more. Zippa had, in a sense, been rushed by Tony, and it had frightened her a little. She was fearful that the great hurricane of his love would sweep her from her moorings. Alured and Veronica moored her, Alured in particular, who kept her steady in the work she loved best. Talking to him about Tony as she did was perhaps a way of ‘placing’ him, of cutting him down to size. She was spinning into Tony’s vortex faster than she quite wanted, and she needed to recover herself – her self. As she put it to Alured:

Alured performing with a fellow dancer, Margaret Dale

Last week-end … [Tony] came up here [from his ambulance unit in Birmingham]. He was speechless when he saw me and then he cried. Sometimes I just don’t understand. I love him in a way myself, but it’s not like that … I wonder whether I am a very very selfish person – I suppose it’s really that you and Baby are the only ones that really matter to me. Sometimes I think I could quite easily marry and live in the country and be happy ever after – I could too – then comes something in dancing, in poetry or trying a part that gives me such joy, that is more vital to me than anything else, and I know I shall have to do it.

The Margaret Barr Dance Drama Group. Zippa is in the front row, second left.

________

* Not yet an air base. RAF Stansted was officially opened in 1943.

* Tony once reminded Zippa that she had met him too, early on in the war, in a cafe in Bloomsbury: that ‘odd young man’, he wrote, ‘a sjt in the Education Corps … Eric Hobsbawm was his name’.

* A charity established in 1884 by Christian socialist reformers, Samuel and Henrietta Barnett, to provide welfare assistance and education to the poor. It also offered accommodation to graduate volunteers.

* As he wrote in his (unpublished) Memoirs. William Beveridge, author of the Beveridge Report 1942; R.H. Tawney, social and economic historian and reformer.

* I remember her when I was about five and six in the 50s – a little red in the face with wild grey hair, but more openly affectionate than this picture suggests. Perhaps time and the drink had mellowed her. I remember the Victoria Wine Company shop she would visit on the corner of Oakley Gardens; also, and improbably, accompanying her to the Chelsea Classic cinema to see the latest Gina Lollobrigida films. We must have made an odd couple.

* In a sign of how strong the taboo was, Alured blacked out the words ‘the same’ and ‘as Baby’. But his prying niece has managed to make out the words beneath.

* The brothers were born in 1907 and 1910; the sisters in 1913, ’14, and ’15.

* Arthur Weigall. Both Tony’s and Zippa’s fathers were called Arthur, a popular Tennysonian name in the 1880s when they were born.

* I tell the full story in Kisses & Ink (FeedAread, 2018).

* An Anglican clergyman. Mimi’s first husband had been a soldier, who had died in the 1880 war with Afghanistan.

* I tell it in Kisses & Ink, Chapter 21.

* See the last pages of Howards End (1910).

* However, when war broke out, he refused to join ENSA (the Entertainments National Service Association), fearing the family would think he couldn’t even be a proper soldier.

Chapter 2

‘Damn this war’

In Birmingham, Tony was heartsick – though he was also in luck. The Friends’ Ambulance Unit was set up in the grounds of a mock-Tudor mansion belonging to a Birmingham Quaker family – the Cadburys, philanthropic cocoa and chocolate magnates. As it happened, a godfather of his knew the Cadburys and had written to say Tony was coming. So when the lady of the house, Dame Elizabeth Cadbury, invited the camp commandant to lunch, Tony was included in the party: ‘rather an honour’, he told Zippa, ‘as everyone here seems to worship her.’

She really is perfect, a pile of white hair, thin, erect, with an ebony stick … She has a hand in everything and rules them all. Lunch was good, a great patriarchal table, adoring middle-aged nieces, their husbands and children. She informed me there were 37 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

After that, he was invited to tea by one of the sons, the current managing director of the factory, and had a lovely time at that house too – ‘bristling with every possible luxury’, including a proper bath which they offered him, with bath salts. Tony made friends with his host’s children, two boys of twelve and thirteen, ‘so natural and friendly’, and ‘two sweet little girls, 7 and 3’. The five of them got on famously and Tony was asked to come again the following Sunday.

Now he was back in his hut, lying on his bunk bed, and had decided to cut both supper and prayers so as to use the quiet of his dormitory to write Zippa a long letter. A good fire was roaring in the stove (it was early January) and the few other men around him were also writing. He wanted her to know not only that he loved her, but how he loved her, and all the things she meant to him – her ‘gaiety and courage’, her ‘perfect taste’, and her ‘sense of rightness in things and the proportion of things’: ‘I do really get a feeling of strength and help from you … You are something of which I am absolutely and utterly certain, and I know so surely that you could never be different.’

But then comes this: ‘I don’t think I have ever before in my life had any person except Mummy I suppose, in some ways, from whom I got help. I have been very fond of people and felt that I cared for them and would do a great deal for them, but never that they could really help me.’ He sounds very young – as indeed he was, still only 21. But Zippa might have paused a moment over his remark about ‘Mummy’. Was Tony really looking for a mother, another, better mother? Tony’s ‘I suppose, in some ways’ is rather grudging. Much more fun to have Zippa, with all her gaiety and strength. In fact, Tony himself might have been a little uncomfortable – putting Zippa and his mother into the same sentence. For he quickly goes on to hope that she, in turn, will let him help her:

Darling do let me, because it is never really any good if it is one sided … I am so frightened sometimes of your self reliant side … you make me so happy and I rely on you so much and care so terribly terribly that it should be alright and that I should be able to do and be the things you want.

What exactly he thought she wanted him to do and be, let alone what he himself wanted to do and be, is left hanging. The truth was, he had no idea. The war had claimed him before he had experienced anything much beyond university. All through the war years he would wonder what he was good at. He had no particular wish (or so he said) for much more than a ‘sufficiency’ of money – just ‘an opportunity to have some little influence on things for good rather than ill’. At different times he thought he might be a journalist (like his father), or a teacher, a farmer maybe (like Veronica?), a businessman (not often), something in politics. Thinking perhaps of Zippa and Alured and the people they knew, he once warned her that he didn’t think he was an artist of any kind.