Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

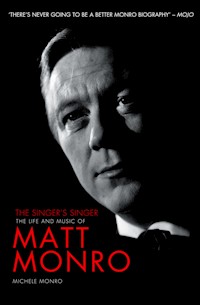

A singer once said "his pitch was right on the nose: his word enunciation letter perfect: his understanding of a song thorough. He will be missed very much, not only by myself, but by his fans all over the world". The singer was the legendary Frank Sinatra, The man he spoke about: the irreplaceable Matt Monro.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1210

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE SINGER’S SINGER

THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF

MATT MONRO

MICHELE MONRO

TITAN BOOKS

THE SINGER’S SINGER:

THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF

MATT MONRO

ISBN: 9781848569508

Published by

Titan Books

A division of

Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London

SE1 0UP

This edition September 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

The Singer’s Singer: The Life and Music of Matt Monro © 2011 Michele Monro

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive Titan offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at: [email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by the CPI Group.

OVERTURE

Author’s Foreword

A Portrait

A Childhood Interrupted

Privates on Parade

An Anagram of Moron

It’s Not How You Start

Decree Absolute

An Outing With Sellers

Prelude to a Storm

A Sting in the Tale

Brother Can You Spare a Dime?

La Di Da

Meet Matt Monro

It’s All Talk

Big Night Out

Hancock

Operation Santa Claus

A Bonding Session

Song Contests

A Matter of Association

The Big Dome

Showtime

A Raw Edge

A Couple of Fellas

Stomping at the Savoy

Black or White

The Judgement

Reviewing the Situation

The Power Game

Devil’s Harvest

The End of Capitol

Have Suitcase Will Travel

Suicide Watch

Once a Rat, Always a Rat

Hung Out to Dry

A Different Perspective

That Inch Makes All the Difference

Damage Control

Twelve Steps

Fifteen and Counting

The Sands of Time

Oysters to Go

False Tabs

Final Tabs

Cry Me a River

The Last Word

Acknowledgements

Michele & Max

This book is dedicated to my father

I wanted to honour his life and tell his story

It is not about my life with my father

It is not written from my point of view

But that of many family members, friends

and fans around the world.

This book is also for my son Max,

who never knew Matt Monro.

It is an integral part of life to know

your origins and family roots.

I hope this book brings insight into the man, the

singer, the husband, the father and makes Max

proud to know this then was his grandfather.

To my beautiful mother: who always enabled me to live

out my dreams even though hers were temporarily adrift.

They were joined in life and are now at last as one.

No goodbyes. Just passages of time. Until later.

xxx

AUTHOR’S FOREWORD:

SOFTLY... AS I LEAVE YOU

Cromwell Hospital:

Tossing and turning, then stillness, a vision begins to form, a room, stark, white, clean, clinical, almost virginal in its sterility. The odour of disinfectant is overpoweringly noxious with its undiluted presence. A clock, its only function to make the minutes pass too quickly, draining the body of life each time the second hand moves, an eternity. A stricken face lying on top of the sheets, like a dressmaker’s dummy, unstirring and as white as the linen itself. The inevitable drip attached to the mannequin’s arm, in perfect synchrony with the motion of the timepiece. Time itself has become the enemy, the judge and the ultimate hangman.

Genderless people move in and out between the life support systems as if on a crudely man-made obstacle course, each one careful not to intrude on the other’s duties, carefully playing with a myriad of dials and instruments on bleeping and blinking electronic meters. A game: if played in the right sequence, the ultimate prize – life itself – one false move, a splinter of error, then the booby prize.

Malignant cells spreading their vicious poison, a failed hepatic transplant because an extensive spread was not found until after the incisions were made – a bit bloody late to realise that, don’t you think? Thirty-two nameless people in a remedial tag-team who just lost the relay race against the devil. Someone’s vital organs now lying discarded and useless, thrown into a sterile tray marked for incineration.

A hand reaches out and touches, contact, warmth, feeling, sympathy, pulling me down an endless corridor of clinical detachment. Hundreds of people, faces merging together in an infinite maze. Everyone looking, peering, staring, their eyes boring into mine, searching for answers to unanswerable questions, heads tilting in mock sympathy.

Claustrophobia, a pressing heat, parched throat, cold clammy droplets of sweat dribbling from the creases of my brow, utter panic, legs moving, running faster than they can possibly go. Eyes blink, a mirage, doors, no, two doors, quite normal looking in their appearance but disguising the escape route I desperately crave, a trick of the light or a cruel optical illusion? Pressing, pushing, opening, falling and then the wonderful night air enveloping me with its coolness, the breeze embracing me with its fingers. The stars ablaze with compassion and understanding, their inner peace, calmness and serenity engulfing me with their tranquillity. A deep laboured breath, then another, each one urging my soul for the courage to face the clock. His scars will heal, but will mine?

Minutes, hours or days, no difference, still that same hospital room to be faced each time. I sit looking at the clock, wondering if yesterday has gone or is it already tomorrow. My eyes are heavy, weary with the hypnotism of the stillness. Holding the mannequin’s hand, sharing our sorrow with each other’s touch, without having to say the painful words. Sleep, an end to the nightmare of consciousness. My eyes open, just a fraction, just in case the set has changed. If things have altered I will close them again, maybe forever. Everything is exact, as before. I can wake to face reality. I glance down at the motionless figure, our fingers as entwined as a spider’s web. Our hearts no longer beating as one, mine: pulsating with youth, vitality and eternal love, his: slower with age, riddled with disease and lost vigour, but with no less love.

Movement, just out of the corner of my eye, rubber soles connecting with stone floors. It is lunchtime at the zoo. Hands reach to reconnect the new drip, tubes like spaghetti junction, sending the sterile saline solution, infused over thirty minutes, on its weary travels. Not too fast, not too slow, just at the precise speed. Do not pass go, do not collect £200, go directly to jail.

