Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

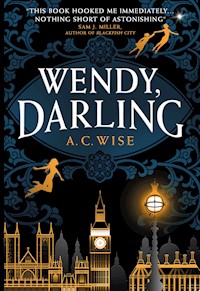

A lush, feminist re-imagining on what happened to Wendy after Neverland, for fans of Circe and The Mere Wife. LOCUS AWARD FINALIST FOR BEST FIRST NOVEL Find the second star from the right, and fly straight on 'til morning, all the way to Neverland, a children's paradise with no rules, no adults, only endless adventure and enchanted forests – all led by the charismatic boy who will never grow old. But Wendy Darling grew up. She has a husband and a young daughter called Jane, a life in London. But one night, after all these years, Peter Pan returns. Wendy finds him outside her daughter's window, looking to claim a new mother for his Lost Boys. But instead of Wendy, he takes Jane. Now a grown woman, a mother, a patient and a survivor, Wendy must follow Peter back to Neverland to rescue her daughter and finally face the darkness at the heart of the island…

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 472

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1: Darling

2: Never, Never

3: Second Star to The Right

4: Lost Boys

5: Straight On ’Til Morning

6: Hide and Seek

7: Let’s Play War

8: The Hunt

9: The Frozen Girl

10: Make Believe

11: The Forbidden Path

12: Peter’s Secret

13: Here be Monsters

14: Shadow Play

15: Home

Acknowledgments

“This book hooked me immediately with Wendy’s voice and rage and longing… what Wise does with the Peter Pan mythos here is nothing short of astonishing”

Sam J. Miller, Nebula Award-winning author of Blackfish City

“A dark and delightful retelling of Peter Pan. Wendy, Darling is a gorgeous achievement, and one you don’t want to miss”

Gwendolyn Kiste, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of The Rust Maidens

“Wendy, Darling is a daring, gothic re-envisioning of everything we think we know – and an important, vivid adventure”

Fran Wilde, two-time Nebula award-winning, World Fantasy finalist author of Updraft

“Richly imagined, surprisingly dark, and heartbreakingly beautiful, this daring reimagining doesn’t only revisit the myth, it brings it up to date”

Marian Womack, author of The Swimmers

“The horror-tinged feminist Peter Pan retelling I never knew I needed… a brilliant re-imagining of a classic boy’s club story”

Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam, author of ‘Mantles’

“A gorgeously imagined journey into the unfathomable depths of childhood myth”

Kelly Robson, author of Gods, Monsters and the Lucky Peach

“Neverland is more nightmare than dream… This rich tale of memory and magic is sure to resonate with fans of reimagined children’s stories”

Publishers Weekly

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Wendy, Darling

Print edition ISBN: 9781789096811

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789096828

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition June 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© A.C. Wise 2021. All rights reserved.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For everyone who has ever dreamed of flying

DARLING

LONDON 1931

There is a boy outside her daughter’s window.

Wendy feels it, like a trickle of starlight whispering in through a gap, a change in the very pressure and composition of the air. She knows, as sure as her own blood and bones, and the knowledge sends her running. Her hairbrush clatters to the floor in her wake; her bare feet fly over carpeted runners and slap wooden floorboards, past her husband’s room and to her daughter’s door.

It is not just any boy, it’s the boy. Peter.

Every inch of her skin wakes and crawls; the fine hairs all along the back of her neck stand on end—the storm secreted between her bones for years finally breaking wide. Peter. Here. Now. After so long.

She wants to shout, but she doesn’t know what words, and as Wendy skids to a halt, her teeth are bared. It isn’t a grimace or a smile, but a kind of animal breathing, panicked and wild.

Jane’s door stands open a crack. A sliver of moonlight— unnaturally bright, as if carried to London from Neverland— spills across the floor. It touches Wendy’s toes as she peers through the gap, unable for a moment to step inside.

Even though she’s still, her pulse runs rabbit-quick. Backlit against that too-bright light is the familiar silhouette: a slender boy with his fists planted on his hips, chest puffed out and chin tipped up, his hair wild. There is no mistaking Peter as he hovers just beyond the second-floor window. She blinks, and the image remains, not vanishing like every other dream stretched between now and then. Between the girl she was and the woman she’s become.

Of course, Wendy thinks, because this may not be the house she grew up in, but it’s still her home. Of course he would find her, and of course he would find her now. Bitterness chases the thought—here and now, after so long.

At the same time, she thinks no, no, please no, but too-long fingers already tap the glass. Without waiting for her say-so, the window swings wide. Peter enters, and Wendy’s heart swoops first, then falls and falls and falls.

Once invited, always welcome—that’s his way.

Peter doesn’t notice Wendy as she pushes the hall door open all the way. He flies a circle around the ceiling, and she wills her daughter to stay asleep, wills her tongue to uncurl from the roof of her mouth. Her legs tremble, holding her on the threshold, wanting to fold and drop her to the floor. It’s such an easy thing for him to enter, and yet her own body betrays her, refusing to take one step into her daughter’s room, in her own house.

It’s unfair. Everything about Peter always was, and it hasn’t changed. After years of her wanting and waiting, lying and hoping, he’s finally here.

And he isn’t here for her.

Peter lands at the foot of Jane’s bed. The covers barely dimple under his weight, a boy in form, but hollow all the way through. Maybe it’s the motion, or the light spearing in from the hall behind Wendy, but Jane half-wakes, rubbing at her eyes. A shout of warning locks in Wendy’s throat.

“Wendy,” Peter says.

Hearing him say her name, Wendy is a child again, toes lifting from the ground, taking flight, about to set off on a grand and delicious adventure. Except he’s not looking at her, he’s looking at Jane. Wendy bites the inside of her cheek, bites down in place of a scream. Does he have any idea how long it’s been? Swallowing the red-salt taste of her blood finally unlocks her throat.

