Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

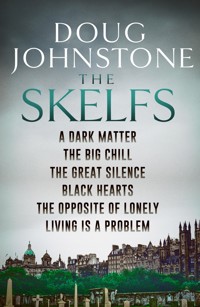

- Serie: The Skelfs

- Sprache: Englisch

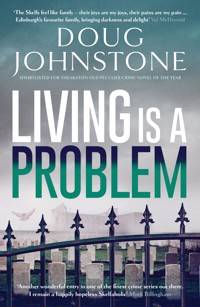

Drones, gangland vendettas, a missing choir singer, disturbances in the cemetery, PTSD, panpsychism, and secrets from the past … This can ONLY mean one thing! The Skelfs are back, and things are as nail-biting, tense and warmly funny as ever! `The persistence of love in the Skelf household, no matter what fate flings at it, is reassuring and life-affirming´ The Times `The Skelfs feel like family – their joys are my joys, their pains are my pain … Edinburgh's favourite family, bringing darkness and delight´ Val McDermid `Another wonderful entry in one of the finest crime series out there. I remain a happily hopeless Skelfaholic´ Mark Billingham _______________ The Skelf women are back on an even keel after everything they've been through. But when a funeral they're conducting is attacked by a drone, Jenny fears they're in the middle of an Edinburgh gangland vendetta. At the same time, Yana, a Ukrainian member of the refugee choir that plays with Dorothy's band, has gone missing. Searching for her leads Dorothy into strange and ominous territory. And Brodie, the newest member of the extended Skelf family, comes to Hannah with a case: Something or someone has been disturbing the grave of his stillborn son. Everything is changing for the Skelfs … Dorothy's boyfriend Thomas is suffering PTSD after previous violent trauma, Jenny and Archie are becoming close, and Hannah's case leads her to consider the curious concept of panpsychism, which brings new danger … while ghosts from the family's past return to threaten their very lives. Funny, shocking and profound, Living Is a Problem is the highly anticipated sixth instalment of the unforgettable Skelfs series – shortlisted for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Novel and Theakston Old Peculier Crime Book of the Year – where life and death become intertwined more than ever before… _______________ `A series that keeps getting better and better. Readers have come not only to know the Skelf family but care for them too, which makes their increasingly dangerous predicaments all the more thrilling´ Scots Whay Hae Praise for The Skelfs series **SHORTLISTED for Theakston Old Peculier Crime Book of the Year** **SHORTLISTED for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Novel** `Some of the best female characters in crime fiction´ Sarah Hilary `If you loved Iain Banks, you'll devour the Skelfs series´ Erin Kelly `An addictive blend of Case Histories and Six Feet Under´ Chris Brookmyre `Wonderful characters: flawed, funny and brave´ Sunday Times `Underlines just how accomplished Johnstone has become´ Daily Mail `Johnstone never fails to entertain whilst packing a serious emotional punch´ Gytha Lodge `An engrossing and beautifully written tale´ Herald Scotland `One of the greats of Scottish crime fiction´ Luca Veste `Gripping and blackly humorous´ Observer `A must for those seeking strong, authentic, intelligent female protagonists´ Publishers Weekly

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iThe Skelf women are back on an even keel after everything they’ve been through. But when a funeral they’re conducting is attacked by a drone, Jenny fears they’re in the middle of an Edinburgh gangland vendetta.

At the same time, Yana, a Ukrainian member of the refugee choir that plays with Dorothy’s band, has gone missing. Searching for her leads Dorothy into strange and ominous territory.

And Brodie, the newest member of the extended Skelf family, comes to Hannah with a case: something or someone has been disturbing the grave of his stillborn son.

Everything is changing for the Skelfs: Dorothy’s boyfriend Thomas is suffering PTSD after previous violent trauma, Jenny and Archie are becoming close, and Hannah’s case leads her to consider the curious concept of panpsychism, which brings new danger … while ghosts from the family’s past return to threaten their very lives.

Funny, shocking and profound, Living Is a Problem is the highly anticipated sixth instalment of the unforgettable Skelfs series – shortlisted for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Novel and Theakston Old Peculier Crime Book of the Year – where life and death become intertwined more than ever before…

ii

iii

Living is a Problem

DOUG JOHNSTONE

iv

This book is dedicated to everyone I’ve ever been in a band with. Maybe we didn’t realise it at the time, but we were doing something worthwhile.v

Contents

1

Jenny

She loved Saughton Cemetery because it was ordinary. The ancient graveyards in the centre of Edinburgh were full of famous people, ostentatious monuments, statues of long-dead blokes – and they were always blokes – who built the city or led the enlightenment or colonised the world. Those cemeteries had plenty of tourists snapping pics for their socials, but none of them would know Saughton even existed. This place was for real dead people. Jenny’s kind of people.

