Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

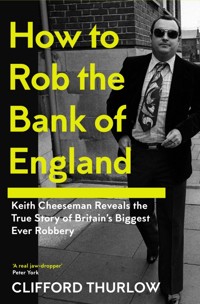

On a sunny May morning in 1990, a bank courier strode out of the Bank of England and, minutes later, was robbed at knifepoint of 301 bearer bonds valued at £292 million. It was the biggest theft in British history. The thing is... when Keith Cheeseman received a call from a disbarred lawyer connected to London's underworld and attended a meeting on the night of the robbery, he counted £427 million in bonds - £135 million more than the Bank of England had reported. As Keith set out to launder the bonds, Scotland Yard and the FBI were always one step ahead in tracking them down. Over the next eighteen months, two gangland figures were shot dead and more than eighty people were arrested. Keith was the only man ever jailed for the crime. Keith Cheeseman is the last of the old-time gangsters, a con man who detests violence, wears Savile Row suits and gold watches, and loves classic cars and good dining. He bought non-league Dunstable football club and signed Manchester United star George Best to play for the team. He knew the legendary Kray twins and killer Frankie Fraser once threatened to snuff him out him over a game of chess. So what happened to the missing £135 million? In this breathtaking adventure, featuring colourful characters from showbusiness alongside royalty, the IRA and even Pablo Escobar, Clifford Thurlow reveals Keith Cheeseman's incredible true story for the first time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 400

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in the UK in 2024 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

ISBN: 978-183773-135-0

eBook: 978-183773-137-4

Text copyright © 2024 Clifford Thurlow

The author has asserted his moral rights.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publisher will be pleased to make acknowledgement on future editions if notified.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by SJmagic DESIGN SERVICES, India

Printed and bound in the UK

CONTENTS

Prologue

1.Bird’s Eye View

2.The Mugging

3.Trustworthy with Criminal Intentions

4.Smurfing

5.Life Lessons

6.The Sweeney

7.Victimless Crime

8.The Great Unknown

9.The Spider’s Web

10.The Dutch Connection

11.Betrayal

12.Good Ole Boys

13.Defying Gravity

14.Murder in the Park

15.Above the Law

16.An Offer You Can’t Refuse

17.The Sting

18.The Crooked Sixpence

19.Everybody’s At It

20.The Big Fish

21.The Old Bailey

22.The Irish Curse

23.They’re Always Watching

24.The Darkest Hour

25.On Remand

26.Dymchurch

27.On the Run

28.Funny Bone

29.‘£290m Clue to Headless Corpse’

30.The Bengal Lancers

31.Fake News

32.Señor Dinero

33.The Untouchables

34.America

35.A Crime Against Money

36.Con Air

37.End Game

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

PROLOGUE

I am sitting beside the blue waters of the swimming pool with an open notebook and the hills of Anatolia rolling away in the distance. Keith Cheeseman is smoking a Montecristo. He flicks ash in a ceramic vase with patches of ancient glaze.

‘Roman,’ he says. ‘Even older than me.’

His wife Sarah appears with a tray holding a pot of coffee and two cups. She wears a pale green summer dress, a shade lighter than her eyes that sparkle and miss nothing.

‘Fancy a proper drink?’ Keith asks, and I glance at my watch.

‘It’s not even ten yet.’

‘When you do time, you don’t think about time.’

He looks back at Sarah with a slight shrug that she reads without asking. She strolls back into the villa and returns with a bottle of raki. She pours two shots and adds water. It turns the liquor milky. Keith takes a sip.

‘Now then, sunshine, where shall we start?’

I hit the record button on my phone.

‘Let’s start at the beginning.’

‘Once upon a time in a land bloody far away from here,’ he says and laughs.

He wets his lips and pauses for a moment. His expression grows serious and as he thinks back his eyes become as cloudy as the raki in his glass.

It all began on 2 May 1990. It was 9.30am when a courier left the Bank of England and two minutes later was robbed at knifepoint of a briefcase containing 292 bearer bonds worth £291.9 million.

It was the biggest heist in history. It made the Brink’s-Mat gold bullion haul of £26 million look like peanuts and the Great Train Robbery of £2.6 million seem like child’s play.

The robbery was so big it drew in an international network of criminals, arms dealers and terrorists, including the Mafia, the Provisional IRA and Colombian drugs king Pablo Escobar. It was the kind of money that can start wars and unseat governments. It changed the way banks made loans and hastened the pace of digital banking.

The theft by a young Jamaican wielding a knife appeared opportunistic. That was what the clandestine crime syndicate that planned the robbery wanted the police to believe. They needed to launder the bonds quickly and called in the well-known fraudster Keith Cheeseman to organise distribution.

During the next eighteen months, bonds hidden in ingenious ways were recovered in different places across the world. First, three men with links to the IRA were found with bonds in their luggage, in what the police described as a random search at Heathrow. Two telephone books with bonds between the pages posted to Escobar were found in Miami by US Customs. The FBI, posing as the Mafia, retrieved bonds in New York sent by London gangster Ray Ketteridge and carried by his solicitor Jeffrey Kershaw, who claimed he was a British police informer and went on the run.

Two gangland figures were murdered – both shot in the head.

Eighty people were arrested internationally, yet few were charged and those brought to court mysteriously walked free because prosecution ‘was not in the public interest’.

