5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

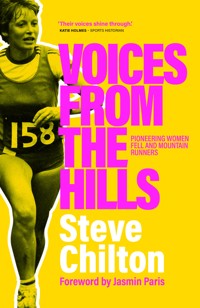

'A must read for anyone with a passion for women's equality and sport.' -Sue Anstiss Voices from the Hills is the story of the barriers encountered by the first female fell runners who fought to participate in the early days of this male-dominated sport. Despite experiencing discouragement and resistance, these women responded with personal courage and self-confidence. Thanks to them, women now compete at traditional fell races, international mountain races and endurance challenges such as the Bob Graham Round in increasing numbers. Told predominantly through interviews with pioneering female athletes who recount their lives and running careers, this is the story of a fight for equality of opportunity and reward.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2023 by

Sandstone Press LtdPO Box 41Muir of OrdIV6 7YXScotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Steve Chilton 2023

Editor: Robert Davidson

The moral right of Steve Chilton to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-914518-19-5

ISBNe: 978-1-914518-20-1

Cover design by Ryder Design

Ebook compilation by Iolaire, Newtonmore

To every female athlete I havecoached who has enriched my life

People who end up as ‘first’ don’t actually set out to be first. They set out to do something they love.

CONDOLEEZA RICE former USA Secretary of State, on changing acceptance of women in sport

We should always remember the ones who went before, as they made a path for us.

SARINA WIEGMAN manager of the England Women’s football team on winning the Women’s EURO Championship 2022

Contents

List of photographic plates and credits

Foreword by Jasmin Paris

Prologue

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 You can’t do that

Female Frailty: Fiction or Fact? Pedestrianism, The Olympics, and Marathons.

CHAPTER 2 Beginnings

Opportunites and Competition Open Up: The 1950s and After.Profiles: Carol McNeill, Joan Glass

CHAPTER 3 Competing unofficially

Governing Bodies Rule. FRA and Race Organisers Awaken. The Sex Discrimination Act. Profiles: Carol Walkington, Bridget Hogge, Anne-Marie Grindley

CHAPTER 4 First official women’s races

Breaking Rules to Achieve Change and Recognition.Profiles: Pauline Stuart, Joan Lancaster, Ros Coats

CHAPTER 5 An expanding race programme

Women Speak Up. Major Races Open Up and Others Have to Follow. The Cumberland Fell Runners Association. Profiles: Jean Lochhead, Sue Parkin, Norma Hughes

CHAPTER 6 A women’s fell running championship

Taking on Committee Posts in the Sport. The First Women’s Championships. Still Some Unofficial Entries. Profile: Véronique Marot

CHAPTER 7 Big rounds

The First Bob Graham Rounds and then 58 Peaks in 24 Hours. Profiles: Jean Dawes, Wendy Dodds

CHAPTER 8 Consolidation

The 1980s: Race Fields Increase. More Events Open Up. Contrived Short Courses in Terminal Decline. Profile: Fiona Wild

CHAPTER 9 Running abroad

International Fell/Mountain Running. Sierre-Zinal. Snowdon International Race. A World Cup. Profile: Brenda Robinson

CHAPTER 10 Record breaking

Records Fall, Great Racers and Champions Emerge: Carol Haigh and Pauline Haworth. Profiles: Vanessa Brindle, Christine Menhennet.

CHAPTER 11 Further abroad

World Mountain Running Trophy Comes to Keswick then Edinburgh. European Mountain Running Championships held in Wales. Profiles: Carol Haigh, Sarah Rowell

CHAPTER 12 More record breaking

1989: A Year of Many Course Records. Profiles: Angela Carson, Ruth Pickvance

CHAPTER 13 Home and away

The 1990s: More Races Abroad. Race Start Issues. First Dragon’s Back Race Across Wales. Profiles: Tricia Calder, Jackie Hargreaves, Alison Wright, Elaine Wright

CHAPTER 14 More challenges

More Big Rounds: Paddy Buckley, Charlie Ramsay, and a Bob Graham. Let’s Do All Three. Profile: Helene Diamantides

CHAPTER 15 Going further

Even More Rounds: Joss Naylor Lakeland Challenge, Lake District 24 Hour Fell Record. Profile: Anne Stentiford

CHAPTER 16 To the millennium

The Late 1990s: More Stunning Records and Rise of the Veterans. Profiles: Nicola Davies, Menna Angharad, Angela Mudge

CHAPTER 17 Relays

Mostly Relays: Pennine Way, Coast To Coast, Calderdale Way. The Hodgson and the FRA. Profiles: Linda Lord, Eileen Jones

CHAPTER 18 Professional versus amateur

Encounters with the Professional Scene. A Barrier Breaker. Profile: Kirstin Bailey

CHAPTER 19 Women coming first

Wonderful Winning Women – Outright: Sarah Rowell, Helene Diamantides, Carol Haigh

Acknowledgements

List of photographic plates

1 – Kathleen Connochie training for the Ben Nevis race with Duncan MacIntyre, 1955

2 – Kathrine Switzer being hassled by the organisers of the Boston marathon, 1967

3 – On the start line of the Muncaster fell race, 1977. L-R: Jean Dawes, Maraline Baines, Audrey Orr, Peggy Walker, Gillian Naylor, Joan Glass, Joan Lancaster, Carol Walkington, Anne Bland, and Anne Todd

4 – L-R: Joan Glass, Anne Bland, Carol Walkington, Joan Lancaster, Peggy Walker, Jean Dawes at the Crag Fell race, 1977

5 – Joan Glass at Muncaster, with Bob Roberts, mid-1970s

6 – Ros Coats, Pendleton Hill, 1978

7 – Jean Dawes finishing her Bob Graham Round, 1977

8 – Anne-Marie Grindley at Muncaster, date not known

9 – Jean Lochhead at Pendle, 1978

10 – Carol Walkington at the Crag Fell race, 1978

11 – Anne and Pete Bland, KIMM, 1974

12 – L-R: Jean Lochhead, Brenda Robinson, Gillian Pile, Linda Lord, Anne-Marie Grindley, at Pendle, 1979

13 – Brenda Robinson at the Three Peaks race, 1979

14 – Carol McNeill with Wendy Dodds at the KIMM at Arran, 1980

15 – Vanessa Brindle at Fiendsdale, date not known

16 – Competing with Jean Dawes and Carol McNeill in the Three Peaks yacht race, 1980, Anne-Marie Grindley helps to row their trimaran through the Corran narrows.

