Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

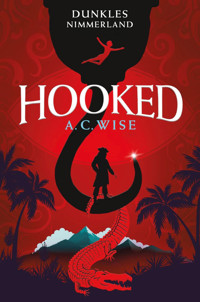

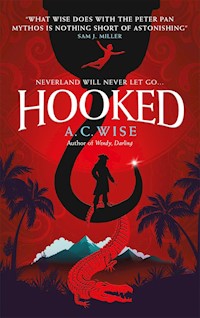

A dark, gorgeous reimagining about what happened to Captain Hook after Neverland from the bestselling author of Wendy, Darling – filled with eerie suspense and heart-breaking anguish Once invited, always welcome. Once invited, never free. Captain James Hook, the immortal pirate of Neverland, has died a thousand times. Drowned, stabbed by Peter Pan's sword, eaten by the beast swimming below the depths, yet James was resurrected every time by one boy's dark imagination. Until he found a door in the sky, an escape. And he took the chance no matter the cost. Now in London twenty-two years later, Peter Pan's monster has found Captain Hook again, intent on revenge. But a chance encounter leads James to another survivor of Neverland. Wendy Darling, now a grown woman, is the only one who knows how dark a shadow Neverland casts, no matter how far you run. To vanquish Pan's monster once and for all, Hook must play the villain one last time… Exploring themes of grief, survivor's guilt and healing broken bonds, Hooked is a modern-day Peter Pan story, perfect for fans of retellings, Christina Henry and V.E. Schwab.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 469

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by A.C. Wise

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

1A Taste of the Poppy

2Empty

3Reunions

4The Immortal Captain

5Between Two Worlds

6Echoes

7Old Enemies, New Allies

8The Black Blade

9The Hunting Beast

10Home

11A Hole in the Stars

12A Body Remembers

13A City of Rain

14Christmas Day

15The Hollow Boy

16Lost Girl

17The Burning Sky

18Lost Boys

19How Sweet the Bloom

20Chasing Ghosts

21Neither Pirate, Nor Gentleman

22The Black Blade Returned

23The Last Pirate in Neverland

24A Captain Goes Down with his Ship

25Burials

26New Year’s Day

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by A.C. Wise

Wendy, Darling

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Hooked

Print edition ISBN: 9781789096835

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789096842

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition July 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2022 A.C. Wise. All rights reserved.

A.C. Wise asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

A TASTE OF THE POPPY

LONDON – 1939

The wave curls above him, poised, laden with panic.

He remembers drowning.

Limbs weighted and wanting to drag him down, lungs screaming with the thwarted desire to expand, mouth poised to open traitorously and let in water instead of air.

James gropes for the table beside him, for the pipe, but the smoke is already in his lungs. He remembers to breathe out. His lungs stop screaming when he does. The smoke coils in the air above him, hanging there a moment, teasing the outline of a shape, but when he looks again, it dissipates.

Hunger gnaws at him and he pulls in another lungful. As he does, James feels himself doubled, a ghost rising from his skin to move about the flat. Slipped out of time, he feels himself once again taking the actions he took moments ago—his hand shaking with need, guts cramping, sweat slicking his skin. He hears the wooden box rattle, the scant amount of opium inside dwindling every day.

A dizzying sensation as he watches himself, feels himself, rolling tar into a sticky ball, pulling it into long strands, filling his pipe. He feels smoke in his lungs. Only a small slip this time, minutes not hours or years, but still, it is disorienting. And it has been happening more and more frequently, his unmooring from time. His guts cramp again, the urge to vomit, and in the next moment, he slams back into his body where he lies on the chaise, gasping for air.

He remembers drowning.

The drug should blunt the effect, stave off the memory of the deaths he suffered again and again at the hands of a mere child, a boy. It used to, but now it only makes the sensation worse, stretching him thin between two worlds, this one and…

James refuses the name. He’s not there; he is here, in London. Home.

But what manner of home is it without…

He glances to the wooden box beside him. What will he do when the opium is gone? He’s an old man, feeling his age now as he never did before. His fingers, once quick-slipping into pockets to relieve them of their bills, once quick with a blade as well, have slowed. What skill does he left to live by?

He lets himself lie back, a rough chuckle taking him and turning into a cough. If he were any other man, he would fear. It would be a race to see what would take him first—starvation, withdrawal, or madness. But he’s always been too stubborn to die, too determined. Weary as he is, above all, he knows he will survive.

James lifts the pipe again, using his flesh and blood hand. The other, wood, gleaming warm in the light and chased in silver, rests in his lap. The delicate, articulated joints that allow him to bend or straighten the fingers when he can be bothered to remember curl slightly now, as if cupping something gently in his palm, but his hand is empty. He draws breath and holds it.

“You promised me you’d be careful. Your dreams are dangerous things, James.”

The voice is a knife, and James whips around. Another fit of coughing leaves his eyes streaming. Through the blur he sees Samuel standing in the corner, hands folded neatly in front of him, expression mixing admonishment and sorrow.

James forgets how to breathe entirely. He forgets the ache in his leg and the fact that when he walks now, he needs a cane to steady him. He’s halfway to rising, going to Samuel, when a twinge in his thigh brings him crashing to one knee beside the chaise. Pain spikes from the point of impact and catches as a gasp in his throat. And still, he almost crawls to the surgeon on hands and knees, a pitiful thing, ready to bury his face in the hem of Samuel’s coat.

But James forces himself to straighten.

“Fuck off.” The words come out smoke-roughened, harsh with emotion and the effort to speak with conviction. “You’re not real.”

It’s unkind, but then so is Samuel’s ghost.

“I don’t want you here.” James tries to curl his lips into their old sneer.

