PREFACE.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

HORRIBLE LONDON.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER I.

I

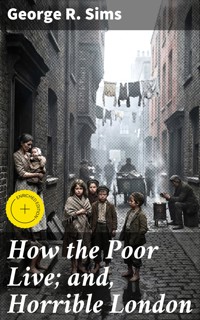

commence, with the first of these chapters, a book of travel. An

author and an artist have gone hand-in-hand into many a far-off

region of the earth, and the result has been a volume eagerly studied

by the stay-at-home public, anxious to know something of the world in

which they live. In these pages I propose to record the result of a

journey into a region which lies at our own doors—into a dark

continent that is within easy walking distance of the General Post

Office. This continent will, I hope, be found as interesting as any

of those newly-explored lands which engage the attention of the Royal

Geographical Society—the wild races who inhabit it will, I trust,

gain public sympathy as easily as those savage tribes for whose

benefit the Missionary Societies never cease to appeal for funds.I

have no shipwrecks, no battles, no moving adventures by flood and

field, to record. Such perils as I and my fellow-traveller have

encountered on our journey are not of the order which lend themselves

to stirring narrative. It is unpleasant to be mistaken, in

underground cellars where the vilest outcasts hide from the light of

day, for detectives in search of their prey—it is dangerous to

breathe for some hours at a stretch an atmosphere charged with

infection and poisoned with indescribable effluvia—it is hazardous

to be hemmed in down a blind alley by a crowd of roughs who have had

hereditarily transmitted to them the maxim of John Leech, that

half-bricks were specially designed for the benefit of 'strangers;'

but these are not adventures of the heroic order, and they will not

be dwelt upon lovingly after the manner of travellers who go farther

afield.My

task is perhaps too serious a one even for the light tone of these

remarks. No man who has seen 'How the Poor Live' can return from the

journey with aught but an aching heart. No man who recognises how

serious is the social problem which lies before us can approach its

consideration in any but the gravest mood. Let me, then, briefly

place before the reader the serious purpose of these pages, and then

I will ask him to set out with me on the journey and judge for

himself whether there is no remedy for much that he will see. He will

have to encounter misery that some good people think it best to leave

undiscovered. He will be brought face to face with that dark side of

life which the wearers of rose-coloured spectacles turn away from on

principle. The worship of the beautiful is an excellent thing, but he

who digs down deep in the mire to find the soul of goodness in things

evil is a better man and a better Christian than he who shudders at

the ugly and the unclean, and kicks it from his path, that it may not

come between the wind and his nobility.But

let not the reader be alarmed, and imagine that I am about to take

advantage of his good-nature in order to plunge him neck-high into a

mud bath. He may be pained before we part company, but he shall not

be disgusted. He may occasionally feel a choking in his throat, but

he shall smile now and again. Among the poor there is humour as well

as pathos, there is food for laughter as well as for tears, and the

rays of God's sunshine lose their way now and again, and bring light

and gladness into the vilest of the London slums.His

Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, in his speech at the opening of

the Royal College of Music some years ago, said: 'The time has come

when class can no longer stand aloof from class, and that man does

his duty best who works most earnestly in bridging over the gulf

between different classes which it is the tendency of increased

wealth and increased civilization to widen.' It is to increased

wealth and to increased civilization that we owe the wide gulf which

to-day separates well-to-do citizens from the masses. It is the

increased wealth of this mighty city which has driven the poor back

inch by inch, until we find them to-day herding together, packed like

herrings in a barrel, neglected and despised, and left to endure

wrongs and hardships which, if they were related of a far-off savage

tribe, would cause Exeter Hall to shudder till its bricks fell down.

