8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

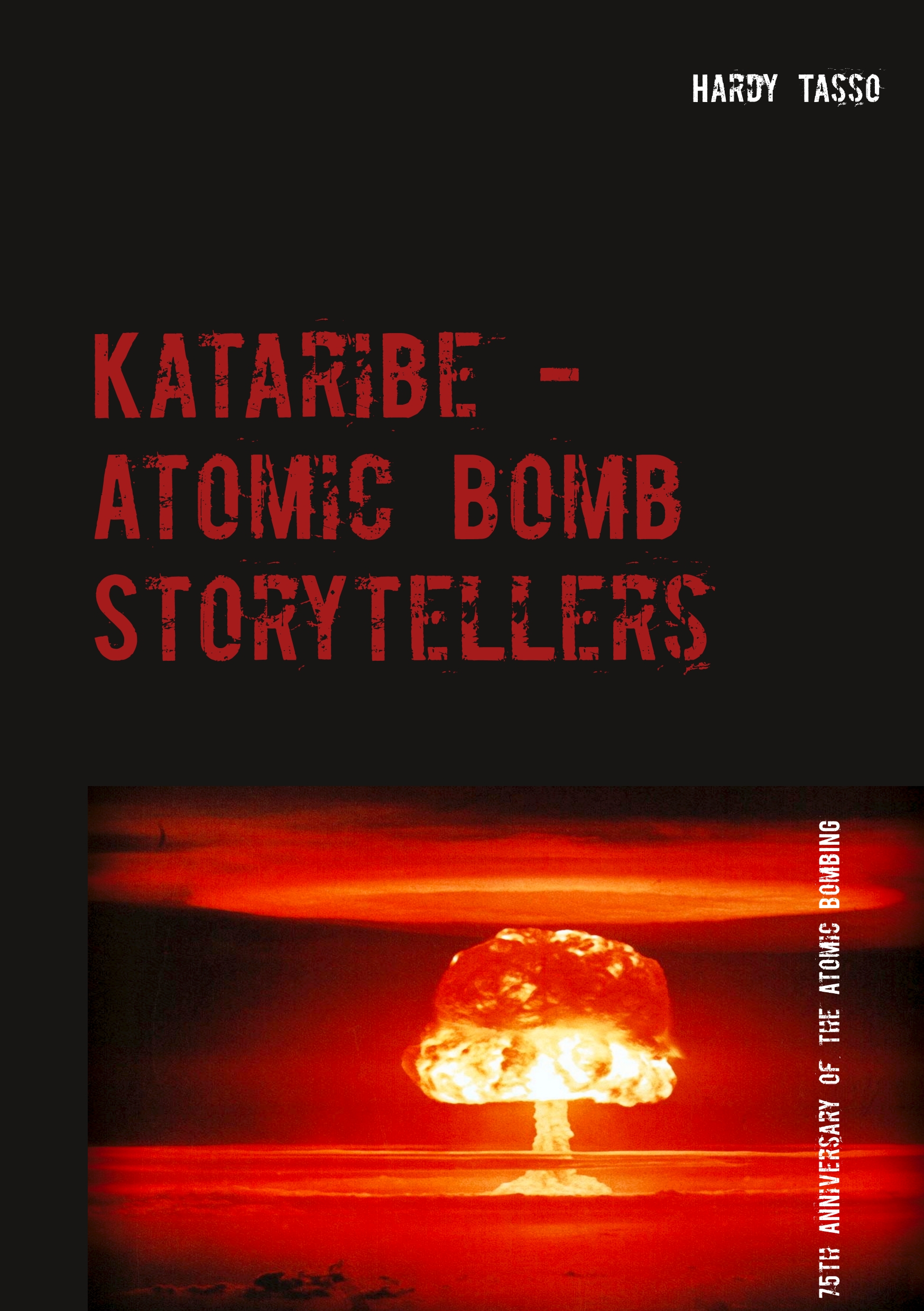

In August 2020, survivors commemorate the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. By then, however, most of the former survivors will have died. Only a few Kataribe, atomic bomb storytellers, remain to report on their experiences of August 1945. On the occasion of the 50th anniversary in 1995, several Kataribe in Hiroshima told me about their lives after the bombing. Here are their stories against oblivion. In order to protect future generations from the horrors of nuclear weapons.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 199

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

In memory of those kataribe who told me their stories. And with thanks for reminding us of their suffering, so that no more nuclear bombs will ever explode.