17 – L-R: Cath Whalley, Fiona Wild, Pauline Haworth, Carol McNeill, Ros Coats, Marguerite Pennel, and Joan Lancaster at the Wasdale race, 1981

18 – Fiona Wild at Ben Nevis, 1981

19 – Pauline Haworth on the way to winning the Ben Nevis race, 1984

20 – Angela Brand-Barker with the British Fell Championships Trophy, 1983

21 – Bridget Hogge at Moel Eilio, 1984

22 – Véronique Marot at the Sierre-Zinal race, 1984

23 – L-R: Eileen Jones (Burnip), Eileen Woodhead, Katy Thompson, Karin Goss (Taylor), Maureen Ashton. Front: Linda Bostock, at the Shepherd’s Skyline race, 1988

24 – Carol Haigh at the World Cup race, Keswick, 1986

25 – Helene Diamantides on the Everest base camp run, with Alison Wright, 1987

26 – Sue Parkin at Coniston, 1990

27 – Trish Calder at the Edale Skyline, 1990

28 – Ruth Pickvance at the Chew Valley Skyline, 1990

29 – Kirstin Bailey at the Sedbergh Gala race, 1987

30 – Anne Stentiford on her 24 hour Lake District Peaks Record round, with Colin Ardron, 1991

31 – Elaine Wright at the Sierre-Zinal open race, 1991

32 – Jackie Hargreaves, venue and date unknown

33 – Sarah Rowell at the Three Peaks, 1994/96

34 – Angela Mudge winning at Sierre-Zinal, 2001

35 – Nicola Davies at the Ingleborough (Inter-Counties) race, 2003

36 – Angela Brand-Barker handing the Olympic relay torch to Joss Naylor, 2012

37 – Christine Menhennet at the Ring of Steall race, 2016

38 – Wendy Dodds at the Three Peaks race, 2021

Photo credits

Plate 1 – Duncan McPherson

Plate 2 – Boston Herald

Plates 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 11, 17 – Tommy Orr

Plate 5 – Joan Glass

Plate 7 – Jean Dawes

Plate 9 – Jean Lochhead

Plates 12, 15, 19, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 35 – Dave Woodhead

Plate 13 – Brenda Robinson

Plate 14 – Carol McNeill

Plate 16 – Anne-Marie Grindley

Plate 18 – Fiona Wild

Plate 20 – Angela Brand-Barker

Plate 22 – Véronique Marot

Plate 25 – Helene Diamantides

Plate 29 – Kirstin Bailey

Plate 30 – Anne Stentiford

Plate 31 – Elaine Wright

Plate 32 – Dave Hughes

Plate 33 – Sarah Rowell

Plate 34 – copyright not known

Plate 36 – Angela Brand-Barker

Plate 37 – Christine Menhennet

Plate 38 – Wendy Dodds

Foreword

I started fell running as an adult in 2008 and was struck immediately by the warmth and inclusivity of the fell running community. In a midsummer evening race close to home in the Peak District, I experienced for the first time the camaraderie of that shared effort as I followed the line of runners to the summit trig point, and then the adrenaline rush of the fast, scarcely controlled descent across heather and mud to cake and tea at the finish.

That day was the start of a new passion, which has brought me intense joy, great satisfaction and, I believe, a better understanding of who I am and what I’m capable of. I love the humbleness and lack of elitism that fell running entails, and the way in which enjoyment of the hills brings people together, regardless of their differences. When I won the Montane Spine race outright in 2019, setting a course record in the process, the running community was overwhelming in its support. Given the history of female endurance hill runners like Helene Diamantides, they were also probably not as surprised as the media seemed to be.

It seems scarcely believable therefore that, less than fifty years ago, women were not allowed to compete in fell races at all. Facing longstanding tradition and gender expectations, it took a string of passionate and committed women, pursuing the pleasure of running in the mountains, to change the pervading attitude amongst the running community and the public in general.

In this book, Steve Chilton has turned his attention to exploring the stories of those female pioneers, their motivations, experiences, and challenges. Building on his previous books about the history of fell running, Steve combines meticulous research with personal interviews to shine a light on those that paved the way for the gender equality we enjoy today, from the record breaking champions to those who played a quieter but equally important role behind the scenes.

On a personal level I’ve often referred to my own fell running female heroes, including Angela Mudge, Helene Diamantides and Wendy Dodds, all of whom are covered here. Yet I realise how little I knew about so many others; those who raced before they were allowed to, sending in entries with first name initials only and registering with coat hoods pulled up to disguise their female identity; and those who took part in the face of blatant criticism, such as Véronique Marot when she raced around Ennerdale for the first time, resplendent in long sleeved gloves.

My own experiences of gender discrimination in running have been negligible, typically relating to prize giving rather than the sport itself. In 2014, when I finished third overall and first lady in the Wasdale Fell race, narrowly beaten to second place in a sprint finish off Lingmell, I was surprised at the prize giving when the first two men both received a trophy (one being for a veteran over 40), but one didn’t exist at all for the ladies. I joked about needing to run faster next year to finish in the top two, nevertheless I was pleased to see a female trophy appear for the next edition of the race.

I’m immensely grateful to the women who paved the way for my generation to compete in fell races as equals with our male counterparts, free to run the same courses neck and neck, sharing the highs and lows, and ultimately the joy that time spent in the mountains brings. Throughout this book, many of those ladies point out that at the time they were simply enjoying running in the hills and didn’t consider themselves to be pioneers. Yet it needed that group of fearless women, ready to pursue what they loved to do, and to defy expectations and constraints of society, to open the floodgates for the involvement of women in fell racing, to normalise their presence and to push increasingly for equality in terms of opportunity as well as achievement on the hills. Thanks to this book those trailblazing women will be recognised for the contribution they made, and continue to make, for the fell running dreams of women today and in the future.

I believe that the progressive participation of women in fell running shows what can be achieved when passion and self-belief work as a force for good, and I hope the same can now be achieved in terms of ethnic diversity in our sport for the future. I believe wider enjoyment of the hills and mountains will foster further understanding and desire to protect them, essential for not only our generation but for those to come.

jasmin paris

Edinburgh

Scotland, 2022

Prologue

In researching this book, I spoke to many people involved in the early days portrayed within. I have tried to reconstruct the story of this era (the second half of the twentieth century), and the issues and actions involved, with a fairly arbitrary cut-off of the turn of the millennium. The basis of the story is the barriers and struggles encountered and the personal courage and self-confidence shown by athletes doing things because they wanted to. What I hope makes for interesting reading is that it is predominantly told through the words of those early pioneer women, many of whom have said how much they enjoyed looking back over their running careers, some of which are still ongoing.

