8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

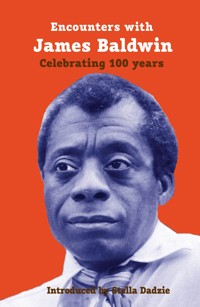

Celebrating the centenary of the birth of the trailblazing African American author, Encounters with James Baldwin is a wide-ranging volume of short essays, reflections, interviews and poetry. This moving collection demonstrates the significant legacy of the writer and activist who spoke truth to power during the era of the fight for Black civil liberties in the US, and after.

In this literary anthology, over 30 contributors reveal the influence of Baldwin’s thought, speech and writing to their personal journeys and their awareness of the need for social justice.

Stella Dadzie was born in 1952 in London, United Kingdom. She co-founded the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD), which worked relentlessly between 1978 and 1982 to challenge the predominantly white domination of the feminist and women’s liberation movements of that era. Additionally, her work extended beyond the written word into practical action, contributing to the enrichment of curriculums and development of anti-racist strategies in educational and youth services.

“… the words of this remarkable collection are breath blown back to our beloved ancestor James Baldwin, and he to them, to us: air we breathe, air we need, for these troubled times.”

— Kevin Powell – GRAMMY-nominated poet and activist

“From reflective pieces, interviews, essays, and poetic interventions, Encounters with James Baldwin confirms the enduring resonance of the life and work of James Baldwin across the globe. This is an important text for readers eager to consider the expansive legacy of arguably the most piercing and committed author and critic of the last century.”

— Rich Blint, writer and critic

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 287

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Stella Dadzie

Stella is a feminist writer, historian and education activist, best known for her co-authorship of Heart of the Race: Black Women’s Lives in Britain which was re-published by Verso in 2018 as a Feminist Classic. She is a founder member of Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD), a national umbrella group for Black women that emerged in the late 1970s as part of the British Civil Rights movement.

She has written numerous publications and resources aimed at promoting good practice with Black learners and other minorities, including resources to decolonise and diversify the UK national curriculum in schools and colleges.

Her most recent book, A Kick in the Belly: Women, Slavery and Resistance (Verso, 2020) centres women in the story of West Indian enslavement. She also wrote the foreword to Hairvolution: Her Hair, Her Story, Our History (Supernova Books) in 2021.

First published in the UK in 2024 by Supernova Books, an imprint of Aurora Metro Publications Ltd. 80 Hill Rise, Richmond, TW10 6UB [email protected]

X: @aurorametro F: facebook.com/AuroraMetroBooks

Encounters with James Baldwin: celebrating 100 years copyright © 2024 Aurora Metro Publications Ltd.

Introduction copyright © 2024 Stella Dadzie

‘Mea Culpa’ was first published in African Literature Today 40: African Literature Comes of Age, August 2022.

Cover image from photograph by Allan Warren, 1969, taken in Hyde Park, London © Wiki Creative Commons

Cover design: copyright © 2024 Aurora Metro Publications Ltd.

Editing & compilation: © 2024 Kadija George Sesay & Cheryl Robson

Individual contributors retain the copyright to their own works. All photographs are included either with permission, under creative commons licence or are in the public domain. If you have further information about the photographic rights contact [email protected]

All rights are strictly reserved. For rights enquiries please contact the publisher: [email protected]

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

This paperback is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBNs: 978-1-913641-41-2 (print) 978-1-913641-40-5 (ebook)

About the Co-editors

Kadija George Sesay is a Sierra Leonean/British scholar and activist. Her doctoral thesis on Black Publishers and Pan-Africanism will be published by Africa World Press. She is the Publications Manager for Inscribe/Peepal Tree Press, where she commissions anthologies, such as Glimpse, a Black British speculative fiction anthology. The first anthology she edited was Six Plays by Black and Asian Women Writers for Aurora Metro. Since then, she has edited several other anthologies and is publisher of SABLELitMag.

She has published her own poetry, short stories and essays. Her latest work is in New Daughters of Africa and her solo poetry collection is Irki; her forthcoming collection is The Modern Pan-Africanist’s Journey. She is founder of the first International Black Speculative Writing Festival, co-founder of Mboka Festival of Arts, Culture and Sport, and founder of the ‘AfriPoeTree’ app. She has judged several writing competitions and is the resident judge for the SI Leeds Literary Prize. She has received awards and fellowships for her work in the creative arts.

