Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

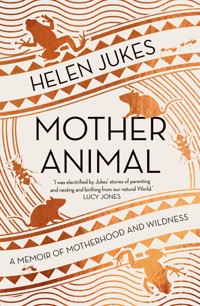

An electrifying new vision of motherhood from the author of A Honeybee Heart Has Five Openings - 'ASTONISHING' (Sunday Times) When Helen Jukes falls pregnant, she does what anyone else would do. She searches for information to help make sense of the changes underway inside her. But as the months pass and her body becomes increasingly strange, the pregnancy guides seem insufficient; even the advice of her friends feels oppressive. So she widens her frame of reference, looking beyond humans to ask what motherhood looks like in other species. Here she begins a process of wilder enquiry, in which stories of spiders, polar bears, bonobos and burying beetles (among others) begin to unsettle and expand her notion of what mothering is; what it could be. A passionate, visceral and intimate account of a body changed, Mother Animal combines personal memoir with fresh insights from evolutionary biology, zoology and toxicology to ask the big questions that lie at the heart of what it means to be alive – and a mother – today. __ 'Magnificent' Lucy Jones, author of Matrescence 'Joyful and expansive'Guardian 'Blows societal ideas about parenthood wide open.' Marchelle Farrell, author of Uprooting 'Extraordinary... Read it to feel a slow detonation of mind-blowing understanding.' Daisy Johnson, author of Sisters 'Honest and unflinching'Stylist

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 284

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Unlike anything I’ve ever read. A tender and bewildered account of motherhood, and a powerful reflection on what it means to be alive in the Anthropocene. There is so much beauty here – and so much uncertainty – as well as an extraordinary capacity to inhabit both conditions at once. Jukes’ voice is cracked open to the world, but to be cracked open is also to be joined to others, not only in exposure and risk, but through care and solidarity. The achievement of this book is to widen those circles of care – and to situate human experiences of mothering within the vast unfolding story of our animal neighbours and kin.’

Michael Malay, author of Late Light

‘Mother Animal wrests motherhood from the clutches of the patriarchy and gently places it back into the hands of birthing bodies, human and non-human. A dream blend of exquisite personal memoir and compelling environmental writing, I gobbled it in one sitting.’

Sally Huband, author of Sea Bean

‘Jukes doesn’t mess around. She has a genius for getting straight to the heart of the matter. And when the matter is – as it is in Mother Animal – the whole business of how to live properly as a human, you simply must hear what she has to say. It will change you.’

Charles Foster, author of Cry of the Wild

‘A deeply thoughtful interrogation of motherhood and the way it ties us to our natural (and not-so-natural) environment.’

Leah Hazard, author of Womb

‘This beautiful exploration of pregnancy and motherhood brilliantly and powerfully explores and expands our understanding of the mother-nature / nature-mother space. By breaking down borders between human and animal “mothering”, this wonderful, profoundly personal journey in and out of self leaves us feeling at once wilder and, somehow, more human.’

Rob Cowen, author of The North Road

‘A beautifully written exploration of pregnancy, birth, and parenting. With an emotional precision, Jukes stitches human and animal lives into a vivid tapestry that is as moving as it is illuminating. I found solace in connecting to my animal self. A book to devour.’

Joanna Wolfarth, author of Milk

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

I The Enclosure

II Birth

III Animal Formulas

IV Forever Milk

V Nests

VI Communities of Care

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Memory is by nature friable, and during periods of extreme sleep deprivation profoundly so. This book is an attempt to mark a path through that uncertain territory while remaining true to the emotional tenor and my own recollections of that time.

For reasons of anonymity I started out by changing the names of some of those who appear in these pages, but as an approach this soon felt inconsistent, so in the end all names have been either changed or omitted.

A note on terminology: I have tried to distinguish in the text between the ‘animal mothers’ dreamed up by Western science, and ‘mothering creatures’ – a term that encompasses a whole array of parenting experiences from the natural world, some of which are still in the process of becoming known to researchers. Though I describe my own journey as a woman who carried my child through pregnancy, and while I am particularly curious about how the experience of female parents in Western, patriarchal society may be circumscribed by ideas of Nature and naturalness, I hope that the emergent truth of this book is one of diversity and change. Not all mothering creatures are female; not all are biological parents; many act as part of wider communities, in complex relationships with other individuals and species.

