Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lola Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

In this book, William Mitchell and Warren Mosler, original proponents of what's come to be known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), discuss their perspectives about how MMT has evolved over the last 30 years. In delightful, entertaining, and informative way, Bill and Warren reminisce about how, from vastly different backgrounds, they came together to develop MMT. They consider the history and personalities of the MMT community, including anecdotal discussions of various academics who took up MMT and who have gone off in their own directions that depart from MMT's core logic. A very much needed book that provides the reader with a fundamental understanding of the original logic behind 'The MMT Money Story' including the role of coercive taxation, the source of unemployment, the source of the price level, and the imperative of the Job Guarantee as the essence of a progressive society – the essence of Bill and Warren's excellent adventure. The introduction is written by British academic Phil Armstrong.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 521

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

William Mitchell & Warren Mosler

Modern MonetaryTheory

Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure

Copyright © Lola Books 2024

www.lolabooks.eu

This work, including all its parts, is protected by copyright

and may not be reproduced in any form or processed,

duplicated, or distributed using electronic systems without

the written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © The Authors 2024

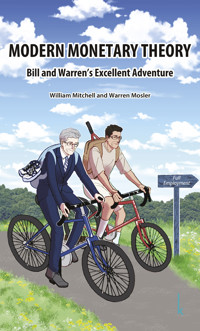

Cover drawing kindly provided by Mihana, who a Japanese

Manga artist. Bill and Warren are very grateful to receive her

excellent work. You can find her at https://x.com/mihana07/

Printed in Spain by Safekat, Madrid

ISBN 978-3-944203-72-0

eISBN 978-3-944203-82-9

Original edition 2024

DEDICATIONS

BILL

Dedicated to the millions of unemployed and their families who have been treated as fodder by policy makers around the world in their misguided attempts to advance the profit interests of the wealthy.

WARREN

Dedicated to all the MMT activists who have both advanced the cause and motivated us to keep fighting the good fight?

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

WILLIAM MITCHELL

Bill is a Professor of Economics and is the Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CofFEE) at the University of Newcastle, Australia. He also is the Docent Professor in Global Political Economy at the University of Helsinki and Visiting International Professor, Kyoto University. He is one of the founders of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

He is the author of various books, including Eurozone Dystopia (Elgar, 2015), Reclaiming the State (Pluto, 2017), Macroeconomics - (with L.R. Wray and M. Watts, Bloomberg, 2019). He has published widely in refereed academic journals and books and regularly is invited to give Keynote conference presentations in Australia and abroad.

He has an established record in macroeconomics, labour market studies, econometric modelling, regional economics and economic development. He has received regular research grant support from the national competitive grants schemes in Australia and has been an Expert Assessor of International Standing for the Australian Research Council. He has extensive experience as a consultant to the Australian government, trade unions and community organisations, and several international organisations (including the European Commission; the International Labour Organisation and the Asian Development Bank).

His daily blog is one of the leading economics blogs in the world.

WARREN MOSLER

Warren is an American economist and theorist, and one of the founders of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Presently, Warren resides on St. Croix, in the US Virgin Islands, where he owns and operates Valance Co., Inc. An entrepreneur and financial professional, Warren Mosler has spent the past 40 years gaining an insider’s knowledge of monetary operations. He co-founded AVM, a broker/dealer providing advanced financial services to large institutional accounts and the Illinois Income Investors (III) family of investment funds in 1982, which he turned over to his partners at the end of 1997. He began his career after graduating from the University of Connecticut with a B.A. in Economics in 1971 and has been deeply involved in the academic community, giving presentations at conferences around the world and publishing numerous articles in economic journals, newspapers, and periodicals.

In addition to his work in the field of economics, he developed – and later sold – his own automobile line, Mosler Automotive, responsible for producing the Mosler MT900 and the Consulier GTP. He also designed his own catamaran that is lighter, faster, and more fuel-efficient than other models.

Mosler is the author of “The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy” that has been translated into Italian, Polish, Russian, Arabic, and Spanish.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

1 THE JOURNEY BEGINS

2 TWO PATHS

ADVENTURE NOTES

WILLIAM MITCHELL

WARREN MOSLER

3 THE TWO PATHS MEET

ADVENTURE NOTES

THE POST KEYNESIAN THOUGHT E-MAIL LISTSERV

EXPLORING THE PKT ARCHIVES

CONCLUSION

4 MODERN MONETARY THEORY (MMT) 101

ADVENTURE NOTES

INTRODUCTION

THE EMERGENCE OF FIAT CURRENCIES

MMT AS A LENS

THE MMT MONEY STORY AND SEQUENCE

LET’S DO SOME ARITHMETIC

UNDERSTANDING THE CONSTRAINTS ON GOVERNMENT SPENDING

HOW DOES MMT HELP US UNDERSTAND THE REAL-WORLD ECONOMY

HOW ARE YOU GOING TO PAY FOR IT?

THE CAUSE OF MASS UNEMPLOYMENT

GOVERNMENTS DO NOT SAVE

ALL SPENDING GROWTH AT MARKET PRICES CARRIES AN INFLATION RISK

WHAT IS THE T IN MMT ABOUT?

THE MINSKY DIVERSION

5 THE JOB GUARANTEE – HISTORICAL CONTEXT

ADVENTURE NOTES

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT – THE 1970S ECONOMIC MALAISE SPAWNS AN IDEA

6 THE JOB GUARANTEE – BASIC PRINCIPLES AND ISSUES

ADVENTURE NOTES

WHAT IS THIS CHAPTER ABOUT?

THE UNEMPLOYMENT BUFFER STOCK APPROACH

EMPLOYMENT BUFFER STOCKS

THE JOB GUARANTEE BECOMES AN ADDITIONAL AUTOMATIC STABILISER

INFLATION CONTROL UNDER THE JOB GUARANTEE

THE NAIBER

WOULD THE NAIBER BE HIGHER THAN THE NAIRU?

THE WOOL PRICE STABILISATION FAILED – SO WHY WOULDN’T THE JOB GUARANTEE FAIL TO?

