6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

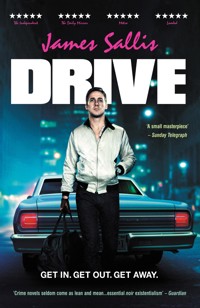

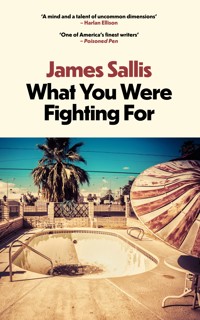

WHAT YOU WERE FIGHTING FOR is a wonderful collection of short stories that provokes the mind with its weird and intriguing tales. We catch glimpses of worlds that are similar to our own, but always different enough to make you wonder and sit at the edge of your seat. Reading this collection you often have to work out what is truly happening as Sallis weaves his imaginative portrayals of idiosyncratic characters with all the subtlety of the mind that spawned the Lew Griffin novels, Willnot, Sarah Jane, and Drive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY!

Sign up for all the latest crime and thriller

news and get free books and exclusive offers.

BEDFORDSQUAREPUBLISHERS.CO.UK

Praise for James Sallis

‘One of America’s finest writers’ Poisoned Pen

‘James Sallis is a superb writer’ Times

‘A mind and a talent of uncommon dimensions’ Harlan Ellison

‘Sallis is an unsung genius of crime writing’ Independent

‘Poetic storytelling of the highest quality, entrancing and yet utterly unexpected’ Daily Mail

‘Sallis is a fastidious man, intelligent and widely read. There’s nothing slapdash or merely strategic about his work… peculiar and visionary’ Iain Sinclair, London Review of Books

‘Sallis’s lean mystery and flat-voiced prose are refreshing, even startling’Paul Skenesay, Washington Post Best Books of the Year

‘Sallis creates vivid images in very few words and his taut, pared-down prose is distinctive and powerful. The result is a small masterpiece’Susanna Yager, Sunday Telegraph

The title of this book is in homage to and

the book is dedicated to the memory of

Theodore Sturgeon

HOW THE DAMNED LIVE ON

The closest I can come to the giant spider’s name is Mmdhf. She loves to talk philosophy. How we become what and who we are, why we are here, the influence of the island’s isolation on what we believe. She waits for me each morning on the beach. As I approach along the steep, snaking path from the cave, I imagine paper cups of coffee at the end of two of her arms. They steam in the early morning chill.

‘You slept well?’ she asks.

‘I did.’ I tell her about the dreams. In the latest versions I find myself lost on the streets of a teeming city. No one will respond to my pleas for help. Then I ask: ‘Do you dream?’

‘Another of your difficult questions. We sleep, and live within the sleep. Perhaps we – my kind, I mean – fail to differentiate between the two lives.’

Pirates come in the night and carry off all our things: spare clothing and blankets, the crate of fig preserves, sharp knives, our half-built raft. Later we see they have used material from the last to repair the deck and railings of their ship.

There are flowers and plants here like none we have ever seen, vast thickets of them awash with colors one might more reasonably anticipate finding in tropical climes, some of the flowers aloft on stems high above our heads. Cook fears one of the lesser plants. He insists that they uproot themselves and move around at night, that he lies awake listening to the soft pad of their rootsteps. Anything is possible, the Professor responds.

They are both wrong, I hope.

Ahmad meanwhile is at wit’s end. He does not know in what direction Mecca might be.

• • •

Captain stands for hours at a time, statue-like, alone on the open beach where we washed ashore, sextant aimed to the heavens. He has long ago given up on his charts. They lie abandoned in a far recess of the cave. Increasingly, when we speak to him his replies seem insensible.

I ask Mmdhf one morning the name of the island, what she calls this, her home. Thoughtfully she speaks the word in her language, a long word that rolls on and on in her barbed, glistening mouth. It might best be translated, she tells me, as This Place.

The pirates, it appears, have mutinied, discharging their captain, complete with parrot, onto the island. The parrot and Mmdhf have become close. They sit all afternoon beneath a favored banyan tree talking. I am beginning to feel, as I suspect the pirate captain must, jealous.

Each incoming wave washes tiny, fingernail-sized crabs onto the shore, dozens of them. They weigh almost nothing, what a heavy breath weighs, perhaps. Their shells and flesh are transparent. As the water recedes they take their bearings, right themselves, and scuttle toward the sea. A few make it. Most are driven back onto the shore by the next wave.

Long ago Mmdhf explained to me how so many of her children had died, all of them actually, and that this is what brought her to a deeper thinking. It was then (how had I not known this before?) that I understood she was the last and only one of her kind.

Our subsistence, the subsistence of most all the island’s life forms, depends upon a fruit we call Tagalong, which also serves as substitute womb for the island’s most common insect, a horned, armored species resembling a cigar that has sprouted legs. These lay their eggs in the Tagalong. Commonly one bites into the fruit to discover a larval head peering out.