They were burying Fraser Fulton, who died in his sleep from a suspected heart attack. He’d had a post mortem, though, because any death in Saughton Prison is suspect. The fact that you could see the high walls and razor wire of the prison from here added a little poignancy to proceedings – he was being buried within sight of the place he spent his last days, banged up for attempted murder in some gang-related thing Jenny had read about in the Daily Record.

She looked around. Fraser was popular, two hundred mourners, his coffin to the side of the grave on wooden planks.

Leading the funeral party were Fraser’s widow, Ellen, and her grown boys, Harvey and Warren. The men were big and hard, squeezed into suits, pinched faces, shaved heads. Ellen wore a classy black suit with trainers, like she might need to make a quick getaway. Her dyed-blonde hair was elegant and her nails and lipstick a demure purple. A large spread of white chrysanthemums spelled out DAD on top of the bamboo coffin.

The Fultons had seemed like a traditional family, so Jenny was surprised they’d gone along with the biodegradable coffin and the 2Skelfs’ no-embalming rule. Her daughter Hannah had suggested that rule and they all agreed to putting no more poison in the ground.

Jenny threw Archie next to her a look. He’d been there for her when she needed it, through the mill with an abusive and murderous ex-husband. She’d lost herself for a while, but thanks to Archie and her family, she was much more together now. And she was happy doing funerals. She’d resisted the family businesses for so long, both the funeral directors and the private investigators, but she’d come to realise that this – a sense of peace and quiet at a stranger’s funeral – was what she needed. Other people’s grief was so much easier to handle than her own.

She took the netsuke from her pocket, Archie smiling at her. He’d made it for her a couple of years ago, a carved wooden fox in the Japanese style. She kept it on her like a talisman. Since she’d been carrying it, her life had got better. She wasn’t the kind of person to believe in superstitions, but it felt good nonetheless.

The Church of Scotland minister was a large man with slicked-back hair like a Teddy Boy. Harvey Fulton stepped forward as the minister spoke and draped a Hearts scarf over the coffin. Made sense, Tynecastle was just a walk up the road.

From this corner of the graveyard, Jenny could hear the Water of Leith burbling behind them. The river wrapped round the cemetery and the nearby allotments on three sides. There were often allotments next to cemeteries, and Jenny wondered if there was something in that. Maybe the corpses in the ground had fertilisation power, good for your courgettes.

This wasn’t the scenic part of the Water of Leith that fed into the sea, or the section that trickled through woodland near the Gallery of Modern Art. Here it ran between industrial estates and gyms, car dealerships and supermarkets. Across a fence were rows of sixties terraces, pebble dash and orange brick, the kind of house that was everywhere in Edinburgh outside of the centre. The city that tourists never saw. Another reason why Jenny loved it here. 3

She turned to Archie, took him in. Shaved head, neat beard, some grey in it now. Solid body, muscle not fat. She kept her voice low. ‘Do you think he really died of a heart attack?’

‘Coroner said so.’

‘Seems suss, in prison and all.’

‘You saw his body, he clearly liked to eat and drink.’

Jenny liked spending time with Archie, they’d developed a deep and solid friendship. They were the same age, but Jenny always used to think of him as older. Probably because he seemed more mature than she ever felt. He’d accumulated skills and knowledge over time, whereas she felt like she’d spent decades struggling to keep her head above water. She had never felt in control, until now. She liked it, and she liked him.

She became aware of a noise above the minister’s eulogy and the faint traffic rumble from Longstone Road. The minster heard it too, stopped speaking. A few mourners glanced at each other.

‘Look.’ Archie nudged her and pointed at the sky.

She saw a drone coming in fast, high above the allotments then swooping down and arcing over the mourners before hovering above the grave. Some arsehole was buzzing a funeral, what the hell?

The drone had come from the west, where the prison was. Jenny had heard stories about drones being used to smuggle phones and drugs into prison, but she’d never heard of anything like this. And besides, the drone was just sitting there, twenty feet off the ground, filling the air with noise.

The mourners shook their heads, outraged.

‘Ever seen this before?’ Jenny said to Archie, as they both stepped forward.

‘No.’

Jenny noticed a canister strapped to the drone’s underbelly as it turned left and right, checking everyone out. She looked around the graveyard, but of course the pilot could be miles away, watching through the camera mounted on the front. 4

‘Wait,’ Archie said, stepping closer. ‘Are those nozzles?’

As he spoke, the six jets on the feet of the drone burst into life, spraying everyone with liquid.

