7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

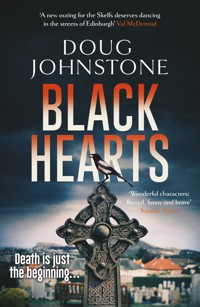

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

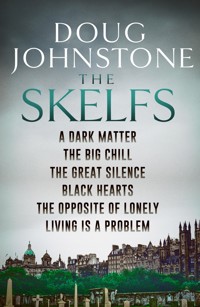

- Serie: The Skelfs

- Sprache: Englisch

A faked death, an obsessive stalker, an old man claiming he's being abused by the ghost of his late wife, and a devastating spectre from the past. The Skelfs are back in another warmly funny, explosive thriller, and this time things are more than personal… **SHORTLISTED for Theakston Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year** `A new outing for the Skelfs deserves dancing in the streets of Edinburgh´ Val McDermid `Tense, funny and deeply moving´ Mark Billingham `An engrossing and beautifully written tale that bears all the Doug Johnstone hallmarks in its warmth and darkly comic undertones´ Herald Scotland `A total delight to be returned to the dark, funny, compulsive world of the Skelfs … Johnstone never fails to entertain whilst packing a serious emotional punch. Brilliant!´ Gytha Lodge ___________________________ Death is just the beginning… The Skelf women live in the shadow of death every day, running the family funeral directors and private investigator business in Edinburgh. But now their own grief interwines with that of their clients, as they are left reeling by shocking past events. A fist-fight by an open grave leads Dorothy to investigate the possibility of a faked death, while a young woman's obsession with Hannah threatens her relationship with Indy and puts them both in mortal danger. An elderly man claims he's being abused by the ghost of his late wife, while ghosts of another kind come back to haunt Jenny from the grave … pushing her to breaking point. As the Skelfs struggle with increasingly unnerving cases and chilling danger lurks close to home, it becomes clear that grief, in all its forms, can be deadly… ___________________________ `The Skelfs keep getting better and better. Compelling and compassionate characters, with a dash of physics and philosophy thrown in´ Ambrose Parry `Expertly written, with poise, insight and compassion´ Mary Paulson-Ellis `If you loved Iain Banks, you'll devour the Skelfs series´ Erin Kelly 'Dynamic and poignant … Johnstone balances the cosmos, music, death and life, and wraps it all in a compelling mystery´ Marni Graff Praise for The Skelfs series ***Shortlisted for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Book of the Year*** ***Shortlisted for Theakston Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year*** ***Shortlisted for Amazon Publishing Capital Crime Thriller of the Year*** `Hurroo! The Skelfs — Edinburgh funeral directors and part-time private eyes — are back … the persistence of love in the Skelf household, no matter what fate flings at it, is reassuring and life-affirming´ The Times Book of the Month `Told with a wry humour and affection, the novel underlines just how accomplished Johnstone has become´ Daily Mail `Some of the most unique characters in crime fiction´ Daily Express `This enjoyable mystery is also a touching and often funny portrayal of grief ... more, please´ Guardian `Wonderful characters: flawed, funny and brave´ Sunday Times `Exceptional … a must for those seeking strong, authentic, intelligent female protagonists´ Publishers Weekly `Gripping and blackly humorous´ Observer `A tense ride strong, believable characters´ Big Issue `The power of this book, though, lies in the warm personalities and dark humour of the Skelfs, and by the end readers will be just as interested in their relationships with each other as the mysteries they are trying to solve´ Scotsman `Remarkable´ Sunday Times `Keeps you hungry from page to page. A crime reader can't ask anything more´ Sun `A thrilling, atmospheric book, set in the dark streets of Edinburgh. Move over Ian Rankin, Doug Johnstone is coming through!´ Kate Rhodes `An unstoppable, thrilling, bullet train of a book that cleverly weaves in family and intrigue, and has real emotional impact. I totally loved it´ Helen Fields

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 352

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR THE SKELFS

‘The Skelfs return in a dynamic and poignant entry in this startling series, where Johnstone balances the cosmos, music, death and life, and wraps it all in a compelling story featuring strong women’ Marni Graff

‘I am running out of superlatives for this cracking, unmissable series. I adore the Skelfs, am an unashamed #Skelfaholic (I even have the T-shirt). Black Hearts is outstanding. I loved it with a passion … best yet in this superb series’ Live & Deadly

‘A study in humanity from the darkest of corners’ Sarah Sultoon

‘Simply stunning. Tense, funny and deeply moving’ Mark Billingham

‘If you loved Iain Banks, you’ll devour the Skelfs series’ Erin Kelly

‘Nobody portrays modern Edinburgh better than Doug Johnstone. The Great Silence speaks volumes about the power of story’ Val McDermid

‘Mysteries aplenty … a poignant reflection on grief and the potential for healing that lies within us all. A proper treat’ Mary Paulson-Ellis

‘A thrilling, atmospheric book, set in the dark streets of Edinburgh. That great city really came alive for me in this gripping tale. Move over Ian Rankin, Doug Johnstone is coming through!’ Kate Rhodes

