Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

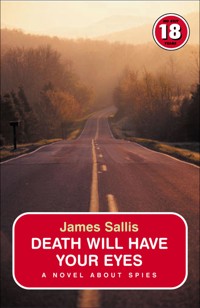

'I drive. That's what I do. All I do.' 'Much later, as he sat with his back against an inside wall of a Motel 6 just north of Phoenix, watching the pool of blood lap toward him, Driver would wonder whether he had made a terrible mistake. Later still, of course, there'd be no doubt. But for now Driver is, as they say, in the moment. And the moment includes this blood lapping toward him, the pressure of dawn's late light at windows and door, traffic sounds from the interstate nearby, the sound of someone weeping in the next room....' Thus begins Drive, a new novella by James Sallis. Set mostly in Arizona and L.A., the story is, according to Sallis, "...about a guy who does stunt driving for movies by day and drives for criminals at night. In classic noir fashion, he is double-crossed and, though before he has never participated in the violence ('I drive. That's all.'), he goes after the ones who doublecrossed and tried to kill him."

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 153

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘I drive. That’s what I do. All I do.’

‘Much later, as he sat with his back against an inside wall of a Motel 6 just north of Phoenix, watching the pool of blood lap toward him, Driver would wonder whether he had made a terrible mistake. Later still, of course, there’d be no doubt. But for now Driver is, as they say, in the moment. And the moment includes this blood lapping toward him, the pressure of dawn’s late light at windows and door, traffic sounds from the interstate nearby, the sound of someone weeping in the next room….’

Thus begins Drive, a novel by James Sallis. Set mostly in Arizona and LA, the story is, according to Sallis, ‘about a guy who does stunt driving for movies by day and drives for criminals at night. In classic noir fashion, he is double-crossed and, though before he has never participated in the violence (‘I drive. That’s all.’), he goes after the ones who double-crossed and tried to kill him.’

PRAISE FOR JIM SALLIS

‘Sallis creates vivid images in very few words and his taut, pared-down prose is distinctive and powerful. The result is a small masterpiece.’ - Sunday Telegraph

‘Sallis is a wonderful writer, dark, lyrical and compelling’ - Andrew Taylor, Spectator

‘Sallis’s lean mystery and flat-voiced prose are refreshing, even startling. A lovely piece of work.’ - Paul Skenasy, Washington Post Books World - Best Books of 2005

‘a minor masterpiece… minimalist, stylish, and all the more evocative for it. Essential noir existentialism.’ - Maxim Jakubowski, Guardian

‘Sallis’s spare, concrete prose achieves the level of poetry’ - Julia Handford, Telegraph

‘James Sallis has written a perfect piece of noir fiction.’ - Marilyn Stasio, New York Times

‘Full throttle getaway to the underworld’ - Lesley McDowell, Independent on Sunday

‘Drive is a sublime read, its detached nature reeling you in from the very first page’ - Marty Mulrooney, Alternative Magazine Online

‘A taut page-turner. Sallis’ lean tale (158 pages) and flat-voiced prose are refreshing, even startling…It’s a lovely piece of work that makes you wish some other writers would take lessons from him.’ - Paul Skenazy, Washington Post

‘The novel is a terrific ride, and true to form, Sallis leaves us with an enigmatic teaser of an ending.’ - Scott M Morris, Los Angeles Times

‘Fast cars, guns and babes. Just my cup of tea’ - Mark Timlin, Independent Online

‘Imagine the black heart of Jim Thompson beating in the poetic chest of James Sallis and you’ll have some idea of the beauty, sadness and power of Drive’ - Dick Adler, Chicago Tribune

‘Stunning’ - Cathy Staincliffe, Tangled Web

‘a compact, beautifully written little noir gem…’ - Seattle Times

‘masterfully convoluted neo-noir, which ranges from the dive bars and flyblown motels of Los Angeles to seedy strip malls dotting the Arizona desert…’ - Publishers Weekly

Drive

James Sallis

www.noexit.co.uk

To Ed McBain,

Donald Westlake and

Larry Block—

three great American writers

Drive

Contents

Chapter One

Much later, as he sat with his back against an inside wall of a Motel 6 just north of Phoenix, watching the pool of blood lap toward him, Driver would wonder whether he had made a terrible mistake. Later still, of course, there’d be no doubt. But for now Driver is, as they say, in the moment. And the moment includes this blood lapping toward him, the pressure of dawn’s late light at windows and door, traffic sounds from the interstate nearby, the sound of someone weeping in the next room.