Tagalong grows most abundantly toward the center of the island – due, the Professor says, to the dormant volcano there, its creation of a temperate zone. For the same reason, and for ready access to quantities of Tagalong, birds flock to the area in vast numbers. Of late, birds have begun to move away. This suggests, the Professor tells us, that the volcano is about to erupt.

The parrot agrees.

Mmdhf and I have spoken daily for months when I come to realize that I find something in her speech unsettling. Her enunciation is perfect, her word choice spot on; she speaks without appreciable accent and with proper inflection. Yet something nips at the heels of our dialogues. My uneasiness, I decide at length, lies in subtle shadings of verb choices.

Is it possible, I ask one morning, that we experience time differently?

‘As in our earlier discussion of dream and waking,’ she replies, ‘yes. And you cannot imagine how surprised I was to learn that time for your kind is not continuous but sequential.’

‘But if continuous, how can there be said to be time at all?’

‘This.’ She turns her head, pauses, turns back. ‘Change.’

‘If all time is one…’ I hesitate, groping for the question, ‘… then you know the future, you know what will happen.’

‘Yes.’ She lifts two legs, as I have seen her do only once before, when she spoke of her children. ‘I miss you.’

MISS CRUZ

I think I always knew I didn’t fit in. I’d look around at the families, their dogs and bikes and travel trailers, parents hopscotching cars out of the driveway every morning to go to work, and knew I’d never be a part of that. Most of us feel that way, I guess, when we’re young. But with me it wasn’t a matter of feeling. I knew.

The other thing I knew was that I needed secrets, needed to know things others didn’t, have keys to doors that stayed locked a lot. When I was a kid, for two years all I could think or read about was magic tricks, this arcane stuff no one knew much about. Thurston’s illusions, Chung Ling Soo, Houdini. Sleight of hand and parlor magic and bright lacquered cabinets. Read every book in the library, spent the little money I had on a subscription to a slick magazine named Genie out of LA. Later it was Hawaiian music (can’t remember how that got started), then nineteenth-century clocks. I was looking, you see, looking for stuff other people didn’t know, looking for secrets. They were as essential to me as water and the air I breathed.

One thing I didn’t know was that I’d wind up here in this desert, where it looks, as someone told me when I first came, like God squatted down, farted, and lit a match to it. Long way from the hills and squirrel runs I grew up in. Everything low and spread out, duncolored and difficult. But hey, you want to build this big-ass city, how much better could you do than smack in a wasteland where it’s a hundred degrees three months out of the year and water, along with everything else, has to be trucked in?

But cities are like lives, I guess, when we start out we never know what they’re going to turn into. So here I am, living in what’s politely termed a residential hotel on the ass-end side of Phoenix, Arizona, with half a dozen T-shirts, two pair of jeans, a week’s worth of underwear if I don’t leak too much, some socks, a razor and a toothbrush. Oh – and a four-thousand-dollar guitar. It’s a Santa Cruz, black as night all over, not even any fret markers on her. Small, but with this huge sound.

Because I’m a musician, see. Have the black suit, white shirt and tie to prove it. They’re all tucked into one of those dry-cleaner bags in the back of what passes for a closet here. It’s the size of a coffin; at night I hear things with bristly legs moving around in there. Outside the closet, there’s half of what began life as a bunk bed, a table whose Formica top has a couple of bites out of it, two chairs, and a dresser with a finish that looks like maple candy.

And the guitar case, of course, all beat to hell. Same case I’ve had all along, came with the Harmony Sovereign I found under the bed in a rented room back in Clarksdale, Mississippi, around 1980, when it all started. Second one, a pawnshop guitar, didn’t have a case, so I kept this one, and after that… well, not much history or tradition in my life, you work with what you have. Been a lot of guitars in there since. Couple of J-45s, an old small-body Martin, a Guild archtop, Takamines, a Kay twice as old as I am. Really get some looks when I pull this gorgeous instrument out of that case. Books and covers, right?

I forgot to mention the stains on ceiling and mattress. Lot of similarities among them; I know, I’ve spent many a night and long afternoon sandwiched between, mattress embossed with personal stories, all those who fell to earth here before me, stains on the ceiling more like geological strata, records of climate changes, weather, cold winters and warm.

It’s not a big music town, Phoenix. Mostly a big honking pool of headbangers and cover bands, but there’s work if you’re willing. What do I play? Like Marlon Brando in The Wild One said when asked what he was rebelling against: What do you have? Mariachi, Beatles tributes, polka, contra, happy-hour soft jazz – I’ve done it all. Even some studio work. But my bread and butter’s country. Kind of places you find an ear under one of the tables as you’re getting the guitar out of the case and the bartender tells you good, they’ve been looking for that, got torn off in a fight last weekend.

