Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

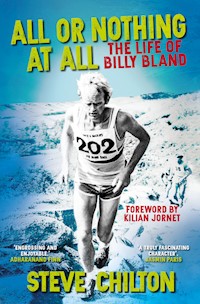

Billy Bland set fellrunning records in the 80s and 90s while working at quarrying, building and stonewalling in his native Borrowdale. His 1982 Bob Graham Round record stood until 2018 when it was, at last, surpassed by the phenomenal Kilian Jornet. First and forever though, he is a champion of his beloved Lake District and the people who live there.Filled with stories of competition and rich in northern humor, All or Nothing At All is testimony to the life spent in the fells by one of their greatest champions, Billy Bland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 572

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALL OR NOTHING AT ALL

The more you do, the better you get.

By the same author

It’s a Hill, Get Over It

The Round

Running Hard

First published by Sandstone Press Ltd

Suite 1, Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

© Steve Chilton 2020

© Maps Steve Chilton 2020

© Chapter illustrations Moira Chilton 2020

© Photographic plates as ascribed

Editor: Robert Davidson

The moral right of Steve Chilton to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-913207-22-9

ISBNe: 978-1-913207-23-6

Jacket design Raspberry Creative Type, Edinburgh

Ebook compilation by Iolaire, Newtonmore

To Penelope and Kerena,

the next generation

CONTENTS

List of chapter illustrations

List of photographic plates and credits

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Kilian Jornet

Preface

Chapter 1 Growing up

Chapter 2 My hometown

Chapter 3 Seeds

Chapter 4 Man’s job

Chapter 5 The rising

Chapter 6 Reason to believe

Chapter 7 Man at the top

Chapter 8 The ties that bind

Chapter 9 Glory days

Chapter 10 Tougher than the rest

Chapter 11 Further on up the road

Chapter 12 When you need me

Chapter 13 This hard land

Chapter 14 Across the border

Chapter 15 No surrender

Chapter 16 It’s my life

Chapter 17 Real world

Chapter 18 Land of hope and dreams

Chapter 19 Living proof

Chapter 20 Long time coming

APPENDIX Definitions of fell race categories

References

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Nook Farm: where Billy Bland was born

2. Farm equipment: an old hay wagon

3. Latrigg: location of Billy’s first ever race

4. Honister Crag: location of the mine that he worked at

5. Scafell Hotel: from whence his amateur first race win starts

6. Ashness Bridge: on one of his favourite training routes

7. The Bad Step: on the classic Langdale race route

8. Thorneythwaite Farm: twice in the Bland family

9. Scafell Pike: on the Wasdale race route

10. The Moot Hall: where the Bob Graham Round starts

11. Great Gable: which is on the Borrowdale race route

12. Keswick High Street: where the Bob Graham Round finishes

13. Buttermere: valley where one of Billy’s last races was held

14. Mount Cameroon: one of Billy’s race locations abroad

15. High Street: on a race that Billy never won, Kentmere

16. Mountain View: the Blands’ house

17. Borrowdale Institute: a community hub and race venue

18. The Bowder Stone: a distinctive Borrowdale feature

19. Castlerigg Circle: legacy in the landscape

All line drawings in the book were drawn specially for the book by Moira Chilton, and are not to be used without prior permission.

LIST OF RACE ROUTE MAPS

Borrowdale race

Langdale race

Ennerdale race

Kentmere race

Wasdale race

The Bob Graham Round

Edale Skyline race

Fairfield race

Three Peaks race

All maps in the book were compiled and drawn by the author. Map data is derived from the OpenStreetMap dataset which is available under an ODBL licence (http://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright). The contour data is derived from Andy Allan’s reworking of the public domain SRTM data (http://opencyclemap.org/).

LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHIC PLATES

1. The Blands at Borrowdale School, 1954. [Billy 2nd row, 4th left; Stuart 3rd row, 2nd right; David 2nd row, 7th left; Ann 1st row, 2nd right]

2. Billy Bland, aged about 8

3. Lairthwaite school football team, 1959 [Standing, 2nd right: Howard Pattinson; Seated, 2nd right: Billy Bland]

4. Billy winning his first pro race at Patterdale in 1967

5. Braithwaite football team, 1970 [Billy: back row, 2nd left]

6. Billy heads Mike Short at the Blea Tarn road in the Langdale race, 1976

7. Goat Fell, Arran, 1979 [Duncan Overton 2nd; Andy Styan 1st; Billy Bland 3rd]

8. Keswick AC’s winning team at the Northern Counties fell champs, 1979 [Anthony Bland, Billy Bland, Bob Barnby]

9. Fellrunners of the year, 1980 [Billy Bland and Pauline Haworth-Stuart]

10. Billy’s trophy haul from the 1980 season when he was Fellrunner of the Year

11. Saunders Lakeland Mountain Marathon, at the end of Day 1, 1981 [Race partner Stuart Bland is out of shot]

12. Training at the top end of Borrowdale, 1981

13. Posed photograph for an article on the BGR record that was published in the Daily Express

14. With John Wild after the 1982 Wasdale fell race

15. Two of Billy’s training partners, Dave Hall and Jon Broxap – racing at the Blisco Dash, 1983

16. Leading Hugh Symonds in the 1983 Blisco Dash

17. Chris Bland and Billy taking a break from work

18. Descending at Ben Nevis, 1984

19. Survival of the Fittest on TV, 1984

20. Stuart Bland and Billy Bland supporting a BGR, 1984

21. Running for Britain, Causey Pike, 1985

22. Checking the rain gauge, up above Seathwaite

23. Winning at Wasdale, 1986

24. Buttermere Sailbeck, 1987

25. At the Three Shires race, 1987

26. Billy Bland and Rod Pilbeam – finishing leg 1 at the Ian Hodgson Relay, 1987

27. Andy ‘Scoffer’ Schofield at the 3 Peaks race, 1988

28. Billy Bland at the Langdale race, 1990

29. Gavin Bland at the Ian Hodgson Relay, 1991

30. Near the start of the Langdale race in 1991, Billy Bland in eighth place

31. Borrowdale Fellrunners – FRA Team Gold, 1993 [l. to r. Gavin Bland, Billy, Scoffer, Steve Hicks, Simon Booth, Jonny Bland]