This being a personal and sometimes circuitous story of surprise and discovery, it does not and could not offer an exhaustive study of parenthood in the animal kingdom – that work is best done by others. New research is emerging all the time, and with luck someone else will soon write another book about animal parenting, and then another. For now, here is what I learned, and if there are grounds for alarm in what is contained here, I hope there is also much to inspire wonder.

I

THE ENCLOSURE

The month I found out I was pregnant was a record-breaking one – the planet’s hottest since measurements had begun. It was July, and we were caught in a blistering heatwave; a pocket of high air pressure stretching from western Russia all the way to the Atlantic. Everywhere there were stories of desiccation and sudden deluge. In Berlin, police were using water cannons usually trained on rioters to cool the city’s trees; in France, they were cautioning the public against diving in unsanctioned pools. In Greece, helicopters had been brought in to stem wildfires that had whipped through sun-baked pine forests and over roads and into houses, sending inhabitants running for the sea from which the firefighters flew. On a farm near us, thousands of chickens had just sweltered to death when barn ventilation systems failed – an uneasy foreshadowing of the nearly 900 people in the UK who would die as a result of the heat that summer, most of them not out in parks or on beaches but in their own homes, which had overheated.

Our house, a small worker’s cottage built nearly four hundred years ago with thick limestone from the surrounding hills, held on to the cool – even in midsummer it was a place of shady corners, of surprise relief, the sash windows pulled down at the top and up at the bottom to catch any breeze that passed.

Outside, the earth hardened and the grass bleached. I went for walks in the early mornings and evenings, and if I passed others on the footpaths, we spoke of little but the weather – our tones initially elated and later, increasingly, alarmed. Inside, there were surprise infestations: ants teeming from the skirting boards, a wasp’s nest blooming over the back door. The insects were armoured and manifold, aggressive in their work of procreation – I, on the other hand, couldn’t seem to do a thing. I felt clammy and then swollen, as though I were retaining moisture somewhere, which I suppose I was – a thin layer of cells in my uterus having formed a filmy sack in which water and electrolytes and a small cluster of cells now floated and multiplied.

I thought at first it was the weather making me sick. I wasn’t used to the temperatures, the long hot days. I’d missed a period. But perhaps people missed periods in the heat? Still, I drove into town for a pregnancy test, returning pinked and nauseous, pupils shrunk to pinpricks, blinking. Squatting over the toilet, I fumbled with the plastic pen, blindly waving the flimsy thing as urine mixed with the paper strip and with the damp sweat on my palms.

A blue line. The colour of water, oceans, incontrovertible facts. The radio was on in the kitchen. There was talk of thunderstorms.

I’ve read that some escapologists and deepwater divers slow their heart rates and manage their fear by ‘remembering’ being in the womb – a time when mouth, nose, ears and lungs are filled with liquid, and we possess no fear of being submerged in water, or of being without it.

That night, the night of the pregnancy test, I remember the house looked different. I was suddenly aware of its imperfections: the cracks in the plaster, the loose wires hanging from the ceiling and the damp patches along the walls. The place seemed shaky somehow – full of waiting hazards and jobs that, since moving in the previous winter, had gone unfinished.

We sat at the table, making a list of tasks to be completed over the coming months. —We’ll have to fix the floorboards, I was saying —and we should repair the windows, and get the boiler serviced, we might have to replace it, don’t you think?

My boyfriend glanced in the direction of the window. Outside, the sky was cooling, the blue deepening, the heat lifting slowly from the hills. —Are you listening? I said. —Sure, he said. —Sure, the boiler service. Have you noticed the ants are back?

And there they were, visible as a patch of brittle-looking movement beside the skirting board. He frowned. —I’ll look it up, he said. —I’ll look up what to do.

And with that, we returned to our phones – he to his pest control measures, and me to the news. The Guardian had done a photo feature on how animals were coping with the heat. There were pictures of zookeepers rubbing sun lotion onto the backs of tapirs and feeding ice lollies to polar bears; of farmers rescuing fish from lakes that were fast disappearing. I suppose this was intended to offer some comfort: look here, at Nature’s creatures! Look at these creatures surviving! And at these enterprising humans, still capable of rescue despite everything. I scrolled, clicked, scrolled again, and came across a video someone had posted of a bonobo mother in a zoo not far from us, sheltering her infant from the midday sun.