Those gigs, mostly Miss Cruz stays in the case, right there by me all night, and I play a borrowed Tele that belongs to… I started to say a friend, but that’s not right. An associate? Man doesn’t play, but he has this room with thirty or more guitars, all top drawer, and humidifiers pouring out fog everywhere so you go in there it’s like stepping into a rain forest, you keep expecting parrots to fly out of the soundholes. Jason Fletcher. We work together sometimes. Secrets, remember? And he’s a lawyer.

Thing is, musicians get around, hear things. We’re on the street, out there wading in the sludge of the city’s bloodstream. And we’re like furniture in the clubs, no one thinks we’re listening or paying attention or give half a damn. Plus, we get to know the barkeeps and beer runners, who see and hear more than us.

So I do a little freelance work for Jason sometimes. Started when he came by Bad Mojo down on the lower banks of McDowell looking for a client of his who owed him serious money and caught me with a pick-up band playing, of all things, Western Swing. Strong bass player/singer, solid drummer, steel player who’d been at it either two weeks or forty years, hard to tell. Anyhow, Jason and I got to talking on a break and he said how he’d always wanted to play like that and wanted to know if I gave lessons. People are coming up to you all the time at gigs and asking that, so I didn’t think much of it, but a few days later, comfortably late in the morning, my phone rang. After work that day he swung by, and when he opened up the case he was carrying, there was a kickass old Gibson hollowbody.

The lesson lasted about twenty minutes before dissolving into gearhead chatter. Man could barely play a major scale or barred minor chord, but he knew everything about guitars. Woods, inlay, model designations, who made what for whom, Ditson, Martin, the Larsons, Oscar Schmidt – had it all at his fingertips, everything but music.

‘Were you mathematically inclined as a child?’ I remember he asked. It was a question I’d heard before and, knowing where he was taking it, I said no, it’s just pattern recognition: spatial relationships, forms. That musicians, all artists, are just compulsive patternmakers at heart.

And like with music, you stay loose, follow where life takes you. You’ve got the head, the changes, but the tune’s what you make of it, you find out what’s in there. So when the lesson dismembered itself we went out for a beer and went on talking and the rest just kind of developed from there. He’d say keep an ear out for this or that, or once in a while something would drift my way that had a snap to it and I’d pass it along.

For the rest, I have to go back a year or so.

It’s a breezy, cold spring and I’m sitting in the outdoor wing of a coffeehouse with half an inch left in my cup for the last half hour looking over at the café next door, Stitches, a frou-frou place heavy on fanciful salads and sandwiches. There’s a waitress over there that just looks great. Nothing glamorous or even pretty about her, plain, really, a summer-dress kind of girl, but these sad, unguarded eyes and, I don’t know, a presence. Also an awkwardness or hesitancy. She’ll stall out by a table sometimes. Or you look over and she’s just standing there – on pause, like, holding a plate or a rag or the coffee.

There are all kinds of ways of knowing things, and in the weeks I’ve been watching, it’s become obvious that she and the manager are down. Nothing in the open, but lots of small tells for the watchful: their faces when they talk to one another, the way their bodies kind of bend away from one another when they pass, occasional glances into the relic’d mirrors set up like baffles all through the café.

Secrets. Things others don’t know.

And in the past few days it’s become just as obvious that it’s over. They’ve had The Talk. She stalls out more often, gets orders wrong, forgets refills and condiments.

So, lacking much of an attention span and with a loose-limbed hold on reality, I’m sitting there, looking over, thinking how great it would be if she went calmly to the cooler behind the counter, grabbed a pie, walked up to him, and let him have it. Everyone over there in Stitches is staring. And the manager is standing stock still with meringue and peaches dripping off his nose.

All at once then I come to, back to my surroundings, to realize that I’m witnessing, with a half-second delay, exactly what I’ve been picturing in my mind.

Now that’s interesting.

Sweat runs down my back as I wonder how far I can take this.

One of the other waitresses runs into the kitchen, comes back with a can of whipping cream, and lets him have it in the face, right there by the peaches. A few customers look upset, but most are laughing. The cooks come out, stand around him, and sing Happy Birthday. Then I have everybody hold still, like a picture’s just been taken, then they move, then I stop them again, another picture.

Cool.

Then I get scared and bolt.

That night at a club called Tip’s I sat down with my guitar and ran an E chord into an A as many ways as I could think of all over the neck, but that was it. After fifteen or twenty minutes, without saying anything, I put the guitar back in its case and left. Didn’t play for weeks, didn’t go out in public at all, really, just hung in my room. The pictures of those people in the restaurant doing what I was imagining in my mind, exactly what I was imagining in my mind, those stayed with me. But like pictures on a wall, eventually you get used to them, stop seeing them when you walk past. So after a while I eased on back into the world. I’d like to say I was strong enough or scared enough never to repeat the incident, never to take that song for another ride, but of course I wasn’t.