32. Billy Bland – Ian Hodgson Relay, 1995

33. A Mackeson at Wasdale on the BGR record, 1982

34. Support at Wasdale, BGR record

35. Record Bob Graham Round, 1982, setting off up Kirk Fell with Joss Naylor

36. The run-in, on the road in Newlands Valley on the BGR record

37. Celebrations on the Moot Hall steps on beating the BGR record [From left: Fred Rogerson, Chris Bland, Pete Barron, Jon Broxap, Stuart Bland, Martin Stone, Billy, David Bland, Joss Naylor]

38. Reflecting on his new BGR record, at the Moot Hall

39. Billy’s ratification sheet, with pacers and timings, for the BGR record, 1982

40. Moffat Chase, 1987

41. Ian Hodgson Relay – Billy Bland & Pete Barron, 1988

42. Climbing out from Honister, supporting Boff Whalley’s BGR [l. to r. Boff, Mark Whittaker, Billy, Gavin Bland]

43. On his multiple cycle trips up and down Honister Pass in 2014

44. Kenny Stuart, Joss Naylor and Billy Bland share a stage, and a laugh, Brathay 2016

45. Susan Paterson and Billy Bland, bike racing for GB, 2017

46. Encouraging Kilian Jornet on his new record BGR, at Dunmail Raise 2018

47. Previous and new BGR record holders on the Moot Hall steps, 2018

Photo Credits

All from the Billy Bland Collection, except:

Cover: Neil Shuttleworth

Plate 4: Robert Armstrong

Plate 7: V. B. Shaw

Plates 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 31: Neil Shuttleworth

Plates 15, 16: Dave Woodhead

Plate 22: Lakeland Photographic

Plate 24: Steve Bateson

Plates 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 32, 41: Pete Hartley

Plates 33 and 35: Martin Stone

Plate 40: Allan Greenwood

Plate 42: Boff Whalley

Plate 43: David Woodthorpe

Plate 44: Martin Campbell

Plate 45: Mark Wilson

Plate 46: Danny Richardson

Plate 47: Pete Barron

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are always many people to thank when producing any book, and this is no exception. First and foremost, I must acknowledge Billy and Ann Bland, without whose cooperation the project would have remained just an idea. Billy Bland, whose very aura and reputation worried me at the start of this journey, proved to be a very charismatic subject. He was endlessly polite and honest, however personal my probing became. He always tried to say it like it was and has always produced great quotes when interviewed by myself or others. Ann Bland supported Billy, and myself, all the way. She prompted Billy if memory temporarily failed him, responded to my interminable follow-up queries, and proved herself to be the rock that she has been for him all their life together. My many visits to the top end of Borrowdale to talk with them both have been pivotal in telling this story, and it has always been a pleasure to discuss the old and recent times with them.

As well as Billy and Ann, I have also had some in depth conversations with several contemporaries, friends, family and rivals. To the following in particular I give my heart-felt thanks for finding the time to answer my sometimes naïve questions: Pete and Anne Bland, Pete Barron, Jan Darrall, Jon Broxap, Colin Donnelly, Howard Pattinson, Ross Brewster, Mark Wilson, Hugh Symonds, Kenny and Pauline Stuart, Joe Ritson, Tony Cresswell, John Wild, Gavin Bland, Dave Hall, and Scoffer Schofield.

Help comes in many different ways. For finding and suggesting various reference sources I turned to Jeff Ford and Charlotte McCarthy (both from the Mountain Heritage Trust), the latter inviting me to look through material at the Trust library, where I also bagged some mountaineering book bargains as they were clearing out some unwanted stock. I also received some good leads from Julie Carter (author of Running the Red Line) and Joe Ritson, who followed a great chat at the Keswick Museum café with some really useful material from his own archive. Martin Stone was instrumental in connecting me to Kilian Jornet, who generously agreed to write the Foreword to the book.

That thing called the internet is also wonderful for finding contacts and resolving queries. So, thanks to diligent folk on the Fell Runners UK Facebook group and the FRA Forum for responding to my random requests for info, race results, or other trivia. For furnishing me with contact details for people that I wanted to speak to I am particularly grateful to Matt Bland, Chris Knox, Hugh Symonds, and Ann Bland. In a similar way I needed to refer to some Fellrunner magazines that I didn’t have (and weren’t on the brilliant FRA website archive) and both Marcus Covell and Simon Blease kindly offered to send me missing ones that they had and were prepared to donate to aid my research.

Let us not forgot the value of librarians. On several visits to the excellent Kendal Library Local History section Kate Holliday and Sylvia Kelly were invariably welcoming, and happy to search out my obscure reference requests from their stock. Equally valuable was the support I received from Vanessa Hill, of the Middlesex University Library, who tracked down (and sent me) some references when I was looking into re-wilding and specifically the Wild Ennerdale project. I have also done much reading around the subject as I have been writing the manuscript, and the main books and other resources referred to are listed in the references section.

Huge thanks are due to the following for help in sourcing photographs from their own collections and archives, and for giving permission to use them in the book: Pete Barron, Steve Bateson, Allan Greenwood, Denise Park, Neil Shuttleworth, Martin Stone, Boff Whalley, and Mark Wilson.

A writer always benefits from the support of friends, whom they can tire out with stories of how badly, or well sometimes, the manuscript is going. Among such friends one who stands out is Mike Cambray, who was always happy to accommodate me on dashes to the Lakes, and act as a sounding board for my ideas regarding this project. On one walk through his local Craggy Woods he came up with the brilliant suggestion of illustrating each chapter with a line drawing relevant to the part of the story within it. Moira Chilton somewhat nervously took on the task of providing the pen and ink illustrations which introduce each chapter. I hope you will agree that they are marvellous, helping set the scene and giving an excellent locational context to the journey.

