3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

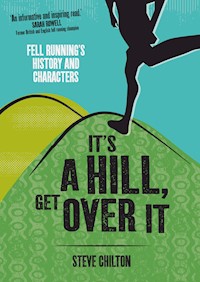

This book offers a detailed history of the sport of fell running. It also tells the stories of some of the great exponents of the sport through the ages. Many of them achieved greatness whilst still working full time in traditional jobs, a million miles away from the professionalism of other branches of athletics nowadays. The book covers the early days of the sport, right through to it going global with World Championships. Along the way it profiles influential athletes such as Fred Reeves, Bill Teasdale, Kenny Stuart, Joss Naylor, and Billy and Gavin Bland. It gives background to the athletes including their upbringing, introduction to the sport, training, working life, records and achievements. It also includes in-depth conversations with some of the greats, such as Jeff Norman and Rob Jebb. The author is a committed runner and qualified athletics coach. He has considerable experience of fell running, competing in the World Vets Champs when it was held in Keswick in 2005. He is a long-time member of the Fell Runners Association (FRA). Using a mixture of personal experience, material from extensive interviews, and that provided by an extensive range of published and unpublished sources, a comprehensive history of the sport and its characters and values is revealed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Praise for ‘It’s a Hill, Get Over It’

‘a really good read . . . A worthy addition to any fell runners’ bookshelf.’

Mud, Sweat and Tears

‘this exhaustive homage to fell running promises much, and delivers. Written with a real love for the sport’

Scotland Outdoors

‘Chilton clearly loves his subject . . . I learned much from reading it and I think it’s a book that many fell runners will really enjoy. Hopefully it will also inspire others who do not yet consider themselves a fell runner to venture out up a hill or two.’

Outdoor Times

‘a detailed history of the sport . . . a very informative read that will inspire those that read it to get out there’

Westmorland Gazette

‘An all-encompassing history of fell running to thrill and inspire you’

Trail Running Magazine

‘If you are interested in the history of fell running – written by a seasoned fell runner – then look no further. There are some brilliant photos here, not to mention an entire chapter on Joss Naylor.’

TGO (The Great Outdoors)

‘This story of how the sport’s foremost athletes developed is a fascinating one’

Scottish Memories

‘(a) must-buy publication for fans of mountain and off-road running’

Athletics Weekly

‘(Steve Chilton) covers the ground admirably, mixing the sport’s development over the last century and a half, largely in the Lakes, north of England and Scotland, the big races, and interviews and profiles of the big names like Kenny and Pauline Stuart, Rob Jebb, Fred Reeves, Boff Whalley, Sarah Rowell and more. And, of course, the man that’s “better than Zatopek, Kuts, Coe and Ovett” ... Joss Naylor.’

Cumbria Magazine

‘... is sure to please anyone with an interest in the noble sport of fellrunning’

Cumberland and Westmorland Herald

‘I was particularly interested in the references to orienteers who I did not know had fell running pasts … The one to one interviews brought the book to life, and generally highlighted the relaxed approach these people have to Fell running. The sections on Women’s running was interesting. We do take it for granted that life is much more equal now than in the past.’

Compass Sport (Britain’s national orienteering magazine)

Steve Chilton is a committed runner and qualified athletics coach with considerable experience of fell running, and a marathon PB of 2-34-53. He is a long-time member of the Fell Runners Association (FRA). In a long running career he has run in many of the classic fell races, as well as mountain marathons and has also completed the Cuillin Traverse. He works at Middlesex University, where he is Lead Academic Developer.

Steve’s work has been published extensively, particularly in his roles as Chair of the Society of Cartographers, and Chair of the ICA Commission in Neocartography. He is heavily involved in the OpenStreetMap project (osm.org), having co-authored OpenStreetMap: Using and Enhancing the Free Map of the World.

First published in 2013 in Great Britain and the United States of America:

Sandstone Press Ltd

PO Box 5725

One High Street

Dingwall

Ross-shire

IV15 9WJ

Scotland.

www.sandstonepress.com

This edition published 2014.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

© Steve Chilton 2013

© All images as ascribed

© Maps Steve Chilton 2013

Editor: Robert Davidson

Copy editor: Kate Blackadder

Index: Jane Angus

The moral right of Steve Chilton to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988.

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Creative Scotland towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-910124-17-8

ISBNe: 978-1-908737-58-8

Cover design and typesetting by Raspberry Creative Type, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Ozgraf, Poland

To mum and dad, who made me what I am, and would be very proud.

In many ways fell running has more in common with cycle racing than it does in other athletic events. The sport tests not only the competitor’s stamina but also his or her courage and skill as the runners descend at speed across uneven and often slippery surfaces. You might expect that coming down the slope they would pick their way gingerly as if descending stairs. Far from it. The minute they hit any section that is less than perpendicular, they immediately go flat out. At times this is just how they end up – flat out. The St John ambulance men are kept busy at fell races.

Harry Pearson in Racing Pigs and Giant Marrows

Lakeland fell runners are not ordinary men. Remarkable fitness and stamina are required to race up a fellside, and tremendous muscle control and judgement are needed to race down. Lakeland breeds such men, and has been doing since long before the days when records began to be kept at the local sports meetings.