The blood was coming from the woman, the one who called herself Blanche and claimed to be from New Orleans even when everything about her except the put-on accent screamed East Coast—Bensonhurst, maybe, or some other far reach of Brooklyn. Blanche’s shoulders lay across the bathroom door’s threshold. Not much of her head left in there: he knew that.

Their room was 212, second floor, foundation and floors close enough to plumb that the pool of blood advanced slowly, tracing the contour of her body just as he had, moving toward him like an accusing finger. His arm hurt like a son of a bitch. This was the other thing he knew: it would be hurting a hell of a lot more soon.

Driver realized then that he was holding his breath. Listening for sirens, for the sound of people gathering on stairways or down in the parking lot, for the scramble of feet beyond the door.

Once again Driver’s eyes swept the room. Near the half-open front door a body lay, that of a skinny, tallish man, possibly an albino. Oddly, not much blood there. Maybe blood was only waiting. Maybe when they lifted him, turned him, it would all come pouring out at once. But for now, only the dull flash of neon and headlights off pale skin.

The second body was in the bathroom, lodged securely in the window from outside. That’s where Driver had found him, unable to move forward or back. This one had carried a shotgun. Blood from his neck had gathered in the sink below, a thick pudding. Driver used a straight razor when he shaved. It had been his father’s. Whenever he moved into a new room, he set out his things first. The razor had been there by the sink, lined up with toothbrush and comb.

Just the two so far. From the first, the guy jammed in the window, he’d taken the shotgun that felled the second. It was a Remington 870, barrel cut down to the length of the magazine, fifteen inches maybe. He knew that from a Mad Max rip-off he’d worked on. Driver paid attention.

Now he waited. Listening. For the sound of feet, sirens, slammed doors.

What he heard was the drip of the tub’s faucet in the bathroom. That woman weeping still in the next room. Then something else as well. Something scratching, scrabbling…

Some time passed before he realized it was his own arm jumping involuntarily, knuckles rapping on the floor, fingers scratching and thumping as the hand contracted.

Then the sounds stopped. No feeling at all left in the arm, no movement. It hung there, apart from him, unconnected, like an abandoned shoe. Driver willed it to move. Nothing happened.

Worry about that later.

He looked back at the open door. Maybe that’s it, Driver thought. Maybe no one else is coming, maybe it’s over. Maybe, for now, three bodies are enough.

Chapter Two

Driver wasn’t much of a reader. Wasn’t much of a movie person either, you came right down to it. He’d liked Road House, but that was a long time back. He never went to see movies he drove for, but sometimes, after hanging out with screenwriters, who tended to be the other guys on the set with nothing much to do for most of the day, he’d read the books they were based on. Don’t ask him why.

This was one of those Irish novels where people have horrible knockdowndragouts with their fathers, ride around on bicycles a lot, and occasionally blow something up. Its author peered out squinting from the photograph on the inside back cover like some life form newly dredged into sunlight. Driver found the book in a second hand store out on Pico, wondering whether the old-lady proprietor’s sweater or the books smelled mustier. Or maybe it was the old lady herself. Old people had that smell about them sometimes. He’d paid his dollar-ten and left.

Not that he could tell the movie had anything to do with this book.

Driver’d had some killer sequences in the movie once the hero smuggled himself out of Northern Ireland to the new world (that was the book’s title, Sean’s New World), bringing a few hundred years’ anger and grievance with him. In the book, Sean came to Boston. The movie people changed it to L.A. What the hell. Better streets. And you didn’t have to worry so much about weather.