Content

Foreword

Why Hiroshima?

Approach in 1945

Yoshito Matsushige: As a Photographer, He Took the First Images after the Explosion of Little Boy

One Billionth of a Moment

Tadakatsu Ohtake: Chief of Social Affairs Section of the Red Cross Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital

Approach in 1995

Hiroshi Harada: Director from 1993 to 1997 of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Hibakusha

Kiyoshi Kuramoto: Physician in 1945 and Vice-Director of the Hiroshima Red Cross Atomic Bomb Survivors Hospital from 1995 on

Shizue Watanabe: Hibakusha

Fumitaka Mizuno: Deputy Director of the Peace Memorial Museum in 1995

Masayuki Kirihara: Hibakusha, former head of the German Headquarters of Mazda

Akihiro Takahashi: Hibakusha, Director of the Enterprise Division of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation in 1995

Naruto Heiwa and Shinzo Kishimoto: Survivors of the Second Generation—Hibaku Nisei

Suzuko Numata: Hibakusha

Visit to Hamburg

Kaoru Nakahara: Hibaku Nisei

Shinji Asakawa:Spokesperson of the Mayor in 1995, and Hajime Kikuraku: Staff Member of the Municipal Archives

Jogakuin Senior High School for Girls

Akira Tashiro: Journalist for the Newspaper

Chugoku Shimbun

in 1995

Ishiro Kawamoto: Founder of the Hiroshima Paper Cranes Club and Hibakusha

Addendum

Glossary of Some Terms

Picture/Photo Credits

References

Foreword

On August 6, 1995, 25 years ago, tens of thousands of survivors commemorated the two atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for the 50th time. It was their anniversary. On that 50th anniversary of the first and only dropping of nuclear weapons on human beings, I was in Hiroshima and I recorded on tape the experiences of a dozen of those 100,000+ people who experienced August 6, 1945 in Hiroshima and survived until 1995. In Japanese, the expression for those survivors is "hibakusha." This word consists of three words: "hi" for "suffering," "baku" for "bomb," and "sha" for "person." Suffer-bomb-person.

Many hibakusha have married and had children after the war. Over the years, these children often developed disease patterns like their parents: The radioactive radiation from the bombs has altered their genetic makeup and their health is often at risk. These descendants are called "hibaku nisei" in Japanese - survivors of the second generation. In this book, two hibaku nisei tell of their lives after the war – health-wise and socially.

Some of these hibakusha and hibaku nisei visit schools, travel to educational institutions in other countries, visit children and young people to tell them about their experiences during those two days of the atomic bombing on August 6 and 9, 1945. These "atomic bomb tellers" are now called "kataribe" in Japanese. They tell of the horror of the atomic bombs so that the events of those days in August never happen again.

Representatives of Hiroshima City Council proudly told me about the reconstruction of Hiroshima after World War II. At the Red Cross Hospital in Hiroshima, a physician showed me medical samples of organs of victims of the atomic bomb explosions: in a particular "tissue room," the samples are kept there today. Medical specimens of keloids are preserved in that room; keloids are very thick benign tumors that form on scars, which is why these scars are also called "bulging scars."

Employees of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum told me about their experiences with what has unofficially come to be referred to as the "Atomic Bomb Museum" about its visitors and the unusual exhibits. There are objects on display that tell in their way about the events of those two days in August and the years that followed.