Harry Griffin in Inside the Real Lakeland

Contents

List of Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Glossary/acronyms

Introduction

Chapter 1: Early days

Chapter 2: Professional versus amateur

Chapter 3: The Early Races – the 1800s

Chapter4: Development of a race calendar – the early 1900s

Chapter 5: Expansion of the calendar – the 1960s onwards

Chapter 6: Multi-day events

A conversation with: Helene Whitaker

Chapter 7: Some early giants

A conversation with: Tommy Sedgwick

Chapter 8: Administering the sport

Chapter 9: Ladies

A conversation with: Pauline Stuart

Chapter 10: Record breakers and champions

Chapter 11: The greatest – Joss Naylor

Chapter 12: Two more greats – Billy Bland and Kenny Stuart

A conversation with: Kenny Stuart

Chapter 13: Death on the fells

Chapter 14: Coming off the fells

A conversation with: Jeff Norman

Chapter 15: The Bob Graham Round

A conversation with: Jim Mann

Chapter 16: Some other fell challenges

Chapter 17: Going global

Chapter 18: Crossing sports

A conversation with: Rob Jebb

Chapter 19: Reporting the sport

A conversation with: Boff Whalley

Endnote

Postscript

References

Appendix 1 – Fell running and music

Appendix 2 – Course records

Appendix 3 – Fell running champions

Reference notes

Illustrations

List of Illustrations

John Greenop, winner of the Grasmere Guides Race 1876-1881A group of Grasmere Guides racers in 1876John Grizedale, Grasmere winner in 1888 and 1890J. Pepper (1st) and W. Barnes (2nd) after the 1893 Grasmere Guides RaceRivington Pike 1991. Mark Croasdale, Colin Donnelly, Paul Dugdale, Keith Anderson and Craig Roberts1958 LDMT winner Joe Hand (Border Harriers)The start of the 1957 LDMT from the Old Dungeon Ghyll; John Nettleton leadsJoss Naylor running in the Mountain Trial 1987The leaders on Red Pike in the Ennerdale race in 1985Helene Whitaker training above a misty EnnerdaleBill Teasdale, Tommy Sedgwick and Keith Summerskill at Kilnsey, 1970Tommy Sedgwick jumping a fence at Ambleside in 1982Tommy Sedgwick and Fred Reeves at Grasmere, 1973Fred Reeves celebrates winning Grasmere in 1974Fred Reeves leading Kenny Stuart at Grasmere in 1979Kenny Stuart leading from Mick Hawkins at Grasmere 1980Billy Bland and Pauline Stuart, 1980 Fell Runners of the YearPauline Stuart winning the Ben Nevis race in 1984Sarah Rowell winning the Three Peaks in 1991Angela Mudge at the Anniversary Waltz, 1999Billy Bland and John Wild, prolific record breakers, at Wasdale1994 Ben Nevis winner Ian Holmes in between Jonathon Bland on the left and Gavin Bland on the rightJoss Naylor on his 60 at 60 traverse in 1996Joss Naylor on Fairfield – in the 1999 Lake District Mountain TrialBilly Bland in the Ben Nevis race in 1984Kenny Stuart on Whernside on the way to winning the Three Peaks in 1983Kenny Stuart winning the Glasgow MarathonRossendale Fell Race – Jeff Norman leads Dave Cannon in 1970Phil Davidson, Bob Graham and Martin Rylands at Dunmail Raise, June 13 1932Billy Bland at the end of his record-breaking BGR in 1982 Rob Jebb leading from the Addisons on Reston Scar, 2012Rob Jebb leading from the Addisons on Reston Scar, 2012Alistair Brownlee leads brother Jonathan and Javier Gomez in the 2012 Olympic Triathlon in LondonPhoto credits

Prelim

Illustrated London News

Plate 1

Cumbria Libraries

Plate 2

Cumbria Libraries

Plate 3

Cumbria Libraries

Plate 4

Cumbria Libraries

Plate 5

Dave Woodhead

Plate 6

Lancashire Evening Post Ltd

Plate 7

Lancashire Evening Post Ltd

Plate 8

Pete Hartley

Plate 9

Pete Hartley

Plate 10

Helene Whitaker

Plate 11

Tommy Sedgwick

Plate 12

Tommy Sedgwick

Plate 13

Tommy Sedgwick

Plate 14

Cumberland and Westmorland Herald

Plate 15

Westmorland Gazette

Plate 16

Westmorland Gazette

Plate 17

Neil Shuttleworth

Plate 18

Dave Woodhead

Plate 19

Pete Hartley

Plate 20

Pete Hartley

Plate 21

Neil Shuttleworth

Plate 22

Ben Nevis Race Association

Plate 23

Colin Dulson

Plate 24

Pete Hartley

Plate 25

Neil Shuttleworth

Plate 26

Pauline Stuart

Plate 27

Pauline Stuart

Plate 28

Jeff Norman

Plate 29

Abraham Photographic

Plate 30

Copyright holder unknown

Plate 31

Mike Cambray

Plate 32

Moira Chilton

Maps

All maps in the book were compiled and drawn by the author. Map data is derived from the OpenStreetMap dataset which is available under an ODBL licence (http://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright). The contour data is derived from Andy Allan’s reworking of the public domain SRTM data (http://opencyclemap.org/).

Acknowledgements

There are many people to thank for various supporting roles in the production of this book. Firstly, I must thank Moira for understanding (I think) why sometimes I suddenly had to dash to the Lake District alone for the weekend to follow a lead, or why we had to interrupt our holiday to divert to some obscure café, only for me to say she must amuse herself whilst I interviewed someone she had probably never heard of.

When encouragement was much needed in the early days of the project Kirsteen Macdonald was usually available to massage the fragile ego of a nervous proto-author over a coffee. The Lake District trips often involved short stays at what I ended up thinking of as my writer’s retreat, to which Mike Cambray and family always welcomed me back.

I would like to thank various friends for the loan of their copies of Fellrunner and Up and Down magazines, and in particular to thank Nick Barrable for always willingly digging out back copies, or photocopies, of Compass Sport magazines or articles therein.

Almost any serious research will involve libraries to some extent or other, and this was no exception. To the staff of the British Library newspaper library in Colindale and the British Library in St Pancras I’d like to offer a huge ‘thank you’ for being there, and for providing such a superb service. I also spent many a productive day in Kendal public library, and really appreciated the support of the staff there, particularly Jackie Faye who helped source photographs and articles which I might never have found. The sweets that staff in the Local History section shared one day were part of what made working there such a joyous experience.

Many people have both helped trace photo reproduction rights, and then give them where possible (individual photos are credited as appropriate). Pete Richards, who is Keswick AC website guru, provided some seriously time-consuming help with tracking photo copyrights and providing important contacts. Pete Hartley, Dave Woodhead, Neil Shuttleworth, Colin Dulson, Tommy Sedgwick, Jeff Norman and Pauline Stuart also kindly searched out photos when leads took me to them and their photograph collections.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright owners, authors and publishers, and appropriate attribution to original sources has been noted.