Cheryl Robson is the founder of award-winning independent publisher Aurora Metro, home to the popular culture imprint Supernova Books and the drama imprint Amber Lane Press. As publisher, Cheryl has been shortlisted for the ITV National Diversity Awards for both Lifetime Achievement and as an Entrepreneur. Aurora Metro has been shortlisted twice for the Independent Publisher Guild national awards for Diversity in Publishing.

Cheryl is also an award-winning playwright, editor and film-maker but is perhaps best-known for her successful campaign to commission and erect a bronze statue in honour of Virginia Woolf which was unveiled in Richmond in 2022 and has become a tourist attraction close to the publisher’s offices and bookshop, Books on the Rise.

Contents

Introduction by Stella Dadzie

Three Memories of Baldwin by Rashidah Ismaili AbuBakr

Blackspace by Victor Adebowale

Talking about Baldwin with Victor Adebowale

The World is White No Longer by Toyin Agbetu

Uncle Jimmy’s Calling by Rosanna Amaka

The Spirit of James Baldwin by Michelle Yaa Asantewa

Mea Culpa by Eugen Bacon

Meeting Jimmy Baldwin in Paris by Lindsay Barrett

Genius as Moral Courage by Gabriella Beckles-Raymond

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Phone Calls by Alan Bell

Never Make Peace with Mediocrity by Selina Brown

Searching for the Centennial Man by Michael Campbell

In a Photograph with James Baldwin by Fred D’Aguiar

Fires in Our Time by Thomas Glave

Can I get an Amen, Somebody? by Sonia Grant

What Kind of World is This? by Zita Holbourne

The Inspirational Blues by Paterson Joseph

Letter to My Daughter by Peter Kalu

James Baldwin Weeps with the Weight of Tiredness by Roy McFarlane

What’s Love Got to Do with It? by Ronnie McGrath

Revisiting James Baldwin by Michael McMillan

Six Degreesof James Baldwin by Tony Medina

Of James Baldwin and Futures Not Seen by Bill V. Mullen

The Fire is Now by Nducu wa Ngugi

If Sonny’s Blues… by Lola Oh

Fahrenheit 1492 by Ewaure X. Osayande

Passing by Nii Ayikwei Parkes

The Amen Corner by Anton Phillips

A Higher Calling by Ray Shell

For Jimmy by SuAndi

Wherefore, Nuncle? by Tade Thompson

Letter to My Brother by Patrick Vernon

James Baldwin and Black British Civil Rights by Tony Warner

About the Authors

“The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.”

– James Baldwin

James Baldwin, 1955. Photo: Carl Van Vechten

Library of Congress

Introduction

Stella Dadzie

“Love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.”

– James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

Despite the upheavals and injustices of the past century, mine was a blessed generation. As young Black people, encountering a world of entrenched racial injustice, our mentors included a veritable roll call of inspirational African Americans – Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr, Angela Davis, Maya Angelou, to name but a few – women and men who point-blank refused to accept a version of themselves that was anything less than equal to those who would have them believe otherwise.

Amongst those visionaries was James Baldwin – a diminutive man with a permanently crinkled brow and an infectious, gap-toothed smile – whose writings went beyond an indictment of racial oppression to confront issues of Black masculinity, sexuality, and homophobia. He made no attempt to hide his sexuality. In this respect, he was way ahead of his time. Long before terms like ‘intersectionality’ and ‘non-binary’ entered our common parlance, Baldwin recognised the complex ambiguities that define our sexual identity. His vision was of a world free of hatred, prejudice and division. His bequest to future generations was a fierce abhorrence of injustice and an equally fierce belief in the enduring power of love.

Born in Harlem, New York, in 1924, James Arthur Baldwin (né Jones) grew up in a home where his birth-father remained absent and unnamed. His mother, Emma, had joined the swelling ranks of Southern hopefuls who had fled north in a bid to escape poverty and segregation. The man she subsequently married, an embittered labourer and fiery Baptist preacher, was old enough to be her father. Like Baldwin’s paternal grandfather, he may well have been born into slavery.

