Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

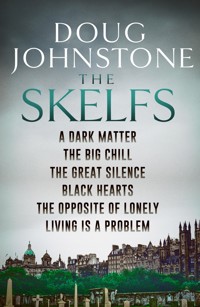

- Serie: The Skelfs

- Sprache: Englisch

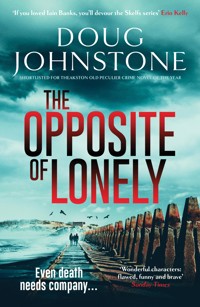

A body lost at sea, arson, murder, astronauts, wind phones, communal funerals, stalking and conspiracy theories … This can ONLY mean one thing! The Skelfs are back, and things are as tense, unnerving and warmly funny as ever! `A terrific read with all of Johnston's trademark warmth and wicked wit in the latest gripping outing for this beguiling family´ A K Turner `Some of the best female characters in crime fiction. Pitch-perfect balance of dark and light … disturbing, compassionate and brilliantly funny´ Sarah Hilary `The Skelfs series just gets better and better! Outstanding characters and a gripping plot … Doug Johnstone is one of the greats of Scottish crime fiction´ Luca Veste ____________ Even death needs company… The Skelf women are recovering from the cataclysmic events that nearly claimed their lives. Their funeral-director and private-investigation businesses are back on track, and their cases are as perplexing as ever. Matriarch Dorothy looks into a suspicious fire at an illegal campsite and takes a grieving, homeless man under her wing. Daughter Jenny is searching for her missing sister-in-law, who disappeared in tragic circumstances, while grand-daughter Hannah is asked to investigate increasingly dangerous conspiracy theorists, who are targeting a retired female astronaut … putting her own life at risk. With a body lost at sea, funerals for those with no one to mourn them, reports of strange happenings in outer space, a funeral crasher with a painful secret, and a violent attack on one of the family, The Skelfs face their most personal – and perilous – cases yet. Doing things their way may cost them everything… Tense, unnerving and warmly funny, The Opposite of Lonely is the hugely anticipated fifth instalment in the unforgettable Skelfs series, and this time, danger comes from everywhere… ___________ `If you loved Iain Banks, you'll devour the Skelfs series´ Erin Kelly `Authentic female characters … Short, punchy chapters mean that the pace is brisk, and Johnstone's deft way of portraying old and new characters means that even novice readers of the series won't be left behind´ Scotsman `An absolute joy to read … full of such wonderful characters, brilliantly realised, with more peril and intrigue. Certainly the best one yet´ James Oswald `Wonderful characters: flawed, funny and brave´ Sunday Times `Johnstone never fails to entertain whilst packing a serious emotional punch´ Gytha Lodge `A unique brand of crime fiction boasting rare heart and depth´ Ambrose Parry `Some of the most unique characters in crime fiction´ Daily Express `Gritty, atmospheric and, above all, profoundly moving. An emotional education in the most unexpected of ways … I loved it´ Sarah Sultoon `A must for those seeking strong, authentic, intelligent female protagonists´ Publishers Weekly `The Skelfs books are brilliant´ Miranda Dickinson ***SHORTLISTED FOR THEAKSTON'S OLD PECULIER CRIME NOVEL OF THE YEAR***

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 377

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Skelf women are recovering from the cataclysmic events that nearly claimed their lives. Their funeral-director and private-investigation businesses are back on track, and their cases are as perplexing as ever.

Matriarch Dorothy looks into a suspicious fire at an illegal campsite, and takes a grieving, homeless man under her wing. Daughter Jenny is searching for her missing sister-in-law, who disappeared in tragic circumstances, while granddaughter Hannah is asked to investigate increasingly dangerous conspiracy theorists, who are targeting a retired female astronaut … putting her own life at risk.

With a body lost at sea, funerals for those with no one to mourn them, reports of strange happenings in outer space, a funeral crasher with a painful secret, and a violent attack on one of the family, the Skelfs face their most personal – and perilous – cases yet. Doing things their way may cost them everything…

Tense, unnerving and warmly funny, The Opposite of Lonely is the hugely anticipated fifth instalment in the unforgettable Skelfs series, and this time, danger comes from everywhere…

The Opposite of Lonely

Doug Johnstone

This one is for Andrew and Eleanor, who set me on this path.

Contents

1

Dorothy

The tide made Dorothy nervous. She watched the waves splashing at the rocky shore and tried to judge how much they’d advanced in the last few minutes. Checked her watch. The thumping bass of an old Orbital tune made it hard to concentrate, and they were near the end of the window for getting off the island.

She tried to calm herself, listened for the lapping waves through the music. She looked across the Forth at Inchmickery, its crumbling concrete wartime defence buildings. It looked like a ghost ship. In the other direction were the three bridges, like architect’s models from this distance. Closer was a flotilla of tankers, clustered around the Hound Point oil terminal.

‘This is quite something.’

Indy’s voice made her turn. Her granddaughter-in-law was in her funeral suit, turquoise hair in a bun, same colour of brooch on her jacket. Big brown eyes, smile on her face. Her luminous running shoes were a concession to the Cramond terrain.