Tick tock, tick tock. I think they have turned the sound up on the clock; the monophonic pitch drowns out my thoughts. I must turn the volume down or think louder. I love you, I need you and love conquers all, doesn’t it? Even the evil spirits of the timepiece? Where there is life there is hope, what else do they say? Nothing, words are but empty letters formed together in vague meaningless sentences.

No single person can speak and cure the emptiness inside, the numbness that engulfs my limbs is all consuming. There is but a void, full of hot air, rage and bitterness. Is life that unfair that just when I am old and wise enough to understand the power of love and to have learnt what it is to be able to return it with complete unselfishness, it is taken away? The final gift vanishes before it has been given. The pupil is unable to show the teacher what she has been taught. Empty lessons... No, that is not what is required. The lessons must continue but from a different tutor. The lesson must be acknowledged from life itself. Hard or easy, the road must be travelled, wheels in motion towards the unknown. Not too fast, not too slow, just the precise speed, do not pass go... STOP, I’ve played that game before, rewind, the synapses are working in reverse, like a video in backward motion, the incessant celluloid holding vital caches of information. Memories of happier times, smiles, laughter, tears but this time with joy, running, talking, holding hands, unity, togetherness and love. I feel pain, heart pumping faster, breaths coming more quickly, tears welling up, panic. STOP. Buttons pushed, fast forward. The video stops at the required position, the present. I will concentrate on the present, on the future; I must not give up hope. We have been through worse, I think. Was there anything worse? Can’t think straight at the moment, the cameras have stopped, the video has broken... NO – only the pause button was pushed for a split second – relief.

There it is, the inevitable sound of the timepiece. Life is as it was, no more yesterdays, just tomorrows full of loneliness.

Play the game, please continue. My move, or is it yours? We will play later. I must sleep as you have done for a million years. When I wake up it will be your move, don’t forget.

Daybreak filters through my lashes, a glimpse of sunlight awakens my senses and I know it is a beautiful day. Another sound: music, harmony, a chorus line of skylarks on the windowsill running through their orchestration perfectly. Happiness has settled on the day. Fingers still entwined. Eyelids flutter, no, not mine, his, or just another illusion from the vestige of sleep. No, it’s there. His eyes focus on mine, my fingers squeeze his, his smile promotes mine. My tears, for my eyes only. No time for words, so much to say, but mustn’t tire him, they say he must rest. Rest, what else has he been doing for three days? Dying is their only reply, their excuse for not knowing the answers to my questions. The coma has passed, life has restored itself and the cocoon has burst, emitting a brilliance of colour, pouring out in never-ending rays of hope and achievement. The ultimate test has been passed. Full marks. The game nearly played out, just home base to reach and winner takes all. Well done, a brilliant manoeuvre. Letting your opponent think you were down and out, and just as defences were low, and reflexes off-guard, you pounced. The unexpected comeback, false tabs, a standing ovation to a full house, the orchestra plays on. Encore. Bravo. The house is full of old friends, your chair beckoning its master, aged and frail pictures smiling at me with calmness and tranquillity. Phone calls full of “I told you it would be alright”, full of cheer and warmth and then stilted, not knowing quite what else to say, so we’ll speak later. A promise of a good night’s sleep, pleasant dreams, home sweet home, a welcome call away from the nightmares of yesteryear. I will return tomorrow, after my dreams have ended and I awake.

Sunshine streaming into frosted panes of glass, shards of light fighting their way through the closed curtains, which have been drawn to shut out the paparazzi and their pugnacious obscene lenses. The kettle whistling for attention, no bills in the morning mail, only hundreds of get-well cards. Today so different from the rest, all the get-well wishers in the world who banded together have finally got their wish. The dream has come true. Getting better is the order of the day. Time to talk and listen to advice on how to travel the road to recovery. Clock ticking, faster and faster, but the fear is gone. It now races to heal the body of its ordeal. Chemotherapy now replaces the saline solution, its Mitozantrone drip giving the body the power to fight the disease and break down the filthy cancer cells that threatened to destroy our lives. It is another day suffering one more treatment, a further experimental test and so on, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera.

Vomiting racks the frail body but this is expected, swelling in the right leg countered with an intravenous drip and stitches removed from the ‘Mercedes Benz’ incision wound. Hopes are high that no further side effects take hold and the patient can return home until the next dose of Mitozantrone in a fortnight.

The warrior returns the victor, but in a blink of an eye the poison starts building again, the liver goes into failure, he can’t eat and a drip needs to be attached to pump the body with nutrients, the pain is too much, morphine is administered and an ambulance called.

I wake up, something is wrong, masks come into focus and blue gowns break down the harshness of the endless white. I am led and draped in the same costume as the other players, to protect him, they say. Protect him from what? Us is the answer, our germs, our nefarious contamination. The chemotherapy has broken down the life-destroying cells but they did not read the instructions on the packet. It could not differentiate the good from the bad and so has invaded them all. His white cells have faded and been destroyed by their own helper. The enemy has got the edge once again. Sleep again, pain, his, more drips. Chemo discarded like the joker in a pack of cards. Morphine to ease the burden of death. Can I have some please? I am dying inside, cell by cell.

That damn clock again, seeking its revenge, this time the victor, its hands drawing the final curtain across the stage of despair. The theatre emptying of its non-paying audience, the scene has been repeated once too often for them to sit there and watch the predetermined ending. At the first showing they reached for their hankies waiting for the tears that would fall, crying for the actors in the roles that they have been cast. Intermission. Time to stretch the legs, relieve themselves of the tensions of sitting on the edge of their seats for too long. A quick drink to quench the thirst of apprehension while the clock reaches the point where the second half beckons. The play resumes. The dialogue is being replayed like the video that re-runs the sketch. The cause of the deterioration is now bronchopneumonia and an intramuscular diamorphine cocktail is administered. This time no tissues, the crying was done in the first half. The audience ponder for just a fraction of a moment, as if to verify whether the author might have made a miscalculation. No, the scene is being played just as it has been written.

