9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

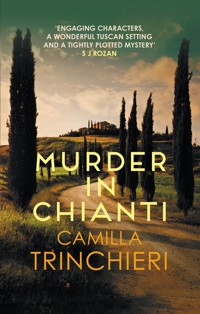

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Italian Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

'Engaging characters, a wonderful Tuscan setting, and a tightly plotted mystery'' S J ROZAN Mourning the loss of his late wife, Rita, former detective Nico Doyle moves to her hometown of Gravigna in the wine region of Chianti. He isn''t sure if it''s peace he''s seeking, but that certainly isn''t what he finds: early one morning he hears a gunshot near his cabin and walks outside to the sight of a flashily dressed man with his face blown off. Salvatore Perillo, the local inspector, enlists Nico''s help with the murder case. It turns out more than one person in this idyllic corner of Italy knew the victim, and with a very small pool of suspects, including his own in-laws, Nico must dig up Gravigna''s every last painful secret to get to the truth. 'A Tuscan feast of old lusts and new loves, meals and murder in Chianti country with an ex-NYPD cop and a dog' MARTIN WALKER, AUTHOR OF THE BESTSELLING BRUNO, CHIEF OF POLICE SERIES

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 463

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

3

MURDER IN CHIANTI

CAMILLA TRINCHIERI

CONTENTS

GRAVIGNA, A SMALL TOWN IN THE CHIANTI HILLS

6

CHAPTER ONE

Monday, 5.13 a.m. The sun wouldn’t show up for at least another hour, but Nico got out of bed, shrugged on a T-shirt, pulled on a pair of shorts and socks, and laced up his trainers. Bed had stopped being a welcome place, both back in the Bronx brownstone he and Rita had lived in for twenty-five years and here in this century-old, two-room farmhouse he’d rented since May.

He set up the moka and, waiting for the gurgling to start, made the bed. Since he’d begun making his own bed at the age three or four, he never walked away with it unmade. A neat bed started off the day with order, gave him the sense during childhood that all was well despite his father’s drunken temper, his mother’s fear. He knew it was all an illusion, but somehow it had helped then. And now, when he was trying to find order again. 8

A quick gulp of espresso shook him fully awake, followed by a forbidden cigarette that he smoked at the open window. Back in the Bronx flat, he had happily lived by Rita’s house rules. Now he had the unwanted freedoms that came with being a widower. Bad language when he felt like it, dressing like a street bum, a cigarette after morning coffee. An extra glass of wine or two with dinner. A good night-time cigarette. Small stuff that would never be worth it.

The air was still chilly in the early morning, which Nico welcomed as he set off for his three-mile run along the winding road up to Gravigna. It was steep going and dangerous in the predawn light. And even at this hour, cars whizzed past in both directions, their drivers on their way to work. But Nico’s morning run was like making the bed, a ritual that made him feel in control of his life, all the more necessary after the loss of his job, followed by Rita’s death.

When the town appeared, perched on its own small hill, Nico stopped to catch his breath and take in the view of Gravigna, with its medieval castle walls, its two towers, the proud steeple of the Sant’Agnese Church. In the meagre predawn light Nico could, with the help of memory, make out the hundreds of neat rows of vines that covered the Conca d’Oro, the golden bowl below the town that had once only grown grain. He had marvelled at the sight the first time he’d seen it with Rita on their honeymoon. ‘Our fairyland,’ Rita had said then, and he had laughed, both of them dizzy with love. 9

Every three or four years, whenever they could afford the trip, they’d come back. It had been her childhood home town. Rita’s parents, who had immigrated to New Jersey when she was six, had come back to die and be buried here. Rita asked to be buried next to them. He had obeyed, bringing her to her birthplace and immediately heading back. But he no longer had anyone in New York. An only child with parents long gone, ex-work colleagues who shunned him. And he missed Rita and her fairyland. He came back to be close to her and what family she’d had left – her cousin Tilde and Tilde’s daughter, Stella.