“Peter. I’m here.” It isn’t the shout she wishes, only a half-whispered and ragged thing.

Peter turns, his eyes bright as the moonlight behind him. They narrow. Suspicion first, then a frown.

“Liar,” he says, bold and sure. “You’re not Wendy.”

He makes as if to point at Jane, evidence, but Wendy’s answer stops him.

“I am.” Does he hear the quaver, as much as she tries to hold her voice steady?

She should call Ned, her husband, downstairs in his study, either so absorbed in his books or asleep over them as to be oblivious to her flight down the hall. It is what a sensible person would do. There’s an intruder in their home, in their daughter’s room. Jane is in danger. Wendy swallows, facing Peter alone.

“It’s me, Peter. I grew up.”

Peter’s expression turns into a sneer, Jane forgotten, all his attention on Wendy now. Jane looks in confusion between them. Wendy wants to tell her daughter to run. She wants to tell her to go back to sleep; it’s only a dream. But the mocking edge in Peter’s voice needles her, pulling her focus away.

“What’d you go do that for?”

Wendy’s skin prickles again, hot and cold. The set of his mouth, arrogant as ever, the flicker-brightness of his eyes daring her to adventure, daring her to defy his word-as-law.

“It happens.” Wendy’s voice steadies, anger edging out fear. “To most of us, at least.”

Peter. Here. Real. Not a wild dream held as armor against the world. The years unspool around her as Wendy finally manages to step fully into her daughter’s room. And that armor, polished and patched and fastened tight over the years, cracks. For a terrible moment, Jane is forgotten. Wendy is a creature made all of want, aching for the cold expression to melt from Peter’s face, aching for her friend to take her hand and ask her to fly away with him.

But his hand remains planted firmly on his hip, chin tilted so he can look down at her from his perch on the bed. Wendy takes a second step, and her armor is back in place. She takes a third step, and anger churns stronger than desire—dark water trapped beneath a thick layer of ice.

Wendy clamps her arms by her side, refusing to let one turn traitor and reach toward Peter. She is no longer the heartbroken girl left behind. She is what she has made of herself over the years. She held onto the truth, even when Michael and John forgot. She survived being put away for her delusions, survived the injections, calmatives, and water cures meant to save her from herself. She fought, never stopped fighting; she refused to let Neverland go.

It’s been eleven years since St. Bernadette’s, with its iron fences and high walls, full of frowning nurses and cruel attendants. A place meant to make her better, to cure her, though Wendy knows she was never sick at all. And here is the proof, standing before her, on the end of her daughter’s bed.

Wendy straightens, hardening the line of her jaw, and meets Peter’s eye. In the last eleven years she’s built a life for herself, for her husband and her daughter. She is not that lost and aching girl, and Peter has no power over the Wendy she’s become.

“Peter—” Wendy hears her own voice, stern, admonishing. The voice of a mother, but not the kind Peter ever wanted her to be.

Before she can get any farther, Peter shakes his head, a single sharp motion, dislodging her words like a buzzing gnat circling him. His expression is simultaneously bored and annoyed.

“You’re no fun.” He spins as he says it, a fluid, elegant motion. Peter blurs, and Wendy thinks he’s about to leave, but instead he seizes Jane’s hand. “Never mind. I’ll take this Wendy instead.”

Peter leaps, yanking Jane into the air. Jane lets out a startled cry, and Wendy echoes it—a truncated burst of sound. She isn’t quick enough to close the space between them as Peter dives for the window, Jane in tow. Instead, Wendy falls forward, bashing her knee painfully and catching herself on the window sill.

Wendy’s fingertips brush Jane’s heel and close on empty air. Peter spirals into the night, a cock’s crow trailing in his wake, so familiar, so terrible it overwhelms her. Wendy doesn’t hear if her daughter calls for her; the only sound in the world is the ringing echo of Peter’s call as two child-sized figures disappear against a field of stars.

LONDON 1917

“What is this place?” Wendy asks as the hired car comes to a halt outside a massive iron gate surrounded by a dense green hedge too tall to see over.

Visible through the gate, a long path of crushed stone leads to an imposing building, brick facade and blank-eyed windows glaring out at them. John sighs, his voice tight.

“This is St. Bernadette’s, Wendy.”

John doesn’t wait for the driver. He opens his door and circles to open Wendy’s as well, taking her arm either to help her or keep her from running away.

“We spoke about this, and Dr. Harrington, remember? He’s going to help you get well.”

Wendy bites the inside of her cheek; of course she remembers. Her brothers are the forgetful ones; all she can do is remember. But the bitter, petty part of her wants to make this as difficult as possible for John. She wants to make him explain it over and over again, how he plans to leave her here, wash his hands of his mad sister. What would their parents think? If Mama and Papa had never boarded that cursed ship, the one meant to be unsinkable until it met an iceberg, would they allow John and Michael to treat her this way? She’s thrown that very question at him more than once, watching his face crumple and taking delight in it. Yet, through it all, her brother’s resolve hasn’t wavered.

Lines gather around John’s mouth, the same expression he wore as a child, always trying to be so serious and grown up. Only in Neverland had Wendy ever seen him truly be a little boy. Playing follow the leader, chasing Peter through the treetops, flying. Why would he ever want to forget that and leave it behind?

She studies John in profile as they approach the gate, the way the sun highlights the proud line of his nose, the firm set of his jaw, catching in his glasses and erasing his eyes. His poor vision had kept him from the war, but so many other burdens—herself included—had fallen on him instead. He’s still young, twenty-one, and just barely a man now, but already his shoulders stoop, carrying the weight of years of a man twice his age.

