11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

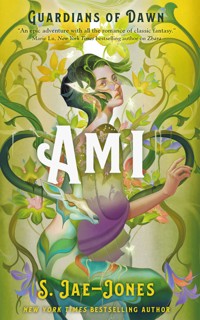

Sailor Moon meets Beauty and the Beast in Guardians of Dawn: Ami, the second book in a new, richly imagined fantasy series from S. Jae-Jones, the New York Times bestselling author of Wintersong. When the Pillar blooms, the end of the world is not far behind. Li Ami was always on the outside―outside of family, outside of friendships, outside of ordinary magic. The odd and eccentric daughter of a former imperial magician, she has devoted her life to books because she finds them easier to read than people. Exiled to the outermost west of the Morning Realms, Ami has become the sole caretaker of her mentally ill father, whose rantings and ravings may be more than mere ramblings; they may be part of a dire prophecy. When her father is arrested for trespassing and stealing a branch from the sacred tree of the local monastery, Ami offers herself to the mysterious Beast in the castle, who is in need of someone who can translate a forbidden magical text and find a cure for the mysterious blight that is affecting the harvest of the land. Meanwhile, as signs of magical corruption arise throughout the Morning Realms, Jin Zhara begins to realize that she might be out of her element. She may have defeated a demon lord and uncovered her identity as the Guardian of Fire, but she'll be more than outmatched in the coming elemental battle against the Mother of Ten Thousand Demons…unless she can find the other Guardians of Dawn. Her magic is no match for the growing tide of undead, and she needs the Guardian of Wood with power over life and death in order to defeat the revenants razing the countryside. The threat of the Mother of Ten Thousand Demons looms larger by the day, and the tenuous peace holding the Morning Realms together is beginning to unravel. Ami and Zhara must journey to the Root of the World in order to seal the demon portal that may have opened there and restore balance to an increasingly chaotic world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part 1: The Pillar

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Part 2: The Root of the World

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Part 3: The Star of Radiance

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

Epilogue

In The Lands of the Bitterest North . . .

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for the Guardians of Dawn Series

“There is something warm and nostalgic about this story that reminds me of my childhood—lush worldbuilding, a charismatic cast, and an epic adventure with all the romance of classic fantasy. This is the kind of book you curl up with in a good armchair, with a favorite blanket and a big mug of tea.”

MARIE LU, NEW YORK TIMESBESTSELLING AUTHOR OFSTARS AND SMOKE

“A treasure of a book that combines spellbinding fantasy with wit, charm, and a heartwarming romance. Nods to beloved fairy tales and fandoms blend seamlessly with demon possession and dark magic, creating a read that isboth joyful and riveting. I can’t wait to see what other surprises this series has in store!”

MARISSA MEYER, NEW YORK TIMESBESTSELLING AUTHOR OF THE LUNAR CHRONICLES

“The kind of fantasy that first made me a reader. Tender and bewitching, joyous and thoroughly transporting… S. Jae-Jones weaves a spell on every page.”

ROSHANI CHOKSHI, NEW YORK TIMESBESTSELLING AUTHOR OFTHE GILDED WOLVESANDARU SHAH

“Jae-Jones takes on Cinderella with magic and style, breathing new life into all the best parts of the story. An outstanding spin on a well-loved classic.”

E.K. JOHNSTON, NEW YORK TIMESBESTSELLING AUTHOR OFSTAR WARS: QUEEN’S SHADOW

“Jae-Jones has successfully captured the magic that infused the animes of my childhood with life and depth and breathed it into this gorgeous young adult fantasy… In a world so complexly built that one could visit, if only they dared. A beautifully crafted story that will set your soul soaring and heart racing!”

KAT CHO, NEW YORK TIMESBESTSELLING AUTHOR OFONCE UPON A K-PROM

“Jae-Jones has done it again! Guardians of Dawn: Zhara is a new entry into the fantasy pantheon I’ve been waiting for. Every reader can find something to love in this first installment of a sure to be monumental and vastly important series. I cannot wait to read more!”

KOSOKO JACKSON, AUTHOR OFYESTERDAY IS HISTORY

Also by S. Jae-Jonesand available from Titan Books

Wintersong

Shadowsong

THE GUARDIANS OF DAWN SERIES

Zhara

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Guardians of Dawn: Ami

Paperback edition ISBN: 9781803365428

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803365435

Illumicrate edition ISBN: 9781835411698

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: August 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© S. Jae-Jones 2024.

S. Jae-Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Lemon,who has read more words of minethan literally any other personin the world

May your good deeds return to you thousandfold.

—Way of saying thanksamong the Free Peoples of the West

PART

THE PILLAR

1

On the eighth day of the osmanthus month, Ami’s fairy tree unexpectedly produced a miniature flower.

It was the fragrance that caught her attention first—a rich, subtly musky perfume that brightened the heavy animal smells of livestock and overripe humans in Kalantze’s village square. Ami set down her begging bowl and picked up the tiny brass vase containing the fairy tree. She touched a gentle fingertip to the delicate white petals, letting her magic mingle with the plant’s ki. “Little Mother,” she murmured. The tree shivered and shimmered as another minuscule bud emerged, quivered, and blossomed in the blink of an eye.

“Doom!” Beside her on their shared woven blanket, Ami’s father preached his usual dire prophecies to anyone who would listen. “Doom upon all the world!”

Although the villagers of Kalantze had long since learned to ignore Li Er-Shuan’s dire rantings and ravings, a few pilgrims who had come to pray before the Pillar eyed him askance. Nearby, a handful of castle guards on their rounds paused, ever watchful for signs of unrest.

“Shush, baba,” Ami murmured, eyeing the guards. “Not now.” She picked up her begging bowl once more and adjusted the wooden sign propped up against her legs. SCRIVENER, it read, in three different languages—the syllabary of the common tongue, the alphabet of the Azure Isles, and the Language of Flowers. Beside her, Little Mother produced another bloom.

“Rinqi?” Li Er-Shuan sniffed the air in surprise. “You haven’t worn that perfume in years, darling.”

Ami flinched as her father’s gaze met hers and flitted away again without recognition. “Ami, Ami, I’m Ami,” she reminded him through clenched teeth. “Mama’s been dead for twelve years.”

A misty expression crossed Li Er-Shuan’s face as he struggled to reorder his mind and find the correct moment in time. Ever since the two of them fled Zanhei, he had become increasingly unmoored from the present, forever wandering the halls of memory or the branching pathways of the future. “Oh,” he said vaguely. “I forgot.”

