Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BroadStreet Publishing Group, LLC

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

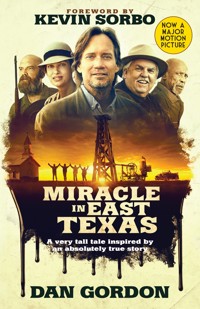

Every saint has a past. Every sinner has a future. Based on the movie Miracle in East Texas, this is the story of two aging, fast-talking hucksters: Doc Boyd and Dad Everett. These hard-luck con men make their living swindling widows during the Great Depression by selling them shares in sham oil wells. The truth is that they're selling hope and more romance than the widows they swindle have ever known. Once they've sold about a thousand percent of these fraudulent shares, they declare the well a dry hole and head for greener pastures. Then, miraculously, every lie they tell comes true. They hit not just an oil well but the richest strike in North America. They should cap the well, declare it a dry hole, and make their getaway. But then they would have to walk away from being honest oilmen for the first time in their larcenous lives. What follows is funny and poignant, romantic and inspiring. This tall tale inspired by an absolutely true story comes from a time when bums became billionaires and sinners became saints.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 349

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BroadStreet Publishing® Group, LLC

Savage, Minnesota, USA

BroadStreetPublishing.com

Miracle in East Texas: A Very Tall Tale Inspired by an Absolutely True Story

Copyright © 2023 Dan Gordon

9781424558827 (softcover)

9781424558834 (ebook)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All Scripture quotations are taken from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®). Copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Stock or custom editions of BroadStreet Publishing titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, ministry, fundraising, or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected].

Cover and interior by Garborg Design Works | garborgdesign.com

Cover design adapted from movie poster created by Barbara Marquis-Adesanya in conjunction with Obviously Creative | [email protected]

Printed in the United States of America

23 24 25 26 27 5 4 3 2 1

For Sam Cohen:

Cattleman, pioneering aviator, sailor, geologist, and master of all matters petroliferous.

The world is a much duller place without him.

Contents

Foreword

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

About the Author

Foreword

When Denzel Washington was interviewed on the Charlie Rose show about his now-classic movie The Hurricane, he said, “They presented that script to me, Dan Gordon’s script…And I said let’s go. Let’s go!”

Some of the best actors in the business have had that same reaction when reading a script by Dan Gordon: Kevin Costner, Gene Hackman, Sir Ben Kingsley, James Earl Jones, Forest Whitaker, Kevin Bacon, Gary Oldman, James Garner, Michael Landon, Dennis Quaid, and yours truly, to name a few.

There’s a reason for that. Dan Gordon is a storyteller who creates characters who are not only real but almost always involved in an existential struggle between the better and worse angels of themselves. They are not cardboard heroes. They are flawed. In other words, they are like most of us. They are struggling to find or resist faith and, like us all, are in need of grace.

Whether it’s Kevin Costner’s brooding portrayal of Wyatt Earp or Denzel Washington’s rage-filled Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, who ultimately realizes, “Hate put me in prison. Love’s gonna bust me out,” Gordon’s characters are in search of their better selves. They are all, at one point or another, going to reach out for God’s redemptive love—sometimes despite their best efforts not only to avoid that love but also to deny it or, like Jonah in the Bible, run away from it if they can.

And that brings us to Miracle in East Texas, the movie based on Dan’s screenplay, which I had the pleasure of directing, and its protagonist, Doc Boyd, whom I had the equal pleasure of portraying.

Miracle in East Texas is the story of two fast-talking huck-sters: Dr. Horatio Daedalus Boyd and Dad Everett. These two hard-luck con men make their living swindling widows during the height of the Great Depression. That puts them certainly in the bottom half of the moral barrel. But then, by what can only be described as the grace of God, every lie they tell begins to come true. What follows is funny and poignant, romantic and inspiring.

It is the story of two scalawags who, despite their best or worst intentions, find those better angels inside them. It is the rollicking story of a time of miracles: the East Texas oil boom of the early 1930s, a time when bums became billionaires and sinners became saints. It is a tall tale inspired by an absolutely true story. If you enjoy the read half as much as we enjoyed making the movie, you’re in for a good time!

Actor, director, producer

Chapter 1

The only thing they knew about Tanner Irving Jr. was that he was an old Black man and one of the only living people who actually remembered what had happened in Cornville, Texas, in the year of our Lord 1930.

“Is he in a home or somethin’? I mean, like, does he drool? I mean, do we even know if the guy can talk?” asked young Matt Ingersol.