He must feel her watching, but he doesn’t look her way. The ache in Wendy’s chest is replaced by the first edging-in of panic. John truly means to go through with this; he means to have her committed.

She pushes the trapped-bird flutter down as the gate clanks open, guided by a man in a white uniform, his expression stoic. John looks briefly pained, and for a moment, Wendy considers relenting. At least he had the decency to see her imprisoned in person. Michael refused to accompany her. But why would he? The way she treated him was the final straw that forced John’s hand. She screamed at her baby brother, she hurt him when he was already so fragile after coming home from the war, broken in body and broken in soul. John had no choice—he’s sending her away for her own protection, and even more so for Michael’s.

Wendy looks away from her brother, from the man in white, her throat suddenly thick. If she keeps looking at John she will break, and she’s determined to be jailed with her head held high.

She focuses on the grounds to distract herself. Once upon a time, this place would have been a fine country estate, and it still looks the part. On either side of the path, emerald-bright lawns stretch away to the iron-laced hedges in front, and high stone walls on the three other sides. There are flower beds and shade-giving trees, croquet hoops staked into the grass, and small groupings of tables and chairs. It’s almost idyllic. Here, she could forget the rest of the world is at war. She could—if she were to allow herself—forget that St. Bernadette’s is a cage, but that’s something she never intends to do.

Despite her best efforts, panic spreads, blood beneath the skin turning to a bruise. Should she try one more time to explain herself? If she lies convincingly enough, perhaps John will let her stay home and help with Michael. His leg still pains him, a lingering effect of the shrapnel that tore it apart, but the dreams are worse. Wendy and John have both woken to the sounds of Michael’s troubled sleep, believing himself back in the trenches, or in the base hospital awaiting another surgery before finally being sent home. If she could encourage him in his therapy, and be there to soothe the memories and vision away, maybe Michael himself would even forgive her in time.

But, no, she’s out of chances. John and Michael may not see it, but she did try. And she failed. After their parents’ deaths, she tried to be a mother, keep everyone fed and clothed. A disinterested uncle had come to stay with them, a guardian in name only. Their mother’s brother, a man Wendy had met only once as a very young child. He had done only the bare minimum required of him to look after their welfare; all else had fallen to Wendy, John, and Michael themselves. John, always so serious, had done his best to become the man of the house, taking all the responsibility onto his shoulders that he could, losing even more of his childhood in the process. If any bit of Neverland had remained in his mind, it vanished then. So young, and yet too old for silly stories and games, for make-believe.

None of them had taken time for grief. It hadn’t been afforded to them. Their uncle certainly had no interest in giving space to their sorrow; any display of emotion at all was considered unseemly. Then Michael had gone to war and come home broken. And the silences that stretched between her and John, between all of them, had grown worse.

She should have kept to those silences, but the truth came bursting out. Watching her brothers suffer—John with the weight of the world on his shoulders, Michael with his eyes full of ghosts—Wendy couldn’t hold her tongue. With John of age to truly become the man of the house, and their uncle finally gone, she’d wanted to remind them of happier times, or so she’d told herself. Only instead of speaking reasonably, she’d shouted. Lashing out, insisting they see the world her way, refusing to listen. The more they’d resisted her, the more she’d kept on shouting. Until she couldn’t see her way clear to stopping, couldn’t find her way back home to common ground.

Anger became her habit, Neverland her defense. The more they’d tried to draw her out, the further she’d retreated into their shared past, to save herself from their denial, to save Neverland itself, as determined to remember it as John and Michael were to forget. No, John might as well ask her to cut off a limb; she wouldn’t be able to do that either. She cannot, and will not, deny Neverland. Even now.

Wendy stiffens as Dr. Harrington, impeccably dressed as always, walks down the path to join them. She keeps her gaze on his polished shoes, timing her breath to his steps. White stone crunches beneath his soles; his watch chain bounces, glittering with his motion. Anything to avoid looking into his eyes, into the face of the man who will be her jailor for who knows how long.

Even when the footsteps stop, Wendy keeps her chin tucked down. The uniformed man who opened the gate lines his shoes up—far more scuffed and plain—just behind Dr. Harrington’s bright ones. His place at Dr. Harrington’s shoulder is a subtle threat, and despite herself, Wendy looks up. The uniformed man stands a good head taller than Dr. Harrington. There’s a squareness to him, his shoulders broad, his hair cut neat and close. She wonders why he isn’t overseas, fighting.

There’s a name stitched over the man’s breast pocket— Jamieson. He catches her looking and his mouth twists, the expression an ugly one. Wendy starts, a fresh thrill of fear going through her. She has done nothing to this man, and yet Jamieson looks at her as though he wants to do her harm. She knew boys like him in Neverland, bullies following at Peter’s heels, but held in check by the brightness of his games. To Jamieson, she is a wild animal to be muzzled and chained at the slightest excuse. A yearling to be broken if she refuses the saddle.

“Mr. Darling.” Dr. Harrington extends his hand to John, breaking Wendy from her dark thoughts.

Bitterness rises in her all over again, fear momentarily forgotten. Dr. Harrington and John shake hands, so civilized—neither of them looking at her—as though she were a mere business agreement, not a patient or a beloved sister. And all the while, John still has his other hand on her arm. She pulls away roughly.

“I am perfectly capable of walking on my own.” The words snap, and she steps away from her brother; more pettiness. All three men watch her, as if she might turn into a bird and fly away.

Wendy lifts her chin, but does not look at any of them. She won’t even say goodbye. Let that sit on John’s conscience. Without leave, she walks past Dr. Harrington toward St. Bernadette’s front doors. If this is to be her fate, she’ll go to it on her own, not dragged or guided. Her boot heels strike hard against the crushed stone even though her legs tremble beneath her skirt, but she refuses to slow or give in.