Shortly before Christmas 1991, British police announced that they had recovered all but two of the 292 stolen bonds.

Keith takes a long draw on his cigar and lets out a cloud of smoke.

‘This is where it gets interesting.’

I gulp down my raki.

The police spokesman on the six o’clock news reported that the sum stolen in bonds was £292 million, rounding up the loose change. The thing is, on the night of the robbery, Keith Cheeseman and a Swiss banker counted 450 bonds, worth £427 million.

What happened to the missing millions? Why the deceit, the cover up? Why did the IRA men and gangsters walk out of court with the charges dropped? And who was the informer who led the police and FBI to track down the bonds so quickly?

Only one man went to jail for the robbery and only one man knows the true story: Keith Cheeseman.

Now comfortably retired to his villa in Turkey, he has pieced together the complex puzzle of the biggest theft in British history and reveals its secrets for the first time.

Some of the dialogue has been fictionalised for the purposes of dramatisation, and some of the names have been changed to protect the guilty as well as the innocent. Not Keith Cheeseman. He has done his time.

He refills the glasses.

This is his story.

Clifford ThurlowTurkey, May 2023

1. BIRD’S EYE VIEW

It was a warm May morning in 1990, with the sun polishing the steel and glass walls of the NatWest building that rose over the cluster of City banks, insurance offices and, hidden from view, the Bank of England, with its Greek columns and the Union Jack fluttering above the roof as if to say all was well in the world.

And it was.

At least for Keith Cheeseman.

He moved away from the window. Keith hated the NatWest. In fact, his dislike of banks was such that he would have taken one down every day of the week if he’d had the chance. But there was something specifically irritating about the National Westminster, the way it blocked his view like a raised finger. He smiled.

I’ll have you one of these days.

He glanced around. An Englishman’s home is his castle. This was his, the penthouse at the Barbican, London, with fresh flowers in tall blue vases and Persian rugs neatly placed over shiny oakwood floors. Mrs Primrose, the cleaning lady, kept everything immaculate, the way he liked it. He had learned in the army there is a place for everything, and everyone has their place. He’d signed on at eighteen with the Royal Artillery in 1961 and did six years – an unlucky number intoned twice in his life by judges as they cracked their gavels down on the bench.

At 24 he entered civvy street with a vague plan to become richer than his rich brother. Keith didn’t find it hard making a living in business, but crime made him feel alive. It filled the empty spaces inside him, the sense of boredom, of repeating yourself. When you are on a job, you step out on the highwire. There’s no safety net. Every second is packed with life, that feeling that one slip and you’re dead. It is all-consuming. Aside from the money, he thought of robbing banks as a counterbalance to banks robbing everyone else, with their insatiable greed for profits that filter up to the shareholders and executives.

Was he going to charge into the NatWest with a sawn-off shotgun and a getaway driver outside with the motor running?

No.

Keith was a fraudster, a con man, the last of the old-time villains, men with pride in their craft, a certain honour among thieves who say fair cop when they’re collared, never carry a weapon and never grass. He thought of himself more as Robin Hood or Dick Turpin, looting banks, not to give to the poor exactly, but to spend lavishly and tip heavily. Trickle down, Mrs Thatcher called it. Defrauding banks is clean. If you dip into someone’s account, the bank is duty bound to repay the money. No one gets hurt – except the banks.

He strode down the hall in carpet slippers and put the kettle on. He took a grip on the roll of flesh over his waist then went up on his toes to stretch his shoulders. He was a big man, still fit from athletics and football – he could have gone pro, and had trials for Everton and Birmingham, but back in the day Stanley Matthews, the most famous player in the country, was only earning £23 a week. How could you live on that?

That’s the downside of the good life. You eat too much. You get addicted to the faint waft of the Caribbean every time you light a Montecristo. When you open a bottle of 1968 Château Lafite, you’re not going to leave half.

He poured hot water into a mug and settled it down on the coffee table in the living room. A shaft of light lit the volumes in his bookcase. He liked hardbacks, solid books with a leathery smell, made to last. He’d worked in a library once and discovered that reading takes a certain amount of skill. You have to come at a novel like you’ve met a stranger on an empty railway platform and you don’t know what’s going to come out of it. Life was like that. Every day was a new page.

On the table was a copy of War Plan UK, a book given to him by Martin Newman, a former fellow resident at Wormwood Scrubs. Duncan Campbell, the author, had a dire warning that Britain was unprepared for a nuclear strike. Not that Martin, with his Mick Jagger looks and starlet girlfriends, was worried about Reds under the bed. What interested him was the chapter describing the secret Ministry of Defence narrow-gauge railways, below the streets of London, being used to shuttle bags of cash between banks. Martin had got hold of a key and they had gone down for a recce. Robbing the train would need a six-man crew to pull it off. It had potential, but Keith didn’t like getting his hands dirty like a criminal.

He opened the book and read a few lines but couldn’t concentrate. Dust motes danced in the beam of light. His temple pulsed, a tell when you’re playing poker. He had a feeling, an intuition, that something was going to happen. Something massive, world changing. He took a sip of coffee.

That’s when the phone rang.

Keith glanced at his Rolex as he reached for the receiver. It had just gone 10am.