The many interviews with athletes that provided the basis for the book took place throughout 2021, mostly when we were in various stages of lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This meant that in-person interviewing was out of the question. When offered a choice between telephone or email conversations approximately half chose each option. Both options allowed me to explore each athlete’s background and their place in the evolving story.

In one conversation Ruth Pickvance said, ‘I think it’s so great that you’re doing this [book].’ She then dropped a bomb by saying, ‘A few years ago I said to Helene Diamantides/Whitaker, “Shall we write a book about women’s fell running?” We both thought it was a good idea, but life’s pressures took us in other directions!’ Ruth later added an unprompted remark that could have been a precis of the subject. ‘It is not just about women going running. It is about, why was it like that at the time, and what else was going on? How did the people involved feel about it? I feel very differently now looking back at it than I probably did at the time.’ I had exactly that in mind when I started researching the manuscript, and hope that by speaking to a good number of the pioneers I have managed to give a real feel for what it WAS like through the eyes, and memories, of some of the participants. Ruth, and Helene, may of course have written a very different book, but for now this is a history of early female fell runners.

[Note: in most cases I have used athlete’s surnames as they were at the time of competition (i.e. how it would have appeared in results), with a note of name changes where relevant.]

Introduction

Dawn. A bitter, damp Welsh mountain morning. The special train lay hissing and clanking, awaiting its one lady passenger. Reaching the end of the line by 8am, Esme Kirby could finally set off on her epic challenge to climb fourteen mountain summits faster than any woman had done before, and achieve lasting fame. Having caught the specially arranged train up to the summit of the first mountain, she had a quick drink of coffee and set off at a trot just before eight o’clock in the morning. It was damp and mightily cold. Esme had trained hard for this, but nagging away at the back of her mind was the slightly strained ligament she had experienced a few days ago. She and her pacer, her friend Thomas, set off into the mist.

The clag had set in for the day, meaning that finding the fourteen summits was often difficult. Esme eventually limped up to the shelter on the last summit. She had taken nine hours and twenty-nine minutes. It was exactly one hour faster than the previous record, which had been set by a man. Having finished the challenge, there was still five miles to go to get back to their car.

This was back in 1938, and Esme had just traversed the Welsh Three Thousands in a new record time (although her husband and two friends had only taken 8 hours 25 minutes, having set off an hour after her). Esme’s name is not one that comes to mind readily when recalling pioneer female runners, but she was certainly ahead of her time. Her husband at the time was Thomas Firbank, author of the best-selling book ‘I Bought a Mountain’. Both of their exploits garnered huge publicity and certainly raised a few eyebrows in the mountaineering establishment, such that Firbank’s two companions felt it necessary to write an apology letter in the Climber’s Club Journal – about turning the mountains into a competitive arena. Thomas Firbank did not like the fuss that was being made, but Esme seemed to enjoy it immensely, particularly being invited to London by the BBC and being featured in several of the national newspapers.

Esme Kirby’s single-minded approach certainly showed the way for later females to challenge themselves in similar ways. She went on to become a leading conservationist and founded, with her second husband Peter Kirby, the Snowdonia [National Park] Society in 1958, to try to ensure the mountains were protected from inappropriate development.

CHAPTER 1

You can’t do that

Female Frailty: Fiction or Fact? Pedestrianism, The Olympics and Marathons.

‘Allowing women in sports would harm their feminine charm and degrade the sport in which they participated.’

This attitude, as espoused by Baron de Coubertin (founder of the International Olympic Committee) solidified one of the greatest barriers to women’s participation in sport.

When writing a history of any topic it is often not easy to know where to start (or indeed stop). Are the instances of pioneering women in other branches of the sport of running directly relevant to a history of women in fell and mountain running? What they DO show is that women have faced incredible obstacles to their participation in endurance sports, both on grounds of their (perceived) frailty as a gender, and of the perception of their role within society.

The myth of female frailty was an unproven medical belief that strenuous sport would damage a woman’s body and make her infertile. Girls were told that they would become masculine and sterile if they took part in vigorous sporting activity. It was suggested that their uteruses might fall out, and it was even seriously considered, by some with extreme views, that women were born with a finite amount of energy and if they used it up on active sports, they would not have energy to give birth. Furthermore, Patricia Vertinsky noted1 that the thinking in the medical profession in Victorian times was that ‘in addition to the monthly menstrual drain of energy, at each birth a portion of a woman’s vital energy was transformed and imparted to the new-born child. As each child was born, the mother experienced a physical loss to her over-drained body’.

Women had been forbidden from participating in the Ancient Olympics, way back before the Modern Olympics. A woman who was caught even as a spectator at those Games could face execution. Women in ancient Greece held their own festival to honour the goddess Hera every four or five years – the Heraean Games. There is hardly any historical record of these games, which probably started around 776 BC. About the only source of information is a set of writings from the Greek geographer Pausanias. Only women could compete in the Heraean Games, and Pausanias suggests they had to be virgins. As opposed to competing in the nude, like competitors in the male-only Panhellenic Games, the women wore knee-length tunics that left the right shoulder and breast exposed. The event took place in a stadium, with several running events, possibly ranging from 177 metres to about 3 miles.

It is worth looking at several instances in later times, where pioneering women went against the grain, and the expectations of them, in the era before it was normal for them to be involved in endurance events alongside men. In all cases the participants showed great strength of character.

Pedestrianism was a nineteenth-century form of competitive walking, often professional and funded by betting, from which the modern sport of racewalking developed. It also produced some of the earliest formal endurance records. The exploits of nineteenth-century (male) ‘pedestrians’ such as Robert Barclay Allardice, and the gloriously named duo of Corky Gentleman and the Flying Pieman, provide some of the highlights of this stage of the development of men’s endurance sport.

Pedestrianism was not the exclusive domain of men, though. Emma Sharp (1832 to 1920) was an athlete famous at the time for her feat of pedestrianism. She completed a 1,000-mile walk in 1,000 hours, the event first completed by Allardice in 1809. She is thought to be the first woman to complete the challenge, finishing on 29 October 1864, having started on 17 September. She is reported to have dressed like a man for the event, and to have used the proceeds of the walk, which exceeded £500, to set up a rug making business.