THE JOB GUARANTEE FLATTENS THE PHILLIPS CURVE

7 A LETTER TO THE MINISTER

BOONDOGGLING AND RAKING

THE JOB GUARANTEE PROPOSAL GOES TO THE AUSTRALIAN MINISTER OF EMPLOYMENT

THE MINISTER REPLIES AND DEMONSTRATES A FAILURE TO UNDERSTAND THE CURRENCY HIS GOVERNMENT ISSUES

JOB GUARANTEE VERSUS A BASIC INCOME GUARANTEE

THE JOB GUARANTEE AS AN EVOLUTIONARY FORCE

WARREN AND THE JOB GUARANTEE

WARREN – PROMOTING THE JOB GUARANTEE AS A TRANSITION JOB

8 THE FULL EMPLOYMENT FISCAL DEFICIT CONDITION

ADVENTURE NOTES

FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY IS DEFINED IN RESOURCE RATHER THAN FINANCIAL TERMS

THE FULL EMPLOYMENT FISCAL DEFICIT CONDITION

AUTOMATIC FISCAL STABILISERS

CONTEXT MATTERS

FULL EMPLOYMENT FISCAL DEFICIT CONDITION

9 CENTRAL BANKS AND ALL THAT

ADVENTURE NOTES

THE CONSOLIDATED CENTRAL BANK AND TREASURY

INTEREST RATES

BANK RESERVES AND INFLATION

THE ROLE OF BANK DEPOSITS IN MMT

CAN CENTRAL BANKS GO BROKE?

ARE CENTRAL BANKS INDEPENDENT?

10 INFLATION AND MONETARY POLICY – CENTRAL BANKS GOING ROGUE

ADVENTURE NOTES

THE BRAVE NEW NAIRU WORLD – THE WORST OF THE WORST!

BRIEF RECAP FROM CHAPTER 9

WHY MIGHT THE IMPACT OF INTEREST RATES VARY ACROSS NATIONS?

WHAT ABOUT THE CURRENT INFLATIONARY PRESSURES?

WHICH IS WHAT HAS HAPPENED

THE ROGUE CENTRAL BANKS

11 MMT AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE

ADVENTURE NOTES

A FOCUS ON REAL RESOURCES

UNDERSTANDING TRADE AND FINANCE

SUSTAINABLE POLICY SPACE FOR A TRADING NATION

IS FISCAL POLICY CONSTRAINED BY THE BALANCE-OF-PAYMENTS?

OTHER TRADE DEFICIT ISSUES

THE PLIGHT OF LOWER INCOME NATIONS AND INDUSTRY POLICY

12 MMT BARBARIANS ENTER THE GATES OF CANBERRA

ADVENTURE NOTES

AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT ANNOUNCES IT DOESN’T HAVE ENOUGH OUTSTANDING DEBT!

FINANCIAL STABILITY AS A PUBLIC GOOD

THE PURPORTED BENEFITS OF COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT SECURITIES ISSUANCE

MANAGING FINANCIAL RISK

PROVIDING A LONG-TERM INVESTMENT VEHICLE

IMPLEMENTING MONETARY POLICY

PROVIDING A SAFE HAVEN

ATTRACTING FOREIGN CAPITAL INFLOW

REDUCED COST OF CAPITAL

THE REAL ECONOMIC COSTS OF ISSUING GOVERNMENT DEBT

FURTHER THOUGHTS

13 JAPAN – THE MMT LABORATORY

ADVENTURE NOTES

THE IRONY OF IT ALL

JAPAN CONFOUNDS THE MAINSTREAM MACROECONOMISTS

ARE THEY ’DOING’ MMT OR WHAT?

THE REPEATING SALES TAX MISTAKES

BANK OF JAPAN HOLDS ITS NERVE WHILE THE REST OF THE WORLD HIKED RATES

THE CURRENCY IS DEPRECIATING – MMT IS OBVIOUSLY WRONG!

THE MONETARY INSTITUTIONS ARE THE SAME – BUT CULTURE DICTATES THE CHOICES MADE

14 A CONVERSATION WITH WILLIAM MITCHELL AND WARREN MOSLER

ADVENTURE NOTES

REFERENCES

PREFACE

Over the years I have come to appreciate the truth of the adage, ‘people love stories.’ I started studying economics in 1976 but for the next three years I encountered few engaging storytellers amongst the economics faculty. I left the University of Hull in 1979, having enjoyed my studies but largely uninspired by the subject. Moving forward to 1983, I reengaged with economics and studied for a master’s at the University of Leeds. There I met my first real economics storyteller, Dr John Brothwell. I enjoyed his approach; he was full of passion and covered the board with chalk and, surprisingly, went on to say he didn’t think much of the diagrams, personally (ISLM took the brunt of his ire).

Brothwell introduced me to a battle within economics; the mainstream who didn’t understand the economy versus radical economists who (presumably) did. The first group were the only people I had studied until I met Brothwell (apart from Keynes, who at the time was laughed at by its leading members). The radicals were led by the man whose work he admired most, US economist Paul Davidson, and there were others whose work he recommended, especially an American who had moved to England, Victoria Chick. These radicals had a group name, ‘the Post-Keynesians’ (sometimes with a small ‘p’, sometimes with a big ‘P’, usually, but not always, with a hyphen). These Post-Keynesians were fighting a backsto-the-wall struggle with the mainstream (Brothwell called the enemy the ‘neo-classical-Keynesian synthesis’ or simply, the ‘synthesis’, which somehow made them sound more villainous).

The mainstream were in control of the economics establishment and exerted a powerful influence on policy despite the fact they couldn’t explain the functioning of the economy. They were well-rewarded for this failure. On the contrary, the Post-Keynesian outliers could explain how the economy worked. This was powerful stuff, many of the unanswered questions I had during my first degree were cleared up (not all – but it was a great start). At the time, I had assumed my lack of understanding of the economy was down to me but, apparently, it wasn’t all my fault. The models had been wrong. Brothwell told me a story; an economics story, an interesting story and one which opened my eyes. I was now on board with the Post-Keynesian struggle – I wrote my master’s dissertation on Post-Keynesian theory, and Davidson and Chick were my leading characters. I then entered a hiatus with economics which lasted around 20 years, but the onset of the global financial crisis and the resurgence of interest in so-called ‘heterodox economics’, including the work of my Post-Keynesian mentors prompted my return to active engagement.

However, the more I looked into Post-Keynesianism the more I acknowledged that it didn’t quite answer all my questions. Perhaps nothing could? Then, in 2010, when searching for Davidson on YouTube, I came across Warren Mosler. I started emailing Mosler with questions which he invariably answered in a sharp and direct way. He was intriguing from the outset and I was fortunate enough to be able to meet him in England and spend a day with him. I discovered a storyteller par excellence. He is a true polymath, highly intelligent, yet kind and modest – his use of tales was both amusing and memorable in equal measure.

