0,49 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

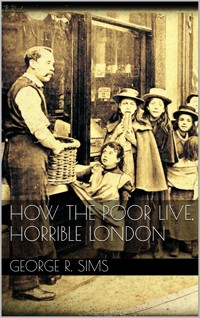

In "How the Poor Live; and, Horrible London," George R. Sims delves into the stark realities of poverty in Victorian London, employing a vivid, journalistic style that blends narrative storytelling with acute social critique. The book vividly illustrates the harrowing conditions faced by the urban poor, from overcrowded slums to the pervasive despair marked by disease and destitution. Sims'Äôs prose is both poetic and unflinching, providing readers with a candid portrayal of a society grappling with its moral obligations towards its most vulnerable citizens. Contextually, this work emerges from the era's burgeoning social awareness and reform movements, placing it within the broader discourse on social justice during the late 19th century. George R. Sims was not only a playwright but also a journalist and social reformer, deeply influenced by the stark disparities he observed around him. His commitment to illuminating the plight of the impoverished can be traced to his own experiences and the growing social consciousness of his time, which prompted him to advocate for change through his writing. Sims's narrative authority comes from his intimate understanding of London's social fabric, which he dissected with compassion and critique. I highly recommend "How the Poor Live; and, Horrible London" to readers interested in social history, literature, and the conditions of urban life during the Victorian era. Sims's poignant observations remain relevant, resonating with contemporary discussions about inequality and societal responsibility, making this work essential for anyone seeking to understand the complexities of human suffering and resilience.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

How the Poor Live; and, Horrible London

Table of Contents

Original

PREFACE.

The papers which form this volume appeared originally in The Pictorial World and The Daily News. The interest now evinced in the great question of Housing the Poor leads me to hope that they will be of assistance to many who are studying the subject, and would desire to have their information in a convenient form for reference. Much that I ventured to prognosticate when 'How the Poor Live' was written has happened since, and I have the permission of the author of 'The Bitter Cry of Outcast London' to say that from these articles he derived the greatest assistance while compiling his famous pamphlet. I have thought it well, all circumstances considered, to let the work stand in its original form, and have in no way added to it or altered it.

If an occasional lightness of treatment seems to the reader out of harmony with so grave a subject, I pray that he will remember the work was undertaken to enlist the sympathies of a class not generally given to the study of 'low life.'

GEORGE R. SIMS

HOW THE POOR LIVE.

CHAPTER I.

I commence, with the first of these chapters, a book of travel. An author and an artist have gone hand-in-hand into many a far-off region of the earth, and the result has been a volume eagerly studied by the stay-at-home public, anxious to know something of the world in which they live. In these pages I propose to record the result of a journey into a region which lies at our own doors—into a dark continent that is within easy walking distance of the General Post Office. This continent will, I hope, be found as interesting as any of those newly-explored lands which engage the attention of the Royal Geographical Society—the wild races who inhabit it will, I trust, gain public sympathy as easily as those savage tribes for whose benefit the Missionary Societies never cease to appeal for funds.

I have no shipwrecks, no battles, no moving adventures by flood and field, to record. Such perils as I and my fellow-traveller have encountered on our journey are not of the order which lend themselves to stirring narrative. It is unpleasant to be mistaken, in underground cellars where the vilest outcasts hide from the light of day, for detectives in search of their prey—it is dangerous to breathe for some hours at a stretch an atmosphere charged with infection and poisoned with indescribable effluvia—it is hazardous to be hemmed in down a blind alley by a crowd of roughs who have had hereditarily transmitted to them the maxim of John Leech, that half-bricks were specially designed for the benefit of 'strangers;' but these are not adventures of the heroic order, and they will not be dwelt upon lovingly after the manner of travellers who go farther afield.

My task is perhaps too serious a one even for the light tone of these remarks. No man who has seen 'How the Poor Live' can return from the journey with aught but an aching heart. No man who recognises how serious is the social problem which lies before us can approach its consideration in any but the gravest mood. Let me, then, briefly place before the reader the serious purpose of these pages, and then I will ask him to set out with me on the journey and judge for himself whether there is no remedy for much that he will see. He will have to encounter misery that some good people think it best to leave undiscovered. He will be brought face to face with that dark side of life which the wearers of rose-coloured spectacles turn away from on principle. The worship of the beautiful is an excellent thing, but he who digs down deep in the mire to find the soul of goodness in things evil is a better man and a better Christian than he who shudders at the ugly and the unclean, and kicks it from his path, that it may not come between the wind and his nobility.