Ami pushed her glasses up her nose and sighed. “Alms, alms for the needy,” she called, tapping the side of her begging bowl with her knuckles. She nodded her head at the passing pilgrims, trying her best to ignore their pity.

There wasn’t much use for a scribe’s services in the remotest parts of the Zanqi Plateau—the Free Peoples had their own systems of writing, if they were literate at all—but it was all she had left to sell. Most refugees from other parts of the Morning Realms had not stayed long in Kalantze, either young and able-bodied enough to travel with the nomadic clans as apprentice or itinerant magicians or else skilled in some way aside from magic that allowed them to adapt or assist with the way of life in the outermost west. Woodworkers. Weavers. Herbalists. Healers. Hunters. Only the very old, the very young, the disabled, the infirm, and the useless were left behind to survive on charity—begging for grace in the village square. Like Li Er-Shuan. Like the orphans of the Just War.

Like her.

“Doom!” Li Er-Shuan bellowed. “The Guardians awake and demons walk among us!”

“Baba,” Ami pleaded, looking toward the castle guard once more. Their increased presence in the village set her teeth on edge, the memory of black wings etched onto leather sleeves ground into the over-tight muscles of her jaw. But these guards were no Kestrels; they were merely dispatched from the nearby fortress-monastery of Castle Dzong to protect villagers from the growing crowd of restless pilgrims come from far and wide to pray before the Pillar.

“When the Pillar blooms,” Li Er-Shuan called, “the end of the world is not far behind.”

One of the pilgrims, a tall yak-herder with a gold devotional shawl about their neck, gave the astrologer a sharp glance. At their feet, a small child peered at Ami with a curiously flat gaze that lifted all the hairs on the back of her neck. Her magic tingled, itching like a rash. “The Pillar has bloomed?” the yak-herder asked fearfully. “But the sacred tree has not blossomed in over two thousand years!”

A ripple of anxiety fluttered through the crowd. “The Pillar, the Pillar,” the pilgrims murmured. “Why won’t the Qirin Tulku let us pray before the Pillar?”

For the past several weeks, the gates of Castle Dzong had been shut to any and all supplicants seeking solace before the most sacred relic in the realm. The Pillar was the only living sapling of the mythical Root of the World, also known as the tree of life. Stories and rumors had run rampant throughout the streets of Kalantze as to the reasons why, and the mood of those encamped in the village was tense and volatile, like tinder just waiting for a spark.

“Proof!” Li Er-Shuan moaned. “We need proof.” He clutched a leather folio filled with papers and notes to his chest. “For though it is written in the stars and in the book, we must see the Pillar for ourselves!”

The crowd murmured in restless agreement.

“Ho, beauty,” said the nearest guard. Raldri, one of the youngest members of the castle guard, and the only one she knew by name. He was a familiar face around the refugee shantytown after sundown. “Keep that old man of yours quiet lest we arrest him for disturbing the peace.”

Ami bowed her head and kept her gaze lowered. “Of course, Excellency.”

Raldri said nothing, and she could feel his eyes on the back of her neck like the burning rays of a too-hot sun. “No need to be so formal with me, beauty,” he said in an entirely different tone of voice.

She didn’t respond. She never knew how to respond in the proper way and had learned long ago that silence was better than erring.

The guard stepped closer and knelt down before her. “Business is slow, I take it?” he asked. “Tell you what, I’ll give you a coin in exchange for a kiss.”

Ami furrowed her brows. “No.”

“You’re no fun.” Raldri pushed out his lower lip in a pout, but his eyes were hard. The mismatch made everything he said and did feel like a lie. It made Ami squirm with discomfort, her magic writhing in her chest in warning. He crouched down beside her with a grin, teeth flashing white. “Don’t you find me handsome?”

He was so close she could smell the sharp stink of old sweat and stale beer beneath the champaca and cinnamon perfume oils he wore. “I acknowledge that Raldri’s features are symmetrical and balanced,” she said, leaning back and trying to create space between them without having to get to her feet, “which other people find attractive.” It wasn’t a lie, and Ami didn’t think Raldri would find offense in the statement.

“You’re an odd one.” His smile grew wider, even as his eyes grew meaner. “Beautiful, but odd.” He reached for the spectacles on her face. “And you’d be prettier without those on, owl eyes.”

She ducked her head, partially to avoid his touch, partially to hide the green-gold glow blooming about her cheeks. “But I can’t see without them.” Ami picked up Little Mother’s bowl from the blanket, turning it round and round and round, letting her overworked magic unspool into the fairy tree’s ki pathways. Three more miniature flowers blossomed in Little Mother’s tiny branches, bursting like tiny fireworks against a dark green canopy.

“Raldri.” A gloved hand came down hard on the guard’s shoulder and pulled him aside. “Enough.” A short, slim youth in the nondescript brown tunic and trousers of the castle barracks stood behind him, a stern expression on their scarred face. “Your attention is unwanted.”

Raldri scoffed as he got to his feet. “My attentions are always wanted. It’s not my fault you have a face like a cowpat.”

The left side of the stranger’s face was mottled and twisted with uneven flesh, a crescent moon of burned tissue curving down from above the brow to end at their lips, pulling one side up into a perpetual smirk. Theirs was not a beautiful face by any objective standard, but neither were they displeasing to the eye. The stranger caught Ami’s gaze and smiled. It matched the kindness in their gaze.

“And it’s not my fault you have the personality of yak cud,” they said, pushing Raldri down the path ahead of them. Although the scarred youth stood nearly a head shorter than the other guard, they radiated such a sense of calm authority and charisma that Raldri complied without protest. “Go. We’ve got rounds to make.” They gave Ami a wink as they left.

She set down Little Mother and picked up her begging bowl again. “Alms, alms for the needy.”

“Here.” The tall yak-herder dropped a few coins into her begging bowl. “May the Wheel turn and fortune smile upon you again soon.” Their eyes slid to Li Er-Shuan, who had ceased preaching and was now frantically scribbling notes on the pages in his folio.

Ami lifted the bowl and pressed it to her forehead as she bowed. “A thousand, thousand thanks, kind stranger.”

The yak-herder shook their head with a soft laugh. “We don’t hold with that fancy hierarchy nonsense the rest of you lowlanders like to sprinkle into your speech,” they said. “Be easy, friend, and take care of yourself.”