It is the increased civilization of this marvellous age which has

made life a victory only for the strong, the gifted, and the

specially blest, and left the weak, the poor, and the ignorant to

work out in their proper persons the theory of the survival of the

fittest to its bitter end.There

are not wanting signs that the 'one-roomed helot' and his brood are

about to receive a little scientific attention. They have become

natural curiosities, and to this fact they may owe the honour in

store for them, of dividing public attention with the Zenanas, the

Aborigines, and the South Sea Islanders. The long-promised era of

domestic legislation is said to be at hand, and prophets with

powerful telescopes declare they can see the first faint signs of its

dawn upon the political horizon. When that era has come within the

range of the naked eye, it is probable that the Homes of the Poor

will be one of its burning questions, and the strong arm of the law

may be extended protectingly, even at the risk of showing the

shortness of its sleeve, as far as the humble toilers who at the

present moment suffer only its penalties and enjoy none of its

advantages.That

there are remedies for the great evil which lies like a cankerworm in

the heart of this fair city is certain. What those remedies are you

will be better able to judge when you have seen the condition of the

disease for which Dr. State is to be called in. Dr. State, alas! is

as slow to put in an appearance as his parish

confrère when the

patient in need of his services is poor and friendless.Forgive

me this little discourse by the way. It has at any rate filled up the

time as we walk along to the outskirts of the land through which we

are to travel for a few weeks together. And now, turning out of the

busy street alive with the roar of commerce, and where the great

marts and warehouses tower stories high, and where Dives adds daily

to his wealth, we turn up a narrow court, and find ourselves at once

in the slum where Lazarus lays his head—even as he did in the

sacred story—at the very gates of the mighty millionaire.We

walk along a narrow dirty passage, which would effectually have

stopped the Claimant had he come to this neighbourhood in search of

witnesses, and at the end we find ourselves in what we should call a

back-yard, but which, in the language of the neighbourhood, is a

square. The square is full of refuse; heaps of dust and decaying

vegetable matter lie about here and there, under the windows and in

front of the doors of the squalid tumble-down houses. The windows

above and below are broken and patched; the roofs of these

two-storied 'eligible residences' look as though Lord Alcester had

been having some preliminary practice with his guns here before he

set sail for Alexandria. All these places are let out in single rooms

at prices varying from 2s. 6d to 4s. a week. We can see a good deal

of the inside through the cracks and crevices and broken panes, but

if we knock at the door we shall get a view of the inhabitants.If

you knew more of these Alsatias, you would be rather astonished that

there was a door to knock at. Most of the houses are open day and

night, and knockers and bells are things unknown. Here, however, the

former luxuries exist; so we will not disdain them.Knock,

knock!Hey,

presto! what a change of scene! Sleepy Hollow has come to life. Every

door flies open, and there is a cluster of human beings on the

threshold. Heads of matted hair and faces that haven't seen soap for

months come out of the broken windows above.Our

knock has alarmed the neighbourhood. Who are we? The police? No. Who

are we? Now they recognise one of our number—our guide—with a

growl. He and we with him can pass without let or hindrance where it

would be dangerous for a policeman to go. We are supposed to be on

business connected with the School Board, and we are armed with a

password which the worst of these outcasts have grown at last sulkily

to acknowledge.This

is a very respectable place, and we have taken it first to break the

ground gently for an artist who has not hitherto studied 'character'

on ground where I have had many wanderings.To

the particular door attacked there comes a poor woman, white and thin

and sickly-looking; in her arms she carries a girl of eight or nine

with a diseased spine; behind her, clutching at her scanty dress, are

two or three other children. We put a statistical question, say a

kind word to the little ones, and ask to see the room.What

a room! The poor woman apologizes for its condition, but the helpless

child, always needing her care, and the other little ones to look

after, and times being bad, etc. Poor creature, if she had ten pair

of hands instead of one pair always full, she could not keep this

room clean. The walls are damp and crumbling, the ceiling is black

and peeling off, showing the laths above, the floor is rotten and

broken away in places, and the wind and the rain sweep in through

gaps that seem everywhere. The woman, her husband, and her six

children live, eat, and sleep in this one room, and for this they pay

three shillings a week. It is quite as much as they can afford. There

has been no breakfast yet, and there won't be any till the husband

(who has been out to try and get a job) comes in and reports

progress. As to complaining of the dilapidated, filthy condition of

the room, they know better. If they don't like it they can go. There

are dozens of families who will jump at the accommodation, and the

landlord is well aware of the fact.Some

landlords do repair their tenants' rooms. Why, cert'nly. Here is a

sketch of one and of the repairs we saw the same day. Rent, 4s. a

week; condition indescribable. But notice the repairs: a bit of a

box-lid nailed across a hole in the wall big enough for a man's head

to go through, a nail knocked into a window-frame beneath which still

comes in a little fresh air, and a strip of new paper on a corner of

the wall. You can't see the new paper because it is not up. The lady

of the rooms holds it in her hand. The rent collector has just left

it for her to put up herself. Its value, at a rough guess, is

threepence. This landlord

has executed

repairs. Items: one piece of a broken soap-box, one yard and a half

of paper, and one nail.

