Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Beneath the wide skies of Orkney Linda Gask recalls her career as a consultant psychiatrist and her lifelong struggle with her own mental health. After the favelas of Brazil, the glittering cities of the Middle East, and the forests of Haida Gwaii, will she find perspective, spiritual relief, and healing in her new home? Her troubled past is never far away.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 339

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

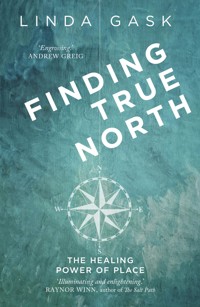

Praise for Finding True North

‘Finding True North reminds me why I would rather consult a physician who at times struggles herself, rather than one who has remained above the fray, and how helpful it is to find the right place. In this case, Orkney. This is a story of struggling adults who find that True North is a place in oneself that is sustained by love and loyalty. We need a right place, and in the end we find and sustain True North in and for ourselves.’

Andrew Greig, author of

At the Loch of the Green Corrie

‘An illuminating and enlightening book, beautifully illustrating the importance of place on our mental and physical wellbeing.’

Raynor Wynn, author of The Salt Path

‘A quietly moving account of living with long-term depression that weaves together Linda’s experiences as a doctor and a patient. With contemporary lifestyles that seem to be ever on the move, this book is a timely reminder of the stabilising effects of attachment to place.’

Sue Stuart-Smith, author of

The WellGardened Mind

‘Linda Gask’s writing and wisdom about depression are like no one else’s and I turn to it time and time again to feel the comforting chime of shared experience.’

James Withey, author of The RecoveryLetters

‘Linda Gask is an experienced clinical and academic psychiatrist. She also suffers from depression and loves the Orkneys. It would need a master storyteller to weave these themes together into an intriguing, poignant and highly readable narrative. Fortunately, that is exactly what she is.’

Sir Simon Wessely, Regius Professor of Psychiatry,

King’s College London

‘This is recovery not as a political stick with which to beat the disenfranchised, but self-help and self-care that is truly transformative.’

Andre Tomlin, Mental Elf

‘Finding True North is beautifully written, in language that powerfully evokes not only the healing environments Linda has discovered in her quest. This is a memoir, but quite exceptional as Linda Gask brings not only her experience as a patient but also her knowledge, experience, and academic credibility as a leading psychiatrist. In no way sugar coated, it describes the struggles she has experienced in gritty detail but nevertheless offers hope. It is powerful and moving and quite exceptional.’

Kate Lovett, Dean of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

‘Deceptively easy to read given the deeper meanings being exposed, each new paragraph draws you on.’

Prof Tony Kendrick MD FRCGP FRCPsych (hon) FHEA, Professor of Primary Care, Primary Care & Population Sciences

‘I really enjoyed reading Finding True North, especially the sensitive, thoughtful and informed discussion about the meaning of “Recovery”.’

Professor Wendy Burn,

President, Royal Society of Psychiatrists.

‘Part novel, part journey of self-discovery and identity, this book offers the reader new insights into the most common mental illness, depression, reaching far beyond the academic aspects or, indeed, the usual “self-help” advice offered in many publications.’

Clare Gerada, Co-Chair NHS Assembly,

Previous Past Chair of RCGP Council

Member of BMA, RCGP and GPC Council

Linda Gask trained in Medicine in Edinburgh and is Emerita Professor of Primary Care Psychiatry at the University of Manchester. Having worked as a consultant psychiatrist for many years she is now retired and lives on Orkney. She maintains a popular mental health blog, Patching the Soul (lindagask.com), and contributes to Twitter as a mental health influencer. She is the author of The Other Side of Silence (2015), which was featured on BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour and serialised in the TimesMagazine. In 2017 she was awarded the prestigious President’s Medal by the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Also by Linda Gask

The Other Side of Silence

In memory of Maureen Johnston

– who welcomed me.