On the many journeys to interview people for the manuscript Bruce Springsteen has many times been my companion. He has been the soundtrack to my writing and researching and is an inspiration to me on several levels. I once listed his ‘Born to Run’ in a blog on my favourite running books. It is actually the best written rock autobiography, in my opinion. The discerning reader/rock fan may detect his tangible presence in this tome.

At some point an author has to show their work to someone, ideally someone who is willing to read it and give constructive feedback. Massive thanks go to Ed Price for being my critical friend, despite having a very busy domestic and working life himself. He made some very sound suggestions regarding structure and style when reviewing the first draft of the manuscript for me, and I am sure the subsequent re-drafting has produced a better and more readable result. Any errors in the script are of course my responsibility.

Thanks to my editor Robert Davidson, proof-reader Joy Walton, cover designer Heather MacPherson of Raspberry Creative Type, indexer Roger Smith and all at Sandstone Press who, as always, have been a pleasure to work with.

FOREWORD

by

Kilian Jornet

When I came to England to consider doing the Bob Graham Round (BGR) I was very keen to meet Billy Bland, but also unsure about how a meeting would go. He is a legend and I had been told that he doesn’t particularly like non-fell runners coming to run the fells.

Nervously I knocked on the door. I was somehow pleased when Ann, his wife, said that he wasn’t at home. He was out for a ride on his bike and she wasn’t expecting him to be home for a few hours. ‘He likes biking now,’ Ann explained. I could comprehend that for someone as compulsive and addicted to sport as Billy Bland that it didn’t just mean that he’d take an hour bike ride twice a week, even in his 70s. I came back the day after, and Billy was home this time. We discussed me doing the BGR for a fair while, and early on he asked me, ‘are you going to use poles?’. I said no. ‘All right,’ he said. Real fell runners don’t use poles, apparently. We talked for ages, and he explained to me how he ran the Bob Graham Round nearly 40 years ago. It was in a time nobody has come close to since. He told me how much he likes cycling now that he can’t run, mainly because of ankle problems. We also talked about some of his races and the training that he did in the past. A few days after that I ran the Round myself and Billy was at different locations on the route, with his bike, cheering for me.

Probably the first time I heard about Billy Bland was back in the early 2000s. At a race some fellow fell runners told me about races in the Lakes and Scotland which had records unbroken since the 80s. When I came to look up those races, the names of the winners were often the same; Kenny Stuart, Joss Naylor or Billy Bland. When the trail running scene was starting to develop in the rest of the world the UK scene (more often called fell running) had been around for years. With more than a hundred years of history, these races weren’t something new with a few people running mountains. Fell running was already a sport with a long history, and the competition was fierce. Many of the best times for the fell races date from the period that Billy Bland was at his peak. The fell runners were pushing each other so hard that nobody has been able to beat some of those times since then. Billy Bland was outstanding among those runners. He dominated the classic fell races, even the short ones. But what was most inspirational was the strategy he used when taking on the longer races. He started sprinting and kept the pace up for as far as possible and used exactly the same strategy even up to the 60 or so miles of rounds like the Bob Graham.

Remember that this was a different time. Life was harder. They had no fancy shoes, or gels and training plans. But they just ran harder, with Billy perhaps being the hardest of all. His races and records have been inspiring generations of runners. His fame has spread from Borrowdale and the districts around the Lakes. It has crossed the seas to inspire the sky runners and trail runners in Europe, and even to America to show how to run ultras. But his legacy isn’t in his performances, it is his generosity. He has helped many, many others to achieve their dreams, even down to pacing or advising them in their Bob Graham round attempts or fell race achievements.

In this book, Steve continues to explore the history of fell running in the brilliant style of his previous books, his in-depth analysis leading us to understand Billy Bland, whilst highlighting his achievements. Billy Bland is a legend, and he is a fine man. Steve takes us through Billy’s life, to meet and know the man behind the legend.

Kilian Jornet

Champion mountain runner

Norway 2019

PREFACE

At odd times there is a need to tell the story of how my first book on fell running came about, about a decade ago. It goes something like this.

Having always loved fell running, my respect for Joss Naylor is no surprise. He has been a real hero to me. He is in many people’s minds the greatest fell runner ever, perhaps the greatest endurance runner of all time. So, ages ago a thought crossed my mind, ‘why is it that no-one has written a book about him and his exploits’. The germ of an idea formed somewhere in the far recesses of my mind, and I suddenly decided to be the one to right this wrong. I have no idea what made me think this was achievable, or how to make it happen, but there we are. Having just begun to give the thought some working space in my brain, lo and behold a biography of Joss came out. Keith Richardson’s Joss: The Life and Times of the Legendary Lake District Fell Runner and Shepherd Joss Naylor was published in October 2009. Being in the Lakes when this news reached me, I ordered a signed copy of the book from Fred Holdsworth Books and read it with interest when it arrived. Good though the book is, it is certain that I would have told his story in a somewhat different way and dealt with some things that are glossed over in it. This made me think that maybe there WAS a book in me, and so began the search for a different subject to apply myself to.

It soon became clear that another angle on fell running was my main interest, and that I should think about that. Having long admired the exploits of Billy Bland and Gavin Bland it seemed to me that the story of these two superb fell runners, and their extended families, might prove to be a rich subject. The various members of the family have both been involved in fell running and prominent in aspects of Cumbrian life, including farming and tourism. So, the idea of The Blands of Borrowdale was germinated. With no ‘previous’ in the area, and no real idea how to progress the idea, I did some research and compiled a synopsis, with a view to pitching to some publishers. Having looked for publishers who published in what seemed to be a niche genre it was easy to compile a list with details of contacts, and also their terms for submission of manuscripts. Having no manuscript to offer yet, the first choice was what looked like an interesting option, whose website suggested: ‘An introductory email should outline the type of book being proposed and give a brief biography of the author, including their publishing history.’