In our early conversations, Mosler talked about an Australian academic – a prodigious writer, called Bill Mitchell – who wrote a highly acclaimed MMT blog. I checked out the blog and was immediately struck by Mitchell’s ability to tell stories about history, using his remarkable depth of knowledge of economics in general, and of MMT in particular, to shed light on events. I first met Mitchell at a Gower Initiative for Modern Studies event in Brighton and have been fortunate to interact with him on many occasions since. I have come to appreciate that Mitchell is also a man of many parts, a dedicated and leading academic, musician, surfer, lover of mathematics. He also admits to being rather obsessive, maintaining an intense focus on the projects he undertakes and is highly competitive by nature as befits a sportsman.

As a Christian and a socialist I draw inspiration from R.H. Tawney and Tony Benn, amongst others. I am fascinated by what drives people. Spending time with Mitchell reveals his motivation is based on his strong sense of justice. He is profoundly influenced by his humble working-class roots and is always deeply concerned about the effects of economic policy on those least able to fend for themselves. He is a staunch supporter of progressive left-wing politics and is a tough-as -they-come socialist. I admire Mitchell’s politics and respect the fact he never shies away from asking hard questions and challenging accepted opinion.

As a former Wall Street trader, Mosler is an unlikely staunch advocate for progressive thinking and policy. Nevertheless, that’s just what he is; he maintains a deep concern for the community around him – a concern which is not merely passive. His is a life of actively helping people. Mosler came to realise what could be achieved if people understood what he understood; that for countries with their own currencies under floating exchange rates, it is the availability of real resources and political will, not finance, that constrains governments. With MMT insights on board, progressive policy previously deemed desirable but unaffordable could be shown to be fully affordable and could not be dismissed on monetary grounds.

The collaboration between Mosler and Mitchell has been highly effective. They have both worked tirelessly, challenging the incorrect mainstream narrative, with the ultimate goal of making people’s lives better. They both recognise that to achieve this aim, it is crucially important to have a consistent body of work that provides the economic rationale to explain why progressive policy can work. As MMT has gained attention, it has faced increasing attack from the economics and political establishment. This is inevitable as MMT is increasingly seen as a realistic threat to the neoliberal mainstream view that dominates current thinking.

In the current climate, telling the real story of MMT is becoming ever more important; where it came from, what it is really about and what it can provide. Setting the record straight is vital and there are no two people better qualified for this task than Warren Mosler and Bill Mitchell.

Dr Phil Armstrong

The Gower Initiative for Modern Money Studies (GIMMS) London

May 2024

1 THE JOURNEY BEGINS

Look after unemployment and the budget will look after itself

John Maynard Keynes (Keynes, 1978: 150)

There is no possible justification whether rooted in ‘efficiency’ concepts and/or morality concepts for the government to deliberately engineer and sustain mass unemployment when it has the policy tools to immediately reverse course and maintain full employment. Yet, that is what they do. Every day. They justify deliberately rendering workers jobless by claiming that they do not have the financial capacity, or that it would be inflationary, or that the bond markets will stop buying their debt, or that the value of the currency will crash, or that … A multitude of supporting fictions are trotted out each day in the media by the politicians, business leaders, and academics. The population see this conga line of ‘experts’ on the TV or in the newspaper predicting that the sky will fall if the unemployment rate falls below their presumed minimum, condemning millions to lives of involuntary unemployment, and the rest to a reduction in their economic well-being. But when the government outlays billions to buy military equipment or bail out private banks that have fallen over themselves as greed surpassed acumen, these economists say nothing. The only question is whether it’s out of ignorance or malice, with the former perhaps the more damning. It’s a sordid pantomime that plays out every day and there seems no way out of the nightmare.

But there is some hope. This is the story about Bill and Warren devoting the last several decades to breaking through the disinformation and promoting the correct way of understanding the monetary system and the broader macroeconomy. They have been supported by other academics who subsequently joined the struggle and adopted the Modern Monetary Theory (hereafter MMT) framework in their own work. Together they share the ‘MMT Money Story’ recognising government as the direct cause of unemployment, immediately responsible for its continuation, and immediately capable of shifting to full employment policy, which is the focus of this book. As Warren once said, the only thing preventing full employment and price stability is the space between our ears.

The book is about Bill and Warren’s journey down the MMT path. It is a bit different to other more conventional books in that the pedagogic material is interspersed with personal anecdotes or ‘Adventure Notes’ to provide context, and historical records to establish provenance, and more. The Adventure Notes are also there to give the reader a respite from the economics – a sort of light interregnum. After all, we want the reader to finish the book!

The book is written in a dialogical style, where at times, due to their different backgrounds and experiences, Bill and Warren emphasise different aspects of a topic being discussed. They never fundamentally disagree but, coming from differing backgrounds, have different approaches and different ways of talking about things meant to help the reader zero in on the matters under discussion. The book also at times draws on the past writing of both authors while also offering material that has never been made public before.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

First, here is a word from Warren (written in his own pen):

Bill and I go back to 1996, where we met in an online discussion of what has come to be known as MMT.

We differ in at least one distinct respect – Bill writes a lot more than I do, publishing thousands of extended blogs, and numerous and voluminous books. For me, it’s only been short posts on an online bulletin board, a blog with brief entries and question and answer exchanges, and one very short book in 2010.

Over the years I have also published a few academic papers, mainly with co-authors who did most of the writing, while I mostly edited. This book is no different. It was Bill’s idea, and he did most of the writing in his Australian accent, with me editing his drafts with my American accent, and doing very little writing of my own.

It was my suggestion to feature some of the parts I did write by identifying them as ‘From Warren’ and with the text set off from the majority of the text that Bill wrote, and I edited. My thoughts were that this format would give the reader a further insight as to how we’ve worked together on this excellent adventure!

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Well, that can’t be an introduction, can it? So, what is this book about? Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure, embarks on a journey through the fundamentals, implications, and real-world applications of MMT, exploring how it reshapes our understanding of money, government spending, and economic policy. First, let’s talk about the path this quite unique adventure has taken and how we relate it in the book. It is hard to appreciate the whole picture without first coming to terms with how it began.

In Chapter 2 Two Paths, the different paths that Bill and Warren took prior to encountering each other in early 1996 are outlined. Here we have Bill, a young academic from a working-class background who grew up in a Post World War 2 state housing estate in very modest circumstances indeed, making his way up the academic ranks and burying his head in books, data, statistics, and logic. His educational path was smoothed by family assistance provided by the state, and his father, a minimum wage worker, benefitted from the fact that the government believed its responsibility was to sustain full employment. As a teenager he read a lot of literature from famous left-wing writers and melded the theory into a framework for understanding the rather harsh neighbourhood environment he grew up in. Bill was always meant for the academy and while he envied those who could build things or create engineering marvels, he preferred to pursue a path of ideas and books.