Not that he actually cared. For him, there were only two important things about this school assignment. One was that, even though he had just turned sixteen and had recently gotten his license, he was actually getting to drive not the family Subaru but what seemed to him like an oddly majestic Ford Econovan, which contained all their video and sound equipment. The second thing was the fact that, since he was an AP sophomore taking a senior class in state history, he had been teamed up with Denise Waters, a stunning almost eighteen-year-old senior with a smile that could light up ten rooms. Her mother had been a former Miss Puerto Rico in the Miss Universe contest, and her father was a movie star–handsome sports commentator who had played six seasons in the NBA. She was the veritable “Girl from Ipanema”—tall and tan and young and lovely—and every boy at Marcus Hill Christian Academy had a crush on her. And he, Matt Ingersol, was the guy who got to sit beside her, cruising in the Econovan.

There were only a few slight impediments standing in the way of Matt Ingersol’s courtship of Denise Waters.

First, Matt had recently experienced two physiological changes. He had grown from five foot ten to six foot three in less than half a year. His shoe size had gone from a nine and a half to a thirteen. He was not used to the size of his new feet and, therefore, continuously tripped over them. He also tripped over furniture, electrical wires, garden hoses, and any of the other seemingly ordinary accoutrements of everyday life that, for Matt, had become the equivalent of a Navy SEAL’s obstacle course.

The second thing that had occurred was that his voice had suddenly dropped from an almost castrato-like, high-pitched teenage squeak to a Johnny Cash basso profundo, and his vocal cords had not yet become accustomed to their new and lower-pitched tuning. Thus, he would occasionally and uncontrollably emit a sound not unlike that of a duck with irritable bowel syndrome.

Put the two physiological changes together and you had a sixteen-year-old Barnum and Bailey clown in floppy shoes three sizes too big and a honker Harpo Marx would have envied, except that it was located in his throat, not attached to a squeeze bulb on his hip.

Thus, the possibility of actually impressing Denise Waters, upon whom he, like every other boy at school, had a crush, was almost nonexistent.

Unfortunately for young Matt, when he asked, “Do we even know if this guy can talk?” he honked instead of pronouncing the last word of the sentence.

“Do we even know if he can what?” Denise asked.

“Taaalk!” Matt said, honking once again.

“Talk?” Denise asked. “Were you trying to pronounce the word talk?”

“Speak,” Matt said, searching for any other set of phonetics that would not produce the dreaded sound.

“Ah,” said Denise. “Do we know if he can speak. Well, whether he can or he can’t, my guess is he doesn’t honk.”

When they arrived at Tanner Irving’s farm, Matt navigated the long and elegant driveway leading up to the equally elegant home that sat atop a small hill, surveying the lush farmland below. It fell to Matt to manfully stride up to the front door and make the introductions.

He rang the doorbell and waited for what he assumed would be a live-in caregiver to greet them and invite them in. Instead, the door opened, revealing Tanner Irving Jr. He had a corncob pipe clenched between his teeth. Mr. Irving opened the door just the tiniest bit, only seeing Matt and not Denise, who stood off to the side.

“Yes?” he asked, looking impatiently at Matt, as if the boy had come to sell him unwanted magazines or cheap chocolate for a high school fundraiser.

“Uh. Uh, Mr. Irving?” Matt said, honking on the last syllable.

“Boy, did you just honk at me?”

Matt’s face reddened. He cleared his throat. “Are you Mr. Irving?”

“That’s me,” said the cantankerous centenarian. “And who are you?”

“Um, I’m Matt Ingersol. I’m from Marcus Hill Christian Academy.”

“Not interested. Good day.” He closed the door unceremoniously in Matt’s face.

Matt looked down at his shoes as if they somehow could instruct him as to what to do next. Alas, they were just shoes and provided him no counsel. Thus abandoned by his footwear, he rang the doorbell again.

After a few moments the door opened, and Irving once again appeared, smoking his corncob pipe like an angry locomotive belching clouds into a pristine sky. Even at close to one hundred years old, he was still strikingly handsome.

“I’m Mr. Irving, and you’re from the Marcus Hill Christian Academy. We’ve established that. We’ve also established that whatever you’re selling, I’m not buying.”

“Uh, Mr. Irving,” said Matt, beginning to feel flop sweat beading up on his forehead and dripping down, staining his shirt. “I’m not selling anything.”