‘What the fuck?’ Jenny said.

Pepper spray. Some motherfucker was attacking their funeral with pepper spray.

The mourners panicked as the drone dropped a few feet, screams and cries as the Fulton boys ushered their mum to shelter under a willow tree.

Tears streamed down Jenny’s cheeks as she tried to find something to cover her face. She blinked, stinging pain in her eyes as she ran for shelter. Mourners were running down the path, covering their mouths and noses, gasping for breath.

Jenny could only catch glimpses through her own stinging eyes. The drone turned left and right spraying in every direction, then swung down to target the Fultons. Warren waved an arm to bat it away but he was nowhere near. Ellen was crying on Harvey’s shoulder, both of them eyes tight shut. The drone seemed to angle to get as much pepper spray as possible on the funeral party, the noise of its rotors like lawnmowers.

Then Jenny saw Archie bend down under a tree that spread over from the allotments, pick an apple from the ground, take aim through tear-stained eyes, and launch it. The apple sailed through the air and hit the drone, taking out two of the rotors. The noise cut out as the drone swayed like a drunk before plummeting, bouncing off Fraser Fulton’s coffin, the remaining rotors tangling up in the Hearts scarf, before it fell into the open grave.

2

Dorothy

The noise in the room made her feel alive. A dozen people making music together, causing the air to vibrate in ways that could move listeners to tears. She wished everyone could experience this sense of togetherness. Being in a band – good or bad, folk duo to orchestra – was a direct link to the earliest humans, beating drums and dancing around a campfire, finding something spiritual in the communal act of creation.

Dorothy looked around the studio loft, the rehearsal space two floors up from the undertakers and private investigators. The sun flickered through the window, dappled by the trees outside. There was sweat in the air from all the members of The Multiverse, a ramshackle bunch of musicians and singers thrown together by chance.

They were playing ‘I Saw’ by Young Fathers, two of the younger members of the refugee choir were big fans. Dorothy loved it, primal and powerful tom beats. She was accompanied by Gillian, the multi-instrumentalist who could play anything, now pummelling away on two floor toms, the pair of them holding the song together. Dorothy’s vintage Gretsch kit wasn’t built for this kind of workout, but she hammered her floor and rack toms regardless, watching for the breaks to play simple, effective fills, occasional cymbal crashes. This song would have enormous power in front of a crowd, it felt like it’d been dug from the earth.

The choir were hollering the words while Zack sat in the pocket on bass, his girlfriend Maria splashing synth swathes over the top, guitarist Will chugging along with a simple riff. His wife, Katy, was in charge of the choir, refugees and asylum seekers 6brought together through her church on Morningside. For many of them, this was the only contact they had with their local communities.

Dorothy shouldn’t really be here just now, she should be dealing with the funeral business, but this nourished her soul. Besides, Jenny and Hannah had stepped up recently, alongside the rest of them. Archie was a stalwart, Brodie had taken on more responsibility, and Hannah’s wife Indy was another rock, stepping into the undertaker role with ease.

Then there was her boyfriend, Thomas, if you could call a retired cop in his late fifties your boyfriend. Dorothy’s mood darkened. He hadn’t coped well after the trauma of last year, being beaten and almost killed by a rogue police officer. She shook her head and turned her attention back to the song, which built to a crescendo of vocals and drums, overlapping between the gaps until they burst into a final flourish. It was one of those songs you never wanted to end.

The kitchen downstairs from the studio was heaving with band members. They never went straight home after rehearsal, the singers especially lingering, catching up, swapping rumours about Immigration Enforcement. They were protected a little by living in Edinburgh, where the local communities supported their cases to stay. But that didn’t stop UK officials trying to extract people.

Dorothy set down pots of tea and coffee on the large, scuffed table, other people clinking mugs, someone getting milk from the fridge. Katy had brought traybakes, millionaire’s shortbread and tablet, Dorothy’s favourite. Insanely sugary, but who cares when you’re in your seventies?

The kitchen doubled as a control room for the funeral and PI businesses. The far wall was covered in two giant whiteboards, a list of deceased and funeral details on one, the other for cases they 7were investigating. The funeral business was booming, recent moves towards eco-friendly undertaking had boosted their numbers. A lot of people were interested in the most environmentally friendly way to dispose of themselves. Dorothy was pleased.

She turned to the massive map of Edinburgh on the adjacent wall. Her home for more than five decades, it had felt like an alien planet when she first arrived here from the golden sunshine of California in 1970. Nowadays, the Skelfs’ funerals and investigations reached every nook and cranny of this intertwined city. The roads and paths were like capillaries and veins, carrying life from Wester Hailes to Leith, Silverknowes to Niddrie.