‘It is,’ Dorothy said.

Beyond Indy was the funeral party for Arlo Wright, one of the older members of the travelling community who’d pitched up at Cramond a few months ago and never left. Here on the north side of the tidal island they were far away from prying eyes, couldn’t see the causeway or the village to the south. Another reason Dorothy was nervous, she had no idea how much the water had come in over the causeway. Tourists were always getting stuck on the island and rescued by the coastguard.

Arlo was wrapped in a winding sheet and lying on the remains of a Second World War gun emplacement, an elevated concrete horseshoe with amazing views down the firth. On either side were ruined buildings – gun turrets, searchlights, stores, engine rooms and barracks, all covered in graffiti, colourful shapes and tags. Between the buildings were broken tarmac, overgrown bushes, rocks, scrub grass and rusted metal girders. In amongst it all were twenty people of all ages dancing and drinking, passing round joints and bottles, waving their hands in the air like they just didn’t care.

Dorothy cared. She cared that they might not get Arlo back to the mainland.

The Orbital song was replaced by The KLF. Arlo had been big into the rave scene of the early nineties, fought against the Criminal Justice Bill. There was a healthy anti-establishment, counter-cultural vibe to that scene, it made sense that Arlo would end up in a travelling community. Life is about finding a way through, Dorothy knew that well enough. Although it always ended the same way, as Arlo had found out. His death was sudden, an aneurysm in his sleep. Dorothy also wanted a quick exit, nothing drawn out or painful, not to be a burden to Jenny and Hannah.

She checked her watch again. ‘We need to go.’

They walked over to the mourners, Indy’s hips shimmying with the beat as she bounced like a mountain goat over the rocks. Dorothy picked her way carefully. She was in trainers too, but being in her seventies meant she was less agile, less confident. And a busted ankle here would not be good.

She passed a tumbledown building, windows long gone, sagging roof. In amongst the random graffiti – a woman with a third eye, a black cartoon dog, the Ghostbusters symbol – she saw the phrase ‘Fuck Tha Police’ in thick letters.

She spotted Fara McNish by Arlo’s body, nodding her head to the beat as she accepted a spliff. She was mid-twenties, tall and rangy, round glasses, wavy blonde hair with a red-and-white polka-dot headscarf like Rosie the Riveter. Bracelets and necklaces, dungarees and vegan Docs, scarlet tattoo of a handprint on her shoulder. Fara had come to the Skelfs to arrange Arlo’s funeral a few days ago, knowing exactly what she wanted. This was it, and Dorothy was regretting it. She was all for a party but would’ve preferred if they weren’t about to get stranded.

‘Fara.’

‘Dorothy.’ Fara hugged her and Dorothy felt the genuine warmth of her affection. ‘Have a toke.’

‘Not while I’m working.’ Dorothy pulled at her shirt cuffs. ‘Fara, the tide has turned, we need to go.’

Fara looked around. ‘Maybe we should stay until the next one.’

‘We went over this. You wanted the funeral as green as possible, so Arlo isn’t embalmed. If you keep him here for another eight hours, it won’t be pretty.’

Fara passed the joint to an older woman then stuck two fingers in her mouth and gave a sharp whistle. ‘Move out.’

The party started to shift, a young woman pulling the orange PA speaker on wheels, two men lifting the ropes attached to the ends of Arlo’s body. One was round his ankles, the other looped under his armpits. They slung the ropes over their shoulders and walked, Arlo hanging between them like a deer from a successful hunt.

Indy joined Dorothy at the front as they led the funeral party across the island. They trekked through the trees, past the remains of teenage piss-ups – ashes, blankets, beer cans and vodka bottles. They walked up the hill and Dorothy saw the Dragon’s Teeth, the extended row of large sawtooth concrete structures that marked the causeway. Originally submarine defences, now rotting along with the rest of the wartime detritus.

‘Come on,’ Dorothy called over her shoulder. Indy shared a look with her. The party was strung out behind them, swaying to Leftfield on the PA, the beats coming and going in the wind.

Indy picked the route to the beach, Dorothy and Fara behind. Dorothy saw a low wash sliding across the causeway. The tide came in quickly.

Indy waited for Dorothy and Fara, then they turned to look back. The two tall lads carrying Arlo were kicking up sand, some stragglers behind them.

‘I don’t know,’ Dorothy said, looking at the water. ‘It’s already coming in.’

‘It’s fine.’ Fara stuck her chin out and whistled like a builder again. ‘Let’s go!’

The crowd picked up speed as Fara ushered Dorothy and Indy forward. Dorothy splashed onto the causeway, soaking her trainers, low ripples runnelling across the concrete and seaweed. She started to jog – she was fit for her age but not fast. Indy was at her side, slowing her pace to stay near. Dorothy didn’t want to look back, the path underfoot was uneven and slippy, she could easily trip. The concrete teeth loomed over her as she ran. She heard the thud of techno still coming from the speaker behind her, the splash of twenty pairs of feet through the rising tide. It was past her ankles now, quickly at her shins, soaking her trousers, the cold creeping up her legs, then she was wading through water over her knees.