A pink-grey light had begun to scale the surrounding hills. It was time to go back and prepare the tomatoes. No going off in his old Fiat 500 to the town’s only cafe, Bar All’Angolo. The friendly bar owners; the schoolchildren, mothers and workmen crowding the counter; and the tourists sprawling over the tables made him feel less lonely, and the delicious whole wheat cornetti that came fresh from the oven made the place all the more tempting.

This morning, however, Nico was happy to break his routine. He had a job to do. Instead of his usual slow walk back, he started to jog home. Twin motorcycles rent the silence of the morning with their broken mufflers. A few cars passed, one honking loudly to announce its presence behind him. Another, a Panda, whizzed past, only a few inches away. Just another crazy Italian driver. Nico reached the stairs of his new home with a wildly beating heart and no breath left in his lungs. Maybe he 10was too old now for round-trip jogs. As he stretched his calves, he looked up at the sky. A cloudless blue vault, the start of another glorious Tuscan September day.

The dog relieved himself against a tree and meandered into the woods, sniffing for food that hunters or lovers might have dropped. The snap of twigs was followed by a chain of snaps. The dog froze, its ears at attention.

‘Where are we going?’ a voice asked.

The dog silently crouched down under a bush.

‘I know these woods,’ another voice answered. ‘I’m taking you to the meeting place.’

‘Why here, and why at this ridiculous hour?’

‘You wanted privacy, didn’t you? You’ll only get that in the woods, when everyone is asleep. If it were hunting season, we couldn’t even come here.’

‘We’ve already been walking for half an hour.’

‘Consider it a step towards repentance.’

‘It hasn’t been easy to live with what I did.’

‘You’ve certainly waited long enough to make amends, but don’t worry. The money will be enough to wipe away even your sins.’

‘Are you sure this will happen? I have to fly back tonight.’

‘Shh. Relax. You’ll get what you came for.’

A ten-minute shower restored Nico. Cargo pants, a clean shirt, bare feet and he was ready. The previous night’s pickings from the vegetable garden he’d started as soon as he’d signed the lease for this place awaited him in the room that served as both a kitchen and living 11area. Two baskets of ripe, luscious plum tomatoes sat on the thick pinewood table. He picked one up, felt its weight in his hands. A lot of work and love had grown these beauties. Nico turned on the oven and started slicing the tomatoes in half. After salting them, he drizzled extra virgin olive oil gifted from his landlord’s grove, added a spattering of minced garlic, and spread them, cut-side down, over four trays.

A gunshot rang out just as Nico was sliding the first tray into the oven. The sharp crack made his arm jerk. Tomatoes spilt to the floor.

‘Shit!’ Hunting season wasn’t opening for another week, but some hotheads were too eager for boar meat to follow the law. Aldo Ferri, his landlord, had warned him about the boars showing up en masse now that the vineyards were loaded with ripe grapes. The farmhouse Nico was renting was close to a dense growth of trees, the beasts’ favourite habitat. They were mean, ugly animals who could grow to weigh over two hundred pounds. Aldo had suggested Nico pick up a hunting rifle to be on the safe side. No, thanks – he was through with guns of any kind. Last night was the first time he’d heard gunshots. They’d come in short, distant bursts. This one had been much closer.

Only one shot. If this guy was after boar, he must be a damned good marksman. A wounded boar would spare no one.

Nico stared down at the tomatoes on the floor. Some had landed on his shoes. Hell, what was the rule? Thirty seconds? A minute? Well, Rita would have to forgive 12him. He’d swept the kitchen two days ago, and he needed every single tomato for the dish Tilde was letting him cook at the restaurant tonight.