‘Hello.’

‘Morning, darling, you’re up early. What are you up to?’ Henry Nunn’s voice was posh, effete and confident.

‘You know, minding my own business,’ Keith answered.

‘That’ll be the day. Your nose is always in someone’s business.’

‘Yes, but only my nose.’

Nunn chuckled as Keith’s gaze fell on the Antonio Canova Venus on the shelf. The Capodimonte figurine – one of his favourites – was worth more than his new Jag in the car park below the building.

Henry was a disbarred lawyer, as bent as a paper clip and as much at home with the villains who ruled London as he was in the royal box at Ascot with the Duke of Edinburgh. Once upon a time, he sold the Duke a set of Irish flintlock pistols, not because he needed the money, but because it was ‘amusing’ to know there were firearms of ambiguous provenance in the palace. Henry had helped him furnish the apartment with dodgy objets d’art. As Keith liked to tell friends, he once had hanging over his bed a ‘Monet worth a lot of monet’.

He did a deal to put it back in the National Gallery where everyone could enjoy it and popped in for a nostalgic peek when Henry had tickets for a new exhibition. He liked Henry. He was a cross between Machiavelli and the Marquis de Sade – perverse, capricious, never dull.

‘Alright, Henry, what are you selling?’

‘Pas une chose. Not a thing, dear. I wondered if you’d like to come over this evening at about seven for une omelette française. Some of my chickens have come home to roost.’

‘Have they now?’

Henry’s tone changed. ‘Last time we met, I suggested you smooch some of your people …’

He left the sentence hanging.

‘That you did and that I did.’

‘Perhaps another little powwow is in order. We might be talking big numbers.’

‘There’s big and there’s big?’

‘Let’s say tons.’

‘Very nice, Henry. Two eggs for me …’

‘Sorry?’

‘In the omelette, dear boy.’

‘You mind your cholesterol.’ The voice went back to camp. ‘By the way, what happened to that gorgeous friend of yours?’

‘He’s not your type, mate.’

‘Don’t be so sure. See you at seven.’

2. THE MUGGING

Forty minutes before, at 9.30am, John Goddard buckled his briefcase and walked smartly down the steps from the Bank of England into Threadneedle Street. Goddard was a courier for Sheppards Moneybrokers, a man of 58, fit and sturdy in a grey suit and polished shoes.

He couldn’t help smiling. The sun does that. All the grey City men forever looking down at the rainswept pavements had straightened their backs and were marching along as if war had just been declared. He passed a girl in a blue-and-white dress.

‘Morning,’ she said.

‘Morning,’ he replied.

She was pretty.

In the briefcase he carried bearer bonds, to what value, he had no idea. It was not his position to know such things. His job was to make sure the package inside the briefcase safely reached its destination.

It was extraordinary – in fact, Keith Cheeseman found it hard to believe – that every working day, Monday to Friday, Goddard and scores of couriers like him walked up to £30 billion in bearer bonds back and forth across the Square Mile. No guards. No guns. Just men with good leather shoes, a steady pace, a look of quiet determination and a stout, if unpretentious, briefcase.

The bonds they transported were government treasury bills or certificates of credit supplied by commercial banks. Known collectively as bearer bonds, they carry huge numbers – £1 million was not unusual – and differ little from bank notes in that they ‘promise to pay the bearer’ the sum on the certificate. ‘On demand’.

It was through these bonds that banks lent and borrowed money short term and John Goddard felt that, in some small way, his role as a courier was the grease on the wheels that kept the money markets turning. He took a deep breath.

Was he getting older, or were the girls getting prettier?

He smiled to himself as he turned into Nicholas Lane, a narrow passage shaded by high Regency buildings.

Then …

… he really wasn’t sure what happened. How it happened. The sequence. The speed of it all.

A man stepped from the shadows and pressed a knife to his throat.

Time froze. He wasn’t afraid. There was no time to be afraid. It was like a dream. He saw himself as if from across the road looking at a stranger.

Then the man spoke, breaking the spell.

‘Don’t be a fucking hero. It ain’t your money.’

‘What …?’

The man wrested the briefcase from Goddard’s grip and sprinted off through the maze of City streets.

It was all over in five seconds.

The thief was Patrick Thomas, a petty crook of Jamaican descent, who kept running until he arrived breathless at Charlie’s Bar, where his friend Jimmy Tippett Junior was eating an egg and bacon sandwich. Tippett, then nineteen, was the son of the Jimmy Tippett, a prize fighter from South London who sometimes crossed the river for a few rounds at Repton Boxing Club. The former bath house in Bethnal Green, East London, was where the Kray Twins, Ronnie and Reggie, began their career of mayhem and murder.

Tippett was an enforcer, a dangerous man with imagination. One time, he was responsible for collecting a £100,000 gambling debt for the gangster Terry Coombs, at £10,000 a week. After three payments, the subject closed his wallet. Tippett went to the mortuary and came out with a bag containing a bloody arm that he hung on the debtor’s front door in Lewisham. The geezer, as he said, paid up with an extra £10,000 for taking liberties.

Writing in his autobiography, Born Gangster, young Tippett recalled his dad arriving home when he was a boy of six and tipping out carrier bags full of bank notes onto the bed. It was the life he wanted, the life he was born into, and it came as no surprise that Pat Thomas wanted to impress him. The Tippetts were crime royalty. Pat was a foot soldier without connections trying to make a name for himself – and easy to take advantage of.