He pulls the memory of striding the deck in a swirl of blood-red coat, men trembling before him, around him like armor. He must be that, not this pathetic creature, brought low with need. Samuel isn’t in the room with him; Samuel has been dead for fifteen years.

Yet the grief hasn’t lessened. Always the wave of it is there, ready to swamp him if James lets his concentration falter for even a moment. If he lets his guard down, time comes unstuck and the pain is just as fresh as it ever was—worse than dying, worse than every time he’s drowned.

The specter in the corner refuses to waver. Samuel’s eyes were never the blue-gray shade fixing James balefully now. Nor was his skin the color of seawater, and just as translucent. James can see straight through him to the wall.

Samuel isn’t real. He isn’t here. And knowing as much does nothing to lessen James’s wanting, the hurt undoing him, unraveling him and leaving him flayed.

“Leave me alone in my misery why don’t you?” He snaps the words, angling his body away so he won’t have to see whether Samuel obediently fades.

But he feels it. A tsk, a disappointed sound pinging directly against the delicate bones of his ear. A sigh of displaced air, and then Samuel is gone. Just like all the other pirates, leaving James alone, the only one.

The sense of loss is immediate. But instead of scrambling to the corner to plead with empty air, he presses down on the feeling of absence like a bruise and lets it ground him. The ache in his chest eases, if only for a moment.

He braces one arm and levers himself up, muscles trembling with the effort. There’s a cold pulse of complaint from his thigh where the shards of something that may or may not be metal buried themselves long ago. But his leg holds when he stands, and James retrieves his cane where it leans against the back of the chaise.

He runs his gaze across the shelves crammed with books—of which he has not read a single one—along the wall, and up to the window that peers like an eye out over London, to the bed, far too large for one man alone, to the stove, the kettle, the wardrobe, his coat hung by the door. Last, as always, his gaze comes to rest on the skull sitting on the bedside table.

James moves slowly, limping to the bed. He ignores the grinding pain from his knee where it struck the floor and the steady ache in his thigh as he sits. His hand—the flesh and blood one—touches down atop the skull. The whorls of his fingertips meet the whorls carved into the bone. The pattern chased in silver is the same design covering his other hand, the wooden one. He’d found a scrimshaw artist to do the work, and though the man had balked when presented with a human skull, James’s money was good enough in the end.

As he pulls the skull onto his lap, his heartbeat finally calms, his breathing steadies. He is here and now, in London. His name is James, not Hook. And he is no one’s captain.

And yet… It is nothing to summon the feel of the deck rolling beneath his feet, the creak and sigh of the ropes and the snap of sails. Neverland—he admits to the name at last; it is always there, and Hook is always there, just beneath the surface. At times, he never left, never fled and fell through the world.

That’s what Samuel never understood, what James could never explain. Samuel had warned him that his dreams were dangerous—that the smoke trance he put himself into in place of actual dreaming would act as a beacon, drawing Neverland’s eye. But without the drug, James remembers too much. He drinks, he smokes, to dull that other self, to keep Hook and Neverland from rising again.

He did it, always, to keep them safe.

Empty sockets gaze up from under ridges of bone, as reproachful as Samuel’s ghost. James replaces the skull on the table, turns it slightly so it looks away. For years, he resisted the pull to keep them safe, to keep Samuel safe, but who is there left to protect now? What does it matter if he’s reckless with his own life?

Neverland creeping steadily closer, pressed against the skin of this world, hungering, wanting what it’s been denied all these years—James,Hook—as its last meal.

Why should he deny it?

And another thought rises, a sliver of sick hope he shouldn’t dare, and yet cannot help. What if some remnant of Samuel waits for him in that other world? Yes, he swore to Samuel, but what does a promise mean to a dead man?

It’s been fifteen years, and the pain hasn’t grown less, contrary to popular logic. All the while, James kept holding on, promising himself that time would heal him if he could only be patient. But if anything, the hurt has grown worse. As if all this time, the way between worlds has only grown thinner, his memories sharper than the life he lives now, leaving the loss fresher, the wound opened wider rather than scabbed over or scarred. Neverland has always been a beast snapping at his heels; now he can almost feel it, and he’s tired of running.

He’d kept his promise, determined to honor Samuel’s memory, and yet Samuel’s ghost haunts him, pitiless. If keeping his promise brings no relief, what is the point of it? More and more, he finds himself unanchored in time. Now, or then—what does it matter? He is old, he is tired. Hasn’t he at last earned the right to rest, to stop fighting against temptation?

James pushes himself up again and returns to the chaise. He draws in another lungful of smoke, and lets himself drift. Lets himself think deliberately of Neverland. After so long, after years of bearing up under the weight of grief alone. He lets himself go.

And almost immediately, waves rock him. He feels the lift and fall of the deck, the peak and trough. The air is salt-crystal—denseenough to crack between his teeth. He is hale and hearty, in a coat the color of blood, armed with a wicked blade.

The ceiling of his flat blurs into a sky smeary with clouds over a scattering of stars. He closes his eyes as he leans back against the chaise. Or perhaps they remain open. It doesn’t matter. Waking or sleeping, eyes open or closed, he would still see Neverland. It’s been drawing closer all this time, and he no longer has the will to resist it. Among the stars is a place where the sky grows thinnest, framed in sharp-edged silver light.

A door.

It’s a thing he’s sensed before and never allowed himself to look at fully, but now he turns his attention to it and lets himself see. James lets himself feel the weight of that other world and everything it contains—his ship and his pirates and Pan—all leaning against the imagined door in the sky. Imagined, but also real. Because of course in a world made for a child all ego and desire, wanting would be a door, a literal door. Why shouldn’t James avail himself of it too?

