Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: V&Q Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Deutsch

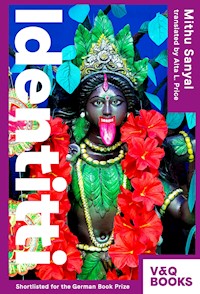

THE SELLOUT meets INTERIOR CHINATOWN in this satirical debut about race, sexuality and truth. German-Polish-Indian student Nivedita's world is upended when she discovers that her beloved professor who passed for Indian was born white. Nivedita (a.k.a. Identitti), a doctoral student who blogs about race with the help of Hindu goddess Kali, is in awe of Saraswati, her outrageous superstar post-colonial and race studies tutor. But Nivedita's life and sense of self begin to unravel when it emerges that Saraswati is actually white. Hours before she learns the truth Nivedita praises her tutor in a radio interview, jeopardising her own reputation and igniting an angry backlash among her peers and online community. Dumped by her boyfriend and disowned by her friends in the uproar, Nivedita is drawn to her supervisor in search of answers not only about Saraswati's identity, but also around her own. In her thought-provoking, complex and genre-bending debut, Mithu Sanyal collages commentary from real-life intellectuals, blogs, articles, race theory and academic warfare, combining campus novel and coming-of-age drama. A darkly comedic tour de force astutely translated by Alta L. Price, Identitti showcases the outsized power of social media in the current debates around identity politics and the power of claiming your own voice.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 606

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Mithu Sanyal is a cultural scientist, journalist, critic and author of two academic books: Vulva, which was translated into five languages, and Rape, which was translated into three languages. This is her first novel.

Alta L. Price runs a publishing consultancy specialising in literature and non-fiction texts on art, architecture, design, and culture. A recipient of the Gutekunst Prize, she translates from Italian and German into English.

IDENTITTI

A novel

Mithu Sanyal

Translated from the Germanby Alta L. Price

V&Q Books, Berlin 2022

An imprint of Verlag Voland & Quist GmbH

First published in the German language as Identitti by Mithu Sanyal

© 2021 Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co KG, Munich

This English translation was first published in North America by Astra Publishing House of 19 West 21st Street, #1201, New York, New York 10010.

English translation © Alta L. Price

Copy editing: Kate Ellis

Author photo © Carolin Windel / Stern

Cover photo: Getti Images

Cover design: Pingundpong*Gestaltungsbüro

Typesetting: Fred Uhde

Printing and binding: PBtisk, Příbram, Czech Republic

ISBN: 978-3-86391-339-7

eISBN: 978-3-86391-357-1

www.vq-books.eu

FOR DURGA – AND MATTI

CONTENTS

PART 1 : FAKE BLUES

The Devil and Me

Strange Fruit

Coconut Woman

Down on Me

If I Had a Hammer

Bang Bang Bang Bang

PART 2: POP-POSTCOLONIALISM

Woman, Native, Other

Peau Noire, Masques Blancs

Orientalism

The Location of Culture

Can the Subaltern Speak?

Decolonising the Mind

PART 3 : CODA

The Academic Formerly Known as Saraswati

AFTERWORD: REAL AND IMAGINED VOICES

TRANSLATOR’S POSTSCRIPT

SARASWATI’S LIT LIST

PART1:

FAKE BLUES

THE DEVIL AND ME

IDENTITTI

A BLOG BY MIXED-RACE WONDER WOMAN

About me:

The last time I spoke to the devil he was naked, visibly aroused, and female. So much for social certainties, right? If you can’t even count on the devil being male, you might as well shed all forms of identity like you would a worn-out T-shirt – which is precisely what I’d like to do, if only I had one to slip into, let alone out of. That’s exactly what all this was about, just like every other encounter with my devil, who’s actually a devi – an Indian goddess with too many arms, wearing a necklace made of her enemies’ severed heads. Yes, I’m talking about Kali. ‘Demons, the lot of ’em,’ she said, in the same dismissive tone my cousin Priti would use to say, ‘Men, the lot of ’em,’ and then she shook her necklace until her slain foes’ teeth chattered. Sure enough, Kali’s demon heads all looked suspiciously like men’s heads.

