Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: SAMPI Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

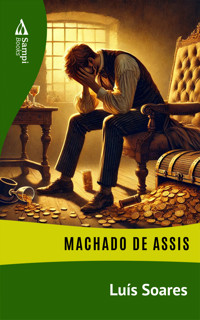

Luís Soares, an ambitious and gallant young man, lives between the pursuit of social status and the charms of love, but his lack of scruples leads him to betray friends and commitments. As his web of lies crumbles, he faces the consequences of his choices, culminating in a bitter personal decline.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 36

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Luís Soares

Machado de Assis

SYNOPSIS

Luís Soares, an ambitious and gallant young man, lives between the pursuit of social status and the charms of love, but his lack of scruples leads him to betray friends and commitments. As his web of lies crumbles, he faces the consequences of his choices, culminating in a bitter personal decline.

KEYWORDS

Ambition, betrayal, decadence

Notice

This text is a work in the public domain and reflects the norms, values and perspectives of its time. Some readers may find parts of this content offensive or disturbing, given evolving social norms and our collective understanding of issues of equality, human rights and mutual respect. We ask readers to approach this material with an understanding of the historical era in which it was written, recognizing that it may contain language, ideas or descriptions that are incompatible with today's ethical and moral standards.

Foreign language names will be preserved in their original form, without translation.

I

To exchange day for night, said Luís Soares, is to restore the empire of nature by correcting the work of society. The heat of the sun is telling men to rest and sleep, while the relative coolness of the night is the true season in which to live. Free in all my actions, I don't want to subject myself to the absurd law that society imposes on me: I'll watch at night, I'll sleep during the day.

Unlike many ministries, Soares carried out this program with a scrupulousness worthy of a great conscience. For him, dawn was twilight, twilight was dawn. He slept twelve consecutive hours during the day, from six in the morning to six in the evening. He ate lunch at seven and dinner at two in the morning. He didn't have supper. His supper was limited to a cup of chocolate that the servant gave him at five o'clock in the morning when he entered the house. Soares swallowed the chocolate, smoked two cigars, made a few puns with the servant, read a page of some novel, and went to bed.

He didn't read newspapers. He thought a newspaper was the most useless thing in the world, after the Chamber of Deputies, the works of poets and masses. This is not to say that Soares was an atheist when it came to religion, politics and poetry. No. Soares was simply indifferent. He looked at all the great things with the same face as an ugly woman. He could become a great pervert; until then he was just a great uselessness.

Thanks to the good fortune left to him by his father, Soares was able to enjoy the life he led, shirking all kinds of work and giving himself over only to the instincts of his nature and the whims of his heart. Heart is perhaps too much. It was doubtful that Soares had one. He said so himself. When a lady asked him to love her, Soares would reply:

“My dear little one, I was born with the great advantage of not having anything inside my chest or head. What you call judgment and feeling are real mysteries to me. I don't understand them because I don't feel them.”

Soares added that fortune had supplanted nature by pouring a good sum of contos de réis into the cradle where he was born. But he forgot that fortune, although generous, is demanding and wants some effort from its godchildren. Fortune is not Danaid. When it sees that a vat has run out of water, it will take its pitchers elsewhere. Soares didn't think about this. He thought his possessions were reborn like the heads of the ancient hydra. He spent wildly, and the contos de réis, which had been so hard for his father to accumulate, slipped out of his hands like birds eager to enjoy the open air.

So he found himself poor when he least expected it. One morning, at the time of the Angelus, Soares' eyes saw the fateful words of the Babylonian feast written on them. It was a letter that the servant had given him saying that Soares' banker had left it at midnight. The servant spoke as his master lived: he called midnight at noon.

"I've already told you, "replied Soares, "that I only receive letters from my friends, or else..."

"From some girl, I know. That's why I haven't given him the letters the banker has been bringing for a month. Today, however, the man said it was essential that I give you this one."