“Well, I already donate to the University of Texas and LSU. Those are the only scholarships that I give, and all my other charitable giving is already spoken for. So I wish you well. Vaya con Dios, Godspeed, and adios.”

He closed the door once again, for emphasis.

Matt looked at Denise.

Denise looked at Matt and, with an unmistakable expression that gave an unmistakable message, said, “Ring the doorbell again, you wuss.”

Matt rang the doorbell again.

Once again, the door opened, and Tanner Irving Jr. appeared, clouds of smoke swirling about his head like that of a sacrifice recently made to a pagan god. Mr. Irving had clearly had enough of this boy.

“Son, I’m trying to watch a ball game. Some people might admire your persistence, but I just find it annoying. Now, you ring this door one more time, and I’m coming out with a shotgun.”

So saying, Tanner Irving Jr. turned on his heel and, one might even say sprightly for a man of his advanced years, prepared to withdraw into the inner sanctum of the home he considered not only his castle but, during football season, the very sanctum sanctorum of his big-screen plasma temple to southern collegiate gridiron.

“Mr. Irving, please,” said Denise, stepping forward into Tanner Irving’s line of sight with the same honeyed charm with which she, to that day, wrapped her six-foot, six-inch former NBA star father around her finger. “My name is Denise Waters.”

She let a little more southern drip into her accent, with just the proper hint of girlish flirtation, like a subtle scent of perfume in a veritable ocean of respect. “We’re here to film the interview with you for the documentary we’re making for our Texas history class.”

Tanner Irving, if not mollified, at least slowed the tactical retreat in which he was previously engaged. With his eyebrows raised, his look was that of a man his age who was trying to mask the fact that he may have temporarily forgotten not only who you are but also what he was just about to do before you interrupted him.

Denise Waters recognized the look. It was the same expression she had seen many times on her own grandfather’s face, the one that both broke and touched her heart to know what the passing of time can do to the mental acuity of those you love the most. She decided that the only way to break through to the once razor-sharp mind of Tanner Irving Jr. was to deck it with southern charm.

“We’ve driven all the way from Dallas, sir,” she said, almost blushing with modesty.

Tanner Irving looked from her to the gawky teenage boy standing beside her.

“Your classmate’s a lot sharper than you are, son.” He looked at Denise, then shot a not-so-kindly word of advice back to Matt. “You should have let her do the talking from the get-go.”

With that, he dismissed young Matt entirely and turned to Denise, who reminded him so much of his own granddaughter.

“What documentary?” he asked, with as stern an attitude as he could muster, all the while feeling himself being wrapped, ever so subtly, around that little finger.

“It’s about Doc Boyd and Dad Everett,” said Denise, “and everything that happened out in Cornville back in the thirties.”

Those words brought a snap of electricity to the air, shattering the mist around the thoughts of a man who had outlived even his own memories. It brought Tanner Irving back in an instant, with a clarity that startled him, to his own youth, to days when no one on earth was as strong as his father or as fleet of foot as that man’s ten-year-old son running across the endless flatland for the sheer joy of running.

“Cornville? East Texas?” he said, turning back to Matt accusingly. “Why didn’t you say so? You’re late, aren’t ya? Weren’t you supposed to be out here this morning?”

Now it was Matt’s turn to be lost in the fog of the old man’s jumbled thoughts. “Ah…” he stuttered. “No, we were supposed to—”

But Denise, yet again, came to the rescue. She was no stranger to the kaleidoscope of memory and illusion that tumbled through an old man’s thoughts. “Yes, we were,” she murmured, opening the tap of southern molasses just a wee bit more. “And we’re terribly sorry for the inconvenience, but we got stuck in traffic on the interstate.”

Tanner Irving Jr. smiled at the young girl. She was the spitting image of his great-granddaughter, the apple of his eye, now finishing her final year of law school, which he had happily paid for with his part of the bounty that remained from that legendary time when, in the midst of the hopelessness and despair of the Depression and dust bowl, it seemed as if giants roamed the earth.

“You gotta learn how to stretch the truth, son,” he said to the boy. “This girl has a talent for it.” The last part he said with no small amount of appreciation. For, in truth, no one had more admiration for one who could test the elasticity of fact than Tanner Irving Jr. He had the privilege of seeing the two best flimflam men who ever bamboozled the locals of Oklahoma and East Texas, clinging as these two men did to each impossible test of the fine line between fact and fiction, as children believe that Santa is a plate of cookies away from leaving them ponies.

“Doc Boyd and Dad Everett. Sure. You bet. Where we gonna do this…Hollywood opus?”