“Wendy!” John’s footsteps scuff the path behind her.

It puts even more resolve into her step, and Wendy quickens her pace. She doesn’t turn, doesn’t stop, and hears Dr. Harrington intercept her brother, his voice smooth and practiced, used to soothing patients.

“Perhaps it’s better this way, Mr. Darling. Your sister is in good hands here. Once she’s had a chance to settle, you can visit her, of course.” Implied is that Wendy will be more docile then. There isn’t a speck of doubt in Dr. Harrington’s voice—he will see her cured.

Despite herself, Wendy’s shoulders hunch. Dr. Harrington’s words grate, his tone scraping at her, through flesh to bone. She wants to turn and pummel him, closed fists against his shoulders and chest, but she forces her arms to hang loose at her sides. She’s broken more plates and cups in her rages at Michael and John than she cares to count. For once, she must keep her temper under control.

“Miss Darling.” Dr. Harrington catches up to her, Jamieson still shadowing him. Wendy doesn’t turn to see if John remains on the path, watching. “Allow me to show you to your room.”

Dr. Harrington says the words as though she is a guest, free to leave whenever she wants.

“I think you will find it most amenable here. Our staff and facilities are excellent. The only thing we want in this world is to make you well.”

Wendy’s mouth opens, but no sound emerges. Somehow, they’ve reached the end of the path, climbed the steps. The door frames them. Dr. Harrington takes her arm. Jamieson stands behind him. Even if she were to pull free, there is nowhere to run.

“This way.”

In her determination and pride, she’s walked herself right into the trap, and now it’s ready to snap closed behind her. It’s too late. One more step, and Wendy crosses the threshold. The air changes immediately, heavy and dim. Wendy feels the loss of the sky overhead like a stolen breath. She hadn’t realized how much comfort she’d been drawing from that perfect stretch of blue.

She glances to the ceiling, pressed tin, hung with a chandelier. Rich carpets in patterned jeweled tones cover the floor of the entryway, lovely but worn. A few steps in, and the ceiling gives way to a high, open space. Curved staircases at either end of the foyer sweep up to a balcony that overlooks the ground floor. A stained-glass window lets through light, but its quality tells Wendy it doesn’t look onto the outside. Everything here is enclosed, safe, but false.

Dr. Harrington leads her past a reception desk without even a glance at the woman in a nurse’s uniform seated there. The woman doesn’t glance up either, and Wendy suppresses a shiver at the coldness of it all. She is merely a transaction, one of how many patients marched through the doors because they are inconvenient to their families, or worse, actually sick. Is there anything in this place to heal them?

Wendy tries to take in more of her surroundings, but Dr. Harrington speeds his pace, taking her past a common room with large windows overlooking the garden, and a smaller interior room where two nurses rest their feet. They turn a corner. The air changes again, and Wendy feels it immediately—a transition from the old country estate house to a newly constructed wing.

Fresh panic gnaws at her, and this time it refuses to be tamped down. The hallway stretched before her is plain, and there is nothing hospitable about it—all pretenses dropped. This is not a country estate, a place where people come to rest and get well. It is a place where people are locked away. Where patients scream and no one answers.

Doors line the hallway, set with small glass windows. More twists and turns carry her over gleaming checkerboard tiles. Wendy feels numb, dizzy. They pass larger doors spaced further apart. Medical facilities, treatment rooms. The size of the building eludes her; she can’t hold a picture of the whole in her mind.

“Please, Dr. Harrington—” Wendy’s voice emerges breathless, a weakness she would rather not admit but can’t help. Something in this place presses down on her, and she gulps for air.

And then she stops, the full weight of her body holding her in place despite Dr. Harrington’s hand on her arm. A girl with long, dark hair passes, going the opposite direction, head down so Wendy can’t see her face properly. Even so, the sight of her strikes Wendy as a physical blow, and a name rises to her lips so swift she almost speaks it aloud—Tiger Lily.

She’s sworn to herself to keep Neverland secret here, to guard it close to her chest. Whatever John has told Dr. Harrington can only be half of the truth at best. If Wendy were to tell him anything real, Dr. Harrington would only take to it with a microscope and a scalpel, turning it into something ugly. So she swallows down Tiger Lily’s name, even though it burns, looking away as the girl walks past.

As much as she might wish it otherwise though, her mind rebels. She can’t help recalling a bank of emerald grass beneath the silver drooping bows of a willow tree. Locked away from all the world, she and Tiger Lily wove crowns of reed, linked their hands together—brown and white—and set the crowns on each other’s heads.

The memory aches. She can’t stop herself from glancing up, but the girl has already moved down the hallway. The loss in her wake makes it hard for Wendy to breathe, but she forces herself to keep going. Dr. Harrington looks at her, a frown of disapproval that she has upset the natural order of things.

The girl isn’t Tiger Lily. She knows that, and to distract herself, Wendy tries to reconstruct the girl’s actual appearance from that brief glance, and after a moment, she convinces herself that the girl doesn’t resemble Tiger Lily at all. It was only her mind playing tricks, wanting something familiar in this place of terror, something that felt like home.

“Here we are.” Dr. Harrington’s voice, falsely bright and sharp-edged, brings her back.

He opens a door, unlocking it swiftly and dropping the key into his pocket as though Wendy won’t notice. The opened door reveals a spare, cell-like room, purpose-built with white-painted walls, a narrow bed, and a single chair. The window has no curtains, and on the outside there are bars.

“We have what we like to think of as patient uniforms here.” Dr. Harrington smiles.

The expression is awkward, as though he’s letting Wendy in on a joke.

“Everyone here is equal, no matter where they began. They are all here to get well.”

He gestures to a plain cotton dress folded atop the bed, nearly the same pale gray as the blanket it lies upon. The girl they passed in the hall, the one who isn’t Tiger Lily, wore the same.