I remember feeling very keen, as I watched this film, to deduce the breadth and type of her enclosure. A climbing frame, a patch of grass. Fences, walls. The mother cradled the infant as she roved from one patch of cramped and crowded shade to another. But she looked nervous, I thought. She looked visibly stressed. She couldn’t escape, was the thing. She couldn’t escape the heat.

What the internet suggested we do about the ants:

Poison them

Pour boiling water over them

Hoover them up

What happened when I hoovered them: more came. And by September the inside of the hoover contained a layer of furry little carcasses gently decomposing inside the plastic.

The first trimester, then: sticky, nauseous, a strong aversion to most tastes and smells, a sudden desire to disinfect everything, foggy-headedness, tense hope.

The word nausea comes from the Latin nausea, meaning seasickness, and from the Greek nausia, meaning disgust and – literally – ship-sickness, but in English the word has always held associations beyond oceans. In nausea, it is possible to be both at sea and landlocked; to inhabit a body utterly persuaded that all taste, all touch, all outside stimulation is utterly, incorrigibly detestable. You long for the world to become still, for all movement to stop – knowing as you do that the source of your problem resides not with the world but your own insides, which have conspired to hold you like this: confined, desperate, unable to stop feeling.

Standing shakily in front of the bedroom mirror, I scoured my body for signs of change. Was my left breast not slightly fuller than last week? Was there not a new roundedness, now, to my middle? Was it OK to want this, while fearing for its future?

It seemed unthinkable that I, my body, this taut and nervy frame, might possess the practical wherewithal to gestate and birth another being. Yet if this was truly happening, it appeared to be proceeding in a surprisingly haphazard way. Discernible changes were not limited to those parts of myself where I had assumed gestation took place, but instead proliferated wildly, erupting in sudden and increasingly bizarre ways: tears at bedtime; light-headedness in the shower; new dark hairs springing from around my ankles and upper lip. What was I becoming? During pregnancy, the singer Adele reportedly grew a beard. ‘I call it Larry,’ she told a magazine, as though in coming to motherhood one might birth not just a baby but an alter ego – a second self. (Did Adele discover too that, in the months after childbirth, a mother’s voice deepens by as much as a piano note? That the reverse happens outside of pregnancy and around the time of ovulation, when voice pitch increases, since the hormones behind egg release also have a hand in voice?)

I bought a foetal development chart and hung it up in the kitchen. The chart broke pregnancy down into forty pages and forty weeks; each week, a picture of a different fruit corresponded to the size of the growing foetus.

Six weeks: a pomegranate seed.

Seven weeks: a blueberry.

The delicious horror of skipping ahead – imagining oneself harbouring an aubergine, a watermelon.

By now I’d dipped into pregnancy websites and learned the dos and don’ts by heart. Do rest, eat plenty of fruit and vegetables (but be sure to wash them first), exercise (but nothing too strenuous) and trust your instincts. Don’t eat raw meat, unpasteurised milk or cheese, uncooked eggs or shark or swordfish; don’t drink alcohol; don’t inhale cigarette smoke or some paint fumes; avoid dry-cleaning fluids, cat litter, hair dye and overly hot baths. Also, use your seat belt. Also, don’t be anxious.

So the air I breathed contained petrochemical fumes that increased the risk of miscarriage; the soil on a carrot could contain parasites that could cause foetal brain or liver damage, or miscarriage. And what if on occasion I forgot the rules? What if I misinterpreted them, or misplaced them, or ate a cheese I shouldn’t? Miscarriage!

I was not just a vessel but a membrane – a thinking, feeling boundary between my unborn child and the rest of the world, both at the mercy of whatever threats were at large in my environment and locked in an urgent, impossible struggle to control it. I began peeling mushrooms before eating them. I ordered an organic veg box, roasted a cauliflower for the first time, spent long minutes scanning the ingredients on food packets in the supermarket. Was it still OK to reheat old rice? Was it less OK than before? And all this in service to a different kind of foreignness – a body of cells, now person-shaped, steadily blossoming on my inside.

At twelve weeks the foetus was passionfruit-sized, and I had learned to eat crisps to stem the nausea, and that the development chart I’d hung in the kitchen was full of shit. Foetal size varied, of course it did – so did vegetables and fruit.

