Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IVP Formatio

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

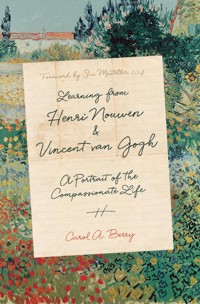

Carol Berry and her husband met and befriended Henri Nouwen when she sat in his course on compassion at Yale Divinity School in the 1970s. At the request of Henri Nouwen's literary estate, she has written this book, which includes unpublished material recorded from Nouwen's lectures. As an art educator, Berry is uniquely situated to develop Nouwen's work on Vincent van Gogh and to add her own research. She fills in background on the much misunderstood spiritual context of van Gogh's work, and reinterprets van Gogh's art (presented here in full color) in light of Nouwen's lectures. Berry also brings in her own experience in ministry, sharing how Nouwen and van Gogh, each in his own way, led her to the richness and beauty of the compassionate life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 204

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to my sonsAndris, Mathias, and Kristof.

Like Vincent and Henri, they seek to live by following their conscience, often going against the grain but always offering blessings of compassion

CONTENTS

Foreword

Sue Mosteller, CSJ

Spiritual yearning . . . has brought me calm,peace, prayer, compassion, and forgiveness—so I have received joy and freedom.

eading this book, my eyes welled with tears as I toured it like an art gallery of portraits and images portraying the spiritual yearnings in the lives of the author, Carol Berry, and her not-nearly-perfect but precious friends, Vincent van Gogh and Henri Nouwen. Tears also came when I was absorbed by the artists’ letters and stories that so vividly portrayed my own soul-felt yearnings and connected with the pain I encounter in life. Pouring over this perfectly subtitled book, A Portrait of the Compassionate Life, felt like walking through an art gallery. I was compelled to stop; step “into” each work of art; gaze; note the detail, color, darkness, and light; and allow my heart to feel how human anguish ever so gradually mutated into compassionate living. This, I strongly believe, is the only way to read this book!

As the author, Carol becomes the tour guide for readers who also spiritually yearn to grow in compassion. She is unique and the only person who could pen a book of such feeling and depth. During the past forty years, she has cared pastorally with her husband, Steve, for his parishioners in wealthy and poverty-stricken churches across the country.

In her efforts to be further inspired by her two friends, Carol has studied Vincent’s letters and, in the middle of the night, looked long and hard at Vincent’s paintings. With exceptional passion, she has thoughtfully confirmed her knowledge of, and friendship with, Henri Nouwen’s life story from friends and his more than forty books. Mother of three beloved sons, she is an accomplished artist and art instructor, having offered countless retreats and workshops on the lives and ministries of van Gogh and Nouwen. To meet Carol is to encounter the influence of her brother-artists in the flesh. I have known her for twenty-five years, and she is, for me, an example of mercy and compassion, a beloved sister who touches my life with beauty and love.

This is not a book about ideas or a theological treatise but a book of living portraits of people whose hearts, like ours, have been molded in a broken world by a wide range of experiences such as love, fear, hope, despair, pain, care, and yearnings for power or compassion. It is a true story, and one that invites us to identify painfully and hopefully with its subjects. Each portrait draws us into our own deepest heartfelt aspirations designed in the image of God for our living in an imperfect world.

The book you hold is more than a book. It is a revelation! Studying the portraits, examining the letters, and reading the stories, one enjoys the rare privilege of personally identifying with both the vulnerability and the power revealed in hearts where compassion was born from anguish. The artists become guides and shepherds, tracing the universal pathway to human tenderness and understanding.

Richard Wagemese’s spiritual yearnings, quoted above, eventually brought him calm, peace, prayer, compassion, and forgiveness, resulting in joy and freedom. I trust and believe that Carol and her friends bring comfort to the painful longings in our vulnerable hearts. May your tour of this unique gallery of transformation become a fruitful journey into your heart’s desires!