Back home in Zanhei, she had been too blunt. Here in the farthermost reaches of the empire, she was too formal. “Thank you,” Ami said again. “May your good deeds return to you thousandfold.” It was the customary response among the followers of the Great Wheel, and one she was still getting used to.

The yak-herder smiled. “Come along, Chen,” they said to the child clinging to their legs. “Let’s see if the Right Hand will grant us passage today, lah?” They glanced up at the fortress built into the outcropping of rock above their heads, the golden flat-topped roofs glinting in the late-morning sun. “Perhaps today will be our lucky day.”

“Not today,” Li Er-Shuan muttered. “The stars say my luck is crossed today.” He squinted into the clear, cloudless sky, as though he could read the heavens hidden by daylight. In a world long since gone, her father had been an imperial astrologer, interpreting the heavens in order to make sense of the events on earth. But the night he fled the imperial city all those years ago, the night he broke his vow of loyalty to the Mugung Emperor and stole a fragment of Songs of Order and Chaos, had shattered his sanity like a flawed vase in a kiln, leaving him a ranting, raving, rambling wreck ever since. “Proof,” he said to himself, frantically scanning the papers spread out before him. “I need proof.”

“Careful, baba.” Ami grabbed several loose sheets before they fluttered away in the breeze.

“Shush,” Li Er-Shuan said impatiently. “I am deciphering the commandments of the gods.”

Ami closed her eyes against the sting of loneliness and resentment burning her lower lashes. She might have lost her mother when she was only four years old, but her father had been lost her entire life. To the stars, to the labyrinth of his fractured mind, and to the past. She carefully tucked the pages back into their folio, a faded leather wrap inscribed with a bisected symbol of concentric circles, half embossed, half engraved.

“Hold!” A deep, booming bass voice rumbled over the crowded square. “I said, hold!”

At the foot of the 888 Steps of Meditation that led up to Castle Dzong, the crowd of pilgrims pressed against an enormous black-skinned man—Captain Okonwe, head of the castle guards—demanding entrance to the fortress.

“The Pillar!” they cried. “Why won’t you let us in to pray before the Pillar?”

“The Qirin Tulku will hear everyone’s petition in due time, never fear.” Beside Captain Okonwe was a slim, stooped figure draped in the sage-green colors of a cleric and a heavy badge of office on an enormous wooden beaded chain. The Right Hand of the Unicorn King, the highest-ranking official in Castle Dzong. “He only asks for everyone’s patience.”

“Patience?” said the tall yak-herder. “My daughter is dying and you ask for patience?”

“Ami-yah,” Li Er-Shuan said. “Hide your light.”

Panic ran ice through her veins as she yanked her magic back beneath her skin, holding it close to her bones. Moments passed, but no Kestrels came to drag them away. All magicians were free in the lands protected by the Unicorn King, but the instincts of a lifetime of terror were hard to overcome.

“Let us in!” the pilgrims demanded. “Why are we left out in the cold while a blight ravages our lands?”

“Blight?” Li Er-Shuan stirred, nervously picking at the skin around his nails. “No, no,” he murmured to himself, “not a blight. A curse. But it’s not in these pages. It’s not in these pages.” Without warning, he scattered the pages of his leather folio in a rage, sending the leaves fluttering in the mountain breeze. “Useless!” he cried. “It’s all useless!”

“Baba!” Ami scrambled to her feet and scrabbled for the loose sheets before they blew away. The notes on Songs of Order and Chaos were Li Er-Shuan’s life’s work, and the only thing holding the last of her father’s sanity together. “Please!” she called to the nearest guard as the papers fluttered down the street. “Raldri!”

Raldri took one look over his shoulder, paused, then continued on as though he had not heard nor seen her. The deliberate, spiteful way he met her gaze, then turned away struck Ami like a slap across the face.

“Here.”

Startled, she turned to find the scarred guard behind her, the scattered pages in hand. Their cheeks were bunched in a smile, evening the mismatched sides of their face into temporary symmetry. They were handsome when they smiled.

Ami gathered the offered pages together with a bow. “May the kind stranger’s good deeds return to them thousandfold.”

The scarred stranger laughed.

She looked up. “Did I get it wrong?”

Their eyes twinkled. “No. It’s just that we’re not so formal here in the outermost west.”

“I know,” Ami said. “I keep forgetting.”

The stranger tilted their head, eyes flitting to the painted sign advertising her services propped up on her blanket. “You would think someone who speaks so many tongues would have a better grasp on different customs.”

She cringed. More times than not, Ami found herself on the outside of social customs, struggling to understand a tongue everyone spoke but her. “Pardon, pardon, a thousand pardons.”

They frowned in confusion. “Why are you apologizing?”

“In case I’ve offended the kind stranger.” It was easier to apologize than keep pretending she understood everyone else’s language. She caught herself. “I mean . . . in case I’ve offended you, friend.”

The scarred youth smiled. “Friend,” they mulled. “I like that.”

“Is that not the right word either?” Ami asked in dismay.

Their smile widened. She liked their smile; it felt honest. “There is no right or wrong,” they said. “Friend.” They bowed. “My name is Gaden.”

Ami returned their courtesy. “Ami,” she said shyly. “Li Ami.” She smiled back.

The tips of Gaden’s ears turned pink and they quickly looked away. Ami remembered to avert her own eyes. People often found her gaze too intense. Just another thing about her that made others uncomfortable, and another reason she preferred to keep her glasses on her face.

“Is this yours as well?” Gaden held a piece of leather in their hands—the folio in which Li Er-Shuan kept his notes.

“Yes, thank you.” Ami tucked her father’s pages into the leather, rolling everything up and wrapping it with a frayed suede cord to keep it closed. She caught sight of Gaden studying the symbol on the folio’s cover.

“That sigil,” Gaden said quietly. “I’ve seen it before. What is it?”

Ami was surprised. “You have? Where?”

They said nothing at first, their gaze searching her face for some answer to a question she did not know. She tried not to show any discomfort; too often people read her discomfort as smugness or hostility, especially if she didn’t understand what was wanted of her.

“In the castle library,” Gaden said at last. “There is a text with this symbol stamped into its cover, just like this.”

All the hairs stood straight on the back of Ami’s neck, tingling in anticipation. “And the pages? What do the pages say?”

Gaden frowned. “I don’t know,” they said. “I can’t read it.” Their eyes flicked to the painted wooden sign boasting SCRIVENER in three different languages. “I know a little bit of the Language of Flowers, but the writing on the pages seems older. More stylized, perhaps.”