At twelve weeks, the roughly passionfruit-sized foetus had developed rounded buds that would eventually become teeth; the basic structure of a skeleton now hardening into bone. Occasionally, unbeknownst to me, it made a jagged little movement – spasmodic expressions of joints, limbs and growing musculature.

I lay on a bed with a plasticky feel as a bearded man in blue hospital scrubs lifted my trouser band up and lowered it, and I watched as beads of light on a screen above my head moved in and out of a human form. A bowed head, a coiled leg. A tiny, too-perfect fist. The man clicked quietly at his computer. But something was wrong – the limbs were frozen, motionless. He hadn’t noticed. How had he not noticed?

—It’s not moving, I said, growing panicky. The sonographer looked up, surprised. —It’s a photostill, he explained gently. —Look. See that? He held a cursor over a thick dark region in the top right corner of the screen. —There.

It looked to me like a void. —What is it? —Your placenta.

I squinted. I wanted him to point again to the legs, the feet, the little alien head. I tried to recall what the placenta was, what it did. He twizzled his probe and prodded and the creature inside me on the screen gave a jerk. I had, I realised, very little understanding of what actually in a physical sense was going on.

When first attaching themselves to the walls of the uterus, placental cells disguise themselves as uterine cells, convincing the body that they are a part of it although in fact they are not a part of it, or not exactly. Exactly, they are something different: a fast-growing and completely novel organ with the sole and finite purpose of gestating another body, another being. The deception is necessary because without it the body would identify the cells as foreign and destroy them.

The placenta connects, then, while keeping separate, supplying the foetus with nutrients and oxygen, removing waste and producing hormones that help regulate interactions with the maternal body. Looking it up, I was diverted – found myself on a page for veterinary science, scrolling through diagrams of placental forms. Diffuse, cotyledonary, zonary, discoid. They were the shapes of croissants, bao buns, deep-sea worms – irregular, ragged, flaccid-looking things, more reminiscent of abstract art than science textbooks, or bodies.

Cow placentas are tufted. Dog and cat placentas form a band like a seatbelt around the amniotic sac; so do elephants’. In some form or other, the placenta has evolved multiple times, along otherwise independent branches, in every vertebrate group except birds – and so I had this curious, just-made organ in common with expectant boa constrictors and water voles; with some sharks and rays and bony fish. All species who at some point in history began retaining embryos inside their bodies and releasing their offspring whole.

Longer gestation times offer greater protection for developing offspring, but they are riskier and more resource-heavy for the mother, who also, literally, gets heavier. Bats fly slower and lower in late pregnancy; the dolphin experiences a 50 per cent increase in swim drag. The foetus of a humpback whale reaches such epic proportions inside her that it comes to function as an acoustic object – a symptom of late pregnancy, as Rebecca Giggs puts it in her book Fathoms, is ‘a shift in the timbre of the mother’s voice’.

While speaking on the phone, I often doodle on the edge of my diary, repeating little circles or squares or misshapen stars, and at a certain point in pregnancy these doodles turned to placental forms.

The human placenta, a discoid shape, averages a thickness of around two and a half centimetres, and by the end of pregnancy may weigh somewhere in the region of 500g. We tend to speak of it as belonging to the mother, but this gives a misleading impression – it is made up of embryonic cells as well as maternal ones. It is, in part, the creation of a person still in the process of being formed. Burying deep into the womb lining, it taps into bodily tissues and the wider arterial system with such forceful invasiveness that one can’t abort a human pregnancy without risk of lethal haemorrhage.

My doodles were shaped like boats, and then like branches – the intricate vessel structure covering the placenta’s foetal side. Sinuous and extensive, dividing again and again, I doodled it into the margins and across the days of the week as I spoke with students about their end-of-year projects; as I chatted with friends about summer plans. I’d told a few of these friends, by now, that I was pregnant. —I’m not sure what to do, I’d told them. —Should I be preparing or something? I don’t know how to make it feel real. Hearing this, they’d been laid-back. —Just do what feels natural, one of them had said, and I’d come away confused, unsure if I felt natural or not.

It was around this time that I found myself returning to the film of the bonobo mother. Protective bonobo mother takes care of newborn amid scorching heat, the caption read, and what struck me now as I watched it again were the multiple narratives this triggered. The racketed temperatures, the scorching heat, and yet the vision front and centre of the devoted mother. What had the person filming seen here – what were they inviting me to see? A glimpse of a world out of kilter, or one of Nature’s resilience, its capacity to carry on regardless? Perhaps both. Yet this put a lot of pressure on the figure of the mother, who alone appeared responsible for maintaining an image of naturalness, for ‘taking care’, even as the air around her boiled.