At this point what was fully expected was a rejection over that first application, and then a long round of further rejections. But to my huge surprise the commissioning editor at Sandstone Press said, ‘we are interested, and my concern would be with the narrowness of the subject. I would hope to see it extended into more general fell running, its history, characters and events.’ Even then it was not an acceptance. Swallowing any pride I might have had, I thought about it and decided to re-write the synopsis to encompass this change and re-submitted it to them. The response this time was, ‘Thank you for such a thoughtful and positive response to my comments. Sandstone Press would indeed be interested in this book. Do it well and I am very confident that we will accept it.’ So, a positive response but still no deal. With hope in my heart, and still no idea if I could deliver, a start was made on researching the revised manuscript idea. This was on 13 June 2011. In December 2012 the first draft of the manuscript went off to the publisher and was reviewed anonymously by their ‘reader’. Three days before Christmas I received an acceptance email (with some suggestions from the review) and a draft contract. The rest as they say is history. The book was ‘It’s a Hill, Get Over It: Fell Running’s History and Characters’.

Having written what was nominally a history of the sport of fell running I was now inspired and over the next three years wrote a book about one particular running challenge (The Round: In Bob Graham’s Footsteps), and another about a great running rivalry (Running Hard: The Story of a Rivalry).

Now this is book four, and I have gone back to the original idea, which has been itching at me ever since. It was decided that it should focus on just one person, Billy Bland, and the backdrop to his life, with other family members as supporting characters. So, it is a biography of Billy Bland, and also includes his extended family. There is also a parallel theme of the changes in the Borrowdale valley, the part of the Lake District that Billy has lived in for over seventy years.

Taken at face value Billy Bland seems to be a straightforward man who happened to be exceptionally good at running up and down hills. But look closer and there are a series of tensions and conflicts that moulded his character and have affected his life over the years. I have explored those conflicts and hope I have presented a fair picture of this extraordinary person.

Life is a journey. This is Billy Bland’s journey.

Steve Chilton

Enfield

November 2019

GROWING UP

I don’t do any running now. Knees are all right, ankles are the problem. Used to be 5 feet 10 and went for MOT and am now 5 feet 9. Got the shrinks. No spring in them ankles anymore. If I had to run to Seatoller, a few hundred yards, then my ankles would ache. To be quite honest I am not bothered. Took fell running as far as I could take it.

I did it my way or didn’t do it at all. Be I right or be I wrong. Yes, you make mistakes, but if you have a head on your shoulders you will learn off them. There is an awful lot that gets printed that isn’t right. There is one thing about me, if I said it I will stand by it.

These two connected comments from previous discussions with Billy Bland are swimming towards the front of my consciousness on the drive up the Borrowdale valley to talk to him about his upbringing. He has already told me that writing a book about him won’t be an easy ride. This makes me more than somewhat nervous.

Clocking the bike collection in the back yard, there is a warm welcome from a still fit looking 70-something. Billy Bland certainly doesn’t look his age, although sitting opposite him it is possible to see a discrete hearing aid as we start talking about his early life. Standing at 5 feet 10 inches tall, he weighed 10st 7lbs at his racing weight. He has certainly not let himself go, is still very fit from his cycling, and is what some might consider to be underweight.

Parked out the back are their Ford Fiesta and a Citroen Berlingo van. Billy’s wife Ann joins us, often adding her perspective to the tales of early days. On this visit, and on the many other times we talked about his life, I notice Billy’s relaxed way of talking. He answers my questions patiently and without hesitating, yet he defends his point rigorously if challenged.

Billy Bland has memories of having a pretty happy upbringing in Borrowdale. The family were not well off, but he had a good deal of freedom to enjoy his surroundings. He recalls that, ‘as kids you might be asked to open a gate or run to round up a sheep if you happened to be with your father. But other than that, you were left to get on with your schooling and play with your mates.’

Billy was born at Nook Farm, which is just up the road from where he lives now. He was born in number five bedroom on 28 July 1947. His given name is William, as the church wouldn’t christen anyone with shortened names. But he was called Billy right from when he was born. He has two brothers and a sister Kathleen, who is the eldest. All four children were born at the farm rather than going to hospital. Kathleen was born in 1943, Stuart was born in 1945, and David came along in 1949.

Life wasn’t easy in the valley though. The Blands didn’t get electricity at Nook Farm until 1960. That is when the mains arrived, after a long drawn out community campaign successfully lobbied for the installation of power. Watendlath had to wait another eighteen years and was only connected with electricity in 1978.

Billy spent the first thirteen years of life without the benefit of having electricity at the flick of a switch. They had had a generator for a year or two, and even ran a television off it. Billy can remember when they didn’t have lights and they went about with a Tilley Lamp, and the cows being milked by hand.

It was very much a rural upbringing. Billy admits that he went bird nesting, adding that it, ‘is a no-no these days, which is how it should be, but that is how it was then’. He says he came home from school and got changed and away out he went, to hang out with other lads from the village. Even then there were social divides in the valley, as Billy explains. ‘It didn’t tend to happen that we’d play with Grange kids. There was a thing with Grange kids on the school bus that they were different, and it is still there yet. There aren’t many kids in Grange now. Grange always tended then to be more offcomers, and older people.’

In Billy’s early days the kids used to enjoy playing hare and hounds, a catching game. The local children also had their own swimming spot, on a corner of Stonethwaite Beck, called Mill Close. That was where everybody south of Grange would go swimming. It was where Billy learnt to swim, not that he liked it. His parents weren’t exactly happy about them swimming there without anyone being there to supervise them, but they did it anyway. When it snowed, they would go sledging on The How, ‘where the Borrowdale race finishes, that bump there. There’s about 250 yards maximum there, with a runout.’ It was a very handy location near Nook Farm.

Billy Bland and his brothers certainly got a lot of freedom granted to them by their parents, as evidenced by something he tells me about attending the Wasdale Show, way over in the next valley. ‘I’d go with my mother and father in a vehicle and Stuart, maybe David, and I would run home [over Styhead Pass] while they stayed for a drink. This was when I was at primary school mind! Which fathers and mothers would set their kids off like that now? I am sure I remembered this right, but I could do 46 minutes to Seathwaite yard from Burnthwaite which is by the church in Wasdale.’