Sipping at his carryout horchata, Driver glanced up at the TV, where fast-talking Jim Rockford did his usual verbal prance-and-dance. He looked back down, read a few more lines till he fetched up on the word desuetude. What the hell kind of word was that? He closed the book and put it on the nightstand. There it joined others by Richard Stark, George Pelecanos, John Shannon, Gary Phillips, all of them from that same store on Pico where hour after hour ladies of every age arrived with armloads of romance and mystery novels they swapped two for one.

Desuetude.

At the Denny’s two blocks away, Driver dropped coins in the phone and dialed Manny Gilden’s number, watching people come and go in the restaurant. It was a popular spot, lots of families, lots of people if they sat down by you you’d be inclined to move over a notch or two, in a neighborhood where slogans on T-shirts and greeting cards at the local Walgreen’s were likely to be in Spanish.

Maybe he’d have breakfast after, it was something to do.

He and Manny had met on the set of a science fiction movie in which, in one of many post-apocalypse Americas, Driver had command of an El Dorado outfitted to look like a tank. Wasn’t a hell of a lot of difference in the first place, to his thinking, between a tank and that El Dorado. They handled about the same.

Manny was one of the hottest writers in Hollywood. People said he had millions tucked away. Maybe he did, who knew? But he still lived in a run-down bungalow out towards Santa Monica, still wore T-shirts and chinos with chewed-up cuffs over which, on formal occasions such as one of Hollywood’s much-beloved meetings, an ancient corduroy sports coat worn virtually cordless might appear. And he was from the streets. No background to amount to anything, no degree. Once when they were having a quick drink, Driver’s agent told him that Hollywood was composed almost entirely of C+ students from Ivy League universities. Manny, who got pulled in for everything from script-doctoring Henry James adaptations to churning out quickie scripts for genre films like Billy’s Tank, kind of put the lie to that.

His machine picked up, as always.

You know who this is or you wouldn’t be calling. With any luck at all, I’m working. If I’m not—and if you have money for me, or an assignment—please leave a number. If you don’t, don’t bother me, just go away.

“Manny,” Driver said.“You there?”

“Yeah. Yeah, I’m here… Hang a minute?… I’m right at the end of something.”

“You’re always at the end of something.”

“Just let me save… There. Done. Something radically new, the producer tells me. Think Virginia Woolf with dead bodies and car chases, she says.”

“And you said?”

“After shuddering? What I always say. Treatment, redo, or a shooting script? When do you need it? What’s it pay? Shit. Hold on a minute?”

“Sure.”

“… Now there’s a sign of the times. Door-to-door natural-foods salesmen. Like when they used to knock on your door with half a cow butchered and frozen, give you a great deal. So many steaks, so many ribs, so much ground.”

“Great deals are what America’s all about. Had a woman show up here last week pitching tapes of whale songs.”

“What’d she look like?”

“Late thirties. Jeans with the waistband cut off, faded blue workshirt. Latina. It was like seven in the morning.”

“I think she swung by here, too. Didn’t answer, but I looked out. Make a good story—if I wrote stories anymore. What’d you need?”

“Desuetude.”

“Reading again, are we? Could be dangerous… It means to become unaccustomed to. As in something gets discontinued, falls into disuse.”

“Thanks, man.”

“That it?”

“Yeah, but we should grab a drink sometime.”

“Absolutely. I’ve got this thing, which is pretty much done, then a polish on the remake of an Argentine film, a day or two’s work sprucing up dialog for some piece of artsy Polish crap. You have anything on for next Thursday?”

“Thursday’s good.”

“Gustavo’s? Around six? I’ll bring a bottle of the good stuff.”

That was Manny’s one concession to success: he loved good wine. He’d show up with a bottle of Merlot from Chile, a blend of Merlot and Shiraz from Australia. Sit there in the wardrobe he’d paid out maybe ten dollars for at the nearest second hand store six years ago and pour out this amazing stuff.