With the tomatoes back in the oven to roast, it was time to enjoy the rest of this new morning. Nico ground some more coffee beans, put the moka over a low flame, cut two slices of bread, and filled them with thin slices of mortadella and a sheep’s milk caciotta. Probably a lot more calories than two whole wheat cornetti, but not caring about that was one of his new freedoms. He put his coffee and the sandwich on a tray, shrugged on a Mets sweatshirt, and stepped out to the best part of the house: an east-facing balcony overlooking part of the Ferriello vineyards and the low hills beyond.

There was just a slim ribbon of light floating over the horizon, enough light to see that the wooden beams holding up the roof were empty. No sleeping swallows. They didn’t usually fly off so early. That gunshot must have scared them away. Or maybe early September was simply time to move on. He would miss them, if that was the case. The evenings that Nico wasn’t helping Tilde at the restaurant, he’d got used to sitting out on the balcony with a glass of wine to wait for the three swallows to swoop in and tuck themselves in between the beam and roof for the night. He didn’t mind cleaning up their mess in the morning. They’d become fond of each other.

Nico was halfway through his breakfast sandwich when he heard a dog yelping. A high-pitched, ear-busting sound that could only come from a small breed. Maybe it was the mutt that seemed to have made a home next 13to the gate to his vegetable garden. A small, scruffy dog that always greeted him with one wag of his bushy tail and then lay down and went to sleep. Nico had checked the garden the first time to see if the dog had done any damage. Finding none, he let it be.

Nico leant over the balcony and whistled. The yelps stopped for half a minute, then started off again, louder this time. Nico whistled again. No pause this time. As the yelps continued, Nico wondered if the dog was hurt. More than possible. The vineyard fences were electric. Or it could’ve got caught in some trap. The yelps seemed to be coming from the left, past the olive grove. What if a boar had attacked the dog?

With hiking boots on and the biggest knife from his new kitchen in hand, Nico traced the sound of the yelps. They led him past the olive grove, up a small slope of burnt-out grass and into a wood thick with scrubby trees and bushes. The yelps got louder and faster. He was getting close. Then silence. Even the birds were mute. Nico broke into a run.

The dog almost tripped him. There it was, between his boots, with a single wag of its tail. ‘What the—’ The dog looked up at him with a perky expression that clearly signalled, I’m cute, so pay attention to me. Toto, the cocker spaniel he’d had as a kid, used to give him that exact same look whenever he wanted a treat.

‘I got nothing on me.’

The dog raised a paw. It was red.

Nico bent down to get a better look. Blood. On all four 14paws. The thick undergrowth had masked the prints. He checked the animal for cuts. Nothing. It was filthy, but fine. The mutt must have found the spot where the boar or other wild animal had been hit with that one shot.

‘Come on, you need a clean-up.’ Nico tucked the dog under his arm and turned to walk back. The creature squirmed and fought his grip, letting out a growl. ‘Fine, suit yourself, kid.’ Nico put it down and kept walking. The dog stood in place and barked. Nico didn’t stop. The dog kept on barking. Nico finally turned around. Toto would do this when he was trying to tell him something. Once, it had been a nasty rat underneath the porch. No rats here, but maybe he should go along with it.

He turned around. ‘Okay. What?’

The dog shot off deeper into the woods. Nico trudged behind him. ‘This better be good, mutt.’

At the edge of a small clearing, the dog sniffed the air a few times, then lay down, his job complete. When Nico reached the spot, he let out a long breath. What the mutt had been trying to tell him was a blinder.

About twelve feet in front of them, at the far edge of the clearing, a man lay on his back, arms and legs spread out at an unnatural angle. What had been his face was now a pulpy mess of flesh, brain and bits of bone steeped in blood.

Nico’s stomach clenched. It wasn’t the sight that got to him – during his nineteen years as a homicide detective, he’d seen worse and quickly numbed to it. No, it was the surprise of finding a body here. He’d walked away from that job, his old life, and come to Italy to find peace. He 15wanted to be near Rita, near her family, and far from violent death. Murder seemed to have no place in the beautiful Chianti hills.