But she’d already moved on to other things. ‘Let’s have a squirting match, whoever shoots farthest wins.’

I nodded at her hairy vulva, taken aback. ‘How do you plan to …?’

‘Hah! Jizzing isn’t just for cis men,’ Kali shouted, beaming so triumphantly that for a moment I didn’t even notice she’d just said cis. ‘And why would it be? We had three genders eons before your god was even born.’

‘But you’re my goddess,’ I reminded her.

‘I thought I was your devil …’

‘What’s the difference?’

Race & sex. Whenever Kali and I talked, it was always about race & sex. Meaning – for lack of a more accurate term, or any term whatsoever that won’t send us down a rabbit hole – it was about my relationship to Germany and India, my two neither-mother-nor-fatherlands (remember, I’m Mixed-Race Wonder Whatever), and … sex. This blog is mostly transcripts of our conversations. If you read on, I’ll eventually tell you why I’m always talking to a goddess. My name is Nivedita Anand. You can call me IDENTITTI.

COCONUT WOMAN

1

Nivedita was twenty-three when she first met Saraswati, who was almost twice as old at the time.

She had highlighted Saraswati’s seminar in the expanded course catalogue, ringing it in ink, multiple times. But, whereas most professors understood ‘expanded’ as a cue to add further comment on the course content, Saraswati had instead just riffed ‘Kali studies – come and find out if you can study a goddess,’ with an image of Kali underneath. Nivedita’s Kali. Nude, Black, sticking out her tongue, wearing a skirt of dismembered arms. The very Kali with whom Nivedita was already and always having endless conversations, albeit in her head, both when the world made no sense and when it made too much sense. The very Kali she’d followed each night of her entire life, who had led her off to sleep or had led her to stay awake, focused on the mere memory of sleep, and had danced through her earliest dreams.

Nivedita was still too young to read on her own, so it must’ve been her mother who read her Little Red Riding Hood. In any case, there she was, smack in the middle of a sentence, standing in a fairy-tale forest that looked suspiciously like a rain forest (maybe it was actually The Jungle Book her mother had read to her?) and from the dense foliage she spotted a dark figure waving to her with two arms while using all her other arms to part the branches. Nivedita immediately recognised Kali as the goddess whose image hung all over her parents’ home – she even popped up in the family car, as a little figurine stuck to the dashboard, head bobbing, arms waving. So she posed the burning question she’d been asking herself ever since the very first time her little-girl finger had poked at that Kali figurine in order to bring it to life: ‘Why do you have so many arms, Kali?’ Except in the dream, she formulated it as an exclamation, just like in the fairy tale: ‘Kali, how many arms you have!’

Kali’s long red tongue unfurled from her wide smile. ‘All the better to hug you with, my child!’

Seeing the course title Kali Studies was like getting a message from that childhood, a world where identities were the stuff of fairy tales in which anything was possible and, just to make sure it wasn’t overly harmonious, there was always a bunch of mischievous djinns standing by, ready to turn everything upside down, muddle every norm, and remix every notion of morality. Nivedita had just moved from Essen to Düsseldorf, was settling into a new apartment, and beginning her first year as a masters student in the Intercultural Studies and Postcolonial Theory programme. She welcomed this familiar fragment from the past with all the ardour of her own astonishment.

‘Kali Studies?’ Priti echoed over Skype those three long years ago, back when they spoke nearly every night, since both had just relocated. Priti had just landed in London, in the Department of War Studies at King’s College (in reality she hadn’t got into the War Studies programme, and had instead enrolled in German Studies, but by the time Nivedita found out it was already too late). ‘Everyone here is destined for the civil service,’ Priti continued, undaunted, ‘or government. While you all … I mean, Kali Studies? Where will that take you?’