Thomas had been told to deliver the briefcase without opening it. But criminals have big egos, and big mouths they can’t help putting their feet into. He couldn’t resist showing off the haul and had to wait until Tippett had finished his sandwich.

‘Alright, you got me,’ Tippett said, wiping his lips and lighting a king-sized. ‘What’s in the case?’

‘Let’s go in the toilets and have a look.’

‘Whoa, steady on. You’re not going all Boy George on me …’

‘Once you go black ...’

They laughed and puffed on their Rothmans. They squeezed into a toilet cubicle and Thomas unbuckled the briefcase. If he was expecting to find diamond rings and strings of pearls, he would have been disappointed. Inside the case were a dozen folders in different colours. Each folder contained certificates that Tippett recalled ‘looked like the kind of thing you get at school for swimming ten lengths’ – except these certificates were embossed with the names of various high street banks, the Alliance and Leicester, Nationwide, Abbey National and the National Westminster. Printed in fancy lettering were very large sums – up to £1 million.

‘Fuck me.’

‘Let’s have a couple,’ Tippett said. ‘Nobody’ll miss ’em.’

‘You having a laugh? They’re numbered, look. I just wanted to see what it was for myself.’

‘You didn’t know? Fuck me. Who set this up, then?’

‘Some poofter. I got a call, didn’t I …’

‘You got a call? Who are you, James fucking Bond?’ Tippet flicked through the certificates in one of the files. ‘There’s millions here.’ He looked up at Thomas. ‘This is too big for you, mate. This is 25 years.’

Thomas’s face broke into the sort of smile men have when their horse comes in at 20–1.

‘It’s the big time, innit.’

Thomas resealed the briefcase and the last Jimmy Tippett saw of him that day was ‘swaggering out of Charlie’s Bar’.

John Goddard was rigid with shock but unharmed. He shook himself, took a breath, and ran back to the Bank of England.

Banks give the impression that their venerable institutions, housed in buildings that look like churches and temples, are slow and ponderous, that bankers are priests there to serve the public good. Like much in the banking world, this is false. Banks are always ahead of the curve when it comes to technology and move when the need arises like hares, not tortoises.

During the twenty minutes Pat Thomas spent with Jimmy Tippett in Charlie’s Bar, bankers with nice accents were screaming down telephones and the serial numbers of the stolen bonds were gliding over computer terminals in banks across the globe.

Executives from Sheppards sprinted fast as express trains to Lloyds of London, the world’s most famous insurance company, with its boast: ‘Proud to take on any type of risk.’ They sat down with the insurance brokers and senior police officers, good chaps in tailor-made suits, acquainted with each other through public school and gentlemen’s clubs.

The moneybrokers revealed that the briefcase carried by John Goddard had contained 292 bearer bonds worth in total just under £292 million.

‘Say that again,’ said one of the policemen.

‘£292 million.’

‘In a briefcase?’

‘It would have needed a Transit van to carry it in cash.’

They sighed and shook their heads. A woman dressed in black with a white apron brought in tea in porcelain cups and plates of biscuits, the English way, and they got down to business.

From Goddard’s description of a knife-carrying young black man, police profilers reasoned that the robbery had been random, a one-in-a-million happenstance. Detective Chief Superintendent (DCS) Tom Dickinson, in charge of the investigation, believed the mugger would find what to him looked like worthless certificates and throw them away.

‘I expect we’ll have the case solved in a matter of days,’ he boasted.

Sheppards had minimal insurance against the bonds being stolen – it had never happened before – but needed to up the premium in case they were never recovered. Lloyds set the increase at £750,000, which the moneybrokers agreed to pay.

DCS Dickinson glanced across the table at the broker from Sheppards as if it were his fault. ‘This was a crime waiting to happen,’ he added, and the good chaps nodded their heads and stirred their tea.

What the men gathered in that room did not know was that the police hypothesis, that the mugging was opportunistic, was exactly what those behind the robbery had anticipated and planned for.

What they had not planned for was the lost twenty minutes Thomas had spent at Charlie’s Bar with Jimmy Tippett, giving the Bank of England time to circulate the serial numbers of the stolen bonds.

The delay cost the criminals millions of pounds and would cost Patrick Thomas his life.

3. TRUSTWORTHY WITH CRIMINAL INTENTIONS

Keith Cheeseman had been anticipating a bonds heist since January, when a courier working for Rowe & Pitman had forgotten to secure the straps on his briefcase and dropped £4 million in certificates of deposit on his way to the Bank of England.

A young surveyor found the bonds outside the Stock Exchange on Throgmorton Street and marched straight into the lobby to hand them in. He was rewarded with a magnum of Laurent-Perrier champagne and enjoyed fifteen minutes of fame being photographed by the newspapers.

The coverage did not go unnoticed.

Two weeks before the robbery, Cheeseman had met Martin Newman for coffee at the Café Royal in Regent Street. That’s when Martin had given him the copy of War Plan UK that he’d bought – or lifted – that morning at Foyles, Keith’s favourite bookshop, on Charing Cross Road. As they were leaving, they bumped into Henry Nunn in his tight-fitting pinstripes with a rosebud in the buttonhole. Keith introduced them.