Billy Bland was a healthy child, experiencing no particularly unusual illnesses. He did have his fair share of accidents, but no bones were broken as a kid. The Blands had two carthorses at Nook Farm, called Bonnie and Jewel. Billy remembers that he fell off one on his seventh birthday just messing about. His first broken bone was as a footballer with Keswick, breaking a small bone in his leg. He knew it was broken and came off the pitch and went to hospital and they said it wasn’t broken. He was sure it was, but it wasn’t until the following week that he was able to get it plastered.

Thinking back to childhood, Billy mentions two random fears that he can remember experiencing or being talked about. Borrowdale would not have been very diverse culturally in those days. ‘There used to be a coloured/black person come to the door to sell cleaning and polishing stuff’, Billy recalls. ‘If mother answered the door we used to get fatha to come and talk to him and send him on his way.’ The other was that Ann’s great grandmother, who used to live at Longthwaite Farm, used to have to hide in a cupboard if there was thunder and lightning, as she was so scared.

Billy can’t recall ever having pets when he was a youngster. There were four children on the farm and having a pet each wouldn’t have worked, is how he puts it. Reflecting recently on the good and bad aspects of growing up on a farm, Billy recalls that, ‘if you had asked me as a teenager there wouldn’t have been any negativity at all. It was completely different to what it is now. We used to help in the fields at hay time.’

He continues. ‘Now looking back, I can see many good parts of it, because you learnt to stand on your own two feet. There was no question you had to make your own way in life. No handouts whatsoever, which is good.’ He says he could do his football and running, although not all of the family agreed they were a good use of his time. ‘I know Uncle Noble up at Seatoller Farm didn’t approve of me. He would be saying, “no wonder he can’t do much during the day as he’s running about them fells. He would be far better helping us.” That is how they saw it. I was just wasting my time, according to some. Work was all-important, as was making a bob or two. My father was not like that. He used to say if I came home from a race, “well, why didn’t you win?” But life had been hard for that generation and it was going to be hard for us.’

Billy was brought up in an environment that was neither especially religious nor political. His parents were not religious at all. But the Bland children had to go to Sunday School. Most people did then. Ann Bland had to go too. She adds, ‘it was to get us out of the road!’ They would set off in their clogs, which were a cheap shoe option. Politics was no real concern for the family either. Billy’s parents were only interested in farming really. They might talk about subsidies for ship workers and miners, but as long as they were able to get on with the farming that was all they were interested in. Billy points out that, ‘farmers are the ones that get subsidies now.’

The mention of clogs surprised me, and resulted in a roundabout discussion of footwear, starting with the man next door to them that used to make clogs in his shed. Ann giggles, as she comments that, ‘our kids had clogs too, cute little red ones, made at Caldbeck.’ She reckoned that going back ten years or more from them everyone locally would have clogs. Billy adds that, ‘farmers like my father would get their boots made up at Rydal, by a man called Ottaway. Studded at the bottom and one short leather lace. Up at Honister quarry it was either clogs or steel toe-capped boots – strang boots they were called’.

In an historical exhibition at Grange Church, in Borrowdale, there are several panels that detail family life in the valley. One of them has some memories contributed by Billy Bland’s sister Kathleen, who was the eldest child, four years older than Billy (who was the third child). The following extract sheds light, literally, on bedtimes for the four Bland children, who Kathleen remembers all having to share one bed sometimes:

She was the tomboy with bright orange hair and exaggerated by the ‘clashy’ green twin sets her mum would knit her. And she helped look after her little brothers, recalling the tin bath where they bathed in front of the fire and helped to keep their antics in order. ‘Going upstairs to bed,’ she says, ‘I’d carry the candle so carefully.’ Yet the flickering flame might blow out in the draughty old farmhouse. ‘Mother would scold me for dripping candle fat on the carpet.’

Hot water from the kitchen range filled the tin bath. Cold water from a bucket cooled it off and green Fairy soap worked up a lather. That kitchen range was kept black-leaded, prepared by using a kind of liquid shoe polish – and elbow grease. The paraffin lamp had to be watched too. If the wick went untrimmed, the flame rose and blackened the ceiling with soot.

Kathleen also recalls two aspects of the cleanliness that the family typically sought:

She remembers laboriously scrubbing the farmhouse flagstones on her hands and knees – with a drop of milk in the water ‘to bring out the blue’ of the slate. Because there was no television to watch in the evenings, the family would sit round and make ‘proddy’ mats to cover the flagstones, using pegs from bones. Using these, you pushed pieces of old clothes and rags cut up into strips through a hessian base that was stretched on a frame.

When it was time for him to go to school Billy had about a kilometre to go to get to Borrowdale School. At the time that he started school it was next to the church in Stonethwaite. Both Billy and Ann Bland went to the primary school there, with Billy being two years ahead of Ann, and both took the eleven-plus exam. The school has been replaced by six houses, with a new school being built just along the road in 1968. This new school was built by the grandsons of the builder of the old school, all from the Hodgson family, a long-established firm from Keswick.

Between 20 and 45 pupils attended Borrowdale School for the years Billy was there. He freely admits he was not a good scholar and didn’t want to be there, but he had to be there by law, ‘so that was that’, he says. He recalls that he once hid in the coalhouse so he could nip away and watch the sheep dipping. He got caught and was given a hiding. ‘My fatha was a lovely gentle man who wasn’t bothered, but I got plenty from my mother. She lost it quite easily with all of us lads. We were young buggers who thought we knew it all.’

After primary school children from the valley went onwards to Keswick Grammar School or Lairthwaite Secondary Modern (also in Keswick), depending on their eleven-plus results. These two schools are now combined as a comprehensive school (Keswick School). There was a special school bus to take pupils to Keswick from Borrowdale. Ann lived half a mile up the road from Billy, so they got to know each other well early in life, meeting every day virtually, going to school together for instance. But things weren’t that simple. Ann was at Keswick Grammar, and says that pupils at Lairthwaite School, where Billy was, had ‘no regard’ for those at the Grammar. Ann notes that pupils from the Grammar School used to sit at the front of the bus and pupils from Billy’s school sat at the back, by tradition.

