Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

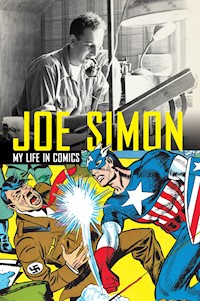

Before Marvel, before Captain America, before Simon and Kirby, and before comics there was Joe Simon. Born in 1913, the son of an immigrant tailor, he's been an artist all his life. A newspaper writer, photographer, and cartoonist, and the first editor at the company that became Marvel Comics, he was the man who hired Stan Lee for his first job. Entering the fledgling industry the year after Superman appeared, Simon instantly made a name for himself as a writer, artist, and editor. He and Jack Kirby created the iconic Captain America-their first blockbuster-before America entered World War II. More hits followed, including a bestselling military adventure series, the first romance comic created for an audience of young girls, and Simon's own satire magazine that was a favourite of Lenny Bruce. His exciting chronicle covers ten decades. It includes a stint in the Coast Guard during World War II, as well as his encounters with such colorful personalities as author Damon Runyon, prizefighters Max Baer and Jack Dempsey, comedian Don Rickles, Vice-President Nelson Rockefeller, and actors Caesar Romero and Sid Caesar. This is the comprehensive autobiography of an illustrator, an innovator, an entrepreneur, and a pioneer. Profusely illustrated with photography and artwork, much of it heretofore unseen, this is the chronicle of an American original.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 374

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Title Page

Dedication

The Great American Hero

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

My Bulletin Board

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

My Weirdest Cover

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Artist at the Mall

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Prologue

Also Available from Titan Books

JOE SIMON: MY LIFE IN COMICSISBN: 9781845769307E-book edition ISBN: 9780857687913

Published byTitan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark St., London SE1 0UP

First edition: June 201110 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Joe Simon: My Life in ComicsCopyright © 2011 Joseph H. Simon

Front cover:Captain America: Marvel and all related character names and likenesses are ™ & © 2010 Marvel Entertainment, LLC and its subsidiaries. All rights reserved.Photo of Joe Simon copyright © 2003 Joe Simon and Jim Simon. Used with permission.

Photos courtesy of Joseph H. Simon, except when otherwise stated. Copyright © Joseph H. Simon. Used with permission.Imagery on see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here; color section pages 3 (top), 7 (top). Marvel and all related character names and likenesses are ™ & © 2010 Marvel Entertainment, LLC and its subsidiaries. All rights reserved.Imagery on see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here, see here (right), see here; color section pages 2 (top), 3 (bottom right), 7 (bottom right). All characters, their distinctive likenesses, and all related elements are trademarks of DC Comics © 2011. All Rights Reserved.Photos on see here, see here, see here copyright © 2003 Joe Simon and Jim Simon. Used with permission.Image on see here copyright © 2011 Tribune Media Services.Image on see here copyright © 2011 The New York Times.Photo on page 243 courtesy of Joe Sinnott.Photos on pages 8 of the color section by Dana Hayward. Copyright © 2011 Dana Hayward. Used with permission.

The Comic Book Makers Copyright © 1990 Joe Simon and Jim Simon.

The right of Joe Simon to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

Editors: Steve SaffelJo BoylettConsulting Editor: Megan CounteyArt and photo restoration: Harry Mendryk, Dana Hayward

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at: [email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Harry Mendryk, Steve Saffel, and Tedd Kessler, without whom this book wouldn’t have been possible. My thanks to the Kirby family, Stephen Broussard, David Althoff, Mark Vaz, Mark Zaid, Michael Grossman, Scott Price, Georgina Ryan, and the entire team at Titan Books, including Nick Landau, Vivian Cheung, Katy Wild, Tim Whale, Jo Boylett, Martin Stiff, Natalie Clay, JP Rutter, Lizzie Bennett, and Bob Kelly.

More than ever, this is for Harriet

And for Jon, Jimmy, Melissa, Gail, and Lori, as well as my grandchildren Emily, Jedd, Jeremy, Jesse, Jillian, Joel, Megan, and Michael.

THE GREAT AMERICAN HERO

THERE WERE MANY INCIDENTS that inspired my search for the great American hero. A pivotal one occurred when I was eight or nine years old in public school in Rochester, a middle-class tailoring center in upstate New York. This was my first contact with a living legend, a fragile little old man, obviously bewildered, dressed in a blue Civil War uniform worn thin over the years.