A report of the event is available on the web,2 which includes the following detail:

She took the same approach as Captain Barclay [Allardice] by walking a roped off course of 120 yards for 30 minutes at a time, which was equivalent to about two miles, before taking a 90-minute break. She would continue this routine for six weeks straight, walking day and night, until she completed her last mile.

Others threw burning embers in her path, some tried to drug her food, and still others simply resorted to trying to trip her at random times. As things escalated, for her protection, eighteen police officers disguised as working citizens were assigned to her on the final days of the race. In addition to that, during the night, a helpful citizen walked in front of her with a loaded rifle. Emma also walked the final two days with a pistol, which she had to fire in warning a reported 27 times in total to ward off unruly spectators.

She was not universally welcomed, then. She was an early example of someone pushing herself to overcome what was put before her. Despite doing virtually no training for the event, the only major physical issue Sharp experienced during the walk was painfully swollen ankles early on, but that soon went away as the days went on. Initially the female pedestrians astutely exploited the advantage of novelty, and Emma Sharp was not the only female pedestrian of note.

When the Olympics were revived in 1896, women were again excluded. Despite this, Stamata Revithi became the first woman to run a marathon when she covered the Olympic course from Marathon to Athens. Revithi ran one day after the men had completed the official race, and although she finished the marathon in approximately 5 hours and 30 minutes and found witnesses to sign their names and verify the running time, she was not allowed to enter the Panathinaiko Stadium at the end of the run. She intended to present her documentation to the Hellenic Olympic Committee in the hope that they would recognise her achievement, but it is not known whether she did so. No known record survives of Revithi’s life after her run. According to contemporary sources, a second woman, Melpomene, also ran the 1896 marathon course. There is debate among Olympic historians as to whether or not Revithi and Melpomene are the same person.

Societal disapproval of female runners was not universal though. Women among the Tarahumara in Mexico ran for hours without coming to any harm, as did many Native Americans, it being part of their chosen lifestyle.

In 1919 Alice Milliat started discussions with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) to also include women’s track and field athletics events in the 1924 Olympic Games. The suggestion was turned down. On 31 October 1921, Milliat formed La Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale (FSFI) with a plan to oversee international women’s sporting events. Milliat organised a competition in 1921 called the Women’s Olympiad in Monte Carlo; further editions were held in 1922 and 1923, and then in 1924 the Women’s Olympiad was held at Stamford Bridge in London. The IOC objected to the FSFI using the word Olympiad in the title of its events. After further negotiations the IOC and the IAAF agreed to include five women’s athletic events in the 1928 Olympic Games, and in exchange Milliat altered the title of the FSFI event to Women’s World Games. They didn’t include any endurance events.

Thirty years after Revithi’s run in Athens, Violet Piercy of Great Britain was the first woman to be credited with a world best time for the marathon, when she clocked 3-40-22, in what appears to have been a solo effort on 3 October 1926, although historians have questioned its veracity. On 16 December 1963, American Merry Lepper ran a time of 3-37-07 to improve slightly on Piercy’s record, having gatecrashed a marathon race. To add further confusion to the matter, sources such as the IAAF and ARRS (Association of Road Racing Statisticians) do not agree on details of some of these early marathons, or indeed recognise their existence in some cases.

Things did not move on smoothly for women in the Olympic movement. In 1928 women were allowed to compete at the Olympics at just five events: the 100m, 4 x 100m relay, high jump, discus and the 800m. One of the women’s races at that Olympiad, held in Amsterdam, set things back dramatically.

There was controversy surrounding the 800m race, stemming from the perception that nearly all the women collapsed upon finishing the race, which took place on 2 August 1928, with nine women starting and finishing the race, with six runners breaking the previous world record. Lina Radke of Germany won the gold medal, finishing in 2 minutes, 16 and 4/5 seconds, a full seven seconds faster than the previous world record, which Radke also held.

The media, at least in part, were responsible for stirring up the controversy and many newspapers reported the event as a disaster. Sportswriter William Shirer reported in the Chicago Tribune that, ‘five women collapsed after the race and that Bostonian and fifth-place-finisher Florence MacDonald needed to be “worked over” after “falling onto the grass unconscious” at the end of the race’. In the eyes of the male-dominated media, these competitors had shown that they were too weak to complete two laps round the track.

The background of the inclusion of women’s track and field events in the Amsterdam Games also provides some insight into the controversy surrounding the 800m race. The traditional views of the IOC, championed by the founder of the modern Olympic movement, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, excluded women from competition and made the addition of events for women extremely difficult. Baron de Coubertin believed that ‘allowing women in sports would harm their feminine charm and degrade the sport in which they participated’. The 800m was not re-introduced to the women’s programme until the Rome Olympics in 1960.

In Great Britain, there had been a race up and down Ben Nevis, the highest mountain in Britain, nearly every year since 1895. Kathleen Connochie was the first woman to run the race, in 1955. Kathleen was no stranger to the race as her father was the medical adviser, and the acting vice-chairman of the organising committee (Duncan MacIntyre) was a family friend.

Her family were all sitting at home one evening about three weeks before the race talking about the arrangements. Out of the blue, Duncan MacIntyre said to her: ‘Do you think you could run the Ben race yourself?’ She replied: ‘I don’t see why not!’ Immediately, Duncan offered to train her.

Her son, Duncan Macpherson, recently re-told the story to me. ‘The following morning at 8am Duncan MacIntyre was there to take her out running. They ran in out of the way places so as not to be seen. Then went onto the hills and on to the Ben two weeks before the race.’ For the next three weeks, Kathleen and Duncan trained in secret on the peat track at the back of Fort William, and in the forests between Torlundy and Leanachan. Although she didn’t want people to know that she was running, Fort William was a small place, and eventually people began to find out, and Kathleen Connochie soon became the focus of attention in the build-up to the race.

Duncan Macpherson added that, ‘she was entered as a woman, and was accepted’, but the plan was nearly scuppered by the Scottish Amateur Athletic Association (SAAA) bureaucracy. A message had arrived before lunchtime on race day to say that Kathleen was being forbidden to run. Duncan MacIntyre was furious and withdrew from the race, with others supporting his stance. An approach was made to the race committee, and they agreed to make the race facilities available to Kathleen, who was set off two minutes after the main body of runners.