The tingles spread down Ami’s spine and limbs. “It is the Language of Flowers!” she said excitedly. “Oh, I would love to see what it says!” The scarred guard took a step back, before Ami remembered to rein in her zeal. She could be overwhelming at times. “Sorry.”

“It’s all right.” They smiled at her. “I find your enthusiasm charming.”

It didn’t sound like a lie. Warmth kindled in Ami’s chest. “May your good deeds return to you thousandfold,” she said, and this time she was certain she had gotten it right.

Gaden bowed, then met her gaze as they straightened. They were both of the same height, she realized, and their eyes were level with each other. Gaden was the first to look away again, and with a sheepish shuffle, they hurried to join the other castle guards patrolling the market square. Ami tucked the folio beneath her arm and headed back to return it to her father, excited to tell him that another fragment of Songs of Order and Chaos had possibly been discovered in the library. His life’s work, and by extension, hers.

Only the blanket was empty.

“Baba?” Ami looked around, unease creeping up her neck, muffling her ears with ringing dread. She rarely left her father unattended, as he had a tendency to frighten those who were unaccustomed to his manic behaviors, but neither was Li Er-Shuan inclined to wander far. “Baba?”

Her father was often easily overwhelmed by a mass of people—their smells, their sounds, their textures, their closeness—unable to handle the tide of sensations that frequently threatened to drown him. The last thing Ami needed was the castle guard arresting him for disorderly conduct again. She had had to borrow butter from one of the barley aunties to pay the bribe last time, and she didn’t want to be any more of a burden on them than she already was.

“Baba!” she called. “Li Er-Shuan!”

But no one responded. No one even gave her a second glance. Ami swallowed, trying to find her voice. She had spent so long hiding that she had not realized how hard it would be to be seen again. Her magic writhed in her chest, but she resisted the temptation to use her power to rifle through the ki of those around her for her father’s.

Hide your light was his oft-repeated refrain. As much as Ami loathed hearing those words, they were the only times he was present with her. Hide your light, lest the others discover what you really are.

She had been called many things her entire life—odd, eccentric, unusual, strange, different—but those words only ever got at the barest hint of what she truly was. The thing that kept her distant and apart from everyone around her, even other magicians. Ami picked up Little Mother from the ground, turning the vase round and round and round in her hands. More and more blossoms bloomed as her power entwined with that of the little tree.

Unnatural.

2

It was impossible to escape the Good-Looking Giggles while traveling with the Bangtan Brothers.

“What’s so funny?” Mihoon, the troupe’s composer, percussionist, and second-oldest member, had been tasked with teaching Zhara how to cast spells, as he was the most patient and practical of the Brothers. He sat beside her in the back of the Bangtan Brothers’ cramped and crowded covered wagon as they worked on her magic lessons, and their physical proximity made Zhara both giddy and giggly.

“N-nothing,” she replied.

Mihoon lifted a sardonic brow, which only made the Giggles worse.

The problem, Zhara decided, was that there were seven of them—Junseo, Bohyun, Mihoon, Sungho, Taeri, Alyosha, and Yoochun. She could handle one good-looking person at a time, perhaps even two, but seven at once was both overwhelming and exhilarating.

“Yah!” came a shout from outside the wagon. “That was my shirt, you fiend of a feline!”

Well, eight people. Zhara sneaked a peek out the back as a half-naked prince tore down the road after a small, gleeful ginger cat. Wonhu Han, the Royal Heir to the throne of Zanhei, had many admirable attributes. His back muscles in particular were quite well-defined.

“Admiring the view?” Mihoon asked drily.

Zhara coughed. “Right, binding spells.” She returned to the torn halves of the mulberry paper before her, her brush poised above the jagged edge. Zhara studied the character for mending in The Thousand-Character Classic, trying to remember the order in which the strokes were drawn. Mihoon held the paper together on the seat between them. Zhara felt her way along the void that existed between all things, and drew.

Nothing happened.

“I must be a dunce,” she groaned. “Why can’t I get this right?”

“You are not a dunce.” Zhara’s cheeks warmed. Mihoon wasn’t especially demonstrative, so any bit of praise—however slight—was incredibly validating. “Some people are good at some things, but not good at others. You could be like Junseo, who easily grasps the most complicated and complex magic but struggles with the simplest spells.”

“If only I had Junseo’s brain,” Zhara muttered. The leader of the Bangtan Brothers, being the quickest and cleverest of the members, had initially been assigned as Zhara’s magic tutor, but they soon discovered that impressive intelligence did not readily translate into equally impressive teaching.

“Some people learn by reading, some people by doing, and still others by watching.” Mihoon gently took the brush from Zhara’s hand and drew the glyph across the torn edges of the paper, his sharp, confident strokes leaving a trail of black light edged with white. The tear sealed itself, and the paper was whole once more. “Here.” Mihoon handed Zhara The Thousand-Character Classic and the sheets of mulberry paper they had been working on. “Keep practicing.”

Zhara sighed and took back her brush, flinching when her fingers brushed the page Mihoon had bespelled.

“Is something the matter?”

Frowning, she lifted the page to the sun. She swore she could see the faintest glimmer of black edged with glittering white where the tear used to be. The color of Mihoon’s magic. “Can you see it?”

“See what?” His arm brushed hers as he leaned in close and Zhara flinched again. “Beg pardon,” Mihoon said, giving her space, but she stopped him with a touch.

“Wait.” Beneath her fingertips, she could sense his ki, the essence that was Mihoon, and realized with a start that she had felt that same essence when she picked up the mended piece of paper. “Here,” she said, placing the page in his hand. “Do you feel it?”

The composer blinked. “What am I supposed to be feeling?”

“The magic.”

He tilted his head at her, much the way Sajah did when he was confused. “I don’t understand.”

“Maybe it doesn’t work if you did the spell,” Zhara said. She leaned out the back of the wagon and hailed the nearest Brother. “Junseo,” she called. “Can I ask you a favor?”

The troupe’s tall, lanky leader jogged up to join them. “What is it?”

Zhara tore a fresh sheet of paper and handed him her brush case. “Can you make this whole again?” she said, holding up both halves.

“Better ask one of the others,” Mihoon advised. “Junseo has a tendency to make things explode. Born with Yuo’s brush in his hand, but his big brain tends to overcomplicate things. Sungho!”