Miss Cruz came to live with me not long after that. She wasn’t happy where she was – a common story: unloved and unappreciated, neglect, abuse – and where he is, he has no need for her. His needs are pretty simple. They change the catheter every few days, squirt stuff in his eyes to keep them from drying out. I went there once to visit. Keep telling myself I didn’t put him there, his own choices did – and that night he decided to beat up on his woman in the bar where I was playing.

This entire aspiring society, humankind itself, is built and maintained on violence. We all know that, but pretend we don’t. What matters is when and against whom you let the dogs out, right?

So back now to Jason Fletcher, who’d shown up weeks before at a wine bar where I was playing a solo early-evening gig to tell me the sheriff’s office was harassing his client and he’d appreciate my keeping ears open for anything that might help. Sheriff Jack Dean, a stump-legged rind of a man with a bad comb-over, long history of marginally legal activity, and continuous re-election by preying on fear. Fletcher’s client had written an elaborately researched, clear-eyed series about him for the Republic and now found himself followed by unmarked cars wherever he went. Waiting outside his house in the morning, parked across from the coffee shop where he stopped on the way to work.

‘These boys are slick from years of practice,’ Fletcher said, ‘they’ve got it down to a fine art. No marks, no bruises.’

What came to me, what I picked up off the forest floor, wasn’t all that much, but it worked. The guy was able to drink his coffee in peace, rumors of lawsuits and worse evaporated, no more was heard of the ‘inquiry’ that had sheriff’s men knocking on neighbor’s doors.

It haunted me, after. I looked up the journalist’s series in the Republic, read every word and climbed over every comma twice. Dropped in with ears open at a downtown bar frequented by cops. Understand, I’m not the kind ever to pay much heed to politics. Never thought about how rotten the whole thing was, or much cared. And if I did, simply assumed that corruption and greed had to be the universal standard. It’s politics, right? And politics is about power, so how else could it be played? As for me, I just wanted to be left alone, to play my guitar, make music. But that whole sheriff thing wouldn’t let go of me, kept nipping at my heels, pissing on my shoes. Who can say why it is some things stick to us? I’d be sitting in OK Coffee or 5&10 Diner, see a county car pull in, or some beat-up dude staggering by outside, and it would all start back up.

Something growing in the dark within me.

Then one night it’s 4 a.m. after a free-jazz gig with a sax player, music with a lot of anger inside, and the anger comes home with me. One of those nights when moonlight’s spilling everywhere, then clouds slide in and it goes dark. No wind, no breeze – like the world’s stopped breathing. Neighbors somewhere playing what sounds like Texas conjunto on the radio. I’m rattling around the room like always after gigs, drained and dog-tired but still wired, cranked up to the very edge, when there’s a change in the light, a flicker, and I look up at the TV. I’ve had it on with no sound, silent company in the night. Breaking News, the screen reads now. I turn up the sound.

There’s been a huge raid on a houseful of illegals out near the county hospital. Clips show a dozen or more half-dressed adults and kids being loaded into vans. Peace officers and TV crew outnumber them three to one. Lights worthy of a movie set. Then a cut – live! – to the man himself, Sheriff Jack, at his desk, American flag at parade rest behind him. Hard at the helm even at this hour, working as ever (he tells us) to uphold the laws of the land, serve the good people of Maricopa County, defend every border, and keep us all safe.

Not a single word about profiling, illegal traffic stops, unwarranted search and seizure, rampant intimidation, financial irregularities, or the ongoing federal investigation of his department.

As he speaks, he touches his nose again and again, age-old tell of the liar. Third or fourth time, he takes the finger away, looks at it a moment, and sticks it in his nose. He’s digging around in there. Still talking, talking, talking.

And I realize that what I just saw, the nose touch, the nose pick, I pictured in my mind half a moment before it happened.

Sheriff Jack pulls the finger out, examines it, and tries the other nostril.

I’m thinking okay, so I don’t have to be there, looks like I just have to see it, as the good sheriff, never for a moment ceasing his recitation, drops down in a squat and duckwalks across the office floor, a full-bore Chuck Berry, cameraman struggling to change headings, go with the flow.

Escalations are taking place. In what the sheriff is doing, the brutal comedy of it. In the ever-increasing alarm stamped on his face: wild eyes, frantic silent appeals stage left and right. In my anger, growing by the moment. In the anything-but-comedy of my horrible pride at the power of what I can do.

Again that half-moment delay, that temporal stutter. Eyes wide, face twisted in alarm, just as I picture him doing in my mind, the sheriff draws his sidearm.

In my mind he places the sidearm to his temple.

Onscreen he places the sidearm to his temple.

He pauses. The moment stretches. Stretches.

In my mind he stops talking.

Dervishness then, confusion everywhere, as deputies rush in to scoop the sheriff up and bear him away.