Hugh Dan MacLennan’s Ben Nevis race history3 reported the race:

The day itself was dry with a light wind. There was mist, but no snow on the summit. Eddie Campbell won the race in one hour fifty minutes, and Kathleen came home in three hours and two minutes. Kathleen said at the time she would never forget the surge of adrenalin as she approached the finish field. ‘I felt really fresh, and we had a great time coming down the hill. At one stage Duncan disappeared to go and wash himself having fallen in a bog and I know there was consternation at the finish when it was announced that we had been separated. Then I passed the SAAA official on the way down and that gave me a lot of pleasure. I still have the ladies’ washbag I was given as a prize. It is a treasured possession.’

Happy with the outcome, Kathleen Connochie never ran the race again, although she and her family continued to support it. She said: ‘I had done what I set out to do, and I didn’t really see any point in doing it again. It was for other people to pick up the challenge and we got a lot out of it as a family over the years. I suppose in many ways I did it for Duncan. It was fun and we have all enjoyed every minute of it.’

Having Kathleen Connochie running in the 1955 Ben race was quite probably of huge benefit to the race itself. The media exposure it attracted may well have been responsible for the fact that double the number of runners completed the course the next year. However, women weren’t officially invited to run the race until 1980.

Moving on to the challenge of the marathon: Dale Greig became the first woman to break 3 hours 30 minutes for the marathon distance. Her record, of 3-27-25, was set on 23 May 1964 at the Isle of Wight Marathon, where she was followed around the course by an ambulance. Greig was made to start four minutes ahead of the men. This meant that her run could be called a time trial, rather than a race against the men. It was her first attempt at the distance. She was also the first woman to run two ultramarathons: the Isle of Man 40 in 1971 and the 55-mile London-to-Brighton race in 1972 – seven years before female competitors were officially allowed.

The Secretary of the sport’s governing body, the Women’s Amateur Athletic Association (WAAA), Marea Hartman, was concerned to protect the ‘rules’ that were in place at the time, and certainly saw no need to encompass change in women’s sport. She was quoted in the Daily Express,4 two days after the event (i.e. in 1964), with this position statement. ‘We have no races over [more than] 4.5 miles. It’s felt these distances are too much for women. As for women running against men – No. The discrepancy is too great.’ The Isle of Wight Marathon race organisers, Ryde Harriers, were reprimanded by the area athletics authority for allowing a woman to run in their marathon.

Before 1972, women had been barred from the most famous marathon outside the Olympics – the Boston marathon – although that rule did not keep women from running it. In 1966, Roberta Gibb hid behind a bush at the start, sneaking into the field and finishing the race in an unofficial time of 3-21-25, to become the first woman known to complete the arduous Boston course. Gibb had been inspired to run by the return of her race entry with a note saying that women were not physically capable of running a marathon. ‘I hadn’t intended to make a feminist statement,’ said Gibb. ‘I was running against the distance [not the men] and I was measuring myself with my own potential.’ Roberta Gibb’s run has largely been forgotten because of the fuss made over the next woman who ran the Boston Marathon.

The following year, number 261 in the Boston Marathon was assigned to entrant K. V. Switzer. In lieu of the pre-race medical examination, Switzer’s coach took a health certificate to race officials and picked up the number. Not until two miles into the race did officials realise that Switzer was a woman, twenty-year-old Kathrine Switzer of Syracuse University. Race director Will Cloney and race official Jock Semple tried to grab Switzer and remove her from the race, or remove her number, but her teammates from Syracuse fended them off with body blocks. Switzer eventually finished the race after the race timers had stopped recording, in 4-20. Although Switzer knew that they were not expecting women to enter, she has claimed that she had not used her initials on the entry form to deceive the race officials, but was merely a fan of J. D. Salinger and liked the sound of her initials. While Switzer was creating a stir with her unauthorised entry, Roberta Gibb again ran the race, this time being forced off the course just steps from the finish line, where her time would have been 3-27-17.

Photos of the race officials chasing after Switzer appeared in the national papers the next day and brought the issue of women’s long-distance running into the public consciousness. The officials defended their actions, saying they were only enforcing the rules – that forbade men and women from competing in the same race and barred women from races of more than one and a half miles.

‘I think it’s time to change the rules,’ said Switzer. ‘They are archaic.’ Switzer’s story and the surrounding publicity had made the quest for equality in road racing for women a political issue. Coming as it did in the midst of the women’s liberation movement, it galvanised women in the belief that it was time for change.Soon race directors wanted her (unofficially) in their races, and she was given unofficial trophies at several events. In May 1967, in Toronto, thirteen-year-old Maureen ‘Moe’ Wilton was paced to a 3-15 marathon, then the world best for women, in a race Switzer also took part in.

In the late 1970s, Kathrine Switzer, retired from competitive running, and was one of the people who led the way toward the inclusion of a women’s marathon in the Olympics. In 1977, Switzer, then director of the Women’s Sports Foundation, met an executive for the Avon cosmetics company who told her the company was interested in sponsoring a running event for women. Switzer wrote a seventy-five-page proposal describing how Avon might sponsor a series of events, and the company liked her idea so much they hired her to plan the races. The first Avon International Marathon was held in Atlanta, Georgia, in March of 1978, drawing women from nine countries. On 3 August 1980, 200 women from twenty-seven countries ran in the third of the Avon sponsored marathons. It was held in London, starting in Battersea Park, and was won by New Zealander Lorraine Moller in 2-32-44. This was one year before the London Marathon was launched, which really opened up the event to mass participation by women.

In 1979 the International Runners Committee had been set up to campaign for the inclusion of the marathon, 3000m, 5000m and 10,000m in the IAAF World Championships and the Olympics, and in 1980 the American College of Sports Medicine had released a statement in support of the creation of the women’s Olympic Marathon. It stated:

There exists no conclusive scientific or medical evidence that long-distance running is contraindicated for the healthy, trained female athlete.

After years of hard work and lobbying by passionate female and male athletes alike, the women’s Olympic Marathon was finally included in the Los Angeles Olympics, in 1984. Joan Benoit became the first female gold medallist in the event. This was eighty-eight years after the first men’s Olympic marathon had taken place.

Joan Benoit later said of running into the Olympic stadium: ‘Once I passed through that tunnel, I knew things would never be the same.’ The women that followed on from Kathleen Connochie also ensured that fell and mountain running would never be the same again.