First published in Great Britain in 2021

Sandstone Press Ltd

Suite 1, Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright 2021 © Linda Gask

Editor: Robert Davidson

The moral right of Linda Gask to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-913207-34-2

ISBNe: 978-1-913207-35-9

Cover design by Stuart Brill

Ebook compilation by Iolaire, Newtonmore

Contents

A healthier life

Other people

Work

Escape

Being kinder to myself

In sickness and in health

True North

Happy to feel sad

Meaning and Hope

The problem with forgiveness

Healing

Acknowledgements

Select bibliography

CHAPTER 1

A healthier life

I was eighteen when I first came to Orkney, the island archipelago that lies beyond the North coast of mainland Scotland. Finished with school, I set off to explore alone, to discover these far-flung islands. When I came up from the saloon of the old St Ola, onto which cars had to be winched one by one, to gaze upon the famous towering sea stack, I was overwhelmed by the sheer scale of huge red sandstone cliffs to which it had once been attached. Known as The Old Man of Hoy, this vertical stack of rock seemed to beckon me towards the islands. Yet it was thirty years before I returned.

I’ve clambered through caves formed by hot springs in the heart of a glacier in the short summer of Iceland. Stared out to the ice floes of the grey-blue Baltic on the coast of Denmark. Whiled away the days on an agate strewn shore in North West Canada with the mountains of Alaska floating above the horizon. Walked on crisp snow in Arkangelsk in the middle of winter when the sun barely rises before it sets. For decades I was bewitched by the lonely beaches of the Western Isles of Scotland and held them in my mind as my spiritual place of retreat, an image of solace to call upon when times were hard. Yet I could never make a lasting home there. They would never be a place to which I would truly belong. I would always be a half Scots, but English speaking, outsider. Whether it was with the passage of time or a dawning realisation of the meaning of things, I finally acknowledged the need to return to Orkney. I have come here many times in the last decade to think, to write and, most of all, try to make sense of things. I now need to know if Orkney will be the place where I can patch up my life.

This morning I should be at my desk in the corner of the kitchen, by the front window of the house, but I am easily distracted. The fire in the stove has gone out. Beside the hearth is an Orkney chair with handwoven straw back, where I sit to read in the evening. A tall and narrow bookcase that holds what I’m currently working on is crammed into the corner next to the walnut writing desk that came with me from Yorkshire. A brass lamp lights the desk morning and evening; in the afternoon if there is sunshine my workplace is well-lit from the west. My pens and pencils are collected in an old mug decorated with the cover from Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’. Of all the pots and pans packed to bring to Orkney, its handle was the only thing that the removal men broke in transit - hopefully it wasn’t symbolic. Beyond the desk the latticed window, deeply recessed into the double layered stone walls of the old house, looks out onto a lawn and one rather stunted tree, surrounded by a patch of dense green wilderness that separates my land from the fields beyond. There are only a few houses scattered in the distance and no immediate neighbours other than wildlife.

One of those people who love nature but has forgotten the names of the animals and plants around them, I’ve been discovering my wild Orcadian garden. Some of the flowers are familiar from childhood: once carefully pressed between the pages of an exercise book for school. There’s rather too much yarrow and rosebay willow herb, but in spring there are snowdrops, golden yellow crocuses, daffodils and a patch of bluebells nestled beneath the willow. Summer is a riot of wild pink roses as the rhubarb – ubiquitous in Orkney – begins to sprout, tart wild gooseberries appear and the clumps of montbretia by my desk window turn fiery orange. Then autumn arrives with a crop of berries from the tangle of brambles, the roses shed their petals and only bright red rose hips remain.

‘There’s a proper flower border somewhere under there,’ Bob, who cuts the grass, told me last year.

‘I’m not sure if I want you to hack it all back,’ I replied. However, the rose bush has spread so much I feel like the sleeping beauty hidden from the world behind a forest of thorns.