Introduction

EncounteringHenri and Vincent

e almost didn’t go to New Haven, Connecticut, in autumn 1976. My husband, Steve, was sitting at the kitchen table in our little parsonage in northern Vermont one late summer day that year when he opened the anticipated envelope from Yale Divinity School. The first sentence began, “We regret to inform you . . .” Without reading any further, he tossed the rejection letter into the empty fruit bowl.

While working toward his undergraduate degree, Steve had served as a licensed student pastor for three years in two rural parishes in northern Vermont. At the insistent encouragement of a retired clergy friend, a Yale alumnus, Steve had applied to Yale Divinity School. It was the only application he sent. Expecting to move by the fall after his graduation from Johnson State College, he informed the two parishes of our intention to leave. When the letter arrived, we had just a few more weeks of parish ministry left with no plan B. And on top of that, I was entering my ninth month of pregnancy with our first child.

A week went by before Steve finally did retrieve that missive from the fruit bowl and read it through to the end. And there it was—the chance that we had almost missed. The concluding paragraph stated that Steve should inform the Yale Admittance Committee by return mail if anything in his application had been overlooked or misunderstood. Steve immediately contacted Yale Divinity School again. This time he submitted examples of sermons he had preached, including a detailed account of our three years’ parish experience. For good measure he added a list of all the books he had read while preparing his sermons. Within another week and a half Steve received an acceptance letter. A few days later he was on his way south with a U-Haul, transporting our few belongings to student housing on the Yale Divinity School campus in New Haven.

Life during the initial months on campus couldn’t have been more different from our parish life with the rural folks up north. For me the days were filled with the wonders and challenges of caring for our baby boy, Andris. Meanwhile, Steve couldn’t seem to find his bearings in the competitive atmosphere of academia. Further, he felt that after his experience of a hands-on ministry, the academic setting seemed artificial and not in touch with reality. He could barely open his books and was falling drastically behind in his course work. He began questioning whether he had made the right choice to enroll in divinity school—until he met Henri Nouwen, who was at that time a professor at the Yale Divinity School.

My first meeting with Henri Nouwen is still very vivid in my mind. Stepping into the Yale Divinity School bookstore one day, my ears immediately picked up an unmistakably Dutch accent spoken by someone on the other side of the bookshelves. Following the sound, I saw a man dressed in a well-worn, baggy, moth-eaten sweater with a woolen scarf around his neck. His hair was disheveled. He had thick glasses perched on the tip of his nose and was carrying an armload of books. He looked like the typical student, somewhat older than the rest maybe, but definitely one of those studious types who neglect everything else except their studies. Eager to meet a fellow European (I grew up in Holland and Switzerland), I approached him and asked, Studeert U hier (Do you study here)?

Without letting me know that I just made a faux pas, he simply said, Nee, ik geef hier les (No, I give lessons here).

Thankfully, this short dialogue had been spoken in a language no one else likely understood, so my mistaking one of Yale Divinity School’s most distinguished professors for a mere student had no witnesses. Henri just looked at me kindly with those big eyes of his, and our friendship began.

COMPASSION AND VAN GOGH

During the second semester Steve enrolled in Henri’s course called “Compassion”—a practical, nontheoretical class meant to prepare seminary students for the actual life of parish ministry. Henri based the core of his teachings in this course on the Scripture passage from Paul’s letter to the church at Philippi: “There must be no competition among you, no conceit; . . . always consider the other person to be better than yourself” (Philippians 2:3 JB). As Henri and the students deliberated on Paul’s words, Steve realized that this Scripture contextualized many of the experiences he had had during the three years of parish life. Henri helped Steve become aware that he was actually far ahead of his colleagues in this particular class. Steeped in a practical ministry, Steve had witnessed compassionate living firsthand, exemplified in countless interactions within the lives of our rural parishioners.