‘Dorothy?’

She turned to see Faiza and Ladan, heads slightly bowed, hands together. Faiza was Syrian, Ladan from Somalia. Dorothy couldn’t imagine what they’d been through to get here. Faiza had a bright smile, big eyes and wore a headscarf. Ladan had a nose stud, hoop earrings, her hair in short braids.

‘What is it, ladies?’

Faiza threw a look at Ladan and got an encouraging smile in return.

‘Is it true you investigate things?’

Dorothy loved this moment, the start of something.

‘Is it Yana?’ she said. She’d noticed their choirmate had missed a few rehearsals. People dropped in and out, but it wasn’t like Yana to skip practice.

Faiza looked at Dorothy. ‘No one has heard from her for many days. Ladan and I met her often for tea. She has not returned our messages. She has young children. We’re worried.’

Yana was Ukrainian. Her husband had stayed and fought the Russians, but died in combat a few months ago. Dorothy could get her address from Katy. She touched Faiza’s hands and smiled.

‘I’ll look into it.’

3

Hannah

She stood in the courtyard and looked at the Victorian clock tower, blue sky beyond. She read the inscription over the door, Patet Omnibus. She’d looked it up, it meant ‘open to all’. Seemed appropriate for the Edinburgh Futures Institute, although the words were from when the building was the old Royal Infirmary. These days, it had all been developed into Quartermile – luxury flats, cafés and shops, and this big chunk that the university had turned into a state-of-the-art, interdisciplinary body that was all ‘challenge-led’ and ‘co-creative’. Hannah loved the idea of an institute for the future, but their website was written in the kind of vague language that made it impossible to understand what they actually did.

But she enjoyed attending random classes here. Her former supervisor in the astrophysics department had a friend at the EFI, and Hannah had been given the all-clear to attend whatever she wanted. Hannah was decompressing after finishing her PhD on exoplanets. She wanted to do something useful, but also wanted to keep learning new stuff. Which was why she was here. She went inside and downstairs to the lecture theatre, beautiful views over the square at the back, a mix of renovated old brick and new glass. Today’s talk was on something called Integrated Information Theory by Rachel Tanaka, visiting professor from UBC in Vancouver and practising Buddhist priest.

Tanaka had short grey hair and an infectious smile, wore a large turquoise pendant on a long chain over a dark turtleneck, black jeans and chunky trainers. IIT was a dull acronym for something pretty insane, the idea that consciousness was a measurable, physical 9entity that emerged in different systems. The maths and philosophy were beyond Hannah’s understanding, but it implied that consciousness was inherent in everything.

Tanaka began talking about panpsychism within her Buddhist faith, the idea that the universe is conscious, therefore every element of the universe is conscious. Hannah struggled to get her head around it, but maybe it was a cool way of looking at the world, if it made you act with more respect and consideration.

Tanaka moved on to talking about animism within indigenous cultures, where everything from rocks to weather systems were alive and contained an essential spirit. It had many names, from kami and prana in the east to manitou and orenda in North America. She spoke about the Hearing Voices movement, where Western mental-health experts took seriously the idea that people with so-called auditory hallucinations were experiencing something that had to be taken into account, in the same way other cultures had done for millennia. The movement fought the stigma and stereotypes, the accusations of mental illness, that plagued this subject matter in the West.

Tanaka doubled back to talk about the maths of IIT, in its infancy but already mind-bogglingly complex. That always seemed the way – Western science took supercomputers to work out a fraction of what ancient cultures knew all along, that we are part of an animated universe, that we aren’t alone.

The lecture finished to warm applause from the students. For Hannah, the chance to soak this up was a blessing. She didn’t have number-crunching data analysis to do, didn’t have a thesis to write up. She could just listen and learn.

Tanaka packed her notes and laptop away into a Vancouver Writers Fest tote and walked to the exit. Hannah was ahead of her and decided to loiter at the door, but then felt awkward. Tanaka threw her a big smile.

‘Professor Tanaka?’ Hannah said.

‘Rachel, please.’ 10

‘That was fascinating, thank you.’ She felt like a dumb undergrad again, unsure what to say to someone so much smarter.

‘I’m glad you enjoyed it.’

‘Do you really think everything is alive?’

Rachel smiled. ‘It can be a hard idea to get hold of, if you’re not brought up in that culture.’

‘And do you think IIT is the answer?’

‘There isn’t one answer, that’s not how knowledge works,’ Rachel said. She touched Hannah’s arm and they moved to the side of the entrance as the last of the audience filed out. ‘Let me ask you something. Do you believe humans are conscious?’

‘Of course.’