From all these interviews, I created a radio broadcast for the West-deutscher Rundfunk in 1995, titled: "No Radiation—No Ashes. Hiroshima—50 Years Later". I have chosen this title according to Robert Jungk's book Rays from the Ashes from the year 1959.

August 6, 2020, marks the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing. By then, however, most hibakusha and many of the hibaku nisei will have died. Only a few kataribe will tell about their experiences on those two days and the time after. That is the reason why I have republished the sound recordings with the survivors that I made in Hiroshima in 1995 for the 50th anniversary now as a book. They are the testimonies of people who will soon no longer exist: the survivors of the atomic bombs.

Hardy Tasso, April 2020

Why Hiroshima?

U.S. Lieutenant General Leslie R. Groves was the military head of the development of the atomic bomb in the Manhattan Project, which was housed in the large-scale research facility, the National Laboratory, in Los Alamos near Santa Fe, New Mexico. As the project's chief military decision-maker, he explained why Hiroshima was to be the first target of the first atomic bomb:

"It is desirable that the first time it is an object of such a size that the damage is within its limits so that we can assess the violence of the bomb all the more accurately."

The Hiroshima nuclear bomb "Little Boy" 1)

Approach in 1945

At 8:07 local time, Hiroshima came into view. Navigator Captain Theodore J. Van Kirk had led the Enola Gay precisely to its goal.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, commander of the plane that flew the atomic bomb to Hiroshima, had named the B-29 Superfortress after his mother Enola Gay, and had the name painted in large letters on the left side of the nose of the plane.

The Enola Gay with Paul Tibbets in the cockpit 2)

Mission map for the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 3)

The Enola Gay flew at an altitude of 30,700 feet (about 9,000 meters), approaching from the southeast towards Hiroshima.

Bombardier Major Thomas Ferebee crawled into the acrylic glass observation dome at the front of the B-29 and looked down on the city through his bombsight. His destination was the Aioi Bridge over the Ota River; the bridge connected three banks and therefore looked like a "T."

10 miles before the bridge, Major Ferebee saw the bridge and adjusted the setting of his bombsight to compensate for the strength and direction of the wind; then, he connected it to the plane's autopilot.

60 seconds before the bomb was dropped, Ferebee pressed a switch that was supposed to release the bomb automatically. At 8:15, the bomb dropped 17 seconds later than planned. At that moment, the plane got four and a half tons lighter, the weight of the weapon. The top of the aircraft jumped up. Immediately after the drop, pilot Paul Tibbets went on the opposite course and steered the plane at a breakneck angle of 160 degrees down to the right, losing 1,700 feet (500 meters) in altitude and accelerating to top speed. Tibbets had to escape the expected shock wave of the bomb. After a drop of 43 seconds, the atomic bomb exploded at the previously set altitude of 1,890 feet (about 580 meters). However, as the Enola Gay was flying 500 to 1,000 feet too high, the headwind, which was stronger at higher altitudes, took the bomb 800 feet (240 meters) off its calculated course, so that it missed the Aioi Bridge and exploded over the clinic of Dr. Kaoru Shima.

Within the 43 seconds of the bomb's fall, Tibbets managed to move the Enola Gay 11.5 miles (almost 19 kilometers) away from the point of drop before the shock wave of the explosion caught up with the plane. The compressed air shook the B-29 violently, but without severely damaging it. Had Tibbets flown a less risky turn or crossed Hiroshima, the B-29 would probably have been destroyed.

A little later Captain Robert A. Lewis, the co-pilot of the Enola Gay, wrote in his log: "Oh, my God! What have we done?"