I never learned the man’s name. Our teacher, a pretty young woman whose military knowledge was limited, just presented him as, “The Soldier.” That was enough for us kids—he was The Soldier, plain and simple, a veteran to be honored, though long past his fighting prime.

The old vet lovingly clutched a flag as tall as he was, holding it rigidly upright like an antenna.

He faced the class. Proudly he unfurled the flag—to the cheers of his eager young audience.

This was a banner I had never seen before. It had the same number of red stripes as today, four above the union, three below. However, the blue union area in the upper corner carried a single five-pointed star made up of 35 smaller stars.

At a much later date I learned that it was a popular flag at the time, called the 35-star Great Star Flag, similar to the 36-star flag that draped President Lincoln’s coffin. The company that made the coffin flag gave it 36 stars by mistake.

Yes, the nation confused us as much then as it does now.

The teacher came forward.

“Class, we are fortunate today to be addressed by a great American hero who brings to you an historic message.”

The little soldier stepped forward. Beginning with the student in the back left corner of the room, he extended his right hand, and shook the seated kid’s hand. As he did, he said these words:

“Shake the hand that shook the hand of Abraham Lincoln!”

He moved from desk to desk, shook every hand, and repeated the same message to each and all.

Wow!

Historic? More than that…it was iconic.

Our teacher sidled into a position in back of the vet. She pointed her finger to her forehead and twirled it. We all hoped it didn’t mean what we all knew it meant. We kids of Rochester, New York, were smarter than a lot of people thought we were.

So we paid her no mind. Our enthusiasm was evident, and the inspired old soldier was encouraged. He burst out into song.

“Oh, the old flag never touched the ground, boys. The dear old flag was never down!”

Mission accomplished. The children kept on cheering and the old vet kept singing as he marched out of the classroom, another battle won. Another great boost for a patriotic nation.

I would always remember the odd little fighting man as I continued in my life-long quest for the great American Hero. Eventually I would find him… and more.

You must have seen a few of them in your neighborhood—the ever-expanding, ever-exciting fantasy world of comic books.

CHAPTER ONE

SOMETIMES it seemed like we were all the sons of Schneiders. Jack Kirby, Will Eisner, and I—all of our fathers were tailors. Even Jerry Siegel’s father was a haberdasher. When you look back at it, the whole comic book industry seemed to stem from the clothing business.

My father, Harry Simon, was an immigrant from Great Britain. He came from Leeds, a major British clothing center famous for the manufacturing of wool, so it was only natural that when he came to the United States in 1905 he would land in Rochester, NY.

He looked just like Harry Truman, and I think he was 20 years old when he came to the United States with $5 in his pocket. At Ellis Island they asked him where he was going to live. He told the authorities he would be staying with his brother, who had arrived a couple of years earlier. His whole family had been moving here, one after the other, and he went into business with his younger brother, Isaac, who was also a tailor—a pants maker.

With a population nearing 175,000, Rochester was almost exactly the same size as Leeds. The third largest city in the state—behind New York City and Buffalo—it was the center of the United States garment industry, especially men’s clothing. We had all of the major companies back then—Bond Clothing Stores, Hickey Freeman, Fashion Park, and Stein-Bloch & Company. By the time I came along the population had already exploded to nearly a quarter of a million people. Bond employed 4,000 people, and the city’s entire clothing industry—which produced 1,500,000 suits and overcoats in 1919 alone—boasted a full-time labor force of more than 10,000 workers.

Harry Simon’s family in Leeds, England, 1901. Back row, left to right: Harry, Isaac, and Sara. Front Row, left to right: Irving, Lena, Hyman Samuel Simon, grandson Jack Taylor, and Etty Ruth Pollack Simon (with baby Rose).

There was always a lot of conflict between the factories and the laborers, who were openly recruited to join unions such as the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and the United Garment Workers. As soon as my father arrived he got himself into trouble as a union organizer and a socialist—“You take care of me, and I’ll take care of me.” The manufacturers didn’t like it. I think my father lost some jobs because of it, but he just went into business for himself and worked out of his own home.

The big clothing factories are gone now. As far as I know, there’s only one major suit maker left—Hickey Freeman. But back then there were a bunch of factories, they were huge, and to my father it seemed as if the streets were “paved with gold,” as they used to say.

My father often had his shop in the front room of the apartment he rented with my mother, Rose. It was a lot like the tenements in New York City on the Lower East Side, where Jack Kirby grew up. We didn’t call it an apartment, though. We called it a “flat,” as the English do. We had a railroad flat, where the living space went from front to back without any windows on the side. You only had windows if you were very lucky.