It’s a curiously still day, which means the squadron of flies which patrols the back of the house, in the lee of the breeze, will be out in force. It has been raining in the night and the flagstones are still wet. The sky is grey, but across the valley, behind the low hills I can see the purple mass of Hoy catching the sunlight from the East as it emerges from mist. The air is fresh and sweet, with only a hint of the farmyard smells of a couple of days ago, when my neighbour over the way decided to start muck-spreading. I made the mistake of hanging out my bed linen on the line, only to have to launder it again. Daffodils are coming out, and yesterday I saw new-born lambs in the field up the road. A blackbird is hopping about on the lawn and there are sparrows perched in the tree, possibly contemplating where in the eaves of my house to build their home this year.

I haven’t spotted any hares in the last week.

‘When you’ve been here a while, you’ll start to see them everywhere,’ my friend at the neighbouring farm told me the other day, but I haven’t reached that point yet.

Last autumn, when the weather suddenly turned foul and a storm swept in from the Atlantic, I spied a young hare sheltering outside the back kitchen window, behind the house, crouched low with its long black-tipped ears resting on its back. I’d never been so close to a wild living thing, even if there was a double-glazed pane of glass between us. Every time I went to boil the kettle to make a mug of tea I said ‘hello’. The hare trembled slightly as the wind ruffled her coat but studiously avoided eye contact. I’m sure she knew I was there. Rain and wind battered the house for three days, rattling the roof tiles and waking me in the middle of the night as it clanged the letterbox like an impatient visitor. When it eased off on the third morning the hare stood on all four legs, shook herself, lolloped gingerly to the corner of the garden and, a few moments later, was gone. I missed her company.

A psychiatrist, which is what I was for more than thirty years, is a medical doctor specializing in mental health conditions. I’ve helped many people to recover. I’m a Professor, an expert in my field, who has written numerous books and papers about mental health. However, all that knowledge has not made me any better at managing my own. That is still something I struggle with daily. Indeed, in my experience, the one question that health professionals rarely ask, but really ought to, must be: ‘How do you get through the day?’

Those of us, like me, who are troubled by life problems and unresolved psychological conflicts have to find our own ways of living with our emotions. Many of us have ‘residual’ symptoms of depression and anxiety which wax and wane from when we get out of bed in the morning through hours of being, doing, feeling and interacting before getting back under the duvet. Surviving this daily experience is central to the process of recovery. I’m still working on the task of getting through the day on my own and adopting a healthier lifestyle.

Soon after I retired from work, three years ago, I set about finding a home here. I say ‘I’ even though I am married and have been for more than twenty years, but my husband John was still committed to a life in the South. There was a period after I finished working full time when I wasn’t sure if I wouldn’t be living here alone most of the time. We were staying together on holiday, only a mile away, when this cottage came up for sale. Described as a low white rendered cottage in the solicitor’s particulars, it was situated in a shallow valley in the centre of the largest island of the Orkney archipelago, confusingly called the Mainland. It had an uneven flagstone path along the front and side and a lawn which looked as if it had been only recently fenced off from the neighbouring field.

It’s not a traditional cottage. If it wasn’t sturdily built the wind that blows from the west straight into the front door and my ‘study’ window would demolish it. My nearest neighbour lives in a new house with a windmill two fields away, and at each of the points of the compass there are tumbled collections of farm buildings to be seen in the distance. My friend lives at one of these, a quarter of a mile down the road. In the summer, her cows in the next field cluster around the fence with their calves, watching in fascination as I hang the washing on the line. In winter their bellows echo around the valley. There are few trees in Orkney and a scrub of willow is my only shield from the west wind. Cutting it back for the view may have been a mistake, but it was worth it to catch sight of the purple grey mass that is Hoy, the only really mountainous place on Orkney. If I cannot see water, I must be able to see a hill.

The house was built around the end of the nineteenth century as a but-and-ben, a simple Scots two room cottage, and was probably a farm hand’s home as it stands on a plot at the corner of a field. Each generation of residents has extended it: a kitchen at the back, a loft room, and finally a wonderful airy lounge where the byre was once attached to a side wall. It was this room with its two front facing windows, a door opening directly into the garden and skylights through which huge shafts of sunlight split the soft warm air, that seduced me into buying. It took me almost a year to make it habitable, travelling up and down from Yorkshire.