I would particularly like to thank those who gave up their time to be interviewed, or check material in the draft of this book. I often felt that I was skating on thin ice, with just a book synopsis under my arm, and no previous ‘form’ as an author (which has got to be a pretty convoluted metaphor). A massive thanks to those I interviewed, for taking me at face value and for having faith in the outcome. I do hope I haven’t misrepresented any of you.

Then things started getting serious, and it was time to show someone the first draft of the manuscript. Celia Cozens was that first critical friend and she did a superb reviewing job. She made some significant structural suggestions and knocked some pretty rough edges off in the process, and still came back to agree to carry out a proof read for me later.

Especial thanks are due to my second critical friend, Alan Durant. He brought his considerable experience in the field to bear on my working manuscript. His comments resulted in a major structural and stylistic redraft which, I am sure, has resulted in a more readable book.

The completed manuscript was reviewed by the publisher’s own reviewers, who came back with some more suggestions for improvements. The final manuscript was then read by Sarah Rowell, and she provided a view from within the sport and some very useful pointers as to where I might have strayed slightly in my research. For this, and for providing a cover quote for the book, I am eternally grateful to her. John Blair-Fish reviewed a couple of chapters when I posed questions on topics in his field, and in the process helped me to correct some inconsistencies. Any remaining errors are mine.

Finally, I would like to express my grateful thanks to all at Sandstone Press, especially my editor Robert Davidson who has guided me patiently through the process of bringing this, my first book, to press; Kate Blackadder for her proofing skills; and Heather Macpherson for cover design, typesetting and organising the photo section.I would specifically like to thank the following for granting permission to quote passages from works written or published by them:

The Fell Runners Association for permission to use a number of quotes from their committee and AGM minutes.

Andy Styan, Ross Brewster, Harvey Lloyd, Alan Bocking, Tony Cresswell, John Blair-Fish and Rob Jebb for permission to quote from race reports they wrote for Fellrunner magazine.

The estate of Nan Shepherd and the publisher for permission to quote from The Living Mountain: A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland, Canongate Canons (2011).

Simon and Schuster for permission to use a quote from Boff Whalley’s Run Wild, Simon and Schuster (2012).

Aurum Press for permission to use three short quotes from Richard Askwith’s Feet in the Clouds, Aurum Press (2004).

Glossary/acronyms

AAA

Amateur Athletic Association

BAAB

British Amateur Athletic Board

BAF

British Athletic Federation

BGR

Bob Graham Round

BMC

British Mountaineering Council

BOFRA

British Open Fell Runners Association

BUCS

British Universities and Colleges Sport

carbo-loading

A carbohydrate-loading diet is a strategy to increase the amount of fuel stored in your muscles to improve your athletic performance. Carbohydrate loading generally involves greatly increasing the amount of carbohydrates you eat several days before a high-intensity endurance athletic event. You also typically scale back your activity level during carbohydrate loading.

CEGB

Central Electricity Generating Board

CFRA

Cumberland Fellrunners Association

CIME

Coupe Internationale de la Montagne

fartlek

Means ‘speed play’ in Swedish, is a training method that blends continuous training with interval training. The variable intensity and continuous nature of the exercise places stress on both the aerobic and anaerobic systems. It differs from traditional interval training in that it is unstructured; intensity and/or speed varies, as the athlete wishes.

ECCU

English Cross Country Union

FRA

Fell Runners Association

GR 20

A long-distance trail (Grande Randonee) that traverses Corsica diagonally from north to south.

IAAF

International Association of Athletics Federations

ICMR

International Committee Mountain Running

ITU

International Triathlon Union

KIMM

Karrimor International Mountain Marathon

LAMM

Lowe Alpine Mountain Marathon

LDMTA

Lake District Mountain Trial Association

LDSMRA

Lake District Search and Mountain Rescue Association

LAMM

Lowe Alpine Mountain Marathon

NCU

National Cyclists’ Union

NCAAA

Northern Counties Amateur Athletic Association

NIMRA

Northern Ireland Mountain Running Association

OMM

Original Mountain Marathon

OS

Ordnance Survey

PB

personal best (time) for an event

PYG track

The PYG Track is one of the routes up Snowdon. It is possible that it was named after the pass it leads through, Bwlch y Moch (translated Pigs’ Pass) as the path is sometimes spelled ‘Pig Track’. Or, maybe because it was used to carry ‘pyg’ (black tar) to the copper mines on Snowdon. Another possible explanation is that the path was named after the nearby Pen y Gwryd Hotel, popular amongst the early mountain walkers.

RWA

Race Walking Association

SHRA

Scottish Hill Runners Association

SLMM

Saunders Lakeland Mountain Marathon

Supercompensation

In sports science theory, supercompensation is the post training period during which the trained function/parameter has a higher performance capacity than it did prior to the training period.

SWAAA

Southern Women’s Amateur Athletic Association

UKA

UK Athletics

WAAA

Women’s Amateur Athletic Association

WMRA

World Mountain Running Association

YHA

Youth Hostel Association

Introduction

It was a lovely day on the fells. I was going up beside the wall on the steep side of Birk Knott when suddenly I collapsed to the ground and couldn’t go on. I gave myself a stiff talking to and struggled upwards. A friendly face, and a sugar rush from a proffered Mars bar, revived me enough to shuffle down the fell and complete the Three Shires Fell Race in a distinctly mediocre 2 hrs 53 mins 52 secs.

Earlier in the day I had pitched up at the Three Shires Inn full of bravado and looking forward to competing in this classic Lake District fell race. Facilities were limited, to say the least, and you mingled with the stars as you registered and submitted yourself to the required kit check. There was a rumour buzzing around that an Olympic champion had turned up to run. Was this to be my first victory over an Olympic champion? Turn up on the start line and you are there to be beaten, I reckon. OK, so beating the 1976 Olympic 400m champion Alberto Juantorena (so far the only athlete to win both the 400 and 800m Olympic titles) in the London Marathon a couple of years later may be no big deal, but you get the idea. (At least he had negotiated London’s kerbs better than he had the track kerb at the World Championships, where he injured himself by falling over it and ended his career.) Maybe Steve Ovett was turning to the fells to show an even more impressive range of distances and events than he had already achieved. Maybe Seb Coe was coming across the Pennines to show the value of all that hill work in the Rivelin Valley. Well no, it was Chris Brasher, some 32 years after he had won gold at the 1952 Olympics in the steeplechase.

