8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

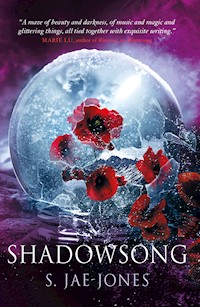

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

The conclusion to the gorgeous and lush Wintersong duology. "A maze of beauty and darkness, of music and magic and glittering things, all tied together with exquisite writing."―Marie Lu, #1 New York Times bestselling author on Wintersong. Six months after the end of Wintersong, Liesl is working toward furthering both her brother's and her own musical careers. Although she is determined to look forward and not behind, life in the world above is not as easy as Liesl had hoped. Her younger brother Josef is cold, distant, and withdrawn, while Liesl can't forget the austere young man she left beneath the earth, and the music he inspired in her. When troubling signs arise that the barrier between worlds is crumbling, Liesl must return to the Underground to unravel the mystery of life, death, and the Goblin King―who he was, who he is, and who he will be. What will it take to break the old laws once and for all? What is the true meaning of sacrifice when the fate of the world―or the ones Liesl loves―is in her hands?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from S. Jae-Jones and Titan Books

Title page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Part I

The Summons

The Price of Salt

The Mad, the Fearful, the Faithful

The Use of Running

A Maelstrom in the Blood

A Kingdom to Outrun

Interlude

Part II

Strange Proclivities

Faultlines

The House of Madmen and Dreamers

The Labyrinth

Sheep Skins

Der Erlkönig’s Own

The End of the World

Interlude

Part III

Snovin Hall

The Kinship Between Us

The Brave Maiden’s Tale, Reprise

The old Monastery

The Monster I Claim

Changeling

Intermezzo

Oblivion

He is for Der Erlkönig now

Brave Maiden’s End

Interlude

Part IV

The Return of the Goblin Queen

Inside Out

A Whole Heart and a World Entire

Finale

Coda

A Guide to Names and Titles

A Guide to German Phrases

A Guide to Musical Terms

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

SHADOWSONG

Also available from S. Jae-Jones and Titan Books

Wintersong

SHADOWSONG

S. JAE-JONES

TITANBOOKS

Shadowsong

Print edition ISBN: 9781785655463

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785655470

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: January 2018

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2018 by S. Jae-Jones. All rights reserved.

Hand-lettering and title page art courtesy of the author.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For the monstrous, and those who love us

AUTHOR’S NOTE

All books are mirrors of the author in some way or another, and Liesl’s journey to the Underground and back perhaps reveals more about me than I first realized. If Wintersong was my bright mirror, reflecting all my wish-fulfillment dreams about having my voice recognized and valued, then Shadowsong is my dark one, showing me how all the monstrous parts of the Underground were really another facet of me.

I would like to offer up a content note: Shadowsong contains characters who deal with self-harm, addiction, reckless behaviors, and suicidal ideation. If these subjects are triggering or otherwise upsetting to you, please proceed with caution. If you are struggling with suicidal thoughts, please know that there are resources and people who can assist you at the Samaritans, 116-123. Please call. You are not alone.

In many ways, Shadowsong is a far more personal work than its predecessor. I have been open and candid about writing Liesl as a person with bipolar disorder—much like her creator—but in Wintersong, I kept her diagnosis at arm’s length. Part of that is due to the fact that bipolar disorder as a diagnosis wasn’t really understood during the time in which she lived, and part of it is due to the fact that I did not want to face her—and therefore my—particular sort of madness.

Madness is a strange word. It encompasses any sort of behavior or thought pattern that deviates from the norm, not just mental illness. I, like Liesl, am a functioning member of society, but our mental illnesses make us mad. They make us arrogant, moody, selfish, and reckless. They make us destructive, to both ourselves and to those we love. We are not easy to love, Liesl and I, and I did not want to face that ugly truth.

And the truth is ugly. Liesl and Josef reflect both the manic and melancholic parts of myself, and they are dark, grotesque, messy, and painful. And while there are books that offer up prettier pictures, windows into a world in which things are healthy and whole, Shadowsong is not one of them. I kept the monster at bay in my first book; I would claim it as my own for my second.