Our basic physiological requirements are air, water, food, then clothing and shelter to protect from the elements: essential even for hares. It was winter when I took possession of the empty cottage, so I decided to fly from Manchester, limiting what I would carry. The first thing to arrive, a few hours after me, was a bed previously ordered from the local furniture shop. What I hadn’t expected was for it to require ‘self-assembly’.

‘Is it OK for us to be off now?’ the two young delivery men asked when they carried the last part of it into the empty bedroom.

‘Yes, that’s fine, thanks.’ Too proud (and embarrassed) to admit to lacking practical skills I rushed off and purchased a screwdriver, as well as a kettle, tea and milk. Before the evening was out, I had at least warmed myself through and built somewhere to sleep, although there had been a few puzzling pieces left over that didn’t seem to fit anywhere. The only effective heat was from an ancient coal stove in what had been the lounge, so that first winter was still Baltic despite the fire. I had to wrap myself in a duvet, night and day, as I used to when I was a student in freezing digs in Edinburgh. It did begin to feel as though I was trying to recreate my youth – but not in a good way – and I wondered if the whole proposition had been a mistake. The previous owners had decided they would prefer to live in Spain than Orkney, a decision I soon understoond rather too well. My budget extended to fixing the heating, the kitchen and the bathroom, but getting the house waterproofed was more challenging. Facing west it gets the full blast of the horizontal rain that Scotland is famed for, the combination of gale force wind and water. Woken by a storm one night I stepped barefoot into a huge puddle of water that had been forced around the edges of the glass panes in the newly fitted front door.

‘A porch – that’s what you need,’ the joiner told me.

‘But won’t the water simply soak the porch then?’ I asked.

He shrugged. There’s a price for living here.

Keeping my mind on track is essential as I am alone most of the time. It’s a great place to practise the skills of allowing the boxes labelled ‘difficult thoughts’ to pass along the conveyor belt of my mind without having to unpack and ruminate over them. If I allow a worry to take over my mind here, it’s quite difficult to elude it. My mood soon begins to spiral downwards.

Everyone’s experience of what we call depression is different. For me, mood is paramount. Working and rushing around, I was probably less aware of it, yet my mood is a key part of my ‘being in the world’. It’s the lens through which I see what is happening around me, and its qualities colour, clarify or distort the ways I think about myself, the world and the future, much as the Hall of Mirrors in the seaside fairground where my father worked, warped reflections. Sometimes I was amused by the reflection; other times it horrified me. I’ve come to see that ‘mood’ is what must be managed if I am to reclaim my life.

The Surprise summit in the Peak District near my southern home is well-named as it rewards you with an unexpected panoramic view of the valley and peaks beyond. The crest of Howe Road near Stromness in Orkney usually has a similar impact because of the sudden realisation, as you top the hill, of a perfect composition. Here before you is the settlement nestled around the bay, framed by sea and hills, with the Hamnavoe ferry, when in dock, as its focal point. When John was in Orkney to celebrate his birthday a little over a year ago, that picture postcard view held no joy for me. As we drove down towards the harbour, the snow-capped island of Hoy rose from the sea to the west with the small island of Graemsay in front, with its two tiny white lighthouses which must be aligned by the captain of a ship to find the safe channel. It was a typically Scottish winter day, of the kind that reminds you how many different shades of grey there are between black and white. Sunlight tried to squeeze between the clouds with little success and the scarce winter daylight in Orkney echoed the approaching darkness inside me. I should have been relaxed, yet I wasn’t. Everything positive about the day was ruthlessly filtered out by my mood. On the outside I could just about hold a smile, but inside I was barely holding myself together. The problem is that when I’m going down, I don’t recognise it until quite late. Others see it first.

John put it succinctly. ‘When you aren’t well you start to talk all the time, and about 80 per cent of it is rubbish . . . and you’re doing that now.’

‘I’m not, am I?’

‘Yes, you are.’

What he was referring to is the emotional and verbal expression of anxiety, the constant seeking of reassurance and rumination on life’s problems; the wringing out of my brain rather than my hands, in a way that drives those around me crazy. I’ve tried to learn my ‘early warning signs’ and the most obvious is the pain when my gut twists. I wander around drinking tea to distract myself and, in the past, have sent emails in the early hours only to regret them the following day.