‘Dogs and cats?’

‘I guess so.’

‘Trees?’

Hannah made a face. ‘Maybe?’

‘So where do you draw the line. And why?’

Hannah thought about it. ‘I don’t know.’

Rachel smiled again. ‘With all these ideas – IIT, panpsychism, animism – we don’t have to draw a line. There is no line. The line is a fabrication of Western dualist thinking.’

‘I suppose so.’

Rachel took Hannah in. ‘Are you one of my students here?’

Hannah shook her head. ‘I just got my PhD in astrophysics. I’m trying to work out what to do next. Your work is really interesting.’

Rachel went into her bag and took out a card, handed it over. It was classy and minimal, Rachel’s name and email address, an outline of a tree, branches above the ground, roots below.

‘If you want to talk more about it.’ Rachel pressed her hands together to leave. ‘I’m always looking for smart students.’

Hannah’s phone vibrated in her pocket, which made her fumble her goodbyes. She watched Rachel leave then took her phone out. 11

It was Brodie, who worked for the Skelfs, arranging their communal funerals for people who had no one to mourn them.

‘Hey Brodie, what’s up?’

He was outdoors, wind blowing, trees rustling.

‘I’m at Craigmillar Cemetery. At Jack’s grave.’

Hannah swallowed. Jack was Brodie’s son, who’d died as a newborn eighteen months ago. Craigmillar had a whole section for baby graves.

‘Are you all right?’ Hannah said, looking around the empty lecture theatre. The light seemed too bright suddenly, the air too heavy.

‘Someone’s been messing with his grave.’

‘Messing?’

‘Maybe it’s best if you come and see it.’

4

Jenny

The vibe outside Diggers was one of simmering outrage. The Fultons had booked the pub for the wake and a crowd of people were standing outside now, pouring water from pint glasses into their bloodshot eyes, rinsing out the pepper spray. Inside, the place was rammed with mourners who’d escaped the worst of the attack.

Jenny looked up at the pub sign. It read Athletic Arms, established 1897 but everyone in Edinburgh called it Diggers. It was on a sharp corner of Angle Park Terrace and sat between two old cemeteries, Dalry and North Merchiston. The story was that the pub was frequented by gravediggers back in the day, who would prop their shovels against the bar after a hard day’s graft. Appropriate for a wake, then, even if both those graveyards were full these days.

The Skelfs didn’t always hang around at a wake, but it felt like they should be here. Jenny and Archie were sniffing and blinking as they drank pints of eighty shilling, while the Fulton boys wound each other up.

Jenny looked at Ellen. ‘I think you should go to the police.’

They’d discussed this in the aftermath of the drone attack, but the family of a man who’d died in prison didn’t have a huge amount of faith in the police force. Jenny didn’t blame them. She was ambivalent about cops too, since a few experiences with them as a young woman. That had been reinforced by the Skelfs’ case a year ago, where two cops were discovered to be blackmailing and coercing vulnerable young women, raping them and eventually killing them. That still wasn’t resolved. Don Webster and Benny 13Low were out on bail awaiting trial. The one good cop Jenny knew was Dorothy’s man, Thomas, but he’d retired on health grounds, the shock of last year taking its toll.

‘No cops,’ Harvey said. He was twenty, built like a brick shithouse and livid at this affront to his dad.

‘If only so that it’s on record,’ Jenny said.

Harvey’s brother Warren shook his head, finished his lager and grabbed another from the window ledge outside the pub. ‘We don’t want this on the record.’

It was clear the Fultons would deal with this themselves. Which meant a bunch of violence and more guys ending up in jail. Jenny felt duty bound to offer an alternative.

‘Who do you think would’ve done this?’

Warren and Harvey gave each other a look which didn’t include Ellen, and Jenny wondered about that. Ellen seemed like the kind of wife who knew full well what her husband was like. When she’d come to the Skelf house to arrange the funeral, she was under no illusions about why Fraser was in prison. It wasn’t a miscarriage of justice, he really had tried to murder someone and had been taking his sentence on the chin.

‘He had his faults,’ Ellen said now. ‘But my Fraser was a good man who always provided for his family.’

‘I just thought,’ Jenny said, leaning in to Ellen and lowering her voice, ‘before anyone does anything they might regret, I could look into it for you.’

The funeral stuff had been great for getting Jenny on an even keel, but it had become routine. And the Skelfs were private investigators, right?

‘Jenny.’ This was Archie, a note of warning in his voice. But he knew she was headstrong, and nothing he said would change her mind.

‘You?’ Warren said with a snort. ‘What could you do?’