Fingers entwined, tears falling over the eyes that had hoped.

The clock finally comes to a standstill, its mechanism has at last worn out. The executioner has come to collect his prize. The waiting is over... or has it just begun?

Dreams or nightmares? Neither, just stark reality.

Goodnight daddy, I will miss you until the end of time itself.

Time of death 3.20pm: 7 February 1985.

A lone figure in a crowded arena, the face hung with misery and the burden of pain, a hundred tears falling silently onto the whiteness of the ground which has frozen into a crisp icy crust, just like my heart, which even the warmest of sunlight rays couldn’t thaw. It is so cold, the air freezing even as it leaves the mouth that utters empty words and promises of better days to come. I cannot remember a time of such steely weather that even the trees oscillate in disgust and the bleakness of the day conveys the thoughts of others. Tiny snowflakes drift down from the sky and I can only imagine that heaven must be crying too. I am alone in my grief even though there are a thousand faces looking on.

A blackness surrounds my being, am I asleep or dead? I feel in limbo where everything is blurry and disfigured and the world is running in slow motion. Bloody endless lines of people, pitying handshakes, mumbled condolences, silent tears and controlled hysteria. I want to go home and lock myself away from this wretched scene but... I don’t want to leave him alone here in a place full of strangers and nowhere to rest undisturbed.

The service is over. I don’t remember it beginning. Cameras flashing into the privacy of my soul and the long eternal walk down an aisle of no return. We are led to the best seats in the house, which is only fitting since we paid the highest price. All eyes watching... staring... at us, the mourners.

“The Lord is my shepherd”, is he? The lull of a monotonous tone waffling on about his life, what do they know about it? Turn to page thirtytwo in the hymnbook – or was it thirty-four? Who cares? All stand, all sit, bloody puppets on a string who are mechanically worked by a man uttering God’s commands.

All eyes focus on THAT box, lying solitarily on its pedestal, the expensive one because that is what he deserved – the best – it’s amazing that one inconsequential item can hold an entire audience captive. It just lies there and we wait until the final curtain closes and he has taken his final bow. Do we applaud his life or weep in his death?

I look around our home and all I see is him, his glasses by a crossword book, cigarettes in a green onyx box, a dressing gown hung so carefully by the shower waiting for its master to lay claim, his watch lying on his bedside table waiting for his return. This home that he built up for us to live in, is full of his being, his presence, but he is not really here at all. I feel so empty; no one will ever be able to explain any of this to me.

They say time heals, I say it is a burden. I’d give my life to turn the clocks back and start again but there are no fairy tale endings. Dreams are but lost causes and death is just an extension of life in another sphere, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

A PORTRAIT...

Matt Monro was one of the most distinctive singers to surface from the British pop scene in the early 1960s. In a career that spanned some of the most dramatic changes in popular music, Matt Monro stayed true to his musical style amid the growing popularity of heavy rock bands and guitar-smashing extroverts. That fact alone, coupled with his uniquely eloquent voice, earned him the admiration of his peers across the music business.

Along with The Beatles and the Bond phenomena, Monro was to become one of Britain’s biggest exports, with his characteristic laid-back style, cool sophistication and trademark middle of the road songs. Yet he had not been born into the glamorous world of show business nor with the name that would make him famous.

Terence Edward Parsons, the youngest of five children, made his first appearance in the world on 1 December 1930 to parents Alice Mary (née Reed) and Frederick William Parsons. Arthur was the eldest sibling, followed by Alice, Reg, Harry and then Terry, who was nicknamed Bo by his father.

Terry was born in an East End area of London known as Shoreditch, a geographical circumstance that made him a true Cockney. During the inter-war period, Shoreditch ranked alongside Hoxton and King’s Cross as one of the toughest areas in London. Thieving and violent crime were commonplace, shootings not infrequent, bloodstained clothing a boastful fashion and police always patrolled the area in pairs. Weekends saw vicious gang fights erupt in the streets. The most feared during that era was a bunch of Italians known as the Sabini Gang and during the 1950s and 60s there was another threat just three quarters of a mile east of the area – the infamous Kray brothers.

Terry Parsons aged 6

Terry’s father, Frederick, was a chemical worker and packer for a drug company near the Angel Islington. He’d had the same job since coming out of the army, where he fought in the trenches during the First World War. His wife, Alice, was petite, attractive and shyly self-assured; she was admired, consulted for advice and respected for her calm good sense by almost everyone who knew her.

Bringing up a large brood was expensive and Frederick worked long, arduous days. Alice, who cleaned during the day, set the tone at home. She was full of joy, loved having visitors and would go to great lengths to make them feel welcome. After dinner she would tackle the chores and stay up until everything was exactly as she wanted. She would then creep to bed in the early hours and grab a little sleep before going to work in the morning.

When Frederick became ill, his company offered to send him to Switzerland for treatment, but it was too late. He had suffered ill health after being gassed in the First World War and was incorrectly treated for malaria when he first became sick; it wasn’t until much later that a specialist hospital diagnosed tuberculosis. Doctors gave him a year to live; he lasted two, but his quality of life was exceptionally poor.

Alice spent long periods in the hospital tending to her husband while Terry grew up fending for himself. Gang culture existed in the streets, with most youths carrying knives in a bid to maintain their reputation. Gang members felt invincible and as they grew older they crossed the line from petty theft to the horrors of drug abuse. They knew no other way of life, had no guidance from their elders and craved respect and protection from those around them. The Parsons lived in fear of the children either being attacked or tempted into the culture themselves, but the streets were their natural playground and there were no alternatives. They could only pray for their offspring’s safety and their powers of resistance.