‘Martin, my old mate Henry. Watch yourself, he’s the king of the shirt-lifters.’

They shook hands. Henry fluttered his eyelashes as he sized up Martin. With his long hair and black leather jacket he was not within the dress code for the Café Royal, but the maître d’ turned a blind eye for those who brought style. Under his jacket, Martin wore a scoop-necked red vest revealing a lush carpet of chest hair.

‘Honestly, I prefer those who have already abandoned their shirts,’ Henry remarked. His tone changed as he turned to Cheeseman, with lines deepening on his brow. ‘Are you still in touch with your friend in Indonesia?’

‘Lovely chap. Wife’s got a new poodle.’

‘Jolly good.’ Henry turned back to Martin with a smile. ‘So nice to have met you.’

He climbed the stairs and waved as someone came down to meet him.

The robbery was all over the BBC at 6pm and it occurred to Keith that news is always a mixture of truths, half-truths and bollocks. The DCS in his shiny suit kept a straight face as he told the British public that a thief working alone had nicked bearer bonds worth £292 million and ‘wouldn’t be able to spend a penny’ because the serial numbers had been circulated ‘to every bank in the world’.

Detective Chief Superintendent Dickinson knew that the statement was untrue. Once minted, bearer bonds have the same versatility as uncut diamonds, whether the serial numbers are known or not. Using bearer bonds to hide and move assets may not be cheap, but it is easy. There are law firms and chartered accountants in the City that don’t display brass plaques, and behind their closed doors all your financial needs will be met with no questions asked. As there is no record of who the seller is or who is buying the bonds, you can move money in high denominations and store it in fiscal paradises, where the sun always shines on fishermen casting their nets in picturesque bays and omertà is a way of life.

Terrorists and criminals trade stolen bonds as collateral in arms deals, drug deals, terror plots and property speculation. Bonds washed through private banks in tax havens finance wars and overthrow governments. When Colonel Oliver North diverted cash from weapons sales to Iran in 1985 to fund the American-backed Contras plotting to oust the socialist government in Nicaragua, they used bearer bonds as security.

Keith remembered watching the movie Die Hard at the Odeon Leicester Square. Alan Rickman, playing the lead bad guy, swipes bonds worth $640 million in a couple of duffel bags and tells his gang that by the time the authorities know they’ve gone ‘they’ll be sitting on a beach earning 20 per cent’. Keith felt as if he were standing in Rickman’s shoes all the way to the final fist fight when Bruce Willis as a New York detective foils the plot.

And now in other news …

… while police search for the bond robber, poll tax rioters continue to occupy Trafalgar Square …

Keith turned off the TV and poured himself a gin with a lot of tonic.

He had made that call after lunch. His conversation with Abyasa Tjay – TJ to his mates, lasted 90 seconds.

‘TJ ...’

‘The answer is yes,’ he said the moment he heard Keith’s voice.

‘You can’t have heard already?’

‘You forget, my friend, we are always ahead of you in London – by six hours.’

‘Still …’

TJ was in.

Big time.

The bubbles from the tonic went up Keith’s nose and made him laugh. For some reason, what came into his mind was the night at the Waldorf Astoria in New York in June the previous year when he first met TJ. Vice President George Bush happened to be there at the same time, visiting the long-time Indonesian President Suharto who, like Picasso, was generally known by a solitary name. The Astoria was the watering hole for those in the pink, in the know and on the make.

Keith had forgotten his wallet and was in the lift ready to go up to his suite when a secret service man in a black suit caught the doors before they closed. George Bush entered with an escort of aides.

‘I do apologise for holding you up,’ he said.

‘That’s alright. Got all the time in the world,’ Keith replied.

‘Oh, you’re English.’

‘Keith Cheeseman.’

‘I’m George.’

‘I know, sir, the vice president.’

‘For my sins. Lovely country, England. Always a pleasure to visit.’

‘Except for the bloody rain.’

George laughed.

They stepped out on the top floor. Keith collected his wallet and went back to Peacock Alley, the lobby bar, to join Rocky Graziano; the one-time middleweight boxing champion of the world was looking for partners to buy a vineyard in Napa Valley. They were still there when George Bush passed through with his men in black.

‘Hi there, Champ. Hi, Keith,’ he called.

After this fleeting acknowledgement from the vice president, Keith always got the best table in the restaurant and was treated as a VIP by all the staff in the hotel.

Later that evening, he was having a drink with Ben Blessing, an American based in Holland. Blessing was an icon, a mythical figure, the man little boys who dreamed of scamming banks wanted to be when they grew up. His reputation had earned him the sobriquet Mr Big.

A group of Indonesian women dripping in gold and wearing sparkling dresses passed through the lobby like a flock of chattering parrots. TJ was following them but peeled off when he saw Blessing and headed towards the two men. Ben introduced them. TJ had a firm grip when they shook hands and looked Keith in the eye as if he were taking an X-ray. He was related by marriage to the old butcher Suharto, but probably had bigger ambitions.

‘Are you here on business, Mr Cheeseman?’

‘I am.’

‘And what is your business, if you don’t mind my asking?’

‘I rob banks.’

‘With a fountain pen,’ Blessing added.