The race started with a steady stream of runners ascending Wetherlam via the side of Birk Fell, then through Swirl Hawse to Swirl How. We then dropped down to the Three Shire Stone (marking the boundary join between former counties of Cumberland, Westmorland and Lancashire) on top of the Wrynose Pass. Then choices start to come into play. Ascending sharply up Pike of Blisco and choosing between contouring around via the road under Side Pike, or dropping south of Blea Tarn and facing the stiff ascent of Lingmoor Fell can make a lot of difference to your result. I had chosen wrongly, and faltered on the steep slope.

I wondered why I was suffering so badly. I was a reasonably conditioned marathon runner (with a PB (personal best) of 2 hrs 34 mins to come the next year) and, unlike my friends who would sit and watch Live Aid, I was to spend that weekend completing the two-day Karrimor International Mountain Marathon in the eastern Lake District. The winner that day completed the Three Shires in a time about an hour less than mine. Subsequently, Gavin Bland set the present course record of 1 hr 45 mins 8 secs in 1997. What I wanted to know was: how could these guys be so fast, what were they like, how did they train? More particularly, why was it that a bunch of guys called Bland, all from the same extended family from in and around Borrowdale, had set so many of the fell race course records in the Lake District (and other areas), many of which survive to this day?

Twenty-seven years later I set out to find out.

The particular questions I have drawn attention to above may not all be answered in the resulting book. My plans gradually changed as I started to undertake the necessary research. Over time, my project turned into a desire to go beyond such particular questions and to write a broader history of fell running. The end result is still, I hope, an in-depth study of fell running’s frequently neglected history. It is also now an account of some of the greats of the sport, as well as a description of some of the values which give the sport its distinctive character. Because of this broader scope, I felt it was best not to present the development of the sport chronologically, or through the vehicle of my own experience, or through the eyes of other runners. Rather, the sport’s historical development is explored more as a series of linked themes and topics, some but not all of which follow an overt timeline.

Fell running has, in my view, been poorly served by the publishing industry. Finding any books to read about the sport has always been a struggle, even in the best-stocked bookshops. The sport just hasn’t been that well documented. You could say that Bill Smith may have already written its definitive history, but a lot has changed since his influential Stud marks on the summits appeared in 1985. You might think Richard Askwith’s more recent Feet in the Clouds covers the sport’s history comprehensively, folded between the author’s own efforts in training and races, and finally his Bob Graham Round (BGR, see Chapter 15). Even Askwith’s journalistic, autobiographical examination is inevitably not a history of the sport. Boff Whalley’s still more recent Run Wild, another important book about what makes fell running the sport it is, is really a celebration, concentrating on what the author believes ‘running can be – unpredictable and surprising’.

Very few early books gave much guidance to those wishing to participate in the sport. James Fixx’s 1977 best-selling book The Complete Book of Running was for a while a huge influence on people taking up running. Fixx had a few words to say on the taking up of the sport:

Entering a fell race is simplicity itself … Training for the fells, on the other hand, is not so simple. More than once, runners who are acclaimed on the track have swaggered to their first fell race, only to be publicly humbled as their muscles turned to tapioca under the relentless punishment of the high places. Like runners everywhere, the best fell runners have their training secrets and superstitions. But there is at least one incontrovertible principle: To race well on fells you’ve got to do lots of training on them.

As we go through the history and the individual stories we will see how true this is, and also some variations on the training approaches that have been taken, even amongst the leading participants.

Bruce Tulloh’s The Complete Distance Runner was published in 1983, and offers a mere three paragraphs on fell running (note that like Fixx he is offering also a ‘complete’ coverage of running). Tulloh says of fell running:

This might be considered a form of cross country, but actually it is more of a religion. Some southerners maintain it is more of a disease, and that you will only take up fell running after being bitten by another fell runner, which is not unlikely, as they are a bunch of animals!

Later on, two publications appeared which covered training for fell running. Firstly, the British Athletics Federation published Fell and hill running by Norman Matthews and Dennis Quinlan in 1996, and then in 2002 Sarah Rowell’s Off-Road Running was published, which included examples of training programmes from well-known runners.

While acknowledging the excellent work of these authors, this book is an attempt to do something else. It brings together various facets of the sport, and looks at them from different perspectives. As successive themes and characters are explored, the book aims to give both a historical view and an idea of what participating in this fantastic and very different sport can offer.

A phenomenon as historically complex as fell running, and as relatively non-institutionalised, needs this kind of attention. I have written about many aspects: the people who run; the sport’s organisations and rules; its techniques and conventions; its dangers and rewards; and its relation to other apparently similar or closely related sports. The particular themes I have chosen range from the sport’s early days and domination by gambling and professionalism, through the development of a full race calendar, to the sport becoming ‘open’ at last. There are also details of the fight for control of the sport and of the development of international fixtures in recent years.

There is more to any sport than its competition element. I know of many participants in fell running, for example, who train but don’t ever race. They are happy just to enjoy the scenery and the mental and physical release running on the fells can give. There is much in my account of the sport for such people; but for those who do race, or who prioritise the competitive dimension, the book also includes detailed sections on championship winners, on course record breakers, and on the phenomenal endurance fell challenges that have been set, and beaten, over the years. Downsides of the sport are also touched on, like the fortunately infrequent fatalities, and individual or institutional disagreements.

Finally, fell running does not exist in isolation, and some coverage of the similarities and differences between fell running and marathon running, and those who succeed at both, is included. Similarly, those who compete at a high level simultaneously in fell running and in other related sports are discussed. Perhaps most important of all are the different kinds of participants in fell running: journeymen (and women), characters, record breakers, and innovators are all covered. Particularly highlighted for obvious reasons are the early giants of the sport, as well as those I consider all-time greats.

My mix of themes is brought together from a wide range of sources, both historical and contemporary. In order to present some important personal perspectives (other than my own) on what might otherwise seem a rather fact-laden read, I have spent a significant amount of time interviewing some of the sport’s leading proponents. Their reflections offer an interesting counterpoint to some of the recorded history. In some cases, their reflections even give a somewhat different slant to ‘facts’ reported in the published secondary sources. The gaps that open up should not be seen as revisionist, but more an acknowledgement that there are usually (at least) two sides to any story. If the resulting picture of some situation or event does not ring true to any particular reader, I can only say I have checked details with participants in such events as much as I possibly could. If any errors have crept in then mea culpa. Please feel free to contact me to discuss any such errors or omissions, and where I have an opportunity to do so I will correct them.