And for these repairs he has raised the rent of the room threepence a

week.We

are not in the square now, but in a long dirty street, full of

lodging-houses from end to end, a perfect human warren, where every

door stands open night and day—a state of things that shall be

described and illustrated a little later on when we come to the

''appy dossers.' In this street, close to the repaired residence, we

select at hazard an open doorway and plunge into it. We pass along a

greasy, grimy passage, and turn a corner to ascend the stairs. Round

the corner it is dark. There is no staircase light, and we can hardly

distinguish in the gloom where we are going. A stumble causes us to

strike a light.That

stumble was a lucky one. The staircase we were ascending, and which

men and women and little children go up and down day after day and

night after night, is a wonderful affair. The handrail is broken

away, the stairs themselves are going—a heavy boot has been clean

through one of them already, and it would need very little, one would

think, for the whole lot to give way and fall with a crash. A sketch,

taken at the time, by the light of successive vestas, fails to give

the grim horror of that awful staircase. The surroundings, the ruin,

the decay, and the dirt, could not be reproduced.We

are anxious to see what kind of people get safely up and down this

staircase, and as we ascend we knock accidentally up against

something; it is a door and a landing. The door is opened, and as the

light is thrown on to where we stand we give an involuntary

exclamation of horror; the door opens right on to the corner stair.

The woman who comes out would, if she stepped incautiously, fall six

feet, and nothing could save her. It is a tidy room this, for the

neighbourhood. A good hardworking woman has kept her home neat, even

in such surroundings. The rent is four and sixpence a week, and the

family living in it numbers eight souls; their total earnings are

twelve shillings. A hard lot, one would fancy; but in comparison to

what we have to encounter presently it certainly is not. Asked about

the stairs, the woman says, 'It is a little ockard-like for the

young'uns a-goin' up and down to school now the Board make'em wear

boots; but they don't often hurt themselves.' Minus the boots, the

children had got used to the ascent and descent, I suppose, and were

as much at home on the crazy staircase as a chamois on a precipice.

Excelsior is our

motto on this staircase. No maiden with blue eyes comes out to

mention avalanches, but the woman herself suggests 'it's werry bad

higher up.' We are as heedless of the warning as Longfellow's

headstrong banner-bearer, for we go on.It

is 'werry bad' higher up, so bad that we begin to light some more

matches and look round to see how we are to get down. But as we

continue to ascend the darkness grows less and less. We go a step at

a time, slowly and circumspectly, up, up to the light, and at last

our heads are suddenly above a floor and looking straight into a

room.We

have reached the attic, and in that attic we see a picture which will

be engraven on our memory for many a month to come.The

attic is almost bare; in a broken fireplace are some smouldering

embers; a log of wood lies in front like a fender. There is a broken

chair trying to steady itself against a wall black with the dirt of

ages. In one corner, on a shelf, is a battered saucepan and a piece

of dry bread. On the scrap of mantel still remaining embedded in the

wall is a rag; on a bit of cord hung across the room are more

rags—garments of some sort, possibly; a broken flower-pot props

open a crazy window-frame, possibly to let the smoke out, or

in—looking at the chimney-pots below, it is difficult to say which;

and at one side of the room is a sack of Heaven knows what—it is a

dirty, filthy sack, greasy and black and evil-looking. I could not

guess what was in it if I tried, but what was on it was a little

child—a neglected, ragged, grimed, and bare-legged little baby-girl

of four. There she sat, in the bare, squalid room, perched on the

sack, erect, motionless, expressionless, on duty.She

was 'a little sentinel,' left to guard a baby that lay asleep on the

bare boards behind her, its head on its arm, the ragged remains of

what had been a shawl flung over its legs.That

baby needed a sentinel to guard it, indeed. Had it crawled a foot or

two, it would have fallen head-foremost into that unprotected,

yawning abyss of blackness below. In case of some such proceeding on

its part, the child of four had been left 'on guard.'The

furniture of the attic, whatever it was like, had been seized the

week before for rent. The little sentinel's papa—this we unearthed

of the 'deputy' of the house later on—was a militiaman, and away;

the little sentinel's mamma was gone out on 'a arrand,' which, if it

was anything like her usual 'arrands,' the deputy below informed us,

would bring her home about dark, very much the worse for it. Think of

that little child keeping guard on that dirty sack for six or eight

hours at a stretch—think of her utter loneliness in that bare,

desolate room, every childish impulse checked, left with orders 'not

to move, or I'll kill yer,' and sitting there often till night and

darkness came on, hungry, thirsty, and tired herself, but faithful to

her trust to the last minute of the drunken mother's absence! 'Bless

yer! I've known that young'un sit there eight 'our at a stretch. I've

seen her there of a mornin' when I've come up to see if I could git

the rint, and I've seen her there when I've come agin at night,' says

the deputy. 'Lor, that ain't nothing—that ain't.'Nothing!