Harry Simon was a terrific tailor. He made my Boy Scout uniform. He made my suits from scratch. I wore one each time I went on job interviews. When Kirby first saw me, he said I was the first comic book artist he had ever seen wearing a suit.

It’s weird, but I never knew my mother’s maiden name. Many years ago, when a bank asked me for it in order to set up an account, I had to make one up, and it stuck with me ever since. Of course, for security purposes, I can’t reveal it here.

Rose was playing on a girls’ basketball team when my father met her. The sport was a very different thing in those days. The women would wear these bloomers, and they’d each be assigned a position on the court. Under the rules, they weren’t allowed to stray from that spot, so they would just pass the ball to one another. I think it was so they didn’t have to run—women were considered very fragile back then. I have no way of measuring how fragile Rose was (or wasn’t), but she was a tall woman. She was playing in a game there in Rochester when my father first saw her, and he fell in love. Soon they were married, and then they had a daughter—my sister Beatrice—who was born in 1912.

Nine months later my mother was pregnant again.

My mother’s cousin, Little Izzy, was a pharmacist in Rochester. His name was Izzy Rosenthal, and he had a very nice drug store on Joseph Avenue at the corner of Baden Street, not far from the trolley stop. He did very well, and when my mother learned that she was pregnant, she went to him for medical advice. Since she had to work—she was a buttonhole-maker in the clothing factories—and she already had a baby, she was terribly worried that she couldn’t afford another child so close in age. So she went to Izzy for help. Even now I can see what a problem it must have been for her.

Harry Simon in 1905, the year he arrived in the United States.

She consulted with Uncle Izzy.

“We have to get rid of this baby,” she pleaded, meaning me.

“I’ll give you a pill,” Izzy said.

He prescribed her an aspirin. So you see how I dodged a bullet, and was born in 1913—on October 11—in Rochester’ Strong Memorial Hospital.

A lot of my father’s family was there in Rochester. He had a cousin named Hymie—tall, trim, and handsome, the kind of man women used to swoon for. Hymie was the family pet. So when my mother gave birth to me, my father completed the birth certificate without consulting her, and named me “Hymie Simon.” He brought it back, and my mother couldn’t read it. Eventually she figured it out, and flipped. Turns out she wanted me named after her brother, Joseph.

Now her Joseph, she said, was a Russian Cossack who had fallen off of his horse. The horse trampled him in the head, and he died. Nobody has ever believed that story, though. First of all, I don’t think they had any Jewish Cossacks. Whether they did or not didn’t really matter—the bottom line was that she wanted me named Joseph, and she didn’t want me named Hymie Simon. At least if it had been “Hyman” Simon, she said, it would have rhymed and sounded pretty good, but Hymie Simon…

No, she just called me Joseph, and after a while it stuck.

Yet that’s not what my birth certificate says. To this day it hasn’t been corrected, not social security-wise, veteran-wise, or for anything else. And rather than fight it, I just let it go—even though it means I can’t ever get a passport. At one point I asked my son-in-law the lawyer if it would cause any problems after I pass on, and he said no, not unless there’s fraud committed. So that’s where I stand.

I’m Hymie Simon.

I’ve never told that story before, and you know why? Because I was never old enough to tell that story—it was too embarrassing. I guess I’m old enough now.

We never had middle names in my family, either. We couldn’t afford middle names. But I took the “H” from Hymie and I made it into Henry: Joseph Henry Simon, Joseph H. Simon. I picked up the “H”—it wasn’t there originally, but Hymie was there.

What can I tell you?

As I said, my mother was a tall woman, slim, and my father was maybe an inch taller than she was—he must have been about five-feet-ten at the most. She wasn’t much of a reader, and didn’t communicate well in writing, but she spoke perfectly well. She was also a great singer—at least so they told me. At every party Rose Simon would get up and give these screeching performances that I simply didn’t comprehend. Everybody liked it, and she thought she was going to be an opera singer, but I couldn’t stand it. She thought I would be a singer, too, but then she had me sing for her one day while we were driving in the car.

“Let’s see what you sound like,” she said.

So I sang for her.

“Forget about it,” she said. She told me I was tone deaf, and that was that.