‘An unstoppable, thrilling, bullet train of a book that cleverly weaves in family and intrigue, and has real emotional impact. I totally loved it’ Helen Fields

‘The power of this book, though, lies in the warm personalities and dark humour of the Skelfs, and by the end readers will be just as interested in their relationships with each other as the mysteries they are trying to solve’ Scotsman

‘Remarkable’ Sunday Times Crime Club STAR PICK

‘Keeps you hungry from page to page. A crime reader can’t ask anything more’ The Sun

‘This enjoyable mystery is also a touching and often funny portrayal of grief … more, please’ Guardian

‘Wonderful characters: flawed, funny and brave’ Sunday Times

‘Exceptional … a must for those seeking strong, authentic, intelligent female protagonists’ Publishers Weekly

‘An engrossing and beautifully written tale that bears all the Doug Johnstone hallmarks in its warmth and darkly comic undertones’ Herald Scotland

‘Gripping and blackly humorous’ Observer

‘A tense ride … strong, believable characters’ Kerry Hudson, Big Issue

SHORTLISTED for the McIlvanney Prize for Best Scottish Crime Book of the Year

LONGLISTED for Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year

SHORTLISTED for Amazon Publishing Capital Crime Thriller of the Year

Black Hearts

Doug Johnstone

For Tricia, Aidan and Amber

Contents

Black Hearts

1

Dorothy

The atmosphere in Liberton Cemetery was off. Dorothy pulled at her cuffs as she walked behind the four pallbearers carrying Kathleen Frame to her last resting place. The starchy Church of Scotland minister had just finished an awkward service in the kirk behind them, and that energy followed them out to the graveyard. With the stone steps and rough tarmac here, they couldn’t use the wheel bier. It wasn’t good to have the coffin rattling its way to the grave, mourners imagining the body being tossed around inside.

Archie was front left of the coffin, holding a handle at waist height. Across from him was Mike, Kathleen’s brother-in-law, mouth turned down. Back left was Kathleen’s son Danny, gripping his handle so tight his knuckles looked fit to burst. He glowered at Mike’s back like he was trying to burn a hole through him.

Grief came in infinite forms, there were as many different ways to mourn as there were people, and Dorothy had learned never to be surprised. Some wailed and gnashed their teeth, others quietly sobbed, laughed nervously or openly, stood like statues, simmered like pressure cookers.

They passed a row of old, fallen gravestones, no living relatives to pay for restoration. They walked past a gathering of smaller graves for stillborn babies, all from the early seventies. She thought about the lost possibilities. They would be late forties now, her daughter’s age.

The pallbearers walked through a passageway in the wall separating the old kirkyard from the newer cemetery. The view from Liberton Brae filled Dorothy’s heart, Arthur’s Seat and Salisbury Crags towering over the city like ancient sentinels. She could see the observatory on Blackford Hill where Hannah’s post-grad office was, and Braid Hills further left, large expanses of grass and gorse.

The sky was mottled salmon skin, the leaves on the cherry and yew trees wet to touch as Dorothy passed. She felt the freshness on her fingers, touched them to her forehead. Up ahead, Danny was still trying to crush his coffin handle, staring at Mike’s back. The fourth pallbearer was a friend of Danny’s called Evan, clearly uncomfortable in a black suit too small for his lanky frame. He’d accompanied Danny to the Skelf house to arrange the funeral. Danny didn’t mention his dad throughout the whole process.

As they came over the rise, the view of the city expanded. Dorothy thought about her family’s relationship with Edinburgh. She pictured the city as a biodome, a complex and interconnected group of organisms, autonomous yet part of a greater self. She imagined herself, Jenny, Hannah and Indy as miniscule bacteria, working to help other parts of the whole, scurrying from their funeral-director home to hospitals, care homes, hospices, the mortuary, churches, mosques, synagogues, crematoriums, cemeteries, graveyards, memorial gardens, wakes. Helping people transition from life to death.

She looked around. There were thirty mourners, mostly middle-aged, a handful of Danny’s friends, wide-eyed at being confronted by mortality. Graveyards were no place for the young.

They walked past a noticeboard at the Liberton Brae entrance. Pinned on it was a council warning not to misbehave, sixteen bullet points written in constipated quasi-legal language: ‘No person shall, whilst in a cemetery, wilfully or carelessly use any profane or offensive language, or behave in an offensive, disorderly or insulting manner.’

‘Fuck off,’ Dorothy said under her breath.

They reached the freshly dug grave and put Kathleen down on a low wooden plinth alongside. Archie joined Dorothy as the mourners gathered at the other side of the grave. The smell of damp earth was strong, and Dorothy thought of planting and rebirth. She was spiritual not religious, didn’t follow any doctrine but did believe there were energies in the universe we don’t fully understand. Hannah told her that modern physics agreed – the interconnectedness of things, chaos theory, fuzzy logic, quantum entanglement.

She looked at the coffin and the grave. Burial was becoming less common, cremation overtaking. Both were terrible for the environment, but most people they dealt with were old and liked the old ways. Things take time to change.