My background as the author of this book is both that of an academic and of a long-term participant in the sport of fell running. This isn’t an especially common combination, so it is worth exploring how I came into fell running and why I thought I should – and could – embark on writing the sort of account of the sport’s history outlined here.

My start came early, though not in an obvious or direct way. At school I followed an older brother who was academically very accomplished. At one point I was directly told by a teacher that I was ‘not as good as him’. That scarred me for life, but also got me going! My brother John was also an excellent cross country runner, so instead I took up race walking. I carried on playing football and eventually went to study a vocational (i.e. non-academic) course in cartography at Oxford Polytechnic. This period of my life is now recalled to others as ‘when I was up at Oxford’.

My father had run at a reasonable standard at school, and then played football. He was not especially sporty by the time I was growing up, although he was still a mainstay of his work’s sports club. He played cricket until fairly late in his life, and then continued in a managing and administrative capacity.

Finding my own way, I did the usual teenage stuff of going out exploring on foot and by bike, being brought up in the glorious Devonshire countryside. This was at a time when parents allowed their children to go about unsupervised all day long.

The day after my last exam in Oxford, a bunch of lads from the course threw sleeping bags and tents in a car and drove to Snowdonia. On day one we headed from the campsite at the north end of Llyn Gwynant straight up the flank of Gallt y Wenallt, something I probably wouldn’t do now as it was phenomenally steep and a wee bit scary. We were only young.

Several years of fell walking followed, getting more and more serious and including half-heartedly ticking off the Wainwright summits as they were done. A good friend, ‘Skipper’ Dave Allen, worked at Butharlyp Howe Youth Hostel and encouraged me also to go out running with him on the Lakeland Fells each time I visited. Occasionally this was in the company of Jon Broxap, who was a YHA warden at the time. There was no intention on my part to race – just to cover more ground. We also used to sit on the summits and take in the view.

Failing eyesight saw an end to football for me, and a consequent increase in girth due to some poor lifestyle choices at this time. Some friends were entering the Sunday Times Fun Run and this inspired me to get fit enough to do that. At a mere 2.5 miles it was no real problem. Chris Brasher’s instigation of the London Marathon in 1981 had also caught my imagination and I did a certain amount of training, and completed the event in a seemingly easy 3 hrs 5 mins. Four years of greatly increased training, facilitated by joining Barnet & District AC, gave me a PB of 2 hrs 34 mins 53 secs for the Marathon in 1985.

Soon after my 1981 marathon I had already started seeking new running challenges, and in that context the thought of fell racing came into my mind even though I wasn’t really in a position to do much decent fell training. No matter. My first race was Butter Crags, in June 1981. On that day I remember being especially impressed that one of the leading runners had gone straight back after the race to repair the wall where runners had awkwardly scrambled over it. Having enjoyed that race, I sought out similar fell races whenever I could, including most of the classic fell events. Joining the Fell Runners Association (FRA), I also followed the top-end of the sport closely, which was very competitive during that era – and I must admit I sometimes think back (possibly overly) fondly on the period as the best of times for the sport, with its uncomplicated race diary, amazing races and fast times.

Orienteering was also among my interests then, and led me to have the confidence to try some of the longer navigation events such as the OS (Ordnance Survey) Mountain Trial, the KIMM and the Saunders (as they were called at that time). One thing you do find out in taking part in the two person/two day mountain marathons is how you REALLY have to get on with your chosen partner – particularly when the going gets tough, usually on day two. Partnering with Mike Cambray turned out to be a good combination for me. I brought running fitness, whereas he probably had superior mountain craft – but amazingly we seemed to gel into a pretty efficient team. I can still recall the savoury pancakes he had made for one of our overnight camps.

I never achieved anything in orienteering, but enjoyed it immensely nevertheless. On reflection, I never achieved anything really in fell running. Looking back though I particularly enjoyed courses like the Fairfield Horseshoe the most: medium length and runnable. I kept going back whenever I could.

Time moves on. A hip replacement, which ‘may’ have been necessitated by years of hard training, put an end to racing. It was perhaps appropriate that my last race was the World Vets Fell Running Championships when it was held at Keswick in 2005. Running, in its own odd way, has led to writing. Some of the friendships made during my time in the sport became instrumental in making further contacts, which resulted in turn in interviews drawn on in this book. An informal network also built up of people only encountered recently, including some people only ever met virtually, and these people facilitated much of my research, gave access to further contacts again, and extended my ability to find previously unknown material sources and ownership of photo rights.

In the academic work that has paralleled my running career, I have written quite extensively on my area of expertise and interest (principally cartography). Writing this book has definitely been something completely different. I feel my passion for the sport and my academic instincts have jointly allowed me to produce a book that – I hope – strikes a balance between historical facts and the personalities behind them. I would like people both to appreciate the outstanding achievements of leading exponents of the sport and also to feel that fell running is something they could themselves enjoy, at some level or other from armchair to summit.

In writing this book it has also been my hope that it will go some way towards showing my appreciation for all the good times I have had on the fells, and will also serve as a thank you to people in the various networks I have identified who helped bring this material together. Perhaps the resulting work may find its place somewhere alongside the three outstanding books referred to at the beginning of this introduction, adding to the sport’s oeuvre and possibly inspiring others to write about their particular interests – exploring and reflecting on this sport or indeed on other subjects.

Chapter 1

Early Days

It’s a hill. Get over it.Seen on the back of a runner’s t-shirt

Fell running can easily be distinguished from other athletic events, in that it takes place not on a track or on roads but off road, over rough country and preferably with considerable amounts of ascending and descending, usually over some significant hills or mountains. There are organised fell races, certainly. It should not be assumed that fell running has to have a competitive element to it. Where there are races, they may also involve mountain navigation skills, since a race may involve participants finding their way from one checkpoint to the next, often over terrain that has no paths to guide the way. Thought of in this way, fell running is probably not a sport for everyone. It can give fantastic benefits, both physical and metaphysical, to those who take part.