While I couldn’t stand her singing, I thought my mother was the greatest cook, and she delighted in cooking for me. She prepared these Russian dishes that were so delicious you couldn’t imagine them today. We ate a lot of meat, including a lot of brisket. I don’t know how healthy that was for us, but it was really wonderful. It certainly didn’t stunt my growth, and my mother was trying to put weight on me from as early as I can remember. I was the skinny kid—six-feet-three, tall, very strong, but skinny—and she tried everything. It got to the point where she tried feeding me Guinness stout.

We had a very loving family. Sure, my sister and I used to fight a lot, but that was normal. I took a lot of crap for her, and got into a couple of fights protecting her from neighborhood hoodlums. That’s what brothers do.

Early on my father was very religious. Passover used to be a big holiday, when the whole family would gather for the Seder dinner. Everybody would sit around the table; each would raise a glass of wine and say, “Next year in Jerusalem.”

And the next year would come around, and they would do the same thing.

“Next year in Jerusalem.”

I couldn’t figure out what the hell they were talking about. As far as I could tell, it meant that the next year the Jews would go to the Holy Land, today’s Israel. Some year, they were certain, it was going to happen.

Eventually my father turned away from religion, and by that time I had already turned away. I didn’t believe in a guy up there with a long white beard directing traffic. I’ve always tended to think for myself. When I was in school, though, I used to look over the books they gave us, with the stories, and these wonderful illustrations of God in his cloud. I loved the fact that they would put such beautiful pictures in a book.

I was an avid reader, and used to spend half my day in the library, the other half on the ball fields. I loved Mark Twain, and was fascinated by the story of Huckleberry Finn going down the river on the raft. I read some of the pulp magazines, but Jack Kirby was the pulp man—he used to read all of them, especially the science fiction titles. Mostly I read a different type of literature; I read all of the Tarzan books by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and all of the stories about the Knights of the Round Table. Horatio Alger, Jr., Tom Swift, and the Frank Merriwell mysteries—I read everything. There was one series called The Boy Allies that was set in World War I. Those novels in particular would have an impact on my career later on.

My parents actually tried their hand at writing a romance novel of their own. They loved to read those true confessions magazines put out by Fawcett and Hearst. We called them “flats”—magazines, but printed on newsprint. Well, one of them was sponsoring a contest, “Write us a story about how you met and fell in love,” or something like that. I vividly remember them sitting together at the kitchen table. My mother couldn’t write, so my father was writing it out by hand. (They didn’t even have a typewriter. The biggest purchase in their lives up to that point was when they bought a sewing machine for the tailoring business.)

I don’t think they ever sold that story—they probably didn’t even send it off—but the effort they put into it always stuck with me.

A lot of my inspiration came from the daily and Sunday funnies like The Gumps by Sidney Smith, Gasoline Alley by Frank King, and Mutt and Jeff by Bud Fisher. Herriman’s Krazy Kat was amazing. Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff were strong influences on me, and Prince Valiant in all of its excellence was about splendor beyond the imagination—Hal Foster was great. I really enjoyed Foxy Grandpa, a strip by Carl Edward (“Bunny”) Schultze, about a sly little fellow who always wound up outsmarting his two mischievous grandsons.

When Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy came along during the Depression, he was a no-nonsense cop who shot evildoers dead. It was some of the earliest violent killing in the strips, exactly the sort of thing that would get us in trouble in the 1950s with comic books like Justice Traps the Guilty. Gould’s audience, however, turned out to be of all ages including, they said, a young J. Edgar Hoover. They cheered when Tracy avenged the murder of his fiancée’s father.

Beginning in 1921, Ed Wheelan’s Minute Movies were my favorites—predecessors to the comic books of the future.

Even though it was a big hit, Dick Tracy wasn’t a favorite of mine. I was born into the realistic type of drawing, and Dick Tracy was a cartoon. Ironically enough, years later I wound up doing a lot of Dick Tracy covers for Harvey Comics when they reprinted the strip, and I got to know the character very well.

My favorite strip, however, was a thing by Ed Wheelan called Minute Movies. Parodying the films of the time, the series was like a comic book, really, with a cast of characters and a storyline that continued over several days until Wheelan had finished the sequence, and then he’d start all over again with a new movie. It wasn’t that I cared much for the artwork itself, but I loved that concept, and years later when comic books evolved, that’s exactly what they were—continuities with a beginning, a middle, a climax, and an end—a complete story.

Every city had several newspapers, and most were thriving—unlike the modern newspapers, which are dying out rapidly. They vied extravagantly for the most popular comic strips, which could do wonders for their circulations.