A knock at the door saved her from having to answer.

‘Yeah?’

‘Well, what do you say – should we check it out?’ asked Charlotte, her second flatmate (who of course went by Lotte) as she strolled right in, cheeks aglow. Lotte was one of those giraffe-type women, super tall and lanky, long arms, long torso, and hardly any discernible waistline, so her overall look was less erotic than elegant. And of course Priti, who ranked everyone according to sexiness, didn’t refrain from visibly expressing her verdict. Nivedita turned her laptop aside as Priti gestured – slicing her neck one, two, three times with her index finger – trying to keep her cousin outside her flatmate’s line of vision. All the while, Lotte rambled on with an endless stream of info, room numbers, times, days of the week, so it took Nivedita a while to catch on to what seminar Lotte was even talking about. But as soon as she said the magic name, it unexpectedly clicked.

Nivedita had thought she was the only one interested in Kali. And her intimate knowledge of the Indian goddess now spilled over onto Saraswati, whom she hadn’t even met yet, so that in her mind the two of them fused into a single figure that promptly promised to take Nivedita into her many arms. It felt as if Lotte had caught her in the middle of some particularly kinky foreplay.

‘Not Kinky Studies – Kali Studies,’ clarified Lotte, who of course already knew everything there was to know, at least about the professor. ‘She’s a total cult figure,’ she said, trying to punctuate the pronouncement with a dramatic pause but then failing, as the words just kept gushing from her mouth. ‘Everybody’s talking about her, Nivedita! Ev-er-y-bo-dy! Didn’t you see her on that talk show? None other than Sandra Maischberger interviewed her – or was it Markus Lanz? Maybe both. I’m just afraid we might not get a spot.’

So it was that two days later Nivedita and Lotte biked to campus together and squeezed into a standing-room-only lecture theatre to await the arrival of the legendary Saraswati, who was clearly on her own schedule.

Fifteen minutes past the academically accepted fifteen-minute cushion she finally stormed in, dupatta streaming, flung her leather briefcase onto the lectern, and paused in front of the blackboard, her back to everyone, as if she had to gather herself for a second before diving into the seminar, unveiling the provocation. Her hair cascaded long and black and heavy down her nape, causing the hair on Nivedita’s own nape to shiver with a sensory memory of bristles tickling her skin when Priti used to brush it – an all-enveloping, synaesthetic, whole-body ASMR experience of the sort that, otherwise, Nivedita only felt when listening to rain fall on gently flowing water, or looking at paintings by Amrita Sher-Gil, or smoking marijuana.

With a perfectly choreographed twirl Saraswati turned toward the class, lifted her glasses from her eyes, held them before her furrowed brow while the chain dangled from them, and scrutinised the student ranks now before her. ‘OK, let’s start: all whites out.’

Silence reigned as everyone wondered whether they’d heard right.

‘C’mon, let’s go, we haven’t got all day. Grab your stuff. You can come back next term. This seminar is for students of colour only.’

It was as if tectonic plates were shifting. Mountains rose up where before there had been empty planes. The earth burst open and something broke off the continent known as Nivedita, drifting out into an ocean of possibilities. ‘Umm, I say, that wasn’t in the course description,’ Lotte protested, as Nivedita marvelled at her tenacity, if not at her ability to assess dangerous situations.

Saraswati gave Lotte a good long look and, clearly amused, replied, ‘Is the word out really so hard to understand that you need me to spell it o-u-t for you?’

Without another word, Lotte gathered the pencil case she’d bought on Etsy and her Moleskine from the desk. The first bunch of grumbling students had already begun pushing their way out the door when a lithe girl with ivory skin – the shade a chain-smoking elephant’s tusk would have, that is – raised her hand.

‘Yes?’

‘Who counts as a student of colour? I mean, where do you draw the line?’ the young woman asked with audible uncertainty.

Saraswati clapped, ‘Excellent question! Who here feels that term applies to them?’