Even as he thought of it, Driver could taste Gustavo’s slow-cooked pork and yucca. That made him hungry. Also made him remember the slug line of another, far classier L.A. restaurant: We season our garlic with food. At Gustavo’s, the couple dozen chairs and half as many tables had set them back maybe a hundred dollars total, cases of meat and cheese sat in plain view, and it’d been a while since the walls got wiped down. But yeah, that pretty much said it. We season our garlic with food.

Driver went back to the counter, drank his cold coffee. Had another cup, hot, that wasn’t much better.

At Benito’s just down the block he ordered a burrito with machaca, piled on sliced tomatoes and jalapenos from the condiment bar. Something with taste. The jukebox belted out your basic Hispanic homeboy music, guitar and bajo sexto saying how it’s always been, accordion fluttering open and closed like the heart’s own chambers.

Chapter Three

Up till the time Driver got his growth about twelve, he was small for his age, an attribute of which his father made full use. The boy could fit easily through small openings, bathroom windows, pet doors and so on, making him a considerable helpmate at his father’s trade, which happened to be burglary. When he did get his growth he got it all at once, shooting up from just below four feet to six-two almost overnight, it seemed. He’d been something of a stranger to and in his body ever since. When he walked, his arms flailed about and he shambled. If he tried to run, often as not he’d trip and fall over. One thing he could do, though, was drive. And he drove like a son of a bitch.

Once he’d got his growth, his father had little use for him. His father had had little use for his mother for a lot longer. So Driver wasn’t surprised when one night at the dinner table she went after his old man with butcher and bread knives, one in each fist like a ninja in a red-checked apron. She had one ear off and a wide red mouth drawn in his throat before he could set his coffee cup down. Driver watched, then went on eating his sandwich: Spam and mint jelly on toast. That was about the extent of his mother’s cooking.

He’d always marvelled at the force of this docile, silent woman’s attack—as though her entire life had gathered toward that single, sudden bolt of action. She wasn’t good for much else afterwards. Driver did what he could. But eventually the state came in and prised her from the crusted filth of an overstuffed chair complete with antimacassar. Driver they packed off to foster parents, a Mr. and Mrs. Smith in Tucson who right up till the day he left registered surprise whenever he came through the front door or emerged from the tiny attic room where he lived like a wren.

A few days shy of his sixteenth birthday, Driver came down the stairs from that attic room with all his possessions in a duffel bag and the spare key to the Ford Galaxie he’d fished out of a kitchen drawer. Mr. Smith was at work, Mrs. Smith off conducting classes at Vacation Bible School where, two years back, before he’d stopped attending, Driver had consistently won prizes for memorizing the most scripture. It was midsummer, unbearably hot up in his room, not a lot better down here. Drops of sweat fell onto the note as he wrote.

I’m sorry about the car, but I have to have wheels.

I haven’t taken anything else. Thank you for taking

me in, for everything you’ve done. I mean that.

Throwing the duffel bag over the seat, he backed out of the garage, pulled up by the stop sign at the end of the street, and made a hard left to California.

Chapter Four

They met at a low-rent bar between Sunset and Hollywood east of Highland. Uniformed Catholic schoolgirls waited for buses across from lace, leather and lingerie stores and shoe shops full of spike heels size fifteen and up. Driver knew the guy right away when he stepped through the door. Pressed khakis, dark T-shirt, sport coat. De rigueur gold wristwatch. Copse of rings at finger and ear. Soft jazz spread from the house tapes, a piano trio, possibly a quartet, something rhythmically slippery, eel-like, you could never quite get a hold on it.

New Guy grabbed a Johnny Walker black, neat. Driver stayed with what he had. They went to a table near the back.

“Got your name from Revell Hicks.”

Driver nodded.“Good man.”

“Getting harder and harder all the time to step around the amateurs, know what I’m saying? Everybody thinks he’s bad, everybody thinks he makes the best spaghetti sauce, everybody thinks he’s a good driver.”

“You worked with Revell, I have to figure you’re a pro.”