Billy reckons that they didn’t get out of the valley much. ‘We had a Morecambe trip every year that my mother was one of the organisers of. We went on two buses and that was our almost yearly trip. My uncle Nat would also take us in the Land Rover to Allonby [on the NW Cumbrian coast] for a day out but that was it. But we were happy enough.’

At Lairthwaite School Billy Bland met Howard Pattinson. He is 72 years old, 6 months older than Billy, and they were in the same class at the school. Howard Pattinson was born in Keswick and lived there from 1946 till he was 23 years old, when he left to move down to Hertfordshire. In Keswick he worked at the Keswick Reminder newspaper and went to college in Carlisle and realised there was more to print and design than he was ever going to get in Keswick. He says that one strong catalyst for change for him was that being in the town centre going to work indoors when everybody else is on holiday in Keswick isn’t a good thing. ‘I thought if I can get a job in a college and get the holidays then I would have more time in Keswick to explore the fells than when I was living there.’ He says he ended up working at a great college, West Herts College (in Watford), and then stayed there for 38 years. Ironically his own fell running started after he moved south.

Howard Pattinson and I recently had a long chat after I drove round the M25 to meet him in Rickmansworth, at his partner’s house. He has a good memory of his early life in the Lakes, where he still has a house.

He first went through some school experiences that he and Billy shared. ‘I have a picture of a football team at school and Billy is in there and so am I, I think he was only a reserve. He was quite small. Billy and I were just like any other kids at school. We didn’t necessarily have great natural talent for running or football, but we worked at it.’

Pattinson didn’t really know Billy before Lairthwaite Secondary School, as they lived at opposite ends of the Borrowdale valley from each other. But he has an interesting perspective on their two differing upbringings. ‘I envied him living in a house in Borrowdale. He was in a farm and I was in a council house in Keswick. As a child I visited his house [Nook Farm] a couple of times I suppose, nothing more than that. It seemed heavenly, beautiful. I would have liked to have been a farmer if I could.’

Pattinson recalls that everyone ran a little when they were at school. ‘I got some fitness from doing a milk round. I am not sure what Billy would have been doing at the time. I didn’t knock about with Billy really, because he went back up Borrowdale after school.’

It was practical things and sport that Billy liked when he was younger. He liked woodwork as it was working with his hands. He notes wryly that he got the woodwork prize at school. ‘I have never had any issues in my head about myself from school. I have always had a mind that thought for itself and if someone didn’t agree then they were wrong!’, he says disarmingly.

There had been no school trips at their primary school, but from secondary school Billy remembers going to the steelworks at Workington, and also to the coalmine at Haig Pit, under the sea at Whitehaven. ‘That was interesting, and there has been some talk of opening it up again. School was more practical-based in my time, but now it is all university-based. You were not looked on as a failure then if you wanted to take an apprenticeship in something.’

Howard Pattinson is very scathing about the school system at the time, as he had experienced it. ‘I was at Crosthwaite [Primary] School, my dad had died, and my mother was disabled and had no money. I was second in everything at school, but the headteacher (Mr Slee) said, “you are not going to go to Keswick School because they will ask for money your mother can’t afford. You are going to Lairthwaite regardless of your eleven-plus results”. They were a lot of us like that. I never did any GCSEs, none of us did. I left school with no qualifications whatsoever. The wasted potential in our era was criminal.’

The teachers couldn’t have cared less, Pattinson reckons. ‘If someone asks you, do you want to work in the garden or sit in a maths lesson, you’ll go in the garden won’t you? One or two teachers were half interested, but most were not. Two of us left at Christmas and there were two jobs available. Dennis Cartwright got first choice and he went to the Gasworks, and I was left with the printers. However, I finished up as a Senior Lecturer and Course Director of a BA (Hons) Degree in Graphic Design.’

He concludes, ‘at school we were never introduced to the countryside or anything. But it was just beginning to be considered. There was a man called Clarke came there who was keen on the outdoors, and he started to take groups walking, but that must have been after Billy and I had left. Basically, we both went through school then left and got whatever jobs we could. It was shocking really.’

Billy Bland does remember collecting wildflowers as a kid and pressing them in a book. It speaks volumes about Billy that he even made this competitive. ‘It is a no-no now to pick wildflowers, but that was how it was then. You put the name beside them, and it was a competition to see who could collect the most.’ Everyone did it, and it helped them learn their names and also to be able to recognise the flora. It was the start of Billy’s enduring love, and understanding, of the countryside. Billy Bland’s record of the wildflower species he’d identified during his school days is now famous locally – it was highlighted in the September 2017 issue of Borrowdale News.

At school, as a farmer’s son you just thought that by instincts you could soon be a farmer, but Billy never really got the opportunity. His older brother Stuart was already there before him to take on the family farm and so Billy had to get a job. When Stuart left the farm, David was just leaving school, so he went on to the farm, with Billy getting bypassed in a way, which he says he wasn’t that bothered about. ‘It was just something that happened, you didn’t kick up a fuss about it.’

Recently Billy has been a very keen cyclist, but there were no new bikes for Christmas in his household when he was young. ‘We had bikes on the farm but who knows where they came from. There were certainly no brand-new bikes that I can remember. We used to double up, using the crossbar a lot too as kids.’ The first year of his working life he cycled to work, and then he got a motorbike. It was second-hand bike, described by Billy as ‘a rubbish bike.’ He went on to get a bigger and better one, a Velocette.

In the bad winter of 1963 Derwentwater got iced over and they rode their bikes on it to take a short cut home. ‘There was a lad from Keswick used to come across the ice on his bike. It was that thick someone drove a bus on it once.’ Ann recalls that she was at school and they couldn’t have games lessons, so they used to go and skate on the lake.