A few students hesitatingly stood up.

‘You can stay!’

Lotte also stood up, albeit with her pack all ready to go. ‘You coming?’ she whispered. The hurt visible on Lotte’s face pained Nivedita, but leaving would’ve pained even more.

‘I’m staying,’ she whispered back, and then quickly added, ‘for a bit,’ just to console Lotte.

‘But you’re white,’ Lotte said.

‘No, I’m not white,’ Nivedita said for the very first time in her entire life to a white person. She’d already tried convincing Priti, countless times, that she had just as much of a right to claim her mixed heritage as Priti herself did, since they’re relatives, after all (Seriously, Herrgottnochmal, or should she say Good Lord! Or maybe Hey Raam! …). Up until now, she’d never denied a white German their ostensible common ground. But there wasn’t a colonial army on the whole planet that could’ve kicked her out of this seminar.

She sure as hell couldn’t say any of that to Lotte, though, without hurting her even more. She might as well have just said ‘Babe, I belong to a club you can’t join.’ Even though Nivedita also had to admit that Lotte belonged to a ton of clubs that wouldn’t admit her. Like the club of girls who could charm everyone with their doe-eyed expressions – whatever it was Lotte was always expressing, since she was constantly deploying her doe eyes to get whatever she wanted. Like the club of girls who always went ‘home’ for Christmas, meaning ‘home to Hannover, Germany’s heartland.’ Like the club of girls who were always observing that the TV shows they watched every night had too few women in starring roles while at the same time failing to observe that the shows had too few melanated people in any roles.

Yet Nivedita always agreed with Lotte, of course, saying she too would love to see more female role models. Which is exactly why it was now so exciting to see one such role model swaggering at the front of class, before her very eyes, so close she could even touch her if she just clambered up onto her graffitied desk and reached her arm out. Maybe Saraswati wasn’t exactly strutting back and forth, but in Nivedita’s eyes she was too dynamic to just stand there and lecture.

‘Well now!’ Saraswati said, brimming with satisfaction as she closed the door behind the last white students to leave. ‘Let us begin. Why did you all stay?’ Nivedita’s throat swelled with silence, until she was sure all the words she’d never said would now cause her to burst. While her mind was still pondering precisely where to start, her mouth let loose, and out tumbled the story of Kali and the jungle, but this time it didn’t end ‘all the better to hug you with, my child!’ Instead, she heard her own voice saying, ‘all the better to rip your heart from your chest with, and then replace it with a stronger, better heart, my child!’

Saraswati gave her a good long look, about as long as the one she’d given Lotte earlier, and Nivedita considered grabbing her things and running after her flatmate, but then Saraswati asked, ‘What’s your name?’

‘Nivedita.’

‘Come by my office sometime this week, Nivedita.’

IDENTITTI

Why is Kali so cool? Let me count the ways:

She’s a goddess. I mean, where do you find goddesses any more? OK, that’s BS, there are actually tons of goddesses. (Can there be such a thing as enough goddesses? That’s a whole other post – stay tuned!) But do any of today’s dominant world religions venerate a goddess any more, not to mention the better question of whether any of these religions boasts so many damn goddesses that you can’t even count them?

She’s nude without being erotic. OK, that’s BS too, I actually think she’s super sexy. In her original form, Kali had not just one vulva, but hundreds. Scooch your cooch over, Venus! Kali’s eroticism isn’t the modest-maiden-standing-in-a-seashell-shieldingher-bosom-with-one-arm-while-crossing-her-legs-like-she’s-gotta-pee type. Nuh-uh. Kali’s nudity says: I can strangle a Bengal tiger with my bare hands, so watch out, or I’ll eat you for breakfast.

She’s dark. Yeah, Black. Sometimes she’s even dark blue or dark brown, and I’ve even seen a dark green Kali. But if there’s one thing she isn’t, it’s

white

.