CHAPTER 2

Beginnings

Opportunites and Competition Open Up: The 1950s and After.Profiles: Carol McNeill, Joan Glass

‘The fields had some very narrow stiles, and some very odd things happened at these stiles.’

Such was the scene at an early running competition on the fells, which can be traced back to the 1860s. The first ‘fell race’ was the Hallam Chase, which has been hailed as the sport’s oldest amateur race, being first run in 1863. The Hallam Chase is best described as a cross-country race, which was originally held over a 10-mile course on the edge of Sheffield. The Grasmere Guides Race was first held in 1868, going to the top of Silver Howe and back initially. It was a professional race, with three pounds being the first prize.5 The full history of these and other early fell races, and the amateur/professional divide, is documented elsewhere by this author,6 and is not directly relevant to the theme of this book, as women were not allowed to compete in those early amateur or professional races.

Towards the middle of the twentieth century, we see women beginning to assert themselves by competing in off-road endurance events. Even before the exploits of Kathleen Connochie on Ben Nevis (in 1955), there had been a couple of cases of women being accepted into, rather than being turned away from, UK fell and mountain races.

The Lake District Mountain Trial was the first event in England to promote a women’s fell race. The event had been inaugurated (with a men-only race) in 1952. It was organised by the Lakeland Region Group of the Youth Hostels’ Association, to celebrate the group’s twenty-first anniversary. They had originally planned on holding it on just that one occasion. The event was a mountain challenge, starting at the Old Dungeon Ghyll and covering about sixteen miles, for YHA members – with the stipulation that they wore boots or stout shoes. It used one-minute interval starts, in the same way that cycle time trials have usually done, probably because it was suggested by Harry Chapman, who was a former racing cyclist.

It was such a success that it was repeated in 1953, to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. This time there was also a women’s race, going up Rossett Gill, across to Esk Pike and Bowfell, then back down the Band. It is worth noting that there were just fifteen starters in the men’s race. Bill Smith reported on the women’s event in his history of the sport:7

There were 4 competitors, of whom Jane Allesbrook of Cark-in-Cartmel was easily the fastest in 2-14-39, being accompanied by her two dogs; and she was followed by 17-year-old C. H. Mawson of Windermere in 2-46-12; Hazel Myers, assistant warden at Coniston Youth Hostel, in 2-48-30; and 41-year-old Mrs M. O’Hara, wife of the Coniston YH warden.

There was a women’s race again in 1954, over the same course. There were three entrants, Hazel Myers again, together with C. M. Bleasdale and M. Metcalfe (from Preston Harriers), with only Myers finishing, in 2-46-10. After that, Mrs Jane Buckley (of Kentmere) finished twenty-seventh out of a total of thirty-one competitors in 1956; and then there were three female entrants in 1968. The Lake District Mountain Trial Association booklet8 records that last event:

Three women were given special guest entries as another precursor to the Women’s Trial, but the course proved to be too demanding. LDMTA Records indicate all ran within sight of each other and that Carol McNeill of the Devizers, who was to win the Women’s Trial in 1991, retired at Slight Side while Sophie Rex and Hazel Hill, both of Southern Navigators, were timed out at Great Knott.

A patchy start to women’s competition, then, and still not really being welcomed by the organisers. Despite the ‘precursor to the Women’s Trial’ quote above, it was another decade before the women’s trial was run again. This was in 1978, by which time Sue Courchee was Organiser, a post sheheld for seven years.

Orienteering was ahead of fell running in its attitude to females. Southern Navigators, to which two of the competitors above belonged, was founded in 1965 by Chris Brasher and John Disley. The British Orienteering Federation (BOF) was established in 1967 and held the first British Championships that year. There was equality of competition right from the start, with both a men’s and women’s competition, won by Gordon Pirie and Carol McNeill respectively.

Carol McNeill was a competitor who went on to make a significant mark as a fell runner, and in orienteering (as she won the BOF Championships six times). She recalls that Lake District Mountain Trial in 1968. ‘We had been putting pressure on organisers to allow us to run. Sadly, none of us finished – it was from the Old Dungeon Ghyll, and I had to retire because of feeling ill. This was a real shame because I thought it would have fuelled the argument against women competing. It was a few years later when women were allowed in again.’

Carol McNeill

When I first contacted Carol she agreed to get out all of her fell running maps to help her to remember the past years, times and positions in events. She also dug out her training diaries as a further guide. Straight off she confirmed that she is still running competitively, and proudly noted that she had competed in twenty-six Mountain Marathons and many fell races. Although claiming not to have been a pioneer she was certainly challenging the status quo by pressuring the Lake District Mountain Trial organisers to be allowed to compete.

Carol was born in 1944 in Crosby, Liverpool. She trained as a PE teacher, taught in Wiltshire (where she started orienteering and running), then moved to Scotland to work in Outdoor Activities at the Benmore Outdoor Centre near Dunoon. She then moved to the Edinburgh University PE department; to the Dunfermline PE College Outdoor department; and then ran an outdoor centre for Dumfries and Galloway at Castle Douglas. She moved to the Lakes in 1983, eventually teaching at John Ruskin School, Coniston.

She was not a runner at school, mainly playing hockey and tennis. As an adult she carried on the hockey and tennis, and added orienteering, cross-country skiing and mountaineering. She didn’t start running until she was twenty-two years old.

She says now that she ran some cross-country and a half-marathon – all as part of her training and fitness for orienteering. ‘I was never at the front, I wasn’t a natural athlete, better at running over rough terrain than on roads. But I trained really hard from 1978 to 1993, averaging 50 miles a week with a peak of 80 miles per week in 1979.’

According to Carol’s records she next raced in a fell race at the Moffat Chase in 1978, aged thirty-four. ‘I think I must have done the Carnethy 5 when I lived in Edinburgh, which would have been sometime between 1969 and 1981, and also the Ben Nevis race. I do remember when they changed the Carnethy course. They started on the other side of the A702 instead of the school in Penicuik. When it was really foggy there was concern that the runners wouldn’t see the cars coming and vice versa.’

With her love of the hills, it was natural for Carol to run on them. Initially she trained with several other runners, some of whom ran on the fells, and she recalls there was general banter and encouragement to do some fell races. Despite the Scottish connection she only ran the Ben Nevis race once, in 1982, finishing out of the medals in 2 hours 1 minute. She was, however, there as well when the Ben race was cancelled due to thick mist in 1980. She came second (to Anne Bland) in the two-lap cross-country race the organisers put on instead.