With his next words, Dr. Harrington’s tone shifts, all efficiency, dropping the welcoming pretense that Wendy is merely a guest. He speaks by rote, addressing a patient whose individual wants and concerns he means to dismiss, and leaves no space for Wendy to respond.

“A nurse will be along shortly to help you change, and your own clothing will be stored for safekeeping. Your door will be locked at night until you are acclimated. This is for your safety, of course. Meals are served in the dining hall, unless extenuating circumstances dictate otherwise. During your first few days you will be brought meals in your room, again, until you adjust.”

Before she can question what extenuating circumstances might be, Dr. Harrington pats Wendy’s hand, his expression warm and fatherly again. The gesture, she presumes, is meant to be reassuring. It is anything but.

She keeps her lips firmly over her teeth, hiding them. She wants to snarl. She wants to run. She wants to break and fold into herself—abandoned, doubted, disbelieved. She does none of these things, standing still with her hands clasped before her as Dr. Harrington withdraws. The door closes and she hears the tell-tale scrape of a key in the lock.

Silence fills up the corners of the room, a pressure against her skin. Wendy sits on the edge of the bed. Springs poke through the thinness of the mattress. There is a finality to the stillness.

She has no love for the particular dress she’s wearing, but the thought that she’ll have to give it up for the shapeless gray uniform beside her makes her want to scream. The fact that she will not even be trusted to change her own clothing, like an unruly child, is even worse. She fingers the cuffs of her sleeves, touches the rough woolen blanket, trying to let the simple feel of the fabric ground her. It does nothing.

She breathes, focusing on the movement of her ribs, the expansion of air in her lungs. All of this is only a test. Tomorrow, John and Michael will bring her home. She’ll learn to behave. No more broken plates. No more tantrums.

Deep down, Wendy knows John and Michael aren’t coming for her. At least not until she proves she can behave, until Dr. Harrington deems her well. And if that never occurs? If John decides it is more convenient to forget one more thing from his childhood, and leave her safely locked away? Through the bars on the window, the sky is brutalized, chopped into neat sections. No one is coming for her. No one at all. Not even…

The weight is too much. Wendy snatches the pillow from the bed and crushes it against her mouth. She gasps air in shallow breaths, each growing more ragged until her lungs threaten to burst.

Then into the terrible silence around her, pillow-muffled, full of fear and rage, Wendy Darling screams.

LONDON 1931

Wendy returns to Jane’s window. The inspectors from Scotland Yard have come and gone. For hours her house has been filled with men’s voices—their rough laughter when they were unaware of her listening, their questions that she can give no answers to, the stink of tobacco clinging to their uniforms and skin. She hates every last one of them. Now, only her father-in-law remains, and she hates him most of all.

Ned’s father arrived with the inspectors, without Wendy or Ned having spoken to him about what occurred. Wendy can’t help but believe that her father-in-law arranged with the chief inspector—a personal friend—that he would be contacted immediately should any emergency calls originate from their house. Anger simmers beneath her weariness, made worse by the fact that she can say none of this aloud. Silently, she curses her father-in-law, and curses Scotland Yard for spineless cowardice.

As if she and Ned are insufficient on their own to keep their household safe. The thought brings bitter laughter, but Wendy traps it behind her lips. Oh, but she is insufficient. The knowledge twists blade-sharp, stealing her breath. She lost Jane. She let Peter steal her daughter away.

Wendy knots her fingers, staring at the darkened streets beyond Jane’s window. She is tired to the bone, and at the same time, sleep is the farthest thing from her mind. The inspectors and her father-in-law asked her dozens of questions, then asked them all over again to Ned. As if by virtue of his sex he must know more than she ever could. And all the while, questioning or silent, her father-in-law had glared at them both.

Untangling her fingers, Wendy wraps her arms around her upper body, holding onto her elbows to keep from flying apart.

She lied. To the men from Scotland Yard. To her father-in-law. Even to Ned. She told them she simply woke—a mother’s instinct—and came to her daughter’s room to find her gone. The aftertaste of dishonesty lies thick on her tongue. But what else could she say?

She’s been lying to Ned for years, withholding this one vital piece of truth. For eleven years she’s played at being a good wife, a good mother; there have been days she’s even managed to convince herself. But now it’s all falling apart, as much of a sham as her mothering of Peter and the boys in Neverland.

She chose this, she tried, and still she failed. It takes everything in Wendy not to shout, to hurl everything she can lay her hands on and scream the truth until her throat bleeds. She is not, and will not, ever be good enough for anything but lies and make-believe.

She leaves the window, pacing through Jane’s room. Her fingers trail over butterflies carefully pinned under glass, over collections of rocks and seashells and leaves, all held in cases of their own. Jane’s books. The globe atop her shelf, marked with pins for all the places her daughter wanted to visit. Of all those lands she dreamed of, Jane couldn’t have pictured Neverland. Wendy should have warned her. She should have…

Wendy lifts a butterfly case. The label is written in Jane’s neat hand—neater than Wendy’s ever was at her age. Holly blue, Celastrina argiolus. Jane caught it on the holiday they took in Northumberland, so excited she’d clutched the jar like a treasure all the way home.

The memory tightens Wendy’s throat, threatening her with tears. She wants to smash the case, smash everything in the room. Instead, she sets the glassed-in butterfly down as gently as she can.

“Come away, darling.” Ned touches her shoulder.

Wendy jumps. She never heard him enter. How long has she been standing here, staring? His hand is warm and strong on her shoulder and she wants to shrug him away, but she forces herself to turn.