At Yale Divinity School, the “Compassion” course remained the most meaningful class Steve attended. In Steve’s words, “It turned out to be the singularly most important class that I ever took in all my years of schooling either before Yale Divinity School or after.” Thanks to Henri, Steve felt his call to ministry affirmed. For the next two years Henri became Steve’s mentor and offered him one of his teaching-assistant positions.

Today, Henri is primarily known as an author, but in the mid-1970s Henri’s focus was on preparing seminarians for the Christian ministry. Henri the author was first Henri the pastor and teacher. During his professorship at Yale Divinity School, a focal theme of his teaching was on how to reach out compassionately in settings of parish ministries wherever these parishes would be. There was a need for more compassion in the country. We had just ended the Vietnam War, racial tensions were high, and so was the nuclear threat. There was a great deal of violence on many levels of society. What is compassion? Henri asked. Compassion, he said, was best understood by a desire to serve and by entering into the suffering of another. To be compassionate, one had to become present to the other. One had to be willing to walk with, sit with, cry with, and bind the wounds of the other; being compassionate means literally to suffer with.

Steve discovered that Henri was going to teach a similar class the following semester with limited enrollment, this time focusing on the artist Vincent van Gogh as a case study for compassionate living. He immediately suggested that I audit the class. Loving art and being an aspiring artist, I didn’t need to be coerced. I, like Steve, entered into an experience that would eventually guide me in my life’s vocation.

Henri introduced his class “The Compassion of Vincent van Gogh” with these words:

Here we are—people who want to prepare for the ministry. What do we want to do as ministers? Well, one thing is sure: We want to give strength to people in their daily life struggles. Many people have done this, and we often reflect on their lives for inspiration. I should like to introduce to you a man you have often heard of but not as a giver of strength, not as a minister. . . . It is the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh.1

Henri’s aim was to create a space and time where a true encounter with Vincent could take place.

Those of us who were familiar with Vincent van Gogh knew him primarily as an eccentric and deeply troubled artist who ended his own life at the age of thirty-seven. According to popular understanding, Vincent was first of all a social outcast. He was also a man who drank alcohol excessively at times. He visited brothels. I wasn’t the only one asking myself, how could someone with this character become a case study in a class at a theological seminary? How could future pastors learn about living a compassionate life from a man who was disagreeable, prone to bouts of melancholy, and, some of us knew, had chosen to live with a prostitute? How could someone with such apparently great flaws teach us about anything? We all were curious. How did Henri come to hold this artist in such high esteem? How would Henri hope to make us understand Vincent’s broken life and use this life to teach us about compassion? What made Henri say that the longer he lived and tried to make sense out of his own struggles, the more he found in Vincent a kindred spirit? For, Henri said, when he had felt lonely, Vincent had become his companion, someone he could identify with. Henri told us that Vincent had touched him deeply from within just as Thomas Merton had—by putting him in touch with parts of himself that he hadn’t been able to reach. But, really, we wondered, how could Henri reach the conclusion that Vincent van Gogh was his saint?

MISUNDERSTANDING VAN GOGH

There is much written on Vincent van Gogh from the point of view of art history and psychoanalysis but very little about his spirituality. Henri, who had studied psychology at the Menninger Clinic, disagreed with what he basically saw as caricatures of van Gogh. The experts in the art world, Henri noted, portrayed Vincent as a psychologically disturbed, mentally imbalanced, and crazy artist. Henri asked us to consider why, if Vincent was so crazy, were people from all walks of life drawn to him? Was he really crazy? What were people neglecting to understand? Were they willfully ignoring the realities that Vincent was obsessed with—such as care for the poor? Most people did, for it took a more in-depth study of Vincent’s life to discover those realities.