James Baldwin’s relationship with his stepfather proved turbulent. Drawn to books and writing from an early age, he refused to accept the idea that his love of reading and films, and the fact that he had white school friends, was a road to damnation. With the encouragement of his mother and the support of teachers who recognised his early talent, Baldwin spent many hours in the public library on 135th Street, immersed in the novels of Dickens, Dostoyevsky, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. He wrote prolifically, almost as soon as he could hold a pen. By the time he entered his teens, he had already published a number of short stories and poems in his school magazine. He had also followed in his stepfather’s footsteps, becoming a youth minister in a local Pentecostal church at the age of fourteen.

As a young Black man growing up in Harlem in the 1940s, Baldwin encountered the harsh realities of racism on a daily basis, from casual discrimination and deferred aspirations to the poverty and violence of life in the ghetto. On leaving school, with his widowed mother and eight younger siblings to help support, college would become a distant dream. Instead, he worked in a variety of low-paid jobs whilst continuing to write.

Raised to believe that homosexuality was a carnal sin, it is no surprise that Baldwin struggled with his sexual orientation throughout his teens. Despite several relationships with women, he knew he was attracted to men. Moving from Harlem to the more liberal environment of Greenwich Village freed him from the constraints of his religious upbringing, empowering him to own his identity as a gay man. But as an aspiring writer and the grandson of an enslaved and vilified people, he had other identities to grapple with. He also longed to escape the restrictions imposed by his race and class.

In 1945, with help from the novelist Richard Wright, he won a fellowship, allowing him to devote more time to his writing. Soon, his essays and short stories began to appear in national publications. His decision to move to Paris three years later, thanks to another fellowship, proved life-changing. Away from the claustrophobic confines of post-war America, where segregation and racial hurdles intruded into every aspect of his existence, he was finally able to complete his first novel. As he later remarked, “once I found myself on the other side of the ocean, I could see where I came from very clearly.”1

The result was Go Tell It on the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical novel published in 1953, which explored the father-son relationship and the complexities of spiritual redemption. He saw the book as his way of confronting the issues that had caused him the most hurt, so he could move on to explore other themes. His second novel, Giovanni’s Room, published in 1956, was a bold attempt to do just that. Centred on the life of a white American man living in France who struggles with his homosexuality and tries without success to conceal it, it was dedicated to Baldwin’s former lover whom he had lived with in Switzerland, who had chosen, finally, to marry a woman. A story about pain, truth, regret and redemption, it was destined to become a classic gay text.

Baldwin was at his most eloquent when speaking out about race in America. In Notes of a Native Son, published in 1955, he explores the complexities of Black life through a pre-Civil Rights lens, commenting wryly on the casual racism African Americans encounter throughout their lives. No topic escapes his critical gaze – literature, the theatre, the Black press, the Black church, his relationship with his stepfather, his experiences of being denied entry to segregated venues, and his observations of what it meant to be a Black man living in post-war France. His insights resonate to this day. Seventy years ago, Baldwin was calling out colourism, stereotyping, anti-Semitism, tokenism, press sensationalism, church hypocrisy, racism in the military and the alienation of immigrants – issues that remain as relevant now as they ever were, as the contributions in this book will confirm.

A decade later, at the height of the struggle for Civil Rights, he resumed his critique in The Fire Next Time (1963), exploring the interface between racism, power and identity in two powerfully argued essays. The first, written as a letter to his nephew, urges future generations of young Black people not to let racism define who they are or what they can become. The second, delivered with the fiery eloquence of a sermon, addresses Americans in general, presenting an indictment of the country’s institutions, particularly the hypocrisy of the Black church, and calling for a new moral sensibility. As David McAlmont states in his review of Raoul Peck’s film about Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro, he was “a necessary fly in [America’s] illusionistic ointment.”2

Baldwin was expounding critical race theory before we even gave it a name. It is no coincidence that those who seek to stifle such debates in our contemporary moment have included this book on their list of banned texts in North American schools. Nor should it surprise us, in these dystopian, truth-twisting times, that the very arguments he used in his plea for racial harmony – a more honest assessment of history, for example, or an end to racial oppression – are blamed for promoting division and intolerance. As Ewuare X. Osayande puts so eloquently in his poem ‘Fahrenheit 1492’, the allies of white supremacy have “Elvis Presleyed history” and seek to “gaslight the whole world”.