The bonobo moved, restlessly, under her block print caption. I found that I was interested in her, in what she was like. I imagined her imbued with maternal instinct, with innate knowledge about what to do. I understood that I would soon be imbued with this too, though I had little sense of the means or timing of its arrival. I’d read about waters breaking. If this didn’t happen naturally (that word again), I had been told that a doctor would end up doing it for me; doing it to me. I pictured a metal implement (a fondue fork, a fishing hook) inserted rudely up my vagina; an ensuing pop, like a water-filled balloon, like the water bombs we made as kids, whereafter I would be hit – smack! – by the, my, instinct. (And what would I feel at this point? Release? Pain? Blind terror?) Yes, it seemed that one could either prepare or not.

In autumn, we made our way through the DIY jobs. I bought a pot of wood filler and began repairing the window frames, seeking out the little nicks and cracks where moisture builds, digging out the rotten wood and scraping the hollows, then filling them with a putty that dried as quickly as I worked.

We packed insulation into the dust-filled loft; patched up the plaster in the bedroom. Soon a man came to mend the tiles on the roof; another rewired the kitchen. Meanwhile I cleared out the shed and pulled at weeds in the garden, uncovering as I did the evidence of other creatures: packets of vegetable seeds bitten into by mice; woodworm in a cupboard door; slug trails winding around the plant pots.

One morning, pulling a cabbage from the veg box and stripping its mottled outer leaves, I came across a clutch of eggs – tightly packed, anaemic-looking. A larva sprung and coiled. I yelped. Reached for a large kitchen knife and lopped them off, shocked at the sight of this secret work, this mysterious and strange labour that some ancestor of mine had long ago selected to keep inside them.

At sixteen weeks the foetus was avocado-ish sized, and the extra heart inside me was capable of pumping over 28 litres of blood a day. The diaphragm contracted and relaxed, contracted and relaxed, submerged in its salty fluid. The hands flexed, formed fists.

—Did you know, I asked my boyfriend, wanting somehow to involve him in the physical experience. —Did you know, I said, being pregnant is like running a forty-week marathon? Did you know the feet get bigger during pregnancy, as does the heart?

Did you know became my mantra. As in, you’ll never believe. As in, let me amaze you. The world is extraordinary. The world is extraordinarifying. If the mother doesn’t get enough calcium in pregnancy, the foetus will begin drawing it from her bones.

The bump was getting bigger. The kind of bigger that prompted polite, weary-looking men to get up from their seats on busy buses; prompted people to carry things, open doors.

My friend Dan, visiting the house, spotted the development chart hanging in the kitchen and remarked that it might be funny to make one measuring foetal size in relation to electronic devices.

Seventeen weeks: a smartphone.

Twenty-two weeks: an iPad.

—But no one would, would they? Dan said. —No one would buy it.

We sat on the sofa and picked slices of mango from a plastic packet. —Anyway, it’d be back to front, he said, stretching his legs. —Smaller is better in technology terms, right? I mean, you’d begin with nanotech and end up with what, a PC?

He had a point. Who wants to imagine their unborn child in terms of lithium and silicon and polycarbonate parts? We want them untainted, I suppose – and to preserve the innocence of that floating, uterine world.

The chart was not just about size, then, but association. A healthy foetus was Nature’s fruit – satisfying and wholesome! An image that confusingly brought to mind ingestion, not gestation, so that my ritual on turning a new page each week was to go out and buy the pictured fruit.

Dan had a daughter of his own, and she’d arrived early – they didn’t even have a cot or a car seat ready. —Be prepared, he warned solemnly, as he left the house that day, so after we’d said goodbye I resolved to pull out my laptop and get to it.

A maze! A vast, sprawling maze of safety features and comfort ratings and special one-day discounts. I scrolled and I scrolled, and was snagged, and thrown into blind, covetous comparisons, and backtracked, and scrolled again. There were algorithms, clearly, and a lexicon – a language through which sellers communicated with people like me. With the type of person I’d led them to believe I was. The natural world, as it happened, featured heavily. Soon I’d picked up a pen and begun making a list of keywords: pure, simple, organic, natural; plastic- and cruelty-free.