John was right, I was becoming unwell again. The terrible feeling that there was a weight bearing down on my chest had returned, and I was exhausted and weary with the world. I stopped caring about my appearance and instead focused on the anguish and torment of what others couldn’t see: feelings of guilt and despair and a terrible sensation of being beyond feeling, that the joy had gone out of being alive and there was no point to anything. The world had subtly changed from a place with potential for happiness to one I saw only in monochrome colours, one that seemed empty, hopeless or even dead, and attempts to change were doomed to fail.

There is a moment I recall from years ago when we first moved to Yorkshire. From the brow of the hill we saw the parish church in its centuries old position. If I had been of a mind to, I could have seen that the sky was blue with fluffy white clouds gliding past in the breeze and that the river Don was sparkling in the winter sun as it rushed towards Sheffield. Yet what I focused on that day was the dirty brown discoloration of the water at it washed over discarded beer cans, and the stench of the pollution from traffic as it poured through the village at the end of the pass. Thoughts rushed through my mind so quickly it was hard to grasp one for a closer look. A familiar sense that something terrible was going to happen and nothing could prevent it overwhelmed me. The professional side of my brain, watching from the sidelines, calls this Generalised Anxiety. The evil controller of my mind who is always there, waits to press the buttons marked ‘churning of the stomach’, ‘trembling hands’, or ‘nameless fear’. The beauty all around me passed by and all I noticed were the blemishes.

A few days later we walked the same route, stopping for a moment to watch the river, and the world looked quite different. ‘The level is lower than it was the other day and look! Spring is really here,’ I pointed to an expanse of delicate white buds, a bed of snowdrops on the bank ahead of us, ‘and the daffodils are coming up in the front garden too.’ The rubbish and pollution were still there but were much less important. I was feeling positive about the world again.

‘You didn’t notice any of it the other day.’ John sounded relieved. ‘Before, you were preoccupied with how dreadful it was.’

The problems were still there but had receded into the background as they always do.

Mood is more than simply ‘feelings’ or ‘emotion’. It’s a longer lasting state of mind that encompasses all thinking. It can transform how events are viewed and change yesterday’s great opportunity into tomorrow’s disaster in the making. We aren’t always aware of our mood but the people around us often are.

My boss for many years, a professor in the university, had a notoriously changeable mood. ‘Be careful what you ask him about today,’ his secretary, would warn me when I waited in silence outside his office, ‘He’s really grumpy.’

As I entered the room, he would, at best, greet me with an air of irritation, telling me with a grimace, ‘Whatever you want, I doubt I can help you.’ Other times it might be, ‘Go away and come back when you’ve something useful to say.’

But then another day the atmosphere would be quite different, and everyone would know. The secretaries in the outer office would be chatting away, basking in the glow of good humour emanating from within. He would put his head around the door and call, ‘Come in, come in, what can I do for you? Sit down and tell me all about it.’

Mood is not only the spectacles we wear but the overcoat we show to the outside world. Our mood is both us and yet not us. I cannot manage without my glasses although I know, rationally, that if I could will myself to change them the world wouldn’t look as bad. Tomorrow, things may appear differently through them: brighter, sparkling and full of hope. When we’re feeling positive, even the most boring things can seem worth doing. Mood balances on a knife edge and can change within the space of a few hours, but then it can remain stable for months.

Another problem for me is the ‘timekeeper’ with his stopwatch sitting somewhere in my head, usually insisting on what should be achieved each hour of the day. This is something I often observed in my patients. I don’t set myself a raft of impossible goals on paper any more, although I have done. Revising for my final examinations at university, my obsessional planning got out of control to such an extent that I spent more time revising the plan than the knowledge. That timekeeper still measures out my day, and if I don’t start something at the beginning of an hour, it can be difficult to start until another hour is up. I get stuck. I’ve lived with this problem all my life, and I know I’m not alone in this, but now I’m more aware. The danger is in counting away the hours of our lives.