‘I’m a private investigator.’ Jenny took a business card from her pocket and handed it to Ellen, the one she needed to convince. 14

Warren drank more lager and scoffed. ‘What have you investigated recently?’

Jenny stuck her chin out. ‘I discovered that my ex-husband murdered one of my daughter’s friends. I found him when he escaped from prison. I killed him on a beach in Fife. When his washed-up body was stolen by his sister, I found them both hiding at an illegal camp.’

Warren swallowed and Jenny enjoyed the silence. Hearing it all made Jenny queasy, and she looked at Archie for reassurance. He touched her wrist and sipped his beer.

Ellen turned Jenny’s card in her fingers, gulped from an enormous gin and tonic.

‘Ellen,’ Jenny said. ‘I’m sure you don’t want to see any more of your family behind bars. If your boys do something stupid in retaliation, you’ll never forgive yourself.’

Ellen shook her head and stared at her sons.

‘We can handle this,’ Harvey said, puffing out his chest.

‘I’m sure you can,’ Jenny said, then to Ellen. ‘But someone not personally invested might get better results.’

Archie cleared his throat. ‘Jenny, are you sure…’

She wasn’t sure, but she was following her gut. Dorothy did that all the time, and she was trying to be more like her mum. She gave Archie a kind look, and he raised his eyebrows in submission.

Ellen finished her gin and gave a big sigh. ‘OK. You can start by talking to the Conways. I’ll email you details.’

Warren shook his head and Harvey clenched his fists, but the look Ellen gave them made them both take big drinks and shut up.

Jenny had a case.

5

Hannah

She jumped off the bus at Old Dalkeith Road and walked to the cemetery entrance. Craigmillar Castle Park Cemetery was the city’s newest graveyard, fresh stone wall and iron gates. It was weird seeing a cemetery with only a fraction of its five thousand spaces used up. The driveway down the middle split the grass, modern waiting room on the left, Muslim burial section to the right.

Hannah passed the Catholic area, the spread of newer graves up the hill, the still-empty land on her left. She reached the small section reserved for burying babies, a collection of miniature gravestones huddled together as if they found strength in numbers.

She couldn’t see Brodie to begin with, looked to the back of the cemetery where the woods spread up the slope towards the ruined castle. Over the other side of the fence were the Bridgend allotments, then the university’s playing fields at Peffermill. So much green space in such a small city.

Brodie walked slowly towards her from the bottom of the cemetery. He was tall and gangly, all arms and legs. His suit fitted well but he still looked uncomfortable in it. His wavy hair was cut short, worry in his grey eyes as he reached Hannah.

‘Thanks for coming,’ he said. ‘I didn’t want to bother Dorothy with this.’

He stood awkwardly, rubbing his sleeve.

‘You thought you’d bother me instead.’ Hannah meant it as a joke, but Brodie’s face fell. ‘Mate, I’m joking.’

He tried to smile. ‘Sure.’ 16

Hannah looked around. A handful of rabbits were munching on grass in the distance.

Brodie glanced at the baby graves then looked away.

‘So, want to tell me what’s happened?’ Hannah said.

Brodie tugged his sleeve. Dorothy had bought him the suit when he started working for the Skelfs last year. Hannah and Indy were the first to meet Brodie, at a stranger’s funeral at Mortonhall Crem. Indy twigged that he was turning up to a lot of services. Funeral crashers were rare but it did happen. Brodie had lost his son in childbirth, then split up with his girlfriend Phoebe, as they both struggled to cope. Dorothy had seen that Brodie needed a purpose and employed him in the undertaking business, focusing on the new communal funerals they were conducting.

He pointed up the slope. ‘I was just checking the plot was ready for the Fitzgerald funeral. Spoke to William, the groundskeeper.’

‘I thought Indy was running the Fitzgerald burial?’

‘I’m helping out. Plus it gave me a chance to come and see Jack.’ His eyes flitted in the other direction. ‘Two birds, one stone, and all that.’

He swallowed and Hannah avoided filling the silence. Something she’d learned from Gran, to let people talk.

The wind rustled the trees by the allotments, and Hannah thought of IIT, Rachel Tanaka saying that everything was conscious. The leaves on the trees, the grass under her feet, the tomatoes and cucumbers in the allotments, the headstones around her, the rabbits disappearing over the hill.

‘Come and see,’ Brodie said.

He walked towards the tiny graves and Hannah followed, gazing at the teddy bears on the graves, plastic fire trucks or action figures, heart-breaking pictures of smiling babies, snapshots of potential lives unlived. A few ultrasound scan pictures, one laminated and taped to the tombstone. 17

They reached the last grave on the row, the small headstone read Jack Sweet. Brodie’s surname was Willis, Sweet was his ex-girlfriend’s last name. Hannah wondered how that conversation went. The crushing weight of everyday grief.