On 12 May 1934, after spending a year in hospital, Frederick died and although Terry hardly knew his father, he was devastated. He had vague images of visiting him in hospital and, on another occasion, of his father sitting on steps by a beach, but he was never sure whether these images were real or figments of his imagination.

Conditions in the underground mortuary where the body of Terry’s father was kept before burial were still antiquated. The gas-lit flag-stoned corpse chamber was connected to the hospital by a disintegrating brick passage. The smell was stomach-churning, but family members had to suffer the nasal assault if they wanted to pay their last respects. A local undertaker in Southwark Bridge Road took care of the burial arrangements, and Frederick William Parsons was finally laid to rest at Chingford Mount Cemetery in a pauper’s grave. He was only forty years old.

The Parsons family had already been living below the poverty line when Frederick was alive. As a widow with young children, Alice’s circumstances forced her to accept menial low-paid work, and as a result she had to find rent-free accommodation.

Alice brought up the children single-handedly, managing on her pension of ten shillings a week, which she supplemented with cleaning jobs. The family moved around the area, living without electricity in gas-fuelled accommodation, though they did once have the luxury of one bath in a house occupied by several families. Those rooms were desperate places, with bugs breeding under loose wallpaper and rodents a regular sight. After several months, the family moved to Welby House at Hornsey Rise. The barrack-like property was built as four low-rise blocks, providing lowrent basic living, gas lighting and outside ‘middens’ (toilets), which were cleaned out once a week by the council. The flat was sparsely furnished and washing facilities were little more than a bath with a hinged wooden top in the scullery, impossible to use with any privacy in the crowded flat. The best thing about the place from Alice’s perspective was that her children could play safely in the large open space between each block.

The kitchen was the hub of the home because it had a fire grate, which was black-leaded weekly with Zebo. The fire was the source for Alice’s stew cooking and the routine boiling of the kettle. Terry’s brother Reg was given the nightly ritual of banking the fire down, then raking over the embers in the morning to get it going again.

Reg and I used to huddle round the fire, which warmed us from the front but left a draught against our backs. I so wanted to warm my cold feet but resisted the temptation because of the painful itching that came from catching chilblains once before. — Matt Monro

Like all their friends, the Parsons had an outside lavatory. It would get hot in the summer, so Alice would hang herbs on the door together with squares of cut newspaper, and bitterly cold in winter, the seat so icy they had to work up the courage to sit down. At night it was a frightening place to visit. Reg remembers, “My brothers and I would hold out until we were desperate and then begged the others to come with us. We would wait for each other outside the door in the dark, scared stiff, urging the other to ‘get on with it’, with each strange noise bringing unbridled fear. Then we would run back to the safety of indoors, scuffing our skin in our panic not to be last in. I don’t remember what my sister used to do, as she never asked for our help.”

The children wore layers of clothing to keep warm, which were invariably ill-fitting as they were passed down from sibling to sibling. The bedroom was never heated and always felt cold and damp in the winter. It was a tortuous affair getting into bed until the chill had worn off. In fact, everywhere in the house was cold as a result of the high ceilings and stone floors.

Daily shopping was necessary as there was nowhere to store groceries. The small boys carried the weight of sugar, flour and potatoes home each day. Terry loved going to the grocer and, if he was lucky, it might be a day for broken biscuits, when his mother would buy half a pound, a luxury for the brothers. The boys drooled over the smells of freshly baked breads and in later years, when coming home from secondary school, Terry would walk the mile to purchase stale buns sold at half price from a local baker.

Terry Parsons aged 11 with his mother Alice

Losing a father at the tender age of three turned Terry into a rebellious child, and having no brothers or sisters of a playable age intensified his solitude. Though Alice was not an outwardly loving woman and had difficulty showing the boy the affection he craved, she was desperately trying to make ends meet and Terry’s attitude made it very difficult for her to cope. In later years Terry’s need for an audience was always there and he discovered that his talent provided the ticket to a form of social acceptance that he needed.

Terry’s early life was desperately unhappy and two years after losing his father, his mother, who was struggling to clothe, feed and house five children while also holding down a job, was taken seriously ill. There were no benefits or financial help from the State and, suffering from exhaustion and a mental breakdown, Alice was removed to a sanatorium. Her two youngest children, Harry and Terry, were placed in a foster home in Ashes Wood, Sussex, under the care of Mrs Driver, who took in children of parents who were unable to cope.

Terry hated it; he felt abandoned and didn’t understand that the placement was only temporary. He started biting his nails and became even more withdrawn.

After six months, Alice was released and, fearing that the Drivers were becoming too fond of her children, she immediately applied for their return. With their mother back at work, Alice and Reg were left in charge of Terry, who took to being very naughty, often escaping their watchful eyes and strolling in hours later without any attempt at an excuse or apology. His sister’s room was off limits but it didn’t stop him from ‘borrowing’ her lipstick and using it as a writing implement or from hiding Reg’s glasses. On one occasion, Terry’s ‘sitters’ took him to the police station, where Reg was friendly with one of the sergeants, and Terry was locked in a cell for a couple of hours to teach him the consequences of bad behaviour. However, the exercise proved ineffective.

Harry was no angel either, and was in the habit of standing on local balconies and taking aim at pedestrian’s heads with an arsenal of rotten eggs. Arthur, who was already out at work, also had his own idiosyncrasies. On Friday nights, after he had been paid, he would send Harry out to buy a new pair of socks, which he wore all week and then threw away.

Terry’s education was as unsettled as his home life, and he was shuffled between no less than four schools in a three-year period. He started at Bath Street School, but three weeks later was moved to Duncombe School. Then, less than seven weeks after starting his scholarly existence, he was admitted to hospital with infective hepatitis with a brace of birthdays celebrated in not the most congenial of surroundings, taking two years to recover.