‘Come on, let’s get out of here.’ His phone was back at the house. Nico bent down and swooped the mutt back up. No protests this time. He took another long look at the dead man without getting any closer. This was a crime scene, and old habits persisted. To blow off a man’s face, you needed a shotgun, not a rifle. Close range, maybe four feet. So it was probable the victim knew his killer. Blood would have splattered all over him. Find the bloody clothes, and you had the perpetrator. Nico’s eyes scanned the ground around the body. No shell that he could see. Either the murderer had picked up his brass, or it was somewhere in the underbrush. Not his job to go looking. His eyes shifted back to the body. A six-footer at least, judging by the length of his torso and legs. Big belly poking out of his jeans and a grey T-shirt mostly covered in blood. Some dark-red letters on it, or was that more blood? Nico leant as far forward as he could without taking a step. Not blood. Two letters. AP. Blood covered the rest of the word or logo. At the man’s feet were gold running shoes spotted with blood. Michael Johnson sprinters. If this man had ever been a runner, it was a very long time ago. White socks peeked up from the Nikes. On his wrist, more gold – a very expensive-looking watch. Maybe a knock-off. Hard to tell, even up close. Chances were the killer hadn’t been interested in that. Unless something or someone had scared him away. 16

Nico looked down at the mutt huddled in the curve of his elbow. ‘You?’ He surprised himself by smiling. ‘Sure thing.’ He turned his back to the dead man and, with the dog tucked under his arm, started walking back to the house. About twenty feet back into the woods, Nico felt the ground soften. He looked down. He’d stumbled on a patch of wet ground. Elsewhere the ground looked perfectly dry. It hadn’t rained in days. Nico took another step and spotted an upturned leaf. It held water. Pink water. The killer must have washed himself. There was no water source that he could see. Nico continued his walk home. Solving homicides wasn’t his job any more.

Nico gave the dog what was left of his mortadella and caciotta sandwich and put it out on the balcony. He’d stick it in a bath later. He had a call to make: 112, the Italian emergency number, was the logical choice, but he’d prefer to talk to someone he knew first. Tilde was busy preparing lunch at the restaurant. She was a rock, but the news might upset her.

Maybe Aldo, his landlord, a cheery, likeable man who seemed to have a lot of good sense. It hadn’t taken much effort to convince him the run-down farmhouse that hadn’t been lived in for thirty years would make Nico a cheap new home.

‘Gesú Maria! On my land?’

‘I don’t know. I found him about two kilometres into the woods past the olive grove.’

‘Not mine, thank the heavens. The German who owned it died a few years back, and the heirs put it up for sale. I 17wanted to expand and had the ground tested two years ago. You can’t grow grapes on that land. Too loamy. Loamy soil makes for inferior wine. There’s a rumour that some—’

‘Who’s in charge around here?’ Nico interrupted. Aldo was a talker. ‘Polizia or carabinieri?’ He had no idea who was called when. All he knew was that the carabinieri were part of the Italian army, and that there was no love lost between the two police forces.

‘Carabinieri. I’ll call Salvatore, the maresciallo. The station is in Greve. If he’s there, it’ll take about twenty minutes for him to make the trip.’

‘Thanks. I’ll wait here.’

‘I’ll bring him over. Thanks for letting me know. Wait till I tell Cinzia. She’s going to flip out! We’re booked solid today. Seventeen Germans—’

‘Someone has to get over there fast. Every second counts in a homicide investigation.’

‘You sound like a TV detective.’

‘I just want my part in this to be done.’

‘I’ll call Salvatore right away.’

‘Thanks.’ Nico put down the phone. He had to keep in mind that Tilde was the only one who knew he’d ever been a cop. And only a patrol officer, which was what he’d been when she had first met him. Rita had sworn her cousin to secrecy, afraid the townspeople would shun him. The Rodney King beating had happened only a few months earlier.