Just one day later, on August 7, 1945, The New York Times published in an article what co-pilot Lewis had reported when he looked back at the destroyed Hiroshima:

Even when the plane was moving in the opposite direction, the flames were still terrible. The urban area looked as if it had been torn to pieces. I've never seen anything like it—never seen anything like it. When we turned our plane to observe the result, the biggest explosion man has ever experienced was before our eyes. Nine tenths of the city were covered by a column of smoke that reached a height of more than six miles (10,000 meters) in less than three minutes. We were frozen by sight. By far, it exceeded all our expectations. Even though we had expected something terrible, what we saw made us feel as if we were warriors of the 25th century. Even after an hour, when we were still about 250 miles (400 kilometers) from our destination, the cloud increased in thickness. The column of smoke had reached a height of nine miles (15,000 meters), much higher than we were. The cloud kept changing its eerie colors until we lost sight of it.

On August 9, 1945, U.S. President Harry S. Truman gave a radio address to the American people:

The Japanese have learned what our atomic bomb is capable of. Japan can foresee what the atomic bomb may do in the future. The world has now learned that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima—on a military base. We chose this target because we wanted to avoid killing civilians as much as possible during our first attack. This attack is a warning of what is to come. If Japan does not surrender, bombs will be dropped on its war industry, and unfortunately, thousands of civilians will lose their lives. I strongly advise Japanese citizens to leave the industrial cities immediately and seek safety. I am aware of the tragic significance of the nuclear bomb; their development and use were not ordered lightly by this government. But we knew that our enemies were in the process of developing an atomic bomb, and we now know how close they had come to that goal. We knew what catastrophe would befall our nation and all peace-loving nations, all civilized countries if our enemies had first invented the bomb. We won the race for the atomic bomb against Germany. After we invented the bomb, we used it. We used it against those who attacked us at Pearl Harbor without warning. We used the bomb to end the agony of war and to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans. We will continue to use the bomb until we have completely destroyed Japan's ability to wage war. Only a Japanese surrender will stop us.

On the same day, the U.S. dropped the second atomic bomb: on Nagasaki.

The Enola Gay after returning from Hiroshima 4)

On August 14, 1945, the bombardier of the first bomb, Major Thomas Ferebee, was asked by John F. Moynahan, Public Relations Officer of the U.S. Air Force, about his experience during the flight. Ferebee replied, "My navigator has brought me correctly over the target. In my bombsight, I could clearly see Hiroshima. I disengaged the bomb and felt it leave the plane, it successfully hit the target. This meant a great deal to the Air Force, American science and industry."

However, Tibbets never expressed regret for his efforts. On the contrary, he always maintained that the use of the atomic bomb had saved lives because a U.S. invasion of Japan would have claimed many more victims on both sides. When asked if his actions incriminated him, he replied, "Hell, no!"

Sources:

John T. Correll. "Atomic Mission." Air Force Magazine, September 28, 2010, https://www.airforcemag.com/article/1010atomic/

Marc von Lüpke. "Reuelos nach dem Massensterben" Spiegel online August 4, 2015.

Sven Felix Kellerhoff: "So sollte die Atombombe auf Hiroshima fallen"Welt.de, April 28,2015.

Michael Schmid. "Hiroshima: Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit”, speech at the Opening oft he Exhibition "Hiroshima mahnt: Nie wieder Krieg!" in Gammertingen, November 9, 2005.

Yoshito Matsushige: As a Photographer, He Took the First Photos after the Explosion of Little Boy

During our interview, Yoshito Matsushige showed me some of the photos he took on August 6, 1945, after the explosion of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima and told me of the circumstances under which he had taken each of these photographs. In this book, I only show his pictures in which no dead or wounded persons are to be seen.

The so-called "T-bridge" in the center of the city was the target of the first atomic bomb 5)

Yoshito Matsushige, 1995

Shortly after midnight on August 6, there had been an air raid siren. Therefore, I spent the night at the newspaper office where I worked as a cameraman for the newspaper Chugoku Shimbun. I was also a member of the media group of the 5th Army Division. The newspaper office was only 900 meters away from the hypocenter. When the air raid alarm ended in the morning, I took my bicycle, and I went from the newspaper office home to the Midori district, seven kilometers (about four miles) away from the hypocenter. That saved my life.