Again I leave you with the phone number for the Samaritans, 116-123. There is no need to suffer alone. I see your monstrosity. I am not afraid. I have faced my own demons, but not alone. I had help.

116-123.

Remember me when I am gone away,

Gone far away into the silent land;

When you can no more hold me by the hand,

Nor I half turn to go yet turning stay.

Remember me when no more day by day

You tell me of our future that you plann’d:

Only remember me; you understand

It will be late to counsel then or pray.

Yet if you should forget me for a while

And afterwards remember, do not grieve:

For if the darkness and corruption leave

A vestige of the thoughts that once I had,

Better by far you should forget and smile

Than that you should remember and be sad.

– CHRISTINA ROSSETTI, Remember

To Franz Josef Johannes Gottlieb Vogler care of Master Antonius

Paris

My dearest Sepperl,

They say it rained on the day Mozart died.

God must see fit to cry on the days of musicians’ funerals, for it was pissing buckets when we laid Papa to rest in the church cemetery. The priest said his prayers over our father’s body with uncharacteristic swiftness, eager to get away from the wet and the muck and the sludge. The only other mourners aside from family were Papa’s associates from the tavern, there and gone when they realized no wake was to be held.

Where were you, mein Brüderchen? Where are you?

Our father left us quite a legacy, Sepp—of music, yes, but mostly of debt. Mother and I have been over our accounts again and again, trying to reconcile what we owe and what we can earn. We struggle to keep from drowning, to keep our heads above water while the inn slowly drags us down to oblivion. Our margins are tight, our purses even tighter.

At least we managed to scrape together enough to bury Papa in a proper plot on church grounds. At least Papa’s bones would be laid to rest alongside his forefathers, instead of being consigned to a pauper’s grave outside town. At least, at least, at least.

I wish you had been there, Sepp. You should have been there.

Why so silent?

Six months gone and no word from you. Do my letters reach you just one stop, one city, one day after you leave for your next performance on tour? Is that why you haven’t replied? Do you know that Papa is dead? That Käthe has broken off her engagement to Hans? That Constanze grows stranger and more eccentric by the day, that Mother—stoic, steadfast, unsentimental Mother—weeps when she thinks we cannot see? Or is your silence to punish me, for the months I spent unreachable and Underground?

My love, I am sorry. If I could write a thousand songs, a thousand words, I would tell you in each and every one how sorry I am that I broke my promise to you. We promised that distance wouldn’t make a difference to us. We promised we would write each other letters. We promised we would share our music with each other in paper, in ink, and in blood. I broke those promises. I can only hope you will forgive me. I have so much to share, Sepp. So much I want you to hear.

Please write soon. We miss you. Mother misses you, Käthe misses you, Constanze misses you, but it is I who miss you most of all.

Your ever-loving sister,

Composer of Der Erlkönig

To Franz Josef Johannes Gottlieb Vogler care of Master Antonius

Paris

Mein liebes Brüderchen,

Another death, another funeral, another wake. Frau Berchtold was found dead in her bed last week with frost about her lips and a silvery scar across her throat. Do you remember Frau Berchtold, Sepp? She used to scold us for corrupting the good, God-fearing children of the village with our terrifying tales of the Underground.

And now she is gone.

She was the third this month to pass in such a manner. We all grow fearful of the plague, but if it is plague, then it is like no pestilence we have ever known before. No pox, no bruises, no sign of the disease, none that we can see. The dead appear unharmed, untouched, save for the silver kisses about their mouth and neck. There is no rhyme or reason to their passing; they are old and young, male and female, healthy and infirm, sound and unsound altogether.

Is this why you do not write? Are you healthy, hale, whole? Are you even alive? Or will the next letter with your name upon it contain nothing but heartbreak and another funeral to arrange?

The elders of the town mutter dire portents under their breaths. “Elf-struck,” they say. “Goblin-marked. The devil’s handiwork. Mark our words: we are headed for trouble soon.”