There were biodegradable baby wipes and bamboo bowls; organic swaddle blankets and wooden rattles. The Nature on offer here evidently didn’t include the bacteria or parasites I’d been working so hard to protect myself from. No, this version was clean – serene, even – and pricey. Smiling mothers were pictured gazing at happy, perfectly formed infants. Here, it seemed, were the fortunate bodies: the ones that had succeeded in keeping out the bad Nature, and locked the good Nature in. But, I thought, the images were flat. Yes, there was a kind of monotony to them, perhaps because the version of naturalness (and indeed of motherhood) being put forward here felt strangely closeted.

I looked at the picture in front of me: a wooden mobile suspended over a baby’s cot. A carefully counterweighted arrangement of circus animals that one could imagine might bob and wobble pleasingly if placed beside an open window. But there was no window in this picture; there was no door. Nothing to suggest that a world even existed beyond the neutral tones of the nursery.

The animals dangled. The baby gazed. The suggestion seemed to be that in motherhood my range of focus would begin and end with what was directly in front of me; that my role lay in simulating this rather bland image of simplicity and calm.

I blinked at my shopping basket: three packs of wipes and a tub of nappy cream. The postman appeared at the window and jammed a bunch of letters in through the box, then sat a moment in his van.

At the sixteen-week scan, having asked if we wanted to find out the sex, the sonographer had proceeded to spend fifteen minutes hunting around for a penis – whereupon, unable to find one, he’d concluded that I was most likely carrying a girl. —That’d be my strong guess, he’d said. —That’d be my theory. Thus was her sex assigned in the first instance on the basis of an absence, a lack.

Now I smoothed my hand across the taut skin of my stomach. No, I thought. Not a lack, not here, not so far as I could tell. The foetus lunged and twisted and I kept my hand there, unsettled by the nursery, which was supposed to lure me in. Too much was occluded; too much was missing. I did not want to enter that room with its inert animals, its lack of air. I didn’t trust it.

Outside, the postman took a bite of sandwich, started up his van. Above, clouds bowled. The sun shone, and the bright green of the trees made me think of what secrets might be contained within the folds of cabbage leaves.

—Did you know, I asked my boyfriend, as I was lying in bed and he was getting dressed. —Did you know, I said —when the Surinam toad has laid her eggs, after the male has fertilised them, he lifts them onto her back, where a thin film of skin grows over the top, which the babies break through when they emerge?

—Huh, he said, pulling on his socks. —No, he said. —I didn’t know that. What’s a Surinam toad?

—Did you know also, I went on —some cockroaches carry their eggs around inside an ootheca, an egg case, which they attach to the side of their bodies, like a purse? And that the cichlid fish carries her eggs around inside her mouth? That the cuckoo catfish lays her eggs in the cichlid fishes’ nest, so the cichlid will do the brooding for her?

He’d padded off downstairs. I could hear him moving about in the kitchen. It was windy and raining outside; the lane was a muddy stream, scattered with sticks and stones and pieces of fallen tree. The seasons were shifting, and the nausea was fading – yes, it was definitely fading, and in its place new appetites formed. I wanted stories of motherhood’s deviations, its hidden transgressions and silent vastnesses; its weirdness and its wonders.

Female woodlice have a brood pouch similar to kangaroos; kangaroos have two uteruses and three vaginas but never grow a placenta. Their offspring emerge half-made, in an embryonic state – blind, deaf and bald.

Start off down a path like this and it soon becomes difficult to stop. Mice and rats have two separate uteri and a cervix for each. Tawny sharks also have two uteri and embryos capable of swimming between them – sometimes offspring poke their heads out of their mother’s cervix and glimpse the world beyond even before the point of birth.

During the summer heatwave, a curious phenomenon: a temporary spike in deaths by drowning. In the news, these are known as ‘bathing accidents’ – a term that gives them an absent-minded feel, like leaving the tap running, like dropping the soap in the bathwater. Not like the more dangerous impulse to be submerged, to go under – a state that most closely resembles our time in utero, except that there is no return to that place; there is no going back.