It is one of the saddest pictures I have seen for many a day. Poor

little baby-sentinel!—left with a human life in its sole charge at

four—neglected and overlooked: what will its girl-life be, when it

grows old enough to think? I should like some of the little ones

whose every wish is gratified, who have but to whimper to have, and

who live surrounded by loving, smiling faces, and tendered by gentle

hands, to see the little child in the bare garret sitting sentinel

over the sleeping baby on the floor, and budging never an inch

throughout the weary day from the place that her mother had bidden

her stay in.With

our minds full of this pathetic picture of child-life in the 'Homes

of the Poor,' we descend the crazy staircase, and get out into as

much light as can find its way down these narrow alleys.Outside

we see a portly gentleman with a big gold chain across his capacious

form, and an air of wealth and good living all over him. He is the

owner of a whole block of property such as this, and he waxes rich on

his rents. Strange as it may seem, these one-roomed outcasts are the

best paying tenants in London. They pay so much for so little, and

almost fight to get it. That they should be left to be thus exploited

is a disgrace to the Legislature, which is never tired of protecting

the oppressed of 'all races that on earth do dwell,' except those of

that particular race who have the honour to be free-born Englishmen.

CHAPTER II.

As I glance over the notes I have jotted down

during my journey through Outcasts' Land, the delicacy of the task

I have undertaken comes home to me more forcibly than ever. The

housing of the poor and the remedy for the existing state of things

are matters I have so much at heart, that I fear lest I should not

make ample use of the golden opportunities here afforded me of

ventilating the subject. On the other hand, I hesitate to repel the

reader, and, unfortunately, the best illustrations of the evils of

overcrowding are repulsive to a degree.

Perhaps if I hint at a few of

the very bad cases, it will be sufficient. Men and women of the

world will be able to supply the details and draw the correct

deductions; and it is, after all, only men and women of the world

whose practical sympathy is likely to be enlisted by a revelation

of the truth about the poor of great cities.

Come with me down this court,

where at eleven o'clock in the morning a dead silence reigns. Every

house is tenanted, but the blinds of the windows are down and the

doors are shut. Blinds and doors! Yes, these luxuries are visible

here. This is an aristocratic street, and the rents are paid

regularly. There is no grinding poverty, no starvation here, and no

large families to drag at the bread-winner. There is hardly any

child-life here at all, for the men are thieves and highway cheats,

and the women are of the class which has furnished the companions

of such men from the earliest annals of roguedom.

The colony sleeps though the

sun is high. The day with them is the idle time, and they reap

their harvest in the hours of darkness. Later in the day, towards

two o'clock, there will be signs of life; oaths and shouts will

issue from the now silent rooms, and there will be fierce wrangles

and fights over the division of ill-gotten gains. The spirit of

murder hovers over this spot, for life is held of little account.

There is a Bill Sikes and Nancy in scores of these tenements, and

the brutal blow is ever the accompaniment of the brutal

oath.

These people, remember, rub

elbows with the honest labouring poor; their lives are no mystery

to the boys and girls in the neighbourhood; the little girls often

fetch Nancy's gin, and stand in a gaping crowd while Nancy and Bill

exchange compliments on the doorstep, drawn from the well of Saxon,

impure and utterly defiled. The little boys look up half with awe

and half with admiration at the burly Sikes with his flash style,

and delight in gossip concerning his talents as a 'crib-cracker,'

and his adventures as a pickpocket: The poor—the honest poor—have

been driven by the working of the Artizans' Dwellings Acts, and the

clearance of rookery after rookery, to come and herd with thieves

and wantons, to bring up their children in the last Alsatias, where

lawlessness and violence still reign supreme.