Baldwin had returned to America in 1957, on the cusp of the Civil Rights movement. He threw himself into the fray, touring the Southern States, marching in Selma and on Washington, speaking at rallies and meetings both at home and abroad. Black communities were his primary audience. As Tony Warner recalls in his essay ‘James Baldwin and Black British Civil Rights’, despite his growing international stature, in 1985, he even gave a speech at a public library in Hackney. His friendships and acquaintances included men from across the Black liberation spectrum – Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr, Medgar Evers, Louis Farrakhan – but he was never anyone’s disciple.

His independent mind and eclectic range of interests were evidenced in a subsequent collection of essays, Nobody Knows my Name (1961) and in his third novel Another Country (1962). They move beyond issues of race and inter-racial relationships to explore themes such as bisexuality, domestic abuse, mental health, alienation and self-hatred. Human relationships in all their complexity were his muse, but race was always central to his discourse. As one biographer commented, “the whole racial situation, according to (this) novel, was basically a failure of love.”3

Baldwin continued to write about race throughout his life. In his play Blues for Mister Charlie (1964) he confronts his audience with the exoneration of those who murdered Emmett Till, a teenage boy who was lynched for speaking to a white woman. Paterson Joseph describes his experience of acting in the play in his essay ‘The Inspirational Blues’ as a moment of epiphany, allowing him and his generation “to feel their sense of belonging as a casual, obvious and observable, quantifiable, and undeniable truth.”

In Baldwin’s short story collection, Going to Meet the Man (1965) he dissects racism in all its guises. Yet race is always explored through the prism of love, human frailty and what would nowadays be called intersectionality – what Alan Bell refers to in ‘A Picture is Worth a Thousand Phone Calls’ as “the complexities of navigating multiple identities.” Queer themes loom large in Baldwin’s work, and several of his fictional characters are, like him, either gay or bisexual. Despite the homophobia he encountered, particularly from Black Nationalists, as with his views about race and religion, he was never prepared to be silenced.4

In later life, he went on to lecture at a number of American universities. He also wrote several more novels, including Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone (1968), If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) which Barry Jenkins made into an Oscar-winning movie in 2018, Just Above My Head (1979) and his unfinished memoir, Remembering This House, written that same year, in which he uses the murders of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers, all men he thought of as friends, to explore America’s contradictions, both past and present. As he continued to navigate the challenges of a white, male publishing world, Baldwin faced rejection from publishers, who claimed he was out of touch with contemporary America. He also faced growing rejection from some of his fellow Civil Rights activists, who deemed him to be too placatory. He was always a brilliant writer, determined to speak his truth and shame the devil (although not without a personal toll). And he was always a brutally honest thinker, who refused to jump on bandwagons simply because they rolled with the times.

Those grainy YouTube videos of Baldwin doing battle with the right-wing writer William F. Buckley at the Cambridge Union in 1965,5 or firing off his salvos on the Dick Cavett6 show in 1969, confirm that he was a wise, courageous, articulate man who had no qualms about speaking truth to power. He was also a mesmerising speaker whose oratory skills were honed in the pulpit at an early age. Sixty years on, listening to Baldwin speak is like listening to an inspired, eloquent preacher, only the focus of his sermon is a different kind of religion – a religion informed by his unwavering belief in his people’s rights to freedom and autonomy, expressed in a fervent prayer for the future of all humanity, Black or white, gay or straight. As Sonia Grant puts it in her essay, ‘Can I get an Amen, Somebody?’ his was a prophetic voice with no expiry date.