The minister stood at the head of the grave. Danny glared at his uncle, who stood next to his wife. Mike had a strong jaw and blue eyes, Roxanne had bright-red hair, Jackie O shades and a low-cut black dress.

Dorothy glanced at the adjacent gravestone, worked out the age of William Hush when he died. Sixty-seven. She did this with every grave. Now, at seventy-two, she was older than many she calculated.

The minister’s monotone fought with the traffic noise from Liberton Brae. A bus’s chugging engine filled the air. Two crows took off from a gravestone and flew into a fir tree. Dorothy felt drops of rain on her face.

‘You fucking know.’ This was Danny pointing at Mike.

Evan reached for Danny’s shoulder but Danny shook him off. The minister stopped.

Danny took two steps towards Mike. ‘You know where he is.’

Mike shook his head and took his hands out of his pockets.

‘Danny,’ he said. ‘He’s gone.’

‘No.’ Danny took more steps. ‘He faked the whole thing and you know all about it.’

‘You’re wrong.’ Mike’s fists were clenched. He shifted his shoulders so that he was now protecting Roxanne.

‘You bastard.’

Danny lunged at him. Mike ducked but not quick enough, got a thunk on the side of his head which knocked him off balance. Danny shoved his chest and kicked his crotch, Mike doubled over. Danny went to punch again but Mike shoulder-charged him, arms around his waist as they staggered towards the open grave. Danny smacked the back of Mike’s head then writhed free and spun the pair of them round. Mike’s heels hung over the lip of the hole as Danny pummelled him. They lurched backward and for a moment they were suspended over the grave. Mike’s feet scrambled until he found footing on the other edge of the grave, Danny gripping his waist, their weight propelling them over the hole and straight into Kathleen’s coffin, which slid off the plinth and smacked into William Hush’s gravestone. The lid split as the casket fell back from the stone, then it flapped open and Kathleen sprawled onto the grass, her face thumping the ground, skirt riding up her thighs, arms splayed out like she was skydiving.

2

Jenny

She stepped into the water and her breath caught in her chest. She waded deeper, grey swells hitting her thighs and groin. She breathed, tried to get over the shock. Each time she did this, her body acted like it would never recover. Gradually her breathing softened but her skin still burned with cold. She went in up to her chest and turned.

Porty Beach had changed a lot in the few years since she’d lived down here. It was mostly empty back then and no one went wild swimming. She hated that term, it was just swimming. Now groups of women were out in the water, bathing-capped heads bobbing like inquisitive seals along the seafront. Some folk were on paddleboards, kayaks, a rowing boat heading to Musselburgh. The sky reflected the shifting grey of the sea.

She swam straight out. Most other swimmers were in groups, but she wasn’t someone who joined in. The dark stretch of Fife lay across the firth as she swam into bigger waves, salty mouthfuls when she timed it wrong, seaweed against her legs. It wouldn’t take Freud to work this out. Just over a year since all the shit with Craig on Elie beach – setting fire to him and watching him burn on the boat like it was a Viking funeral. They still hadn’t found his body. And here she was, swimming in the same stretch of water to heal herself mentally and physically. And maybe stumble across his charred and bloated corpse so she could be sure.

The waves got bigger as she paused to rest. Swirls tugged at her legs, an undertow she hadn’t felt before, despite coming here for the last year. Brandon, her therapist, had his doubts about all this. Dorothy and Hannah pushed her towards therapy because of the night terrors, the alcohol and sleeping pills, the fact she’d destroyed everything with Liam. Fuck, swimming was supposed to stop her thinking.

She pushed into the swells, sea spray on her face. She felt another tug at her legs as a wave swept over her. She flipped, struggled to get upright, eyes stinging from the salt. She saw gloomy daylight for a moment, gulped in air, then another wave crashed on her head, pushing her under like a giant hand, the undertow spinning her until she wasn’t sure which way was up. She felt another wave hammering the surface and plunging through to shove her down, her lungs starting to burn, arms and legs frantic, scrambling to get to the surface, whichever way that was, then another wave and she felt energy drain from her limbs.

She saw a figure approach through the murk, then she was spun around by a current. She felt hands on her waist, pushing her up, and she pictured Craig, his gun at her head as he shoved her into the boat and poured petrol over her before she flipped things and sent him to his death. But maybe he had come back, this was his revenge, drag her to the bottom of the ocean with him.

Her head broke the surface and she gasped, swung round and threw a punch, only it wasn’t Craig, of course, just some Good Samaritan saving her life, blood now pouring from his nose. A wave broke over her head and she wanted to get sucked into oblivion.

‘So that’s been my morning,’ Jenny laughed. ‘Punched a guy for saving my life. What about you, cured any psychos?’

She tilted her head and smiled at Brandon. His office was just big enough for a desk in one corner, a therapy area in the other, two low chairs facing each other. The chairs were uncomfortable and Jenny heaved herself out and walked around. Nervous energy coursed through her every time she came here.

Brandon King was attached to the university’s psychology department. He wasn’t a qualified psychotherapist yet, which meant he was dirt cheap. His wee office in the new building at the bottom of Chalmers Street was a stone’s throw from where Hannah used to attend counselling sessions. Hannah had apparently come to terms with her dad’s psychotic behaviour and eventual death. She had Indy for support, a new marriage to a loving wife, two beautiful young things bouncing back from everything life threw at them. Jenny didn’t feel like she would ever bounce back from this.

She stared out of the window. The leaves were turning in the Meadows and over on Bruntsfield Links. She could just see their house, three storeys of Gothic Victorian melodrama overlooking the Links from Greenhill Gardens. Funeral directors and private investigators, it was a wonder she hadn’t been to therapy before now. And she didn’t even believe in therapy. Talking about your feelings was stupid. She’d come here under duress but found Brandon cute and amiable, a daft puppy.

She turned back to him. He still hadn’t spoken, classic therapist schtick. He was tall and goofy, a mop of curly black hair, in a plaid shirt and jeans, Converse. He was early thirties, not quite young enough to be her son but not far off.

He stuck his chin out eventually. ‘So how did that make you feel?’

Jenny rolled her eyes and tutted at the cliché. ‘Fucking great. I’ll be lucky if he doesn’t sue.’

Brandon nodded. ‘Are you sure swimming in the Forth is a good idea?’

He was a hundred-percent right. But imagine a crazy coincidence, if, one time, she found Craig’s disintegrating corpse bobbing on the surface, fish nibbling his toes, sucking out his eyeballs, chewing on his rectum. How fucking sweet would that be?

‘It’s good exercise,’ she said.

Brandon frowned. She found his disapproval hilarious. He knew exactly what she was like yet still managed to be disappointed in her.

‘What about the meditation exercises we talked about?’

She went cross-eyed and stuck her thumbs up. ‘Just great. Fantastic.’

She was trying to get a rise out of him, part of the playful back and forth.

He shrugged and smiled. It was a cute smile. ‘You’re paying for these sessions, Jenny. If you don’t think they’re useful…’

This was part of it too, he pretended he didn’t care but he was too nice not to.

‘OK.’ Jenny put her hands up as if he was pointing a gun. She remembered Craig doing exactly that on Elie beach, lighthouse flashing behind him, the shush of the waves in her ears.

She felt suddenly tired, crashing after the adrenaline from the thing in the sea earlier.

Her phone pinged in her bag, and she went to her chair and took it out. A message from Mum. She read it and lifted her bag from the back of the chair, threw it over her shoulder and stuffed the phone back in.

‘Sorry, big guy, I have to pick up a body. You can cure me next time.’

3

Hannah

Hannah watched Indy walk up Middle Meadow Walk towards Söderberg. Her hair had grown out recently and suited her face, and the dark-turquoise highlights matched her eyes. The curve of her hips in her suit, bracelets on her wrists, henna patterns on her hands. She spotted Hannah and waved. Hannah got up from her seat outside the café and they kissed, once hard then a softer coda.

‘How’s work?’ Hannah said as they sat.

‘You know,’ Indy said, flicking her hair forward over a shoulder. ‘Full of death and grief. You didn’t make it into uni yet, then?’

‘Not quite.’

Hannah had been excited to start her PhD a year ago, working in the exoplanet research group at Edinburgh University, her own small office at the Royal Observatory. But she was in the middle of it now and felt a little ground down. She was a long way from the initial burst of enthusiasm, but the end point seemed an impossible goal. Her daily routine was number crunching and mathematical modelling, working out the signatures of planets around other stars. But the giant telescopes they needed to detect these things took forever to come online, and it all seemed billions of miles away. Literally.

A waitress took their order, salmon on rye for Hannah, halloumi salad for Indy. They swapped small talk about Indy’s work. She still sometimes covered the phones at the Skelf house, but she’d progressed to being a funeral director now, dealing with everything from the bodies to the ceremony, the technicalities to aftercare. It was like being a wedding planner except you had to do everything in a week, at a time when your clients were distraught and fragile.

Hannah helped out between studies, but she preferred to work the PI stuff. At the moment she had plenty of time.

Indy had been talking and she’d drifted off.

‘What?’

Indy cricked her neck. ‘You weren’t listening.’

‘Sorry.’ Hannah reached for her hand. Her fingers ran over Indy’s engagement and wedding rings.

‘I said you need to find that spark again,’ Indy said. ‘Remember how excited you were when you started your postgrad? Kid in a sweet shop.’

Hannah shrugged. ‘We all grow up.’

Indy gave her a wide-eyed stare. ‘Shit, it’s worse than I thought. You’re only twenty-three.’

Hannah looked at the path alongside, from the Old Town to the Meadows. An artery full of people, lots of students now that classes were back, fewer tourists since the festival had packed up, and, in between, all the variety that Edinburgh had to offer – young mums, old couples, teenagers bunking school, skateboarders, cyclists, dropouts, office workers. Every one of these people was a newborn baby once. Each of them shaped by countless forces, kind parents and bullies, accidents and bad decisions, good fortune and determination. An infinite interplay that you could never model on a computer. And they would all end up as corpses. The best we could hope for was to live a decent life and that someone might miss us a little when we’re gone.

Hannah laughed.

‘What?’ Indy said.

Hannah shook her head and squeezed Indy’s hand. ‘Just happy to be alive.’

That was a catchphrase between them, a signal when either of them went dark in their minds. It started as a joke but it felt deeper now.

Their food arrived and they ate. Hannah felt a smirr of rain from the heavy sky, saw the trees sway in the wind.

Indy took a mouthful of salad. ‘Hey, Nana called this morning.’

‘Everything OK?’

‘Just wanted a blether.’

This was Indy’s gran, Esha, who’d come over last year from Kolkata with husband Ravi. She liked to keep tabs on Indy and Hannah’s exotic lesbian marriage – in an approving manner. Hannah loved that Indy was close to her grandparents, they were all the family she had. She thought about her own mum and gran living together in a house ten minutes from her flat.

A middle-aged woman walked up the lane with an elderly man. He had a cane and waved her away as she fussed over him. Hannah flashed on Dorothy on a metal table in the embalming room and felt her throat tighten. Dark thoughts, just happy to be alive.

‘We really should go visit Esha and Ravi,’ Hannah said.

Unspoken between them: before it’s too late.

Indy nodded. ‘Kolkata would blow your mind.’

‘Hi.’

Hannah turned at the voice behind her, saw a woman her own age, small and thin, hair in a messy bun, hoop earrings, large round glasses and a wide smile. She wore a flouncy white blouse and a hippyish brown leather jacket, leggings and trainers.

‘Hi,’ Hannah said, a question in her tone.

‘Sorry, you must think I’m so rude, interrupting your lunch.’ The woman glanced at the plates, then at Indy, then Hannah. ‘I’m Laura, we actually met once but you won’t remember.’

She left a pause and Hannah tried to think.

Laura shook her head as if reprimanding herself. ‘Laura Abbott, I study physics at King’s Buildings, final year of undergrad. You did a talk about postgrad opportunities, I asked about mentors.’

That rang a vague bell. ‘I remember, hi.’

Laura nodded, making her earrings bump against her jutting collarbone. ‘Anyway, I just spotted you, thought I would say hello.’

Laura looked at Indy, who smiled warmly.

Hannah took the hint. ‘This is my wife, Indy.’

‘Your wife, that’s so cool.’ Laura seemed surprised she’d said that out loud and raised two fingers to her lips. ‘Sorry.’

Indy smiled at Hannah. ‘Not at all, it is cool.’

Laura leaned in and glanced over her shoulder like she was about to tell a secret. ‘I hope this isn’t weird, but I just wanted to say you’re a bit of an inspiration.’

Hannah felt a shiver run through her.

‘I mean, everything you went through.’ She glanced at Indy, back at Hannah. ‘With your dad.’

Hannah straightened her shoulders and pushed her chin out. Her family history had been big news over the last few years, of course strangers would know.

Laura spotted the body language and recoiled, stumbled over the kerb. ‘I’m so sorry, I shouldn’t have said anything.’

‘It’s fine.’

Hannah listened to the chatter from nearby diners, a clatter of cutlery, the coo of a woodpigeon in the oak tree.

‘I should…’ Laura pointed a thumb down the road. ‘I just … I’m sorry.’

Hannah shook her head. ‘It’s fine, Laura, honestly. It was good to meet you.’

Laura switched on a smile. ‘OK. Bye.’

‘Bye.’

Indy waved after her. ‘Bye, Laura.’ She turned to Hannah with a grin. ‘Somebody has a crush on you.’

‘Shut up.’ Hannah watched Laura walk away and tried to remember, but she was pretty sure she’d never seen her before in her life.

4

Dorothy

Leslie’s Bar was the kind of old-school pub that was vanishing from Edinburgh. Carved wooden gantry, stained glass and burgundy upholstery. Dorothy sat with Danny Frame in the snug, separated by more dark wood and glass from the main bar where the wake was happening. The noise of reminiscing and condolence drifted over the divider as Dorothy sipped her Lagavulin and felt the peaty burn. Danny glugged a pint of cloudy IPA, took off his black-framed glasses and ran his thumb and finger across his eyes.

‘Takotsubo,’ he said, putting his glasses back on.

‘Sorry?’

Danny drank, nodded to himself. ‘Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, that’s what they said Mum died of. It’s like a heart attack except there’s no obvious clinical cause. The left ventricle balloons up. That’s how it gets its name, it looks like a pot used by Japanese fishermen to trap octopuses.’

He touched a hand to his chest and held Dorothy’s gaze. ‘Also known as broken-heart syndrome. Brought on by extreme emotional distress. I Googled it.’

‘I’m sorry.’ Dorothy examined Danny – young, smart, desperately lost.

She was a little surprised the wake had gone ahead. After Kathleen’s body had tumbled from the coffin, Danny and Mike separated and sat getting their breaths back. Archie and Dorothy hurried over to sort the casket, lifted Kathleen in with as much decorum as they could muster, then secured the lid. What a clusterfuck. Hard for Danny to see his mum like that. The rest of the ceremony went off quietly, just the minister’s religious murmur drifting through the air.

Dorothy heard a laugh from the other side of the pub. People should laugh at a wake, remember the good times. But Danny scowled at the wall and gulped more IPA. He waved a hand at Dorothy.

‘I owe you an explanation.’

Dorothy sipped her whisky. ‘You don’t owe anyone anything. You just buried your mother.’

His face crumpled. He ran his tongue around his lips. ‘That bastard.’

Dorothy knew it was often best to let people talk it out. That carried over to the investigator business, where people would give themselves away if you left enough silence.

Danny straightened his shoulders. ‘So. My dad went missing a month ago.’

So that was why Danny hadn’t mentioned him while arranging Kathleen’s funeral.

‘His car was found next to Seacliff Beach in East Lothian. He told Mum he was going stand-up paddleboarding. He had his wetsuit. He was spotted going into the water by some horse riders on the beach. His clothes were at the car. No sign of the board or paddle. Just vanished on a calm day.’

It was clear from his tone what Danny thought of that.

‘The police think he got into difficulties. There are weird tides, he got sucked under.’

Dorothy sipped her whisky. A voice floated over the divider, telling an anecdote or joke. ‘But you don’t think so.’

Danny snorted and gulped his pint. ‘No chance. He’s experienced, a good swimmer. If he died, where’s the body?’

‘Washed out to sea?’

‘I spoke to a coastguard guy. He said bodies usually wash up in the few days after. Think of all the people who jump off the Forth Road Bridge. They find almost all of them.’

‘That’s more built up. And it’s in the narrow part of the firth. Seacliff is almost open sea.’

Danny stuck his bottom lip out. ‘He’s not fucking dead.’

Dorothy looked at him. Denial was human nature, the first part of grieving according to theory, followed by anger. Danny seemed halfway between the two. Not that the theory stood up. Dorothy had dealt with more grief than she could comprehend in the funeral business and it didn’t follow a nice, easy pattern.

Danny lowered his head. ‘Shit, I can’t believe we did that at Mum’s funeral.’

‘Don’t be too hard on yourself. You’re under a lot of stress.’

‘She would’ve found it pretty funny, she had a fucked-up sense of humour.’

Dorothy smoothed her skirt, rested her hands on her knees.

Danny looked at her. ‘She was convinced something happened to him, he was carried out to sea and drowned. She wouldn’t entertain the idea he might’ve faked it. I hinted at it once and she shut me down. Said he wouldn’t do that.’

He puffed his cheeks and breathed out. Took a big slug of beer. ‘I don’t know about breaking her heart, but it definitely killed her. There’s scientific evidence that grief makes you physically weak. You hear about couples where one dies not long after the other. Mourning is stressful, gives you high blood pressure, blood clots, reduces your immune system.’

Dorothy knew that from the funerals and her own grief. When Jim died she felt sick, didn’t eat, drank too much, threw herself into crazy situations to cope. She always hated that phrase, ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’. Bullshit. What doesn’t kill you can make you weak, can destroy you in a million different ways. Can make your existence miserable.

Danny finished his pint.

Dorothy understood his need for oblivion right now. ‘So that’s what the fight was about?’

‘Uncle Mike is Dad’s brother. They’re pretty close. I’m sure he knows something. He acted weird when Dad went missing, like he didn’t give a shit.’

Dorothy finished her whisky, felt the stickiness on the glass as she placed it on the table. She could smell the stale booze of the drip trays and a hundred years of drowned sorrows from the bar. ‘Plenty of middle-aged men don’t show their emotions. It’s a badge of honour.’

Danny ran a hand through his hair. ‘This is different.’ He rubbed at his neck. ‘You lot investigate stuff, right? As well as doing the funerals.’

It wasn’t exactly a secret in a small city like Edinburgh. They took cases when they felt right, and sometimes when they felt wrong but needed to be done. This felt right to Dorothy.

‘We do.’

Danny’s eyes looked sharper suddenly. ‘I want you to find my lying piece-of-shit dad. Will you help?’

Dorothy took him in. Already so much on his shoulders. One parent fresh in the grave, the other lost at sea. Or maybe not. Either way, he needed help.

Another ripple of laughter came from the other side of the bar.

‘Of course,’ she said, and went to buy another round.

5

Jenny

Indy drove the body van southeast towards the Royal Infirmary while Jenny stared out of the window at the ghosts. If you lived somewhere all your life, memories haunted you at every corner. They turned at Grange Cemetery, where Jenny picked up a PI case from oddball twins a year ago. They drove past The Old Bell, where Jenny remembered flirting with Craig early in their romance. If she’d known how things would turn out, she would’ve run a mile. But then she wouldn’t have Hannah, so no. They hit the roundabout at the Cameron Toll shopping centre, where Jenny lost Hannah for a heart-bursting fifteen minutes when she was a toddler. Her cheeks flushed thinking about it now, the kind old man who found her in Waterstones reading a kids’ book about the solar system.

‘How’s therapy going?’ Indy said.

Jenny turned. Indy never seemed to do chitchat with her. Those eyes always looked into Jenny’s soul, uncomfortable but weirdly reassuring. Jenny was glad she had this relationship with her daughter-in-law, although that meant she was a mother-in-law and fuck that shit.

‘Happier and healthier every day.’ Her voice rose at the end and she sounded manic, kind of on purpose but also not.

‘I know you don’t believe in it,’ Indy said. ‘But Hannah appreciates you trying. We all do.’

Jenny swallowed. Christ, how did a woman in her twenties who’d cremated her own parents get to be so smart?

‘It’s not that I don’t believe in it…’ Jenny didn’t know how to finish the sentence.

They hit roadworks on the A7 at the entrance to Craigmillar Castle Park Cemetery. The lights changed but the traffic didn’t move. Fucking Edinburgh.

Indy nodded at the cemetery entrance. ‘Got one in there soon. A toddler.’

‘Jesus.’

‘It’s tough.’

The engine idled, a lorry rumbled past the other way.

‘Did Dorothy tell you about my ideas for the business?’

Jenny shook her head.

‘I’m researching more eco-friendly funerals.’

‘Like Archie’s mum in Binning Wood?’

‘That’s one option. I mean, I love this work but did you ever stop to think what we’re doing?’

Jenny scrunched up her face. ‘I try not to.’

Indy waved her hands above the steering wheel. ‘We’re either pumping bodies full of embalming chemicals then throwing them in the ground to poison the earth, or we’re setting fire to them, using up tons of energy and generating a shitload of carbon dioxide. We’re in the middle of a climate catastrophe and our carbon footprint is terrible.’

Jenny felt guilty that she hadn’t thought about it more. Hannah and Indy’s generation took the climate crisis more seriously, for obvious reasons.

‘What else is there?’

The traffic moved and they edged forward, almost at the lights when they changed back.

‘Natural burial with no embalming, for a start. And there’s a company doing human composting, you can use your remains to grow trees or vegetables.’

Jenny stuck out her bottom lip. ‘I think some of our older punters might baulk at that.’

Indy nodded. ‘We have to keep the old options on the table, but things need to change. There’s promession, which is freeze drying and shaking to bits, but that’s not well developed yet. Or you can get buried in a mushroom suit.’

Indy got her phone out and searched, showed Jenny a picture of a small Asian woman giving a TED talk, in a black outfit covered in white lines branching like lightning strikes.

‘It’s covered in spores that digest your body in the ground, neutralising harmful stuff like pesticides, medicines, heavy metals.’

‘Heavy metals?’

‘The average cremation releases four grams of mercury into the air, from fillings and other stuff. It’s crazy. And now they’re finding microplastics in corpses.’

‘We are so fucked.’

The traffic light turned green and they were through. Jenny was suddenly aware of the car fumes around them.

‘We can do better.’ Indy’s voice was soft and upbeat, as always. ‘Environmental doomism is not the answer. It’s fixable.’

‘With a mushroom suit.’

‘It’s a start.’

They turned into the RIE site, negotiated more building work and closed lanes, then drove to the back of the main building. The mortuary had its own entrance, away from the living. Indy parked and they took the gurney out the back, telescoped the legs and wheeled it to the entrance. Indy buzzed and they were let in, met by a young woman in scrubs with Nancy on her nametag.

Nancy and Indy chatted, so maybe it was only with Jenny that Indy didn’t do small talk. We’re all different versions of ourselves with different people. She thought about herself as a mother, daughter, ex-wife, middle-aged woman full of anger.

‘Rhona Wilding,’ Nancy said, opening one of the doors on the huge wall of body fridges. So much space for dead people in a hospital. ‘Born sixth of January, 1977.’

Shit, two years younger than Jenny.

Indy pulled on blue nitrile gloves from a box on the desk and unzipped the body bag down to Rhona’s chest. She had black hair that needed washing, blue lips, small nose. Indy checked for jewellery, compared Rhona’s face to a picture on her phone. ‘Visually confirmed.’

They’d never picked up the wrong person before, but this procedure had saved them a couple of times from making that mistake. There were a lot of corpses in the world.

Jenny looked around the room. No windows, a yellow tinge to the artificial light. A desk and a computer. Could’ve been any office in the city, except for the fifty fridges and a huddle of gurneys cowering in the corner.

‘How did she die?’ she said.

Nancy snapped off her gloves, balled them and threw them in the bin like a pro. ‘Stomach cancer. Ate her up from the inside.’

Jenny breathed out as she thought about that.

‘Come on,’ Indy said gently.

Jenny put on gloves too and took Rhona’s legs, Indy behind her shoulders. Indy counted to three and they lifted her from the tray to the gurney, strapped her in. Indy signed some paperwork and they were out into daylight, wheeling Rhona to the van, sliding her inside. The whole visit took ten minutes.

Back on the road, they turned left out of Little France to avoid the roadworks, drove through Craigour and Moredun, turned north towards The Inch. Jenny didn’t know this road well, her only reference was that Mount Vernon and Liberton Cemeteries were over to her right. She wondered how Mum and Archie got on at the service this morning.