For anyone finding themselves trawling the internet for stories of animal pregnancy, there’s a particular meme you’re likely to come across again and again: The amniotic fluid of all mammals is remarkably similar to seawater. It’s quoted on holistic therapy pages and natural birthing sites, environmental campaign pages and nature blogs – the claim so ubiquitous as to have gathered its own momentum, its own truth. Sometimes, it comes accompanied by a coda: Amniotic fluid mimics the seas that nourished our ancient ancestors. How easy it would be, how neat, if we possessed this physical signature – this salty marker of our first origins. Instead, in actuality, a slight mismatch: amniotic fluid has a salinity of about 2 per cent; the oceans around 3–3.5 per cent.

A closer parallel might be this: by late pregnancy, amniotic fluid contains sugars, scraps of DNA, fats, proteins, foetal piss and shit. It holds life’s first debris – its first waste.

—Are you feeling connected with the baby?

Running through her list of questions, the midwife squinted at the words on her screen. I drew my feet under the chair, hooked one behind the other. —What, I asked —like emotionally? The question seemed mildly ridiculous. How to experience a connection with a being that was not yet separate from me? Her finger hovered over the computer key. There was clearly a right answer, and a wrong one. I paused. She glanced up; a look of kindness, or understanding, or pity. —Talk to her, she told me. —It’s good for developing the bond.

She ripped a square of paper from a large roll by the desk, laid it down on the bed next to her and gestured for me to climb up. The paper crinkled under my thighs as she took a tape measure and stretched it from belly button to pubic bone. —They hear everything, you know. Heart beating, stomach growling, air moving about in your lungs. She bent down to check the measure. —Whatever noises are going on around you. By now she’ll be able to recognise your voice. They did a study that proved it. Foetal heart rate quickens when the mother speaks.

Did you know, I whispered to my unborn child. Did you know, about the burying beetle?

The burying beetle Nicrophorus orbicollis builds its nest first by finding a dead meat carcass, then dragging it underground. Next the female lays her eggs on or inside the dead body, which might be – have been – a small rodent or a bird. Once hatched, the larvae are passed morsels of carrion by the parents, who chew the meat and partially digest it before feeding it to their young.

If they’d started out as escapism, these stories of mothering creatures were quickly developing the quality of something more urgent and necessary – of matter pulled, lightning quick, below ground. They were not about research in any straightforward sense. Instead, they melded with other thoughts; they mainlined seams of feeling, situating themselves firmly as part of the process – part of the preparation.

Scientists did a study recently in which burying beetle larvae were divided into two groups. One group was fed carrion that had been chewed and regurgitated by the parents, and one was fed carrion that hadn’t. The survival rate of the first group was significantly higher, the parents’ saliva apparently containing some kind of protective mechanism, not unlike the function of mammalian milk. This exchange of fluids, which persists long after birth, appears to be an essential component of parental care.

By March, I tired easily. I moved slowly, I took longer to do small things. I was constantly hungry, but struggled to eat much; my stomach filled too quickly, and my bladder was always overfull.

We were nearing the end of our DIY list. My boyfriend had started painting, and I’d been ordered out of the house – because of paint fumes, he’d said. I called him from the supermarket. Behind me, a woman pushed a screaming toddler in a shopping trolley.

—What the hell is that? —I’m on the fruit aisle, I told him. —Do you want cantaloupe or honeydew?

He was on the stairs. He was painting them dark grey. —I’m just doing the edges, he said. —I’m nearly finished. Cantaloupe?

I thrust the fruit into my trolley as he proceeded to ask for three things from the other end of the shop, its farthest wall.

Outside, in the carpark, the sky was clear. Pigeons lumbered over the tarmac, hurried by the wind. I stood a moment, feeling the air; the first gusts of spring. Here’s another thing I learned: the human brain changes in pregnancy. Key areas actually lose grey matter, in a process not of stupidification but streamlining. The brain spring cleans; it pares the parts it is most going to need, pruning neural connections so as to increase their efficiency. The areas selected are those related to emotion, bonding and social contact.

Back at home the stairs were still wet, and when I forgot this and walked on them my boyfriend was distraught. —Can’t you see? Can’t you see how hard I’m working to get everything ready?

Did you know, did you know. If pregnancy were much more energy intensive, the body would begin eating itself alive.

A pair of socks with charcoal soles. A drawer of T-shirts with increasingly stretched seams. As I walked by a man smoking outside the post office, he held his breath; I heard the long exhale once I’d passed.