Indy pulled her elbow. Dorothy risked a glance behind, saw a thrash of water around everyone’s legs as if they were being attacked by piranha, then the music cut out as water got into the PA. The woman pulling it struggled then left it as water reached her thighs. Alongside her, a young couple had toddlers in their arms. Near the back were the two men with Arlo’s body low in the water, the soaked winding sheet clinging to him.

‘Hurry up,’ Indy said, pulling Dorothy’s arm.

She turned and waded as fast as she could, strong currents tugging at her waist, almost knocking her off balance. The raised walkway was up ahead. Indy dragged her along now, the two of them panting, Dorothy swearing under her breath. The steps to the walkway were a few yards away when her foot skidded from under her and she splashed face first into the wash. The icy snap of the water was shocking, pushed the air from her lungs. She scrambled and flailed. Indy yanked her upright, then she staggered a few more yards and felt the first step, pulled at the supporting rope and hauled herself out of the water to the safety of the walkway.

She fell to her knees, struggling to breathe.

‘Are you OK?’ Indy was next to her, panting and spitting out seawater.

She heard footsteps, swearing and grunting as others made it to dry land. They lay around like landed fish, sunshine on their faces, wet stone under their bodies, relief in the air.

Fara stared wide-eyed towards the causeway. Dorothy followed her gaze.

The two men were up to their chests in water, struggling to pull Arlo’s body, waves thrashing through the Dragon’s Teeth and rushing across the firth. A strong wave tore the ropes from their hands. They grasped to get them back but failed. Arlo floated away on the tide, bobbing in the wash like an inquisitive seal, as he made his way out to sea.

2

Jenny

She took a mouthful of coffee and looked out of the kitchen window at Bruntsfield Links. It was busy at lunchtime, pupils from Gillespie’s spilling over the grass, students on their way to classes, workers sprawled out and eating sandwiches. The undulations made it look like a calm, green sea, blue skies above studded with little fluffy clouds. Jenny thought about the bodies buried way below in the old plague pit from five hundred years ago. Her dad’s ashes were scattered there more recently, his atoms now spread out into the universe. Hannah always talked like that, she must be rubbing off on Jenny.

She looked down to see Schrödinger scrape his claws along the back of the armchair, pulling at loose threads. Stupid cat had shredded his favourite place to sleep. He yawned and settled, and Jenny walked to the opposite wall, two huge whiteboards and a giant map of Edinburgh.

The map was dotted with red pins marking places they visited for work – cemeteries, crematoriums, care homes, hospices, hospitals. The hidden spider’s web of the funeral business. One whiteboard was for funerals, names of the deceased, next of kin, notes for the service, cremation or burial, if a viewing was needed. The other whiteboard was for cases. As private investigators, they picked up jobs through the funeral work, plus walk-ins sometimes. Always people in need, worried about partners, kids, parents, money, status, whatever. People didn’t come to a PI if they were happy.

Jenny sipped more coffee. It had been almost four years since she got sucked into the family businesses, but it felt like longer. When Jim died, Dorothy needed her daughter around, so Jenny moved back in and never left. Now, she struggled to remember what life was like before. Simpler, probably, but less meaningful too.

She put her mug in the sink and walked downstairs, closed her eyes and breathed, imagined the smell of smoke. She opened her eyes.

The reception area looked brand new, considering the place had almost burned to the ground a year ago. The case of her ex-husband had gone badly wrong, and her former sister-in-law tried to torch the place. It took six months to get the house into shape again. New wallpaper, floorboards and carpets, furniture and fittings. Tasteful, Scandi-clean lines, more modern than the heavy old oak stuff from before. The inside of the house finally reflected the fact they weren’t conventional funeral directors.

Jenny was supposed to be covering reception, but things were quiet. There was probably paperwork to do, but fuck that. Dorothy and Indy were out at some hippie funeral in Cramond, Hannah was at uni, Archie through the back, at the business end of the building.

Jenny walked that way and got a small carved fox out of her pocket, felt the smooth wood as she rubbed it. It was the netsuke Archie made for her a year ago. She’d kept it close ever since, a small token of friendship that she clung to amidst therapy and drinking, self-destruction and hatred. Weirdly, it had helped. A simple object to focus on while she trawled through PTSD and self-sabotage, pushing away loved ones. She smiled at the fox now and rubbed it for luck. She felt much better than she had any right to, couldn’t have imagined it a year ago.

She stood in the embalming-room doorway and watched Archie. He was taking care of an elderly woman on the metal table, the embalming machine pushing pink milkshake into her carotid artery. Her blood was forced out by the pressure and drained through the jugular vein, running down the gutter at the side of the table and collecting underneath. He held her hand as if reassuring her, but Jenny knew it was to make sure the fluid got to the ends of her fingers so they didn’t rot.

She stepped closer and saw that he’d done her face – mouth and eyes sewn shut, cotton wool up the nose in case of purging. Same down the bottom end, she presumed. Archie kept an eye on the woman’s arms in case of embalming-fluid leaks – old, thin skin or IV holes could do it. Jenny knew all this stuff from hanging out with him, a world of expertise at his fingertips.