There is much detail in this book of races, records and achievements. Not everyone sees it as being as competitive as that. There are those who are happy just being out in the fells. I certainly know of athletes who never take part in fell races, but who might call themselves fell runners, if asked. An interesting view on the competitive urge is expressed by Nan Shepherd in her excellent treatise on a life lived in the Cairngorms, The Living Mountain. She gives these thoughts on the matter:

To pit oneself against the mountain is necessary for every climber: to pit oneself merely against other players, and make a race of it, is to reduce to the level of a game what is essentially an experience. Yet what a race-course for these boys to choose! To know the hills, and their own bodies, well enough to dare the exploit is their real achievement.

She does admit on the very next page that it is ‘merely stupid to suppose that the record-breakers do not love the hills’.

Early feats of endurance such as those of the Greeks carrying news of victorious battles may at a stretch be seen as precursors. A traditional story relates how Pheidippides, an Athenian messenger, ran the 26 miles from the battlefield at Marathon to Athens to announce the Greek victory over Persia in the Battle of Marathon in 490 bc with the word ‘Νενικήκαμεν!’ (we were victorious!). He then promptly died on the spot. Being a messenger was a respected and well-rewarded occupation at this time. According to Thor Gotaas1, there was then no word for ‘amateur’, the nearest being idiotes, an unskilled and ignorant individual.

The story about Pheidippides is incorrectly attributed in most accounts to the historian Herodotus, who recorded the history of the Persian Wars in his Histories (written in about 440 bc). In its detail, the story seems improbable. The Athenians would have been more likely to send a messenger on horseback. Possibly they might have used a runner, as a horse could have been hindered by rough terrain encountered on the journey. It is difficult to be sure. Either way, though, no such story actually appears in Herodotus’ account.

As with the Athenians, there are also early records from Scotland of runners crossing the hills as the only way to spread urgent messages. Given the potential importance of such messages, clan chieftains organised races among their clansmen to find the fastest men to carry out the task. The details of their circumstances are highlighted in this excerpt by Michael Brander from his Guide to the Highland Games, where he notes that:

In the wild and mountainous highlands, where no roads existed, and peat bogs, boulders and scree were likely to slow down or cripple even the most sure-footed horse, by far the quickest means of communication was a man running across country. The ‘Crann-tara’ or fiery cross was the age-old method of raising the clansmen in time of need. It was made of two pieces of wood fastened together in the shape of a cross, traditionally with one end alight and the other end soaked in blood. Runners were dispatched to all points of the compass and as they ran they shouted the war cry of the clan and the place and time to assemble.

The earliest fell race that we have details of was that organised by King Malcolm Canmore (literal translation Big Head), who was King of Scotland in 1064. As a way of identifying suitable candidates for these message-delivering duties, a race up Creag Choinnich (or Craig Choinich), near Braemar, was put on by Canmore. The race was won by Dennisbell McGregor2 of nearby Ballochbuie. He received a prize consisting of a ‘purse full of gold’ and a sword. In a recent article about that race, in the Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal, Jamie Thin offers this description of proceedings:

All the challengers set off led by the favourites, the two elder Macgregor brothers, but at the last moment the third and youngest Macgregor brother joined the back of the field. The youngest brother caught his elder brothers at the top of the hill and asked ‘Will ye share the prize?’ The reply came back ‘Each man for himself!’ As they raced back down the hill he edged into second place and then dashed past his eldest brother. But as he passed, his eldest brother despairingly grabbed him by his kilt. But slipping out of his kilt, the younger brother still managed to win, if lacking his kilt!

It can be argued that McGregor was perhaps the best rewarded professional racer ever, if we take into account how minuscule the prizes in professional races were by comparison, even centuries later.

King Malcolm Canmore, it seems, had a more general love of sport, too. He had already earned respect for his hunting and fishing activities. Alongside his contribution to running in particular, his enthusiasm also helped create the forerunners of modern-day Highland Games in Scotland.

As well as the races to aid the search for messengers, there are more recent precedents, whereby endurance was both tested and admired. The exploits of nineteenth-century ‘pedestrians’ such as Robert Barclay Allardice, Corky Gentleman and the Flying Pieman provide some of the earliest formal endurance records.

One of the most famous pedestrians was Robert Barclay Allardice, who was known as Captain Barclay. He was born in August 1777 at Ury House, just outside Stonehaven in Scotland. He became the sixth Laird of Ury at the tender age of 17. Despite his noble upbringing, he was one of the strongest men of his generation, something which seems to have been a family trait. Members of his family were known for their achievements in activities such as wrestling bulls, carrying sacks of flour in their teeth and uprooting trees with their bare hands. J.K. Gillon wrote of Barclay3:

In 1809, at Newmarket he accomplished his most noted feat of endurance walking. This involved walking one mile in each of 1,000 successive hours. In other words Barclay was required to walk a mile an hour, every hour, for forty-two days and nights. Barclay started on the 1st June and completed his historic feat on the 12th July. His average time varied from 14 minutes 54 seconds in the first week to 21 minutes 4 seconds in the last week. Over 10,000 people were attracted to the event and Barclay picked up substantial prize money for his efforts. Variations on the ‘Barclay Match’ were attempted throughout the century.

Wagers on the feat were estimated at around 16,000 guineas (valued at over half a million pounds today)4. In 2003 a team re-created the 1,000 mile challenge, and finished it off by running the London Marathon. They achieved the 1,000 mile target easily. However, when it came to running the marathon they struggled because they had actually lost fitness during the event.

Despite being famous for pedestrianism, Barclay was also acknowledged as an accomplished stagecoach driver. He is credited with taking the London mail coach to Aberdeen single handed, which required considerable endurance, as he had to remain seated for three days and nights. Captain Barclay died of paralysis in 1854, a few days after being kicked in the head by a horse as he tried to break it in.

It wasn’t just the British that took up pedestrianism. In 1879, an American called Edward Weston was mobbed by so many British fans that he fell just short of completing a 2,000- miles-in-1,000-hours walk around England. Along the way he delivered lectures about the health benefits of walking. He was given a police escort whenever he went into major towns and cities in his trademark hat and boots. His career stretched over 61 years, from 1861 to 1922. He was a star on both sides of the Atlantic, at a time when pedestrianism was a sport which hundreds of thousands of people turned out to watch, and he was the focus of the betting of huge sums of money.