I reached out to turn off the TV with hands shaking. Didn’t sleep that night or for many nights to follow. Hardly left the apartment. Closed the door on what had happened, on what I could do, and have kept it shut, though every day when I turn the TV on, read the news, look around me at the mess of things, it gets harder. I answer the phone when calls come in, I go play my music, I come home. I keep my head down. I try real hard not to see things in my mind.

Mark Twain said a gentleman is someone who can play the banjo and doesn’t.

So far, I’ve stayed a gentleman.

FERRYMAN

Let me say this: I’d stopped dating, stopped looking, stopped even fantasizing that the sexy young woman with tattoos at the local 7-Eleven where I bought my beer was going to follow me home. Still felt a gnawing loneliness, though, one that never quite went away and drew me out again and again, till I had a regular round of watering holes, places that exist outside the official version, largely unseen even by those who live near, part of the invisible city. Clinica Dental, for instance.

On any given day there you look out windows to see saguaro that grow for seventy-five to a hundred years before the first arm comes along, and inside to see 99 percent Hispanic faces. Color and facial features ambiguous, Spanish serviceable as long as things stay simple, I don’t stand out. And I’m not there for free dental care, which makes it easier, I’m just there to be in the flow, to climb out of my own head and place in the world for a look around.

Airports, bus stations, parks – all are great for that. But county hospitals and free clinics may be the best.

After a while I began to feel that I wasn’t alone, that someone shared my folly. Like me, she blended in, but by the third or fourth glance, cracks started to show. Patients came and went – maids in uniform, yard workers, mothers with multiple kids in tow, an old guy that weighed all of eighty pounds lugging a string bass – and neither of us budged. From time to time, reading one of those self-help, motivational books with titles like Find Happy or Say Yes to Your Dream that turn out to be warmed-over common sense, she’d look up and smile. Now, of course, I understand book and visit for what they were: advanced research in how to pass.

When she left, I followed her on foot crosstown to Hava Java and lingered outside as she ordered. The place was busy, a jumble of young and old, hip and straight, some with lists of beverages to take back to the office, so she had a longish wait before staking out a table near the side window.

Two cups. Meeting someone, then.

But as I started to turn away, she beckoned, pointing to the second cup. I went in and sat. The kind of steel chair that looks great on paper but fits no part of the human body – legs too short, back at the wrong angle, seat guaranteed to find and grind bones. A young woman, evidently mute, went from table to table carrying a cardboard sign.

please help

homeless

spare change?

When my tablemate held out a ten-dollar bill, their eyes met for half a beat before the woman took it, bowed her head, and moved away.

‘Es café solo,’ my companion said, gesturing to the cup before me, ‘espero que esté bien.’

Given my skin color and where we just were, a fair assumption.

‘Perfect,’ I said.

Seamlessly she shifted to English. No taint of accent in her voice. She could easily have been from the Midwest, from Washington state, from California. I noted the lack of customary accoutrements. No purse or backpack, no tablet, no cell phone in its holster. Just the book and a wallet with, presumably, money and ID. I noted also how closely she observed everything: figures passing in the world outside, the low buzz escaped from earphones at a table close by, a couple leaning wordlessly in toward one another. Had I ever known someone so content to let silence have its place, someone uncompelled to fill every available space with sound?

Natalie was like that. Three or four weeks after we got together we’d planned a weekend trip to El Paso and she came out of the house that morning at six, smell of new citrus in the air, with a backpack you could get a small lunch and maybe a pair of underwear in.

‘That’s it?’ I said.

‘Like to stay light on my feet. You?’

My now-shamed suitcase was in the trunk.

Light eased itself gingerly above the horizon as we moved through Natalie’s battered neighborhood. The first three entrances onto I-10 were jammed. The city had grown too fast – a six-foot man on a child’s playhouse chair. Too many bodies shipping in from elsewhere, riding the wagons of their dreams westward, northward.

This was the girlfriend who told me I didn’t communicate, that I shut myself off from everyone and, when I shrugged, said, ‘See?’ But that was later.

Of the trip mostly what I remember is driving along the river one evening on our way to dinner and the best chile relleno I ever had, looking over at shanties clustered on the bluff above and thinking how could anyone possibly expect that these people wouldn’t try to cross over? Deliverance was right here, so easily visible, scant yards away. Reach out and you could touch it.

On that same trip, walking to breakfast the next morning, we found the bird’s nest. I turned to say something and Natalie wasn’t there. Two or three steps back, she was down on both knees.

‘It must have fallen out. From up there.’ She pointed to a palo verde. ‘There’s one broken egg shell.’

She was almost to the point of tears as she picked the nest up, ran a finger gently along it. Twigs, pieces of vine, what looked to be string or twine, silvery stuff, grass or leaves.

‘There’s something here with words on it.’ She held the nest close to her face. ‘Can’t make them out.’