Goblin-marked. Silver on the throat. Frost on the lips. I do not know what this betokens. I once believed that love was enough to keep the world turning. Enough to overcome the old laws. But I have witnessed the slow unraveling of reason and order in our boring, backward little village, the rejection of enlightened thought and a return to forgotten ways. Salt on every threshold, every entrance. Even the old rector has warded the steps of our church against evil, unbroken white lines that nevertheless blur the boundaries between what is sacred and what is superstition.

Constanze is no help. She isn’t much for conversation these days, not that our grandmother ever was. But in truth, she worries me. Constanze emerges from her quarters but seldom nowadays, and when she does, we are never certain which version of our grandmother we will meet. Sometimes she is present, sharp-eyed and as irascible as ever, but at others, she seems to be living in another year, another era altogether.

Käthe and I dutifully leave her a tray of food on the landing outside her room every evening, but every morning it remains untouched. A few bites may be taken of the bread and cheese, drops of milk scattered on the floor like fairy footsteps, but Constanze seems to take no sustenance beyond fear and her faith in Der Erlkönig.

Belief is not enough to live on.

There is madness in her bloodline, Mother would say. Mania and melancholy.

Madness.

Mother would say that our father drank to chase away his demons, to dull the maelstrom inside. His grandfather, Constanze’s father, drowned in it. Papa drowned in drink first. I hadn’t understood until I had demons of my own.

Sometimes, I fear there is a maelstrom swirling within me. Madness, mania, melancholy. Music, magic, memories. A vortex, spinning around a truth I do not want to admit. I do not sleep, for I fear the signs and wonders I see when I wake. Thorny vines wound round twigs, the clack of invisible black claws, blood blooming into the petals of a flower.

I wish you were here. You always could straighten my wandering, rambling thoughts and prune my wild imaginings into a beautiful garden. There is a shadow on my soul, Sepperl. It is not just the dead who are goblin-marked.

Help me, Sepp. Help me make sense of myself.

Yours always,

Composer of Der Erlkönig

To Franz Josef Johannes Gottlieb Vogler care of Master Antonius

Paris

Beloved,

The seasons turn, and still no word from you. Winter is gone, but the thaw is slow to come. The trees shiver in the wind, their branches still bare of any new growth. The air no longer smells of ice and slumber, but neither does the breeze bring with it any scent of damp and green.

I have not stepped foot in the Goblin Grove since summer and the klavier in your room has lain untouched since Papa died.

I don’t know what to tell you, mein Brüderchen. I have broken my promises to you twice over. The first by being unreachable, the second by failing to write. Not words, but melodies. Harmonies. Chords. The Wedding Night Sonata is unfinished, the last movement still unwritten. When the sun is high and the world is bright, I can find a myriad excuses for not composing in dusty corners, in accounting ledgers, in stores of flour, yeast, sugar, and butter, in the quotidian minutiae of running an inn.

But the answer is different in the dark. Between dusk and dawn, the hours when kobolds and Hödekin make mischief in the woods, there is only one reason.

The Goblin King.

I have not been honest with you, Sepp. I have not told you the whole story, thinking I would do so in person. This is not a story I thought I could commit to words, for words are insufficient. But I shall try anyway.

Once there was a little girl, who played her music for a little boy in the wood. She was an innkeeper’s daughter and he was the Lord of Mischief, but neither were wholly what they seemed, for nothing is as simple as a fairy tale.

For the span of one year, I was the Goblin King’s bride.

That is not a fairy tale, mein Brüderchen, but the unvarnished truth. Two winters ago, Der Erlkönig stole our sister away, and I journeyed Underground to find her.

I found myself instead.

Käthe knows. Käthe knows better than anyone just what it was like to be buried in the realm of the goblins. But our sister doesn’t understand what you would: that I wasn’t trapped in a prison of Der Erlkönig’s making, but became Goblin Queen of my own free will. She does not know that the monster who abducted her is the monster I claim. She thought I escaped the Goblin King’s clutches. She does not know he let me go.

He let me go.

In all our years of sitting at Constanze’s feet and listening to her stories, not once did she ever tell us what came after the goblins took you away. Not once did she ever say that the Underground and the world above are as close and as far as the other side of the mirror, each reflecting the other. A life for life. How a maiden must die in order to bring the land back from death. From winter to spring. She never told us.