Victory! young Matt thought. He was now young Spielberg, about to turn a point-of-view shot into a killer shark rising menacingly from the depths toward a girl innocently swimming across the surface of the water. “Well,” he said, “we thought maybe in your living room, with all your memorabilia and stuff.”

And as he said the words, he was lighting the scene in his mind, adding a sepia tone here and a Depression-era black-and-white filter there.

Tanner Irving Jr. had not heard a word he said. “How about right here on the front porch. In this rocker.” So saying, he planted his tall and lanky frame into his beloved rocker, from which vantage point he often gazed not only across the endless stretch of farmland but also at the dimly lit memories that flickered across his mind like the film reel in the picture shows of his youth.

“What a wonderful idea!” Denise Waters said.

But young Matt was not going to surrender his Oscar that easily. “Uh, sir?” he said, as respectfully as a budding auteur could manage. “It’s a little,” he struggled for a word that would not insult the man, “bland, you know? The white backdrop with the white front porch. It needs something to make it pop.”

“Make it pop,” Irving said evenly. It wasn’t a question when he said it. It was a judgment.

“Yes, sir,” said Matt.

“On my porch?” said Irving.

Matt dutifully nodded. “Yes, sir.”

“I’m not big on ‘popping,’” said the old man, with a surprising amount of steel in his voice. “We’ll do it right here.”

“You bet,” said Matt.

With that, he set the Sony α6500 camera on the tripod, put an LED light panel on a stand, pulled out a white pop-up bounce board, and began to toy with the notion of racking focus, anything, anything at all to put his fingerprints as a director upon the frame.

“Ready when you are, Cecil B.,” Irving said.

Matt pressed the record button on the camera and said, “Rolling!” only too aware of the crack in his voice, which he had meant to sound so decisive for Denise’s benefit and which instead came out as more of a mallard in heat.

Denise smiled, the kind of smile that dashes the hopes of young boys with crushes on older girls. She put the slate in front of the camera and said, authoritatively, “Cornville documentary. Tanner Irving Jr. interview. Take one.”

She clicked the slate and moved out of frame. Then, she picked up the yellow legal pad filled with questions she had assiduously assembled from all the written research material at her disposal when suddenly, Mr. Irving said, “We gonna be at this for very long? More than an hour?” He looked back and forth between Matt and Denise.

Matt cleared his throat, hoping to preempt any further croaking noises. “Probably, sir.”

With that, Tanner Irving rose from the rocking chair that creaked along with the floorboards of the porch. “Well,” said Irving, “I’d better hit the john first. Pay my water tax.”

And without another word, he walked back into his house and closed the door, leaving Matt with nothing to do but say, “Cut.”

Chapter 2

“Cornville documentary. Tanner Irving Jr. interview. Take two,” Denise said and snapped the clapboard shut.

“I assume you’re going to ask me the questions, young lady.”

It was not a question. A Tanner Irving Jr. assumption was a statement of fact.

“Yes, sir,” said Denise, dripping honeyed southern charm.

“Good,” said Mr. Irving. “You seem to have a certain”—he waved his hand, searching for the right word—“je ne sais quoi about you I find lacking in young Matt here. What is your name again?”

“Denise, sir,” said young Ms. Waters, looking Mr. Irving straight in the eye, all journalist all the time.

“Okay, Denise, give me your best shot,” said Irving, taking a long draw on his corncob pipe and puffing out a cloud that encompassed him like he was an ebony Vesuvius.

Denise glanced down at her yellow legal pad, carefully engraved with each of the questions she had fashioned the night before. But before she could ask the first one, Tanner Irving Jr. beat her to the punch with, almost word for word, the first question on her list.

“How old was I when I first laid eyes on Dad Everett and Dr. Boyd?”

“Uh, yes!” said Denise. “How old were you when…”

“I got it, baby sister.” He nodded his head, took another draw on the tobacco, and eased himself down into a comfortable memory, which he visited often in the late afternoons while gazing out across the beauty of the farm that had come to be his as a result of that first meeting.

But he wasn’t going to give it up that easily. Let this young journalist think he was searching for it.

“Oh, let’s see. That was more than eighty years ago. I must have been, maybe, nine or ten.”

The truth was, it was more like ninety years ago, but an older gentleman can be excused for shaving a decade or two off his résumé for a comely, young southern girl. “But Boyd wasn’t any doctor.”