The troupe’s slim stage director popped up beside their leader with a cheery smile. “At your service! How many I help?”

Zhara repeated her instructions and Sungho obliged, his brushstrokes leaving trails of bright red before dissipating as the paper seamlessly mended itself. “Here,” she said, handing the page to Mihoon. “Can you feel it now?”

“Feel what?” Junseo asked.

“Magic, apparently.” Mihoon passed the paper to the leader with a shake of his head. “I don’t feel anything. It just feels like paper to me.”

Junseo studied the sheet and turned it over a few times before handing it back to Zhara. “I don’t feel anything either.”

Again, that startling sensation of resonance—of recognition—flooded her bones. This time the paper felt like Sungho—his bright and sunny disposition, his ambition, and his surprisingly dark inclination toward perfectionism. “It feels . . .” Zhara began, trying to find the right words. “It feels as though Sungho left traces of his ki in the spell.”

Junseo frowned, his chin jutting forward with concentration. “Perhaps sensing ki is a sort of Guardian power,” he mused. Zhara could almost see the quickness of his thoughts flickering behind his eyes. “If a magician’s ability is to manipulate the void,” he murmured, more to himself than to the others, “is a Guardian’s ability to manipulate ki?”

Zhara looked down at the brush in her hand. It had been a gift from Jiyi, one of the members of the Guardians of Dawn back home in Zanhei and a good friend. Huang Jiyi came from a long line of spell-mongers, or people who traced and maintained the etymology of each glyph and occasionally created new ones as necessary. You’re a magician, Jiyi had said. And you should have the tools of one.

But what good was a tool if she couldn’t even use it properly? Zhara tucked her brush back into its case and slid it into her waist-pouch, glancing up at the winged white shape circling overhead. Temur, the Eagle of the North and their ever-present watchful tail. Temur was the celestial companion of Princess Yulana, the other Guardian of Dawn—the elemental warrior, that is. Yuli was the only other person who might help her make sense of elemental powers, but unfortunately, the northern princess was currently en route to Urghud.

Not that it stopped them from communicating. Yuli’s Guardian gift was spirit-walking. She could send her spirit far and wide, or at least wherever Temur happened to be. Once they were settled in Mingnan, Zhara hoped the princess would have time to catch up.

“That blasted cat!” Han returned from chasing Sajah down, still shirtless. “This was my last clean shirt,” he moaned, holding up a stained and crumpled piece of fabric. “And Sajah peed all over it.”

“Well, they say animals pee on things when they’re feeling territorial,” Mihoon remarked.

“Are you saying Sajah thinks of me as his property?” Han asked with dismay.

The barest hint of a smile twitched at the corner of Mihoon’s lips before they smoothed back into an expressionless line.

Han sighed. “Can I borrow a spare shirt, gogo?” He had quickly fallen into the habit of calling the members brother, adopting an easy intimacy with them that Zhara sometimes envied. With her, the Bangtan Brothers were nothing but polite and ever-so-slightly distant, as though she were the noble and Han the commoner.

“Your biceps will burst the sleeves to shreds,” Sungho said to the prince, even as Mihoon began rummaging through his things.

“You could also just go shirtless until we get to Mingnan,” Zhara remarked, opening up the canvas flaps at the back of the wagon. Mingnan was the largest of the border towns along the foothills of the Zanqi Plateau that dominated the western part of the empire, the last stop on the road before entering the lands ruled by the Unicorn King. “Some of us wouldn’t mind the view.”

Han startled to see Zhara twinkling at him. “Oh,” he said, flushing a deep plum red, hands scrabbling to cover his bare chest. “I, er—haha,” he said, voice cracking. “Um, so—”

“Oh, just take it, Master Plum Blossom.” Mihoon tossed his shirt at Han, where it landed on his head. “Spare me your maidenly blushes.”

Zhara politely averted her gaze as Han got dressed, swallowing down the temptation to tease him. There was very little privacy on the road, which made Han’s inherent modesty both adorable and just a little bit frustrating. She had hoped that once the other refugees from Zanhei left their party, he would open up, but if anything, their increased proximity had turned him even more shy. Zhara touched the rose quartz bangle around her wrist.

Rrrrrip!

“Mother of Demons!” Han looked sheepish as he fingered the shredded sleeves about his arms. “Sorry, gogo,” he said to Mihoon. “I’ll buy you a new shirt.”

“Mah!” came a voice from the front of the wagon. Taeri, the third Choi brother and the group’s main tumbler, sat on the driver’s bench, directing their elderly nag, Cloud, along the road. “There’s Mingnan!”

As the group crested the hill, a river valley plain came into view, a glittering ribbon of silver running down the foothills of the Gunung Mountains straight ahead to the west. Nestled in an emerald-green pine forest was a collection of brightly painted roofs, scattered among the canopy like gems in a mine. Unlike the walled cities of the south, Mingnan had no stone borders but the sheer cliffs on either side of the river tributary on which it had been built. There were no walls, no watchtowers, nothing that marked the boundaries of the border town, so different from the carefully constructed cities of the south and east. Strung in the treetops were lines of prayer flags, carrying wishes from the people to the ears of the heavenly Immortals. Prayer flags were not common in Zanhei, but Zhara had seen more and more of them on the road to Mingnan, as they drew nearer to the land of the Qirin Tulku and the Free Peoples of the outermost west.

The Bangtan Brothers gave a cheer at the sight of the jewel-colored roofs and Sungho began clapping. “We’re here, we’re here, the good time boys are here!” he chanted. “We’re here, we’re here, the good time boys are here!”

The others immediately took up the song. “Good! (Good!) Time! (Time!) Good! (Good!) Time! (Time!) Come now join in our shine!”

Everyone’s spirits were high as they drew ever closer to Mingnan. The road had been long, dusty, dirty, and occasionally dangerous, with bandits and Kestrels to avoid. Thankfully, they had not encountered any abominations along the way, although they had come across rumors of other . . . unnatural and uncanny encounters. Stories of hungry ghosts devouring the souls of the living, tales of empty cairns and tombs, of the dead rising once again. But thus far, the rumors were just that—rumors. Information to bring to the Guardians of Dawn once they reached the safe house.

“I’m starving,” Yoochun said, rubbing his stomach plaintively. Youngest though he might have been, Yoochun was also the biggest member of the Bangtan Brothers, a rapidly growing boy of fourteen who—despite his well-developed muscles and surprising height—had the lean, hungry look of a child who never got enough to eat. Zhara had been sneaking him part of her road rations at almost every meal, only to discover that everyone else was secretly doing the same. “The first thing I’m going to do when we get to the safe house is eat twenty bowls of Mingnan’s famous red sauce noodles,” he declared.