But what our grandmother should have told us was that it isn’t life that keeps the world turning; it is love. I hold on to this love, for it is the promise that let me walk away from the Underground. From him. The Goblin King.

I do not know how the story ends.

Oh, Sepp. It is hard, so much harder than I thought to face each day as I am, alone and entire. I have not stepped in the Goblin Grove in an age because I cannot face my loneliness and remorse, because I refuse to condemn myself to a half-life of longing and regret. Any mention, any remembrance of those hours spent Underground with him, with my Goblin King, is agony. How can I go on when I am haunted by ghosts? I feel him, Sepp. I feel the Goblin King when I play, when I work on the Wedding Night Sonata. The touch of his hand upon my hair. The press of his lips against my cheek. The sound of his voice, whispering my name.

There is madness in our bloodline.

When I first sent you the pages from the Wedding Night Sonata, I thought you would read the through-line in the music and resolve the ideas. But I must own my own faults. I walked away, so it is up to me to write the end. Alone.

I want away. I want escape. I want a life lived to the fullest—filled with strawberries and chocolate torte and music. And acclaim. Acceptance. I cannot find that here.

So I look to you, Sepp. Only you would understand. I pray you will understand. Do not leave me to face this darkness alone.

Please write. Please.

Please.

Yours in music and madness,

Composer of Der Erlkönig

To Maria Elisabeth Ingeborg Vogler

Master Antonius is dead. I am in Vienna. Come quickly.

EVER THINE

I can only live, either altogether with you or not at all.

—LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN, the Immortal Beloved letters

THE SUMMONS

“absolutely not,” Constanze said, thumping the floor with her cane. “I forbid it!”

We were all gathered in the kitchens after supper. Mother was washing up after the guests while Käthe threw together a quick meal of spätzle and fried onions for the rest of us. Josef’s letter lay open and face up on the table, the source of my salvation and my grandmother’s strife.

Master Antonius is dead. I am in Vienna. Come quickly.

Come quickly. My brother’s words lay stark and simple on the page, but neither Constanze nor I could agree upon their meaning. I believed it was a summons. My grandmother believed otherwise.

“Forbid what?” I retorted. “Replying to Josef?”

“Indulging your brother in this nonsense!” Constanze pointed an accusing, emphatic finger at the letter on the table between us before sweeping her arm in a wild, vague gesture toward the dark outside, the unknown beyond our doorstep. “This . . . this musical folly!”

“Nonsense?” Mother asked sharply, pausing in scrubbing out the pots and pans. “What nonsense, Constanze? His career, you mean?”

Last year, my brother left behind the world he had known to follow his dreams—our dreams—of becoming a world-class violinist. While running the inn had been our family’s bread and butter for generations, music had ever and always been our manna. Papa was once a court musician in Salzburg, where he met Mother, who was then a singer in a troupe. But that had been before Papa’s profligate and prodigal ways chased him back to the backwoods of Bavaria. Josef was the best and brightest of us, the most educated, the most disciplined, the most talented, and he had done what the rest of us had not or could not: he had escaped.

“None of your business,” Constanze snapped at her daughter-in-law. “Keep that sharp, shrewish nose out of matters about which you know nothing.”

“It is too my business.” Mother’s nostrils flared. Cool, calm, and collected had ever been her way, but our grandmother knew how best to get under her skin. “Josef is my son.”

“He is Der Erlkönig’s own,” Constanze muttered, her dark eyes alight with feverish faith. “And none of yours.”

Mother rolled her eyes and resumed the washing up. “Enough with the goblins and gobbledygook, you old hag. Josef is too old for fairy tales and hokum.”

“Tell that to that one!” Constanze leveled her gnarled finger at me, and I felt the force of her fervor like a bolt to the chest. “She believes. She knows. She carries the imprint of the Goblin King’s touch upon her soul.”

A frisson of unease skittered up my spine, icy fingertips skimming my skin. I said nothing, but felt Käthe’s curious glance upon my face. Once she might have scoffed along with Mother at our grandmother’s superstitious babble, but my sister was changed.