“He wasn’t?” Denise asked, in true dismay. In her research, she had found mention of a university degree from a European institution of some repute.

“Not even close,” said Irving. “And his name wasn’t Boyd either. And he wasn’t any kind of geologist. He was eking out a living swindling widows with worthless oil scams. I expect he couldn’t have been much better at that if he had been a real doctor.”

With that, Irving drifted back in his mind’s eye to the first time he had seen Doc Boyd and Dad Everett driving up the country lane in their brand-new, shiny black 1929 Model A Ford convertible. He had never seen a vehicle more magnificent. The spoked chrome wheels caught the glint of the sun and reflected it like mirrors, highlighting the whitewall tires and cream-colored rims. And behind the spare tire, there was a custom-made luggage rack that held Doc and Dad’s trunk like a prized treasure borne aloft by imperial servants. It was a chariot truly worthy of, if not a king, then at least a renowned professor of geology.

When he alighted from the vehicle, Boyd cut a dashing figure in his high-topped, buckled boots that clung to his calves like those of a spit-and-polish Queen’s Own British officer and gentleman. The flared, white, cavalry-like riding breeches highlighted the military effect. Boyd wore a white dress shirt, buttoned up to the top button, and a crushed gray velvet blazer that contrasted the military air with one of an accomplished, cultured, academic gentleman of leisure. Topping off what Tanner Irving Jr. thought was the most exotic apparel he had ever beheld was a dazzling white derby set off with a blue sweatband, around which Tanner could see not even the slightest trace of perspiration.

Dad Everett, on the other hand, created an entirely different impression. He did not so much alight from the gleaming black Model A as he did hoist his massive bulk, not unlike a paddle wheeler off-loading its cumbersome cargo onto the dock. The Model A seemed to sigh in relief, and its springs, unburdened of the weight of the aging wildcatter, rose, like a young gazelle, at least another six inches off the ground.

Dad was a workingman to his core. When he was working on the rigs, he wore brown Carhartt canvas overalls, a dark brown shirt, and a sweat-stained fedora of an indefinite color. It was neither brown nor gray; it simply looked soiled. When he would visit the aging ladies, whom he sometimes referred to as “the widders,” he wore more formal attire—gray slacks, a faded gray shirt, an increasingly tight-fitting blue blazer, and the ever-present fedora. It was difficult to say that he cut a dashing figure; rather, he presented as almost Gibraltar-like, something time-tested, solid, and true.

Where Doc was flamboyant, Dad was rock steady. Where Doc was elegant, Dad had workingman’s dirt under his fingernails, of which anyone could see he was proud.

Denise interrupted Irving’s reverie, asking, “Mr. Irving, did you say his name wasn’t really Dr. Horatio Daedalus Boyd?”

“What’s that?” Tanner Irving Jr. asked, as if reluctant to leave the golden, sepia-hued memories of his childhood, which felt like a most comfortable old pair of overalls.

“Doc Boyd?” Denise asked. “Dr. Horatio Daedalus Boyd? You say that wasn’t his real name?”

“No, his name was Bumstetter, as I recall. Heinrich Bumstetter,” Irving said, remembering the shock he felt hearing the man’s real name for the first time during the infamous trial covered by every newspaper in the land. “Boyd was an alias. And then he was P. L. Dobson, and then, I believe, Arthur Lloyd Carrington Jr. He had a French name or two, I think. Though what they were slips my mind. Peppy La Pew or something like that.”

“Why did he keep changing his name?” Denise asked innocently.

“The man was a serial bigamist,” Irving responded, “and he left a string of heartbroken widows all across the nation’s heartland.” Irving’s gaze drifted upward to the clear blue sky. “I remember a story, in fact, in which Dr. Boyd, mischievous, old scalawag that he was, had to run for his life, carrying his carpetbag, while an irate, overweight husband pursued him across the horizon with a twelve-gauge shotgun, with which he had sincerely intended to ventilate Dr. Boyd’s backside.” He chuckled to himself, his teeth clacking against the pipe in his mouth. “Luckily for Doc Boyd, it was not his first such encounter, and his faithful companion, Dad Everett, had their old, original cream-colored Model A coupe waiting with the door open and the engine running for a quick getaway.” Irving shook his head, half in disapproval, half in admiration. “Happily for Dr. Boyd and unhappily for the irate husband, the latter, while giving chase, caught his foot in a prairie dog hole that brought his bulk crashing down to Mother Earth and harmlessly discharging the buckshot into the prairie grassland.”