Reckless, yes, and ill-advised, but he doesn’t care. As he once threw himself wildly into the teeth of a storm, James draws one more breath of smoke and throws all his will and wanting against that door, reaching back for a world he swore he’d never reach for again.

There’s a sensation like lightning striking, electricity jumping the gap and snapping through his bones. A rush of displaced air, and on the other side of nowhere, something grabs ahold of his reaching hand.

Breath leaves him in a startled gasp. When the coil of smoke hangs in the air this time it doesn’t just tease a shape, it twists slowly, gathering mass, solidity.

Scales and wide-open jaws. The beast rolls in the air above him, lazy and mocking. His chest compresses beneath fathoms of seawater gone the color of blood-dark wine. Fear all at once rushing back when he’d thought himself immune.

Pan’s hunting beast. In Neverland, he’d felt it always, moving beneath the world’s skin. He’d been aware of it wherever on the island it was, just as it was always aware of him. But he’d come to London, he’d escaped.

Yet now all the beast has to do is turn its eyes like rotten coins upon him and it will know him.

Your dreams are dangerous, James.

Panic freezes James upon the chaise. The old desire to live, almost despite himself, pumps through his veins with an almost painful intensity. He does not want to die, not again. A prelude to a death roll, the beast makes another turn, seeking. Starlight glints from it like light striking a blade. Jaws open, the beast plunges down.

James ducks, throwing an arm up in a vain attempt to ward off the teeth. The motion sends him crashing to the ground, knocking the table over, his pipe and matches and the wooden box scattering. The beast sails overhead, missing him. James presses himself flat, rolling beneath the chaise. The beast whips around, a frustrated motion, its jaws snapping at nothing.

It circles once, and again, searching. James forgets terror for a moment—can’t the beast feel him? Can’t it see him? But if he closed his eyes, would he know where the beast was in the room? No. It’s like a sense has been removed from him, one he’d almost forgotten. He can’t feel the creature as he once could, the dreadful awareness of it always clinging to him wherever he was. It seems the beast cannot feel him either. James remains where he is, flat beneath the chaise, waiting, but the pounding of adrenaline in him fades. There must be something else wrong with the creature. It is reduced from its former terror, its former glory, broken. Much like James himself.

The beast turns once more, churning the air, sailing farther away from him and toward the window, blundering like a creature lost. James holds his breath a moment longer; when he dares to poke his head from beneath the chaise, the beast is gone.

His pulse stutters. James blinks at the room, expecting for a moment that it will become the room at the prow of a ship, with a narrow bed hung in rich brocade. But it is only his room, his flat in London. There is no beast.

Perhaps there never was. Perhaps he imagined the whole thing. Another moment slipped out of time. The door, only another illusion, born in smoke and wanting.

Reflex draws his gaze to the corner, hoping for Samuel’s ghost, but the space remains stubbornly empty. It hurts more than it should.

James forces himself up one more time, leaving the fallen table and scattered pipe as he makes his way to the eye-shaped window overlooking London. His whole body feels bruised, as much his age as the fall. He lets the cane take his weight. A starless sky stretches over the city. From here, he can see the rooftops of the neighboring buildings. Nothing looks amiss, yet he feels something out of place, something that doesn’t belong.

A brass scope sits atop the bookshelf below the window, a gift from Samuel, an old joke, as if this flat perched above the city were a crow’s nest. James puts the glass to his eye. He scans the forest of chimneys, the dense world of brick.

For just a moment, he imagines a sinuous shape moving between them, the flick of a tail disappearing from sight. But is that only because he wants to see it? If the beast is real, and remains, perhaps Samuel does too. His breath catches, but when he looks again, there is only the London sky and the city below him.

Perhaps he should be relieved. Samuel is—was—right. Neverland was a terrible place; they escaped it, and it’s better left behind for good. He dared too close to the edge tonight, and perhaps his desire did finally crack that door wide. And perhaps something slithered through. A monster. A shadow. A thing of scales and jaws twisting through the night. It snapped once and missed, but will it circle around again as it always has, time and time before? He wishes he could dismiss it as illusion, an effect of the drug, but he fears he has done what Samuel always warned him again and drawn Neverland’s attention.

And now the creature is out there. Searching for him. Hunting.

EMPTY

LONDON – 1939

The scent of fresh-baked sweet rolls, glazed in marmalade, wafts from the folded-over paper bag balanced atop the mountain of parcels in Jane’s arms. It’s maddening, taunting her as she winds through the slushy London streets, cold nipping at her cheeks, wind tugging her coat hem. It took all her willpower not to tear into the bag the moment she made her purchase, but she promised herself she’d save them to share them with Peg.

The sweet rolls, a mutual favorite, are just one part of the celebration they have planned tonight for surviving their first term at the Royal College. Tomorrow they’ll both go their separate ways, home for the holidays, and Jane already feels a pang at the thought. She’s never met someone she liked as instantly, or got along with as well as Peg. Even though it’s only a short break before classes start again, Jane will miss her.

She and Peg met on their very first day at the college, and although Peg ultimately switched out of the medical program into the pharmaceutical program, they’ve still been together every single day since that first, deciding to become flatmates only a week after they’d met. They’d bonded almost instantly over being the only two female students in the room in their first anatomy class. And they’d quickly discovered that unlike the young men in their classes, they had to work twice as hard to prove they deserved their place there. They’d sworn then and there to always have each other’s backs, to support each other, and to not let each other quit, no matter how bad things got.

Jane can’t imagine giving up on her dream of becoming a doctor, but there are times when simply getting through a day is exhausting. But knowing Peg is going through the same thing makes it so much easier to bear. Lately there have been rumors that the Royal College is trying to block women from sitting medical exams again. With the war, Jane would think more doctors would be wanted, not fewer, but apparently while dying of sepsis from a treatable wound would be a terrible fate, for some the idea of letting a “lady doctor” do the treating is simply a bridge too far.