Weston’s endurance capability and remarkable powers of recovery led doctors to study what he ate and how much he slept, even taking samples of his urine and faeces. It was during those studies that one of the most controversial parts of Weston’s career came to light. Doctors noticed a brown stain on his lips after a race and discovered it was down to his chewing of a coca leaf, the source of cocaine. The incident is one of the first known examples of drugs being used to enhance sports performance.

When he died in 1929 Weston was 90 years old. At that time, the life expectancy for males in the US was just short of 56. During the last two years of his life, though, he was in a wheelchair, after being hit by a modern invention that he considered something of an enemy – the motor car.

Returning to the earliest recorded foot races, there are stories of competitors being naked. Similarly, the earliest Olympians supposedly competed in the nude, adorned only with olive oil. Personally, I can’t imagine how I would deal with the distraction of un-restrained ‘equipment’ when trying to run a race. I still have all too vivid memories of spectating at a cross-country event when a clubmate had to pull out when leading the race, due to a clothing malfunction opening him up (literally) to a possible charge of indecent exposure.

Imagine then the scene described in Miss Weeton: Journal of a Governess, 1807-1811:

there followed a foot race by four men. Two of them ran without shirts; one had breeches on, the other only drawers, very thin calico, without gallaces [braces]. Expecting they would burst or come off, the ladies durst not view the race, and turned away from the sight. And well it was they did, for during the race, and with the exertion of running, the drawers did actually burst, and the man cried out as he ran ‘O Lord! O Lord! I cannot keep my tackle in G-d d-n it! I cannot keep my tackle in’. The ladies, disgusted, everyone left the ground … it was a gross insult to every woman there.

There are also other early endurance running exploits to be noted outside the United Kingdom. There used to a saying ‘to run like a Basque’. At the end of the eighteenth century the mountain dwellers from the Basque region used to hold two-man races, around which much betting took place. They favoured fairly long distances, anything from six miles to around 15 miles. The events were not held over fixed routes, but had fixed starts and finishes. The participants developed excellent fitness, navigation and resourcefulness as they negotiated the very hilly courses used for these events.

Some running ‘characters’ were also appearing in the New World. The Flying Pieman was the nickname of William King, who was born in London in 1807. He emigrated to Australia in 1829, landing at Sydney. By 1834 he had begun cooking and selling meat pies around the Hyde Park cricket ground and along Circular Quay. He was known as ‘The Flying Pieman’ because of the practice whereby he offered his pies to passengers as they boarded the Parramatta steamer. He would then run the 18 miles to Parramatta with the unsold pies, and offer them to the same passengers as they disembarked. He also twice managed to beat the Sydney to Windsor mail coach on foot, a distance of just over 32 miles.

Moving on through history, we see that organised fell running has its real roots in the mid nineteenth century. It was in northern England that fell races started being established in the mid-1800s. The first races as we know them now were those that were incorporated in local events, being just another test of physical prowess. They would take place alongside events such as wrestling, sprinting and throwing the hammer or tossing the caber (a Scottish speciality). In Scotland, the community aspect was borne out by the cultural and agricultural activities that were taking place on these occasions, which were more akin to the fairs or agricultural shows in England. Fell running has developed into one of the toughest branches of athletics, with its emphasis on endurance and rough terrain.

Two of these earliest local events were held in Yorkshire, at Lothersdale in 1847 and Burnsall in 1850. In the Lake District the Grasmere Sports were first held in 1852, incorporating a fell race (the now famous Guides Race), as well as Cumberland- and Westmorland-style wrestling and hound trailing. The term ‘guides’ stemmed from the experienced fellsmen, such as fox hunters and shepherds, who guided the early-nineteenth-century tourists engaging in lengthy walks and explorations in the mountains. In the early days these ‘guides’ were often the only fell race contestants, as they raced to prove their superiority, and thus enhance their employment prospects. The races were virtually exhibition events staged for the guides to display their fell racing talents to appreciative gatherings at the shows. Sometimes they took the form of handicap foot races around an undulating course.

In Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes he describes an excursion to the top of Scafell with a shepherd guide, and he is later recorded as watching fell racing. One of the most famous of the early guides was Will Ritson, who was landlord of the Wastwater Hotel (now the Wasdale Head Inn) in Wasdale, and noted for his tall tales. He has a bar named after him in the pub, and is the inspiration behind the World’s Greatest Liar competition5.

In some cases cycle racing also featured intermittently in the programmes. Having watched grass-track racing at sports meetings I can see a certain similarity with chariot racing, with their tight circuits. Furthermore, looking at the old photos of events like Grasmere you can imagine a gladiatorial aspect to the cycle events with their tightly packed large crowds pressing in on the oval arena. The early fell races were designed for the benefit of spectators, and were usually held over a direct course encompassing fields, walls, streams and whatever obstacles were around. They usually led to a tough climb up the adjacent fell or crag as far as a prominent marker point on the skyline and then straight back down again.

Like Wordsworth, Dickens was known to have attended these festivals, which were held in places like Windermere and Ambleside, as well as at Grasmere. In Ambleside it was the Cycle Club which originally promoted the first Ambleside and District Amateur Athletic Sports in 1892. The organisers proudly declare on the event website6:

Many events with our type of location have switched to mountain cycling, however here at Ambleside we have retained track cycling around a 300m circuit which ensures that the sport remains exciting for the spectators. Both the Senior and Junior events are also handicapped which helps to ensure that every race is closely contested.

There had been an Ambleside Sports held in 1886 to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. Although there seems to be no evidence in contemporary reports of a fell race, the event was repeated in 1887, and a fell race is noted. There appear to have been no sports for four years until the aforementioned Amateur Athletic Sports were held in 1892. These were held under the then current cycling and athletics rules, and the committee banned professionalism and gambling of every description. However, prizes to the value of £35 were donated by local tradesmen (worth well over £2,000 today).