He removed a handkerchief from the pocket of his pants and wiped his eyes, still grinning at the memory.

“Horatio Daedalus Boyd was simply the latest in a long line of aliases meant to keep creditors, husbands, and jilted inamoratas from filling his backside with the aforementioned double-aught buckshot.”

Irving leaned forward, looking into Denise’s eyes. “Course, he didn’t start out with the oil scam. He began by selling Dr. Enrique Alonzo’s Miracle Elixir of Life. Much later, in my teenaged years, Doc Boyd showed me photographs of that incarnation. He would stand on a loading dock or train station platform in a white smock, complete with a stethoscope around his neck and a doctor’s reflector around his head. He repeated for me his patter and one particularly amorous adventure.”

Irving cleared his throat and proclaimed, “‘Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls,’ he would say, gathering the crowd around him. ‘You’ve heard it said many a time you can’t put a price on your health. Well, tonight, my good friends, let me tell you right here and now—you can! For only one dollar, one green-back, a mere buck, a screaming eagle, a trifling one hundred pence, you will have the cure for every ailment under the sun, A to Z. Arthritis, bursitis, conjunctivitis, diverticulitis, fibrositis, gastritis, hepatitis, laryngitis, meningitis, nymphitis, and otitis. As a matter of fact, any -itis under the sun will more than meet its match with Dr. Enrique Alonzo’s Miracle Elixir of Life.’

“At that point,” Irving continued, delighted to have an audience, “a not-unattractive, middle-aged housewife piped up and said, ‘Dr. Alonzo? Will the elixir…Well, my husband’s a traveling salesman, and he gets home awful tired. It just seems like he doesn’t have any of the old vim and vigor anymore.’

“At which point Doc Boyd smiled at her and responded, ‘My dear, did you say a traveling salesman?’

“The upshot of which found ‘Dr. Enrique Alonzo’ once again hightailing it across the prairie land, carpetbag in hand, pursued by yet another irate husband armed with a scattergun and the full intent of putting it to use against the good doctor.

“After a number of run-ins with irate customers—and some of their husbands—he was reborn as Dr. Horatio Daedalus Boyd: petroleum engineer, geologist, and world-renowned authority on all matters petroliferous. He and Dad Everett had already been working together for a bit in the Dr. Alonzo years, so it was a natural fit when he left ‘medicine’ for petroleum.”

“But,” said Denise, “I thought you said Dad Everett was a wildcatter and driller.”

“He was,” said Irving. “But he was the unluckiest wild-catter that ever lived. His name was David Henry Everett. But everyone said that the D. H. actually stood for ‘dry hole.’ In late 1900 he was drilling in a little town called Gladys City, Texas. He was sure there was oil there. But after three dry holes, the money to drill a fourth dried up as well. He had to gather round all the roughnecks and say, ‘I’m sorry, boys. But I’m flat busted. And I can’t squeeze another dime out of anyone around here. Pack it in. We’re finished.’ They walked off broken men.

“Two months later, a fellow named Lucas drilled a well less than a football field away from Dad Everett’s. He struck oil at eleven hundred feet. Hit a gusher that blew a hundred and fifty feet in the air and brought in a well that flowed at a hundred thousand barrels a day, in a place called Spindletop.

“After that, Dad drilled at a place called Burkburnett. But the drill bit stuck and broke. It would cost a thousand dollars to get it out. Might as well have been a million. So Dad packed it in. That was 1918. And wouldn’t you know it, a fella came in right behind Dad Everett, fished out the broken bit, drilled down another thousand feet, and hit one of the biggest oil fields in Texas. After that, ol’ Dry Hole Everett was pretty much a joke.

“Well, these two hard-luck stories, Doc Boyd and Dad Everett, teamed up, first with the medicine show and then with the worthless oil wells.”

Denise jotted down notes furiously. During the pause, Matt took the time to rack focus. There was a potted geranium plant on the porch and a bit of wisteria dangling down at the right edge of the frame. He blurred his focus on Tanner Irving Jr. and brought the two flowering plants into sharp focus, thinking how he would highlight the color when he photoshopped the image. But even the budding Spielberg was beginning to get caught up in the magic of the old man’s memories. After all, he wasn’t talking about things he had read in a book. He had actually been there, lived through them, known these men who had so boldly conned their way across the country a century before.

Mr. Irving began to speak again, not so much to the two youngsters as simply reminiscing aloud.