As their building comes into sight, Jane pushes the bitter thought down. While she was grateful for her heavy wool coat outside, by the time she climbs the stairs to their door, she’s sweating. She manages to get the door unlocked without dropping any packages, and steps inside.

“Is the kettle on?” Jane sets her packages on the table, unwinding her scarf and freeing herself from her coat.

Peg doesn’t answer. More likely than not, she’s lost in one of her mystery novels. It never ceases to amaze Jane how Peg can read the same book several times over and still get as much enjoyment out of it the third time as the first.

“What’s the point after you know who the murderer is?” she’d asked once.

“That’s the best part!” Peg had answered her with a grin. “The second time around you get to go back and see all the clever clues the author put in that you missed the first time.”

“What about the third time?”

But Peg had only stuck her tongue out. Last Jane checked, Peg was working her way through all of Agatha Christie’s Poirot novels again. How she finds time on top of her schoolwork, not to mention spending time with Simon, Jane will never know.

“Peg?” She hangs her coat and scarf from the hook by the door, shaking the last drops of melted snow from her bobbed hair.

Surely Peg must have heard her come in by now. Unless she’s with Simon, the two of them holed up in a tea shop somewhere, lost in each other and oblivious to the weather outside. The thought makes Jane smile. She’d met Simon early on too, one of the handful of decent male students who’d never questioned Jane’s right to be in the program. She’d been the one to introduce Peg and Simon. Simon had been so painfully shy that Jane never would have imagined a relationship blossoming—not that she’d been trying to set them up—but they’d hit it off, Peg balancing Simon’s blushing and tongue-tied speech with openness and enthusiasm.

“Peg?” Jane plucks the pastry bag from the top of her stack of parcels. She sets the kettle on to boil in the flat’s tiny kitchen and leaves it heating to knock on Peg’s door.

The door swings inward. Jane is about to wave the pastry bag in front of the gap, wafting the scent into Peg’s room, but she stops.

Absence breathes out from the open door, making all the hairs on the back of Jane’s neck stand on end. There’s a kind of missingness that goes far deeper than Peg simply not being there.

Jane pushes the door open all the way.

The pastry bag drops from her hand. Peg lies sprawled across her narrow bed, sheets rumpled beneath her. She is there, Jane can clearly see her, and she is not. Jane’s gaze slides away from her flatmate, her friend, and Jane has to force herself to look at Peg, to see her. It’s not squeamishness. It’s as if Peg no longer belongs in the world and so the world is trying to erase her.

Jane’s stomach churns with the utter wrongness. She’s watched her professors peel back skin to reveal different muscle groups, crack ribcages to show all the organs lined up inside, saw bones into neat cross-sections to reveal the marrow inside, but this is something else altogether. Jane knows how a human body is meant to work, all the things that make it move and breathe, and what happens when those processes stop. This is not that. Even though she can plainly see Peg, it’s as though something fully snipped her from existence, leaving a Peg-shaped hole behind.

Jane forces herself to step farther into the room even though a thickness in the air tries to resist her. She touches the pulse-points at Peg’s wrist and below her jaw, even knowing what she will find. She draws her fingers away from the waxen coolness of Peg’s skin as quickly as she can. There’s an extra pallor to Peg’s flesh, as though she’s already been drained of every last drop of her blood, but the sheets beneath her remain pristine, the walls unmarred. There’s no sign of violence, no marks on her skin, no evidence of a struggle.

A strand of Peg’s dark hair lies across her cheek, almost touching the corner of her mouth, which is open as though she died in the act of taking a breath, or was about to say a word. Her eyes stare, and even this Jane must struggle to see because Peg’s features want to blur, rearrange themselves, refuse her gaze.

Did someone break in? Jane knows for certain she unlocked the door when she entered, and she certainly would have noticed if it had been forced. She glances around the room; it’s a horrible relief in a way she doesn’t want to admit, looking away from her friend’s lifeless body. The window is open a fraction. Wind slips through, biting cold. But it’s not enough of a gap for someone to get inside.

Unless whatever killed Peg isn’t human.

The thought drops, unwelcome, like a stone in Jane’s mind and sits there. Her thoughts are dull, sluggish, trying to move around it. She stares at the window, the gap, with a sense there’s something she’s forgotten. She should close the window; Peg will freeze when she returns. Then Jane remembers. She turns back to the thing on the bed, a choked sob rising in her throat.

It’s not as though she forgot—how could she forget? Except when she looks away, she does. Peg slides from her mind, because the thing on the bed isn’t Peg. It’s the absence of Peg. Peg has been utterly undone. Shaking, Jane puts a hand to her mouth. They’d promised to stick together, to have each other’s backs. They were supposed to protect each other, and Jane has utterly failed.

She keeps her eyes on Peg even as she bends mechanically to pick up the dropped pastry bag. She steps backward out the door, holding Peg in her sight as long as she can and fixing her in her mind so she doesn’t slip away again. In the kitchen, Jane finds the kettle nearly boiled dry and lifts it automatically from the heat, turning off the burner. She should call the police. There’s a telephone in the downstairs hall, but at the moment it feels impossibly far away. Jane’s body is heavy and all at once, all she wants to do is sleep.

Police. Scotland Yard. She will call. Eventually. She will. But right now, more than anything in the world, the only person she wants to talk to—despite everything between them, the broken promises and the lies, despite the wound that has been eight years healing and only managed to scab—the only person she can fathom talking to at all is her mother.