It toughened me up. It made me count my blessings – when I had any to count. — Matt Monro

Terry then went to Parliament Hill Open School to convalesce. The Open Air School Movement marked a new period in preventative medicine. The schools took under-nourished slum students and children with serious illness and provided them with food and wholesome surroundings.

Terry wasn’t very interested in school and didn’t take to discipline very well. He was as sharp as a tack but lazy. Fantastic sense of humour and we laughed a lot; there wasn’t much that happened in life that wasn’t funny to us. The school doctor gave him his annual examination for symptoms of the prevalent TB and declared him fit to return to school. — Harry Parsons

Terry finally returned to Duncombe School but his distaste for the institution was blatant, as the school attendance register would indicate. His proudest boast during his schooldays was that by crafty manipulation and intense scrutiny of the attendance officer’s habits, he succeeded in attending class for only one solitary week in a whole year, and even that was only so he could grab second place in the school diving championships.

He also had to attend choir practice, but wasn’t allowed to sing as he was so out of tune he put the other children off.

Perhaps Terry could be forgiven for his lack of enthusiasm, as not every member of his family set the best of examples. Harry had won a scholarship to one of the better grammar schools but was expelled soon after for scrumping apples.

In 1938, Terry was moved to Hugh Middleton in Clerkenwell. The school had separate entrances for boys and girls and although it catered for both sexes there were no mixed classes, much to Terry’s chagrin. Though the dungeons under the school were out of bounds, Terry spent many a day with his friend Ben exploring the cellars that led to other corridors and passages, many of which had been blocked for years.

Eight months later, Terry was re-admitted to Bath Street. Existing records reveal no reason for this constant upheaval but with this sort of commitment to learning there was no danger of Terry becoming a serious student. It wasn’t his mother’s fault but circumstances that forced the situation. Despite Alice’s best efforts to provide a stable environment for the children, her situation forced yet another change when the family moved to Wenlock Street.

In those pre-pubescent days Terry had an inclination towards football. At seven he was scuffing his shoes in the streets running after the ball. His mother was always worried about the cost of new shoes, but lengthy lectures did nothing to curtail Terry’s enthusiasm for the game. By age eight he was a solid little player. His street friends recognised his potential, and his speed and ability with the ball earned him a place on the local team.

A big match was arranged on a neighbourhood field and as word of the event grew, so did the number of spectators. Not long into the game Terry missed an important goal, much to the disapproval of the partisan crowd, who started booing from the sidelines. With the score still nil–nil after half-time, the crowd grew boisterous again when the opposing team gave a penalty. But Terry refused to take it, fearing scorn from his newfound friends if he repeated his mistake of earlier. His team elected another player, who lined up for the shot and promptly missed as well. The crowd became abusive with a divide forming between the supporters of the two teams, resulting in the police being called. The match resumed and moments before the final whistle, Terry had a clear run opportunity of sprinting the ball up the field, and without a moment’s hesitation he kicked the ball into the back of the net. The whistle blew, the crowd went mad, he was hoisted onto the shoulders of his team and for the first time in his life Terry felt a confidence in himself that had never been there before. He felt like a giant.

Though it was to be Terry’s last football match, those memories stayed with him for the rest of his life.

The only thing that featured in Terry’s life more than football was music. Turning on the kitchen’s battery-powered Bakelite wireless produced an orange glow behind its large display, and as the valves warmed, a low drone would follow and slowly a muffled sound emerged from the gold, meshed material covering the jaws of the speaker. Permanently tuned to Radio Luxembourg, it proudly showcased popular and big band music like Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey and Ella Fitzgerald. This was Terry’s first introduction to the musicianship of Bing Crosby, Fred Astaire, Perry Como and Frank Sinatra, but it wasn’t just the Americans that were impressing. In the United Kingdom, bandleaders Joe Loss, Harry Roy, Ambrose, Roy Fox and Ray Noble all had orchestras which featured the most famous band singer of the time, Al Bowlly.

These were good times, but the small machine that housed the magic of music would also bring devastating news a year later.

A CHILDHOOD INTERRUPTED

By the summer of 1939 war was imminent. School halls issued gas masks and the stench of rubber, when the masks were forced over children’s faces, resulted in coughing, choking and in some cases vomiting. A square cardboard box, housing the offending item, was given out with a compulsory order to carry it at all times. The school then announced that the children would be evacuated as a unit, and drills were practised so that assembly points were known. Children were required to hang a card around their neck listing their seat number on the bus. Practice was relentless, but they had no idea when they would be forced to leave their families.

Along with their identity label and gas mask hanging from their neck, each child also had a small bag for clothing and food for the day. They left in the early hours of the morning under the umbrella of darkness. As parents and guardians were not allowed to go with the children, the police were brought in to enforce the policy.

The first school children were evacuated on 1 September 1939 – the day that Germany invaded Poland – in a manoeuvre named Operation Pied Piper. In the first three days of September nearly three million people, mostly children from inner cities, thought to be the most vulnerable to Nazi bombing raids, were transported to the countryside. The railway platforms were crammed with the uproar of shouting officials and sobbing children who had no idea of their destination. As they departed, the children thought they would be home for Christmas.

More disorientation followed, as after their arrival, the children were lined up against a wall and local residents, acting as foster parents, were invited to take their pick. This was just one of the moments of humiliation for the evacuees. The government campaigned with posters and advertisements to convince parents to send their children to a better place, on the mistaken assumption that there was enough accommodation to house everyone. For many it was an experience which gave them a better life, but others were not as fortunate, suffering beatings, mistreatment and abuse at the hands of ‘carers’ who were only looking for cheap labour. Under the conditions of indiscriminate evacuation, Terry was one of thousands of artificial orphans created by the war, and his memories of the trauma of separation were so painful that he rarely talked about it later in life.