Tiny threads of crimson in Ned’s eyes mark his own grief, and the tightness in his posture is unmistakable. Beneath his neatly trimmed moustache, his lips press a thin line. He’s as afraid for Jane as she is, maybe more so, because he understands even less of what’s going on. She should tell him. She should, but she won’t.

“Where’s Mary?” The words emerge sharp, in place of comfort.

Wendy hates herself, but even so she can’t stop herself from looking past Ned’s shoulder as if Mary might appear in the doorway carrying a tray laden with tea. Her pulse catches. Her father-in-law stands there instead, light from the hallway transforming him into an imposing blot of shadow.

“I sent Cook home.” Ned stresses Mary’s title, his tone matched to hers.

Wendy hears the brittleness under it, but she straightens, stepping back an inch as if too much closeness, even between husband and wife at a time like this, might be improper somehow. She cannot see her father-in-law’s face for the light behind him, but she imagines his frown. Wendy knows his opinion of Mary, and she knows it isn’t one Ned shares. Under normal circumstances, he never would have sent her home. He would call her Mary, rather than Cook, and he might be the one to make tea for all three of them as they shared their worries over Jane. But as long as Ned’s father is here, none of that matters.

To her father-in-law, Mary is that girl—always emphasizing the word. A bad influence on your household, and by that, Wendy knows he means a bad influence on her. You know how their kind are. And those are only the words he’s spoken in her hearing. To Ned, Wendy knows he’s said far worse, calling Mary savage and heathen, dangerous and untrustworthy. Only Ned’s steady touch, his calm, has kept her from lashing out at her father-in-law and forbidding him from ever setting foot in her home again. Not that she could. Despite everything she has worked to build for herself in the past eleven years, so much of Wendy’s life is by her father-in-law’s grace alone.

In addition to being Ned’s father, he is Ned’s employer, and John’s. She suspects, though her brother refuses to speak to her candidly on the matter, that John is indebted to him financially. There was a time, before he began working for Ned’s father, when John put his trust in the wrong man, investing money their parents had left them in what appeared to be a promising business venture, thinking himself a grown man when he was still so young.

Most of this Wendy has gleaned from overheard snatches of conversation, snooping and sleuthing on her own. Any time she’s asked directly, her brother always steers the conversation away, telling her business dealings are not a woman’s concern.

It’s more than that though. A delicate balance exists between Ned and his father, and thus between her and Ned’s father, and even her and Ned—one she is still trying to understand. Ned fears his father’s disapproval, and he craves his respect, craving it all the more fiercely every time it is withheld. Despite everything, despite the man Wendy knows Ned to be deep down, part of her husband still longs to be his father’s image of what a man should be. Thus his bluster before Scotland Yard, thus his acquiescence to every one of his father’s rules. It is an irony Ned doesn’t seem to realize. His father respects strength, yet Ned remains cowed. What would happen, she wonders, if he stood up for himself, if he demanded respect for who he is, and not who his father wants him to be?

“Of course,” Wendy says. “Very proper.”

She hears the frost in her voice, swallows around it like a lump of ice in her throat. Ned flinches, the slightest of motions. Is it from her, or from resisting glancing at his father? His eyes find Wendy’s, begging her for patience, even now, when their daughter is missing.

He’s hurting, as unhappy about his father’s presence as Wendy, but they must keep up the facade. Wendy knows. She understands. But her daughter is missing. Peter stole Jane from her very bed, and every moment her father-in-law spends here, every moment they play pretend, is a moment she could be out there saving Jane.

Wendy almost lays a hand on Ned’s chest. It would be a small gesture of appreciation, a bridge between them, a sharing and lightening of their burden, but she can’t help the anger rising and rising in her like a tide. She lets her hand fall. It’s her father-in-law she hates, but Ned is closer. And even if he was only bowing to his father’s pressure, Ned is ultimately the one who sent Mary away.

She imagines Mary arguing, Ned insisting with hurt in his eyes, and now Mary sitting alone in her tiny rented room. Mary is the only person who might understand. Wendy can’t speak to John or Michael, and even if she undid years of lies and told Ned where Jane is, would he believe her?

Her fingers curl into the fabric of her skirt, bunching it into a fist before she forces herself to let go. She won’t lay a hand on Ned’s chest to comfort him, but she won’t lash out either. In this moment, it’s all she can do.

Movement draws Wendy’s eye, Ned’s father shaking his head before he withdraws. Footsteps echo in the hall, pointed as he descends the stairs. Wendy bows her head, still keeping the space between herself and her husband. Ned’s shoulders hunch. Each footfall is a frown, a harshly spoken word. Then eventually the front door opens, and closes, and they both slump without moving closer together.

When Wendy does look up, she finds Ned watching her as if she might shatter, the pieces of her embedding themselves in his skin. Wendy presses her lips into a close line. If she speaks, if she says anything at all, she might blurt out the truth. She knows the bluster Ned put on in front of the men from Scotland Yard was all for his father’s benefit, acting the masterful head of his household with no time for the nonsense of women. She shouldn’t resent him for it, but she can’t quite forgive him either. It’s unfair, expecting his trust and support when she hasn’t given it in return. But she can’t be that bridge. Not now. Not while her daughter is gone. The kindest thing she can do is withdraw.

“I’m tired,” she murmurs, looking down.

If she looks up, she’ll see the hurt in his eyes, all the truths she’s failed to tell him. When he answers her, Ned’s voice is strained, as though still performing for her father-in-law.

“Of course, darling. You should rest.”

Wendy dips her head. She doesn’t intend to look up as she steps past him, but Ned touches her arm.

“The inspectors are doing everything they can. They’ll find Jane and bring her home.”