But let not the reader be alarmed, and imagine that I am about to take advantage of his good-nature in order to plunge him neck-high into a mud bath. He may be pained before we part company, but he shall not be disgusted. He may occasionally feel a choking in his throat, but he shall smile now and again. Among the poor there is humour as well as pathos, there is food for laughter as well as for tears, and the rays of God's sunshine lose their way now and again, and bring light and gladness into the vilest of the London slums.

His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, in his speech at the opening of the Royal College of Music some years ago, said: 'The time has come when class can no longer stand aloof from class, and that man does his duty best who works most earnestly in bridging over the gulf between different classes which it is the tendency of increased wealth and increased civilization to widen.' It is to increased wealth and to increased civilization that we owe the wide gulf which to-day separates well-to-do citizens from the masses. It is the increased wealth of this mighty city which has driven the poor back inch by inch, until we find them to-day herding together, packed like herrings in a barrel, neglected and despised, and left to endure wrongs and hardships which, if they were related of a far-off savage tribe, would cause Exeter Hall to shudder till its bricks fell down. It is the increased civilization of this marvellous age which has made life a victory only for the strong, the gifted, and the specially blest, and left the weak, the poor, and the ignorant to work out in their proper persons the theory of the survival of the fittest to its bitter end.

There are not wanting signs that the 'one-roomed helot' and his brood are about to receive a little scientific attention. They have become natural curiosities, and to this fact they may owe the honour in store for them, of dividing public attention with the Zenanas, the Aborigines, and the South Sea Islanders. The long-promised era of domestic legislation is said to be at hand, and prophets with powerful telescopes declare they can see the first faint signs of its dawn upon the political horizon. When that era has come within the range of the naked eye, it is probable that the Homes of the Poor will be one of its burning questions, and the strong arm of the law may be extended protectingly, even at the risk of showing the shortness of its sleeve, as far as the humble toilers who at the present moment suffer only its penalties and enjoy none of its advantages.

That there are remedies for the great evil which lies like a cankerworm in the heart of this fair city is certain. What those remedies are you will be better able to judge when you have seen the condition of the disease for which Dr. State is to be called in. Dr. State, alas! is as slow to put in an appearance as his parish confrère when the patient in need of his services is poor and friendless.

Forgive me this little discourse by the way. It has at any rate filled up the time as we walk along to the outskirts of the land through which we are to travel for a few weeks together. And now, turning out of the busy street alive with the roar of commerce, and where the great marts and warehouses tower stories high, and where Dives adds daily to his wealth, we turn up a narrow court, and find ourselves at once in the slum where Lazarus lays his head—even as he did in the sacred story—at the very gates of the mighty millionaire.

We walk along a narrow dirty passage, which would effectually have stopped the Claimant had he come to this neighbourhood in search of witnesses, and at the end we find ourselves in what we should call a back-yard, but which, in the language of the neighbourhood, is a square. The square is full of refuse; heaps of dust and decaying vegetable matter lie about here and there, under the windows and in front of the doors of the squalid tumble-down houses. The windows above and below are broken and patched; the roofs of these two-storied 'eligible residences' look as though Lord Alcester had been having some preliminary practice with his guns here before he set sail for Alexandria. All these places are let out in single rooms at prices varying from 2s. 6d to 4s. a week. We can see a good deal of the inside through the cracks and crevices and broken panes, but if we knock at the door we shall get a view of the inhabitants.

If you knew more of these Alsatias, you would be rather astonished that there was a door to knock at. Most of the houses are open day and night, and knockers and bells are things unknown. Here, however, the former luxuries exist; so we will not disdain them.

Knock, knock!

Hey, presto! what a change of scene! Sleepy Hollow has come to life. Every door flies open, and there is a cluster of human beings on the threshold. Heads of matted hair and faces that haven't seen soap for months come out of the broken windows above.

Our knock has alarmed the neighbourhood. Who are we? The police? No. Who are we? Now they recognise one of our number—our guide—with a growl. He and we with him can pass without let or hindrance where it would be dangerous for a policeman to go. We are supposed to be on business connected with the School Board, and we are armed with a password which the worst of these outcasts have grown at last sulkily to acknowledge.

This is a very respectable place, and we have taken it first to break the ground gently for an artist who has not hitherto studied 'character' on ground where I have had many wanderings.

To the particular door attacked there comes a poor woman, white and thin and sickly-looking; in her arms she carries a girl of eight or nine with a diseased spine; behind her, clutching at her scanty dress, are two or three other children. We put a statistical question, say a kind word to the little ones, and ask to see the room.