She’s fierce and furious and drinks the blood of her slain adversaries. That’s how I want my goddesses. OK, that’s how I want

myself

to be: fabulous and frightening, inimitable and incalculable, and yeah, I’ll say it, I’d love to don a skirt of my enemies’ lopped-off arms. OK, OK, I’d much rather have no enemies whatsoever, because I’d be so frightening that nobody would dare mess with me.

During sex, Kali’s always on top.

‘During sex, Kali’s always on top,’ said Saraswati. ‘Why does that matter? After all, any old goddess can have sex absolutely any way she wants.’

I’m right on this, thought Nivedita, I’m right! The thought terrified her as much as it turned her on.

‘Because it’s not a personal preference, it’s a political choice,’ Saraswati said, answering her own question. ‘You all know the story of Snow White and the prince.’ With dramatic flair, she pointed her remote at the projector and the PowerPoint appeared. The first slide, taken straight from a classic edition of Snow White, showed a glass casket with a fairy-tale prince looming over it. The next slide had nearly the same composition, but this time the white, lifeless figure lying on the ground was the Hindu god Shiva, and Kali wasn’t looming over him, she was on top of him. Saraswati beamed her Kali-style smile at the class and continued: ‘Here we see dead Shiva. Shiva is a shava, meaning a corpse, because he chose to withdraw from the world as an ascetic. And it’s Kali who brings him back to life by … nope, not with a kiss … but …? That’s right, you guessed it: she ‘kisses’ him with her other lips. Which brings up a few other intriguing questions regarding consent, but we’ll get to that later in the term. For today, let’s focus on the fact that Kali refuses to be invisible. She forces Shiva to see her, to notice her, thereby forcing him to empathise with the world around him. So this myth is about recognising that everyone and everything has a soul, and that soul must be respected. It’s about love as a revolutionary act.’

Click, Mahatma Gandhi appears.

Click, Martin Luther King Jr.

Click, bell hooks.

Nivedita took notes like her life depended on it. Normally she doodled her way through lectures, sketching naked ladies all over her notebooks, every now and then jotting down keywords like social constructivism, brute facts, or, most recently, critical race theory. Saraswati was the first professor with whom Nivedita heard those terms appear in entirely new formulations, and that was because these sentences spoke directly to Nivedita, and that was because Saraswati’s sentences spoke directly about Nivedita.

‘And why is love a revolutionary act? Because it’s the first thing you teach people you plan to colonise-slash-oppress-slash-discriminate against: that they don’t belong, that they aren’t worthy of love,’ Saraswati continued, as Nivedita took it all down in her notebook. ‘And that’s meaningful because we only feel empathy for subjects worthy of love – hence, consequently, they are the only ones who can enforce their right to such empathy. It’s no coincidence that all groups and individuals who experience discrimination share a common sense that they’re less worthy, and worth less, than others. More specifically, that they don’t deserve as much love. “Nobody could ever love someone like me” isn’t a personal declaration stemming from a personal problem, rather it’s a social declaration pointing to a social problem. Of course a social problem can turn into a personal problem – but that’s a whole other issue. For today, let’s stick to structural problems.’

A girl in mustard-yellow glasses and a wax-print turban sitting next to Nivedita whispered anxiously, ‘I thought this was about racism …’

Nivedita whispered back, ‘Hey, this is about racism,’ and then wondered where her vehement tone had come from.

‘And that’s what’s so insidious about love, or the deprivation of love, used as political weapon: it doesn’t even have to be about a ‘real’ threat. The mere fear of losing love-slash-never being loved-slash-being loved less is enough to psychologically and even physically stunt people.’ Saraswati looked each student, one after the other, deep in the eyes. Several minutes passed before she continued, but nobody noticed, because they were all too busy reflecting on their own lack of received love. The girl who had just complained about the lecture not focusing enough on racism cried a single, sharply visible tear and made zero effort to hide it.