All of which defined the research agenda he pursued as a student at university, which he subsequently took into his academic career. In 1978, while still a student at the University of Melbourne, he was musing during one lecture and came up with an idea whereby the Australian government could deal with the high inflation at the time without the need to render workers jobless. At that time, unemployment had started to increase sharply as government used its fiscal policy to cut spending. Bill’s moral template was affronted by the way government were deliberately destroying the prosperity of the lowest wage workers in a mission to control the high inflation. His musing came up with the idea of a buffer stock employment scheme, whereby the government could offer jobs to any workers that were rendered jobless because of the policy attack on the inflationary spiral. By paying a fixed wage the plan would provide a path to price stability. The whole idea took less than one hour to devise but would prove to define, some years later, the career path that Bill took.

Significantly, in that hour of lateral thinking, Bill came to understand that the government could condition the price level in the economy by dint of the price it paid for labour. That idea becomes central to what we now call MMT.

By way of contrast, Warren grew up in, by American standards, very modest middle-class circumstances, then, as he notes, ‘muddled’ through his formal education years as a dreamer, as a sort of off-beat logician. He didn’t have academic aspirations and as soon as he could he began his journey through the hurly burly of the financial markets starting in a small savings bank, moving to the trading desk of Banker’s Trust, a leading primary dealer in US Treasury securities, and then into his own cutting-edge investment and funds management companies. The experience he gained on the ground, dealing with the major macroeconomic institutions such as central banks, national treasuries, and private financial companies contributed to his understandings of capital markets and monetary systems in general. He recognised from firsthand experience that the mainstream narratives about government financial constraints and the purpose of taxes and government debt issuance were at odds with the operational realities of the monetary system. And worse, everyone he met who was directly engaged in monetary operations of the Federal Reserve Bank agreed with him yet did nothing about it.

In response to the absurdity of the 1992 Presidential bid by Ross Perot, where the candidate made ‘balancing the budget’ a centrepiece of his campaign, Warren had had enough and penned his 1993 Soft Currency Economics paper, a tiny paper, with massive implications. He laid out a coherent account of the monetary operations that drive fiat currencies, and, in doing so, demonstrated that the mainstream economic theories relating to government finances and central banking were incorrect. Significantly, as almost an aside he laid out a plan for an Employer of Last Resort (ELR) program, where the government would make an unconditional job offer at a fixed wage to anyone who wanted to work and could not find the opportunity elsewhere. He showed that such a program would demonstrate that the government ultimately through the price it pays for labour, conditions the overall price level.

And from quite different backgrounds and pathways, Bill’s buffer stock employment plan and Warren’s ELR idea – which has become the Job Guarantee in MMT – provided the link – the promotion of full employment policies – which would bring them together in 1996 from either side of the world and begin the MMT adventure.

In Chapter 3 The Paths Meet, the book documents how their separate paths came together via an early Internet E-mail discussion list. The documents provided from the archives of that List, which terminated more than two decades ago, provide an interesting sociology of how the rather ‘outside’ ideas of Bill the young academic, and Warren, the accomplished financial markets insider, were received by the mainstream progressive economists that frequented the discussion list. Most importantly though, Bill’s ideas piqued the interest of Warren who was searching for academic help to advance his own thinking.

At that point, Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure was about to begin, with no idea where it would take them. At the time, the world of economics was dominated by Monetarist thought. Mainstream economists largely focused on market equilibrium, fiscal austerity, and the overarching belief in the self-correcting nature of free markets. On the heterodox side, which was Bill’s milieu, the progressive economists had largely succumbed to the mainstream ideas about fiscal deficits, insolvency threats, currency collapses and the like. From Warren’s perspective, it was because they didn’t understand monetary operations. Bill considered that convergence to be an act of surrender by the progressive side, especially when the main policy contest was always fought at the macroeconomic level. Both were correct. And both soon came to find out that understanding monetary operations, which was self-evident for them, was peculiarly difficult for those progressives to come to terms with.

Amidst this intellectual landscape, a new approach was taking shape. The meme ‘MMT’ was coined on Bill’s blog, and it became MMT that challenged established paradigms and offered fresh insights into how modern economies operate with new global MMT ‘activists’ adding their support within the MMT camp. An improbably grassroots movement had caught fire, soon to topple core mainstream economic models and move to the forefront.

In Chapter 4 MMT 101, the book develops and explains the basic principles that centre on the MMT Money Story. A few years ago, Warren wrote what he called the MMT White Paper, redolent of the great Post World War 2 statements of mission that most governments published to provide their citizens with the planned path to prosperity after the blight of the Great Depression and the Second World War. Warren’s White Paper was a rather terse affair and with some added verbosity from Bill, it becomes Chapter 4, which provides the framework for comprehending the basic departure points of MMT from the mainstream. Once an understanding of the fundamentals is acquired there is no going back. Almost every statement a mainstream macroeconomist makes from that point onward will appear to be comical and threatening to the well-being of ordinary folk. People tell Bill and Warren that when they encounter their ideas, they have this ‘light bulb’ moment, which in some cases, radicalises them into activism. Chapter 4 also provides a simple arithmetic game that readers can play with their kids or at dinner parties, especially if you have economists coming over for dinner.

In Chapter 5 The Job Guarantee – Historical Context, the book considers what was happening in the years when Bill and Warren came to their realisations before even meeting in 1996. The book documents the paradigm shift in macroeconomics in the early 1970s following the disruption caused by the unprecedented OPEC oil price hikes in October 1973. The dominant Keynesian macroeconomics failed to provide a meaningful policy response to the rapidly accelerating inflation that the oil dependent nations experienced, and in that policy lacunae, Milton Friedman’s Monetarists rode into town and performed a rather rapid takeover of the Academy and then sent the cadres out into the central banks and the broader policy bureaucracies. They supercharged the Keynesian ideas about government financial constraints that had been developed during the fixed exchange rate Bretton Woods era that began at the end of the Second World War.