The highlight of each week came when Beatrice and I received our turn at the Sunday funnies, which were always in spectacular color. As soon as our parents turned them over to us, we sprawled on the carpet in the “front room,” as the living room was called, and devoured our favorite strips. Since our first-floor flat doubled as our father’s tailor shop, for business purposes the light fixtures on the walls had been converted from gas to electricity. Thus, on Sunday evenings we went back to the funnies under the light of those modern electrical luxuries.

Rochester was our world—we didn’t know of anything else except what we saw in the movies, where it was always Broadway, New York City, and William Randolph Hearst. I used to love reading about the big city, which by that time had more than five million people in it, and many of my hopes and dreams revolved around living there some day.

Eastman Kodak, the photography company, was a major manufacturer in Rochester, and its founder, George Eastman, was still alive when I was young—he was part of the curriculum we studied in school. There was an Eastman Theatre and an Eastman School of Music at the university. Rochester was a city of parks, and Kodak sponsored many of those, as well. They also funded a lot of clinics. I remember I used to ride my bike to the Eastman Dental Dispensary, where I think they ruined my teeth. It took me years to get them fixed.

George Eastman took his own life, actually, because of the pain caused by the same spinal condition that put his mother into a wheelchair. He left a suicide note saying, “My work is done. Why wait?”

The Jewish population of Rochester had strong ties to the tailoring business for many years. The owners of the companies were German Jews, and most of the factory workers were Jewish, too. As far as anti-Semitism, we all learned to live with it the way other minorities have learned to live with their problems, even today. Early on I understood what integration and segregation meant, because it was understood that we wouldn’t move into this section, we wouldn’t move into that house, and so on. But rather than overt anti-Semitism, it was in a relatively hidden form. Maybe you didn’t see it, but you knew what was going on. You’d go to a real estate agent and he’d say, “You won’t be happy here.” That type of thing.

So America has always had a problem in that respect, for the Jews, for the Irish, for lots of folks. But even when I was a kid I always thought people were nice. I had a tremendous respect for patriotism, and pride in my country. I think that was a big part of me when I went into comics. In my mind this was the greatest country ever, these were the greatest people ever.

Some of them didn’t like us?

No problem.

My family used to have a lot of money problems, though, even before the Depression, and I always had to contribute to the household income. There was a time when I was selling newspapers and no matter how cold it was, we used to get up early in the morning and meet at a coffee shop where we were given our newspapers. We’d have our donuts and milk—I was too young for coffee—and then we’d go off to sell the papers in front of the clothing factories. Where we met would change from week to week—we had to move on when each coffee shop got sick of us taking up space. Sometimes it would just be a street corner.

I would have been roughly 14 or 15 at the time, so this would be about 1927 or 1928.

I frequently sold my newspapers at Bausch & Lomb, a worldwide optical conglomerate that also made microscopes, binoculars, and camera lenses. We used to live about a block from the factory, near the railroad tracks that led to it. There would always be wondrous glass treasures that fell off the trains and landed beneath the trestles—a kid could spend endless hours exploring there.

Bausch & Lomb was huge in Rochester. Beginning with World War I and again during World War II they were granted a bunch of government contracts to manufacture things such as field glasses, searchlight mirrors, periscopes, and torpedo sights. But that didn’t really make a difference to me—not at the time. What I remember is that we used to go right into the lobby of the building and sell our papers for two cents…They were two cents!

Little did I suspect that later I would get into the newspaper business as a writer and cartoonist. One day I would create a group of newsboys who would become nationally famous comic book heroes.

Yet life wasn’t all work, and I’d say that I had a happy childhood.

All my life, I’ve loved women—but I was too shy back then to do anything about it. That was one reason I liked to go to the library, because it was where the pretty girls would go a lot. I even remember that I had a crush on this one girl all through school. Her name was Marion. I think she liked me, but to this day I’m not sure if she ever really knew how I felt. She blushed a lot when I looked her way, though.

I had a lot of friends, and I was always managing or playing on the sports teams. I don’t think there was little league baseball back then—that didn’t come along until the late 1930s—so we organized our own baseball league. We didn’t have football, either, but for an entirely different reason. The year before I went to high school, Rochester had three players who died on the high school football teams, so football had been barred from our schools. But we had everything else.

Selling newspapers at the Bausch & Lomb plant helped a lot when Simon and Kirby created the Newsboy Legion.