Throughout her relationship with Simon, Nivedita repeatedly returned to scan her notes from this very first seminar with Saraswati and thought: Fuuuuuuuck!

But in this very moment her only thought was: Wooooooow!

After establishing eye contact with every single student, Saraswati grabbed her book-laden leather briefcase and whipped out her bestseller at exactly the same moment as its cover image flashed onto the oversized screen. ‘Decolonisation means we have to decolonise not just business and politics, not just our theories and practices, but our own souls, too,’ she said while writing Decolonise Your Soul on the blackboard. ‘We can only behave with esteem toward other people of colour once we’ve internalised a sense of self-esteem. Before we can love our enemies, we first have to behave better with, and relate better to, our friends.’

In the toilets closest to the lecture hall, someone had scrawled ‘breasts not bombs’ on the wall, and someone else had added ‘Viva la Vulvalation!’ Nivedita took a selfie and thought about how she could put what had just happened into words. Maybe: Discovering Saraswati feels like being at a party thrown solely for us?

But even without her blog, her Twitter, and her Instagram, word about Saraswati spread like wildfire through all the secret channels that somehow always ensured that all the right people got all the right info. Over the following few weeks, more and more students of colour joined them, finding their way from other departments, even other universities. Saraswati was the only prof with a nose ring. Saraswati was the only prof who was Saraswati. Identity politics was huge, and Nivedita’s understanding of it was scant. And everyone was having a blast.

The only thing Nivedita knew was that, suddenly, she was someone – a person with a past and, consequently, perhaps even a future. She was no longer an absence, a blank page, a void within a space where childhood and adolescence were only conceivable in and envisioned for ‘German German’ families. Suddenly she was anecdotes and recollections and body memory, because suddenly her anecdotes and recollections had meaning – not to mention her body memory!

And that’s why Nivedita got busy, determined to collect as many new corporeal sensations and experiences as possible. Meaning: For the first time in her life, she got busy with men of colour.

Although she and they had always cautiously circled one another and then courteously avoided one another, each turning to white sex partners – be it out of fear they’d infect one another with their otherness, or out of fear they’d only discover they weren’t as special as they’d always been treated – now an entirely new buffet of sexual possibilities opened up: Are you homo, hetero, inter or intraracial?

For Nivedita, sex with other POCs meant putting herself on the market for the first time without her unique selling point. It was the first time she was really naked. It all came to a head when she fell in love with Anish, whose parents were both from Kerala – not like hers, who came from West Bengal and Poland and wherever. She was awaiting the inevitable moment he was bound to say: ‘You’re not really a real Indian.’

Instead, he said: ‘Sometimes I wonder what my parents see when they look at me. A potato?’

They were lying on the mattress in his room, the window wide open. The autumnal scent of asters wafted in, as did the dismayed cries of his flatmate, whose partner was closing the door on their relationship while literally leaving the window open for their breakup fight to be heard by all. As they lobbed insults at one another, Anish pressed his body against Nivedita’s as if she were the only one capable of saving him from the abyss of his own existence. The fact that Anish viewed sex with Nivedita as proof that he was who he thought he was acted as a powerful aphrodisiac. But am I who I think I am? She wondered.

2

‘You’re a coconut,’ someone had told Nivedita the first time she visited Birmingham, and she didn’t understand. Well, technically speaking, she understood every single word – but she didn’t get what that was supposed to mean. She didn’t even know which kid had said it first, but suddenly they were all saying it: Coconut! Coconut!

She was eight and it was summer – shimmering and glitzy as Art Stuff Glitter Lotion, bright as turmeric rice, perfumed as the scented coloured pencils she and her cousin Priti, who was thirteen months older, kept sharpening until only stubs remained, just to keep sniffing their synthetic smell. The shavings drifted down like ribbons onto the pavement behind the courtyard, accumulating on the hopscotch game drawn in chalk. The alley was dotted by a pile of pallets, a disemboweled old freezer chest whose tangled wires were hanging out, and a beat-up shopping trolley. All these random surfaces were crowned by kids sitting or squatting atop them – kids who all looked like Nivedita.