Writing here, now, lifting my head every so often to watch the clouds scud across the sky outside my window, my mood is bright. It’s much easier to be alone now than when I have been severely depressed. Last year, during a very low ebb, there was a period when I would spend hours waiting to get out of bed, only to feel so exhausted that nothing meaningful or productive was possible. Even reading a book was beyond me. To simply keep going, and not give up hope, I make myself set a few simple goals to maintain a daily routine: getting out of bed, washing, eating, eventually venturing outside for a walk.

‘I feel so guilty about you taking care of me all the time when you have enough to cope with already,’ I would say to John, trying not to blame myself and descend further into a spiral of guilt.

My psychiatrist thinks, because it is clearly stated at the top of every letter he writes to my GP, who sends me a copy, that I have a recurrent depressive illness. Almost every word of that last sentence is contested.

Everyone has opinions on mental health and illness: ‘experts’ who have studied it; people who have experienced it and are called ‘experts by experience’; those who have never suffered from it or know anyone who has, yet still have strong views. They all seem to know what you should do to ‘get better’ and ‘recover’, which generally means returning to your ‘old’ self. Many do, though some, like me, have persisting symptoms or relapse from time to time.

They wouldn’t dream of offering advice to a heart attack survivor or someone with a broken leg. They don’t understand that what they call ‘depression’ may only be the unhappy feelings they can usually shake off. So . . . you can do that too. Yes?

This year I intended to get into a healthy daily routine here in Orkney, but don’t get the idea that I am a virtuous paragon of self-care. I’m far from it. There is so much information about the kind of lifestyle I should lead but keeping it up gets harder and harder. It has to become a way of living, different from doing something for a limited period in the knowledge that your mood will improve. The fact is that I am going to have to change my lifestyle to reduce the risk of another relapse.

Yesterday I was good.

I got out of bed before 8.00 a.m., took my tablets for mood, blood pressure and thyroid, and ate a healthy breakfast. Ten minutes on the rowing machine in the attic and fifteen meditating (there is no point trying this any earlier as I find the sound of my breathing curiously soporific), left me with enough enthusiasm to do a few household chores and write for a couple of hours. After a lunch of soup and fruit I drove to Stromness for the shopping and walked to a seat overlooking the harbour, my favourite place in town. It bears a dedication to George Mackay Brown, who lived and worked in Stromness for his entire life, and who experienced long periods of depression. His former home is nearby, an unassuming council maisonette. Drawing on the inspiration of this place, the harbour with the hill called Brinkie’s Brae rising behind, he created some of Scotland’s finest poetry and prose, all rooted in the culture of Orkney.

With such a wide view I can see everything that is going on in my world. Weather permitting, I sit watching fishing boats come and go on the sapphire water: a person ‘wild swimming’ offshore; the Hamnavoe appearing from the west side of Hoy gradually growing in size as it comes into Scapa Flow, the great natural harbour between the islands. It’s a roll-on roll-off these days, huge in comparison to the old St Ola. I would have gone for a longer walk but couldn’t find the energy.

Back at home, I did some more writing and ate a fishy salad with lashings of olive oil, the closest you can get to good mood food in the north of Scotland. I drank no alcohol.

John and I talk on Skype most nights. I told him about my progress. ‘I’m pleased you’re getting exercise,’ he said, ‘but you could probably do with more than that.’

‘So how did you spend your day?’ I asked. He was in Yorkshire at the time.

‘I walked up the hill behind the house this afternoon, then into the village and back. I spent half an hour on the exercise bike later.’

‘Very good, that will help your blood pressure.’

‘Tomorrow I’ve got to go over to Mum’s for a couple of days.’ His voice tailed off as energy drained out of him. I knew this visit would not be good for his blood pressure.

John looks after his mother who is suffering from dementia, caring for her not quite full-time but about half of the days of each interminable week and sometimes more. When I am back in Yorkshire, he is either at her house, exhausted on his return, or anxious and despairing about going back. John’s elderly parents were the reasons we have stayed in Yorkshire for so long. His father died a few years ago, and his mother is alone.