Basketball was an important part of my life, and I got into the sport when I was very young. I remember playing in the basement of a building, probably a school, where the ceilings were no more than eight feet high. There was no dunking, that’s for sure—it wasn’t high enough to dunk. And yet my friends were always struggling to get onto a team, and to get into the game. They had the Catholic kids there, and the Irish. We always used to get into fights with the Irish kids, but the Jewish kids weren’t there to fight—they were there to play basketball. So when the fight would start the Jewish kids would just sit down on the floor, ending the conflict before it could go anywhere. We played some black teams, too, and when you ran into one of those players it was like running into a steel scaffold.

We had one black kid in our gang—“gang” meaning the athletic teams. His name was Bobby Bray. His brother was the president of the June 1933 class at Benjamin Franklin High School, where I went as a senior. There weren’t a lot of black people in our area, and Bobby lived near downtown, off of one of the main streets. He was part of us, as far as we were concerned—he was no different from the rest. You say something wrong about Bobby and you’d have to fight the whole gang.

I managed the basketball team in high school, but I didn’t play on the team. Managing was tough in those days. You had to arrange for transportation—find somebody with a car to take the kids to away games. It wasn’t easy. Back then I used to sell the tickets for the games. I’d split the money with the other players. It was really a matter of establishing connections.

We had a guy on the team who was six-feet-six. His name was Paul Williams, he was our center, and he was considered a freak because he was so tall. I was just six-feet-three, so I was a sub-freak.

I went to movies as often as I could, although back then they didn’t even have sound—they were black-and-white with captions. They’d have a guy playing an organ, right there in front of the screen, down where he wouldn’t get in the way. I remember the first movie that truly impressed me was The Jazz Singer with Al Jolson and May McAvoy. That was the first sound movie. In it, Jolson plays the son of a cantor—the person who leads a congregation in prayer—who abandons his father’s Jewish tradition to perform modern jazz (circa 1927). The Jazz Singer drew huge audiences, many of whom scanned the theaters to see where the phonographs were hidden.

Years later, the movie that impressed all of us comic book guys was Citizen Kane, the film Orson Welles made about William Randolph Hearst, with all his weird angle shots and different film noir techniques. Those of us who were in the comic book business at that point—Citizen Kane was released in 1941—all went to see it over and over again. It influenced a lot of our work for many years.

Although I grew up in Rochester, that wasn’t the only place we lived. From time to time we would move to where my father’s relatives or my mother’s relatives lived—Chicago, Detroit, wherever they would take us in. We were like homeless people for a while. Both of my parents had large families—I know I had lots of aunts and uncles on both sides. When I was ten years old we moved to Chicago and stayed there for a year. It was 1923. My father opened a mom-and-pop store, you know, an ice cream and candy store.

The kids in Chicago didn’t take to me, so every day I’d have to find a different route to and from school, always crossing the railroad tracks that were right behind our house. But they’d find me, and give me a beating. They would grab my roller skates, I’d fight for them, and then go back home with bloody knuckles. I remember my father called in the police once to get my bicycle back. He looked at those bloody knuckles and he was so proud of me. A little Jew fighting those tough Irish kids in Chicago. It wasn’t a race thing, however, it was just a turf thing. We lived in a crummy neighborhood.

But then we returned to Rochester. I suspect it was because there was more needle trade there, as they used to say. Those were the years leading up to the Great Depression, but there were lots of people already struggling for money. All through those times I remember guys on the street selling apples, and I remember the milkman who used to come with his horse and buggy in the morning. He’d leave the milk by the front door, and after we’d drunk it we’d leave the empty glass bottles for him to pick up. As a little boy, that was all I knew—it was life then. I had no concept of what it would be like in a booming economy.

My first real brush with politics came in the early 1930s, at the height of the Great Depression, when both of my parents got paid to work on the first Franklin Delano Roosevelt campaign. Both my mother and my father were avid FDR supporters, working out of the tailor shop. My father would go out and talk to people on the street, or go door-to-door to talk to them in their homes. He and my mother would send out brochures and letters and make phone calls.

All my life my father would sit around smoking cigars and talking about politics. He’d finish a cigar, crush up what was left of it, put the tobacco in a pipe and keep going.

It seemed like everybody was a democrat then. When FDR ran for president he was going to solve all of our problems. We truly believed.

CHAPTER TWO

I DON’T REMEMBER when I went to drawing.