Henri had decided to devote much time to getting a closer look at this artist when he visited his native Holland. While in Amsterdam, he entered the newly opened Van Gogh Museum (which had opened in 1973). This museum houses the largest collection of Vincent van Gogh’s art in the world, arranged in chronological order. Here Henri could walk along a visual time line of Vincent’s ten years of artistic life displayed on the walls of the museum. This experience of viewing Vincent’s work almost in its entirety is only possible in the Van Gogh Museum, and this was crucial in discovering that Vincent’s mission was to use art as an expressive language.

The art critic Maurice Beaubourg is quoted as having written, “One shouldn’t look at just one painting by Mr. Vincent van Gogh, one has to see them all in order to understand.”2 Henri looked at Vincent’s early sketches depicting the rural and urban poor and the somber interiors of peasant cottages in Holland. He then continued on to the sun-drenched landscapes created in the south of France. He became increasingly aware of the artist’s intention to have his art give voice to his feelings rather than to reproduce only what he saw. The sequential course of Vincent’s work elucidated the artist’s attempts to develop an art that spoke, that communicated, and that would touch people.

During that museum visit, Henri also had an encounter with Vincent’s nephew, Dr. Vincent van Gogh, who had been instrumental in the establishment of the Van Gogh Museum. Henri asked him why so many people flocked daily by the thousands to look at his uncle’s paintings. What was it about Vincent that touched a chord that resonated deeply within us? Henri related Dr. van Gogh’s answer: “Because people feel comforted and consoled. Vincent was able to crawl under the skin of nature and people and find there something truthful, something beautiful, something joyful, and something worth seeing. He was able to draw out the inner secret of what he saw.”3 This response affirmed Henri’s own sense that Vincent’s art did not merely satisfy aesthetic demands but sought to connect with people in a profound way.

The words of Dr. van Gogh stayed with Henri as he began a fascinating and soul-enriching journey into Vincent’s life and art. Henri developed a deep bond with Vincent after reading the artist’s extensive and very private correspondence, mostly to his younger brother Theo. These letters, as we would come to discover, form a most unique document, not only in the history of art but as a profound literary testament of the life of a wounded healer. Vincent had hoped to comfort through his art, but his letters have that effect too. We would come to understand why Henri identified with Vincent. They both shared the desire to reach suffering people with messages of reassurance and hope. And just like Vincent, Henri hoped to touch lives through his creative work. Just as Henri strove to live the faith of Jesus, so too did Vincent.

What left a deep impression on Henri was that, despite Vincent’s many rejections and failures, Vincent retained this tremendous inner drive and desire to comfort and touch people through a language that could be universally understood. In our class Henri explained, “Vincent offers hope because he looks very closely at people and their world and discovers something worth seeing.”4 Vincent wanted to offer comfort because he had been willing to crawl under the skins of others and discovered that he shared the same human condition. Henri recognized that Vincent was an artist with a mission, as well as a prophet and a mystic. Vincent was above all a compassionate man. This book is about Henri’s insights into Vincent’s life from the course “The Compassion of Vincent van Gogh.”

AN ONGOING FRIENDSHIP

My last encounter with Henri at the divinity school happened in a very different setting from my initial meeting. I was in the hospital with my day-old second son, Mathias. Still exhausted after the birth and happily settling into nursing my little son for the first time, I was not expecting any visitors. But then, quite abruptly, the door to my room swung open and there was Henri. No time to put on a robe or comb my hair. Nothing deterred Henri from what he had come to do—to bless our little child. So with his warm, large hand, Henri reached over, placed it on Mathias’s head and blessed him. In the years to come, our encounters with Henri, mostly by letter, were just as natural, as spontaneous, and as moving. We always connected through ordinary moments and situations, which in turn became blessings every time.

Two weeks after Henri’s visit to the hospital, Steve, Andris, Mathias, and I left for St. Louis, Missouri, where Steve’s first job after graduation was taking us. Steve had told Henri that we wanted to go back to serve a little rural church in Vermont. Henri urged Steve to seek an inner-city ministry instead. So that is what we did and where we went to resume our ministry after the three years of student life. The inner-city, biracial church in St. Louis was a far cry from our first two rural parishes in northern Vermont! There, our third son, Kristof, would be born. After three years there, we continued our parish ministry in large inner cities for twenty more years, first in New York City, then in Los Angeles. In 2001 we came full circle by returning to Vermont to serve in a village church.