Both Ann and Billy point out that you just knew everybody locally when they were young. Billy’s youngest brother David is the same age as Ann and was in the same class as her in Borrowdale school. There were only six pupils that took the eleven-plus exam that year, and three went to Keswick School and three to Lairthwaite School. Both David and Stuart Bland also went to Lairthwaite School, like Billy. The little Bland boys all had to go to school with the same things on when at primary school. Their mother used to knit them the same tank tops. She was an expert at knitting, and all the grandchildren had beautiful knitted cardigans and jumpers.

Billy and Ann began courting as teenagers. Ann recalls that she was still at Keswick School, so says she was just sixteen. ‘We had to go to school on Saturday mornings. I took my O Levels and the night before the English Literature exam Billy took me dancing.’ She adds that her school results were nothing to be proud of. On leaving school she worked as an audit clerk in an accountant’s office in Keswick for five years.

On being asked how much of a romancer Billy had been, Ann immediately came back with, ‘he must have had something!’ Billy sagely responds, ‘what you see is what you get. I don’t think I have changed in any way.’ He goes on to explain that there was a cinema in Keswick and a dancehall there too. ‘It was opposite Fitz Park, where the Youth Hostel is now, by the bridge. You went downstairs into the dancehall. The Kinks played there once, when they were on their way up in the world.’ They also used to go out with Billy’s brother Stuart and the girl who became his wife, and another couple. They used to go to the Coledale Inn, in Braithwaite, to have a drink or two, although Ann wasn’t old enough to drink yet. They then went on to the Pavilion for a dance.

Ann and Billy were married at the ages of 20 and 22 respectively. But their parents didn’t know it was happening, as they just took off and did it. They were married at Cockermouth Registry Office on 21 February 1970 in what Ann describes as a ‘seven-minute wonder’, as people in the valley saw it. After the event, Billy played football in the afternoon. ‘Our parents just accepted it, even though we had nowhere to live. So, we lived with Ann’s mum and dad’, says Billy now.

Ann tops it with the coup de grace. ‘In a small valley like this everyone is thinking, “well she must be pregnant then”. [Laughs] Well, she was.’

Billy Bland had an interesting route from Nook Farm to Mountain View (where he now lives). After he married Ann in 1970, they both lived with Ann’s parents for three years, from 1970 to 1973. This was half a mile down the road at a hamlet called Peat Howe, in the end cottage. When he retired from farming in 1964 Ann’s grandfather had wanted to live next door to Ann’s parents. Dick Richardson, who was in that next-door cottage already had two children and it was too small for the family. In the meantime, Ann’s grandfather had bought a house at Mountain View for £1,800 (in 1964). It was intended for Dick really, so he could move there and leave the Peat Howe one for the grandfather. For a while then, Dick Richardson lived at Mountain View and worked up at Honister. But then he put in for a farm because he had a farming background, and he secured Watendlath Farm through the National Trust.

While they lived with Ann’s parents in that tiny two-bedroom end cottage Billy and Ann had two children, Andrea (born 1970) and Shaun (1972). Then they moved to the Mountain View in 1973, as it had become available after Dick Richardson’s move. When they had lived in the house for just one month, suddenly Ann’s father died at the age of 55. Ann’s mother was in an awful state, so they moved back in with her for a while. Twelve days later Ann’s grandfather died. Ann’s mother had lost her husband and her father within a fortnight. Ann’s grandmother lived on in the house and died about 3 years later. Ann’s mother died four years ago.

Ann confirms that they got on well with her parents when they lived with them, and subsequently too. Billy’s take is that both pairs of parents knew what they were dealing with, with Ann and himself. ‘We are what we are. Don’t pretend to be something you are not. I have never believed in that and I never will.’ Ann added, ‘I don’t think we ever had a wrong word with my parents. His mother I could fall out with though.’ Billy added with some feeling in his voice that, ‘really my parents should have supported us more than they did. It is what it is, you can’t change it.’

Childhood and upbringing can shed light on a person’s future life, but we must also look at how their family background has influenced that development process. To do this we will step back through a couple of generations of the Blands.

MY HOMETOWN

Borrowdale has the character of a cul-de-sac valley, even though the road over Honister Pass can take you across into Buttermere. It famously includes the narrow section near Castle Crag that Alfred Wainwright described in his guidebook thus: ‘No high mountain, no lake, no famous crag, no tarn. But in the author’s humble submission, it encloses the loveliest square mile in Lakeland – the Jaws of Borrowdale.’

There was a time when you couldn’t move around in the top end of Borrowdale without tripping over someone from the extended Bland clan. Over the years members of the family have owned or been tenants at many of the farms in Seatoller, Stonethwaite and Rosthwaite. Billy Bland’s family background is fundamental to his development as an individual.

Billy Bland’s grandfather Willie was not from Borrowdale but from over the fells. Willie Bland had been born in Patterdale in 1883, to James and Esther Bland, a farming family. The family moved when he was seven to Brotherilkeld Farm, Eskdale. James Bland then moved the family to Scar Green (Calder Bridge) at the turn of the century. By now Willie was a teenager with seven brothers and sisters. Around 1910 Willie married Elizabeth and had had his first three children when they all moved to a hamlet called Nannycatch (near Cleator Moor).

Here Willie was a tenant farmer with lands between Dent and the Cold Fell Road. Willie Bland eventually had a family of six boys and one girl, who all had to walk to school two or three miles away in Ennerdale Bridge. He then took the step of moving into Borrowdale to take on a tenancy at Nook Farm in Rosthwaite in the 1920s with all the children: Jim, Jack, Billy, Joe, Nathan and Noble, and their sister Esther. Nook Farm was eventually one of many farms that the National Trust bought up, a trend spear-headed by one Mrs Heelis (Beatrix Potter as was), before she died in 1943.

The details of the National Trust purchase of Nook Farm, made on 3 Apr 1947, are shown on their website archive as:

Nook Farm, Rosthwaite – 58.97 hectares (145.72 acres) Land comprised of fields and farmland. Purchased in 1947 from Lt Col. E. S. Jones, in memory of Capt. John Diver, of the Royal Army Medical Corps. Farm buildings (and 2.40 hectares of land (inclusive)) were also bought with a bequest from Mrs S. J. Tomlinson.