‘How can I help?’ I have asked him so many times. ‘How can I make it easier for you?’

‘Stay well and take care of yourself properly,’ he always replies.

She is in her late eighties, widowed but determined to stay in her own home and that her children will take care of her there. Since John was made redundant from his job as an accountant last year, and for a long period before, while he was coping with a demanding job, this has been his life and ours. He will not let me share the physical burden, but I try to help with the emotional one.

‘Never mind,’ he said. ‘It won’t be long before we’re together and then we can do some walking.’

Inside I silently groaned. It is always wonderful to have him here for a break, but he is so much fitter than I am. I find myself stifling something that might be frustration or even anger as I trail behind him. His stride is longer than mine, so he always ends up two steps ahead of his ‘dutiful’ wife.

There are advantages to living alone. I don’t always have to behave well.

Indeed, why do I have to be good at all? I find it impossible to be good all the time. Can anyone truthfully manage that? Getting out of bed with a surfeit of energy and a full reservoir of self-control, I might keep it going for a few days but no longer.

Trying to lose weight, each day of the last week I have avoided cake, but today I gave in to a heavenly slice of apple tart with a scoop of ice-cream. Late out of bed, I couldn’t be bothered with my morning exercises and got distracted by Twitter. I cannot keep up good behaviour indefinitely and then begins a vicious cycle because it is even harder to get going next day.

Western culture sets great store by self-discipline as a way of managing our fears, emotions and behaviour at home and in the workplace. If we cannot ‘pull ourselves together’ we must be weak. Trying to control ourselves we can make matters worse and undue attention to self-discipline can generate even more problems: have you ever tried to will yourself into sleep? Over-controlling becomes the problem even if the surprising thing is that self-control works as well as it does. Sometimes we can exercise it but at other times it’s impossible. The pounds have disappeared in the past when I’ve been depressed, but when well, or taking certain pills, it takes a Herculean effort to lose them.

‘I’ve been diagnosed with diabetes now on top of everything else,’ I remember one of my patients, David, telling me. He had been feeling suicidal after a series of failed relationships but was just able now to cope with everyday life. In his youth he had been a professional sportsman – very fit and healthy.

‘I know you have gained quite a lot of weight . . . I’m afraid it’s probably the medication . . . ’

‘And the cream cakes,’ he laughed, ‘I can’t seem to resist them . . . but I don’t want to risk changing anything. I’m so much better than I was before.’

I wondered if he was just trying to please me, not only by telling me he was recovering on the pills I was prescribing, but also by not blaming them for his gain in weight – even though they were undoubtedly contributing. ‘Everything you are on will be increasing your appetite.’

At that time, I too was struggling with a similar problem, only for me it was caused by craving sugary drinks to quench thirst – a side effect of the lithium that my own psychiatrist had started me on.

However, one of the pills David was taking, I now know, is very likely to cause major weight gain, which can trigger diabetes. Ironically the makers organised a lunchtime lecture for the medical staff at our hospital on the topic of ‘managing diabetes’, accompanied by a generous Indian banquet. ‘Take as much food away as you want,’ the drug representative called after us as we left the room. ‘There’s plenty left.’

‘So much for our own health,’ my colleague muttered as he filled a second container, then paused to explain, ‘This is for my wife.’

Everyone departed laden with boxes of delicious curry. Pharmaceutical companies traditionally seduce doctors with a free lunch.

For those of us who are patients, it sometimes feels as if the only way you can please your doctors, and everyone else (and be seen to be ‘good’) is to demonstrate how hard you are working at getting well: taking the prescribed medication, exercising self-control, getting back to your ‘old self’. Your duty is to those who care for you and rely on you. The need to discipline your mind and body can become the most significant thing in life. Yet there is more to praise about a person than weight, blood results and compliance with the medication.