During the years of our urban ministries, we were honored and happy to be able to welcome Henri several times into our home as our friend and workshop leader. We also traveled to visit Henri at the L’Arche Daybreak community in Toronto, where Henri served as spiritual director after leaving academia behind. At L’Arche we perceived Henri’s love for the core members and witnessed their love for him. He was at L’Arche to pastor these men and women with mental and physical infirmities, but he was also an active participant in the day-to-day life of caretaking. Henri continued to inspire us through his compassionate outreach, his guidance, and his wisdom, much of which reached us through his many books. Then in l996, on a Sunday after our church service in our Los Angeles parish, we were shocked and saddened to receive the news of Henri’s sudden death. Steve flew to Canada and was among more than a thousand people who joined together in a memorable and profoundly beautiful celebration of Henri’s life and ministry. Steve was overwhelmed by the great outpouring of love and gratitude that filled the Cathedral of Transfiguration in Markham near Toronto. The many core members of the L’Arche community who had been touched and blessed by his life encircled Henri’s simple pine casket. It was covered by an abundance of glorious sunflowers paying homage to Henri but also alluding to his bond with the artist Vincent van Gogh, who had affected him so deeply.

THE BEGINNINGS OF THIS BOOK

A few years after Henri’s death I was contacted by our dear friend Sister Sue Mosteller, Henri’s literary executor and spiritual director, because she knew I had attended his class “The Compassion of Vincent van Gogh.” Since he had never published a book based on his lectures, Sue hoped that I would do something with all the course material she had sent to me with the instructions: “Write the book!”

Reading through Henri’s notes reawakened in me the excitement and passion I had felt years before sitting in his classroom. For the last twenty years I have publicly presented Henri’s and Vincent’s words and Vincent’s paintings in numerous workshops and lectures, focusing on Henri’s message of compassion as exemplified in the life of his saint.

Henri revealed to us in his course that when one reads Vincent’s letters and contemplates his paintings, three aspects of compassion come into focus. Henri said, “When we say blessed are the compassionate, we do so because (1) the compassionate manifest their human solidarity by crying out with those who suffer, (2) they console by feeling deeply the wounds of life, and (3) they offer comfort by pointing beyond the human pains to glimpses of strength and hope.”5 These three stages—the progression from solidarity to consolation to comfort—which Henri felt contributed most significantly to living compassionately, define the structure of this book.

In the pages that follow, Henri and Vincent will speak with their own words in the first two chapters of each part. (Any uncited Nouwen quotes are from the course lectures.) Henri’s and Vincent’s ministries and guidance have made me more conscious of the ways Steve’s and my lives have been touched by grace and compassion. My own stories and reflections form the third chapter in each part. They are taken from ordinary moments of our parish life together, which have again and again pointed beyond the human pains to glimpses of strength and hope.

Henri told us at the beginning of his course on compassion that we would attempt to reach another level of discourse about Vincent van Gogh. We knew how to talk about art and psychology; we now would have to find ways to speak about Vincent’s ministry. Henri felt that by studying one man’s life and work, we could touch on many subjects. Such an intimate involvement with Vincent would also help us grow and learn more about ourselves. We had to make space within us for his story to connect with our stories. My hope is that my encounters with Henri and Vincent and with the people from our different parishes will enable you to recognize more fully the moments when you too were touched by grace and compassion.

Part One

Solidarity

The compassionate manifest theirhuman solidarity by crying outwith those who suffer.

I believe that, after all, I havedone nothing or shall never do anythingthat would have had me lose or make melose the right to feel myself a humanbeing among human beings.