“I heard all the food in Mingnan is red,” Taeri said. The region was famous for its ice-fire peppers, which were said to tingle the taste buds with a numbing sensation. “Anyone want to place wagers on who can win the title Sovereign of Spice? Loser has to dig the latrines wherever we camp next.”

“I’m out,” said Sungho. “I can’t handle spicy food.”

“Same, same,” said Alyosha. Mihoon and Bohyun, the eldest, also demurred.

“I thought all Azureans had a high tolerance for spice.” Zhara grinned. “I’m in.”

“Not me,” Han said. “I value my guts too highly for that.”

The prospect of a hot meal after weeks of road rations—rice and fermented soybeans supplemented with whatever game they could catch and greens they could forage—raised everyone’s mood. “I hear the Le sisters keep a good table,” Junseo said. “We should be in for a treat.”

“The Le sisters?” Zhara asked.

“They run the Guardians’ safe house in Mingnan,” the leader said. “A message outpost on the outskirts of town.”

“Message outpost?” Zhara was disappointed. She had hoped it was a bathhouse. They could all use a good scrub. Even Sajah was starting to smell rather ripe, and he was an immortal celestial animal companion. This close to the source of the Red River, the waters were a fast-flowing, creamy turquoise, rich with the mineral smell of hot springs and steam. The border towns along the foothills of the Gunung Mountains were famous for the natural baths, and as they approached the freestanding vermillion gates to Mingnan, Zhara didn’t know what she was looking forward to the most—a hot meal, a bed, or a bath.

The group fell into comfortable silence as they traveled down the river valley and along the riverbanks toward the town itself. The western bank rose sharply into sheer black cliffs as the foothills gave way to the Gunung Mountains themselves, the border between the Zanqi Plateau and the rest of the Morning Realms. Zhara craned her neck, trying to envision what the lands of the outermost west looked like on the other side. On the maps of the empire she had seen, the Zanqi Plateau was a vast plain of highland pastures and snowcapped glacier peaks, nearly as large in mass as all the other provinces put together. The prospect of trying to find Li Er-Shuan within miles upon miles upon miles upon miles of land was overwhelming, so she tried not to think about it.

“One step at a time,” she said quietly. “One step at a time.”

The Bangtan Brothers’ covered wagon stuttered to a sudden stop.

“Mah!” Mihoon pulled the curtain aside to peer outside. “What’s going on?”

“Shh, shh, shh.” Alyosha stood by Cloud, stroking her nose and murmuring in her ear. “What’s wrong, girl?”

The troupe’s faithful old nag was trying to back out of her harness, the whites about her eyes visible with fear. Not even the second-youngest Brother’s soothing words could calm her, and he was the group’s most effective hostler. In Zhara’s lap, all the hairs on Sajah’s back stood on end, his tail puffed out with alarm. Lightning flickered in the depths of his golden eyes, and a ripple of flame stirred the edges of his fur. Within a blink, the cat transformed into a red bird and fluttered out the back of the wagon, disappearing into the forest outside.

“Yah!” Alyosha cried, and the cart shuddered. “What—”

Zhara crawled out of the wagon with Mihoon to see Cloud galloping away as well, dragging the hitch behind her. The ordinarily placid nag had somehow managed to kick herself free of the cart, and was running away faster than Zhara had ever seen her move.

“Cloud!” Alyosha started after her, but Bohyun stopped him with a warning hand, giving a subtle shake of his head.

“Hold.” Junseo held up a fist, reaching into his sash for his brush with his other hand. The Brothers all pulled out their brushes, and Han slid a bo staff out from the back of the cart, gripping it easily in both hands. Slowly, hesitantly, Zhara pulled her own brush out from its case, but it felt awkward and stiff between her fingers.

The leader pressed a finger to his lips and cocked his head, listening to sounds in the woods. Zhara strained her ears, but couldn’t hear anything.

Then she realized that what she was hearing was nothing. No birdsong, no late-summer cicadas, no distant sounds of life at all coming from either the town up ahead or the forest behind. The silence was heavy, dense, and unnatural.

Junseo nodded, and they all followed quietly behind him on foot, passing beneath the freestanding vermillion gates that marked the entrance to Mingnan. The town was empty—no people, no livestock, nothing but cobwebs and gathering dust.

“What happened here?” Zhara breathed. The buildings and storefronts were mostly undamaged, and it didn’t appear as though the border town had fallen prey to attack. Looters and bandits had made off with valuables a while past, judging by the broken windows and doors, but apparently Mingnan had been abandoned long before opportunists came to scour the place clean.

“Sickness?” Sungho asked fearfully. He had his nose buried in the crook of his free arm, brush hand shaking. “Some sort of plague?”

“Maybe.” Junseo frowned, pulling his shirt over his nose and mouth. “Does anyone else smell that?”

Zhara sniffed, then coughed. A strange, almost sickly-sweet scent hovered in the air, coating the back of her throat like chalk. It was the smell of spoiled meat, of something rotten, of decay and death.

Yoochun wrinkled his nose. “It smells like an abattoir,” he said.

Han gripped his bo staff even tighter, slowly moving his feet into a defensive stance. “Something’s not right here,” he said in a low voice. “It all feels very . . . ghoulish.”

And that was when the undead attacked.

3

The sun was starting to slip beneath the horizon, but Li Er-Shuan was still nowhere to be found.

Kalantze wasn’t a large settlement, and there weren’t many places a small, frail southerner could go without standing out like a weed among wildflowers. Ami had gone to each public establishment several times over, asking for her father, but each time, no one could remember having seen him, and Li Er-Shuan was anything but forgettable. He was a thin, bald-headed, birdlike figure with thick black spectacles that made his eyes seem enormous and owlish, frequently flapping around Kalantze’s market square in oversize robes . . . if he remembered to clothe himself at all. On ordinary days, Li Er-Shuan’s wandering off would be concerning enough, but Ami couldn’t help but think of Raldri’s veiled threat earlier. Her father’s fragile wits could scarcely manage the sights and sounds of Kalantze; imprisonment would break him entirely.

Perhaps he had gone home. Ami packed her things and made the hike down to the refugee settlement at the foot of Grombo Hill, trying to remain hopeful. Perhaps one of the barley aunties had found him and brought him to their little shanty on the outskirts.