Across the street stood a Chinese restaurant, alley running alongside, Dumpsters at the rear. I walked back for a better look at the nest. What she was seeing, intertwined among the twigs and other detritus, were slips from fortune cookies.

That’s also when I found out what Natalie read since, as it turned out, the backpack held more books than clothing. When she moved in not long after, she brought a sack of jeans and T-shirts, ten stackable plastic bookshelves, two dozen boxes of science fiction paperbacks, and little else. Kuttner, Sturgeon, Emshwiller, Heinlein, Delany, Russ, LeGuin. I’d begun picking up the books she forever left behind in the bathroom, on the kitchen table, splayed open on counters, in the fissure between our shoved-together twin beds. Many had been read and reread so many times that you had to hold in pages as you made your way through. Before I knew it, I was hooked.

The books were all she took when she moved out, that and her favorite photo, a panoramic shot of the Sonoran desert looking unearthly, lunar, forsakenly beautiful. Over the years I’d searched out copies of some of the books at Changing Hands and Bookmans. For the panorama I had only to drive a few miles outside the city bubble.

Not having been theretofore of an analytical turn of mind, nonetheless I came to recognize that, fulfilling as were these fantastic adventures in and of themselves, something far more substantial moved restless and reaching beneath the surface. The Creature swam in dark reverse of the woman in her white bathing suit above. Unsuspected worlds co-exist just out of frame and focus with our own. Transformations are a commonplace.

The same transformations occur in memory, I know, and what I now recall is the two of us standing there looking at the bare expanse together. Natalie’s photo of the Sonoran desert, or the closest I could find to it – but it’s her, my new brief companion, speaking.

‘It looks as though it doesn’t belong to this world.’

‘I often think that.’

‘Beautiful.’

‘Yes.’

She moved closer. Our arms touched. Her skin was cold.

‘Whatever lived there, on that world, its life would be spent in the pursuit of water. Certain plants would harbor water, water that could be harvested. When the blue moon came, always unpredictably, it would bring sudden, rapid rains. For an hour, two hours before they evaporated, shallow pools would form. And hundreds of life forms would race toward those pools, fill them, congest them. They would overflow.’

‘That’s quite a story – put together from almost nothing.’

‘Isn’t that how we understand the world we find ourselves in, by stitching together bits and pieces of what we see?’

As we had climbed stairs to the apartment she asked what I did for a living and I explained that I worked here at home, nothing of great interest really, pretty much the high-tech equivalent of filing, staring at computer screens all day. How living all the time in your head can make you strange. That getting out among others on a regular basis helped. We’d wandered toward the computer as we talked. The desert photo was my screen saver.

I’d drawn the blinds partly closed when we entered. Sunlight slipped through them at an angle and fell in a rectangle on the desk, looking like a second, brighter screen.

‘Eventually,’ she went on, ‘one species wins out in the race for water. For space and food. Drives the rest away or destroys them. But without them, without those others keeping the balance, that species can’t survive. It crosses over, into a new land. It changes.’

‘And as with all immigrants, now everything becomes about fitting in, being invisible.’

Quiet for a moment, she then said, ‘Becoming. Yes, exactly. It finds a way to go on.’

Later I will remember Apollinaire, my mother’s favorite poet: Their hearts are like doors, always doing business. I’ll remember what Garrett, a friend far more given to physicality than I, wrote in one of his stories, describing intercourse: We were bears pounding salmon on rocks. And I will remember her face above me in early dawn telling me I would never be alone again.

Then she died.

I remember…

Within minutes there’s a knock at the door. Dazed, I open it to find a man who looks exactly like her. There are others with him, a man and a woman who look the same. They come in, roll her body in bedspread and blanket Cleopatra-style, bear her away.

‘Thank you,’ one of them says as they leave.

That morning I go for a long walk along the canal. I take little note of the water’s slow crawl, of those who pass and pace me, of traffic on the interstate nearby, of the family of ducks who’ve made this their improbable home. I cannot say what I am feeling. Heartbreak. Shock. Pain. Loss. And at the same time…

Happiness, I suppose. Contentment.

Two weeks later I’m walking down the street on my way to coffee, peering up into trees for possible nests, when I hear the voice in my head. ‘Nice day,’ it says. ‘Maybe we could go for a walk along the canal later.’

I’ve come to a stop with the first words, looking around, wondering about this voice, what’s going on here – but of course I know. A father always knows. I was bringing a new life across.

FREEZER BURN

Within a week of thawing Daddy out, we knew something was wrong.

He claims, seems in fact fully to believe, that before going cold he was a freelance assassin; furthermore, that he must get back to work. ‘I was good at it,’ he tells us. ‘The best.’

When what he actually did was sell vacuum cleaners, mops and squeegee things at Cooper Housewares.

