3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hesperus Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

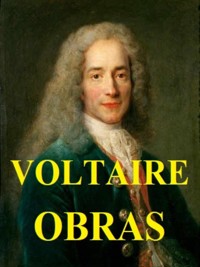

Written in the tongue-in-cheek manner for which he was famous, Monsieur de Voltaire's memoirs reveal a new perspective on the international politics and history of the 18th century. Voltaire's role as acclaimed author, poet, dramatist, and philosopher led him to experience the personal attentions of the most illustrious men and women of his time. His irreverent, to say the least, portrayals of the leading figures of the day provide a hilarious portrait of the royal courts of Europe which fought over his services for almost 30 years. Only published posthumously, these memoirs relate and then commentate on literary accomplishments, historic fact, and salacious gossip alike.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 161

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF MONSIEUR DE VOLTAIRE WRITTEN BY HIMSELF

VOLTAIRE

Translated byANDREW BROWN

Foreword byRUTH SCURR

Hesperus Classics

Published by Hesperus Press Limited

First published in 1784

First published by Hesperus Press Limited, 2007

Introduction and English language translation © Andrew Brown, 2007

Foreword © Ruth Scurr, 2007

Designed and typeset by Fraser Muggeridge studio

Printed in Jordan by Jordan National Press

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-84391-152-4

ISBN (e-Book): 978-1-84391-975-9

This e-book edition published in 2023.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

Memoirs of the Life of Monsieur de Voltaire Written by Himself

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

FOREWORD

None of us knows which, in retrospect, are the best years of our lives. The time of deepest happiness, greatest achievement, or most passionate love may not always announce itself in passing. And even when one suspects the best has been and gone, it is hard to stop hoping better will come.

In Voltaire’s life, 1759 was pivotal: the year he published Candide (or Optimism) and spread throughout Europe a humane challenge to the enormity of human suffering: ‘Appalled, stupefied, distraught, covered in blood and shaking uncontrollably, Candide said to himself: “If this is the best of all possible worlds, what must the others be like?”*

Candide was an instant best-seller, adding to Voltaire’s already considerable wealth. Aged sixty-five, worth about a million livres, he was living outside Geneva on estates he had purchased at Ferney and Tourney. In his Memoirs, composed around this time, he boasts, ‘I have so arranged my destiny that I am now independent both in Switzerland, on the territory of Geneva, and in France. I hear a lot of talk about freedom, but I do not think there has ever been an individual in Europe who has procured himself such freedom as mine.’

Free as he felt himself, Voltaire looked back with bitterness on the constraints he had had to overcome. The ‘shitbags of literature’ for a start: those who had libelled and defamed him because they were envious when his plays and poems succeeded. Since childhood, he was set on a literary career, but categorically dismissed the delusion that it might prove a means to freedom as well as an expression of it. ‘I have always preferred liberty above everything else. Few writers can say the same. Most of them are poor; poverty wears down one’s courage; and every philosopher at Court becomes as much of a slave as the first officer of the Crown.’

Despite himself, he found power seductive. ‘Everyone knows that you have to suffer indignities from kings’, he wrote, but his intimate relationship with royalty was consensual. Frederick of Prussia sent flattering letters to Voltaire, who obtained permission from Louis XV of France for an extended visit to Berlin. Poetry and philosophy were common ground between Frederick and Voltaire. They fell out when someone spread the rumour that the latter thought the former’s poetry no good. The rumour was true and in his memoirs Voltaire makes relentless fun of Frederick’s feeble versification. Afterwards, in retreat near Geneva, he was delighted to discover ‘what kings never give, or rather what they deprive one of: peace and liberty’. And yet, he cannot resist mentioning that since he acquired tranquillity, far from court, Frederick has begun communicating again, sending yet more poetry, an opera that is ‘the worst thing he has done’.

Love was another constraint. Voltaire’s brilliant companion, the scientist and scholar Emilie du Châtelet, died in childbirth in her early forties. The child was neither her husband’s nor Voltaire’s. All concerned were grief stricken. While she was still alive, Voltaire claims, he told Frederick that ‘philosopher for philosopher, I prefer a lady to a king’, but after her death there was nothing to keep him from Prussia. Following the deterioration in his relations with Frederick, Voltaire found ‘the consolation of my life’ in his niece, Mme Denis. She was with him as he contentedly composed his memoirs: ‘While I was in my retreat enjoying the sweetest life imaginable, I had the small philosophical pleasure of seeing that the kings of Europe were not able to enjoy this same happy tranquillity, and of concluding that the situation of a private individual is often preferable to that of the greatest monarchs.’