Carol certainly hadn’t been training specifically for the fells by the time of her first race on the hills. ‘I was doing a lot of hill intervals as part of my training and running in the hills for fun. I started doing Mountain Marathons in 1976.’ She was a member of three orienteering clubs (Interlopers Orienteering Club of Edinburgh, then Solway OC, and then Lakeland OC) before she joined Ambleside AC around 1983. She has notes in her training log which show that she joined the midweek training runs there in the late 1980s.

Looking back on those early days, Carol didn’t have any specific problems with race organisers and their attitude to female competitors. ‘I can’t think of any in particular. There certainly weren’t any negative vibes coming through. There weren’t that many women at races in the beginning, but I never thought of myself as a pioneer.’

Whilst not being particularly active in trying to make changes happen, Carol was very aware of inequalities, particularly with regard to prizes. ‘I remember commenting at a Borrowdale race that winning a pair of socks didn’t compare well with the men’s rucksack or similar prize. Also, at a KIMM our winning socks (again!) undervalued our result – we got them changed for a fleece, which I still have.’

Carol emphasises that she took up running to train for orienteering, which she started doing in 1965. ‘Whilst in Scotland I ran in some fell races for fun and in 1983 I moved to the Lakes and increased the number of races considerably. I really enjoyed the contrast of trying to keep up with a pack compared to navigating on my own in O-races. All my training was aimed at and motivated by succeeding in O-races – right up until the 1990s when I was aiming to win the veteran category at fell races, and I did.’

Carol feels that her Joss Naylor Challenge was one of her most satisfying achievements. ‘I had a go at this when I was fifty-ish – soon after it was established. I was confident I could do it in the 14 hours allowance we had at that age but was sick going up Gable on a really hot day. I did finish but out of time (in 15 hours). I told myself I would wait until I had 24 hours to do it again. One does slow down with age. It wasn’t as easy as I had anticipated, although I trained with a small group doing sections. I had a couple of bad patches which I got through thanks to my support team.’

She also did the Bob Graham Round, in 1993, getting home just inside the 24 hours. ‘I was the oldest woman to do it at the time. I was forty-nine. I am not sure if that has been superseded – maybe Wendy Dodds has done it again?’ Wendy Dodds did a Bob Graham Round (a 53 Peaks at fifty actually), and Julie Carter a 55 at fifty-five in 2019, so Carol is no longer the oldest female Bob Graham Round completer.

Although she hasn’t done any other big rounds, she did do the Three Peaks Yacht Race a few times – Barmouth to Fort William – as a runner. Once with women runners (three women, three men), with Jean Dawes and Anne-Marie Grindley; then she raced with all women’s teams two or three times. She also did the KIMM every year from 1996 to 1998 and has been controller a couple of times.

Carol did the Lowe Alpine Mountain Marathon (LAMM) a few times, including Harris in 2019. She also did one mountain marathon in Norway with Ros Coats and tells a story from that event. ‘At one point we swam across a lake. The advantage was that we beat the Bloor brothers into the finish; the downside was that we had chosen a bad place where it was quite wide, and Ros declared she wasn’t a strong swimmer!’

When asked about her finest race or achievement in the sport, Carol McNeill says it was the Dunnerdale in 1991. ‘I was training for the Vets World Cup (Orienteering) in Australia, so I was training hard while the others were cruising through the winter. I was just enjoying the run when I caught up with Helene Diamantides and wondered if she was maybe ill. I asked her if she was OK and she said, “of course I am, keep going Carol you are having a blinder” (or something similar). Then some of the men started running with me to keep me going to the end. I was second behind Yvette Hague, in 48 minutes, which would be a good time even now.’ Not a win then but pushing herself to a great second place.

Carol adds that, although she set no race records, she did win the Lake District Mountain Trial once, in 1991, which she was really chuffed with. Having been second a few times she was pleased to win once. Of her twenty-six Mountain Trials – seventeen were Medium and nine were Short, which she started doing soon after that option was added and open to everyone. ‘On the web page they only count Classic and Medium. I was disappointed that they haven’t acknowledged the older people. Joss Naylor has done a few Shorts too.’

Talking through those that had the most impact on the sport in the 1970s and 1980s (male or female), she said: ‘Interesting – I can’t really remember. Joss of course, and Billy Bland. Selwyn Wright, Ros Coats, and Ruth Pickvance.’ But she had no doubt about whose overall record on the fells most impressed her, looking back. ‘Joss’s multiple achievements, which went on and on. Amazing.’

Still with unfulfilled ambitions, Carol McNeill concluded by saying she hoped to carry on doing the Lake District Mountain Trial (the short version). She had done the 2021 Short course and beaten Joss Naylor, although admitting that ‘he is a bit older than I am’. Carol McNeill was the first of the female athletes who pushed for their inclusion in events, and then went on to have a long and varied career as an orienteer and fell runner.

While there were scarce opportunities for fell race action for women in the 1950s and 1960s, several of the more walker-focused events did give openings for women to do endurance events. In a less competitive sense women had been leaving their mark much earlier. For instance, Louise Dutton was an exceptionally strong walker and was the first woman to walk the Pennine Way, soon after it was designated.

The Chevy Chase started as an organised walk in 1955 and had a formal runner’s class added in 1967. However, some male athletes had run it prior to that, and in 1962 sixteen-year-old Eleanor Puckrin won a women’s race over a much shorter course, with Eileen Dobson winning it in 1963. Reports of this event from later in the decade don’t mention female finishers.

Other events in which women were allowed to participate include the Fellsman Hike and the Lake District Four 3,000 Foot Peaks Marathon. The Fellsman started in 1962, and accepted women from 1968. It is a high-level traverse covering more than sixty miles over very hard rugged moorland. The event climbs over 11,000 feet, going from Ingleton to Threshfield in the Yorkshire Dales. The Fellsman list of winners, starting with Hazel Costello in 1968, became a veritable who’s who of female endurance athletes over the years.