TJ didn’t laugh. He glanced at Blessing, then lowered his voice. ‘It is the only way to live,’ he said. ‘Do excuse me, I must take care of the concubines …’

Keith met TJ again later that year, in Florida with Mark Lee Osborne, a disqualified bond trader from Texas. Keith had some JC Penney bonds with mixed values of $10,000 and $20,000 he wanted to cash in. TJ glanced at the bonds and shook his head. The sums were too small for him to deal with.

‘May I tell you a story I was told by my father?’ he said and sipped his drink. ‘There are two bulls in a field above a meadow with a herd of cows. The young bull says: let’s rush down there, cross the fence and fuck a cow. The old bull is silent for a moment, then he says to his young friend: no, let’s go down there slowly, cross the fence and fuck them all.’

‘Hey, that’s funny,’ Mark Osborne said.

‘It is not a joke, Mark.’

They went out to eat at an Indonesian restaurant. TJ introduced Keith to nasi goreng, the national dish, and he introduced TJ to the Silver Oak Cabernet Sauvignon from California at $60 a bottle. They bonded over their love of bonds and Keith returned home confident that he had a good contact when the right deal came along. He flew back to the UK on Concorde, always a good place to meet people, and searches were cursory, if they happened at all.

He straightened his dark-blue-and-plum-red-striped tie and slipped on his suit jacket. The lift took him down to the car park in the basement where his green 2.4-litre Jag was as shiny as an emerald in the half-light. Rodney Miller, the doorman, was waiting to go up.

‘Evening, governor,’ he said.

‘You been polishing my car again?’

‘Lovely motor. Going somewhere nice?’

‘Who’s asking? You working for MI6?’

‘That’s my secret, Mr Cheeseman.’ He lit a rollup. ‘You hear about that robbery? Millions some bloke got away with.’

‘Hope he enjoys spending it, that’s what I say.’ They laughed and Keith tucked a tenner in Miller’s top pocket.

‘I don’t want that,’ he said.

‘Easy come. Easy go. One of my chickens came home to roost.’

‘Nice one. Don’t get that bloody motor dirty.’

Keith climbed in the car. The big engine roared like a 747 and it wasn’t easy sticking to the speed limit driving to Mayfair. The roads were empty. Everyone was either rioting over Maggie’s poll tax or staying at home to avoid it. He parked in a meter slot and locked up. It was warm still. The sun had turned the windows orange along the length of Seymour Place with its red-brick mansion blocks and houses with marble steps and columns.

He crossed the road to Henry’s place, an Aladdin’s cave crammed with high-ticket antiques and paintings by old masters. There was a Goya in the kitchen, a row of Dalí prints in the hall and the front door wasn’t locked. He closed it with a bang so Henry knew he’d arrived. It was 7.10pm. A champagne cork popped as he entered the living room and Henry filled six glasses.

‘A toast,’ he said. ‘To us.’ They clinked their crystal flutes.

They were, Keith thought, an odd bunch. Henry with his fleshy pink face, grey eyes sharp as flint and the permanent look of vague disdain that comes to those who have seen and done it all – at least twice. At his side stood Roger, his ‘assistant’, whom Keith had met before. Feminine, amenable, forgettable, he sipped from his glass and stole into the shadows.

There was a big Irishman named Houlihan in a donkey jacket who looked as if he had just strolled in from a building site. He pulled a sour face drinking the champagne, but apart from that his expression never changed. He watched and listened, the eyes and ears of someone higher up the food chain.

Henry introduced Keith to John Bowman. He was English, tall with pale-blue eyes and waves of silver hair, a banker based in Switzerland with a young Swiss wife and two sons at Charterhouse. He wore a signet ring with a crest on the pinkie finger of his left hand, and Keith could tell from his Armani suit and bench-made Oxfords that he had the expensive tastes of someone always two quid short of a fiver.

‘So nice to meet you finally,’ he said.

‘Finally?’

‘Henry has filled me in.’

‘He’s going to get himself filled in one of these days.’

Ray Ketteridge had crossed the room and lifted a briefcase on to a round mahogany table.

‘Here we are, Keif, come and take a butcher’s.’

He squared up in a boxer’s pose as Keith approached. Keith raised his fists in response.

‘What do you reckon?’ Ray said. ‘Think you can take me?’

‘As long as you’ve got one arm tied behind your back.’

‘You still wouldn’t have a chance.’

‘Unless I kick you in the bollocks.’

‘That ain’t Queensberry, is it?’

Ray straightened his shoulders and gave Keith what he thought of as a friendly slap on one cheek, which Keith didn’t like but let it go.

‘How’re you keeping, son?’ Ray asked.

‘You know. Can’t complain.’

‘This time next week, you won’t have anything to complain about.’

‘You don’t know my wife.’

He laughed. ‘You’re a bloody comedian, Keif, you know that.’

Ray Ketteridge was a hard man inside a Savile Row suit who must have seen Michael Caine in Neil Jordan’s movie Mona Lisa and styled himself on the actor. To be fair, he did look like Caine, broad, handsome, his quiff of fair hair bronzed by the sun on the Costa del Crime, as the tabloids called the Spanish coast.