‘Hey.’

Archie turned. ‘Hey.’ He nodded at the woman on the table. ‘Wendy Watson, old age, died in her sleep.’

She took him in – late forties, shaved head, neat beard, kind eyes. Sturdy, a little taller than her but not much, solid, reliable. He’d certainly been that over the last year, a shoulder to cry on when things got too much, a release valve from her darkness. They’d taken to going out walking through the streets together, getting to know the nooks and crannies of the city they were both raised in. There was always an undiscovered corner, an unknown vennel or pathway. Edinburgh had centuries of secrets piled on top of each other, and she enjoyed uncovering them with him.

‘Was there something?’ Archie said, checking the pump.

‘Just wanted to say hi.’

‘Hi.’

‘Hi.’ She laughed and sounded younger than forty-eight. Almost happy.

She touched his shoulder then left, back to reception and out the front door, up the path to the wind phone in the corner of the garden. It was a phone box gifted to them by an elderly Japanese client. He had his own in the garden of his Leith flat, and thought the Skelfs could use one. It had an old rotary handset in it, unconnected, the cable hanging down. He’d got the idea from another Japanese man who built one to speak to dead relatives. Then when the tsunami hit he was inundated with people wanting to use it to contact the dead. Most people talk to the dead all the time, of course, but there was something about the specific space of the white phone box that gave permission.

It had certainly been used plenty in the last year. The bereaved much preferred chatting to their deceased relatives or friends in the box than sobbing in a quiet room inside the house. It was wonderfully healthy. So much of traditional western funerals seemed to alienate those left behind from the grieving process. This gave it back to them.

She turned to the house, three floors of Victorian townhouse with Gothic trim, like the Addams family set in posh Edinburgh. She remembered that night a year ago when Stella tried to burn it down. Flames dancing in the doors and windows of the ground floor, smoke billowing into the darkness, their giant pine tree ablaze. Its huge trunk and branches were destroyed in the fire, but an expensive arborist examined samples from the roots, and now suckers were growing from the stump. The tree was reinventing itself, starting again after a hundred years. Jenny thought about that a lot.

She heard a vehicle go past in the street, had a flash of Stella driving away that night with the body of Jenny’s ex-husband Craig in the back of the van. She still hadn’t been found by police, who gave up after a few weeks. Jenny hadn’t bothered looking, she’d gone down that rabbit hole before and more than once it had ended in her nearly dying. She concentrated on therapy, the here and now. Dorothy always talked about living in the moment, that Buddhist shit she was into, and Jenny tried to channel it in her own way.

She opened the door of the wind phone, thought she might have a few words with Dad, check how he was doing. She heard a phone ring. Stared at the handset, the cable dangling loose. Eventually she realised it was her mobile and smiled. She took it out and looked at the screen: Violet.

Her former mother-in-law, Stella and Craig’s mum. She hadn’t spoken to her in a year, since Stella went missing with Craig’s remains.

Jenny stared at the name on the screen for a long time, thinking about messages from beyond.

3

Hannah

The auditorium buzzed with anticipation. They were at the back of the National Museum of Scotland, the event part of the Edinburgh Science Festival, and Kirsty Ferrier had star power. Scotland’s first female astronaut, six months spent on the International Space Station, retired now but in demand for public speaking and generally inspiring young women like Hannah. She looked around. The audience reflected that, mostly young and female.

‘So how are results and analysis going?’ Rose said to her.

Hannah rolled her eyes. She should probably hide the mundane truth from her supervisor, but Rose wasn’t that kind of boss.

‘You know the movie The Road, where they trudge endlessly down an apocalyptic highway with no end in sight?’

Rose laughed. ‘Sounds familiar.’

Rose McAllister was late thirties, red hair, sparky energy and very cool. She’d done some consulting for NASA on a sabbatical, that’s how cool.

‘I’m sure you sailed through your PhD effortlessly,’ Hannah said.

‘I almost gave up at your stage. Considered becoming an actuary.’

‘Not really.’

Rose leaned in. ‘Two years in is hard. Nothing has gone as planned, and now you have to create some narrative about it for your thesis. Think of it as a creative-writing exercise.’

‘I’m not sure my supervisor should give me that advice.’

Rose touched her arm. In truth, Rose’s guidance was one of the reasons Hannah was still at the astrophysics department. Rose was also the reason they were here, she’d scored free tickets because she used to work with Kirsty Ferrier before she became a national treasure.

The lights dimmed and Kirsty walked on stage to excited applause, even a few gasps. Hannah understood, girls of a certain age latching on to a public figure who could show them how to be. She liked to think she was too old for that shit now, but she felt a trill in her belly all the same.