Significantly, around the same time, the world abandoned the fixed exchange rate system, and the era of fiat currencies began, which meant that the legacy theories and policy understandings that were considered relevant during the Bretton Woods era were no longer applicable. That reality was ignored by the Monetarists and their renewed hype about government deficits being dangerous and all the associated dogma and lies, flooded the media, the universities, and dinner tables. The economists demanded that governments abandon trying to keep unemployment low, and instead refocus their efforts on fighting inflation. A very ugly acronym entered the daily lexicon – the NAIRU (Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment) – which has dominated macroeconomic discussions ever since. In the mainstream paradigm, the NAIRU is a unique, unobserved unemployment rate that is associated with stable inflation, and it is claimed that if the government tries to push the actual unemployment rate below the NAIRU, then inflation will accelerate. The theoretical concept is impossible to measure accurately. But that idea, the worst of the worst, then allowed governments to justify abandoning their commitment to full employment, and, instead, start deliberately using higher unemployment as a tool to discipline inflation. The consequences of that shift in thinking among economists have been devastating for the well-being of millions of people around the world. It was this environment that led to Bill trying to conceive of ways to refute what he considered to be the litany of mainstream lies surrounding the amorphous NAIRU concept and develop his buffer stock employment approach.

In Chapter 6 Job Guarantee Mechanics and Issues, the details of the Job Guarantee are outlined in some detail including refutations of the many misconceptions that have arisen over time as people encounter the concept.

In Chapter 7 A Letter to the Minister, a case study is introduced tracing what happened when Bill persuaded local government organisations to petition the Australian Employment Minister to introduce a modified version of the Job Guarantee. The response letter from the Minister, rejecting the entreaty, is illustrative of all the fictional arguments and smokescreens that are erected by the mainstream to kill off any serious challenges to the status quo where the government uses the unemployed as fodder to fight inflation. The hollowness of their defence of the indefensible is stark. The Chapter also demonstrates the dialogical approach where Bill and Warren present rather different perspectives on the meaning of a Job Guarantee job.

In the short Chapter 8 The Full Employment Fiscal Deficit Condition, the book provides readers with an explicit fiscal rule that is compatible with the attainment of full employment and reflects the application of the MMT principles outlined in the earlier chapters. The so-called Full Employment Fiscal Deficit Condition not only defines the appropriate fiscal settings that are required to fulfill the government’s responsibility to ensure there are jobs available for all workers who desire to participate in employment, but it also puts to rest, once and for all, the lurid and fictional claims from critics that MMT economists considers ‘deficits don’t matter’. In MMT, the state of the fiscal balance is a crucial indicator of how well the government is doing in advancing the well-being of the citizens. Moreover, the chapter demonstrates that in some situations that responsibility can be achieved with a fiscal surplus. Sometimes, but usually not.

Chapter 9 Central Banks and all that, takes the reader into the world of central banking and how all that works. Various mainstream fictions about deficits causing interest rates to rise, about MMT being equivalent to a call for the government to just ‘print money’, about the impossibility of so-called central bank independence, and more are teased out. There is a plethora of analysis of the monetary operations of the banking sector, the way in which loans create deposits, and whether the central bank can become insolvent or not. So, if you are contemplating a career in banking, this chapter is for you! In Chapter 10 Inflation and Monetary Policy – Central banks going rogue, the narrative turns to the current inflationary period and details how central bankers, obsessed with what Bill and Warren call the NAIRU-ideology, have gone rogue in their quest for policy supremacy through their interest rate hikes, when it was quite clear that the causes of the inflationary pressures were not sensitive to interest rate changes anyway.

Chapter 11 MMT and International Trade takes the reader into the world of international trade and finance and clearly outlines the unique MMT position that runs counter to the way in which the mainstream and most progressive economists think about these things. There have been so many myths propagated about this sphere of economic activity that have constrained government pursuit of what Bill and Warren call ‘public purpose’. Even progressive economists are wedded to the idea that MMT fails to consider the so-called Balance of Payments Growth Constraint (BPGC), which they claim means that fiscal policy must be subservient to the export potential of the nation. In presentations over the last several decades, Bill and Warren have encountered resistance based on the belief that the currency will collapse if government deficits violate the external constraint. It is surprising to Bill and Warren that progressive thinkers have so constrained their options by adhering in a concept that is so easy to refute.

Chapter 12, the MMT Barbarians Enter the Gates of Canberra details how Bill and Warren engaged with an Australian government debt management review in 2002. The Australian government had been running increasingly large fiscal surpluses since it was elected in 1996 and by the turn of the century the government bond markets were becoming very ‘thin’, meaning there wasn’t much risk-free government debt in circulation for the gamblers in the financial markets to use in their speculative profit pursuits. The Government came under extreme pressure to ensure that there was more government debt in the markets. Who do you imagine was pressuring the government in this way? It was the big investment banks and hedge fund operators who were missing their dose of corporate welfare. These characters want access to the riskfree debt as a benchmark asset to flee to in times of uncertainty and to use to price other riskier products that they were wanted to sell in the markets. Up to that point, the Government had constantly been telling the people that by reducing the government debt levels they were clearing the way for future generations to have lower tax levels and were killing off any risk that they would run out of money as a result of some bond market strike. The mantra of ‘too much government debt’ was continually being rammed down the throats of the people. But then, suddenly, Australians were told there was a new problem – there was too little government debt. The subsequent official inquiry concluded that even though the government was running surpluses, it would still issue billions of dollars of debt each period to satisfy the gambling requirements of the financial markets. Bill and Warren made it clear in their submission that this exposed the cant of the mainstream narratives about government financial constraints. They made it clear once and for all that the government debt was serving the interests of the speculators rather than being necessary to finance government spending. The MMT Barbarians were alone in that view and the media, and the people were none the wiser as to what was really going on.

And finally, one of Bill’s pet topics – Japan. Chapter 13 Japan – the MMT Laboratory, provides an exhaustive understanding of what gives in 日本 – the land of the rising sun, which Bill considers to be his MMT laboratory. Warren, too, was no stranger to Japan. In 1996 he orchestrated the largest ever delivery of Japan Government Bonds (JGB’S) to the Tokyo international financial futures exchange (TIFFE) to a cabal of dealers, intent on bankrupting him. Warren prevailed, and the dealers cowed under the wrath of the Bank of Japan for conspiring to undermine and risk the solvency of the entire JGB clearing system. Warren subsequently named his dog Tiffe and got a JBU6 license plate for his car.