I was changed.

“We must think of Josef’s future,” I said quietly. “What he needs.”

But what did my brother need? The post had only just come the day before, but already I had read his reply into thinness, the letter turned fragile with my unasked and unanswered questions. Come quickly. What did he mean? To join him? How? Why?

“What Josef needs,” Constanze said, “is to come home.”

“And just what is there for my son to come home to?” Mother asked, angrily attacking old rust stains on a dented pot.

Käthe and I exchanged glances, but kept our hands busy and our mouths shut.

“Nothing, that’s what,” she continued bitterly. “Nothing but a long, slow trek to the poorhouse.” She set down the scrubbing brush with a sudden clang, pinching the bridge of her nose with a soapy hand. The furrow between her brows had come and gone, come and gone ever since Papa’s death, digging in deeper and deeper with each passing day.

“And leave Josef to fend for himself?” I asked. “What is he going to do so far away and without friends?”

Mother bit her lip. “What would you have us do?”

I had no answer. We did not have the funds to either send ourselves or to bring him home.

She shook her head. “No,” she said decisively. “It’s better that Josef stay in Vienna. Try his luck and make his mark on the world as God intended.”

“It doesn’t matter what God intends,” Constanze said darkly, “but what the old laws demand. Cheat them of their sacrifice, and we all pay the price. The Hunt comes, and brings with them death, doom, and destruction.”

A sudden hiss of pain. I looked up in alarm to see Käthe suck at her knuckles where she had accidentally cut herself with the knife. She quickly resumed cooking dinner, but her hands trembled as she sliced wet dough for noodles. I rose to my feet and took over making spätzle from my sister as she gratefully moved to frying the onions.

Mother made a disgusted noise. “Not this again.” She and Constanze had been at each other’s throats for as long as I could remember, the sound of their bickering as familiar as the sound of Josef practicing his scales. Not even Papa had been able to make peace between them, for he always deferred to his mother even as he preferred to side with his wife. “If I weren’t already certain of your comfortable perch in Hell, thou haranguing harpy, I would pray for your eternal soul.”

Constanze banged her hand on the table, making the letter—and the rest of us—jump. “Can’t you see it is Josef’s soul I am trying to save?” she shouted, spittle flying from her lips.

We were taken aback. Despite her irritable and irascible nature, Constanze rarely lost her temper. She was, in her own way, as consistent and reliable as a metronome, ticking back and forth between contempt and disdain. Our grandmother was fearsome, not fearful.

Then my brother’s voice returned to me. I was born here. I was meant to die here.

I sloppily dumped the noodles into the pot, splashing myself with scalding hot water. Unbidden, the image of coal black eyes in a sharp-featured face rose up from the depths of memory.

“Girl,” Constanze rasped, fixing her dark eyes on me. “You know what he is.”

I said nothing. The burble of boiling water and the sizzle of sautéing onions were the only sounds in the kitchen as Käthe and I finished cooking.

“What?” Mother asked. “What do you mean?”

Käthe glanced at me sidelong, but I merely strained the spätzle and tossed the noodles into the skillet with the onions.

“What on earth are you talking about?” Mother demanded. She turned to me. “Liesl?”

I beckoned to Käthe to bring me the plates and began serving supper.

“Well?” Constanze smirked. “What say you, girlie?”

You know what he is.

I thought of the careless wishes I had made into the dark as a child—for beauty, for validation, for praise—but none had been as fervent or as desperate as the one I had made when I heard my brother crying feebly into the night. Käthe, Josef, and I had all been stricken with scarlatina when we were young. Käthe and I were small children, but Josef had been but a baby. The worst had passed for my sister and me, but my brother emerged from the illness a different child.

A changeling.

“I know exactly who my brother is,” I said in a low voice, more to myself than to my grandmother. I set a dish heaped high with noodles and onions in front of her. “Eat up.”

“Then you know why it is Josef must return,” Constanze said. “Why he must come home and live.”

We all come back in the end.