Behind Kirsty, the title of today’s talk glowed on screen: How To Be an Astronaut. She smiled and took the applause. She looked younger than forty-three, lean and fit, black hair in a pixie cut, large-framed glasses. She started talking in her familiar Orcadian accent. On the screen, the title was replaced by a video of her on the International Space Station, the Earth visible out the window, Kirsty bobbing in zero G, a pencil floating past her shoulder. She talked about what it was like in that moment, four hundred and eight kilometres above Earth, one of only a handful of people to have left the planet in the history of humanity.

She talked about her past, Kirkwall Grammar then Edinburgh University to study astrophysics, like Hannah. Postgrad then postdocs at various international institutions, then a sideways swerve into the European Space Agency programme, first as technical advisor, then trainee astronaut, finally a goddamn spacewoman.

‘Fancy it?’ Rose said, nudging Hannah.

Growing up, Hannah had been obsessed with space and the astronauts who explored it. She pored over every detail of the moon landings, the workings of the ISS, the unmanned expeditions to Mars and further into the solar system, probes and satellites out there to glean knowledge of the universe.

These days, she still felt a thrill thinking about that stuff, and seeing Kirsty in the flesh was riveting. But something else gnawed at her. She remembered the first time she talked to Indy about the need for space exploration, not long after they started seeing each other. Indy didn’t understand, pointed out the incredible cost, billions of dollars that could be spent on housing, sanitation or food on Earth. That argument was hard to counter, and Hannah found herself unmoored. But it wasn’t either/or, she finally decided. Space travel for knowledge wasn’t the enemy, rather it was the insane system of capitalism and commercialism at the expense of everyday people. That needed to change. Countless dollars on weaponry and armies, a corporate system that kills Earth’s climate when there was sufficient technology to save it. The current trend for rich, white billionaires playing in space didn’t help. The way Bezos, Branson and Musk treated space exploration as a personal pissing contest made her sick. And the idea that we would colonise the moon or Mars was ridiculous. Indy was right, we had to fix the planet we have.

But for all that, she was still in awe of the woman talking on stage.

Kirsty had moved on to the personal downside of space travel, the physical and mental-health impacts. Loss of bone mass, muscle wastage, fluid movement within the body that could lead to all sorts of problems, including potential blindness. Increased exposure to radiation, reduced red blood cell count, altered biome, the toll of isolation. Hannah hadn’t really appreciated the stress of it all.

‘So it’s not all Bowie singalongs,’ Kirsty said.

She paused to let the laughter subside, narrowed her eyes. ‘But there was something very moving about being on the ISS, when we had a moment to reflect. I definitely experienced what some call the overview effect.’

An image of earthrise faded in behind her.

‘The overview effect is a cognitive shift that some astronauts experience during spaceflight when viewing Earth. Looking at the planet where eight billion people are living and breathing, going about their days, and being separate from that, well… ’ She paused to gather herself. ‘Let’s just say, it makes you think differently about who we are and what we’re doing to the planet.’

Another photograph appeared behind her, blackness above and below a blue curve, a speck of sunset in the middle. Hannah realised it was the surface of Earth from an acute angle, showing the thinness of the atmosphere.

‘This is the thin blue line picture, taken from the ISS. It clearly shows how fragile we are, how little we’re protected from the vast coldness of the cosmos.’

Hannah swallowed. She thought about the gravity holding her in her seat, the thousands of miles an hour she was travelling as the world spun on its axis. She was also hurtling around the sun, racing through the galaxy, always dancing, always moving.

‘Bullshit.’ The voice came from the front of the auditorium.

Kirsty placed a hand at her throat and peered into the gloom. ‘What?’

‘What did you see?’

Hannah saw the man, hoodie and baseball cap, sitting in the third row.

‘I’m sorry,’ Kirsty said. ‘Do you have a question?’

‘What did they do to you?’ He was irate.

Two security guards strode down the aisle towards him. He spotted them and pointed at the stage.

‘You’re a fucking fraud, tell the truth. What happened up there?’

Kirsty was flustered, looked to the side of the stage, then back at the man as the security guards hauled him out of his seat. He kept shouting as they dragged him out of the fire exit.

‘I’m so sorry,’ Kirsty said under her breath. It was weirdly intimate, picked up by her mic, broadcast over the PA. ‘So sorry.’

She looked at the fire-exit door, then around the dark room. She closed her eyes. Hannah wanted her to start talking again, find her rhythm and get the energy back. But she just stood there, saying she was sorry over and over.

4

Dorothy

Dorothy looked around the chapel, renovated after the fire. They’d made a few improvements with the insurance money, including the extension into the garden to house the S900 resomator they bought from a death-research institute in Liverpool. Arlo was lying in front of it now on a gurney, still in his wet winding sheet. Fara stood alongside with half a dozen mourners from earlier in the day. The irony of water cremation for a body just recovered from the sea wasn’t lost on Dorothy. She was mortified that they’d had to get the coastguard out to retrieve Arlo from the wash of the Forth.

Indy was explaining the process of water cremation to the gathering.

‘Arlo goes in here,’ she said, opening the large circular door. The resomator was a large stainless-steel tube, something between an industrial washing machine and a room in one of those Japanese pod hotels. The front door was thick glass, so they could monitor proceedings inside.