It should come as no surprise that Baldwin has had such a powerful and enduring legacy or that, nearly four decades after his death in France in 1987, he continues to influence our thinking in so many complex ways. Echoes of his voice can be heard in our poetry, our plays, our fiction, in our on-going narratives about race, class, gender and intersectionality. Sometimes we recognise the echo, sometimes we barely realise it’s there but, as Zita Holbourne demonstrates in her poem ‘What Kind of World is This?’, it is as pervasive as the sentiments he expounded. In his essay ‘Wherefore, Nuncle?’ Tade Thompson says Baldwin gave him “permission to disagree, permission to think, and permission to have my own rage.” SuAndi puts it another way in her essay ‘For Jimmy,’ crediting Baldwin with helping her to see the world she lives in “with different eyes.” For Nducu wa Ngugi, whose essay ‘The Fire is Now’ references Baldwin’s own essay ‘The Fire Next Time’, it’s about the fact that he challenges us “to understand this world and [our] participation in it.” Ronnie McGrath makes a similar observation in his essay, ‘What’s Love Got to do with it?’: “He […] allowed me to see the profound beauty of being Black,” he says, “and how to walk with my head held high in an often-hostile white world.”

Similar insights are made or implied by every contributor. In her essay ‘The Spirit of James Baldwin’, Michelle Yaa Asantewa embodies him as the Yoruba deity Baba Esu, pointing out that he “opens the way for self-awareness and critical self-evaluation by vociferously challenging us to examine our lives, our humanity, and our struggles to survive.” For Selina Brown, in her essay, ‘Never Make Peace with Mediocrity’ his words became a mantra, a constant reminder to refuse to settle for mediocrity, to “stand taller, to assert my worth, and to demand recognition for my capabilities.”

In his essay, ‘In a Photograph with James Baldwin’, Fred D’Aguiar, who met ‘Jimmy’ in the flesh several months before he died, describes him as a man whose broad smile “rented all the space on his head”, a man who “wrote as well as he talked”, exuding wit, humour and confidence. Yet, perhaps our beloved Jimmy simply had a good front. His writings suggest that, behind that contagious smile of his, he grappled with numerous demons, many of which haunt us to this day.

Today, poverty, hunger, the workings of imperialism in Palestine, the Congo, and many other global arenas, continue to engage us. Michael McMillan sums it up neatly in his essay, ‘Revisiting James Baldwin’. One of Baldwin’s most enduring legacies, he says, was that he taught him to eschew “a happy smiling-face version of history, as if the past has no relevance to our dark present.” We live in challenging times, with no room for the luxury of complacency. As Nii Ayikwei Parkes insists in his piece entitled ‘Passing’, “It’s time to pass from comfort to radical alertness. It’s Baldwin time.”

The fascinating range of essays and poems in this book testify to a mindset, a way of seeing and being and engaging with life, particularly if you are young and Black. They will resonate deeply with readers who hanker for a different, more compassionate world. They are proof, if any were needed, that Baldwin’s views have shaped and moulded the consciousness of generations of exiled Africans, not just in America but across the diaspora.

We stand on the shoulders of giants.

1 James Baldwin Reflects on ‘Go Tell It’ PBS Film, by Leslie Bennetts, New York Times, Jan 10th 1985.

2https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/david-mcalmont/to-james-baldwin-on-the-o_b_15508928.html

3James Baldwin: Artist on Fire, by W.J. Weatherby, New York: Dell, 1989.

4 see Eldridge Cleaver, Soul on Ice, in Ramparts, California, 1968 p.103.

5 Cambridge Union debate: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Tek9h3a5wQ

6 Dick Cavett interview 1969: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WWwOi17WHpE

“Trust life, and it will teach you, in joy and sorrow, all you need to know.”

– James Baldwin

Three Memories of Baldwin

Rashidah Ismaili AbuBakr

I was invited to Paule Marshall’s apartment on Central Park, West and 100th Street which was the first time I met James Baldwin. I went to a party there with a Trinidadian named Dr. Wilfred Cartey. He was a poet and a critic and wrote one of the first major critiques of modern African literature called Whispers of a Continent. I don’t even remember how we met, but Wilfred was one of those people who knew everybody, and everybody loved him. He was so charming, and everybody was just so amazed that he was so vibrant and alert and a ladies’ man. Yet he was blind – how could he do this? A lot of men were envious of him. He was drop-dead gorgeous. About 6’1”, or 6’2”, very slender, with this absolutely velvet skin. And very arrogant. Because he knew he was gorgeous. He never used any help like a dog or a cane because he always had gorgeous women with him, and his family worshipped him and treated him like a king. So, I had the honour of being with him that evening when we went to Paule Marshall’s apartment. Anyway, I had just read one of her books, Brown Girl,Brownstones, orSelena, so it was a big thing for me to go to her apartment. I hadn’t moved to Harlem then; I was still living downtown in the early 1970s.