A changeling could not wander far from the Underground, lest they wither and fade. My brother could not live beyond the reach of Der Erlkönig, save by the power of love. My love. It was what kept him free.

Then I remembered the feel of spindly fingers crawling over my skin like bramble branches, a face wrought of hands, and a thousand hissing voices whispering, Your love is a cage, mortal.

I looked to the letter on the table. Come quickly.

“Are you going to eat your supper?” I asked, glancing pointedly at Constanze’s full plate.

She gave her food a haughty look and sniffed. “I’m not hungry.”

“Well, you’re not getting anything else, you ungrateful nag.” Mother angrily stabbed at her supper with her fork. “We can’t afford to cater to your particular tastes. We can barely afford to feed ourselves as it is.”

Her words dropped with a thud in the middle of our dinner. Chastened, Constanze picked up her fork and began eating, chewing around that depressing pronouncement. Although we had settled all of Papa’s debts after he died, for every bill we paid, yet another sprung up in its place, leaks on a sinking ship.

Once we were finished with supper, Käthe cleared the plates while I began the washing up.

“Come,” Mother said, extending her arm to Constanze. “Let’s get you to bed.”

“No, not you,” my grandmother said with disgust. “You’re useless, you are. The girl can help me upstairs.”

“The girl has a name,” I said, not looking at her.

“Was I talking to you, Elisabeth?” Constanze snapped.

Startled, I lifted my head from the dishes to see my grandmother glaring at Käthe.

“Me?” my sister asked, surprised.

“Yes, you, Magda,” Constanze said irritably. “Who else?”

Magda? I looked at Käthe, then at Mother, who seemed as bewildered as the rest of us. Go, she mouthed to my sister. Käthe made a face, but offered her arm to our grandmother, wincing as Constanze gripped it with all her spiteful strength.

“I swear,” Mother said softly, watching the two of them disappear up the stairs together. “She grows madder by the day.”

I returned to washing the dishes. “She’s old,” I said. “It’s to be expected, perhaps.”

Mother snorted. “My grandmother remained sharp until the day she died, and she was older than Constanze by an age.”

I said nothing, dunking the plates in a clean tub of water before handing them to Mother to dry.

“Best not indulge her,” she said, more to herself than to me. “Elves. Wild Hunt. The end of the world. One might almost think she actually believes these fairy stories.”

Finding a clean corner of my apron, I picked up a plate and joined Mother in drying the dishes. “She’s old,” I said again. “Those superstitions have been around these parts forever.”

“Yes, but they’re just stories,” she said impatiently. “No one believes them to be true. Sometimes I’m not sure if Constanze knows whether we live in reality or a fairy tale of her own making.”

I said nothing. Mother and I finished drying the dishes and put them away, wiped down the counters and tabletops, and swept up what little dirt there was on the kitchen floor before making our separate ways toward our rooms.

Despite what Mother believed, we were not living in a fairy tale of Constanze’s own making, but a terrible, terrible reality. A reality of sacrifices and bargains, goblins and Lorelei, of myth and magic and the Underground. I who had grown up with my grandmother’s stories, I who had been the Goblin King’s bride and walked away knew better than anyone the consequences of crossing the old laws that governed life and death. What was real and what was false was as unreliable as memory, and I lived in the in-between spaces, between the pretty lie and the ugly truth. But I did not speak of it. Could not speak of it.

For if Constanze was going mad, then so was I.

the boy’s playing was magic, it was said, and those of discerning taste and even deeper pockets lined up outside the concert hall for a journey into the realms of the unknown. The venue was small and intimate, seating but twenty or so, but it was the largest gathering for which the boy and his companion had ever played, and he was nervous.

His master was a famous violinist, an Italian genius, but age and rheumatism had long since twisted the old man’s fingers into stillness. In the maestro’s prime, it was said Giovanni Antonius Rossi could make the angels weep and the devil dance with his playing, and the concertgoers hoped that even a glimmer of the old virtuoso’s gifts could be heard in his mysterious young pupil.

A foundling, a changeling, the concertgoers whispered. Discovered playing on the side of the road in the backwoods of Bavaria.