Indy pulled the body tray out of the machine. ‘He slides in here, then these jets inside spray hot water at ninety-five degrees and a small amount of sodium hydroxide into the chamber, and Arlo dissolves. The sheet too, it’s biodegradable.’

‘Sodium hydroxide sounds like chemicals?’ Fara said, ducking her head into the resomator.

Indy shook her head. ‘It’s the same process as natural decomposition, just speeded up. Sodium hydroxide is caustic soda, it breaks down body fat and tissue. Water cremation is legally called alkaline hydrolysis, it’s the most eco-friendly funeral possible. It has a tenth of the carbon footprint of normal cremation, plus any heavy metals or plastics in Arlo’s body don’t get burned into toxins, they can be removed from his remains and disposed of properly.’

Fara nodded. ‘What happens to his juice?’

‘It goes down the drain to the water-treatment plant. It’s actually a lot less polluting than the blood we remove from the deceased in embalming.’

‘And what do we get back?’

‘Only his bones are left. We usually grind them up in a cremulator, which gives you white ashes, not the grey stuff from a regular cremation. Pure calcium phosphate.’

‘I think we’ll just take the bones as they are.’

Dorothy tugged at her jacket and breathed, still trying to smooth out the adrenaline from earlier. She and Indy had changed their wet clothes for dry ones when they got back here, and the mourners had done the same before coming up the road. But there was a small pool of seawater under Arlo’s gurney and a briny tang to the air. Dorothy recalled the coastguard boat thrusting into view from Port Edgar. They were used to fishing dead bodies out of the water near the Forth Road Bridge, a famous suicide hotspot. But Dorothy bet they’d never recovered a body from a funeral service before. They were nice about it, respectful when hauling Arlo into the boat, the same when they brought him to the concrete ramp.

Dorothy looked round the chapel now. She couldn’t quite get a handle on these people. They weren’t all dressed like Fara, one guy in jeans and a T-shirt, one with a side parting and button-down shirt, a young woman in yoga pants and strappy top. There was no clear demographic, no tribe she could pin down. Maybe they were just people who’d found each other and made a family. She got that.

‘Any last words?’ Indy said, hands clasped in front of her.

Fara shook her head and glanced at the others. No one spoke.

‘We said it all on the island. That was his celebration.’

Fara came forward and touched her forehead against Arlo’s through the sheet. The others came up and did the same, remaining around the body. Fara gave them a nod and they lifted Arlo from the gurney to the resomator tray then stepped back.

Indy slid the tray into the machine and closed the door. She pointed at the large green button to the side, looked at Fara.

‘Do you want to?’

Fara stepped forward and put her hand on the glass door. She pressed the button and Dorothy heard the water jets flooding the chamber. It looked like a washing machine through the door and Dorothy remembered the water flowing over her shoes on the causeway earlier.

She looked at Indy. Water cremation was her idea and there were others too. Human composting, burial in a mushroom suit. They were trying to move away from embalming, had made it opt-in rather than opt-out. And Dorothy was talking to the council about buying land to create a natural-burial woodland. Indy and Hannah wanted to carve out a niche as the greenest funeral business in the country, and Dorothy couldn’t be happier. She wouldn’t be around to see what happened to the planet in fifty years, but she owed it to Hannah’s generation to stop pumping chemicals into the ground and CO2 into the air.

Fara moved away from the resomator window, signalling to the others to take a look. They took turns gazing at the chamber filling with water and caustic soda. When they were done, Indy held an arm out to usher them out of the chapel. The process took three hours.

Dorothy stepped to the machine and looked inside. She wanted to see something dramatic, like the Nazi face-melt from Indiana Jones, but all she saw was Arlo lying there, the water level rising, showerheads blasting, steam swirling. They’d saved Arlo from the water once today already but in three hours he would be returned to the water forever.

5

Jenny

Jenny wondered how many times she’d walked through the Meadows in her life. From their house in Greenhill Gardens, it was the main route to the centre of Edinburgh. As a kid she’d scuffed her way through the fallen cherry blossom, as a stoned teenager she lay down on the grass and gazed at the stars. As a journalist she traipsed through after hundreds of anodyne stories. As a young mum, she’d lingered with the buggy while Hannah picked up every stick she found. Stood watching her daughter captivated by squirrels darting up trees or magpies flitting between branches.

Now Hannah was married and lived down the road in Argyle Place with Indy, and Jenny was alone. Not completely, she had her mum, a friend in Archie. But she felt lonely. She’d had romances in recent years, and some unhealthy sex. And then there was Craig. His re-emergence in her life, his exposure as a murderer, their obsession with each other, his body washing up in Wardie Bay last year, only for it to be stolen by his sister.

Which was why she was here. She walked up Middle Meadow Walk, past a busker on the clarinet. Two girls with braided hair scooted past on roller skates, cyclists on racing bikes with padded shorts, an old couple wearing too many layers, arm in arm. Jenny felt a twinge at their devotion to each other.