“You cannot imagine,” he said, “not only the physical toll but also the emotional toll of the wildcatter’s life. My father knew them all. And I met them. Doc and Dad were pretty much the last of that breed. Some of my earliest memories were of my father hauling wood out to some wildcatter’s rig. They were all steam powered, and he supplied the fuel for their boilers.

“The physical work was tough, pretty much harder than anything you can imagine. It wasn’t just dawn to dusk. Sometimes it was twenty hours a day. And dangerous too. A drill bit could break loose and go straight through a man working down in the shaft, like Ahab’s harpoon going through a whale. And if you brought a well in, the slightest spark could set off a conflagration like hellfire itself. The explosion would rock the earth, and the flames would seem to reach up into the heavens, and sometimes it took weeks to put out a real oil fire. And there was no small danger in that either. Because usually you did it with dynamite. There were ropes and cables like snakes that could slip loose, catch a man’s leg, or lash him across the face so hard it would almost take his head off.

“But I do believe the emotional toll was even worse. The wildcatter never had a big company behind him. He usually staked everything he knew on nothin’ more than a hunch. Geologists could survey all they liked, but those old wildcatters, they were almost like prophets in the Bible.

“Old Dad Everett used a divining rod. It was a forked stick. And I know he put on a pretty good show for the widders, but he actually claimed to me that that old divining rod would dip when there was oil beneath the earth. A time or two, he said, it nearly yanked him off his feet. I don’t know how much of that was embellishment. Doc claimed to put no stock in it, called him a primitive.

“But that’s what a wildcatter was: part gambler, part diviner, part dreamer, and always a loner, with no place to stay and no one to come home to.

“They’d roll out some rickety old rig sure that this time, they were gonna strike it rich. Sure that this time, the good Lord would smile on them, that one of these days, they’d feel the earth rumble and hear a sound like a volcano about to blow its top off and then see the black gold spout up out of the earth like ol’ Moby Dick himself rising up out of the ocean, blowing not seawater out of his spout but thick, black crude that you could dip a stick into, light up, and burn all night.

“They lived on hopes and dreams, cans of corned beef and cold beans. I don’t believe even cowboys had as tough a life. I know that sodbusters didn’t. After all, if you were a farmer, you had a decent piece of land, you worked hard, planted your seed. With any luck, there was a little bit of rain, and you were sure of a harvest. The only variable was how good a harvest it would be.

“But the earth wasn’t like Lady Luck. Lady Luck was harder than the toughest saloon girl you ever saw in your life. If you had two bucks, you could be sure of a saloon girl’s fidelity for at least an hour. But Lady Luck didn’t care if you had two bucks or two million. She didn’t care if you were Rockefeller or Dad Everett. She bestowed her favors in the most capricious manner imaginable. Whether she’d bear her treasure or not had nothing to do with how hard you worked, how much you prayed or hoped, what you risked, or how you courted her. You could miss her by a foot, and it was as good as a mile.

“And each time, the wildcatter, more than anything else, more than how much he sweat or how much he bet, believed. Believed that, this time, it would all fall into place and he’d finally get it right and hit just that spot where the earth would explode and bathe him, shower him, in good fortune.

“It wasn’t just drill bits that got broke, nor legs, nor arms either. It was men’s hearts and spirits that broke, and that was the saddest thing of all. A man could get by with a bum leg. Broken arms heal. But you break a man’s spirit, and it pretty much doesn’t matter what his body can do after that.

“So old Dry Hole Everett, I guess, after Spindletop and Burkburnett, just gave it up. Gave up hoping and took to being nothin’ but a two-bit, tinhorn flimflam man. That was a step down for him and a mighty steep one to boot.

“But I do believe Doc Boyd reveled in it. I think he may have believed half the lies that he told. I don’t know that he rightly swindled those widows as much as he convinced himself that maybe he did love ’em. That maybe, somewhere in the back of his mind, he bought his own snake oil and took a swig, thinkin’ it would cure what ailed him too.”

Both of the teens listened without making a sound, as if they’d been eavesdropping on a private, perhaps sacred conversation. The old man grew quiet as well. The only sound was his rocker and the boards creaking on his front porch and the occasional sucking sound as he took another draw on the pipe.

Finally, Denise broke the silence and said, simply because she couldn’t think of anything else to say, “So Doc Boyd didn’t have a degree of any kind?”

“What’s that?” Tanner asked, still lost in the reverie of memories of the flimflam men, who were fools or heroes or both, who more often than not had nothing but torn overalls and blackened faces from woodburning boilers that never seemed to wash completely away.