The Chapter outlines how the conduct of fiscal and monetary policy in Japan since the major property market collapse in the early 1990s has sent mainstream economists both from outside and within Japan into conniptions. The severity of the asset bubble burst forced the Japanese government to deploy policy settings that could be considered relatively extreme – significantly higher fiscal deficits, zero interest rates, large-scale purchases by the Bank of Japan of government debt – all the settings that the mainstream considered would lead to catastrophic failure, hyperinflation, government insolvency, and chaos. One by one, the mainstream economists lined up in the 1990s and beyond with their dire predictions. Each one went home unhappy. Japan has demonstrated unwittingly that the major elements of mainstream macroeconomic theory and practice are wrong and are inapplicable to a modern fiat monetary system. Bill and Warren point out the peculiar irony of all this. Because while the outcomes from those rather atypical policy settings have exposed the fictions of mainstream theory and practice, the policy makers in Japan introduced those atypical policy settings believing they would have mainstream outcomes. It is amusing to say the least.

You are about to embark on a journey through the fundamentals, implications, and real-world applications of understanding the MMT framework for analysis, exploring how it reshapes our understanding of money, government spending, and economic policy. The journey documents the birth of a new paradigm that has emerged from a deep rethinking of the role of money in the economy. Unlike traditional theories that treat money as a finite resource akin to gold or silver, MMT views money as a social construct–created and regulated by sovereign governments. This shift in perspective has profound implications for how we understand fiscal policy, inflation, and economic stability.

Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure documents the journey they took and intersperses personal accounts with the hard-core economics. As you delve deeper into the chapters of this book, you will explore how MMT provides a robust framework for understanding the complexities of modern economies. You will examine case studies, historical examples, and theoretical insights that illustrate the practical applications of MMT principles. From addressing unemployment and inflation to rethinking the role of central banks and fiscal policy, Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure aims to equip readers with a comprehensive understanding of this transformative economic paradigm as told by the originators.

Join us as we embark on this intellectual journey, challenging old assumptions and discovering new possibilities for achieving economic prosperity and social well-being in the 21st century. The adventure of MMT is not just an academic exercise but a quest for a more just and equitable world.

And lastly, Warren’s first word above obviously wasn’t all he wanted to say:

From my point of view, MMT saved the world during COVID. Less than 10 years before, after the crash of 2008, fiscal responsibility was still all the rage. President Obama and Secretary Clinton flew to China, ‘our bankers’ to make sure they would finance our debt for the new stimulus proposal, which had been cut in half out of solvency fears. Paul Ryan, Speaker of the House, was mouthing off about the US becoming the next Greece, on its knees before the IMF begging for funding. Mainstream economists warned of out-of-control interest rate increases and bond market collapses from the rising public debt.

Contrast that with 2020 and the Congressional approval of $5 trillion of emergency spending. Not a mention of China, Greece, or interest rates. Solvency was no longer an issue. There was only a muted discussion about possible inflation.

What happened? MMT happened! MMT, through no small efforts of all of the MMT team.

While there is much to be done to finish the job of permanently ending involuntary unemployment, I couldn’t be more pleased than to live long enough for Bill and me to see MMT sufficiently emerge just in time to save the world, as nations globally, for the most part, spent as needed to cover the COVID-induced spending gaps, ignoring their previously presumed fiscal constraints. Even the euro area, bastion of fiscal responsibility and the iron-clad, ECB enforced 3 per cent deficit rule, let loose with deficits exceeding 10 per cent of GDP, with that ground having been prepared by Italian MMT activism, that I had been working with since 2013, including visiting professorships at Bergamo and Trento, giving daily presentations including excursions to numerous presentations at universities throughout Italy.

Thanks Bill, it’s been a truly excellent adventure!

So, get on your bikes and join the peloton and let the journey begin!

At Cambridge University, July 4, 2008. Bill’s tie needed straightening while Warren forgot his.

2 TWO PATHS

ADVENTURE NOTES

In this Chapter, we trace the independent paths that Bill and Warren took prior to meeting up in 1996 and beginning their MMT Adventure. Their backgrounds and separate paths as they developed their ideas help us understand how MMT was spawned in the mid-1990s.

WILLIAM MITCHELL

Bill took a very different career path to Warren. He grew up in a Post-World War 2 state housing commission estate in a working-class family. His father was a minimum wage earner, and his mother didn’t work in paid employment during his formative years, such was the sociology of the times that was biased against females participating in the workforce after marriage. He went to a state high school and while achieving high academic results was expelled in his final year because of his constant questioning of authority. At university, he initially studied for an Arts degree but later, after a disruption to his studies, he returned to undertake a commerce degree majoring in economics and politics, with statistics.

There were two striking developments in economics in this period. On the one hand, a major theoretical revolution was becoming entrenched in macroeconomics; while on the other hand, unemployment rates had risen and were persisting at the highest levels known in the Post World War II period.

At the same time the economic performance of the OECD economies was failing badly. In 1972, Australia’s inflation rate was 6.2 per cent, but following the first OPEC oil shock in 1974, aided by some large wage increases, the inflation rate reached 15.4 per cent in 1974, and 17 per cent in 1975. By the end of the 1970s, despite a period of subdued activity and rising unemployment, the inflation rate was still high in relation to Australia’s trading partners at 9.2 per cent.

By the time Bill had reached the honours level in 1978 (fourth year in an Australian undergraduate program), unemployment in Australia had risen from around 2 per cent in 1974 to over 6 per cent by 1978. This was the era of stagflation (coincident high unemployment and inflation). During this time, the economics discipline had abandoned the so-called ‘Keynesian’ full employment thinking and adopted Monetarist ideas which were the precursor of what we now, more generally, refer to as neoliberalism. American economist Alan Blinder (1988: 278) wrote that by ‘about 1980, it was hard to find an American macroeconomist under the age of 40 who professed to be a Keynesian. That was an astonishing turnabout in less than a decade, an intellectual revolution for sure.’ The main feature of the new economic paradigm was that discretionary government policy was ostensibly rejected in favour of a market-dominant approach where the regulative framework was dismantled, government enterprises were privatised, and importantly, unemployment became a policy tool to discipline the inflationary pressures of the time, rather than being considered a policy target to be minimised.

Economists advocated significant cutbacks in net government spending to deal with the inflation realising that it would drive up unemployment. They then justified the rise in unemployment by introducing a new idea – the natural rate of unemployment – which had been articulated by Milton Friedman and others in the late 1960s.

Effectively, this new way of thinking claimed that governments could no longer use fiscal and monetary policy to reduce unemployment and if the unemployment rate was considered to be too high, then the only recourse would be to engage in so-called microeconomic reform, which spawned all the supply-side labour market programs that began in the 1970s (work tests, training instead of job creation, and more).