The Lakes 4 x 3,000s9 (which is no longer held) started in 1965, and also accepted women from 1968. The route covers about forty-six miles with 11,000 feet of ascent but did include a good deal of road running. Pat Kenley (of Ulverston) won the first women’s edition in 1968, and then two more times in 1970 and 1973. The participation by a good number of women in these very long endurance events certainly shows there was an appetite for events for females to be added to the calendar. It is a sign of the times though that both Fellsman and Lakes 3,000s have the women’s information relegated to the very last paragraph in their respective chapters in Bill Smith’s Stud Marks on the Summits. Recent Fellsman organiser, Phil Carroll, confirms that at least seven female competitors completed the 1971 event, which is a good number for the time. Janet Sutcliffe was an early pioneer and was often competing at the Fellsman in the 1970s.

Even England’s national game was not immune to prejudice. There was massive excitement in England after the football World Cup win in 1966, with high hopes of a repeat in Mexico in 1970. However, the sport had not been welcoming of women’s involvement. In 1921 the sport’s governing body, The Football Association, had declared the game to be ‘quite unsuitable for females’, before barring women from playing on grounds belonging to affiliated men’s clubs. That ban was lifted in 1970 to allow a slow revolution in women’s involvement in the national game. There was soon to be a parallel change for women in fell and mountain running, which was more of an evolution than a revolution, as the sport became more formalised.

Two years after the Fellsman and Lakes 4 x 3,000s had accepted women into their events an organisation to manage fell running was set up in 1970. The Fell Runners Association (FRA) was initially run by men for men. It was reported that Brenda Robinson, the wife of one of the committee members elected at the first meeting, had to ‘wait outside in the car’ during that first meeting. However, it turns out that wasn’t quite the full story. It was actually worse, and Brenda wrote in The Fellrunner (the FRA magazine) that she was, ‘locked out of the car in the freezing car park playing with my seventeen-month-old son in the snow as dusk approached’.

The first FRA newsletter was published in September 1971, and on page three listed the first 117 members who had paid their 25p annual subscription. At the foot of that page was a footnote:

At least one enquiry has been received from a lady re membership! – How about lady members? – our constitution doesn’t specify sex!

Not exactly a welcoming message from the editor. For the record, Item 3 of the Constitution of the FRA, adopted at its opening meeting, states: ‘The Membership of the Association is open to all persons who support the Association’s objectives [my italics].’ These objectives were: ‘to encourage and foster better standards of Fell Running and allied mountain races in the United Kingdom and to provide service to competitors and race organisers.’ The Long Distance Walkers Association (LDWA) was founded in 1972 and offered long walking events for all, up to their annual 100 mile event.

The Autumn 1972 issue of The Fellrunner carried a two and a half page ‘recent history’ of the Ben Nevis Race by Jim Smith, and quietly mentions right at the end that the ‘women’s record stands at 3 hours 2 minutes, set by Kathleen Connochie of Fort William in 1955.’ Earlier the Press and Journal reported, in Sept 1971 in an article entitled ‘174 men – and 1 girl – in gruelling battle of the Ben’, on another female athlete running in the Ben Nevis race:

Fifteen minutes before the start, Miss Dale Greig, Tannahill Harriers, Paisley, already making a name for herself in marathon running circles, set out to try and beat the 1955 record of 3hrs 2 mins set up by a Fort William girl, when she limped in in 3hrs 3min 2sec with her shoes soaked in blood from blisters. First to greet her was that girl runner of 16 years ago, Kathleen Connochie, now Mrs George McPherson, wife of the Ben Nevis Race Association’s president.

The Welsh 1,000m Peaks race had first been held in 1971, with the full race going from Aber, taking in the four highest peaks in Wales and finishing on the summit of Snowdon. The first (shorter) women’s Welsh 1,000m Peaks Race, from Ogwen to the summit of Snowdon, took place the next year (1972), but was called ‘Class D for Women Mountaineers’, with Joan Glass entering in 1973. Carol Walkington and Joan Glass entered as mountaineers in 1974 and Joan won in 3-02-33. They returned the next year, finishing in the same positions, Joan winning with 2-28-50 to Carol’s 2-34-35. The women continued to run a shorter course for several years.

That Welsh 1,000 metres race, in 1973, was the first mountain event that Joan Glass had ever entered – as she had noticed that there was a class for ‘lady mountaineers’, over a shorter route than the men. She adds, ‘to my surprise and delight I won, and also the following year, but I didn’t train as such – just good days walking in the mountains.’

Joan Glass

The first thing that Joan Glass did when I contacted her was to offer the contact details for one of her long-time race rivals whom I had been trying to reach. She then proceeded to diligently respond to my multiple emails requesting details of her career and then asking supplementary questions as I sought clarification of the fine detail, particularly of challenging the Ben Nevis race organisers.

Joan Glass, whose maiden name was Gallagher, was born in Liverpool on 11 September 1939. As a youngster Joan didn’t really do athletics in school but was selected to run in the 400 yards and 200 yards hurdles for an inter-school meeting just before Easter 1953. She was selected on the Friday evening but on the Tuesday when she should have been competing, she was on her way to hospital, having been taken very ill, as she explains. ‘I didn’t return to school until the new school year in September. I had contracted osteomyelitis in my pelvis. It was originally thought to be polio.’

On returning to school, she was told she wouldn’t be able to do any sports. ‘Aghast, I did proceed to play hockey and netball, and had always loved swimming, which was a family favourite. I didn’t do any running before fell running. In fact, I came to running on the fells by default.’

Dennis, her husband, was the catalyst. He was organiser for an event for a YHA club (Liverpool Area Club) that they belonged to, that had first taken place in the 1950s. It was from Llangollen Youth Hostel to Maeshafn Youth Hostel. Joan says it was, ‘approximately twenty-six miles, consisting of some road sections and a super route over the Clwydian hills.’

The first event Joan competed in was this club ‘marathon’ in 1961 (but unofficially). ‘It was a mixture of walking and a bit of running downhill, and I ended up first female. Initially the route for the women was shorter, but after some persuasion we were able to do the longer route. My strength is stamina, not speed, so it suited me fine.’

Joan and Dennis Glass moved to Llanberis in 1964 to take up a position of managing Llanberis Youth Hostel and had three children, in 1965, 1969 and 1972. Joan comments that, ‘some good walking on the mountains was how I kept fit, with a baby in a papoose on my back.’

There wasn’t a running club in the area. The nearest was Wrexham Athletic Club, which they joined in order to enter some Lakeland races. ‘There were no fell races in North Wales. Dennis had joined the FRA in 1972. His number is 224. I joined later but was not a member for long, as hip problems interfered greatly with my running.’ Eventually, in September 1977, Dennis and Joan were among the founder members of Eryri Harriers.