Despite her better judgment, Wendy meets her husband’s eyes. The loss in them is dizzying, threatening to break her all over again. The stutter—nearly vanished in the eleven years she’s known him—betrays itself when he speaks, a sign of his exhaustion. She should say something kind, reassure him, but she’s already wasted too much time. She needs to go after Jane, and she can’t do that with Ned watching over her. Wendy pinches the inside of her arms to keep them crossed.

“Of course.” Her jaw aches with holding back words. “You’re right. The police will take care of everything. I’ll go rest. You’ll fetch me if you hear anything?”

She says it knowing there will be nothing to hear. Scotland Yard won’t find Jane. Only Wendy herself can do that. By the time Ned comes looking for her, she’ll be long gone.

“Yes, darling. Of course I will.” Ned kisses her brow. Wendy stands perfectly still; his lips on her forehead burn.

Darling, darling, darling. She knows the word for fondness, knows Ned means nothing by it, but she can’t help loathing it. The word has become a weapon, not in Ned’s mouth, not on purpose, but over the years it’s been a word to soothe, to dismiss, to hush. Her own name taken from her and turned against her—a gag, a chain. She would be happy never to hear it again.

With Ned still looking after her, and guilt dogging her steps, Wendy retreats to her room.

She allows herself a moment to sag, to feel the ache of Jane’s loss. As she does, a memory drops from nowhere, jarring and sharp. She’s running, her hand in Peter’s hand, the ground shaking, the earth bellowing.

It’s so real, so present, Wendy has to lean her weight against the post of her bed to remind herself she’s a grown woman in London. She isn’t a child, tagging along at Peter’s heels. There’s a lifetime of difference between who she was then and who she is now.

And yet over the years, in the quietest moments, she’s allowed herself the indulgence of remembering what it felt like to fly, to play follow the leader, to chase Peter along the twisting paths of Neverland’s forests. She wants that now, the purity, the simplicity, the freedom.

But this is something different. Not running for joy—running from something. Something terrible.

She can almost touch it. Her reaching fingers meet solid wood, a door, the memory locked away behind it. Something secret. Important.

She pushes it away. Now isn’t the time to think about what she’s lost. She needs to focus on what she has, how she will rescue Jane. Peter stole from her; she will steal from him in turn. She’s learned a great many things since he last saw her, and she will use every one of them against him to bring her daughter home.

Peter told her once that girls couldn’t go to war. Back then, she’d thought it terribly unfair, but he was right in a way. Wendy isn’t a soldier. She stayed home while her little brother went off to face guns and trenches, gas and grenades—but that doesn’t mean she isn’t a fighter. More than a fighter, she’s a survivor as well.

She survived St. Bernadette’s using the first skill that ever made her useful to Peter. That must count for something. As a child, her sewing was clumsy, but thanks to Mary’s patient instruction, she’s so much better now. Three years under Mary’s guidance with nothing else to do in that white-walled prison except practice making her stitches neat and tight.

Here, in the outside world, pockets are a convenience, a luxury; in the asylum, they were a necessity. Mary taught her to sew small, secret compartments into the hems and sleeves of her shapeless uniform, quick stitches strong enough to hold but easy enough to unpick so they wouldn’t be discovered in the laundry; invisible from the outside, tucked close against her skin. Sometimes merely touching them, even if they were empty, just knowing they were there, was enough to keep Wendy steady, anchoring her.

John had believed a private institution would mean better care. But Dr. Harrington had been the only full-time doctor in residence, and with less oversight, it was easy for the attendants to practice casual cruelty. Jamieson especially.

If Dr. Harrington’s attention was elsewhere, Jamieson would rally his fellow attendants against Wendy. They would trip her walking through the hallways, trying to loosen her temper, make her “hysterical,” so Dr. Harrington would prescribe bromides or have her locked in her room. There, they might “forget” to feed her, or her food would arrive with splinters or bits of broken glass tucked inside. And there were other things, too. Punishments she didn’t deserve. Torture.

But for every cruelty dealt to her, Wendy had retaliated. She stole unimportant things. Buttons. Shoelaces. Half a tin of loose tobacco leaf, a whole stack of rolling papers. Everything went into her secret pockets while she hid her smiles, watching the attendants grumble and search fruitlessly. Then she would return the stolen item days later, in a different place, making the attendants doubt their sanity the way they tried to make her doubt her own.

And never once was she caught. Those are the other skills St. Bernadette’s gave her. Stealth, silence, the ability to slip beneath notice. All she had to do was pretend to take her medicine. Be good, be calm. Remember. Lie. Pretend to forget.

But of course, she couldn’t forget. Peter had lodged beneath her skin like a splinter. Even at her lowest points—when she was tempted to give in and let go the way John and Michael did—she couldn’t dig him out. Peter was and is a part of her; Neverland is a part of her. The angled planes of Peter’s face, the fire of his hair, the gleam of his eyes—they are as familiar to her as her own features, as Ned’s, as Jane’s. She will use that to her advantage, too.

Even now Wendy can call to mind perfectly the innocence in Peter’s eyes the first night she met him. The way he held his shadow draped over his arms like the skin of some animal, hope lighting the planes of his face, asking her to make him whole. She’d taken the proffered shadow, silky and cool in her hands like the finest of fabrics, as if it was the most natural thing in the world. Of course a boy might become separated from his shadow, and of course a girl might sew it back on again.

At the time, she hadn’t thought it at all strange. Not even when, at the first touch of her needle, he’d shrieked as though she’d stuck him with a hot poker. Afterward, he’d gone around crowing and strutting as if he was the one who’d done something clever. As though Wendy had had no part in it at all, and she’d accepted that too.

By the time they’d arrived in Neverland, the shadow she’d stitched onto him had frayed and unraveled, withering like a rose cut from its vine. They’d landed on the beach in the harsh noonday sun and Peter had stood with his hands on his hips, the broken point at the center of a sundial. His Lost Boys had gathered in a circle around him to greet the Darling children, each trailing a shadow stark behind them on the white sand. Peter alone had cast none.