It doesn’t matter what you decide to be, he’s told us since we were kids, a doctor, car salesman, janitor, just be the best at what you do – one of a dozen or so endlessly recycled platitudes.

Dr. Paley said he’s seen this sort of thing before, as side effects from major trauma. That it’s probably temporary. We should be supportive, he told us, give it time. Research online uncovers article after article suggesting that such behavior in fact may be backwash from cryogenics and not uncommon at all, ‘long dreams’ inherent to the process itself.

So, in support as Dr. Paley counseled, we agreed to drive Daddy to a meeting with his new client. How he contacted that client, or was contacted by him, we had no idea, and Daddy refused (we understand, of course, he said) to violate client confidentiality or his own trade secrets.

The new client turned out to be not he but she. ‘You must be Paolo,’ she said, rising from a spotless porch glider and taking a step toward us as we came up the walk. Paolo is not Daddy’s name. The house was in what we hereabouts call Whomville, modestly small from out here, no doubt folded into the hillside and continuing below ground and six or eight times its apparent size. I heard the soft whir of a servicer inside, approaching the door.

‘Single malt, if I recall correctly. And for your friends?’

‘Matilda, let me introduce my son—’

Immediately I asked for the next waltz.

‘—and daughter,’ who, as ever in unfamiliar circumstances, at age twenty-eight, smiled with the simple beauty and innocence of a four-year-old.

‘And they are in the business as well?’

‘No, no. But kind enough to drive me here. Perhaps they might wait inside as we confer?’

‘Certainly. Gertrude will see to it,’ Gertrude being the soft-voiced server. It set down a tray with whiskey bottle and two crystal glasses, then turned and stood alongside the door to usher us in.

I have no knowledge of what was said out on that porch but afterwards, as we drove away, Daddy crackled with energy, insisting that we stop for what he called a trucker’s breakfast, then, as we remounted, announcing that a road trip loomed in our future. That very afternoon, in fact.

‘Road trip!’ Susanna’s excitement ducked us into the next lane – unoccupied, fortunately. She must have forgotten the last such outing, which left us stranded carless and moneyless in suburban badlands, limping home on the kindness of a stranger or two.

Back at the house we readied ourselves for the voyage. Took on cargo of energy bars, bottled water, extra clothing, blankets, good toilet paper, all-purpose paper towels, matches, extra gasoline, a folding shovel.

‘So I gotta know,’ Susanna said as we bumped and bottomed-out down a back road, at Daddy’s insistence, to the freeway. ‘Now you’re working for the likes of Oldmoney Matilda back there?’

‘Power to the people.’ That was me.

‘Eat the rich,’ she added.

‘Matilda is undercover. Deep. One of us.’

Susanna: ‘Of course.’

‘In this business, few things are as they appear.’

‘Like dead salesmen,’ I said.

‘My cover. And a good one.’

‘Which one? Dead, or salesman?’

‘Jesus,’ Susanna said and, as if on cue, to our right sprouted a one-room church. Outside it sat one of those rental LED digital signs complete with wheels and trailer hitch.

come in and help us hone

the sword of truth

Susanna was driving. Daddy looked over from the passenger seat and winked. ‘I like it.’

‘I give up. No scraps or remnants of sanity remain.’

‘Chill, Sis,’ I told her. ‘Be cool. It’s the journey, not the destination.’

‘To know where we are, we must know where we’re not.’

‘As merrily we roll along—’

‘Stitching up time—’

Then for a time, we all grew quiet. Past windshield and windows the road unrolled like recalls of memory: familiar as it passed beneath, empty of surprise or anticipation, a slow unfolding.

Until Daddy, looking in the rearview, asked how long that vehicle had been behind us.

‘Which one?’ Sis said. ‘The van?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, I’ve not been keeping count but that has to be maybe the twenty-third white van since we pulled out of the driveway.’

‘Of all the cards being dealt,’ Daddy said, ‘I had to wind up with you jokers. Not one but two smart asses.’

‘Strong genes,’ I said.

‘Some are born to greatness—’

‘—others get twisted to fit.’

‘Shoes too large.’

‘Shoes too small.’

‘Walk this way…’

Half a mile further along, the van fell back and took the exit to Logosland, the philosophy playground. Best idea for entertainment since someone built a replica of Noah’s Ark and went bankrupt the first year. Then again, there’s The Thing in Texas. Been around forever and still draws. Billboards for a hundred miles, you get there and there’s not much to see, proving yet again that anticipation’s, like, 90 percent of life.

‘They’ll be passing us on to another vehicle,’ Daddy said. ‘Keep an eye out.’

‘Copy that,’ Susanna said.

‘Ten-four.’

‘Wilco.’