Terry was evacuated to Cornwall but immediately made the decision that he wasn’t staying. After enduring quite enough of his enforced exile he made his own way home, arriving on the doorstep and declaring he wasn’t going back.

A child’s perspective of life in wartime London was very different from their parents; for them, it was an incredible adventure. Shrapnel from the bombing raids was collected as keepsakes on the way to school. One evening an incendiary bomb fell and hit the cover of the manhole outside Terry’s home. Although it damaged the cover, it didn’t detonate and the appearance of men in special overalls who came to remove it caused great excitement among the neighbourhood boys.

During the Blitz, huge areas of London’s East End were reduced to rubble, the brunt of the attack being focussed on the East End Docks. The area was in chaos as smoke and flames engulfed the Parsons’ neighbourhood. Terry’s family were bombed out on more than one occasion and they routinely had to pack up and move. They were also forced to spend several nights in the communal shelter. It was noisy and the air was hot and stank, so when the ‘all clear’ siren sounded they were thankful to climb back into their own beds.

At a new school – and there were many during the early years of the war – bullying was commonplace, although Terry could hold his own. Swimming and boxing had strengthened him and, after defending his corner on a couple of occasions, he was left alone while they targeted a weaker child. Schools were over-crowded, as many of them had been requisitioned as makeshift morgues, and working class life was hard and brutally competitive – individualism was what kept your head above water.

The constant bombing, petrol and food shortages and the blackout meant that most people spent a lot of time in their homes. Terry’s mother still went to work, making just enough money to feed the gas meter and buy some coal. She had already sold the few possessions they had to make ends meet. To combat the terror of the raids and claustrophobia of the home, people also took refuge at the cinema, where for one or two pennies they could escape reality for a few hours. More often than not the kids couldn’t afford the ticket price and would ‘bunk in’, picking the lock on the fire safety doors with a bent piece of wire.

I remember during the war going to Crouch End Broadway. We used to bunk in every Sunday. I remember sitting through two or three performances just to see a film and walking home during the air raids with all the shrapnel falling around. — Matt Monro

Harry had also returned home briefly, but he and Terry were soon evacuated again, this time together, to South Luffenham. Arriving in the countryside after living in a big city was alarming. Although there were woods, fields and open spaces, the village itself felt small and unfamiliar to the two boys. Instead of the characteristic red beacons of London, the countryside buses were grey and only ran once a day. It was another huge upheaval for young Terry. However, the brothers only stayed a few weeks since the village didn’t have the facilities to educate Harry.

After South Luffenham, Harry was next shipped to Linslade, Leighton Buzzard, this time to the Pantlings’ residence at 90 Soulbury Road. Terry was put on a train from London and turned up at the three-bedroom council house asking for Harry, and the family put him up for two nights. Alice asked Hilda Pantling if she could help find lodgings for Terry so that he could be near his brother, and she turned to her close friends Bob and Liz Watson, who lived with their children Grace and Joan on the same road at number 76. On Terry’s arrival there was a freshly-made cake and lemonade waiting in the kitchen and a small, neatly made up bedroom at the top of the house. Terry had never had a room of his own before, or a cupboard or even a drawer. This was a luxury not even afforded to adults in his family.

Terry went to The Boys School in Leopold Road under the watchful eye of headmaster Mr Samuel, while Grace Watson attended The Girls School. They did the regulatory arithmetic, spelling, writing and reading. Both schools were very strict – naughty children were kept in at the end of the day and in extreme cases the cane would come out of hiding. Although Terry was not a lover of church he sang in the boys’ choir with three other evacuees at St Barnabas’ Church. When Christmas came Terry joined others to tour the village singing carols.

Sunday was considered a day of rest, so the children were not allowed to play, but as a rare treat they would go for walks along the canal. The river was the best place to fish and the boys often competed against each other for the most impressive catch. When the weather dictated, although lacking in trunks, they would swim in the icy waters to cool down. If they heard anyone coming they would hold their breath under the water until the strollers had passed so as not to get in trouble.

At the back of the house was an expanse of fields, including Bluebell Woods, and Grace and Terry used to go there to climb trees, go apple scrumping and fool around under the hayricks. Terry started smoking at eleven and persuaded Grace, who was older than him by a few years, to try it out, then bribed her to buy him packets of Woodbines – threatening to spill the beans to her parents if she refused.

At fourteen years of age, Grace started work for Aquascutum as a machinist making uniforms for the troops and receiving fifteen shillings a week. Terry found work in the cellars of the local pub, The Clarendon, by lying about his age. The two children spent nearly all their time together. Terry was the younger brother Grace never had and Terry shared her affection.

The village was fairly quiet and there was very little to remind the children that a war was going on apart from occasional army manoeuvres through the small street. If they wanted information on the outside world they would visit the cinema to watch the Pathé News.

Terry stayed at Linslade Junior School and he and Harry would occasionally go to the cinema together in Leighton Buzzard. Their mother had a friend who worked on the railways and sometimes got privilege tickets, which was how she managed to visit the boys every few months. On one visit she took Harry home with her. He was four years older than Terry and it was time for him join the workforce as a plumber’s mate.

Terry didn’t pass the eleven plus exam. Those that failed were moved into another building and remained there another two years, until they were released from school at the age of fourteen to become shop assistants, errand boys, apprentice tradesmen or Watney’s Brewery girls. Terry left Linslade before he was fourteen after a stay of two years.

Terry arrived home to find streets of abandoned houses. Many of their neighbours had not fared well and had left their homes for safety elsewhere. Terry had seen a lot of collapsing buildings since the war started, but it was nothing like seeing this, right by his own home. He took to the streets with his old friends and little gangs formed, who set up base and played imaginary war. The boys climbed through shattered windows and found a disused wonderland of enormous houses and empty flats. Other small gangs had the same idea, and it was often a race to see who could claim the spoils of war first. The friends scrambled through the rubble, collecting items left behind by previous owners, amassing what they could in the hope of a quick sale to earn a few pennies. They were very inventive when it came to ways of making money.