I was always interested in writing and artwork, at the top of my class and semi-famous in school. Every Christmas the teachers would send me around from classroom to classroom to draw Santa Claus on the blackboard using colored chalk. I was maybe eight years old. It all came very easily to me.

The rest of the year, I’d sit and make these elaborate pencil drawings of cowboys or horses or whatever the kids wanted, and sell them for a penny or two. Even as a young boy I was a working artist.

My father encouraged me, but my mother didn’t think I could make a living that way.

“Artist, shmartist,” she’d say.

Because we moved frequently, I went to more than one high school, including East High and Monroe High. I was a senior at Benjamin Franklin High School, which opened for business in 1930—I think we were in the first class there. Franklin began as a junior high school, and was quickly converted into a junior-senior high school. I’ve been told by my friend Michael Grossman that it’s been broken up into several schools now, including the Global Media Arts High School, where they’re particularly interested in my career, especially in light of the Captain America movie.

When I was in high school, however, I didn’t take any art classes, yet I was still the school illustrator—always drawing. The school newspaper was where I had my first comic strip published and encountered my first creative controversy. Done in brush and pen, my strip was sexual in nature, though very, very naïve, all I can recall is that it said something like, ‘Just between you and me and the lamppost,’ and it had something about kissing. Very innocent. But I was admonished for it later.

I was anxious to work for print, so I did artwork for the 1932 yearbook, called The Key. Next to my photograph there’s a little poem:

Joe Simon is an artist rare;His works draw tears and fun;We’ve lost the count of cards he madeAfter reaching ninety-one.

I did one strip and several standalone gray-tone tempera illustrations for the title pages in The Key: sports, music—the whole gamut of the curriculum. They were similar to the splash pages I would later do for comics, and it was the only time I tried a technique based on art deco—the futuristic style that was gaining popularity at the time. One of the best examples of art deco is the Chrysler Building in New York City.

Two universities saw the illustrations I had done and contacted the school to buy the rights to use the artwork in their own yearbooks. Each university paid $10 for the rights, and the high school faculty held a meeting to determine whether the school should keep the money or if it should go to me. I won by a single vote, and my professional career was born.

There was a girl who saw this picture, taken during my high school years, and said, “You were Sinatra skinny!”

The Key included one comic strip, predicting the future in store for some of the students.

There were a couple of artists who came to Rochester from New York to take their vacations. They always had their little sketchpads with which to draw people on the streets, in the train station, on the busses, even leaning against the lampposts. I must’ve seen them doing it, and I tried doing the same thing. It was the first time I ever attempted anything like that. I learned a lot, especially since I hadn’t had any formal art training.

While I was the art director of the school newspaper and the yearbook I got a call from the Chamber of Commerce in Rochester. They needed a cover for their magazine, and maybe some interior illustrations, as well. They had seen my work in the school paper and yearbook, and they asked if I would be interested in doing some work for them—although without payment.

“Sure, I’d love to do it,” I told them. I was, what, a senior in high school?

And when the other guys in the school art department heard about it they tried to steal the work away from me, calling the Chamber of Commerce and telling them they were better than I was. I had a bunch of guys fighting with me over free work!

“Well, why didn’t you do the illustrations in the yearbook,” the guy from the Chamber of Commerce said to them. They had no response

Anyway, I got the job.

While I was in high school I knew a guy named Jacob Finklestein, who would have a very unique impact on some of my later work. He was our gang’s clown, and we had a singsong rhyme about him:

What do you think?My name is Fink,I’ll press your pants for nothing?

Fink was the direct inspiration for Housedate Harry, who starred in My Date Comics, beginning in 1947. In real life he would do exactly what Housedate Harry would do in the comics—make a date with a girl then spend the entire time on her sofa. She would happily bring him the treats—eats, soda—and he never had to spend a cent.

These pages from the Benjamin Franklin High School yearbook represented my one attempt at art deco.

Ralph Amdursky took this photo of me while we were in high school. Ralph became a fixture at the Rochester Journal-American.

Even before high school I ran with Abe Levitt, who was about six months older than I was. He was my best friend for many, many years, a great athlete and, like me, his father was a tailor—a Schneider. We had a whole gang of teenagers who did outrageous things together. We all had our different aliases. Abe was “Little” Levitt, I was “Gregory G. Sykes” (“G” for “Great”)—that’s how I would introduce myself.