Sitting on a stone trough by the front door, Nico smoked the one of the two-a-day cigarettes he hadn’t 18been able to enjoy earlier. The mutt lay at his feet, snout between his still-bloody paws. Clean-up could wait. The dog was a part of the crime scene. So were Nico’s hiking boots. He’d changed into trainers, his boots next to the mutt. It was just past eight. The sun was warming things up, not a trace of cloud in the sky, and the tomatoes were nicely charred and out of the oven. He took another drag and felt the tension release. The morning’s discovery would soon be over. A walk and a talk with this maresciallo, and he would return to his new Tuscan life.

A dark blue sedan with distinctive red stripes on its hood appeared at the top of the dirt road that led to Nico’s rustic house. Nico quickly stubbed out his cigarette, forgetting that no Italian was about to tell him he was killing himself. The dog sat up and started a series of high-pitched barks.

‘Shut up.’

The dog looked at Nico with what he would swear was a puzzled expression.

‘You heard me.’

One last bark in protest, and the dog lay back down.

‘Good boy.’

Christ! A man’s face had been blown off not more than a few hours ago, and here he was, acting like his eight-year-old self when his mother had brought home Toto. Nico raised his hand to acknowledge Aldo in the back seat. In front were two men, the driver’s blonde head tall above the steering wheel and the front passenger’s head lying low. 19

Aldo came out first. He was a big man in his late forties with a round, jovial face and a wine-barrel paunch. He was wearing tan slacks and a bright leaf-green T-shirt with the purple logo for his wine on it. He waved back at the car. ‘Who would have thought we’d have a murder on our hands today, eh, Salvatore?’

A dark-haired man in a tan shirt and jeans stepped out of the passenger seat. A black nylon jacket was tied around his waist. ‘The murder is in my hands, Aldo. Yours have to make good wine.’

The maresciallo walked towards the house, recognising the man out front from his last visit to Bar All’Angolo. He had assumed then that he was just another American tourist, a man who’d held no interest for him. Now he saw the man as loose-limbed, big-shouldered, at least two heads taller than himself, on the short end of sixty with retreating grey-brown hair. He did not have the open, optimistic face he observed on so many Americans. Kind, naive faces bad at spotting danger. People who kept their wallets or cameras within easy reach of a thief and then came to the carabinieri with hope in their eyes. Hope the maresciallo was rarely able to reward. This man’s face was closed off, though there was intelligence in his eyes, which were the colour of steeped tea leaves. Had he only discovered a body this morning, or did he have something more to do with it?

The officer was somewhere in his forties, at the most five foot six, with a full head of hair black enough to 20seem dyed. A stocky, muscled frame and a chiselled face, handsome, with large liquid eyes, thick lips, an aquiline nose. A face Nico had seen before but couldn’t place. The man was smiling.

‘Salvatore Perillo, Maresciallo dei Carabinieri. I should wear uniform, but no time.’ Up close, Nico saw that Perillo’s hair had too much shine to be dyed. Perillo offered a hand. ‘Piacere.’

Pleasure it’s not was on the tip of Nico’s tongue, but he stopped himself. He conformed to Italian politeness and shook the hand. ‘Nico Doyle.’ Perillo’s grip was strong enough to crunch bone. Nico squeezed back.

Perillo nodded as if to acknowledge a tie, then took back his hand. ‘I have questions, but forgive, my English not so good.’

Before Nico could explain, Aldo stepped between the men and said in Italian, ‘Nico’s Italian is good. Italian grandmother, Italian American mother and Tuscan wife. Accent American.’ He grinned, seemingly happy to impart information the maresciallo didn’t have. Nico recognised the same proud tone Aldo used to explain the mysteries of wine-making to the busloads of tourists who came to his vineyards.

The fact that Nico was pretty fluent in Perillo’s language didn’t seem to affect the man one way or another. ‘And the father?’ Perillo asked in Italian.

‘Irish,’ Nico answered in Italian.