After I had breakfast at home, I wanted to go back to work at the newspaper office. That's when the atomic bomb exploded. I thought it was a regular bomb. I took my wife by the hand, and we left the house. We huddled together in a field. But the area was pitch black because the road dust had been thrown into the air by the explosion. At the same time, radioactive ash fell from the sky. It was like a black fog.

When we were crouching in the field, I held my wife's hand. We could not see each other, but I felt the warmth of my wife's hand: she was alive.

When we later went home again, there was a big hole in one wall of our house, and the floor inside was full of sand. Under the rubble, I looked for my camera because I thought I should go to the office of the 5th Division now.

I came to the place where the city office and the western fire station were located one mile from the city center. The city was in flames. Because of the fire, I couldn't get closer to the center, so I went to the Miyuki Bridge to get to the center from there. But even that was not possible because of the fire.

I took my first photo at about 11 o'clock. I took it west of Miyuki Bridge, 1.4 miles, from the hypocenter. The photo shows a young mother desperately seeking help; she is holding her baby in her arms even though it is already dead. It didn't open its eyes. The mother shook the baby and yelled at him, "Open your eyes!" That was the first picture I took.

Shortly afterward, I saw another terrible scene. First, I wanted to take a picture, but when I looked through the viewfinder of the camera, the view was so hellish that I couldn't press the shutter button.

Mother with child 6)

Most of the people in the photo are students. Together with soldiers, they tore down houses so that the fire could not spread so quickly after a bombing raid. The students cleared away the rubble after soldiers had torn down the houses.

Wounded people 7)

On the morning of August 6, the sky was completely clear, with no clouds. Under this sky, the students were exposed to the heat beams of the atomic bomb. Their hair was burnt, their skin hung in tatters from their bodies. It was tough for me to press the shutter button. Still, I felt responsible for taking pictures for posterity: as a photographer for the newspaper and as a media member of the military office.

I took my second shot there. As I approached, I noticed that the faces of the students and soldiers were black and burned. When I took this second photo, I did not look through the camera viewfinder because my eyes were filled with tears.

After I took these two photos, I went home again. At two o'clock in the afternoon, when the fires had died down a little, I tried again to get to the newspaper building and the military office. This time I took the route across the university grounds. There I passed a swimming pool. In those days we collected water in all kinds of containers. When I had passed the swimming pool on August 5th, it had been filled with water. When I passed by there on August 6, there was no more water in it, but instead five or six dead bodies. I imagined that people had sought shelter from the fire and jumped into the pool. But the water had been brought to a boil by the heat of the bomb and evaporated. People had wanted to save their lives in the pool, but it was too late. They stayed in there and died.

I kept walking towards the center. Out of the rubble and the ruins of the flames of the house still blazed here and there. I reached the newspaper building. Everything in the building was burnt; only the steel framework of the building was still standing. I tried to get into the building, but it was covered knee-high with ashes and rubble; I could not get in. I then followed the trolley tracks to the center. Then I saw a burnt trolley. When I got closer, I saw people in it. When I looked even closer, I saw 15 people lying on top of each other, dead. That was 200 meters from the hypocenter.

The speed of the blast wave of the explosion was 440 meters per second: the pressure crushed chest cavities, causing people to die immediately. There were many fires in the city, even in the trolley. The people inside were all naked; their clothes must have been burned. I wanted to take a photo, but back then, pictures of dead people were not printed in newspapers. Although I walked through the city for three hours, I did not take any more pictures of people near the center. In those three hours in the burning town, I saw masses of dead people. Although it was very hot in the city, I don't remember my body feeling hot. I think my nerves were numb.

Later I saw the photo of another photographer. The heat of the explosion had burned the pattern of a kimono onto a woman’s skin.