Our group included a tall Swedish guy named Kenneth Stenzel who was voted the handsomest guy in the school, and he had a rhyme next to his photo in the yearbook, as well:

Kennie’s tall and Kennie’s fair;He’s the proverbial answerTo a maiden’s prayer.

We also had Morris “Bucky” Pierson. Later I would use his nickname for Captain America’s sidekick. Bucky had an older brother who was called “Buck.” They were both tough kids. Buck played in the American Basketball Association, for the Rochester Centrals, Rochester being in the center of New York State. They played such teams as the Boston Celtics at the great Rochester Armory. Big Buck Pierson was a starting guard for the Centrals and he often brought us to the games to watch and learn.

Bucky was my age, on my basketball team at Benjamin Franklin High School. In all those years we never knew Buck and Bucky Pierson by any other name. There were rumors that the family name was a shortened version of something like Piersonsky or Piersonovitch. A lot of families had dropped or shortened their European names when they emigrated to America. Pierson was a good American name, that was how Bucky was registered in school, so that’s who he was.

Those years were in the heart of the Great Depression. A guy had to scrounge around to make a couple of nickels. There was one summer vacation when Bucky and I lost track of each other for about three weeks. Then he showed up at my house “to say goodbye.” His face was almost unrecognizable, as he tried to smile through the scroungiest black beard I had ever seen. He explained that he had a summer gig. He had hired out to play for the House of David, a traveling basketball team. All players were required to wear beards—the longer, the better.

“The House of David,” I said. “What’s that, some kind of religious thing?”

Jacob Finklestein was the inspiration for Housedate Harry in My Date comics.

The basketball team included a lot of the gang: the unnaturally tall Paul Williams (third from left), handsome Kennie Stenzel (fourth from left), Bobby Bray (sixth), Bucky Pierson (eighth), and Little Levitt (far right).

“I have no idea,” he said. “It’s like…employment.”

Bucky came from an observant Jewish family, and a job was a job. We would miss him on the Sabbath when he organized the crap games in the back alley of the synagogue. But the summer flew by, school started. Bucky was back, shaved, and everything was normal.

It’s not as easy as one would suspect, tagging a new comic book character with a solid moniker. The name “Bucky” was perfect for Captain America’s crime-fighting kid buddy. Over the years I’ve read weird accounts trying to crack the secret codes associated with naming characters. One annoying analysis associated Cap’s Bucky with a “buck negro,” and insisted that it was politically incorrect. It’s nonsense, and it’s insulting.

Bucky was just a good kid on my basketball team. And a spunky crime-fighter.

I started smoking cigars when I was 17, even before I was working on newspapers. I wanted to smoke, and all of the guys were smoking cigarettes. But my mother thought it was a bad idea, so she started me into smoking cigars, like my father.

There was a guy named Calderon in our group. His father had a cigar business. They were the distributors to the mom-and-pop stores in the area. He was on our fringe because he was a Jew, but he was a Turkish Jew—we called them “turkey lurkeys.” Years later, Jack Kirby and I had a special deal to get our favorite cigars—Bering cigars made in Honduras—from Calderon’s company at a special rate.

We weren’t always nice people, however. We had some bums in the gang. We had one guy who dated a girl in a mob family, and he became involved in the “business.” I came back to town one time to find a story in the newspaper describing how he had displeased the mob. There was a picture of our guy, right there in the paper, his throat cut from ear to ear.

Like me, Little Levitt was involved in all sorts of activities in high school—he was in the class play The Ghost Story, he was on the soccer team and the basketball team. He went on to college. A lot of guys didn’t know where they were going at that time, but he did—he got a job with a butcher shop, and eventually he bought the place. Levitt’s business supplied a lot of restaurants all over the area, all the way down to New York City, so he did very well. He had a daughter who, like my own daughter, Lori, married an Irishman, and Abe eventually sold his business to the Irishman son-in-law.

He was a big hero in World War II, too, and received a bunch of medals for his service. He still lives in Rochester, where he recently decided to move into an assisted living apartment. Abe is the last surviving member of our basketball team.

Unlike Abe, I never went to college, even though I had a scholarship to Syracuse University. Several of my friends went there, and in the process they discovered the secret of how to get a free education—they matriculated at the Forestry School. You see, Syracuse boosters would come to Rochester, pick us up in their cars, and drive us to the university grounds where we were put up on campus. The divisions were very religion oriented in those days. If you were Jewish, you went to the Jewish frat house. There were racial biases, as well, and if you were black, well, forget it—it was like that.