Details of these events now started to appear in historical records. One such example is Marjorie Blackburn’s booklet Our Traditional Lakeland Sports, which documents Ambleside and its Sports in fascinating detail. In it she notes, with regard to the fell race of 1892:

for this there were 14 entries, but only about eight started. The course should have been across the river, and over the two highest peaks at the Ambleside end of Loughrigg, but owing to the floods it was deemed risky to cross the beck, so the course lay out of the field over the two bridges and up by Brow Head. Prizes: 1 – tea service, value £2 [£119]; 2 – castors, value £1 [£59]; 3 – opera glasses, value 10s [£30].

However, there is some uncertainty around the exact origins and dates involved in events like Grasmere being established. One account is given in Reminiscences in The Life of Thomas Longmire. Here J. Wilson (referring to Grasmere) wrote:

It is somewhat difficult to arrive at the exact time when these noted sports were really established, as they emanated and gradually developed from the old rustic wrestling contests, for most insignificant prizes, which were inseparable from the annual Sheep Fair, held on the first Tuesday in September ... As the Guides Race is the most popular feature of the programme, that may be taken as the foundation, and was started at the September Fair in 18697 held under the stewardship of Mr W.H. Heelis and Mr J.F Green, and it is mainly due to the last named gentleman, that the Grasmere meeting has attained the proportions and popularity it has done, and of which he still is, and has been from the first, Honorary Secretary and Treasurer. There were 10 entries in the first Guides Race won by G. Birkett, with W. Greenop the ‘Langdale antelope’ second.

The next year saw the establishment in Scotland of the New Year Sprint, which is one of the longest standing athletics events in the UK. The Sprint has been staged in Scotland on or around New Year’s Day every year since 1870. It is a handicap race over 110 metres. Competitors, whether amateur or professional, now race for prize money totalling over £8,000.The New Year Sprint, formerly known as the ‘Powderhall’, is a unique event, as it represents the last of the old galas. The format, however, remains unchanged. Races are handicapped to try to ensure close finishes, and betting adds to the enjoyment of the spectators.

The prizes at these early events might have generally been insignificant, but the betting was serious and that produced many issues. Both the pedestrians and the sprinters were embroiled in a world of gambling, which they shared with early fell runners. The days of huge betting coups and malpractice are long gone, but the tradition, spirit and atmosphere remain. It is still a big deal to win the ‘Big Sprint’.

One particular event of this era achieved great notoriety. ‘The Race of the Century’ was how the newspapers of the day billed the world championship challenge race between Harry Hutchens and Henry Gent in 1887. With 15,000 spectators packed into West London’s Lillie Bridge stadium, the two runners were forcibly removed from the dressing-room, bundled out of a side-entrance and spirited away in separate carriages. When their non-appearance was announced, the crowd tore down the wooden stadium buildings, ripped up the perimeter railings and burned everything that they could get their hands on. The spark, it transpired, had been the bookmakers being fearful of being cleaned out after discovering that Gent had broken down in training. ‘They stood over me in the dressing-room with open knives and bottles,’ Hutchens told The Sporting Life. ‘They swore they would murder me if I tried to run.’ The burning of Lillie Bridge prompted the demise of pedestrianism, but not gambling and professionalism. The stadium had been the venue for the early ‘Varsity’ athletics match between Oxford and Cambridge Universities, which had been held at Lillie Bridge from 1867 to 1887.

The earliest fell races were invariably professional, in that the winners were awarded cash prizes. The first prize might exceed a week’s wages and at a major meeting, such as Alva, far exceeded it. The races also attracted bookmakers and gambling. By the 1911 Ambleside Sports betting was allowed quietly (‘and no shouting by the bookmakers’). The continued influence of the bookmakers at the sports meetings may be judged by Marjorie Blackburn reporting in Our Traditional Lakeland Sports that as recently as in 1981 there was a serious problem when:

all four hound trails had to be called off after reports off sheep worrying in the Cumberland Fells. A hound, which had gone missing two months previously was thought to be the culprit. On the day of the Sports the bookies, not to be outdone, bought in portable TV sets to cover the afternoon’s horseracing.

There was also unfortunately sometimes malpractice in evidence, because of the betting involved. One such example is noted by rock climber Ron Fawcett8 in his autobiography Rock Athlete:

Fell running is in my blood, in a way. Grandad Bate was a good runner in his youth, and locally very successful ... There is a big race in Embsay, every year in September, and a story in the local press had tipped Grandad as worth a few quid at favourable odds. So a local bookie headed off a possibly disastrous day for the bookmaking fraternity by getting Grandad drunk. Needless to say he didn’t win.

The pecuniary rewards available were considered immoral by the ‘gentlemen’ supporters of the amateur concept, and when the (AAA) Amateur Athletic Association9 came on to the scene their objective was to rid athletic sport of this influence, causing other problems on the way, as we will see. The history of some of the earliest races is included in Chapter 3, but first we look at the professional/amateur divide, which at one point looked like ripping the sport apart.

Chapter 2

Professional versus amateur

Training can get on a man’s nervesAlf Shrubb

It can be quite difficult to get a clear picture of the amateur and professional divide in the sport of fell running, as often the lines have not been clearly drawn. The sport has moved from being dominated by professional races, through two parallel codes, to now being an integrated open sport. In the early days the professional races tended to be shorter, and the rise of the amateurs increased both the number of, and range of lengths of, races that were being organised.

Confusion reigned at times. For example, the 1877 and 1878 Grasmere Guides Races were contested by professionals alongside amateurs, although the formation of the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) ended that practice. At Grasmere in 1878 there were two competitions run in parallel over the same course. For the professional event there were only three starters, and for the amateurs eleven. The report quoted in See the Conquering Hero Comes lists the three professional finishers as J. Greenop, W. Greenop and W. Scott, with the comment that:

the race altogether was a fair one especially between J. Greenop and Warburton, the latter of whom is a well-known amateur athlete. He did not know the course and this was a great disadvantage, he, however held his own well in making the ascent, and in coming down, was only some 40 yds behind Greenop who won in 16 min 31 secs. Some of the others who had been toiling up the steep ascent, had scarcely reached the summit when the leaders were topping the wall on their return.

The Grasmere Guides Race was first held in 1868, going to the top of Silver Howe and back. It was a professional race, with £3 (£137