Voltaire professed himself so happy he was almost ashamed, gazing out from a private idyll at war-torn Europe, ruined and drenched in blood. In May 1759, he received yet another unwelcome poem from Frederick, insulting the king of France. Dragged against his will back into politics, he informed the French authorities, who arranged for a counter poem to be composed, insulting the King of Prussia. Voltaire played amusedly with the idea of these two absurd poems becoming the foundations of European peace. Then invoked Corneille: ‘This, my lovely Emilie, is the point we have reached.’

The quote is poignant with Voltaire’s own Emilie ten years dead. It was, he noted, somewhat ridiculous ‘to talk about myself to myself’:he was starting to feel lonely. The memoirs are sanguine – sometimes joyous – in tone, but they carry an undercurrent of something far worse than reckoning past mistakes or insults, even when the bitterness they caused still lingers. It is the simple passage of time. There was much still ahead of Voltaire. He died in 1778, having composed (or perhaps dictated) in his last few years another autobiographical fragment (Commentaire historique sur les œuvres de l’auteur de la Henriade). By the end of his life his grief for Emilie and his disappointment in Frederick had tempered, even if his irritation at the ‘rascality of literature’ never diminished. By contrast, the earlier memoirs are raw. In 1759 Voltaire was still close to the defining events of his public and private life. He had found refuge in Mme Denis and their estates outside Geneva. He was about to throw himself into improving the lives of his villagers and publicly campaigning against infamy. There is no reason to think he protested too much when he proclaimed the almost embarrassing extent of his private happiness. And yet there are hints in the memoirs that he already knew the high tide of his passion had passed. He would never again fall prey to ‘utter-devastation’ at the death of a woman he loved, or fail to resist the flattery of ‘a king who was also a poet, musician and philosopher, and who claimed to love me’. The memoirs of 1759 are precious above all for showing us how Voltaire saw his life when he was at its imaginative centre: on the cusp between living expectantly and recollecting in tranquillity.

– Ruth Scurr, 2007

* Candide, or Optimism, translated and edited by Theo Cuffe (London: Penguin, 2005).

INTRODUCTION

‘A scandalous libel’, Carlyle called it. The dyspeptic Sage of Chelsea had no great admiration for Voltaire’s Memoirs, since the person they (in his view) libelled, Frederick the Great, was not only a personal hero of his, but the man over whose biography he laboured (plagued by more than occasional doubts as to whether the Prussian King was entirely worth such devotion) between 1851 and 1865. Instead of taking Voltaire’s comparatively brief and improvised work as a contribution to our understanding of Voltaire, Carlyle read it as essentially being about Frederick. And as such, it was a complete travesty of the facts, written by Voltaire in ‘a kind of fury’ as an act of revenge on a king who had first courted and then humiliated him; a work filled with ‘wild exaggerations and perversions, or even downright lies’, one which imputed to Frederick ‘all crimes... natural and unnatural’, and was, in its frenzy, like a ‘Devil’s Head, done in phosphorus on the walls of the black-hole’ by an artist locked up, with justice, as a madman.

While the Memoirs do not quite live up (or down) to the blistering anti-hype of this splenetic bluster, they are certainly one of Voltaire’s most fascinating, and yet lesser-known, works. That we can read them at all is fortuitous. Voltaire seems to have composed them in conditions of relative secrecy: he may have intended them for only posthumous publication. Their asperity of tone, mocking disrespect for the Establishment (or those of its members who had happened to offend Voltaire), indiscreet gossip about eminent personages, and saeva indignatio at the persistence of l’infâme, might well have made publication too dangerous while their author was still alive and (despite his fame and his prudent residence just the other side of the French border) still subject to the caprice of monarchs and the rage of prelates. Some scholars say that he burnt the original of the Memoirs, but made at least one copy (which was then, to his chagrin, stolen). But this was a man who seems to have wanted everything he ever wrote (and a great deal of what he said) to be, sooner or later, in the public domain. At all events, his niece, Mme Denis, inherited his papers on his death, and two copies of the Memoirs were found among them. One ended up in St Petersburg, as part of the library of Catherine the Great (who at one stage showed an interest in having Voltaire’s entire oeuvre published in her capital city); the other was purchased by Beaumarchais, who had rented an old fort at Kehl, on the Rhine, and set about publishing (on twenty-four printing presses) the first Complete Works, in which the Memoirs were the last volume.