REUNIONS

Wendy lifts her muffler, covering half her face and leaving only her eyes visible. Beneath her coat, her skin prickles, first hot, then cold, a sense of unease dogging her heels as sure as the December wind. She had no intention of coming into the city today. There’s more than enough to do getting the house ready with Jane coming home for the holidays, her brother Michael coming for Christmas, and her other brother John and his wife and daughter coming for New Year’s Day. But something is wrong. There is something here that doesn’t belong.

Wendy had felt it all at once last night, sitting in the parlor before the fire and putting the finishing touches on a skirt she’d sewed to give Jane for Christmas. It was as though a door had opened somewhere far off, and at the same time very close by, and something cold and dark had come rushing through. She’d stood up so suddenly that the fabric had spilled from her lap, the thread unwinding all the way across the floor so that the spool had nearly ended up in the fire.

Neverland.

The name had risen to her tongue, but she’d clamped it tight behind her teeth, refusing to speak it out loud. Still, she hadn’t been able to stop herself from rushing to the window, peering out, looking for a subtle shift in the stars. The night had been brutally cold, brutally clear—no clouds to block the moon or her view of the sky. The only thing she’d seen was the dark, speckled in silver light, nothing amiss, nothing out of place.

No door opening in the sky. No boy who wasn’t a boy come to take her hand and ask her to fly away. Her heart had surged, a complicated mix of hope and fear, and then come crashing down again as she’d stood at the glass, her breath fogging against it, looking and hoping and seeing nothing.

Neverland had given her so much as a child. And it had taken more than she’d realized. Eight years ago, it had taken her daughter, and Wendy had stolen her back, bringing Neverland crashing down around them as they’d escaped home again.

So why had it felt as though the way between worlds had opened again, however briefly? She’d tried to convince herself that it must have been her imagination, she couldn’t have felt what she’d thought she’d felt. But after reclaiming the fallen skirt and trying to resume her work, she’d found herself unable to sew, her fingers grown clumsy, almost shaking. She’d been unable to concentrate, and later that night, unable to sleep. She’d paced her room half the night, and almost the second it was decently light—despite the storm growing across the sky—she’d taken herself to the station and bought a train ticket into London.

The sense is even stronger now as she dodges last-minute shoppers and puddles of slush. Between the thick-falling snow, the air feels rife with ghosts. Something she can almost see, almost feel, something out of place. If she could only find it.

And then—there. It’s as though someone has tugged on a rope tied to her spine. Wendy stops in her tracks like a stone planted in the midst of a river, drawing angry murmurs from the crowd forced to part and flow around her. She ignores them, twisting around to look behind her. But there’s only a sea of faces, indistinct in the gray and wrapped against the cold. There’s nothing to make her feel once again as though a door opened, as though someone on the far side of it called her name.

Perhaps she’s being foolish. Her life has been quiet of late, content and cozy in a way she’d never imagined it could be. At times, though, it feels too quiet, almost stifling. There are times when the urge takes her to simply get on a train without a true destination in mind, or get on a boat and sail as far as she can. As a young girl, she never imagined life as a married woman, as a mother, living in one place and never going off on grand adventures. Last night had she simply let boredom get the better of her, wishing for something, a mystery or an adventure—even a terrible one—to come sweep her away again?

Guilt comes with the thought and Wendy plunges back into the crowd, lowering her head. She’s barely taken two steps when the tug comes again, sharper this time. At almost the same moment, a hand touches her shoulder. Wendy lets out a startled yelp, muffled by the wool across her mouth. She spins, instinct raising her hand to strike whoever has ahold of her. The man ducks, raising an arm against her blow and Wendy catches herself. Stunned, she lets her hand drop, staring.

The hand raised to ward off her blow is made of wood, a warm red-brown that strikes to the heart of her, and she knows instinctively that it doesn’t belong to this world. Elaborate patterns like curls of smoke flow across its surface—silver gleaming dully despite the gray sky. Where the wooden finger joints bend slightly, delicate rods and pins are just barely visible, so finely crafted that for a moment she almost expects them to move on their own. Tiny pellets of ice land on the man’s coat and in his white-gray hair that sticks up from his scalp like shorn wheat stubble.

Despite the weather, he’s bare-headed. Actual stubble roughens his chin and cheeks, and his eyes are like no color Wendy has ever seen before. Except they are. Impossibly, she knows them. She recognizes them and recognizes this man. His eyes are slate and storm and looking at them, Wendy feels a deck canting beneath her. Breath catches in her throat and her heart forgets to beat.

There are no oiled curls, no waxed mustache, and the coat the man wears is navy wool, not blood-red velvet. He is shorter than she remembers, but she was only a child when he held her prisoner at the point of a sword, tied her up to the mast of his ship along with her brothers and waited for Peter Pan to come save her. It cannot be, and yet there is not a single shred of doubt in Wendy’s mind.

“Hook.” She breathes the name, as if it could solidify him in her reality, or banish him. Wendy isn’t certain which she means to do.

“James.” It comes as an automatic response, a barely conscious correction he’s had to make too many times.

He grips a cane, letting it take his weight, and a faint tremor passes through him. Instinct makes Wendy reach to steady him, but she stops just short of touching him. She sees it the moment something shifts in his storm-colored eyes, the recognition that comes into them, and the surprise that isn’t as great as it should be.

“And you are… Wendy Darling.”

She offers no correction to her own name, merely staring at him. The air around them feels electric and magnetic all at once. Wendy imagines London as a map, folded against itself to bring the two points of their lives together at this precise moment in time. But how can Captain Hook be here? Is that what she felt last night, sitting before the fire, the sense of wrongness, the sense of something slipped into this world that doesn’t belong? Or is there something more?

“How…” Too many questions crowd her tongue, leaving her unable to form even one of them.