“Dr. Boyd,” Denise repeated. “I read that he had a degree from the University of Heidelberg.”

“He did have a degree. It was a beautiful diploma. I remember seeing it myself. The only problem was it wasn’t issued by any university, let alone the University of Heidelberg, though it was quite beautiful to behold, bedecked with ribbons and sealing wax. And as worthless as anything else connected with Doc and Dad.

“See, what these two old rascals realized is that while they weren’t much good at actually finding or drilling for oil, they both possessed an unusual facility for convincing people that they could do just that.

“Their Model A would pull up in front of a clapboard farmhouse. Doc and Dad would pile out. Doc cut the romantic figure in those beautiful, shining, high-top brown boots with the buckles on the sides and those flared cavalry pants. I’ll swear, the only thing he lacked was a riding crop to smack against those boots, like one of those German silent flicker movie directors. You probably never saw one of them, but when I was a boy, they looked like the most glamorous creatures on earth. Smacked that riding crop against their boots, and men jumped! That’s how Doc looked, like something out of a silent movie. He was a tall man and, as the Good Book says, ‘ruddy and handsome in appearance.’

“He had, as I recall, a long leather map case. You don’t see those anymore. But beautiful craftsmanship. Hand-tooled leather. Brass brads down the side and a leather cap that strapped down to it. And when he unfastened that strap and lifted the cap, he’d pull out the most magnificent things you ever did see: charts and petroleum reports. Geological surveys.

“And ol’ Dad, well, he would haul himself out of that Model A with a grunt and a groan and take that old divining rod. He wouldn’t pay any mind to Doc and his charts. He’d just set off across some stranger’s dirt-poor farm or ranch, holding that divining rod out in front of him, waiting for the ‘earth’s magnetism’ to overcome him like the Holy Spirit at a Pentecostal tent revival.

“Now the first thing you needed in this kind of a scam was some farmer who sat on a dusty, worthless, hardscrabble farm from which even the most diligent hand could barely scratch out an existence. And folks listened because what Doc and Dad were selling wasn’t oil. It was hope.

“They started off in Oklahoma. I remember Doc Boyd telling me about it in later years, regaling me with stories so convincing that it was as if I had been there myself and seen it all…”

Chapter 3

There was a spinster of a certain age, Miss Classafay Vaudine. She stepped out of the ranch house wearing pants like a man and a Stetson to keep the sun off. She worked that place, just her and one ranch hand, all by herself. She was tough as nails, her skin browned and dried out like cracked leather from sun and wind and dust. She lived a hard life. You kids never saw anything like it, but I surely did. Lived it too.

I could tell she had been what men called a handsome woman in her youth, but that youth had been short-lived and worn away by the elements of a country that didn’t allow for youth, that turned folks old before their time.

“You! You, there!” she shouted at Doc and Dad.

Now Dad looked as if he were in a kind of trance, concentrating on the vibrations welling up from the earth through his divining rod and into his very bones. As for Doc, he looked like a silent movie star with that beautifully leather-booted foot up on the running board and his geological chart spread out on the hood.

“With you momentarily, my good woman,” he said, his eyes glued to the geological survey, as if he had seen something as rare as eggs laid by tigers.

“First of all,” said the mistress of the house, “I am not your good woman!”

“I beg your pardon, madam,” Doc replied, touching his fingers politely to the rim of his white derby.

“I’m not a madam neither. I’m a miss, if it’s all the same to you.”

Doc glanced up from the chart, then gazed upon her as if she were Aphrodite herself, risen from the sea. “Unmarried?” he declared. “Is there some ocular affliction in the male species of these parts of which medical science is unaware?”

“In English,” the spinster demanded.

Doc Boyd boldly took a step toward her and said, “Are all the men in these parts blind to leave such a blushing rose as this unplucked?”

“Mister, you see that outhouse over there?” she said, pointing at the slat-boarded outbuilding with the half-moon delicately carved into its door that hung by one rusty hinge.

“Yes, ma’am. I mean, miss. I do.”

“There’s a Sears and Roebuck catalog in there, and I get everything I need for this place from them. So whatever you’re selling, I ain’t in the market.”

“My good madam…I apologize. Miss…”

“Vaudine. Miss Classafay Vaudine.”

“Miss Vaudine,” replied the dashing figure in the flared riding breeches, who gallantly doffed his white derby as a sign of respect for the fairer species, “I am not here to sell anything. I am here simply in the interest of science.”