The Memoirs had probably been written in 1758–9, making them contemporary with Candide. In their almost ferocious gaiety, with sporadic moments of anger and an underlying ostinato of resentment, they have an off-the-cuff feel about them – but that is true of so much of Voltaire. They end in a series of addenda, written in Voltaire’s Swiss retreat at Les Délices, bringing the story up to date while also suggesting an implicit ‘to be continued’. Are they really more about Frederick than Voltaire? Some (like Carlyle) have indeed treated them as a disguised mini-biography of the Prussian King, a view partly shared by Goethe (he thought that Voltaire’s gossip on Frederick’s sexual tastes was similar to Suetonius on the Roman emperors). Much of Voltaire’s life during the period he discusses is omitted from them: there is (no doubt with good reason) little here on some of the most salient episodes of his time in Berlin (his shady financial wheelings and dealings, or his subsequent distressing legal hounding of the businessman Hirschel, whom he seems to have attempted to swindle). Admittedly, they are no more elliptical and selective than most autobiographies. But they are best seen as the memoirs of a relationship – even their last pages return, obsessively, to the ‘perfidy’ of the King of Prussia, and wonder with grudging admiration what the old fox, whose French poems (some of them daringly anti-Christian, many of them licked into shape by Voltaire himself) had just been published in Paris, would get up to next. Frederick’s alert, querulous, domineering, mocking presence haunts these pages almost as much as does Voltaire himself (to whom the same adjectives apply). We do learn about other people who counted in Voltaire’s life, but much more tangentially. Madame du Châtelet, for instance, the love of his life, his intellectual partner and fellow student in the latest and most fashionable English science (Newton), is praised for her brilliance (while gently teased for taking Leibniz and other metaphysical systems too seriously: the ‘spinning of spiders’ webs’, Voltaire called it in a letter to Maupertuis). Voltaire’s grief at her early death (we know from other sources that, when he staggered out of the room in which she had just died, he was so distraught that he fell down the stairs and cracked his head) is evoked in terms all the more powerful for being laconic. But Voltaire is silent on the stormy ups and downs of their relationship, just as his long affair with his niece, Mme Denis, is barely mentioned. Indeed, in the Memoirs, both these women are forced into positions of relative subservience to Frederick, forced to orbit as satellites round the ambiguous gleam of the sun of Potsdam. Madame du Châtelet’s role here is essentially to show jealousy when her lover is taken away from her by the King of Prussia; Mme Denis’s role is to give her uncle a pretext for expressing even more rage and resentment at their arrest in Frankfurt, on Frederick’s orders. Cherchez la femme is not good advice for reading the Memoirs: there is a love story here, but it is that between Voltaire and Frederick. And like most love stories, it has its initial flirtations, its out-of-the-Prussian-blue coup de foudre, its honeymoon, its moments of tranquil contentment overshadowed by the first lovers’ tiffs, its increasing tensions, rows and makings up, its petty jealousies and deepening possessiveness, its decline into distance and distaste, its apparent explosive final falling out, and then, once they are safely separated by several hundred leagues, a tentative rapprochement, a mutual curiosity (‘what’s the old rascal up to now?’ they both think), and overtures for peace (‘but surely we can still be friends?’). But nothing would heal the trauma left by the infamous scenes of arrest, bureaucratic bullying and real terror inflicted at Frankfurt by the henchmen of the King of Prussia, showing at last who was the real master – though Voltaire’s behaviour, issuing satirical skits like so many Parthian shots against his erstwhile employer, as he fled back to the unwelcoming embrace of a France from which he was still officially banished, was wonderfully provocative (French and German historians still argue over who comes out of the affair looking worst). From then on, the relationship between them was conducted by letter alone, or mediated by the vast network of gossip that constituted the international Republic of Letters: they never again met.