How did he know her? How is he here and still alive? How did he leave Neverland? How, how, how is he standing before her now in thickening snow?

Hook straightens. Another tremor passes through him, a pained expression following in its wake. Wendy thinks of Michael, her brother, and the way his leg has ached in the cold ever since he returned from the war.

“We…” Her voice falters. What can she say to this man—Peter’s immortal enemy, a pirate captain out of a fairy tale? Laughter threatens her, born of a wild jangling of nerves. He cannot be here. The first time she was in Neverland, she watched him die.

“Miss Darling?”

“Yes?” It isn’t her name anymore, but it is. Despite her marriage, she has always been, will always be, Wendy Darling.

“I feel as though we were intended to meet.” A cough shakes him, and Wendy thinks how frail he looks—gray all the way through, not just his eyes and his hair. “I—”

Before he can say more, it’s as though the world drops away from beneath her. Nothing changes, not perceptibly, and yet Wendy feels a terrible shadow hanging over them, worse than the feeling she had by the fire last night. Worse than anything since the night…

Fear goes to the heart of her, piercing like an arrow.

“Jane.” Her daughter needs her.

The sense in unshakable, a mother’s terrible instinct. Wendy turns, slipping on the icy streets and not caring that she does. Leaving Hook staring behind her, she runs.

THE IMMORTAL CAPTAIN

NEVERLAND – 22 YEARS AGO

His sword—wicked and curved, sharp as a smile—slashes empty air where the boy stood just a moment before. But Pan is already in the air, spinning, a foot, then two, above the tossing deck.

“You missed again!” Pan sticks his tongue out. “Poor old Hook.”

The boy lands, dancing a nimble circle as if the boards were not slick underfoot. He waves his sword, not even trying to strike Hook, his movements all flash and show.

A child. Only a child. An infuriating one, but a mere child nonetheless. How is it that he continues to elude every member of Hook’s crew, besting them all not once, but dozens of times? Or perhaps it is a hundred by now. Or more.

The fact that he doesn’t know unsettles him. Hook swings again to slash away the question of how many times he and Pan have fought. But it continues squatting, a shadow at the corner of his eye, refusing to be vanquished. Much like Pan himself.

There are more gaps in his knowledge than just this one. Parts of his mind are shrouded; there are borders between his own memories beyond which he cannot cross. It is much like the sea bounding this island. He has a ship at his command. It stands to reason that he could simply sail away, as far and as fast as he wishes, and yet always he returns.

Light flashes from Pan’s blade, sudden and terribly bright. It strikes Hook’s eyes, as sharp as a blow. He staggers back, raising his arm to drag it across his face as Pan’s taunting voice sounds again.

“Scaredy pirate! Scaredy Captain Hook.”

Anger seethes, sudden and hot, making him careless. Hook drops his arm and slashes, an ugly sweeping motion. Sloppy, when he knows better, coming nowhere near to striking Pan. Not that it matters. Each blow could be expertly timed to slip beneath his enemy’s guard, and they still wouldn’t land. In all the dozen—hundred?—times they’ve fought, he’s never so much as scratched the boy’s skin.

Hook clenches his jaw. Damn elegance and skill. He pushes forward with abandon, hacking wildly at Pan’s guard. All he wants is to land just one blow, wear Pan down and draw a spurt of bright blood. To see Pan’s eyes widen in fear, hear his mewling cry that Hook isn’t playing fair, that he is always supposed to win.

Hook bares his teeth, not giving Pan a moment to recover as he rains blow after blow. Every strike meets Pan’s sword, or misses him by inches, but Hook gains ground. Pan’s back strikes the rail. Hook’s lips stretch in a grin; at last, finally, he has—

A wave swamps the deck, sweeping Hook’s feet from beneath him. The ship and the sky change places and he crashes to the boards, blinking saltwater from his eyes. Pan’s laughter rings loud and clear as a bell, a sound like a wetted finger dragged across the rim of a glass.

“The old captain’s gone all soggy, wet, and moldy! Look at him. He’s a drowned rat.” Pan’s crowing voice reaches every corner of the ship.

Hook sees himself through the boy’s eyes—drenched, dark curls plastered to his skin, heavy velvet and ruffled silk—absurd and utterly vain—weighing him down. He looks worse than a drowned rat. He looks an utter fool.

“Captain!” A hand reaches to grasp his arm and pull him up.

Hook pushes the man away. He will not become an object of pity on his own ship. What sort of pirate cannot defeat a simple child?

“Pan!” Hook drags himself upright.

The name hangs in the air, answered by a cock’s crow. Then all at once, the boy himself hangs in the air before him. Behind him, the sun blazes so brightly Hook can’t look at him directly; Pan is a hole, an absence, a sharp-edged silhouette pinned upon the day.

Where it raged a moment before, the sea falls to calm, the waves going eerily still so that everything seems to hold its breath and wait on what will happen next. Weariness swamps him, as sure as a wave. He’s soaked to the bone, his muscles aching from the fight, and Pan remains as fresh as a new-cut daisy.

All Hook wants is dry clothing, and smoke filling his lungs. He wants to drink until he can’t remember his own name and sleep for a week. His shoulders slump. The answer to the question he tried to push away crawls from the fog-shrouded corners of his mind to crouch before him, grinning. He has fought Pan thousands of times, countless battles, and he has lost every single one.

The deck rolls. He braces himself as the boy flies a victorious circle, nowhere and everywhere at once.

“You’ll never best me, Hook! Perhaps I’ll cut off your other hand and feed it to the beast too.”

A chill seeps through him, another memory come to join the first. Teeth and scales and terrible jaws. He remembers his death; he remembers drowning.