This was the second time Keith and Ray had met. The first had taken place after a last-minute invite from Henry Nunn to meet at Tramp, the nightclub in Jermyn Street. When Keith arrived, Nunn and Ketteridge were at a corner table with a plump chap with the dishevelled look of those who wear shirts with frayed collars to show they went to the best schools. He stood immediately, with a broad smile, and spoke with a lisp.

‘So you are K-K-Keith Cheeseman,’ he said, before they were introduced.

‘And you are?’

‘N-n-nobody. N-n-nobody who matters.’ He waved over his shoulder as he left. ‘Have a p-pleasant evening.’

Ketteridge snapped his fingers and the waitress came running over.

‘Who’s that then?’ Keith asked.

‘We were at Gordonstoun,’ Nunn answered. ‘Best shot in England, so he tells anyone who will listen. So glad you could join us.’

The previous year, Ketteridge had been implicated in a £32-million bank fraud in France. After spending nine months on remand, Nunn had pulled strings to get him out of jail. It’s a cliché to say it’s who you know, but clichés are usually spot on. Nunn managed to get the charges dropped and Cheeseman had a funny feeling that it involved the man with the frayed shirt and stammer. ‘No names, no pack drill, as we used to say in the army.’

They drank whisky and ate nuts from bowls the waitress kept filling. There was dance music. Nobody danced. It was too early. When Princess Margaret appeared in a cloud of smoke and hangers-on it was never before midnight. Keith had been at the club one night when the owner, Johnny Gold, chucked out a couple of Georges for being too drunk – his mate George Best and singer George Michael. On another occasion, Keith watched Prince Andrew on his first date with the actress Koo Stark and, later, Andy was often on the dance floor clutching Sarah Ferguson like a drowning man to a lifeline. That was before they married in 1986.

Henry Nunn crossed one well-pressed trouser leg over the other and gazed about him with the relaxed smile of someone who has just found the answer to a difficult clue in a crossword. He was a spider at the centre of a web of aristocrats and gangsters and had come to see that these two groups, who at first glance appear to be opposites, had in common a love of the good life, ambiguous morals and an unconscionable fear of boredom. An introduction from Henry Nunn said you were trustworthy with criminal intentions.

Villains are like washerwomen; they love to gossip. Who’s in jail. Who just got out. Who nicked what and who fenced it. How their sister once dated Reggie Kray and they went three rounds with Frank Bruno. Getting involved in, and escaping scot-free, from the French job gave Ray Ketteridge his bona fides. He was a player in the same game as Keith Cheeseman.

Keith had become renowned in criminal circles when his story went public at the Old Bailey and his name was splashed across the tabloids. In partnership with Lord Angus Montagu, he had bought non-league Dunstable Town Football Club and persuaded soccer legend George Best to come out of retirement to play for the team. Keith opened dozens of accounts in fictitious names and made £300,000 taking out false loans at the Beneficial Bank. He was arrested with Lord Montagu when the fraud was discovered. In the High Court Keith was convicted and served almost four years of a six-year sentence. Angus Montagu had pleaded not guilty and was acquitted.

‘One law for them, one law for us,’ Ray remarked.

‘As it should be,’ Nunn added.

They both looked at Nunn and looked back at each other, aware that what was meant to sound funny wasn’t funny at all.

4. SMURFING

The ormolu clock on the mantel chimed the half hour as Keith watched Ketteridge unbuckle the briefcase. From it he removed twelve different coloured files. He made two stacks, six files in each.

‘Keif, Jonny. Let’s see what we’ve got.’

Keith unpacked the bonds and kept them in six piles around one side of the table. He went through each pile, counting in his head. Bowman did the same. They stood back, the table decorated like a handless clock.

‘I make it £210 million,’ Keith said.

Bowman looked back at him as if he’d just been stung by a wasp. ‘Mine’s £217 million.’

‘What’s that make?’ Ketteridge asked.

Bowman stroked his wave of hair. ‘It comes to £427 million.’

‘Now that is a surprise,’ Ketteridge said, and Keith registered no surprise in his voice at all.

Keith and Bowman counted the opposite piles and reached the same total. The six men stood there in silence. On the polished mahogany table in Henry Nunn’s living room, they were not looking at 292 bonds worth £292 million, as DCS Dickinson had reported on the six o’clock news. What they had was a little less than a ream of A4 paper, weighing about five pounds, consisting of 427 bonds worth £427 million.

‘What lucky boys we are,’ Henry said, breaking the silence. His expression in the dimming light showed no change.

Keith lit a cigar and glanced through the smoke from Ketteridge to Nunn and back again. Ray had thrust his hands in his trouser pockets and looked like a huge crow about to take flight. £427 million – with a buying power of more than £10 billion in 2023 – was head turning, mind blowing, unrealistic. Had it been 26 million, like the Brink’s-Mat robbery, they would have shifted the bonds in a fortnight and all had a nice pay day. £427 million was an ocean, and he could see them all drowning in it if they weren’t careful.

‘What do you reckon, Jonny?’ Ray asked, and Keith noticed Bowman’s hands were shaking.

‘We can restructure a portion,’ he replied.

‘Smurfing,’ Keith added.

Ray looked back at Bowman. ‘You explain it to me as if I’m a monkey.’

‘Restructuring is breaking up large transactions into smaller ones so as to avoid detection. As a debt security, bearer bonds are not registered. It’s a loophole built into the system for investors who want to remain anonymous.’