But he wasn’t there either.

“Maybe your father is out in the fields?” one of the barley aunties suggested unhelpfully. She sat with the others on a woven mat atop a wooden platform, sorting and bundling together stalks of barley for threshing. “Helping with the harvest?”

Li Er-Shuan had never once performed a day’s work, not manual labor, at any rate. She wasn’t sure she would trust him with a sickle in his hand either, even if he knew what to do with it. Her father had never handled a tool less refined than a scholar’s brush even before his mind was broken. Most refugees coming into Kalantze worked in the barley fields to start—tilling, planting, cultivating, harvesting, milling—before moving on to other situations in the lands of the outermost west. Ami had done her share of work in the Poha Plain with the others when she first arrived, but her father’s unique caretaking needs had taken precedence. The barley aunties had all been so kind and so gracious and so supportive that guilt still burned her throat like bile whenever they spoke to her.

“We’ve got enough hands working the yield,” said Auntie Tsong. She was the oldest of the barley aunties, and the kindest, the one who always made sure they had enough to eat, even though neither Ami nor her father had been able to meaningfully contribute to the village resources. “A full third of the harvest is gone.”

Ami was taken aback. “A whole third?” She glanced at the rippling beige waves surrounding them, plains of grain on which the village depended to survive through the long, harsh winters on the Zanqi Plateau. Bits of gray and black curled in from the edges of farmland—crumbling and rotten barley stalks, the unmistakable signs of a blight. “Will there be enough for everyone come winter?”

There was no answer. The specter of starvation hovered over every exchange, every conversation in recent days. It was the reason pilgrims had been pouring in from all over the outermost west and even from the border towns in the Gunung Mountains, each hoping to pray before the Pillar. Ami thought of the yak-herder and his strangely listless daughter, Chen. Perhaps the child’s listlessness had been due to hunger. Pity twisted Ami’s stomach with sympathetic pangs.

“What are you going to do about your father?” Auntie Tsong asked. “Shall we send a search party?”

“No, no,” Ami demurred. “I don’t want to trouble you. My father is my responsibility.”

Auntie Tsong’s lips thinned. “Burdens are meant to be shared,” she said gently. “We must do all we can to look out for each other.”

It was one thing to share burdens with others, and another thing to be the burden. “Please don’t waste your time on our account,” Ami said. “I’ll return to the village and keep looking.” She picked up one of the blighted stalks from the woven mats and bid a hasty retreat, steeling herself to make the climb back up to the village. Although Ami had long since grown accustomed to the thinness of the air atop the Zanqi Plateau, the path up to the village was not an easy one to make on an empty stomach.

She wiped away the sweat that trickled down her brow as she studied the barley in her hand. At first glance, it seemed merely rotten—the golden brown of its stalks and grain turned ashen and gray. Brittle, almost like stone. Petrified, yet still living.

Curious, she probed the stalk with her magic, seeking its ki the way she did so effortlessly with Little Mother.

Ever since she was a little girl, Ami had been able to twine her power with the threads of ki that bound the world together. It was easier to do with the living: their ki was vivid and bright and easy to find with her magical senses. If the ki was weak or thin, she could fill the emptiness with her power, like water filling a vessel. Ami had used her gift to help the herbs and flowers of their garden grow back home in Zanhei; perhaps she could do it with the barley now. Concentrating, she let her magic flow from her veins to the stalk in her hand, finding the wounds her power could heal within the plant, enveloping the little branch in a green-gold glow.

With a hiss, Ami dropped the barley plant in shock.

For a moment, it was as though her magical senses had been entirely snuffed out, as though someone had flashed her eyes too quickly with a bright light and now everything was dark. Only instead of light, whatever was within the barley plant was the complete absence of light—a dark so opaque it almost hurt. It pulled at more than her power; it pulled at her very soul. Her ki.

And now her magic was numb. Ami tried to call forth her power, but there was nothing. Although she still had use of her physical eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and touch, she felt as though she had lost some vital, crucial part of herself with which she had navigated the world. “No,” she murmured, tugging at the skin of her lip over and over again, to remind herself that she could still feel, that she was still alive. “No, please.” She tried to bring up her magic, but there was nothing. No light, no glow, no warmth. “Please.”

Clang, clang, clang, clang.

The sudden clamor of bronze sent Ami clapping her hands over her ears, her entire body ringing with alarm. Waves of terror washed over her again and again and again, and she crouched down in the middle of the path, just within view of the village gates. Unable to feel her magic, she felt strangely vulnerable to every sensation, as though experiencing the entire world anew. Everything was raw. Everything hurt. She wrapped her arms about her middle, where Little Mother was tucked into a blanket tied about her waist.

“Are you all right, friend?” It was the yak-herder with his dead-eyed child.

Ami gritted her teeth and nodded, swallowing down the tongue that seemed to have suddenly swollen in her mouth. In her hands, Little Mother stirred and produced another flower. Little by little, her power began to return and Ami felt herself inhabit her body again as the same soul, the same ki she always was.

“Friend?” The yak-herder placed a gentle hand on her shoulder. “Are you all right?”

Ami startled at their touch as her power roared back to life, coursing through her veins again. “Yes,” she gasped. “Yes, yes, a thousand thanks.”

“I didn’t even do anything.” The yak-herder looked amused. They pressed their palms together and touched their thumbs to their nose, sticking out their tongue in greeting in the manner of the Free Peoples. “My name is Sang, Chen’s father, should you need a friend.” It was the customary greeting of the plateau peoples.

Ami bowed in return, hands held out before her in the southern style. “And I am Li Ami, should Sang need a friend.” She glanced at Chen, but the little girl did not seem inclined to introduce herself. Instead, her eyes were fixed on the fairy tree in Ami’s hands with an expression almost akin to fear.

The yak-herder grinned. “We’ll break you of that habit of formality yet, scrivener.” He glanced up at the castle towering over Kalantze. “Do you know what all this bell-ringing is about?”

Ami shook her head. Unlike the watchtower drums of Zanhei, ordered and predictable with their own rhythms and patterns to signal fire or invasion or plague, the bells of Kalantze rang for any occasion: happy, sad, terrifying, and trivial. “The bells could signal danger,” she said. “Or the announcement of a betrothal. The only way to find out is to gather in the square and wait for someone to step on the crier’s platform.”