What a room! The poor woman apologizes for its condition, but the helpless child, always needing her care, and the other little ones to look after, and times being bad, etc. Poor creature, if she had ten pair of hands instead of one pair always full, she could not keep this room clean. The walls are damp and crumbling, the ceiling is black and peeling off, showing the laths above, the floor is rotten and broken away in places, and the wind and the rain sweep in through gaps that seem everywhere. The woman, her husband, and her six children live, eat, and sleep in this one room, and for this they pay three shillings a week. It is quite as much as they can afford. There has been no breakfast yet, and there won't be any till the husband (who has been out to try and get a job) comes in and reports progress. As to complaining of the dilapidated, filthy condition of the room, they know better. If they don't like it they can go. There are dozens of families who will jump at the accommodation, and the landlord is well aware of the fact.

Some landlords do repair their tenants' rooms. Why, cert'nly. Here is a sketch of one and of the repairs we saw the same day. Rent, 4s. a week; condition indescribable. But notice the repairs: a bit of a box-lid nailed across a hole in the wall big enough for a man's head to go through, a nail knocked into a window-frame beneath which still comes in a little fresh air, and a strip of new paper on a corner of the wall. You can't see the new paper because it is not up. The lady of the rooms holds it in her hand. The rent collector has just left it for her to put up herself. Its value, at a rough guess, is threepence. This landlord has executed repairs. Items: one piece of a broken soap-box, one yard and a half of paper, and one nail. And for these repairs he has raised the rent of the room threepence a week.

We are not in the square now, but in a long dirty street, full of lodging-houses from end to end, a perfect human warren, where every door stands open night and day—a state of things that shall be described and illustrated a little later on when we come to the ''appy dossers.' In this street, close to the repaired residence, we select at hazard an open doorway and plunge into it. We pass along a greasy, grimy passage, and turn a corner to ascend the stairs. Round the corner it is dark. There is no staircase light, and we can hardly distinguish in the gloom where we are going. A stumble causes us to strike a light.

That stumble was a lucky one. The staircase we were ascending, and which men and women and little children go up and down day after day and night after night, is a wonderful affair. The handrail is broken away, the stairs themselves are going—a heavy boot has been clean through one of them already, and it would need very little, one would think, for the whole lot to give way and fall with a crash. A sketch, taken at the time, by the light of successive vestas, fails to give the grim horror of that awful staircase. The surroundings, the ruin, the decay, and the dirt, could not be reproduced.

We are anxious to see what kind of people get safely up and down this staircase, and as we ascend we knock accidentally up against something; it is a door and a landing. The door is opened, and as the light is thrown on to where we stand we give an involuntary exclamation of horror; the door opens right on to the corner stair. The woman who comes out would, if she stepped incautiously, fall six feet, and nothing could save her. It is a tidy room this, for the neighbourhood. A good hardworking woman has kept her home neat, even in such surroundings. The rent is four and sixpence a week, and the family living in it numbers eight souls; their total earnings are twelve shillings. A hard lot, one would fancy; but in comparison to what we have to encounter presently it certainly is not. Asked about the stairs, the woman says, 'It is a little ockard-like for the young 'uns a-goin' up and down to school now the Board make 'em wear boots; but they don't often hurt themselves.' Minus the boots, the children had got used to the ascent and descent, I suppose, and were as much at home on the crazy staircase as a chamois on a precipice. Excelsior is our motto on this staircase. No maiden with blue eyes comes out to mention avalanches, but the woman herself suggests 'it's werry bad higher up.' We are as heedless of the warning as Longfellow's headstrong banner-bearer, for we go on.

It is 'werry bad' higher up, so bad that we begin to light some more matches and look round to see how we are to get down. But as we continue to ascend the darkness grows less and less. We go a step at a time, slowly and circumspectly, up, up to the light, and at last our heads are suddenly above a floor and looking straight into a room.

We have reached the attic, and in that attic we see a picture which will be engraven on our memory for many a month to come.

The attic is almost bare; in a broken fireplace are some smouldering embers; a log of wood lies in front like a fender. There is a broken chair trying to steady itself against a wall black with the dirt of ages. In one corner, on a shelf, is a battered saucepan and a piece of dry bread. On the scrap of mantel still remaining embedded in the wall is a rag; on a bit of cord hung across the room are more rags—garments of some sort, possibly; a broken flower-pot props open a crazy window-frame, possibly to let the smoke out, or in—looking at the chimney-pots below, it is difficult to say which; and at one side of the room is a sack of Heaven knows what—it is a dirty, filthy sack, greasy and black and evil-looking. I could not guess what was in it if I tried, but what was on it was a little child—a neglected, ragged, grimed, and bare-legged little baby-girl of four. There she sat, in the bare, squalid room, perched on the sack, erect, motionless, expressionless, on duty.

She was 'a little sentinel,' left to guard a baby that lay asleep on the bare boards behind her, its head on its arm, the ragged remains of what had been a shawl flung over its legs.