She should have known then, but all she’d seen was the promise of adventure, a boy who would teach her to fly.

Wendy kneels, retrieving her sewing box from beneath the bed. Needles, pins, spools of thread. Her little scissors, wicked and clever and bright. Sewing might not be a heroic skill, but it is hers. Simply carrying these things with her will calm and center her, a little piece of home in Neverland to remind her what she left behind, to remind her what it cost to visit there the first time.

Wendy closes her eyes, rests her hands on her thighs, and releases a breath. It’s still there, the connection between her and Peter, buried deep beneath her skin whether she wants him there or not. She spent years trying to shed herself of him, only to fail. Now she clings to that bond like a physical thread, binding the two of them. He can’t hide from her; she will follow that thread all the way back to Neverland.

Once invited, always welcome. Isn’t that his way?

NEVER, NEVER

A hush of sound, like running water, or a rolling storm. She turns her head toward the sound and finds her eyelids stuck shut. Has she been asleep? Dreaming? She dreamt of falling. No. Flying.

There’s a smell of growing things. It reminds her of Kensington Gardens. She used to walk there with her parents when she was very small, and now that she’s older, her father still takes her sometimes, looking for leaves and flowers and insects for her collections. Her favorite bit is the pond with its big white and gold fish coming to the surface to nibble at breadcrumbs, tails flashing and mouths making little ‘o’s.

Her thoughts drift, simultaneously heavy—sticky as her eyes—and light. She was just in the gardens, wasn’t she? Or she’s in the gardens now, reaching to catch one of the gold and white fish with her chubby fingers. No, that isn’t right. That happened years ago. She was four years old and she wanted to catch a fish to show her papa, but her mama snatched her hand away with a sharp “no!”.

“You must never reach into the water like that, _____, or you might fall in. It’s an important rule, just like you must never go away with strangers, and you must always stay where your papa and I can see you. Do you understand?”

She isn’t that small anymore, or foolish enough to need those lessons from her mother. Only she has gone away somewhere where her mama can’t see and there’s something wrong. There’s a humming blank in her memory where her name should be. If she thinks hard enough, she can see her mother’s lips move to shape the sound, but there’s nothing there. Only _____! How could she possibly have forgotten her own name?

She must know it, somewhere, only there’s something standing in the way. She tries to think it for herself, un-sticks her lips to shout it aloud, but what comes out instead is, “Mama!”

Her eyes fly open, painful, her lashes feeling like they’re tearing as they part wide. There was a boy. He took her hand, and they fell into the sky. Her body jerks in panic as though she’s falling again, but there’s a length of rope lying across her chest and legs, pinning her down. It’s heavy, damp, and smells of salt and the green weediness she mistook for fish ponds.

She tries to sit up, but her arms and legs are clumsy, flopping uselessly when she tries to push the rope away. Is she sick? Is that why she’s so weak? Maybe the boy at her window was only a fever dream.

Calm. She must be calm and take things one item at a time. Analyze her surroundings. That’s what a good scientist would do, and she does intend to be a scientist one day. That much she knows, even if she can’t remember her own name. She breathes in, focusing on what information she can gather while lying still.

The ground beneath her is faintly damp and it gives strangely beneath her. This certainly isn’t her bedroom. None of her things are here—the globe her papa gave her on her last birthday, the magnifying glass she uses to see the delicate scales of butterfly wings and the veins in her leaves.

Her mama warned her about going away with strangers, but she didn’t. Not on purpose. Tightness rises in her chest, making it hard to breathe, threatening her with tears.

The sound of her involuntary, hitching breath makes her angry, and she pushes the fear down as hard as she can. Panic won’t do. She must be rational. Assess her situation, look for clues.

She turns her attention straight up, easy enough since she’s already on her back. Light filters through branches laid together haphazardly, making a shelter. They’re balanced against something solid. She’s able to tilt her head back just far enough to see the curving bulk of a wooden construction, but she isn’t able to make out the whole.

The harsh laughter of gulls calling to each other clarifies the sound of water. It’s the steady hush of waves. She must be on a beach. But how is that possible? Her parents would have told her if they were planning a holiday, and certainly they wouldn’t have spirited her away in the middle of the night. She would have packed appropriately, bringing her nets and collecting jars. And there’s still the boy, and her mother reaching after her. She certainly isn’t on holiday, and something is very wrong.

Applying a burst of effort, she rolls onto her side, the coils of rope slithering free, not even tying her down, just piled haphazardly as if someone meant to bind her then forgot. She sits up, twisting around so she can see that the curve of wood holding up the branches is the hull of a ship. The sand beneath her is wet, the dampness soaking through her nightgown, leaving her cold.

“Wendy! You’re awake!” The branches rustle and the boy from her window pokes his head through them, grinning.

Wendy. That’s her mother’s name. And she’s… Jane. The name is suddenly there, like something emerging from the fog, still half obscured so she isn’t certain it truly is familiar after all. Is it her? Her thoughts move slowly, like the long strings of almost-burnt sugar Cook pulls into caramel. She helps Cook in the kitchen sometimes. The precision of the measurements please her, and the way slight variations can produce different results is just like a scientific experiment. But even better, at the end, patient stirring is rewarded with a taste test.

She can almost feel the smoky sweetness on her tongue, the mass of candy clinging to her back teeth. She shakes her head, a sharp motion, bringing her thoughts back to the here and now. She isn’t normally the flighty sort; she’s a very sensible girl, her mother and father have often told her so. Right now, though, her head feels thick and muzzy, and it’s hard to concentrate.

“Who are you?” She presses her back against the ship, drawing her knees up and wrapping her arms around them.