‘The kids there look like you,’ her mother had promised while packing a suitcase for their visit to the daughter of her dad’s oldest sister. There was a word for how they were related, something involving degrees, but Nivedita didn’t know what it was. All she knew was that her dad’s oldest sister was Didi – but that was her title, not her name, which was Purna – and her daughter was Leela … Nivedita still couldn’t really understand how the gorgeous, haughty woman in a flame-coloured sari who’d picked her up at the airport could be her cousin, even though she was old enough to be her mother, and that she had a daughter about the same age as Nivedita: Priti. So many names, so many intertwining family ties.

Auntie Leela, who was actually Cousin Leela, drove a mini car, but not an actual Mini, just a Vauxhall Nova. She was a doctor, but she wasn’t rich, because she worked for the National Health Service, and they lived in Birmingham, but Leela and Priti called it Balsall Heath. Or sometimes Balti Heath, because only Indian families lived there, and all these families had kids. It was like the whole world had suddenly turned brown.

‘We’re going home,’ Nivedita had told her classmates, not because she’d actually mistaken Birmingham for Bombay, let alone Kolkata, but because she, too, wanted to ‘go home’ for once, just like all her Turkish and Polish friends.

But in the snapshots her mother took of her and Priti and Priti’s little brother Aarul in Birmingham, it actually did look like they were in India. At least that’s how Nivedita always pictured India, chock-a-block with sofas and wall hangings decorated with so many little mirrored bits that they looked like someone had liberally spread them with the glitter body lotion she so adored. The first time she saw the pictures on her mother’s digital camera, she felt something expanding inside her, spreading out from her stomach, but she couldn’t quite name it – it was like a combination of warmth and something totally new to her, something unfamiliar, something like an almost triumphant feeling of belonging.

And so it was as if the voices coming from the alley lined by those pallets and the freezer chest, the voices whispering coconut, took that feeling and smushed it up into a tiny, seething-hot ball of shame.

‘Priti called me coconut,’ Nivedita said that night at dinner, although she said it in German for her mother’s sake – and to keep Priti from understanding. ‘What’s that mean?’

Her mother, Birgit, shot a quick glance across the dining room table at Priti, who calmly continued tearing her chapatis, indifferent. Birgit was wearing the blue sari Leela had given her, and looked a bit like the Virgin Mary – if Mary were ever to have inadvertently wandered into the Mahabharata – and for the first time, Nivedita noticed that her mother was white.

‘Oh, it doesn’t mean anything, sweetie,’ her mother brushed it off with a silly high-pitched giggle.

Nivedita thought about it a little while, and then disagreed: ‘If it didn’t mean anything, she wouldn’t have said it.’

Again, that silly giggle. Once Nivedita hit puberty, that giggle would fill her with a white-hot rage, making her so livid she wanted to knock it right out of her, no matter what it took. But on that particular vacation evening, as the setting sun cast its wistful rays through the window and then became one with the saffron-yellow walls, Nivedita hadn’t yet loaded her mother’s little laugh with any baggage – namely, years of conflict avoidance and evasion. That night, it just made Nivedita impatient.

‘What does coconut mean?’ she insisted. This time her voice wasn’t any louder, but it was more penetratingly shrill, and Priti looked up.

‘Maybe it’s because coconuts are hairy, and you have such long, beautiful hair?’ her mother ventured nervously, and Nivedita immediately became aware of her eyebrows, which were furrowing together over the top of her nose, as if to underscore why she’d never be chosen to play Maria in West Side Story, Baby in Dirty Dancing, or Elsa in Frozen for the school musical. Those roles were reserved for girls like her classmate Lilli, whose delicate, always-arched-in-surprise eyebrows made her look like a younger version of Lotte: Me? As Maria/Baby/Every-other-female-lead-you-could-ever-dream-of? For real?