‘But the most promising eco-funeral tech is resomation,’ Indy said, as if they’d never stopped talking about it. ‘I think we should buy a Resomator S750. They’re expensive, but it’s an investment. Water cremation, you stick the body in a boiling water-and-alkaline solution, it dissolves in a few hours. The water can be used as fertiliser or cleaned in standard water treatment plants, and they dry out the remains so you still get ashes. It uses a fifth of the energy and produces no greenhouse gases. It’s miles better for the planet.’

‘Not sure about pumping human remains into the ocean, Indy, I swim in there.’

Indy smiled as they turned past King’s Buildings up Esslemont Road towards home. ‘It’s cleaner than normal sewage. Besides, there must be millions of dead bodies in the world’s oceans already, and you’re happy to swim with them.’

Jenny imagined Craig’s corpse doing the front crawl, racing through the water towards her. They passed Grange Cemetery again and she wondered if she would ever escape the dead.

6

Dorothy

Dorothy put the large bowl of rice in the middle of the table. She went back to the big pot of veggie chilli on the stove and gave it a final stir. She turned and took a moment. Hannah, Indy and Jenny were fussing around the table, sorting out tortillas, guacamole and salsa, cutlery and plates. It made her heart swell. She tried to appreciate having these women in her house, but the moments always slipped away. She thought about the Buddhist idea of impermanence, how everything changes.

‘In one of your dwams, Mum?’ Jenny smiled at her. A running joke for decades, how Dorothy tended to fall away from what was happening, try to gain perspective. Jenny could never understand that mindfulness.

Dorothy took the chilli to the table. ‘How was therapy?’

Jenny made a face and Indy laughed. ‘Don’t, Indy already asked.’

Indy and Hannah’s flat was not far away and they ate here more often than not. Dorothy cooked to stop her house feeling empty since Jim died. Anything that kept these women in her life was worth it.

She remembered something and went to the large whiteboards on the wall. Rhona Wilding was now on the funeral board in Indy’s handwriting. She moved to the PI board, got a marker and wrote Eddie Frame in big letters.

Schrödinger came in and slinked around Dorothy’s legs. She bent and touched his back. He hadn’t been the same since their dog Einstein died, who knew a cat could give a shit? Dorothy remembered Einstein’s ravaged body on the funeral pyre in the back garden. That dog saved her life.

The cat walked over to the armchair by the window and Dorothy looked out. It was already dark, lights buzzing along the paths of Bruntsfield Links. The undulating grass looked like shifting dunes in the yellow light. Jim’s ashes were scattered out there, grains of him in worms and flowers, or floating in the air, circling the planet looking for a home.

‘I took a case today,’ she said, returning to the table.

The majority of cases were walk-ins or phone calls, but sometimes the funeral work brought a mystery to their door.

‘The same Frames as today’s funeral fight?’ Jenny said.

Archie had already got the rest of the women up to speed on this morning’s debacle.

Dorothy nodded.

Indy looked at the funeral board. ‘We buried Kathleen and Danny arranged it, so who’s Eddie?’

‘Danny’s dad,’ Dorothy said, spooning rice onto her plate. ‘He went missing while paddleboarding in East Lothian a month ago.’

Jenny frowned. ‘And his body never showed up?’

Dorothy shook her head and added chilli and guacamole to the rice.

‘Very Reggie Perrin,’ Jenny said.

Hannah threw Indy a look. ‘Who’s that?’

Jenny rolled her eyes.

Dorothy smiled. ‘A television comedy in the seventies, he faked his own death, left a pile of clothes on the beach and walked into the sea.’

Indy grinned. ‘The seventies were so weird.’

‘Seventies television made me who I am today,’ Jenny said. ‘Which explains a lot.’

Indy turned to Dorothy. ‘So Danny thinks he faked it?’

Dorothy forked chilli into her mouth. Not enough cumin. ‘He wants us to find Eddie, if he’s alive. The fight was between Danny and his Uncle Mike.’

‘Fucking men,’ Jenny said.

The anger in Jenny’s voice made Dorothy’s heart ache. She wanted her daughter to find peace but that seemed a long way off. Her instinct was to help but that closure had to come from within. All Dorothy could do was be here. It made her feel sick, if she was honest, but that was parenthood.

The house phone rang from out in the hall. The business was closed but they always picked up, it could be a grief-stricken relative, a body to pick up, someone in need.

Indy was already out of her seat, but Dorothy rose and waved her back to the table. ‘I’ll get it.’

She went to the hall and lifted the handset. This was connected to the line downstairs, their personal and business stuff tangled up forever.

‘The Skelfs, Dorothy speaking, how can I help?’

‘Yes, Mrs Skelf, I remember you.’

An old man, Asian accent. ‘Call me Dorothy, please.’

‘Very good. I am Udo Hayashi, do you remember me?’

Elderly Japanese gentleman, they cremated his wife a few months ago. She was Scottish, Dorothy pictured her name on the funeral board, Lily.

‘Of course, Mr Hayashi, I remember.’

‘Call me Udo. You helped with Lily, you were very kind.’