‘Look.’

The grass had been disturbed below the headstone, scratch marks in the muddy earth, dirt scattered around the disturbance. It reminded Hannah of a million horror movies. But the digging was superficial, only a few inches. Nevertheless, she couldn’t imagine what it felt like for Brodie.

She looked around the cemetery.

‘It must just be an animal,’ she said. ‘You saw the rabbits over there. Or a fox.’

Brodie shook his head. ‘Why would it only dig here?’ He waved along the row. ‘None of the other graves are disturbed.’

‘Who knows what scents are left by other animals,’ Hannah said. ‘I’m sure it’s nothing to worry about.’

She touched Brodie’s elbow, and he flinched, kept his gaze on the disturbed earth.

‘It wasn’t a wild animal,’ Brodie said. ‘I showed it to William. He’s been working here since they opened the place. He knows when a fox or a badger has been digging. Look.’ He crouched down and touched his finger against the edge of the small hole, pushed against the earth like he wanted to start digging himself. ‘This was made by a sharp edge. William reckoned a trowel or shovel.’

Hannah crouched down too, shaking her head. She stared at the turned earth. Saw a worm wriggling in the muck and smelled the mulch in the air.

‘Who would do something like that?’ she said eventually.

Brodie stood and rubbed dirt between his fingers. ‘Phoebe.’

‘Your ex? Why?’

Brodie closed his eyes for too long, opened them again. ‘I swear to God, this is her. You need to speak to her. Please.’ 18

He didn’t look at Hannah, just turned and walked away.

Hannah saw his shoulders shake and knew he was crying.

6

Dorothy

Dorothy stood with Indy in the front garden watching the two workmen take down the old sign. They placed it on its side against the hedge and Dorothy angled her head to read it: Skelf Funeral Directors in sharp blue lettering from the nineties. These days they felt like a completely different company with a new ethos. She wondered what Jim would’ve made of them now and the direction they were taking.

Indy rubbed Dorothy’s arm as the workmen hoisted the new sign into place: The Skelfs: Natural Undertakers and Private Investigators. Clean lines, sans serif font. Less formal and stuffy.

‘Looks great,’ Indy said.

Indy was a big part of how the business was changing. She’d come to them with facts and figures, environmental-impact reports on traditional embalmed burial and cremation. Had a bunch of new ideas. They were no longer embalming the dead. This was initially a blow to Archie, who’d spent years perfecting his techniques, but he understood. Dorothy had put him in charge of managing their new Seafield Memorial Woods, although so far it wasn’t much more than a big field with a handful of graves. But they had plans to plant thousands of trees, rewild the entire area and make it the most eco-friendly burial site in the country.

They were also offering resomation at the house, had bought a second machine to double capacity. This was water cremation, where the deceased was dissolved in an alkaline bath, leaving remains similar to cremation, with a fraction of the environmental cost. If the bereaved gave permission, the Skelfs stored the 20liquid run-off, which contained no DNA or remnants of the deceased, and used it as fertiliser at the Seafield site. It was all beautifully interlinked. And they had plans for human composting, mushroom-suit burial, and any other eco-friendly tech that developed over the coming years. They were making things a little bit better for a future Dorothy wouldn’t see.

‘Natural undertakers is a lovely phrase,’ Indy said.

Dorothy looked at her. Her hair was a mix of dyed purple and pink, recently cut short in a bob and fringe, which she pulled off because she was so beautiful. Big eyes and cheekbones, winning smile.

Dorothy had decided she much preferred ‘undertaker’ to ‘funeral director’. It implied that what they did was an undertaking, a vocation, that they were at the service of the bereaved. ‘Funeral director’ suggested that the Skelfs were in charge when, really, those grieving should always be the ones in control.

The workmen had fixed the sign to the posts and were packing away their stepladders. Dorothy thanked them both, then they were gone.

Schrödinger stepped from behind the hedge and sniffed where the workmen had been. The adopted street cat walked as if the garden was his dominion. Dorothy admired his confidence.

He walked to Indy, tail up and purring, and wrapped himself around her legs until she picked him up.

She showed him the sign. ‘Look, we’re undertakers now.’

The cat sensed something in the bushes and squirmed free.

Dorothy looked at the white phone box in the corner of the garden, the wind phone they’d been gifted by an elderly Japanese client. It held an unconnected old rotary phone, and the Skelfs let grieving friends and family use it to speak to their dead loved ones. It created permission, a private space to commune with the dead. Dorothy loved it.