Bill eschewed this trend in economics from a moral perspective considering access to paid work to be a human right and was interested in working out ways to deal with the inflationary pressures of the day without the need to significantly increase unemployment. In 1978, this mission spawned the idea of a buffer stock of employment (BSE). The BSE model later became the Job Guarantee concept in MMT and is based on the same logic as the ‘Employer of Last Resort’ idea that Warren had independently developed in his 1993 work. We

Figure 2.1 Bill’s Final Fourth Year Transcript from the University of Melbourne, 1978

will see in Chapter 3, that this correspondence of thought provided the basis for the formation of a working relationship between Bill and Warren in early 1996 – the beginning of the Adventure - that produced what we now call MMT.

In 1978, Bill began his fourth year of studies (transferring to the University of Melbourne). As part of those studies, he was required to undertake coursework units and the basis of the BSE policy came to him during a series of lectures in the agricultural economics unit taught by A.G. Lloyd on the Wool Floor Price Scheme which had been introduced by the Australian Government in November 1970.

This was, of course, in the pre-digital age and after many house moves within Australia and between countries, no written material from that year has survived. Bill’s transcript from that year shows his subject enrolments, and, the buffer stock idea must have been well thought off, because as the transcript shows, the examiners in the subject Economics C9 gave him the top marks in that year (Figure 2.1).

The Wool Price scheme was relatively simple. The federal government established a floor price for wool after hearing submissions from the Wool Council of Australia and the Australian Wool Corporation (AWC). The government then guaranteed that the price would not fall below that level. There was a lot of lobbying to get the floor price as high above the implied market price as possible. The price was maintained by the AWC purchasing and selling stocks of wool in the auction markets. The financing of the purchases came from a Market Support Fund (MSF) accumulated by a small contribution from growers based on the value of its clip. Fund shortages were made up with government-guaranteed loans. The major controversy for economists was the ‘tinkering with the price mechanism’ (Throsby, 1972: 162). There was an issue as to whether it was price stabilisation or price maintenance. This was not unimportant in a time when prices were in sectoral decline and a minimum guaranteed floor price implied ever-increasing AWC stocks. Other problems included the problems of substitutability from synthetic fibres and the maintenance of production levels, which would by themselves continue to depress prices. The debate over the scheme (adequately summarised by Parish, 1964; and Lloyd, 1965) focused on the price intervention.

Bill applied reverse logic to utilise the concept without encountering the problems of price tinkering. In effect, the Wool Floor Price Scheme generated ‘full employment’ for wool production. Clearly, there was an issue in the wool situation of what constituted a reasonable level of output in a time of declining demand. The argument is not relevant when applied to available labour. Bill considered full employment to be the state where there was no involuntary unemployment and that was determined by the supply of labour at the current money wage rates. The corresponding demand for labour at the existing money wage rates merely determined the magnitude of involuntary unemployment.

The reverse logic implied that if there was a price guarantee below the prevailing market price and a buffer stock of working hours constructed to absorb the excess supply at the current market price, then the government could generate full employment without encountering the problems of price tinkering. That idea was the seed of the BSE model.

Under the BSE scheme, the government continuously absorbs workers displaced from the private sector. The buffer stock employees would be paid the minimum wage, which defines a wage floor for the economy. Government employment and spending automatically increases (decreases) as jobs are lost (gained) in the private sector. The approach generates full employment and price stability. The BSE wage provides a floor that prevents serious deflation from occurring and defines the private sector wage structure. However, if the private labour market is tight, the non-buffer stock wage will rise relative to the BSE wage and the buffer stock pool drains. The smaller this pool, the less influence the BSE wage has on wage patterning. Unless the government stifles demand, the economy will then enter an inflationary episode, depending on the behaviour of labour and capital in the bargaining environment. In the face of wage-price pressures, the BSE approach maintains inflation by choking aggregate demand and inducing slack in the non-buffer stock sector. The suppression of non-buffer sector output asserts the numeraire price -- the BSE wage. This leads to the definition of a new concept, the Non-Accelerating Inflation Buffer Employment Ratio (NAIBER), which, in the buffer stock economy, replaces the NAIRU/MRU as an inflation control mechanism (Mitchell, 1987a). The Buffer Employment Ratio (BER) is the ratio of buffer stock employment to total employment. As the BER rises, due to an increase in interest rates and/or a fiscal tightening, resources are transferred from the inflating non-buffer stock sector into the buffer stock sector at a price set by the government; this price provides the inflation discipline. The disciplinary role of the NAIRU, which forces the inflation adjustment onto the unemployed, is replaced by the compositional shift in sectoral employment, with the major costs of unemployment being avoided. That is a major advantage of the BSE approach.

The ramifications of that idea were significant.

• The government could achieve full employment without inflation – which meant that the whole Phillips curve trade-off debate (whether the curve was sloping or vertical) between the Keynesians and Monetarists was moot. In effect, the Phillips curve could be rendered horizontal, meaning there was no inflation pressures emerging if the government absorbed the excess supply of labour into the buffer stock.

• Importantly, the model established that the price level ultimately could be disciplined by the price the government paid for labour, which is a fundamental principle in what we now consider to be MMT.

As part of the development of the BSE concept, Mitchell read the work of Benjamin Graham (1937) who discussed the idea of stabilising prices and standards of living by surplus storage. Graham documented the ways in which the government might deal with surplus production in the economy. Graham (1937: 18) said ‘The State may deal with actual or threatened surplus in one of four ways: (a) by preventing it; (b) by destroying it; (c) by ‘dumping’ it; or (d) by conserving it.’ In the context of an excess supply of labour during the stagflation era, governments had adopted the ‘dumping’ strategy. Bill considered it made much better sense to use the conservation approach when it comes to labour. Graham (1937: 34) notes that:

The first conclusion is that wherever surplus has been conserved primarily for future use the plan has been sensible and successful, unless marred by glaring errors of administration. The second conclusion is that when the surplus has been acquired and held primarily for future sale the plan has been vulnerable to adverse developments …

The distinction was important to developing the BSE model. The Wool Floor Price Scheme was an example of storage for future sale and was not motivated to help the consumer of wool but the producer. The BSE policy is an example of storage for use where the ‘reserve is established to meet a future need which experience has taught us is likely to develop’ (Graham, 1937: 35). Graham also analysed and proposed a solution to the problem of interfering with the relative price structure when the government built up the surplus. In the context of the BSE policy, this meant setting a buffer stock wage below the private market wage structure, unless strategic policy in addition to the meagre elimination of the surplus was being pursued. For example, the government may wish to combine the BSE policy with an industry policy designed to raise productivity. In that sense, it may buy surplus labour at a wage above the current private market minimum.