We used to go ‘coking’ at the weekend, down to the gasworks. We’d collect sacks of coke and earn a farthing for every sack. People needed it to eke out their coal, which was in short supply. If you had an old pram or a pushchair you could fetch more than one sack at a time. — Matt Monro

South Luffenham School

Alice was not happy about Terry being home. She felt it was only a matter of time before he would get into trouble in London, so in 1943 she made arrangements for him to be billeted out of the city with a middle-aged couple, Charles and Rosetta Hudson, who already had a young lad living with them in South Luffenham. Alan Fox had been in an orphanage before being fostered by the Hudsons and with Terry’s arrival he had company for the best part of a year.

South Luffenham was a small village in the county of Rutland, with only two shops, a combined Post Office and general store, and a provisions store and greengrocer. Rose and Charlie lived at number three in the middle of a row of five cottages called Flower Terrace. They were an elderly couple who had never had children of their own and felt that by taking in evacuees they were helping the war effort. They were strict but caring and gentle people and Terry grew very fond of them. The cottage had a long, large garden complete with outhouses and a pigsty. There was no electricity or telephone, only paraffin oil lamps and candles. Cooking was done on a hob on one side of the fire grate with a water tank on the other, both heated by an open fire burning wood or coal. There was no fridge but they had a sizeable larder that kept the food cool. The cottage had three bedrooms, the main one for the Hudsons and two double beds in the other two. Alan shared with another evacuee, Ray Harper, and Terry shared with Ray’s brother, Malcolm.

The Post Office shop took me on to deliver papers and I collected two shillings and sixpence in tips, which I used towards buying myself my first long pair of trousers.

— Matt Monro

The rector of the parish church was Reverend Brown, but the boys called him Biff. He was extremely fond of his ‘vacs’, as he called the children, and used his car to take them on regular swimming outings to Peterborough and visits to Wickstead Park in Kettering. He also allowed the boys the use of his bicycle, teaching most of them how to ride. All the children were obliged to attend church every Sunday and Aunt Rose encouraged her charges to join the choir. She had a lovely singing voice herself and had been a member of the Uppingham Choral Society in her younger years. One of her choirmasters was Malcolm Sergeant, who went on to become a renowned conductor. Alan and Terry were both members of the church choir, and the Reverend took full advantage of their abilities, repeatedly selecting them for solo parts, which they secretly enjoyed.

The village school housed two large classrooms, one for infants, the other for the over sevens. Mrs Tebbutt, the headmistress, would arrive from nearby Stamford, where she lived, and the girls would go over the fields to meet her. The boys would accompany them, mainly to enjoy the freedom of the open air and run alongside the riverbanks that cut through the fields. The school cook was Mrs Russingham and all the evacuees stopped at school for dinner. On a child’s birthday she would make their favourite pudding, which was guaranteed to earn her a smile.

When they weren’t in school or singing in the choir, the boys had plenty of chores to keep them busy. They trekked up to the woods to collect logs and small branches to make kindling to light the fires. They fetched the milk from Farmer Bellamy and helped plant vegetables in Uncle Charlie’s two allotments. Charlie was head herdsman on Pridmore Farm and the children would help out by taking the cattle to Stamford market, a walk of nearly eight miles. There were no standpipes in the area, so all the water had to be fetched from the spring that flowed into a well in the middle of the village. Terry filled six buckets with drinking water each day and kept a large outside tank topped up for washing and cleaning.

Breeding rabbits was one of Uncle Charlie’s sources of income and every day Terry and I had to fill four sacks of rabbit-grub containing dandelions, cow parsley, sour thistles and cloves from the fields and hedgerows.

— Alan Fox

Aunt Rose was an excellent cook, making up meals of vegetables, homemade bread, butter, jam and cakes. She even made her own wine in flavours ranging from rhubarb, elderberry, ginger, parsnip and carrot. They would have meat twice a year when Uncle Charlie selected one of the pigs for slaughter. Local butcher Bitty Lake would come and kill the animal in the garden, cutting it into hams and flitches and providing bacon, sausages and pork pie, though the lion’s share always went to the grown-ups. The cuts would be put on flat trays, preserved in salt and put in the long pantry. When the pigs were being fattened all the people in the village who didn’t keep animals would bring their scraps around to help with the feed. They knew that Pig’s Fry – a mixture of kidney, liver, and pork belly with bacon on the top – would be doled out to them later, taken home on a plate covered with a napkin. It was a good time for the whole neighbourhood and everyone got a decent meal.

The children under Rose and Charlie’s care formed a close-knit group and often used nicknames for each other. Alan’s was Tester, as he was always chosen to go and try things first. Terry earned his moniker, Bramble, on one of his many trips to Spano Aerodrome. The runways were close to the perimeter fence and were in disrepair, with huge cracks spreading across the tarmac. Within the cracks, blackberry brambles grew in circles very low to the ground. There were loads of blackberries and very large ones too, so the boys often stripped off their shirts and set about collecting the fruit. A good haul might make them some pocket money. Terry was a good deal shorter than the other boys and instead of leaning over the brambles to pick them he noticed a small gap in the bush and crawled through to grab some extra juicy ones. When the boys had enough and were getting ready to go home, Terry found he couldn’t find the gap he had crawled though and became trapped in the middle of the bramble bushes. The boys all wore short trousers so couldn’t get in to help their mate without getting ripped to shreds by the thorns. They called on the help of some beet workers in the surrounding fields who came and cut him out, laying coats over the brambles to prevent being caught in the thorns. Laughing at Terry’s predicament, they assured him they would soon have him out, calling out, “come on Bramble, let’s be having you”. The nickname stayed with Terry throughout his teenage years and ended up gaining Alan access to Terry twenty years later.