Still a rebellious child inside, if left to my own devices I would eat only bread, cheese, red fruits (and cake!) and drink plenty of orange juice and tea. I lived on that for almost year with the occasional meal out, and I was fine – really. And I so dislike going to bed. Without John to get me there I would sit lost in my thoughts, reading, tweeting, surfing the net or watching the TV for hours. Once in bed I can’t get up and I can lie in bed half the morning like a teenager. When I was nine years old my mother took me along to the doctor’s surgery expecting the GP to advise her (and me) what should be a reasonable bedtime. I know she was disappointed by his response. ‘She’ll sleep when she’s tired.’

When we got home, she told my father in an exasperated tone, ‘Well, he was only a locum. What would he know?’

An American psychiatrist I met many years later suggested I may have had Oppositional Defiant Disorder. I retorted, ‘No, I don’t! I’ve just always been difficult.’

My mother certainly seemed to think so, but my father didn’t share her views. He would let me stay up late sometimes. Like the night we saw in the first Labour government in more than a decade when I was nine years old, and the night we watched Ken Loach’s Cathy Come Home to the very end where Cathy and her husband are driven apart by their homelessness. Those evenings, one jubilant and the other sad, helped determine the person I am today. I desperately want a happy ending but learned early that dreams rarely come true. I’ve always had this strange feeling that I must make each day last as long as possible, but a part of me can’t wait for the next to come.

When I discovered that I had a serious physical illness too, just after I retired, part of me declared she was going to work so hard at being healthy that she would keep the disease at bay . . . but I cannot control it, that is not possible, and I do not want to replace one all-consuming way of living with another. I have irritable bowel syndrome. Almost certainly this is related to anxiety, and the Lithium I took for mood problems has knocked out my thyroid gland, so I take thyroxine every day. If I’m not taking enough, I slow down and put on weight.

In those last few years at work, I had a creeping suspicion that I wasn’t paying enough attention to my body. I didn’t smoke and had a reasonably healthy diet, but was overweight, drank alcohol over the healthy limit for a woman and rarely took exercise. I suspected that taking better care would help to manage the exhaustion that enveloped me every evening and at the weekends, when I slept during the afternoons. None of that stopped me abusing my body, and now she is getting her own back. Little by little I became a person with chronic physical health problems, one, two and more . . . to add to the on-going instability of my mood.

After giving up my regular job I found myself half-awake in an operating theatre for the third time in two years. There was an odd familiarity about it from my younger days as a medical student. The smell of the antiseptic hand wash; the immodest gown; the paper thin, cold, smoothness of hospital sheets. I was having a cystoscopy, a rather unpleasant procedure in which they put a tube inside you and have a look at your bladder. One thing about being a doctor is that other medics you consult about your insides always want to show off how their investigative toys work, and they think that because of your qualification you will be keen to see your own insides too.

‘Take a look here,’ the surgeon demanded. ‘That’s the bladder wall.’

To my surprise and relief everything looked fine, smooth and pink. Although I wouldn’t have known whether there was something interesting to see, I was quite prepared to take the surgeon’s word. He turned to put up some pictures which were from that morning’s scan and for a few moments there was complete silence apart from the clattering of the nurses preparing for the next case.

‘It’s not cancer or a stone that’s been causing the blood in your urine, but there probably is still an infection there.’

‘Nothing else to see as you came out of the bladder?’ I had been revising my urogynaecology on the internet.

‘It all looked fine but, actually, looking at the scans, I think you have polycystic kidneys.’ He didn’t sound particularly concerned, just satisfied to have made a diagnosis.

I struggled to remember what that meant and the significance of it. The trouble with being medically qualified is that people assume you have a degree of knowledge which, if you are not a GP or a specialist in that area you’ve probably put in a locked filing cabinet at the back of your mind never to be reopened; or you still access it occasionally but, in my case at least, the notes are nearly forty years old and browning around the edges.

Ultrasound on the same day suggested the presence of cysts in both kidneys and liver. The radiology report suggested that one kidney was enlarged. Or at least that was what the surgeon said. I couldn’t make out anything from the image on the screen. ‘You’ll have to go and see the Renal people,’ he said as the nurses wheeled me into the recovery room.