At the entrance of Sumitomo Bank, I took another photo. In the morning, a woman had been sitting there. The heat of the explosion was 3,000 to 4,000 degrees Celsius. This high temperature can quickly vaporize a human body. The melting temperature of iron is 1,538 degrees Celsius; the heat on the ground was more than twice as high so that all living beings in the surrounding area had evaporated.

Shadow at the entrance to Sumitomo Bank 8)

I took another photo at the Miyuki Bridge, which is 2.3 kilometers away from the hypocenter. Here the bridge railings on the north side were bent by the explosion, and the railings on the other side had fallen. And this happened even though this bridge was the strongest bridge that existed in Hiroshima at that time. It was built of stone. Later I came to Motoyasu Bridge, which is the closest bridge to the hypocenter. Due to the explosion and the heat, the railings were bent there as well.

The heat from the bomb burned the shadow of the bridge’s railing into the asphalt 9)

A photo by another cameraman from the newspaper Chugoku Shimbun again shows a bridge, which was 760 yards (700 meters) away from the hypocenter. The tremendous heat had melted the asphalt pavement and burned the railing as a shadow onto the road. Today the photo is on exhibit at the Peace Memorial Museum. People found it seven years after the explosion.

Around 5:30pm, I took a picture of an injured policeman who was issuing certificates of the accident to people as if it was the most natural thing in the world.

On August 6, 7, and 8, many people died in Hiroshima. Many of the dead were burned and buried. But some of them were buried somewhere in Hiroshima. Even years later, construction workers kept finding human bones when building new houses.

A police officer issues a certificate 10)

I did not get injured or sick by the bomb, but I got tuberculosis due to malnutrition. I'm missing half a lung today. I'm lucky that I can still talk to people today.

Finally, I took a photo of the Torii gate of a Gokoku shrine directly below the hypocenter: that gate had survived the explosion.

Torii Gate of the Gokoku Shrine in Hiroshima, 1945 11)

On a map of Hiroshima, the area hit by the heat of the bomb is marked in red. The total area of the city at that time was 72.7 square kilometers. The burnt area took up 13.2 square kilometers. The area affected by the atomic bomb in one way or another was 30.3 square kilometers —almost half of the city. The number of dead in Hiroshima was 140,000. Another 3,677 people were missing. 30,524 were seriously injured. 48,606 were slightly injured. 118, 613 people were not injured. Before the bomb, the total population of Hiroshima had been 320,081.

The photo of the early mushroom cloud was taken by another photographer. He was five miles away from the hypocenter.

Mushroom cloud of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima 12)

One Billionth of a Moment

8:15. One billionth of a second. 580 meters above downtown Hiroshima, "Little Boy" explodes—that's what the inventors have named this atomic bomb. A wristwatch now stands still; it will be found later and exhibited in the Peace Museum. A woman evaporates from the Sumitomo bank, leaving only her shadow. Charred rice in a tin can. A "beautiful flash" of the colors red, yellow, blue, green, and orange outshines the city like a second sun. Radiation spreads invisibly. A tremendous heat causes bridge railings to melt and ignites wooden houses. An immense pressure chases myriad splinters of wood, glass, and bones through the city, shooting them into arms, legs, and heads. Within this split second, 100,000 people die. A black rain of ashes and radioactivity falls on the survivors.

Radiation

In the first seconds after the explosion, neutrons and gamma rays penetrate the air, houses, and people in the city center. They go through almost everything. High radiation doses break chromosomes in nerve cells, causing cell nuclei to swell, and making membranes impermeable. Nerve cells die within hours—people usually within the same day. There is no therapy.

Low doses of radiation destroy the mucous membranes of the stomach and intestines: nausea, vomiting, and severe diarrhea follow.

Even lower doses of radiation reduce the number of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets. People bleed from the mouth, from the nose, from other body orifices, inside the body from organs until they bleed to death. Large bloodstains grow under their skin.

Fireball

Still, it is quiet in this first time almost without time. In the next small moment, the air swallows the soft X-rays of several tens of millions of degrees