‘The stinking rich,’ Ray said.

‘That means whoever holds the paper is presumed to be the owner.’

Ray shook his head. ‘What’s this about smurfing then?’

‘Just slang,’ Keith replied. ‘You know those little blue cartoon characters called Smurfs? They divide up tasks the same way funds have to be divided before they’re invested.’

Bowman continued. ‘The international banking system is like a river. We open shell companies using individual bonds as capital and slip them into the flow. As we shift the capital through different companies and different banks, the original deposit is washed away and the cash is laundered.’

‘How long’s that going to take?’

Keith blew out smoke. ‘For this lot? About 100 years.’

‘You have other ideas, Keith?’ asked Nunn, knowing that he did.

‘I do, as it happens. I spoke to my contact today in Indonesia.’ Ray had been pacing about. Now he stopped to listen. ‘He said he’ll take £200 million …’

There was an inward rush of air as they all took a breath. Even Houlihan’s dead eyes came to life.

‘At 25 per cent.’

‘What’s that, £50 million?’ Ray said. ‘You must be fucking joking.’

‘No, Ray, I am not joking. It’s a good rate.’

‘Fucking 25 cent. Who is this geezer, anyway? I don’t even know where bloody Indonesia is.’

‘Far East. You know, Philippines, Korea. Next to Australia. Our bloke’s related to President Suharto. He has a position in the Treasury.’

‘I dunno, Keif. I don’t trust foreigners. How do we know he’ll pay up?’

‘That’s not a problem. The money’ll go in escrow.’

He glanced at Bowman. ‘What’s that, then, Jonny?’

‘We would engage an escrow agent who works as a neutral third party. They hold the bonds offshore for us and the cash offshore for the buyer. They make the exchange when the two parties come together.’

‘And charge for it?’

‘A relatively small sum.’

‘I still don’t trust bloody foreigners. Or banks.’

It struck Keith that Ray Ketteridge saw a £1-million bearer bond as being worth £1 million, its face value, which it is if it’s legit. Twenty-five per cent on £200 million for hot bonds was the best deal they were going to get. Ray didn’t seem to know that.

‘What do you think, Henry?’ Keith asked.

‘Not my decision, dear boy.’

‘It might not be your decision, but what do you think?’ Keith persisted. ‘We’re not talking about five grand, are we? We’re talking about 50 mil.’

Henry glanced at Ray. Ray was out of his depth and Keith couldn’t work out why Henry wasn’t pulling him out of the water. Why had the police reported that 292 bonds had been stolen when there were 427 on the table? Who had set up the robbery and who stood to gain from the 135 unrecorded bonds worth £135 million at face value? What did Ray Ketteridge and Henry Nunn know that the police didn’t?

There were a lot of questions Keith Cheeseman wanted to ask, but this was not the appropriate time. It was actually the time to bow out gracefully. But, then, when you’re standing next to almost half-a-billion quid in bonds freshly nicked from the Bank of England, your toes tingle and there’s an adrenaline rush that hits the brain like a Class A drug. Fuck it, he thought, I’m in for the ride.

‘I don’t want to press you, Ray, I’ll just say it once more. Twenty-five per cent on 200 mil is a very good rate. My man will fly out to Panama or wherever and have the money sitting in the bank. We’ll shift our bonds there and the escrow dealer will put us together. The going rate for the dealer is 2 per cent. That’s a million on 50 mil. We come home with £49 million in offshore deposits and a suntan.’

‘You may be right, Keif. It’s a good rate if we can’t get better,’ he replied and shoved his hands back in his pockets. ‘The fing is, how’s this foreign geezer reckon he’s going to shift that kind of number?’

‘I don’t know, Ray. I don’t know how the engine in my Jag works. I just turn the key and drive it. Banks in the Far East run by their own rules. He’ll probably slip it into the Treasury on some bogus oil deal and clean it through shell companies and trusts – smurfing big time.’

They were silent again. The room had grown dark. Roger switched on the lights. Ray paced, smoking, and stopped to stub his fag out.

‘This is early days,’ Henry Nunn said. ‘We don’t have to do anything definitive tonight.’

Ray glanced at Keith. ‘See, a word from the wise,’ he said. ‘Keep the doors open. Let’s think about this.’ He counted out five bonds and gave them to Bowman. ‘See what you can do with these.’

He counted out another five and gave them to Keith. ‘Talking about 25 per cent, Keif, that’s your piece. See what you can get.’

Houlihan watched as Keith folded the five bonds neatly in three and slid them into his inside jacket pocket.

5. LIFE LESSONS

For Keith, banks were poison and bankers shady shysters who care about nothing but personal bonuses and shareholder profits. His disdain began in 1972 when his building company – W.W. Parrish West Midlands – had £7-million worth of work on the books and Barclays and the local branch of the Bank of Ireland both cancelled his overdraft facility for no apparent reason. He borrowed money from mates and had to pay it back at high interest.

When banks crash, the government dips into the Treasury to bail them out. When businesses crash it’s like a glass dropping on a stone floor, they smash into a million pieces. The lesson Keith learned was that if you are in the building game, the way to get ahead is to get local government contracts with their guaranteed finance. To get through that barred and bolted door, it’s not what you know …