“Well then,” said Sang. “Lead the way, Li Ami.”

By the time Ami, Sang, and Chen arrived at the market square, a vast crowd had already gathered, scarcely leaving any room for stragglers. Ami took the opportunity to scan the assembly for her father, hoping he too had heeded the call to gather. But his distinctive bald pate and owl spectacles were nowhere to be found, and her heart sank with both dread and disappointment.

“What’s going on?” people murmured to one another when several moments passed and no one stepped onto the crier’s platform. “Why have we been called here?”

“I heard they caught someone trespassing in Castle Dzong,” someone else replied.

“Kkgggghh.” Another made a guttural sound of disapproval. “That would be exile. Who would risk that? It’s hard enough surviving out there with a whole clan around you. You wouldn’t last long on your own.”

“Especially with the undead prowling about,” Sang muttered beside Ami.

She gave the yak-herder a sharp glance. “The undead?”

Sang’s lips tightened, along with his grip around Chen’s arm. “I know what it is I saw,” he said. “And my own daughter bears the marks of their violence. Don’t tell me the dead coming back to life is impossible; I’ve heard it enough already.”

Ami frowned. “But I wasn’t going to—”

“Look!” came a voice from the front of the crowd. “The sages!”

All heads turned to the 888 Steps of Meditation, where a procession of clerics in sage-colored robes was making its way from the castle gates to the village square. At the head of the procession was the Right Hand of the Qirin Tulku, the highest-ranking cleric in the castle and the shaman-king’s emissary to the public. Following behind was Captain Okonwe, instantly recognizable by the color of his dark skin and the breadth of his shoulders. Beside him was a guard in some sort of animal or ritualistic mask, and between them, a frail, stumbling figure limped along with their hands bound. Cold, icy unease dripped down Ami’s back; the prisoner was bald. She squinted as she pushed her glasses farther up her nose, trying to make out their features from afar.

“The Right Hand,” Sang said gratefully. “Perhaps the Qirin Tulku has relented and will let us pilgrims enter hallowed ground to pray before the Pillar at last.”

“I doubt that,” said another pilgrim to Ami’s right. “Do you see the masked guard beside the captain? That’s the Left Hand of the Qirin Tulku.”

A chill deeper than the growing cold descended over Ami’s shoulders. They said the Qirin Tulku had two Hands to do his bidding: the Right Hand to write the sentence, and the Left Hand to execute it. Unlike the Right Hand, the Left Hand was not a cleric, which allowed them to dirty their hands with death. And unlike the Right Hand, whose face was known to the public, the Left Hand wore a wooden mask carved with the features of a boar chimera to hide their face.

Sang sucked in a sharp breath. “The Beast?”

Ami knew little about the Beast, although rumors ran rampant among the pilgrims and refugees. The Beast was a tame demon, a fairy servant from the otherworld, the true inheritor of the Sunburst Throne. They wore a mask because they were monstrously ugly, or to hide their fairy marks—feathers for hair or tiger eyes or a blue tongue. Ami knew little about the Beast, but she did know one thing.

Their presence never presaged anything good.

The procession had reached the crier’s platform at the bottom of the 888 Steps, and with sudden, awful clarity, Ami finally understood where her father had been all day.

“Doom!” Li Er-Shuan moaned as Okonwe and the Beast pushed him onto the crier’s platform. “Doom upon all the world! Beware, for when the Pillar blooms, the end of the world is not far behind!”

The Right Hand waited until Ami’s father had fallen to his knees before raising his hands for silence from the crowd. “Hear my voice and heed my words, one and all,” the cleric said in a thin, reedy voice that did not carry. “This knave kneeling before me stands accused of trespassing on hallowed ground and defiling a sacred object.”

A ripple of confusion stirred the crowd. Behind the Right Hand came a soft cough.

“Defilement of a sacred object can only be a crime if sacrilege is a crime.” It was the Beast. Unlike their counterpart’s, their quiet voice did carry over the crowd—light, husky, and oddly familiar to Ami. “Sacrilege does not exist in the teachings of the Great Wheel.” The Beast tilted their head. “But surely the Right Hand would know this.”

The cleric glowered at the Beast. “Desecration of castle property,” they amended. The Right Hand lifted their arm high above their head, holding what appeared to be a twig capped with a cascade of pure white star-shaped blossoms. “Behold this branch taken from the Pillar by”—they brandished the twig at Li Er-Shuan—“this cowering criminal!”

There was a collective gasp of shock from the assembled. “The Pillar,” they murmured. “The holy tree.” The crowd stirred, becoming restless and agitated. Ami clutched Little Mother tighter to her chest, trying her best to keep her nerves contained. She had not anticipated this; why had she not anticipated this? How could she have been better prepared?

“I would hardly call picking a flower from a tree an act of desecration,” the Beast remarked in a mild voice.

The Right Hand gave a strangled squawk of frustration. “I would remind you,” the cleric said icily. “That I pass the sentence and you execute it, Beast.”

The masked guard gave a slight nod of their head. “I apologize, Jetsan,” they said. “Pray, continue.”

The cleric cleared their throat. “For the crime of trespass and desecration,” they went on, “I sentence you, Li Er-Shuan, to exile.”

“No!” The cry burst from Ami’s lips as she elbowed her way to the front of the crowd, ignoring the shouts and cries of indignation. “You can’t!” She tripped as she reached the platform, falling to her hands and knees before the cleric. “Please,” she said. “My father is unwell. He would not survive exile.”

“What is this?” the Right Hand said with disgust, backing away from her grasping hands.

“Please,” she said again, turning from the cleric to the Beast. “I am his daughter and I am telling you my father will not survive exile. If you must write the sentence, then let me carry it out in his stead.”

At the Beast’s feet, Li Er-Shuan moaned. His thick black-rimmed spectacles were cracked, and his threadbare tunic and trousers were tattered and torn. The Beast looked at Ami’s father, then looked at Ami. Although the expression on the boar-chimera mask was fierce and forbidding, she thought she sensed hesitation behind it. She dared not read it as kindness.

“If the criminal cannot survive exile,” they said at last, “then the sentence is tantamount to death.” They looked from Ami to her father and back again. “The law is clear: the punishment for trespassing is exile, not death. Therefore, we will not carry out the sentence.”

Ami collapsed to the platform in relief.

The Right Hand threw up their hands in exasperation. “Then what would you do with the criminal, O Compassionate One?”

The Beast turned to Ami. “What would you have me do?”