Blood roars in Hook’s ears. He whirls in the direction of the piping voice, bringing his blade around. But Pan’s sword is there once again, blocking his and knocking it aside. Hook’s sword clatters to the deck. The point of Pan’s blade touches one of the buttons gleaming on Hook’s velvet coat. With no effort at all, Pan could drive the blade straight through his heart.

“Do it. Do it then.” Hook speaks low, barely moving his lips, a desperate, angry wish.

The blade at least would be swift. Pan narrows his eyes.

“That’s not how it goes. You must do it right, silly old captain.” Despite the gaiety of the words, Pan’s tone is blade-bright itself, and just as sharp.

Up in the rigging and hanging from the rails, dressed in skins and smeared with mud, Pan’s band of wild boys cheers. They are a nest full of raucous birds, roosting on every part of his ship.

“I know, I shall make you walk your own plank!” Pan’s eyes glitter, all malice and glee.

Hook thinks of a geode smashed open, a hollowness studded with jagged crystalline shine. That’s what Pan’s eyes remind him of; they are nothing human.

Soft waves lap the ship. Why isn’t his crew stopping this, coming to his aid? Didn’t someone try to help him just now? Hold out a hand? But he slapped them away. He commands a crew of grown men and Pan only commands a ragged band of boys. It should be easy, they should win, but it isn’t just Hook himself—they are all wooden puppets dancing at the end of Pan’s strings.

Hook clenches his muscles and wills himself to keep still. But Pan’s will is stronger. In this place, Pan’s will is everything. Hook’s arm jerks upward, beyond his control, and he shakes his hook in the air.

“You won’t get away with this, Pan! I’ll best you next time!”

The boy laughs, delighted at the play unfolding according to his whim.

“I am. Not. Your. Toy.” Hook grinds out each word, as painful as spitting up stone, leaving his throat bloody and raw.

If Pan hears the words at all, he ignores them.

“You’re a rotten, spoiled child, smashing your dolls together until you break them.”

“No more talking now. Talking is boring.” Pan’s gaze snaps to him, delight melting to reveal something colder, crueler—an ancient being behind the face of the child.

Pan no longer flits back and forth but hangs still in the air, becalmed as the sea. His eyes give Hook the sensation of looking out over dark waters, sensing rather than seeing what lies beneath them. He feels it then, the dull awareness that has been in the back of his mind all along, the thing he’s been trying to ignore. But he cannot ignore it any longer. It will rise at any moment, all armor-plated scales and hungering jaws.

Hook remembers drowning. And he has been here a hundred thousand times before.

Fear grabs hold of him, despite his determination not to be unmanned on his own ship, made cowardly before his men. Pan shouldn’t have the satisfaction, but his breathing is no longer under control. His pulse gallops, and he’s pulled helplessly behind it.

Pan. Panic. A hand slips beneath his skin, takes hold of his heart, and its grip is iron.

His death is an immutable fact. It exists before him and behind him, a thing that has happened before and will happen again—an endless circle. He and Pan and the creature below the waves are three points of a triangle, irrevocably joined. No matter what he does in this moment, nothing will change.

The shadow of a smile, a cold and terrible one, shapes Pan’s lips. Then they purse, sounding a whistle that rises and falls, piercing and sharp, skipping across the flatness of the water like a stone loosed from a child’s hand.

Hook turns, though he doesn’t want to, his legs marching him across the deck when he would dig in his heels. He glances to the side, his crew coming into focus at last as though they’d ceased to exist until this moment when Pan needed them to witness their captain’s humiliation.

These men—how many times have they fought together? How many times has he died in front of them? His mind churns and Hook finds he cannot even dredge up a single one of their names. They should be brothers in arms, loyal men willing to die for their captain, and yet he’s certain not a one of them knows a single thing about him beyond his shouted orders. Just as he knows nothing about them.

The realization hurts more than it should. The sensation of loss washes through him. There’s something missing, someone he’s forgotten. He scans his crew with a kind of desperation this time. Rough pirates, dressed in dirt and sweat-stained clothes, grime beneath their torn and ragged nails, hands calloused from the rigging. Except for one. Hook’s gaze snags on a man standing apart from the others. The man flinches, as if startled at being seen.

There’s a skip in Hook’s thoughts, a needle missing its groove. He’s never seen this man before, doesn’t know his name any more than he knows the others. Except the feeling of loss returns, stronger this time—a phantom limb aching even though he can clearly see it isn’t there.

The man meets Hook’s gaze, and there’s something like distress in his eyes. Hook wishes he could stop walking. If he just had a moment longer. If he could just talk to the man. If only he could remember.

He’s almost to the rail now, almost to the plank. He keeps his eyes on the man, trying to hold every detail, memorize him. It feels important. The man is dressed more neatly than the others; he wears no blade. His hair is tied at the nape of his neck, and his hands, Hook startles to notice, appear soft.

They’re uncalloused—a gentleman’s hands, not a pirate’s. It’s enough to jolt him from his fear and replace it with confusion. The man’s name almost rises to his lips, but just as quickly, the name is gone.

Pan jabs the point of his sword into the small of Hook’s back and Hook’s crew falls away once again. The entire world narrows, leaving Hook and Pan alone. The sword point stops just short of piercing the heavy fabric of Hook’s coat. He lifts one foot, then the other, climbing onto the plank and peering down at the water. The waves churn now, slow and sullen; the thing beneath them continues to rise.

“Now jump!” Pan jabs his sword again, as if Hook had a choice.

His knees bend of their own accord and he leaps. He strikes the water hard, his velvet coat blooming around him, petals unfurling and immediately growing heavy, dragging him down.

He remembers drowning.

And he remembers that drowning alone is not enough for Pan.