And it had all started so well! The Francophile Frederick was, even before his accession, cultivating some of the leading French intellectuals of the day with the eventual aim of adorning and enlightening the court of an increasingly self-confident and powerful Prussia; soon he was flirting by letter with Voltaire, whereupon there ensued an exchange of rococo compliments (Voltaire calling Frederick a new Solomon) followed by their first meeting, in Frederick’s tumbledown residence in Cleves, on 11th September 1740. As with most accounts of love at first sight, Voltaire’s report of this is apparently unreliable (he was, after all, writing nearly twenty years after the event), but oddly poignant: Frederick, in his late twenties, laid low by quartan fever, sweating and shivering in bed, dressed in a shabby blue dressing gown; Voltaire, nearly a score of years older, going over to him and, as it were instinctively, taking the pulse of the man who would never be far out of his thoughts for the next thirty-eight years.

By the time Voltaire had settled down in Berlin, ten years later (he had arrived there on 27th July 1750), had Cupid’s darts struck? The two certainly talked the talk. Some allowances must be made for the demonstrative amorousness of male friendship in the age of sensibility. But Frederick was homosexual, and Voltaire (who almost certainly had enjoyed sex with men in earlier years) reminds us of this constantly in the Memoirs, in tones that range from the indulgent and complicit (at least one historian thinks he and the King had a real affair) to (much more often) the sly and sardonic. During the first flush of his romance, he was more fulsome: he wrote to his niece that he had been ‘formally given away’ in marriage to the King of Prussia, and that his heart ‘pounded nervously at the altar’... But as the Memoirs relate, there was just too much in common between them, over and above their sex, for the grande passion between philosophe and monarch to last. And Voltaire became increasingly jealous of Maupertuis, whose side Frederick took. Their ‘divorce’ was inevitable.

Oddly touching though it is, the love story between two brilliant, restless, tetchy men is not the only one related in the Memoirs. There is also the love story (always fraught) between the mind that dreams up ideas and the power that enacts them. This is how Voltaire wanted to play it: he was the legislative to Frederick’s executive; perhaps he could do more than just polish Frederick’s French poetry, and even dissuade him from his unfortunate habit of marching off to war. He so wanted to be Plato to Frederick’s Dionysius. But for one thing, as kings go, Frederick, despite being Carlyle’s ‘terrible practical Doer’, was in some ways already quite philosophical enough (even Voltaire, with his watercolour deism, could be – or affected to be – shocked by Frederick’s indulgence for the materialist atheism of La Mettrie) – and in any case, he increasingly treated not Voltaire but his rival Maupertuis as his ‘Plato’ (as Voltaire, with some pique, nicknamed his fellow Frenchman). Nonetheless, the relationship between Voltaire and Frederick seems not just to re-enact the tensions implicit in the idea of the ‘philosopher-king’, but to anticipate, tentatively and uncertainly, a longing for what would later be called, in language neither of them would probably have liked, the reconciliation of theory and praxis. (Frederick can still be seen trotting merrily along Unter den Linden, whistling the Hohenfriedberger March; a short distance away, in the chilly marble of the entrance hall of the Humboldt University, Marx’s Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach still gleams in dull gold.)

And there is yet another fraught relationship running through the Memoirs: that between French and German culture. Given the francophilia of Frederick, this produces ironic effects of chiasmus and reflection: at times we are in a vast Hall of Mirrors (which, after all, is where modern Germany was officially to come into being in 1871). Voltaire goes from France to a Prussia whose king is intent on copying French culture; what Voltaire finds in Potsdam is, on a smaller but still impressive scale, Versailles. Frederick speculated that the German language might conceivably develop from boorish peasant grunting into something more civilised, but he far preferred French: Voltaire’s attitude to German is best expressed by the names he invented for German characters (Baron von Thunder-ten-tronckh) and places (Valdberghofftrarbk-dikdorff) in Candide. Both of them, convinced that the language of philosophy was French, would have been bemused by what might be called the philosophical tyranny of Germany over France during the last couple of centuries: the Left Bank is watered by the Rhine as much as by the Seine, students in the Sorbonne track Being through the dark thickets of Heideggerean etymontology, and the philosophical revolution wrought by one of Frederick’s subjects, Immanuel Kant, still sends shockwaves through the seminar rooms of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. It’s not all a one-way story: Nietzsche (who dedicated Human, All-Too-Human to Voltaire) scorned the culture of the Second Reich and wished he had written Also sprach Zarathustra