The constant association of the

poor and the criminal class has deadened in the former nearly all

sense of right and wrong. In the words of one of them, 'they can't

afford to be particular about their choice of neighbours.' I was

but the other day in a room in this district occupied by a widow

woman, her daughters of seventeen and sixteen, her sons of fourteen

and thirteen, and two younger children. Her wretched apartment was

on the street level, and behind it was the common yard of the

tenement. In this yard the previous night a drunken sailor had been

desperately maltreated, and left for dead. I asked the woman if she

had not heard the noise, and why she didn't interfere. 'Heard it?'

was the reply; 'well, we ain't deaf, but they're a rum lot in this

here house, and we're used to rows. There ain't a night passes as

there ain't a fight in the passage or a drunken row; but why should

I interfere?'Taint no business of mine.' As a matter of fact, this

woman, her grown-up daughters, and her boys must have lain in that

room night after night, hearing the most obscene language, having a

perfect knowledge of the proceedings of the vilest and most

depraved of profligate men and women forced upon them, hearing

cries of murder and the sound of blows, knowing that almost every

crime in the Decalogue was being committed in that awful back yard

on which that broken casement looked, and yet not one of them had

ever dreamed of stirring hand or foot. They were saturated with the

spirit of the place, and though they were respectable people

themselves, they saw nothing criminal in the behaviour of their

neighbours.

For this room, with its

advantages, the widow paid four and sixpence a week; the walls were

mildewed and streaming with damp; the boards as you trod upon them

made the slushing noise of a plank spread across a mud puddle in a

brickfield; foul within and foul without, these people paid the

rent of it gladly, and perhaps thanked God for the luck of having

it. Rooms for the poor earning precarious livelihoods are too hard

to get and too much in demand now for a widow woman to give up one

just because of the trifling inconvenience of overhearing a few

outrages and murders.

One word more on this shady

subject and we will get out into the light again. I have spoken of

the familiarity of the children of the poor with all manner of

wickedness and crime. Of all the evils arising from this one-room

system there is perhaps none greater than the utter destruction of

innocence in the young. A moment's thought will enable the reader

to appreciate the evils of it. But if it is bad in the case of a

respectable family, how much more terrible is it when the children

are familiarized with actual immorality!

Wait outside while we knock at

this door.

Knock, knock!—No

answer!

Knock, knock, knock!

A child's voice answers, 'What

is it?'

We give the answer—the answer

which has been our 'open, sesame' everywhere—and after a pause a

woman opens a door a little and asks us to wait a moment. Presently

we are admitted. A woman pleasing looking and with a certain

refinement in her features holds the door open for us. She has

evidently made a hurried toilet and put on an ulster over her night

attire. She has also put a brass chain and locket round her neck.

There is a little rouge left on her cheeks and a little of the

burnt hairpin colour left under her eyes from overnight. At the

table having their breakfast are two neat and clean little girls of

seven and eight.

They rise and curtsey as we

enter. We ask them a few questions, and they answer

intelligently—they are at the Board School and are making admirable

progress—charming children, interesting and well-behaved in every

way. They have a perfect knowledge of good and evil—one of them has

taken a Scripture prize—and yet these two charming and intelligent

little girls live in that room night and day with their mother, and

this is the den to which she snares her dissolute prey.

I would gladly have passed over

this scene in silence, but it is one part of the question which

directly bears on the theory of State interference. It is by

shutting our eyes to evils that we allow them to continue

unreformed so long. I maintain that such cases as these are fit

ones for legislative protection. The State should have the power of

rescuing its future citizens from such surroundings, and the law

which protects young children from physical hurt should also be so

framed as to shield them from moral destruction.

The worst effect of the present

system of Packing the Poor is the moral destruction of the next

generation.

Whatever it costs us to remedy

the disease we shall gain in decreased crime and wickedness. It is

better even that the ratepayers should bear a portion of the

burthen of new homes for the respectable poor than that they should

have to pay twice as much in the long-run for prisons, lunatic

asylums, and workhouses.

Enough for the present of the

criminal classes. Let us see some of the poor people who earn an

honest living—well, 'living,' perhaps, is hardly the word—let us

say, who can earn enough to pay their rent and keep body and soul

together.

Here is a quaint scene, to

begin with. When we open the door we start back half choked. The

air is full of floating fluff, and some of it gets into our mouths

and half chokes us. When we've coughed and wheezed a little we look

about us and gradually take in the situation.

The room is about eight feet

square. Seated on the floor is a white fairy—a dark-eyed girl who

looks as though she had stepped straight off a twelfth cake. Her

hair is powdered all overa la

Pompadour, and the effect isbizarre. Seated beside her is an older

woman, and she is white and twelfth-cakey too. Alas! their

occupation is prosaic to a degree. They are simply pulling

rabbit-skins—that is to say, they are pulling away all the loose

fluff and down and preparing the skins for the furriers, who will

use them for cheap goods, dye them into imitations of rarer skins,

and practise up [...]