She reached Söderberg and looked around. She didn’t spot Violet at first, was looking for the trim, contained woman from a year ago. Then she scanned again, stopped at the woman in the fancy wheelchair with the young, muscular man by her side. He held a glass of iced tea while Violet tried to suck on the straw. She seemed so much smaller, had lost a lot of weight. Her hair had gone from neat white bob to straggly and yellowing. She had a blanket on her lap despite the warm sun dappling the trees, and her feet were turned inward on her wheelchair footrests. Jenny took her in. A year ago she had to identify Craig’s bloated and burnt body in the mortuary, had to deal with her daughter stealing that body.

Jenny thought about the phone call earlier. She hadn’t answered it, just stared at her mobile until it went to voicemail. When she listened back it was a man’s voice, thick Highland accent explaining that Violet wanted to meet her, giving the time and place. Jenny assumed it was a solicitor or other representative. But this guy seemed more like her carer.

She walked to the table. ‘Violet.’

The man put down the iced tea and stood. Violet’s head was twisted to the side, a tremor running from her hands to her face.

The man put out a hand. ‘I’m Norrie, I look after Violet.’

He had thick arms and Pictish tattoos, brown hair flecked with ginger, kind eyes and heavy stubble. Jenny shook his hand. Norrie pointed at a chair, and Jenny sat.

‘Can I get you something?’ Norrie said, looking for a waitress.

‘No, thanks.’

Violet stared at Jenny, her head jerking like she was receiving signals from somewhere.

‘Motor neurone disease,’ Norrie said. ‘Violet has been fighting it for about a year now.’

He reached over with a napkin and wiped some spit from the corner of her mouth. Violet’s eyes followed him, then after a few seconds she spoke.

‘Thanks.’

It seemed a huge effort of will to control her mouth. She trembled, and Norrie moved the iced tea to a safe distance.

‘I’ve changed,’ Violet said slowly.

The last time they saw each other, Jenny had harangued her on the Royal Mile, trying to find out where Stella had taken Craig’s body. Turned out she didn’t know any more than Jenny.

‘Wondering… ’ Violet’s shoulders jerked and she waited for it to pass. ‘Why you’re here?’

Jenny heard crows in the trees above their table, call and response between branches. ‘Have you heard from Stella, is that it? She’s still wanted for arson and attempted murder, so if you know anything, you should tell the police.’

Violet coughed and struggled to swallow. Norrie leaned in, held the straw to her lips. She sucked a small amount, coughed again. She breathed a few times, shallow ripples through her chest.

‘The police gave up,’ she said eventually.

This was true. Stella was a missing person, after a short window people forget and move on. Unless some glaring evidence dropped in the police’s lap, they would do fuck all.

‘Then what?’

Violet looked at Norrie, leaned on her headrest and closed her eyes. ‘Dorothy?’

Jenny frowned. ‘Mum’s fine.’

‘Retired?’

‘I don’t think she’ll ever retire. She loves the funerals and everything else.’

Violet’s head wobbled. ‘Lucky. You and Hannah.’ She coughed roughly, head banging on the wheelchair.

Norrie placed a hand on the back of her head to cushion it, then squeezed her hand. It looked like a crumpled piece of paper in his big paw. ‘You’re doing fine, Mrs M.’

Violet blinked. ‘Mothers and daughters.’

Jenny tried to think what to say. She’d run the spectrum of emotions with Dorothy and Hannah over the years, but they’d always been there for each other when it mattered. ‘I suppose so.’

Violet closed her eyes for a long time, then opened them.

‘I’m dying,’ she said with colossal effort. ‘I need to see Stella. Will you find her?’

6

Hannah

The roofs of the nearest buildings looked close enough to jump to. Edinburgh’s Old Town was an insane jumble of structures, grown like mould over the last five hundred years. The rooftop clutter on the slope from the castle to Holyrood Palace looked like a crowd jostling to get a glimpse of the sea beyond.

Hannah walked around the rooftop terrace of the museum, ogling the view. South of the castle was Edinburgh College of Art, Heriot’s private school, then the dome of McEwan Hall, where she’d graduated two years ago. Further south she saw another dome, the observatory on Blackford Hill, where she studied. Then east to the colossal knuckle of Arthur’s Seat, glowing in low twilight. She imagined being a giant, striding through the streets, tourists diving for cover as she lumbered around the city’s hills, lifting roofs, finding secrets underneath.

‘Hannah.’

Rose held two champagne glasses and offered her one. She took it and looked around. Maybe a hundred people, and she wondered how many had been at Kirsty’s talk, or if they just wanted to be in the proximity of celebrity. Maybe that was unfair. In amongst the invited guests were lots of museum staff, and Hannah wondered if there was any security here. She thought about the event derailed by the heckler, how Kirsty eventually got things back on track, answering questions, then finishing a few minutes early.

‘The uni are paying for all this,’ Rose said, waving a hand. ‘And yet they just cut my pension by thirty percent.’

Edinburgh Uni had a shit ton of money – you didn’t own large swathes of property in a medieval city without making a few quid. And they were constantly throwing up new student flats to coin in more money. A lot of pomp and circumstance at official functions, yet students and staff got shafted. Before she started her PhD, Hannah had a notion of a future in academia, gentle research, corner office, funded conferences. But now, at the business end of her studies, she didn’t see it at all. But what else could she do with an astrophysics doctorate?