Once again, it was time for Terry to return home to London. The city had been left badly damaged and the buildings that remained standing looked shabby and in desperate need of repair. In that spring of 1945, Terry had a strong sense that his childhood was over.

I remember Mum’s face, full of tears, full of joy at having me home again. This woman who had lived through two world wars, still stood upright with open arms. — Matt Monro

Terry came back to a very different family scene. Harry had entered the Royal Air Force as soon as he had turned eighteen, ending up as Acting Sergeant Instructor at Lyme Regis, as had Reg. Harry and Terry would often visit Reg at Mill Hill Barracks where he was based and they were always guaranteed a few free drinks. Arthur, the oldest, was married and both he and Alice were working.

Terry’s war heroes were the RAF boys Alice brought home. It used to cost her a packet of chewing gum or a chocolate bar to get rid of him so she could steal a kiss and a cuddle.

Fourteen was the earliest age you could leave school and Terry was forced to so he could go to work. He found himself undertaking a succession of mundane jobs; his first was with the Imperial Tobacco Co, where he started in the factory as an offal boy collecting waste tobacco and sweeping up the debris from the cutting machines. Terry recalled that the post-war tobacco shortage was greatly increased by his own personal consumption at source. Terry kept five shillings of each week’s salary before handing the rest over to his mother, but she wasn’t left with much as she insisted on paying her son’s fares and dinner money.

Terry was always enthusiastic about starting a job but boredom quickly set in. He drove a lorry delivering Guinness for the Bulldog Brewers, but that only lasted a week. A series of jobs followed, including office worker, apprentice to a master builder, fireman on the old London North Eastern Railway Line from King’s Cross, as well as a plumber’s mate, decorator’s mate and a plasterer’s mate. Terry kept searching for the one elusive job that could hold his interest. Next came attempts as an electrician, coalman, bricklayer, truck driver, kerbstone fitter, factory floor sweeper, stonemason, milkman, baker and even a general factotum in a custard factory. Terry even claimed to have put the heating system into Vauxhall’s at Luton. Jobs came and went. In one year he held a total of fifty-three jobs. He detested all of them.

The music scene saw many changes nearing the late 1940s. Discs were played on 78rpm records, pressed on shellac (a brittle material that was easily scratched) and played on wind-up gramophones that pushed the sound through steel needles. Recording methods had their limitations and lack of space on the disc meant that no piece of music could exceed three minutes. The elite could afford all-electric gramophones with loudspeaker amplification. In America, the jukebox became all the rage, launching a clutch of young stars by repeated playing of a song along with continual requests on wartime radio shows, which helped sell the idea of the hit record. American radio show Hit Parade began playing the top selling music of the week and Billboard magazine also published its first Music Popularity Chart. ‘I’ll Never Smile Again’ by Tommy Dorsey, with vocalist Frank Sinatra, was the first ever ‘Number One’ record, an achievement honoured by the presentation of a gold disc. Thereafter it became every artist’s aim.

Terry’s love of music hadn’t waned and his childhood years were spent listening to the magic that emanated from the radio. At first he was unimpressed by Sinatra, but in later years firmly believed him to be the best interpreter of a song. He also loved Perry Como and remained a great admirer of the man throughout his life.

I used to listen to Peter Potter on Voice of America through the American Forces Network. Perry Como was the singer and hearing ‘Prisoner of Love’ set my sights on a musical career. I’ve never seriously learned to play a musical instrument but I wish I had.

— Matt Monro, Hong Kong Sunday Post-Herald

From the age of fourteen Terry spent as much time as he could either practising his singing or performing for other people. The first time he sang with a group was in his teens at the Tufnell Park Palais in North London with The Bill Evans Band. He was trying to impress a girl he was dancing with, hoping to escort her home, and began singing in her ear. She told him that if he really had to sing he should get up on the stage. Being dared by friends and with his confidence boosted by a few beers, the young boy took his youthful courage into his hands and did just that. He asked Evans, who played saxophone, if it was all right to sing a number. Like all good fairy tales, Evans was so impressed with the impromptu performance that he gave Terry a regular Saturday night spot with the band, singing two songs for ten bob a night. One of the numbers, ‘I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now’, was Terry’s star turn.

I always used to hang around the ballrooms like the other guys when I was about fifteen years old. As with other local kids, I used to go into the pub to have a few pints, then the lads used to say, “Why don’t you get up and sing a song?” and I did and people seemed to like it. That was more or less the start of it. Every kid seeks admiration and that was my ego trip. — Matt Monro

Another one of Terry’s favourite singing haunts was The Brecknock Arms, conveniently located near to where he lived at Kingsley House on the Brecknock Road Estate. Harry recalled also going with Terry to a pub in York Way. People often referred to him as Perry Como, because Terry had modelled himself on him. “It was only later that he developed his own style. Bowie, as he was known to family and friends ever since our father nicknamed him, never owned any records because he was always broke but listened to the radio all the time. It was only when I heard him sing at The Boston that I realised how good he was, then at Hornsey Town Hall. He was very popular with the girls. One rang the house and after the required small talk she asked Terry to sing to her down the phone, but Terry kept saying no. He told her if she sang to him first, then he would sing to her. My brother-in-law, a telephone engineer, hooked up the telephone to the valve speaker on the radiogram and this girl sung and made the most frightful noise you’ve ever heard in your life – we all had a laugh. After that he was obliged to sing her a few notes.”

Nobody else in the family could sing. In my case God saw that I couldn’t do anything and had nothing else going for me. So he decided: “I’ve got to do something to help this poor bastard.” — Matt Monro