That baby needed a sentinel to guard it, indeed. Had it crawled a foot or two, it would have fallen head-foremost into that unprotected, yawning abyss of blackness below. In case of some such proceeding on its part, the child of four had been left 'on guard.'

The furniture of the attic, whatever it was like, had been seized the week before for rent. The little sentinel's papa—this we unearthed of the 'deputy' of the house later on—was a militiaman, and away; the little sentinel's mamma was gone out on 'a arrand,' which, if it was anything like her usual 'arrands,' the deputy below informed us, would bring her home about dark, very much the worse for it. Think of that little child keeping guard on that dirty sack for six or eight hours at a stretch—think of her utter loneliness in that bare, desolate room, every childish impulse checked, left with orders 'not to move, or I'll kill yer,' and sitting there often till night and darkness came on, hungry, thirsty, and tired herself, but faithful to her trust to the last minute of the drunken mother's absence! 'Bless yer! I've known that young'un sit there eight 'our at a stretch. I've seen her there of a mornin' when I've come up to see if I could git the rint, and I've seen her there when I've come agin at night,' says the deputy. 'Lor, that ain't nothing—that ain't.'

Nothing! It is one of the saddest pictures I have seen for many a day. Poor little baby-sentinel!—left with a human life in its sole charge at four—neglected and overlooked: what will its girl-life be, when it grows old enough to think? I should like some of the little ones whose every wish is gratified, who have but to whimper to have, and who live surrounded by loving, smiling faces, and tendered by gentle hands, to see the little child in the bare garret sitting sentinel over the sleeping baby on the floor, and budging never an inch throughout the weary day from the place that her mother had bidden her stay in.

With our minds full of this pathetic picture of child-life in the 'Homes of the Poor,' we descend the crazy staircase, and get out into as much light as can find its way down these narrow alleys.

Outside we see a portly gentleman with a big gold chain across his capacious form, and an air of wealth and good living all over him. He is the owner of a whole block of property such as this, and he waxes rich on his rents. Strange as it may seem, these one-roomed outcasts are the best paying tenants in London. They pay so much for so little, and almost fight to get it. That they should be left to be thus exploited is a disgrace to the Legislature, which is never tired of protecting the oppressed of 'all races that on earth do dwell,' except those of that particular race who have the honour to be free-born Englishmen.

CHAPTER II.

As I glance over the notes I have jotted down during my journey through Outcasts' Land, the delicacy of the task I have undertaken comes home to me more forcibly than ever. The housing of the poor and the remedy for the existing state of things are matters I have so much at heart, that I fear lest I should not make ample use of the golden opportunities here afforded me of ventilating the subject. On the other hand, I hesitate to repel the reader, and, unfortunately, the best illustrations of the evils of overcrowding are repulsive to a degree.

Perhaps if I hint at a few of the very bad cases, it will be sufficient. Men and women of the world will be able to supply the details and draw the correct deductions; and it is, after all, only men and women of the world whose practical sympathy is likely to be enlisted by a revelation of the truth about the poor of great cities.

Come with me down this court, where at eleven o'clock in the morning a dead silence reigns. Every house is tenanted, but the blinds of the windows are down and the doors are shut. Blinds and doors! Yes, these luxuries are visible here. This is an aristocratic street, and the rents are paid regularly. There is no grinding poverty, no starvation here, and no large families to drag at the bread-winner. There is hardly any child-life here at all, for the men are thieves and highway cheats, and the women are of the class which has furnished the companions of such men from the earliest annals of roguedom.

The colony sleeps though the sun is high. The day with them is the idle time, and they reap their harvest in the hours of darkness. Later in the day, towards two o'clock, there will be signs of life; oaths and shouts will issue from the now silent rooms, and there will be fierce wrangles and fights over the division of ill-gotten gains. The spirit of murder hovers over this spot, for life is held of little account. There is a Bill Sikes and Nancy in scores of these tenements, and the brutal blow is ever the accompaniment of the brutal oath.

These people, remember, rub elbows with the honest labouring poor; their lives are no mystery to the boys and girls in the neighbourhood; the little girls often fetch Nancy's gin, and stand in a gaping crowd while Nancy and Bill exchange compliments on the doorstep, drawn from the well of Saxon, impure and utterly defiled. The little boys look up half with awe and half with admiration at the burly Sikes with his flash style, and delight in gossip concerning his talents as a 'crib-cracker,' and his adventures as a pickpocket: The poor—the honest poor—have been driven by the working of the Artizans' Dwellings Acts, and the clearance of rookery after rookery, to come and herd with thieves and wantons, to bring up their children in the last Alsatias, where lawlessness and violence still reign supreme.