The beast appears in a rush of silvered bubbles. Jaws close on Hook’s leg, bones shatter-snapped as the creature jerks him rapidly through the waves. It’s almost fast enough to make him lose consciousness, but not quite. Up and down lose meaning. Water rushes up his nose, burning like fire. A flash of scales winds around him. The creature is vast and he cannot see all of it at once. Couldn’t even if his eyes didn’t blur with the salt. A clawed foot here, the dead-black center of a golden eye there, a flattened snout opening deadly wide.

It looks like a crocodile, but a crocodile is only an animal. It acts on instinct. It consumes in order to survive. This beast comes to the Pan’s call. It is malignant, fired with purpose, capable of hate. And it loathes him.

A small, dispassionate part of Hook’s mind tells him crocodiles are primarily freshwater creatures, a useless scrap of knowledge rising from the ether. They prefer rivers and swamps to the ocean. The thought is so out of place, so utterly unhelpful that even as the breath is crushed from his lungs and Hook dies for the hundredth, thousandth, millionth time, he dies laughing.

* * *

“Did it get dead again?” Cold fingers poke him.

“Not it, him. This one’s the captain.”

“Captain. Map-him. Slap-him.” The sing-song nonsense words are followed by trilling laughter uncomfortably like the chuckling of sea birds.

“Captain.” The third voice is dismissive, dripping scorn. “It still drowned, didn’t it? Useless land-thing.”

Hook rolls onto his side to vomit up seawater. It burns just as badly coming up as it did going down. His chest aches, his ribs battered. He can scarcely believe that every single one of them isn’t broken. Or perhaps they are. His throat, scraped raw, tastes of blood.

“Water.” The word rasps from him.

He’s lying on something hard. Soaked clothing clings to him. He’s too heavy to rise.

“Poor captain.” He can’t tell if it’s the first voice again, or the third, or another one altogether. Either way, the words aren’t said kindly, the tone cold, just on the edge of mocking.

He opens his eyes as the rough edge of a seashell pushes against lips. A trickle of water pours into his mouth, and he swallows greedily before remembering the last time the mermaids dragged him from the waves they tried to revive him with salt water. He nearly chokes, but the water is fresh and he swallows again and again until the shell is withdrawn. He struggles to sit.

Dim light comes through the wide mouth of the cave, a silvery-gray that could speak to pre-dawn, pre-twilight, or anywhere in-between. There’s no telling how long he was drowned this time, how long it took him to return.

All around him, in shallow pools and deeper ones, mermaids lounge. There’s a faint luminosity to the water, algae blooming in the dark. One of the mermaids slaps her tail against the water, a lazy motion. The sound echoes and ripples reflect on the ceiling, creating the unsettling illusion that the cavern is the sea floor and he’s still underwater.

It takes a moment to convince himself that oxygen does indeed flow into his lungs. The mermaids watch him, silent, waiting to see what he’ll do. They remind him of gulls, placid and stupid, but vicious when there’s food at stake.

He’s heard the legends of beautiful creatures luring men to their deaths. But whatever loveliness these mermaids have is more akin to the sleek beauty of sharks, or eels. Their faces are human, but subtly wrong. Strange shadows carve their cheeks and jaws, leaving their features a little too sharp, chins a little too pointed. Their flat eyes gleam in the dark.

He tries to forget the way they watch him as he takes stock. His legs are whole, his arms where they should be. Despite the tender ache of his flesh, he doesn’t seem more than bruised. The only part he’s missing is the only lasting wound the beast has ever dealt him—his hand, replaced by a hook. When he shifts, his bones feel splintered inside his skin, but that’s only an illusion—his mind telling him what should be, rather than what is.

The mermaid in the pool nearest him draws closer, curious, and rests her arms on a lip of rock. When he looks at her, she flicks her tail, showering him with water.

“Sad Hook, Mad Hook, Bad Hook. Pretty Peter beat you again.” She laughs and the others take it up, the sound echoing through the cavern.

Even this close, he isn’t always sure which one of the mermaids is speaking at any given time. As much as they remind him of sea-birds, they also remind him of bees—a hivemind, indistinguishable to his eye. He’s never been able to tell the mermaids apart, to know whether he’s met a particular shoal before. They’re changeable, fluid like the element they swim in. Their faces don’t stay in his mind. Like those of the boys Pan leads. Like those of his crew.

“Bad, bad Hook. He doesn’t know how to beat Pretty Peter, does he?” The voice bounces from the walls, further disorienting him.

The tone is fluting, musical, but also eerie. The mermaids dragged him from the water, but if their mood changes and they grow bored, the lot of them could easily tear him apart.

“It doesn’t know anything at all.” Another voice, or the same, scoffs. “Stupid pirate. It doesn’t know the stories. It doesn’t know Pretty Peter’s secret.”

A flash of teeth and eyes that remind him for a moment of Pan’s. Otherworldly. Unreal.

“What secret?” Hook fixes his attention on the mermaid in front of him, the closest, the one he can see most clearly. The others are mere shadows in their pools and on the stone that resembles hardened melted wax. But she isn’t the one to answer him, or at least he never sees her lips move.

“Ooh. Buried long ago. Would you listen if we told, scold, bold? No. Mermaids are lowly creatures. Like birds squawking, yes?”

He keeps his gaze fixed on the mermaid in front of him in case she is the one talking. She tilts her head to the side, her gaze canny, unnerving. Can they read each other’s minds? Can they read his as well?

“Tell me your story. I’ll listen.” Something prickles at the back of his skull—a memory from the shrouded corner of his brain? Has he asked for this story before? More laugher flutters around the cave.

“A secret!” a voice pipes up and others crowd to follow it, spilling one over the other, blurring together.

The mermaids forget their intention to play keep-away with their knowledge, eager to prove what they know and he does not.

“A treasure.”