Following Daddy’s directions, through fields with center-pivot irrigation rollers stretching to the horizon and town after town reminiscent of miniature golf courses, we pulled into Willford around four that afternoon. Bright white clouds clustered like fish eggs over the mountains as we came in from the west and descended into town, birthplace of Harry the Horn, whoever the hell that was, Pop. 16,082. Susanna and I took turns counting churches (eleven), filling stations (nine), and schools (three). Crisscross of business streets downtown, houses mostly single-story from fifty, sixty years back, ranch style, cookie-cutter suburban, modest professional, predominantly dark gray, off-white, shades of beige.

‘You guys hungry?’ Daddy said.

Billie’s Sunrise had five cars outside and twenty or more people inside, ranging from older guys who looked like they sprouted right there on the stools at the counter, to clusters of youngsters with fancy sneakers and an armory of handhelds. Ancient photographs curled on the walls. Each booth had a selector box for the jukebox that, our server with purple hair informed us, hadn’t worked forever.

We ordered bagels and coffee and, as we ate, Daddy told us about the time he went undercover in a bagel kitchen on New York’s Lower East Side. ‘As kettleman,’ he said. ‘Hundred boxes a night, sixty-four bagels to the box. Took some fancy smoke and mirrors, getting me into that union.’

Bagels date back at least four centuries, he said. Christians baked their bread, Polish Jews took to boiling theirs. The name’s probably from German’s beugel, for ring or bracelet. By the 1700s, given as gifts, sold on street corners by children, they’d become a staple, and traveled with immigrant Poles to the new land where in 1907 the first union got established. Three years later there were over seventy bakeries in the New York area, with Local #338 in strict control of what were essentially closed shops. Bakers and apprentices worked in teams of four, two making the rolls, one baking, the kettleman boiling.

‘So. Plenty more where that came from, all of it fascinating. Meanwhile, you two wait here, I’ll be back shortly.’ Daddy smiled at the server, who’d stepped up to fill our cups for the third time. ‘Miss Long will take care of you, I’m sure. And order whatever else you’d like, of course.’

Daddy was gone an hour and spare change. Miss Long attended us just as he said. Brought us sandwiches precut into quarters with glasses of milk, like we were little kids with our feet hanging off the seats. If she’d had the chance, she probably would have tucked us in for a nap. Luckily the café didn’t have cupcakes. Near the end, two cops came in and took seats at the counter – regulars, from how they were greeted. Their coffee’d scarcely been poured and the skinny one had his first forkful of pie on the way to his mouth when their radios went off. They were up and away in moments. As they reached their car, two police cruisers and a firetruck sailed past behind them, heading out of town, then an ambulance.

Moments later, sirens fading and flashers passing from sight outside, Daddy slid into the booth across from us. ‘Everybody good?’

‘That policeman didn’t get to eat his pie,’ Susanna said.

‘Duty calls. Has a way of doing that. More pie in his future, likely.’

Smiling, Miss Long brought Daddy fresh coffee in a new cup. He sat back in the booth and drank, looking content.

‘Nothing like a good day’s work. Nothing.’ He glanced over to where Miss Long was chatting with a customer at the counter. ‘Either of you have cash money?’

Susanna asked what he wanted and he said a twenty would do. Carried it over and gave it to Miss Long. Then he came back and stood by the booth. ‘Time to go home,’ he said. ‘I’ll be in the car.’

We paid the check and thanked Miss Long and when we got to the car Daddy was stretched out on the back seat, sound asleep.

‘What are we going to do?’ Susanna asked.

We talked about that all the way home.

BRIGHT SARASOTA WHERE THE CIRCUS LIES DYING

I remember how you used to stand at the window staring up at trees on the hill, watching the storm bend them, only a bit at first, then ever more deeply, standing there as though should you let up for a moment on your vigilance, great wounds would open in the world.

That was in Arkansas. We had storms to be proud of there, tornados, floods. All these seem to be missing where I am now – wherever this is I’ve been taken. Every day is the same here. We came by train, sorted onto rough-cut benches along each side of what once must have been freight or livestock cars, now recommissioned like the trains themselves, with eerily polite attendants to see to us.

It was all eerily civil, the knock at the door, papers offered with a flourish and a formal invocation of conscript, the docent full serious, the two Socials accompanying him wearing stunners at their belts, smiles on their faces. They came only to serve.

Altogether an exceedingly strange place, the one I find myself in. (That can be read metaphorically. Please don’t.) A desert of sorts, but unlike any I’ve encountered in films, books, or online. The sand is a pale blue, so light in weight that it drifts away on the wind if held in the hand and let go; tiny quartz crystals gleam everywhere within. At the eastern border of the compound, trees, again of a kind unknown, crowd land and sky. One cannot see through or around them.

They keep us busy here. With a failed economy back home and workers unable to make anything like a living wage, the government saw few options. What’s important, Mother, is that you not worry. The fundamental principles on which our nation was founded are still there, resting till needed; our institutions will save us. Meanwhile I am at work for the common good, I am being productive, I am contributing.