So we went there, and there was all this food and all these people, probably only about ten people, but it felt like more … you know how when you have a party that really is jamming, it was like that, that kind of energy. And everybody was comfortable and talking about politics and the latest this and the latest that. Between 10 and 11pm, the bell rings, and this little guy comes in, and like it’s no big deal. Wilfred says, “Oh, hey, Jimmy.” And he just goes off again.

Then this forever and ever woman comes in. And it’s Miss Maya Angelou and she’s wearing heels. She’s about 6’3” in heels. And then there’s Baldwin, who had come up before her on the elevator and she’s cussing at him because he didn’t hold the “so-so” door for her. And who does he think he is? And everybody’s laughing. Oh, my, la-la-la. Before she walks in, she says, “Do you have my stuff?” And Paule runs to the bar and comes out with this bottle. Maya always preferred Johnny Walker. I don’t remember if it was Red Label or Black Label, but it was one of those two.

Once she knew you had it, she was okay. And the party began. Everybody knew each other except me. And I meet this man and he shakes my hand. He had the most incredible eyes. He and Amiri Baraka had these what I call owl eyes. Very big, slightly protrusive, but invasive in the sense that they just sort of went into you. They really “saw you.”

He looked at me and squeezed his eyes up and said, “How are you, my dear?”

Or something like that. Wilfred nudged me and I said, “I’m quite well, thank you. How are you?”

And he says, “Fair to middling.”

I never forgot that because I didn’t know that expression. And I thought, oh, I don’t know how to answer that, so I better not say anything. But Wilfred knew me well and he explained it, “Rashidah, that means sometimes up and sometimes down.”

I never forgot “fair to middling” after that. Then people started talking about literature and politics and the state of affairs. Freedomways1 was active at that point. Baldwin was very involved in it. So, they would talk about the articles. It was not just stimulating, it was a really, very deep discussion of everything in a way that made you feel like you had to know all these things, that all of these things were important. Then out of all of that came a novel or a painting or a dance or an article. These were not just fluffy conversations.

All of a sudden, Maya would burst into song, and she would sing a blues and she would dance and kick up her long legs. Sometimes she and Louise Meriwether would banter because one could cuss as well as the other. I was very intimidated by Louise, but Maya wasn’t intimidated by anybody. So that party was my first time meeting Baldwin.

His brother, David, bought a jazz club about two or three blocks away from where Paule lived. The spot was called ‘Cedars’ or ‘Cellars’ or something like that. And it was right off Amsterdam. Hugh Masekela used to play there. I mean, it was a really happening place.

Maya Angelou and James Baldwin had a very strong brother-sister relationship. They were like two naughty kids under the blanket talking about all of the adults in the room, snickering and laughing and poking fun. At the same time, they were very wise and insightful.

A lot of it was because of their experience. It could have been just the cultural difference between, say, growing up in Harlem or growing up in Arkansas where Maya was from. I was in my early twenties and in awe of everybody. Everyone seemed to be so sophisticated, intelligent, just always at the ready with a word or a phrase. So, I spent most of those times just looking and listening. And because they had long friendships, and they knew the people that they were talking about, they would make insider jokes about them and each other. They all had this kind of international worldliness about them that was alien to me.

Baldwin was a very caring person but he also had a mouth on him. He was not afraid to speak up. He was very bold and very unafraid to say anything. David, his brother, was almost always there to back him up. His fists were ready at the slightest hint of somebody disrespecting him; he was ready to pounce on them. So was Maya. They really were very protective of him. And then he would go away for long periods of time, I wouldn’t see him.

All of those people were around the same age. They were all between two and three years apart. Louise Meriwether, died recently, about six months after her 100th birthday. So that whole crowd has gone now; everyone who was in that room, has physically gone, but me.