‘Kirsty.’ This was Rose speaking over Hannah’s shoulder.

Hannah turned and saw Kirsty with another woman she knew to be her wife, Mina. Both of them were tall up close, striking. Kirsty had a youthful glow, while Mina had a model’s cheekbones and air of confidence. They were a power couple for sure, Mina big in biotech.

Kirsty and Rose hugged, then Kirsty introduced Mina.

‘And this is Hannah Skelf, who I told you about,’ Rose said.

‘You did?’ Hannah said.

‘All good stuff, I promise.’ Kirsty’s accent made everything seem friendly.

‘I’m a huge fan.’ Hannah’s cheeks flushed. She felt like a wee girl with a pop star. ‘You’re an inspiration.’

Kirsty grinned and Hannah felt the full force of that smile, just for her.

‘Thinking of following in my footsteps?’

Hannah had imagined being an astronaut when she was younger, but that was silly, unrealistic. But Kirsty was standing here, another Scottish woman from an ordinary background. Why the hell not?

‘She could,’ Rose said. ‘She’s certainly smart enough.’

Hannah sipped her drink to hide her embarrassment and shook her head. ‘I don’t have the right stuff.’

Kirsty laughed, but not unkindly. ‘“The right stuff” is such alpha-male bullshit. It’s a twentieth-century mindset, men puffing their chests out to be the most heroic. I know you didn’t mean it like that, but the idea that only extraordinary people do this sort of thing is something I’ve struggled against my whole career.’

Mina leaned in with raised eyebrows. ‘You’ve touched a nerve.’

Kirsty nudged her wife and Mina spilled a little from her glass. They both smiled.

‘It’s about collaboration and community,’ Kirsty said. ‘Helping others. But you know that already, right? You’re kind of famous yourself, the Skelfs, private investigations and funerals.’

Hannah felt blood rise to her face again. She would never get used to the fact her family were famous in this town. Infamous, more like. Over the last few years, all the bullshit with her dad had been big news. How he murdered Hannah’s friend, Melanie. Escaped on the way to court, kidnapped Hannah’s half-sister Sophia, then been found and killed by Jenny. It was like a cheesy soap opera, except it was her life, trauma she had to come to terms with. It had taken time and understanding from Indy and others, but she finally felt on an even keel.

‘Sorry,’ Kirsty said, seeing her reaction. ‘I didn’t mean to be flippant about what you’ve gone through.’

Hannah shook her head and took another drink. The noise of the crowd swamped over her. Somewhere down in the street, a police siren wailed.

‘Not at all, it’s fine.’

Mina touched Kirsty’s arm, reminding her of something.

Kirsty cleared her throat. ‘But you’re an investigator, right? You find things out for people.’

‘I help when I can.’

Kirsty side-eyed Mina and clinked her wedding ring on her champagne flute. ‘I might need your help.’

Hannah thought back to earlier in the auditorium. ‘Is this to do with the heckler?’

‘Not exactly.’

She shared another look with Mina, then glanced around the room. Hannah followed her gaze, half expecting the same mouthy idiot to appear, pointing and shouting. People were looking at Kirsty while pretending not to, that famous-person-in-the-room vibe. One woman wearing a museum name badge stared. It must be weird to be so well known.

‘Maybe this isn’t the best place to discuss it.’ Kirsty handed Hannah a card with her address on it. ‘Why don’t you come to ours for dinner tomorrow?’

Hannah looked from Kirsty to Mina, who nodded.

‘I’d love to.’

7

Jenny

Jenny watched her mum take the veggie lasagne out the oven. Dorothy touched the small of her back once she’d put the hot dish on the table and straightened up. Just a twinge from age. Jenny thought of Violet, unable to take a drink without help. She was only three years older than Dorothy, fit as a fiddle a year ago.

Jenny lifted bowls of salad and garlic bread to the table as Hannah and Indy arranged cutlery, glasses, a jug of water and a bottle of Rioja. Her daughter was happy, healthy, hopelessly in love, lucky to find a soulmate so early in life. Jenny wondered if Dorothy considered Jim her soulmate. They’d been married for fifty years, so what else? Dorothy had Thomas now, a second chance at love, they obviously cared deeply for each other. Jenny wondered if she would ever have that again in her life. The one time she’d felt it, it was destroyed so brutally.

Dorothy dished up lasagne as Indy poured wine. Dorothy always tried to get them together for an evening meal. It started when Jim died, company to banish the grief, but had turned into something more, the glue between them. When Jenny was a young mum with Hannah, there was a lot of bullshit parenting advice about ‘quality time’. But there was no such thing as quality time, just time. Just be there, that’s your fucking job.

Jenny wondered if Hannah needed her anymore. She had Indy, and a close connection to Dorothy, two spiritual souls with a wider vision of the universe. Jenny felt like a Neanderthal next to them, but maybe she was being hard on herself. She was here, wasn’t she?