When Willie Bland retired from Nook Farm he moved to Cleator Moor, close to where he had previously lived (at Nannycatch), and Billy’s father Joe took over the farm tenancy in Rosthwaite. Farmers often find it hard to stop living the farming life, so Willie used to look after some of Joe’s hoggs (sheep up to their second shearing) when they were sent over to him to winter, as they do better away from the fells. They would take the sheep to Cleator Moor in October, having been born in the Spring. The grandfather would look after them, going the rounds to see they weren’t stuck in briar and that the fences were OK. When it came to bringing them home at the end of March, they walked them from Cleator Moor to Buttermere (over the pass by Floutern Tarn, north of Great Borne) and they over-nighted there. Billy’s father’s mate was at Wilkinsyke Farm (at Buttermere) where they would be penned overnight. They would go back the next day and walk them over Honister Pass. ‘Too tight to pay for transporting them, I would say’, says Billy now. ‘They would be one of the last one’s that drove their hoggs, rather than transporting them.’ Before grandfather Willie went to Cleator Moor they used to winter the hoggs at Isel, between Bassenthwaite and Cockermouth, as well as at Cleator Moor. A family called Nicholson used to mind them.

Billy’s father Joe and his uncle Nathan (or Nat), who was a single man who never married, ran Nook Farm between them. They were involved in sheep farming predominantly. In those days all farms in the valley had a cow and their own potato fields. You collected the bedding for your calves, by cutting bracken.

Billy’s mother’s Lily (nee Stuart) was brought up by her Auntie Hannah, and they lived at several different locations in Borrowdale. The trail is a little too vague to identify the exact locations involved. Lily did live at Cragg Cottage in Rosthwaite for a while just before she married, which is just across from Nook Farm, and that is how she met Billy’s father Joe. Lily and Joe were married in 1942, on 20 February, at Borrowdale Church.

Joe Bland was a farmer for all his working life, not always on his own farm though. He worked at Gatesgarth Farm before his own father retired, while waiting to take over Nook Farm. Joe’s brothers were all farmers, who all spread their wings to take on a range of positions in the area. Nat shared the running of Nook Farm with Joe, Jim was up at Watendlath (via a spell at Stonethwaite), Noble was at Seatoller Farm, Billy (Billy Bland’s uncle Billy) at Croft Farm in Stonethwaite (which isn’t a farm anymore). Finally, Jack worked for Billy’s wife Ann Bland’s grandfather at Longthwaite, but never had a farm of his own. This was the first of several connections between the Billy Bland and the Ann Bland family branches. None of the Bland brothers owned their own farm until Jim went on to Ravenstonedale.

Fell runner Dave Hall both trained and worked with Billy Bland at times. He has memories of camping in the early days up at Seatoller Farm on a basic campsite there. He says, ‘I think Billy’s uncle used to own it. He used to come round and accurately predict what time it would start raining. If he was wrong, he would say his watch was wrong.’ Billy confirms that it would be his uncle Noble, adding, ‘he would say that, he was a bloody old blowfat, as I would describe him’. A classic Bland expression, apparently meaning, ‘think you know everything’.

Lily Bland was no more or less than a farmer’s wife. Women at that time rarely went out to work. She had to work when living with Auntie Hannah though, who was very hard on her as a young girl. They were very poor, and Lily was made to go out and do various cleaning jobs. She didn’t have a very good upbringing, as she was born out of wedlock. It was many years later that Lily found out that Hannah wasn’t actually her mother.

When Joe and Lily Bland were there, Nook Farm and Yew Tree Farm (which are next door to each other) encompassed most of the fields in that part of Borrowdale. Nearly all the intakes to the south of Castle Crag went with Nook Farm, including Castle Intake and Lingy Bank. Being called ‘Lingy’ suggests a prevalence of heather, but when Billy was young it was full of stumps of trees which had been felled in the First World War, and they had scythed the bracken down for years and years to keep it good and grassy. But it had all been wooded at one time. At this time a tenancy would have a patch of land right where the farm was. Farms now are all more spread about because they have bought grounds further afield, for better grazing or growing.

There are many Edmondsons in the history of Borrowdale, and Ann Bland’s grandmother was an Edmondson before she married. But for a while the Blands were pretty dominant, what with all the brothers working the various farms. ‘There wasn’t much room for anybody else!’, recalls Billy. In writing about Thorneythwaite Farm, Ian Hall commented that, ‘if all the [Bland] children had been the same age they would have filled Borrowdale School unaided.’

Contemporary photos show a typical farm scene – workers down on their knees tending the turnip crop, real backbreaking work. Billy points out that, ‘in those days farmers wore a shirt with no collar, and never EVER took that shirt off when working in the fields. They had really brown arms though.’ Joe and Nat used to clip the sheep by hand at Nook Farm.

Ann Bland’s family are also from Borrowdale. Her maiden name is Horsley, and her given names are Margaret Ann. Her father, Maurice Horsley, was from Braithwaite, and ended up working at forestry for Lord Rochdale on the Lingholm Estate, near Keswick. This was after Billy had left his job there, as her father did not go there till he was fifty years old. Earlier he worked for a timber merchant at Greenodd, over near Ulverston, and he travelled there every day in an old van. Then they made him redundant, and he went to Lingholm after that. Ann’s mother, Peggy, was brought up down at Longthwaite Farm.

Big families were the norm then, and Ann’s father had seven sisters. Ann’s mother was bridesmaid when Billy Bland’s mother and father got married, and her mother was also his sister Kathleen’s godmother. Billy and Ann knew each other at primary school, although they were separated by two school years because of the age difference.

Billy’s mother Lily used to take in visitors for bed and breakfast in the summer and all the children then used to have to sleep outside in a wooden hut, as their bedrooms had been let out. You could hear the rain pattering on the roof, but the money helped to keep the family afloat. This happened from when Billy was quite little until he was about sixteen. Times were harder than they are now. There were no other farm workers, but as oldest son Stuart Bland had to start working on the farm as soon as he left school.