*

Another memory that I wanted to share is not so nice. There was a big to-do at a conference of major African writers that included Baldwin, Achebe, Bebey,2 in 1980, in Gainesville, Florida. All the major writers were there. Baldwin was invited to speak as one of the keynote speakers. When he got to the microphone, it suddenly went dead. And then this voice comes over a loudspeaker and says, “Die, you f***ing, nigger, die... die... die.” It was loud. And then it went blank, and then the microphone came back on.

Baldwin being Baldwin, handled it gracefully but it was a very big embarrassment. Baldwin came from that conference to us, at the African Literature Association conference in Florida. You could tell he was angry, really angry. And he was really hurt. He said, “I want to talk about this moment. What does it mean? And how do we respond to that?” Everybody was very upset that he was treated in such a way. A lot of the critics, especially the white critics, were complaining that he was writing the same novel over and over and over again. And I remember him saying, “If I wrote the same novel over and over again, I’d still be able to write the same novel the next day, because the same old s*** happens every day.” That was his humour.

He was almost in tears. I think that’s one of my lasting images of him. He put himself out there. He put himself on the line to be a target and to show people how you go through that, how you work through that. But at the same time, he’s a human being. So how do you not be bowed, but have your personhood be respected? No one ever found out who did it or how it happened. No other problems happened before and no other problems after. He said, “That was a statement. It was not an accident.”

He was always very concerned about self-love. I think it pained him when people were deliberately mean and bullying. Those kinds of things really disturbed him and he understood what that means, to be a bully. He said the saddest thing was to be unlovable and he said that you feel unlovable because you don’t love yourself. You have to be able to love yourself and that most people who don’t love themselves can be very cruel to others.

Baldwin really loved people. He loved Black men. He loved Black women. He loved Black children. He loved Black adults, but he was very measured in his critique of people. He criticized the system, he criticized structures that oppressed and that kept people from realising their potential, but he didn’t criticize somebody just because he was white, he criticised people who thought that they could do what they did because they were white. That’s a very big difference. So, if you look at some of the comments that he makes about race, he talks a lot about love and being loving and being able to love. I think all that is quite philosophical. He was very Afrocentric in his thinking and his affiliation, I mean he was really, in his own way, a Pan-Africanist, too. He was a great writer and a great thinker, and a philosopher on love. Almost all of his work has a philosophical overtone to it.

*

This last memory I want to share is a much more pleasant one. My friend and I went to see Nina Simone at the Village Gate on Bleeker Street in the late 1970s or early 1980s.

There was a long queue with people saying she is ranting and raving, she’s crazy, la la la and that was because the timing in between the last show and the upcoming show for which we had tickets was beginning to blend into one. She was on stage, but she was refusing to perform, because she said she wanted her money. A lot of mostly white people were saying, “Why do we put up with her? Who does she think she is?” And we didn’t say anything. We went into the club, and it was full up to the rafters. When we finally got inside, the piano was on stage, but Nina was not. After maybe fifteen minutes or so she came out, everybody applauded, and she launched into what you could call a Nina Simone tirade. She was saying, “I am not a prima donna and it’s not true what people are saying, all these things about me. I just want to be paid for my work. I am a musician, you know, I practise, I come to the performance. I’m ready to perform but I want my money. And I want to be paid for my work.”

At first she was standing, and then finally she went and she sat at the piano. She started to play and then she stopped, and she said, “I’m not on the plantation anymore, I’m not your slave that you wind up and then I perform… I’m an artist.” She laughed. She was really complaining about the treatment that the Village Gate had shown her. Then people started whispering and I see this figure coming in… I hadn’t seen him for a very long time. But Baldwin, once you’ve seen him you can recognize him anywhere. So, I said to my friend, that looks like Jimmy Baldwin. He was going to take his seat and Nina Simone saw him and her whole body just changed… she almost jumped up. “Aha! There’s my brother James Baldwin, now f*** with me if you want!” Everybody was clapping, somebody said something, so he went up and sat next to her at the piano and you could imagine him saying something like, “Nina, what are you doing?” and he was trying to calm her down. He said, “You’re a musician… just be a musician and do your job.”

She said, “You stay right here,” and he said something like, “You’re testifying,” or something like that. “Let’s go to church.” So, she started to play this song, “Take me to the water...” just some very simple chords and then Baldwin was singing with her. There were a lot of Black people in the audience and some of them knew the song and joined in.