Indy had said that wind phones were springing up all over the world, part of a death-positive movement the Skelfs were part of. 21Talking about death in an open and positive way was the best way to deal with grief. Their Communal Funeral project was a part of that too. Dorothy had struck a deal with the council for the Skelfs to conduct the funerals of those who didn’t have anyone to mourn them. Old people who died alone, unknown bodies washed up on one of the city’s beaches, suicide victims with no note, homeless folk who didn’t make it through the night, refugees or asylum seekers living off the radar. Dorothy felt privileged to hold these funerals, to let them know even beyond the grave that their time on Earth meant something.

The crunch of footsteps made Dorothy and Indy turn.

Thomas walked up the path with the aid of a stick, wearing a small backpack. Dorothy’s stomach lurched. He smiled when he saw her but his eyes were dull.

Indy hugged him then went to get on with work inside.

Dorothy looked at him, a lot of white in his short hair and beard now, bags under his eyes, a scar on his cheek and a droopy eye from his injures last year. There was much more damage that was less visible. Stab wounds had meant several rounds of surgery on various organs, the stick was needed because one of his knees hadn’t recovered. Then there were the mental scars.

The violence they’d both been subjected to had somehow created distance between them. Thomas blamed himself because the perpetrators were two police officers from his station.

‘It looks great,’ Thomas said, nodding at the sign. A hint of his Swedish accent underneath the Scottish. ‘Very you.’

‘I hope so.’ She looked at him leaning on his stick. ‘Come inside.’

‘Can’t,’ he said, tapping the backpack. ‘I’m on my way to the charity shop.’

This had become his thing, obsessively clearing out his flat. He’d started with big stuff like furniture and paintings. Now he was on to smaller items. It was so obviously a form of PTSD. Dorothy had suggested therapy, but he’d shut down that conversation 22immediately. She didn’t know how else to help, except just to be there for him.

‘Please,’ she said, rubbing his arm. ‘Come in for a minute.’

He smiled at her but looked at his watch. ‘It closes soon.’

‘I’ll come with you.’

‘I can go on my own.’

‘I know you can, I —’

‘Dorothy.’ He looked at her. ‘It’s OK.’

‘Thomas, I feel like…’ She didn’t even know how to finish that sentence.

‘I know. I know.’

She looked around the garden, at the sign in front of the house. Thought about how she was stepping into the future, how he was stuck.

She sighed and tried to feel the blood moving in her veins.

‘OK,’ she said. ‘Pop in on the way back.’

‘I’ll try.’

She kissed him on the lips, placed her fingers on his cheek, careful not to brush the scar.

She watched him walk away and felt sick.

7

Jenny

Jenny’s main strength as a private investigator was that she didn’t give a fuck. That was really her superpower in life too, it made her kind of impregnable. But as she stood outside the Conway house on Barnton Avenue, she had a niggling worry that she might’ve gone soft over the last year. She’d had no one trying to strangle or shoot her, no one setting her on fire or abusing her. Nothing to fight against.

She needed this, a case to solve involving two-bit rival gangs in western Edinburgh. Barnton Avenue contained some whopping millionaires’ pads, but the Conway place was more modest. However, the signs of affluence were still there, three flashy sports cars in the driveway, a glimpse of a hot tub round the side that looked over the wooded garden. This was moving up in the world for a gangster family, and Jenny wondered what the doctors and lawyers living in the street thought.

She walked up the path and heard dogs barking, then saw three Dobermans slobbering at the side gate. Dobermans had been superseded by nastier breeds as the gangland pooch of choice, giving these dogs a retro charm.

Jenny rang the doorbell and waited. Stepped back and looked at the windows. Turned and looked back down the drive. There was a lot of tree cover in this street, mature gardens. Lots of shelter if you wanted to get up to stuff.

The door opened and a skinny young guy in a dark-blue Adidas tracksuit and trainers frowned at her.

‘Yeah?’

Jenny was taken aback. Jez Conway was more handsome than 24the mugshots she’d seen in the newspapers. He was also young enough to be her son.

‘I’m looking for Marina Conway?’

‘And who are you?’

The dogs were still barking round the side of the house. Jez stepped forward and shouted at them, and they disappeared.

Jenny flipped a business card out and waved it at him. ‘I’m Jenny Skelf, private investigator.’

He sucked his teeth, didn’t take the card. ‘You don’t look like a PI.’

‘And you don’t look like a “property entrepreneur”, Jez.’

He smiled. ‘You’ve done your homework.’

She shrugged.

He took the card, looked her up and down. She was in her late forties now, usually invisible to guys like Jez, but he saw her and she felt a shiver of power in that. She really loved not giving a fuck.