While these considerations were teased out in Bill’s later research, the basic BSE model constructed in 1978 proposed creating a wage floor below the private wage structure.

Graham (1937: 42) considered that the surplus should ‘not be pressed for sale until an effective demand develops for it.’ In the context of the BSE policy, this translated into the provision of a government job for all labour, which was surplus to private demand until such time as private demand increases.

On the financing issue, Graham was particularly insightful. Once again, the distinction between conservation for future use (the BSE) and conservation for future sale (Wool Floor Price Scheme) is important.

Graham (1937: 43) said that the latter:

suffered from the fundamental weakness that they depended for their success upon advancing market prices … A price-maintenance venture is inherently unsound must in all probability … result in serious financial loss … But a rational plan for conserving surplus … should not involve the State in financial difficulties. The state can always afford to finance what its citizens can soundly produce. (emphasis in original)

For Bill, this insight appeared to solve the ‘How to pay for it’ challenge. The application to the BSE model was that the government could always purchase the services of idle labour that wanted to work and earn the dollars the government spent. At the time, the later refinement of the fiscal issues and bond markets that Warren brought to the table in the 1990s were not developed in the BSE model.

Graham (1937: 90) also foresaw the mainstream NAIRU approach, which in effect is an unemployment buffer stock approach to inflation control, when he said that ‘unemployment operates as a crude mechanism for correcting the unbalance of demand and supply.’ His ‘Reservoir system’ proposes that the State buys and stores ‘composite units’ of basic raw materials when they are in surplus at a unit price (the money value of the unit being the quantity of combined commodities equivalent to a dollar) fixed at some appropriate level. The composite units are paid for by new currency and are convertible. The surplus production is thus stored without destroying incentives in the markets. The system generates price stability because the price level for the composite price level is fixed in the same way that gold was fixed under the gold standard.

Further, Bill realised that the BSE policy did not encounter the problems associated with the storage of raw materials. It can be seen as ‘storing private labour services’ and putting them to use in public projects. In this way, the production of private commodities reflects the level of overall spending, and the unwanted labour resources are re-allocated to areas that the private sector does not service.

After completing a Masters degree at Monash University in 1982, Bill then ventured to Canada to undertake a PhD at Queens University in Kingston, on a Commonwealth Scholarship. He lasted in Canada three weeks and was deported back to Australia because the Canadian Embassy in Sydney had given him the wrong visa. The Canadian Immigration authorities let him in on a temporary visa while they sorted out the implications. Soon they told him he would have to cross the Canadian border and get the right visa and then he could return to start his studies. The US authorities were approached in Buffalo – which seemed logical given its proximity to Kingston. They said he could enter the US but only if the Canadians guaranteed to let him back in. Apparently, no guarantees could be given and so he was told it was Sydney or bust. Bill sent the Canadian Minister of Education a note saying that if he had to go all the way back to Sydney then he would not be coming back. And so, it turned out that way.

Six months later, he won another Commonwealth Fellowship and started doctoral work under Professor Michael Artis at Manchester University in the early-1980s. During the 1970s, the Department of Economics had been hosting the famous Manchester University Social Science Research Council-financed Inflation Workshop project, run by the likes of David Laidler and Michael Parkin. While Laidler and Parkin had packed their bags and headed to the University of Western Ontario in 1975, Manchester was still a hot bed of Monetarism and Bill thought no better place to be for someone who was so opposed to this new paradigm in macroeconomics. Michael Artis had an Australian connection as his first academic job was in Adelaide and he had some affinity for the dry Australian humour and made Bill feel welcome in this academically hostile environment. The aim of his research program was to contest the dominance of the mainstream natural rate of unemployment theory, which had justified the dramatic rise in unemployment in the high inflation era following the OPEC oil price increases, that began in October 1973. Professor Artis had published widely on issues relating to the so-called Phillips Curve (the relationship between unemployment and inflation) and Bill began to work on the question of the stability of the Phillips curve and on the issue that had not yet emerged in the professional literature - path dependence or hysteresis. This latter concept conjectured that the government could use its fiscal capacity to drive the unemployment rate down without causing accelerating inflation and was consistent with his earlier idea of a buffer stock employment policy program.

Bill’s later work extended the BSE concept to the small, open economy and considered the financial implications of the BSE model for such an economy. The important point here is that the subsequent, largely U.S.-based MMT work that was spawned by the initial work of Warren and Bill, assumes a large, closed economy. The dynamics of the two types of economies are rather different and so the application to the small, open economy allowed for the generalisation of MMT and allowed Bill and Warren to head off criticism that the ideas only applied to the U.S., whose currency is also the dominant trading currency.

By then Bill had set up the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (a.k.a. CofFEE) at the University of Newcastle where he went to work in 1990 after working for a few years at The Flinders University of South Australia in Adelaide upon his return from the UK. He also spent a brief time working for the Federal Department of Employment and Industrial Relations as a research officer in between returning from the UK and moving to Adelaide. He learned a lot about how policy is made and managed while working in Canberra. CofFEE became the centre of MMT work in Australia and Bill hosted annual conferences that facilitated visits from the US MMT colleagues. They were very heady times.

WARREN MOSLER

Warren initially studied engineering at the University of Connecticut, reflecting what became a lifelong interest in engineering. He has designed and built a wide range of technologically ground-breaking vehicles, including record-breaking race cars and working ferries (Armstrong, forthcoming). However, during his undergraduate years, he changed course to economics, and graduated in 1971. During his studies, Warren had limited exposure to economics, needing only three courses for his degree, and only reading one book, The ‘Affluent Society’ by John Kenneth Galbraith, which resonated with his own thinking and approach. Interestingly, the title of Warren’s seminal work of 2010, ‘The Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy’ pays homage to Galbraith’s final work of 2004, ‘The Economics of Innocent Fraud: Truth for Our Time.’

Warren’s first serious job was at the Savings Bank of Manchester, Connecticut, and it was during his time there that he began building his understanding of the financial system. He subsequently worked at Bache and Co. in Hartford, Connecticut, where he obtained his licence to sell securities. In 1976 Warren moved to New York to work at Bankers Trust, a primary dealer on Wall Street, as Assistant Vice President, specialising in mortgage-backed securities and derivatives. It was during his time on the money desk at Bankers Trust, that Warren gained a working knowledge monetary operations, which included the understanding that the funds to buy Treasury securities came from the Treasury’s deficit spending of that same amount, and the process by which the Fed, as single supplier of reserve balances, controlled the fed funds rate as it continuously ‘offsets operating factors’ as it was called.

Warren’s later conclusions logically followed, including: