Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

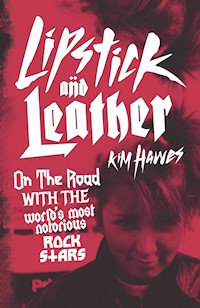

What do Motörhead, Black Sabbath, Elvis Costello, Rush and Chumbawamba have in common? Kim Hawes, pioneering female tour manager. Kim Hawes spent years sleeping underneath Lemmy from Motorhead… on a tour bus. She feuded with the members of Black Sabbath, tripped mushrooms on stage with Hawkwind, faced down the Hells Angels and escalated band prank wars. She threw Madonna off her stage, turned down an invite from Nelson Mandela, and dealt with the aftermath of Chumbawamba drenching John Prescott. Through hard work, hard drinking and hard times, Kim refused to conform to others' expectations. She hurled a TV through the glass ceiling of the male-dominated music industry, blazing a trail for young women today. She carved out a place for women in a largely man's world, taking no crap and no prisoners while getting results other tour managers only dreamed of. This memoir of the nitty gritty of life on the road – the fights, the dares, the smashed hotel rooms and even an encounter with a Soviet submarine – is full of fresh stories about the famous names you think you know. Lipstick and Leather: On the road with the world's most notorious rock stars is a must read for anyone who wants a fresh insight into life on the road.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 475

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2023

Sandstone Press LtdPO Box 41Muir of OrdIV6 7YXScotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Kim Hawes 2023

Editor: K.A. Farrell

Shot of Elvis Costello, taken at Preston Guild Hall 1979

© Elvis Costello 1979

All other images © Kim Hawes

The moral right of Kim Hawes to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-914518-00-3

ISBNe: 978-1-914518-01-0

Jacket design by Ryder Design

Ebook compilation by Iolaire, Newtonmore

Lemmy, if you can see this, you were right. It is in my blood.

List of Illustrations

Elvis Costello and the Attractions back when I first saw them liveMy never-husband, Steve NieveWaiting to head out on my first European tourJune posing by a tour busMy very first branded workwear, from the 1979 Rush tourMe with Lemmy outside Real Madrid’s stadiumPhil Campbell, Lemmy and Wurzel backstageMotorhead’s Bomber stage – spot the wings behind the lightsTaking my place on the tour busThe itinerary for Motorhead’s 1987 tourAt a bar somewhere in Germany, letting off steam during a Motorhead tour. My second husband Paul and I are furthest left, and you can just see Wurzel from behind his guitar tech Mike’s middle finger!Drinking from morning though to dark in Nice, 1987Paul with Lemmy – looks like a late nightWurzel, the most cheerful member of the band, checking his cameraPhil Campbell at soundcheckMaking the most of a day off in Athens, late 80sBlack Sabbath onstage at the LA Coliseum, early 80sPasses and itinerary from the Heaven & Hell tour, 1982Me with Girlschool – at a gig that went ahead! Late 80sConcrete Blonde, 1993: the night Johnette made us wear chicken heads! L-R: James Mankey, Johnette Napolitano and Harry RushakoffChicken-me with Holly Beth Vincent, who was supporting Concrete Blonde’s tourFrantically redoing the stage after a last-minute change by JohnetteBitches on wheels and other Concrete Blonde tour infoHard at work in one of the many hotel business centres in the US I used as an office over the yearsInfo booklet for Roskilde 2000, where fans were trampled to death. Chumbawamba were supposed to play, but didn’t out of respectMerch for ‘The King’ – Elvis impersonator James BrownMe and Mum

Contents

Introduction

List of Illustrations

Getting Out

Learning the Ropes

Driven to Distraction

We Are Motörhead

Being Badass in Brazil

The Band is With Me

Birthdays and Big Bashes

America

Toilet Tale

Violence, Ultra and Casual

When the Shit Hits the Fan, It Splatters

Get Off of My Stage

Bands Behaving Badly

Bringing Up Baby

Living the Dream

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Introduction

WHEN I WAS SIXTEEN, I WAS IN SCHOOL and working part-time on my grandparents’ market stalls in a commuter town outside Preston. Breaking into the music industry seemed so unlikely that I didn’t even dream about it.

When I was nineteen, I danced onstage with Hawkwind dressed in tinfoil and gaffer tape while tripping on magic mushrooms.

I can’t play an instrument, sing or read a note of music.

I was offered my first job because I was a brunette.

And for ten years of my career, I slept under Lemmy.

A few years ago, when a group of students taking a tour management course were told that a tour manager called Kim was coming to speak to them, they were asked to write down what they expected Kim to be like.

‘A bald shaven-headed man,’ was one answer.

‘A guy with thick heavy boots, rough, with a lot of tattoos – on his head, his arms.’

‘A very butch female.’

It’s funny to me that even now, in the twenty-first century, people assume I’ll be a man because of my name and work. Still, I always loved my name and the assumptions it led to. Whatever image it might have suggested to the contrary, I’m a woman who wore designer shoes rather than steel toe-caps, had freshly painted nail varnish instead of tattoos and carried a Tiffany pen instead of a spanner in my back pocket.

I was one of the first women in the industry ever to manage tours and I loved playing with expectations. The students’ suggestions show how the stereotypical image of the tour manager remains unchanged even now, more than thirty years on. But I always did dance to the beat of my own drum.

I got into the music industry for the love of it, the way most of us do.

The first gig I ever went to was David Bowie playing Preston Guild Hall. A neighbour took me and a few friends. After the show, as we were walking back to the car, our ears ringing, we found ourselves in the private parking area. David Bowie’s limousine was waiting there – and there, having just appeared from a stage door, was David Bowie, making his way over to it.

I couldn’t believe it.

‘Hello,’ I said.

‘Hello,’ he replied. Then he got in his car and was driven away.

To this day I can still remember the almost irresistible impulse to grab the door handle, open it and jump in. I had no idea that I’d meet him again one day and that it would be Lemmy making the introductions. Back then, I’d never even heard of Lemmy.

Once I was seventeen and able to drive, I used to go and see bands play at Lancaster University. I remember hearing The Jam there. The hall was so packed that we couldn’t get anywhere near the stage. Neither my friend nor I were tall, so we couldn’t even see it and ended up sitting on the floor, thinking what a waste of an evening it had been. We’d decided to leave when one of the crew, seeing us looking dejected and heading for the doors, asked if we’d like to meet the band.

‘Sure,’ we said.

My first look behind the scenes was in the dressing room. It was just a bland-looking room but a room full of enough alcohol to be the envy of many a good bar. And there were The Jam, drinking and relaxing.

It was an awesome feeling, one of being luckier and more privileged than my fellow attendees. We had all bought a ticket, but mine came with the jackpot of meeting the band, getting their autographs and even getting a piece of merchandise free – a tie.

One hit and I was hooked.

I should clarify here that not only did I sleep under Lemmy, I slept under all the guys in Motörhead, along with I don’t know how many other rock acts both male and female. And when I say I slept under them, I mean on the bunk bed beneath theirs when we were sharing a tour bus.

In my decades-long career I worked with – and often slept under – bands like Elvis Costello and the Attractions, Hawkwind, Rush, Concrete Blonde and Black Sabbath. Working the festival circuit, I was lucky enough to meet Iggy Pop, Mick Jagger and Blondie. I worked for Michael Jackson and I threw Madonna off my band’s stage.

It was one hell of a ride.

This all started, it’s worth pointing out, in the 1970s when everyone was brought up with Ian Dury and ‘Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll’. A question I imagine will occur to more than one reader, then, is: Did I? And who with? Though I hate to disappoint, the answer is ‘No’. I was married twice during my time on the road but neither of them was famous or in a band.

I’m not saying I was an angel though. Everyone on the road partied hard and there are plenty of stories of drugs and rock ’n’ roll debauchery in these pages. After all, the reason I always chose the bottom bunk was because I could crawl into it if I wasn’t in a fit state to do any climbing or clambering. The only disadvantage was the odour of the footwear invariably left just a few feet from my head, which I combated by spraying the curtain with Chanel No. 5.

How, then, did it happen that I, unmusical as I was, as unlike the stereotypes as I was, ended up spending the greatest part of my life touring with some of the biggest and most notorious rock bands in music history?

Luck was part of it. The other part was wanting more from life than what seemed to be my lot growing up in the rural north of England. When an opportunity came my way to go touring with a band, I saw a chance to break out and live outside the ordinary, see the world and have a good time. To escape.

I don’t pretend that my achievements were all down to me, and in these pages I gratefully acknowledge the many people who helped me get where I did. But I’m not so diffident as to make out that grit and graft and refusal to conform to expectations didn’t have a lot to do with it. I was a woman in a man’s world, and for all the times that caused me problems, there were just as many where I managed to turn things to my advantage.

In all the years of working with some of rock ’n’ roll’s brashest and brightest stars, I never ran, never shouted, never gave in and never gave up. It would have been easy, sometimes far easier, to give up and walk away, but I persisted. And in the end, I became the woman – and tour manager – I wanted to be.

CHAPTER 1

Getting Out

THE BACKING BAND FOR ELVIS COSTELLO was called the Attractions, and the one who held the greatest for me was the keyboardist, Steve Nieve. It was a joke – sort of – with my friend Jackie that one day I would marry him, while she would marry Elvis Costello himself.

It was Wednesday 17th January 1979 and we were in Preston to see the band play the Guild Hall as part of the UK leg of a tour extending across North America, Europe, Japan and Australia. Before the show, over a couple of rum and blacks at the Stanley Arms, Jackie and I made a bet to see who would be able to wangle their way backstage and meet the band. Now I think about it, I never got my winnings. In fact, by the end of the night, when I met her at the bus station to catch the last bus to Hesketh Bank, I’d clean forgotten about them. Though I went home with little hope for my marriage to Steve Nieve, I would be seeing him play with the band again. And soon after that, I would be joining them all on tour.

The groundwork was laid the week before Christmas 1977. I was staying with a family in Ohio on a school exchange, aged seventeen. The father of the family was a doctor working for NASA. I had watched the Apollo 11 moon landing on television almost a decade before and it had, of course, made a significant impression on me. I had a sense of being alive at a time when pivotal things were happening, and I didn’t want to miss out. Across the dinner table from this man who was a part of that other world, I felt the nearness of opportunity.

I grew up in a small village called Hesketh Bank, originally a farming village which by the early 1970s was becoming popular with commuters. Apart from the local youth club, there was nothing for us teenagers to do, so I started going to concerts. This exchange trip showed me that not only was a life working a shop job (as recommended by my career advisor) something I had nointerest in whatsoever, but that there really were other lives I might lead.

Later that evening, Elvis Costello was due to make his first appearance on Saturday Night Live after the Sex Pistols, who were originally scheduled to perform, had been waylaid by visa troubles. My exchange family was aware of my punk tastes and my liking for Elvis Costello, and obligingly gathered round the television to watch the show.

A few seconds into ‘Less than Zero’, Costello turned away from the microphone and waved his arms at the band saying ‘Stop! Stop!’ The band stopped. Turning back to the camera, he said, ‘I’m sorry ladies and gentlemen, there’s no reason to do this song here,’ and told the band to play ‘Radio, Radio’. They did, and were banned from the show as a result. At the time, failing to register the provocative nature of the stunt – a swipe at corporate control of rock ’n’ roll consumption – I was unaware that I had witnessed a moment of music television history.

At the end of my exchange period, I returned to Hesketh Bank and finished school. I did a modelling course but at five foot five I was told I was too short to pursue a career as a model. I ended up working three days a week on my grandparents’ stalls in Blackburn market. My grandmother sold handbags and luggage, while my grandfather was a market gardener. I was also training as a swimming instructor at Edge Hill College (now Edge Hill University) in Ormskirk.

All the while, I was waiting for something to happen.

When Jackie and I heard about Elvis Costello and the Attractions coming to Preston to play the Guild Hall, we didn’t hesitate to buy tickets. That Wednesday evening, the two of us plus a few other friends left the stuffy warmth of the smoke-filled pub and briskly walked the short way to the Hall, queued with the other red-cheeked fans, showed our tickets and went through to the auditorium. With money and pride at stake on our bet to meet the band, the two of us decided not to waste the time before the start of the show, our other friends egging us on.

We were both quite confident, Jackie perhaps more so than me. We had seen other bands in the past including The Stranglers, The Jam, Ian Dury, the Boomtown Rats and Siouxsie and the Banshees, and had got to know the DJ Andy Dunkley who toured with a number of rock ’n’ roll and punk bands. If we could meet Paul Weller without effort, think what we might achieve with a little contrivance.

We hitched up our Fiorucci jeans and split.

Walking round to the side of the stage, I approached the man who was guarding the stage door, somewhere behind which the band would be preparing for the show.

‘Can I help you?’ he said, sounding doubtful.

‘I hope so,’ I said. ‘I was with the band when they did Saturday Night Live in New York.’

The man’s eyebrows went up. ‘You were?’

‘Mm-hm,’ I nodded, hoping my face wouldn’t betray that this was, for all the communion of television, a complete and utter lie.

‘All right,’ he said at last. ‘Come back after the show, then. I’ll be right here.’

My heart did a little dance. ‘Thanks very much.’ I went off and found my seat.

When Jackie reappeared, I asked if she’d got anywhere. She shook her head. Me? Not yet, I told her.

Despite being giddy with anticipation, I remember the show well. John Cooper Clarke stalked the stage and Richard Hell and the Voidoids played a livening set before Elvis Costello and the Attractions finally appeared. Despite the criticism they had received for some lacklustre performances and a punishing tour schedule, they played a great gig. There was no sign of fatigue or false feeling that night.

When the show had finished, I told Jackie I’d meet her and the others at the bus station and made my way over to the side of the stage, looking for the man I had spoken to earlier. Not seeing him, I hung around the stage door, hoping someone would appear. I’d been standing there a while when the door opened and a bearded man who looked as if he was in his late twenties stepped out. Seeing me, he beckoned me over.

‘Come with me,’ he said. ‘I’ve told them you’re here.’ I followed him through the door and down a corridor. His name was Mike Smith, a promoter’s agent for Straight Music, run by John Curd. At that time, John was the biggest promoter in the country and I was fortunate enough to have him as a mentor when I entered the touring business later in life.

Then, though, Mike was asking me, ‘Enjoy the show?’ as he strode down the backstage corridor.

Struggling to keep up with him, I said I had, very much.

‘You’re from Preston?’

Not far from, I said, doubting he’d have heard of Hesketh Bank.

‘Long way from New York,’ he said.

I laughed.

When we got to the green room, Mike was told that the band had left for the hotel near the bus station, which is now a Holiday Inn. Mike asked if I would like to go over for a drink. My heart did another dance and, affecting cool, I said, ‘Sure.’ I looked at my watch and saw that I had about half an hour before I had to catch my bus. We went over to the hotel where Mike said they would be in the bar.

We walked through the lobby and up a flight of steps, and there they were, sitting round a table, nursing drinks. I followed Mike to the table and we sat. There was Elvis Costello, Bruce Thomas, the bassist, and Pete Thomas, the drummer.

And there was Steve Nieve . . .

‘Hello,’ he said.

I just about managed to say, ‘Hi.’

A silence ensued. Mike looked between them and me, evidently expecting a heartier reacquaintance. There was no chance of my saying anything more.

Mike shifted in his seat. When it was clear that not a flicker of recognition had passed across the faces of any of the band, Mike said, ‘Excuse us a minute,’ and signalled for me to follow him.

We left the bar.

‘So you know the band from Saturday Night Live?’

Not knowing what to say for myself, I said nothing.

‘Because I’d say, judging from their reaction just now, either they’re collectively amnesiac or that was a fucking porky.’

I waited to see what he would do.

To my surprise, he laughed. ‘That’s the first time anyone’s got one over on me.’

I smiled, relieved. I told him that I had seen the Saturday Night Live performance, only not in the studio but on the television set in a living room in Ohio. He asked me would I like to stay the night at the hotel. Being naïve, it was only later that I understood this to mean would I like to stay the night with him?

I told him no thanks, I had to get the bus home, and apologised for my economy with the truth. Before I left, he took my phone number and said he would get me a backstage pass to the Oldham gig the following Tuesday. I thanked him again, we said goodbye and I left.

I went to the Oldham gig where I received the pass Mike had promised, which I flaunted when I got home, high from my brush with the rock ’n’ roll life.

I hadn’t realised that Mike had expected to see me after the show. The next day I got a phone call from him. He asked if I would like to join the Elvis Costello tour for the last few gigs.

I had to ask him to repeat himself before it sank in. My mind was absolutely blown. Would I? Of course – absolutely – yes!

I blurted out a bunch of nonsense by way of thanks, to Mike’s amusement. He said he would call the following day, and after the phone call ended I was all but dancing in my living room.

The first person I told was my mum, who worked as a maths teacher at the local high school. Though I wouldn’t have said so at the time, she had a much better idea than I did of what I – still a girl, not a woman, far from worldly or wise – would be letting myself in for if I were to join the tour. She knew, though, what I wanted to do, and that if she said no, she would have found my bedroom empty one morning, the window open and curtains blowing.

Before she said yes, however, she asked to speak to Mike when he called and asked him for the names, addresses and telephone numbers of all the hotels we would be stopping at. She then called each of the hotels and booked me my own room, so that when I arrived each night I wouldn’t find myself having to share with anyone, including Mike – a possibility which, again, hadn’t occurred to me.

Thank goodness for my mum!

At Preston railway station I bought a single ticket to Bristol. I don’t remember being afraid. The purpose of fear, I think, is to influence your decisions, and my mind was already made up. There was no chance I was going to change it.

I’m sure my thoughts extended only as far as the rest of the tour – less than a week. I didn’t know where, if anywhere, it might lead. I certainly didn’t imagine it would lead where it did. All I knew was that I was going on tour with Elvis Costello and the Attractions. How many girls my age could say that?

It was about half eight in the evening when the train pulled in to Bristol Temple Meads. I found my way to the hotel, checked in, took my bags up to my room and went down to the bar to find Mike was there. He told me it had been a day off for the band, and asked how the journey down had been.

‘Fine,’ I said, and thanked him again for inviting me to join the tour. We had a couple of drinks, then Mike said, ‘Come on, better get to bed.’

Bed? It was a bit early. I was buzzing with excitement and alcohol. But I finished my drink and followed him to the lift anyway. We got in and he pressed a button. I pressed another.

‘What are you doing?’

‘I’m going to my room,’ I said. ‘I’m going to bed.’

‘What do you mean, your room?’

‘I’ve booked my own room. I’ll see you at the venue tomorrow.’

I got off on my floor. Having been granted the privilege of joining the tour, I was determined I wouldn’t be a nuisance and was pleased to have shown that I wouldn’t need any mothering.

I still hadn’t realised that Mike’s intentions could hardly be described as motherly.

The next morning I found the venue, the Locarno Ballroom. It was part of the Mecca entertainment complex called the New Bristol Centre on Frogmore Street, since converted into student accommodation. Mike wasn’t speaking to me and I didn’t know why. But nobody else was speaking to me either.

It occurred to me that nobody knew what I was doing there. Neither, I realised, did I. How was I going to occupy myself over the coming days? I sat down on a flight case and watched the crew unpacking equipment, setting the stage, testing levels. After a while I decided to go for a walk. I wandered around the venue, ventured outside and returned about half past five, by which time people were bustling about, hurrying to get everything ready before the doors opened.

Someone asked me if I had seen Lynda. I said I hadn’t, but then I had no idea who Lynda was. It was evident from the snatches of conversation I overheard that she was the cause of some concern. I heard someone say she’d been poisoned. Not sure that I’d heard right, I looked around, appalled at the thought of a poisoner in our midst. Had someone called an ambulance? Would she live?

She was most certainly alive when she whirled into the foyer a short while later, clutching her arm and expressing in no uncertain terms that she was in no state to sell T-shirts – just look at her fucking arm! Looking over, I saw the veins in her arm had turned a distinctly blackish hue.

‘Christ,’ someone said, ‘get her to the hospital.’

‘What happened?’ I asked a fraught-looking man who was shaking his head.

‘God knows.’ Then he looked at me. ‘Can you sell T-shirts?’

The question caught me off guard. A woman was being taken to the hospital and this man seemed completely unconcerned.

‘I . . .’

‘Yes or no?’ he said impatiently.

I tried to shake off the strangeness of the place and think. Could I sell T-shirts? I supposed so. I’d sold bags and flowers with my grandparents on Blackburn market. How different could this be?

‘You can sell T-shirts,’ he said, then took me over to the merchandise stall where he showed me the stock and told me how to keep the money. Having something to do, something almost familiar, soothed me and I found myself getting into the swing of it quite easily. So that night, and on the following nights in Southampton and London, I sold T-shirts for the band.

When the tour finished, I thanked Mike again, said goodbye and went home. It had been a brief but unforgettable experience. I had no idea then where it would lead.

Once home, I continued working three days a week on my grandparents’ stalls and resumed my training as a swimming instructor at Edge Hill. I viewed my time on the tour as a crazy adventure, telling the story over and over and continuing to wear my lanyard and backstage pass for weeks after the gig. Mike and I had decided to keep in touch, though we weren’t in any kind of a relationship. The whole event seemed like a chapter from some other life, or the most exciting holiday, and I didn’t expect anything more to come from it then. After the interruption to normality, life would continue as before, at least for the time being.

I had no idea how short a time this would be.

When the phone rang, the woman at the other end introduced herself as Eve Carr. She told me she owned the merchandising company I had been working for and asked if I’d liked selling T-shirts. Apparently, she’d heard I’d been pretty good at it.

I told her I’d had a great time, not expecting for a minute that she was calling to ask whether I would be interested in going on another tour. I said I would be interested, guessing that she meant with Elvis Costello. But no, it was going be with a band called Rush. Six weeks, across Europe.

‘Wow,’ I said. I was still riding the high of my first tour experience and didn’t hesitate to say Yes!

I would be paid, she told me. I didn’t ask how much as it wouldn’t have made any difference: I was being offered the chance to go on tour across Europe with a band – never mind that I didn’t know who they were until later. Yes, I know, but progressive rock wasn’t my thing.

Eve whisked me through the itinerary. Gigs in all the major cities in the UK, then on to Paris, Belgium, Sweden, Norway, Germany and Switzerland, culminating at the Pink Pop Festival in Geleen, Holland, where Rush would be performing as part of a line-up including The Police, Peter Tosh, Dire Straits, Average White Band, Masada and Elvis Costello. Could I be in London on a certain day?

I immediately said I could, only afterwards looking at the calendar. There wasn’t anything in the world that would have kept me from going.

Joining the Elvis Costello tour had meant spending a few days away from home in the south of England. Joining the Rush tour would mean spending six weeks travelling all over England and across Europe too. I hadn’t had any misgivings about the first, but this second trip was something else. After my initial delight and desire to grab the opportunity with both hands, reality started to set in. It wasn’t just being away from home, it was going away with a band I knew nothing about to places I had only the vaguest concept of, if I’d heard of them at all. There was no Google then to find out who Rush were, no Google Earth to make virtual reconnaissance.

A friend’s brother played me Hemispheres, the band’s sixth album, which had been released the year before. As I listened to the bizarrely titled first track, I looked bemusedly at the album cover which featured a naked male ballet dancer standing on a brain pointing at the Minister of Silly Walks. I opened out the album booklet and looked at the portraits of the band members – Alex Lifeson, Neil Peart and Geddy Lee, who looked to be wearing a sort of kimono – and wondered what I had let myself in for. I could hear that they were excellent musicians, but I wasn’t struck on what I heard.

After ten minutes or so I asked, ‘How long is this song?’

‘This is the fourth part,’ said my friend’s brother.

I wondered whether Geddy Lee’s voice would last the tour.

When the day came for me to take the train to London, my friends went with me to the station to give me a send-off, for which I’ll always be grateful to them. We had some time to kill before my train was due to leave and, on a whim, we decided we’d go to watch the dog racing. This wasn’t something we’d ever done before, but for the hour or so we spent watching the dogs tearing round the track, I wasn’t thinking about my impending departure, which was just what I needed.

When I got on the train, having stuffed my bag up on the luggage rack and pulled down the window to lean out and say goodbye, I was assailed by doubts. What was I doing, a girl of nineteen from a small village in Lancashire, going on a tour of Europe with a Canadian rock band I didn’t even like? I didn’t know the answer and I was scared. I thought about getting off the train.

I could have done. I didn’t have to go.

But what if I didn’t go? What would happen then? I didn’t know the answer to that question either, and was confident I didn’t want to. What was there to be scared of – the unknown or not knowing the unknown? The latter, without a doubt, was the possibility that frightened me more. So I waved goodbye as the train pulled out of the station, pushed up the window and took my seat.

That night I would be staying with Lynda the T-shirt seller, recovered from her pin-badge poisoning. I disembarked at Euston and took a cab to Blackheath where she lived. It was very late when I arrived, and after an awkward ‘How are you’, I was given her sofa to sleep on.

The next day we were to take a hire car and travel in convoy with the band. Merchandisers would travel separately to the band and load up their vehicles with stock. I would soon learn about the other items of luggage – huge amounts of cash stuffed into carrier bags. Thousands of pounds in notes and coins of various currencies all jammed into supermarket plastic.

During the one week touring with Elvis Costello, all I’d done apart from selling T-shirts was roll up posters. I realised that there was much more to merchandising than I had thought. I learned about stocktaking, form-filling, budget-setting and forward planning. My poster-rolling skills didn’t go unexercised, however. As the youngest member of the merchandising team, I found myself sitting on the floor tightly rolling hundreds of posters, securing them with elastic bands and sucking my paper cuts.

I learned about the dynamics of life on the road and how the camaraderie that prevailed at the beginning of a tour gave way, after several weeks of close and constant proximity, to bickering and bitchiness and even outright belligerence. Relations could hardly have been helped by the wretchedness of our travelling conditions: wrappers and takeaway trays everywhere; cups and cans strewn about, crammed in car doors and filling the footwells; the ashtrays overflowing with cigarette ends – disgusting. The pervasive cigarette smoke was the worst. It staled the interiors of the vehicles and everything in them including the new merchandise.

After the shows we could escape to the cleanliness of our hotel rooms, only to have to return to the squalor in the morning as we hit the road to get to the next gig.

I was sharing a hotel room with Lynda. She was in her thirties, and I could tell she resented my youth and the attention I received because of it. From the outset she made it quite clear she wasn’t going to be my mother, which she was in fact just about old enough to be. Yes, that’s a little bitchy but, well, she started it.

My first night selling merch, I worked with part of my focus on the music. At one point I stopped mid-sale and applauded the band. What little I had heard sounded good!

‘What are you doing?’ Lynda snapped at me from her stall.

‘I’m applauding,’ I said, bewildered by the question.

‘I can see that, but don’t!’

I frowned, about to ask why when she went on, ‘It’s just embarrassing. You’re part of the crew and the crew doesn’t applaud.’ I must have looked upset because she sighed. ‘Instead of applauding we give a nod of recognition that all was well with the show. All right?’

I nodded but still felt a bit like a dumb kid. This was the first moment that I really understood that my perspective had to change. I was no longer a member of the audience.

When Eve first offered me the job she must have presumed that I’d be aware how things worked on tour, but having no real experience of touring, I wasn’t. I did not know that I could eat the food provided for the band and crew or that I had a daily cash allowance to buy whatever I needed while away – Lynda was apparently supposed to tell me these things but never did. The result was that I lost a lot of weight on my first tour. One night I stole a bottle of Coca-Cola from a hotel minibar for nourishment.

I didn’t have much time to worry about Lynda or living expenses, though. Rush were a merchandising marvel, shifting more stock than any other band in history. The show would finish at eleven and we would still be selling merchandise at three in the morning. If someone wore an extra-large and all we had was small, they’d take the small. It didn’t matter if it didn’t fit, the fans just had to have the T-shirt to take away with them.

Meeting demand was a constant struggle. The manufacturers must have been working day and night to produce the merchandise.

For the second tour with Rush that I went on, Gerry Bron, of Bronze Records, used to loan us his plane so that each day the merchandise could be flown from the manufacturing unit to the venue. The queues (I use the word loosely) were always enormous. If there was a group of friends all wanting T-shirts, they’d usually designate one person to join the queue and buy them all for them.

The worst queue I ever saw in my long career was also on my second tour with Rush, at Deeside Leisure Centre, in Flintshire, North Wales. The ice rink had been covered over to convert the hall into an auditorium. The main entrance had been closed off, so the audience entered through the emergency exits along the side of the building opposite the front doors. This meant that the fans had to cross the auditorium to get to the foyer where we were selling the merchandise. The doors opened and the fans started to pour in, a queue quickly forming at the merchandise stalls.

Before long the queue was so long that it had to wind through into the auditorium. We were selling as quickly as we could, just not quickly enough. The queue grew along the entire edge of the auditorium, blocking off the entrances through the emergency doors. The fans were asked to move out of the way of the doors, which they did, but the queue was still growing as more fans streamed in, winding in on itself like a maze until it couldn’t grow any more. The auditorium had been completely taken over by the queue to buy merchandise. There were still fans outside, pushing their way in, while the queue, with no possibility of extending, was swelling instead of lengthening.

It quickly reached the point where something had to give.

One moment, Lofty, one of the roadies – who was not a small man! – was to my right, standing by a glass door connecting the foyer to the auditorium. The next moment he was under it, part of the back wall having collapsed with the force of the crowd on the other side. The fans, who till then had been getting increasingly impatient and noisy, only became more so as they pushed their way to the stall, stepping over the rubble.

Things had got completely out of hand. Lurch, Rush’s tour manager, squeezed through and told us that we would have to stop selling. We packed up the stall and the disappointed fans poured out of the foyer into the auditorium to watch the show. If we hadn’t stopped selling they wouldn’t even have seen the band; they’d have spent the entire night jostling to buy T-shirts.

Selling merchandise was exhausting work but a lot of fun. Though I couldn’t call myself a fan, I loved being part of Rush’s company. They weren’t pompous or preening, though they had every right to be given their extraordinary talents and dedicated following. With my tour pass, I was in the service of the priesthood. And once I discovered that I could partake of the breakfast, coffee and lunch that was provided by the caterers, I no longer had to worry about scrimping.

It was only later that I discovered it wasn’t only my age that Lynda held against me. Before I’d been given it, a friend of hers had wanted my job. So as not to be deprived of her company, she invited her friend to follow the tour across Europe. In Holland we had a couple of days off and Lynda took off with her friend in the merchandising car along with all my belongings, leaving me with no means of transport, no money and no change of clothes.

Thankfully, there were others who looked out for me. I’d become friends with Geddy Lee’s roadie, Skip, who was from the States and, at twenty-two, the youngest member of the road crew. Nothing happened between us, but because we were the youngest of our respective teams we had something in common. I also got on well with one of the caterers and two guys from the lighting team. I think they accorded me a certain amount of respect because I was there to work, not to sleep with the band or crew. On the days off when I had no money, others saw that I didn’t go hungry. One night, when we arrived at a hotel, I found that a room hadn’t been booked for me. I was going to sleep on the bus, but someone booked me in.

Life on the road wasn’t all tensions and tempers. Strong friendships are often born of shared trials, so with plenty of the latter, the former grow.

By the time we reached Germany, halfway through the European leg of the tour, I was exhausted. I thought I must be ill. I was young and fit and up till then had been in good health, yet I found that I just didn’t have the stamina to keep up with everyone else. How, I asked myself, did Lynda, in her thirties, manage to get up at the same time as I did having gone to bed at four or five in the morning?

I asked her one day and she took me to one side. Conjuring a small bag of white powder, she asked me if I’d ever tried coke. I said I hadn’t. She cut me a line and I sniffed it up. She looked at me as if to say, did that answer my question?

It didn’t. All it did was block my nose and made me feel like I had a cold. How could this possibly be a substitute for sleep? I thought she must be mad.

It was a disappointing initiation and it was a long time before I tried it again.

One of the things which makes festivals so much fun is that the various bands and their crews tend to stay in the same hotel. This was how it was in Geleen, at the end of the tour. The night before the final show, we all went down to the bar. The Police were sitting on a sofa off to one side. I went to order a drink and Sting joked to the barman that I was too young to be served. The barman looked at me, uncertain now whether he should serve me. He asked if I had any ID. I hadn’t.

Sting said he was joking and had no idea how old I was.

‘How old are you?’ said the barman.

‘Twenty-one?’ I said, cursing myself for my intonation.

The barman said he was sorry but, without any ID, he couldn’t serve me. Sting got up from the sofa, came to the bar and asked me what I’d like to drink. I said I’d have a rum and Coke.

‘Rum and Coke,’ said Sting.

The barman said he was sorry but he knew that the drink was intended for me and since I hadn’t presented any ID to show that I was of legal drinking age, he couldn’t serve the drink.

‘Oh for—’ said Sting, breaking off with a sigh. ‘Sorry, young lady.’

A little pissed off that everyone else was getting drunk and I wouldn’t be, I told Skip what had happened. Skip then told Geddy Lee, who went and hired a private room furnished with a bar and invited me to join the Rush crew to celebrate the end of the tour. In gratitude, I drank everything that came my way and was duly wrecked by the time Skip, Geddy and I left the party together. We went up in the lift and I stumbled out onto my floor, reaching the door and putting my key in the lock before sliding down to the carpet in a stupor. Geddy didn’t reach his floor and fell asleep in the lift.

The next morning, I woke in the hallway, my key in the door to my room, the cleaner hoovering around me. Geddy was still asleep in the lift, having spent the night travelling up and down, thoughtfully undisturbed by the other passengers.

Later in the day, when Geddy had come round, we made our way over to the venue. Usually with festivals, in order to reduce the amount of time spent setting the stage between the various acts, the stage is set in two halves, the band playing first having their equipment set up at the front half of the stage, the band going on after them at the rear half, so that once the first band’s equipment has been cleared away, all that has to be done is bring the second band’s equipment forward.

The stage, as you’d expect for a festival, was very high and, these being the days before health and safety, there was no back to it, no barrier at all. One of the roadies took a step backwards and fell from the stage. There was a sickening thud and a cracking sound as he hit the concrete below.

I ran over from where I’d been and found Mick Jagger kneeling in front of me, having run over from the other side of the stage. He was asking the guy if he was OK and asked me if I knew who he was. I told him he was one of the roadies. Over Mick’s shoulder, I saw Jerry Hall was with him. Mick asked her to get someone to call an ambulance.

I couldn’t believe it. Mick Jagger. Right there. Kneeling with me beside the injured roadie, whose groans of agony reminded me that this was no time for being starstruck.

We stayed with him till the paramedics arrived and he was taken off on a stretcher. It turned out that he’d broken his leg. Bad as this was, with the height of the stage it could easily have been a lot worse.

The tour finished and I went home. Getting off the train at Preston station in my Rush shirt, I took a cab straight to the high school where my mum worked and waited for her in the car park. I was so excited to see her as we hadn’t had any contact for the duration of the tour. That probably sounds strange today, especially since I had such a remarkable relationship with my mum, but this was a different time. Mobile phones didn’t exist and making a phone call to another country was very much a privilege of the rich and famous or something saved for special occasions. As for phoning from a hotel while we were away, I only had to look inside the information booklet on the hotel dressing table to know that that was completely beyond my pay grade.

I will say that the lack of contact made the reunion extra-special when it came.

Hugs over, she asked me how it had been. I told her about my adventures and also told her how much money I’d come back with: £1,300 in cash, in addition to the £15 per diemsfor six weeks that I hadn’t received thanks to Lynda – just a little short of £2,000 in all.

My mum, having put up with I don’t know how much criticism those weeks I’d been away (‘Your daughter’s doing what . . .? And you let her . . .?’), marched back into school and told her cynical colleagues that her nineteen-year-old daughter had earned more money that month than the headmaster. I can still imagine her smile.

CHAPTER 2

Learning the Ropes

NOT LONG AFTER MY TIME WITH RUSH, Eve called again – this time to offer me another, permanent job. Within the space of six months, I’d gone from being a bored teenager not sure what I wanted to being offered a job that might let me tour the whole world. I could feel that this time was different. This time I was leaving village life behind for good, on my way at just nineteen years old.

I remember the excitement filling me at the prospect of this job – working with rock stars, with so many backstage passes to come and so many countries to see. I knew this was what I wanted, though I didn’t know what to expect – which was part of the appeal, of course. I wanted a life out of the ordinary and here it was.

It’s only looking back now that I realise how young I was, and how quickly it had all happened. Perhaps that’s why it wasn’t until I was on a train from Preston station to the offices of Holy T-shirts at 15 Great Western Road in London that the reality started to set in.

Sitting in the carriage, staring out of the window, I was assailed by the same doubts that had come upon me when I was leaving to go on the tour with Rush. What was I doing? I asked myself. Elvis Costello had been an adventure and Rush a bigger one, but if I kept going down this path, it would become my life. Was this what I wanted? If it wasn’t, now was the time to decide. I didn’t have to take it, after all. I could call the offices, tell them I’d changed my mind. I could apologise and thank them for offering me the opportunity, then, when I was back home, I could forget about it all, the embarrassment fading while I—

While I what? What was there for me back in the village? What was there that I wanted back in the village? Scared as I was, I knew that I was much more scared of a life in slow-motion out in the provinces – a life of nine-to-five, cooking and cleaning, raising a family, waiting for the weekend . . . Yes, I was definitely much more scared of that. The train pulled into Euston station, my mind still racing.

That is until I noticed a sign saying ‘Take Courage’ on the side of a pub. It might have been written just for me. Any trace of indecision left in me vanished then. Whenever I’ve been travelling on the line since, I’ve looked out for that sign.

When I got off the train, lugging my suitcase, I realised I didn’t know how to get to the offices – particularly awkward since there I would find out all the details of my new assignment including, crucially, the band I’d be touring with. I called the telephone number I’d been given, explained who I was and asked for directions. Somehow I managed to find my way there, emerging from Westbourne Park tube station and, remembering to turn left, heading up Great Western Road. Passing over a canal bridge, looking at the pubs along the bank, I thought how this strange place would soon become familiar – provided I did a good job and they liked me, that is.

I carried on up the street, checking the house numbers as I went. Sure enough, there it was, number fifteen – a white stuccoed Georgian terraced house, four floors including a basement, each one occupied by a different aspect of the music business. Apprehensive, I stepped up to the door, put down my suitcase and pressed the buzzer. A woman’s voice came over the intercom and asked me who I was. I told her, there was a buzz and a click, and I entered the offices of Holy T-shirts.

My very first impression was one of absolute chaos. There were people bustling about with arms full of paperwork, running up and down stairs with parcels and boxes, popping up from the basement, questions and instructions shouted across the several floors. By the main entrance were two reception desks, a sofa and a table.

Behind one of the desks was a frightening-looking woman with long black hair, black eye make-up, a top that left little to the imagination, the shortest miniskirt I had ever seen and a pair of thigh-length boots. It was later in the day that I learned the name she went by: Motorcycle Irene.

Intimidated, I made myself go forward.

‘So you’re Kim?’ she said. Following my eyeline, she saw that my attention had been drawn to a straitjacket lying on top of her desk.

‘Take a seat,’ she said, indicating the sofa before turning back to two men who were standing at the other end of the room. They looked intimidating, and as unkempt as if they had just got out of bed.

I sat down and watched the frenetic activity of the place, my eyes constantly drawn to the frightening-looking woman as she talked with the frightening-looking guys. I was unaccustomed to seeing men with longer hair than most of my female friends, and their attire was a menacing black, slightly torn, adorned with metal badges and even bullets worn as belts around their hips. They didn’t smile. They rather glared as if to say who are you and what are you looking at?

Motorcycle Irene caught my eye and I looked away. When I looked back, she was still watching me. I was feeling very uncomfortable and I’m certain she could see it.

Her eyes glinted and she grabbed the straitjacket from the desk, flicking a look at the two men.

‘Come here,’ she said, beckoning me with a finger.

Leaving my suitcase by the sofa, I went and stood before the desk.

‘Try this on, would you?’ she said. ‘I’d like to see how it looks on you.’

I couldn’t tell whether she was joking. She didn’t seem to be. I looked from her to the two guys. They nodded as if to say I should go ahead. I pulled the straitjacket on and the woman came round the side of the desk to tie it up at the back.

‘Now try and get out of it,’ she said.

As I stood before her and the two guys, wriggling inside the jacket and realising immediately that there was no way I was getting out of it by myself, I felt like a rabbit caught in three sets of headlights. They were all very amused, their faces creasing with laughter.

I struggled to get out of the jacket, my face burning. Having been so anxious to make a good first impression, hoping to come across as cool and cultivated, I was mortified. But no one else around so much as batted an eyelid, as if this kind of thing was an everyday occurrence. Doubt reared its head once again. What on earth had I got myself into?

Mercifully, a buzzer sounded and a voice asked that I be sent up. Irene released me from the jacket and told me to go up to the top floor. She said I could leave my suitcase down there in reception. Reluctant as I was to do so, I wasn’t going to lug it upstairs with me and make an even bigger fool of myself, so I left it there and made my way over to the stairs. Looking up, I could see all the way up to the top floor.

I reached the first floor and looked through an open doorway into an office containing several massive desks piled with paperwork. Behind one desk was a guy poring over a mess of documents. Also in the room was a woman taking notes. A blonde, she was the opposite of the receptionist – equally striking, but much more glamorous. I carried on up to the top floor, where, through another door, behind another overloaded desk, sat my new boss, Eve Carr.

I had been anxious about meeting her. Over the phone she had sounded brusque, aggressive even. I realised, however, that it was her Swedish accent that, sounding harsh to my ear, had led me to form this intimidating image. Once we were introduced, she asked me to start sorting badges and patches into batches of a hundred and bag them up. The rooms were crammed with boxes of merchandise, so I found a piece of floor to sit on and set to work.

It soon got to lunchtime, and as it looked like everyone in the office was going to the same place – a pub on the canal – I went along with them. It was only then that I was introduced to the two men who had had a laugh at my expense with the straitjacket. ‘This is Lemmy and Eddie from Motörhead. You’ll be working quite a lot with them.’

That revelation gave me pause. I didn’t even like heavy metal, and as for the look of them . . . yikes.

Doubt crept in again. Did I really want to do this?

After this beginning, it’s rather ironic how much I learned from those men in the end.

Apart from the pub, the other place to get lunch was a café across the road, where we regularly went for coffee, breakfast and snacks during the day, as did many of our clients. It was a tiny place, with only five or six seats and a bar running along one side, but the walls were covered in signed photographs of its rock ’n’ roll patrons.