‘An explosive combination, I’ve been told.’ The maresciallo’s Southern accent was strong.

‘You’ve been told right.’ 21

‘I usually hear the truth when I’m in civilian clothes. With the uniform, not so much.’ Perillo looked down at the dog sniffing at his heels. ‘Is that blood on his paws?’

‘Yes, the dead man’s. The dog led me to the body.’

‘Yours?’

Nico found himself answering yes.

Perillo bent down and scratched the dog’s head. He got the one wag for his trouble. ‘What’s his name?’

Toto was the first idea that popped into Nico’s head. No good. And they were wasting time. ‘I call him OneWag.’ He used English words for the name. To say the same thing in Italian would have required too many letters. ‘I’ll show you the way now.’

Perillo eyed him for a moment. Nothing showed on his face, but Nico suspected the maresciallo was surprised he’d taken the initiative. ‘Yes, please lead the way. My brigadiere will stay here with the car. Is it far?’

‘About three kilometres into the woods.’

‘Ah, the woods!’ Perillo’s glance went down to his own feet. He was wearing brown suede boots that looked brand new. ‘At least it hasn’t rained.’ He gestured towards the woods. ‘Please. I will ask questions as we walk.’

‘Maybe it’s faster,’ Nico said, not used to being on the receiving end of an interrogation, ‘if I explain and then you ask questions.’

Perillo seemed amused by this. ‘The Americans are prisoners of speed. Tuscany, the whole Italian north, is closer to the American way of thinking, but I come from Campania.’ They started walking, Aldo trailing behind them, OneWag running ahead. Nico was surprised 22Perillo was letting Aldo tag along. The fewer people on a crime scene, the better, but again, he reminded himself, it wasn’t his investigation.

‘We have a different approach,’ Perillo was saying, ‘although in this case, you are correct. Time brings heat, flies, maggots. I’m sure it was a very unpleasant sight in the first place, one perhaps you are not eager to repeat and therefore wish to be over with. Best to deal with it quickly. As for understanding the story behind this death, I fear speed will not be possible. Our investigations are not like on Law & Order or CSI. And so tell me, Signor Doyle,’ Perillo said, addressing Nico using the formal lei, ‘what facts are you so anxious to remove from your thoughts?’

‘A few minutes after seven this morning, I heard a single gunshot. It sounded fairly close by. I assumed it was some hunter who couldn’t wait for the season to start. But it could be the shot that killed this man.’

‘We will see. No need for you to speculate.’

‘Of course.’

‘Please continue, Signor Doyle.’

‘Please, call me Nico.’

‘For now, let us keep up the formalities.’

They stepped into the woods. There was no path. Nico was grateful that OneWag led the way. Under different circumstances, the walk would have been a pleasant one. The morning silence was now broken by bird chatter, the dark underbrush splotched with the sun breaking through trees. A light breeze ruffled the leaves. While Perillo kept his eyes on the ground, careful of where he 23placed his new suede boots, Nico explained that he’d been led to the body by the dog’s desperate-sounding yelps. ‘I thought he was hurt.’

‘Where were you when you heard the dog?’

‘On the balcony, having breakfast.’

‘If the body is three kilometres into the woods, you have very sharp ears.’

‘OneWag has a very sharp voice. It was early and quiet. It’s possible I was on alert because of that gunshot. Just one – that surprised me. When I heard the yelps, I followed them and saw the mess. On my way back, I found a patch of wet ground and some pinkish water. My guess would be that the killer washed some blood off there. I don’t remember where it was, exactly.’

‘We’ll find it. Did you step in it?’

‘Yes. You’ll want my boots.’

‘Indeed,’ Perillo said, looking at Nico with renewed interest. OneWag’s barking stopped Perillo from going any further.

‘It’s just there,’ Nico said. ‘In the clearing behind those laurel bushes. The dead man’s at the far edge.’

‘Stay here, both of you, and hold the dog,’ Perillo ordered. He squared his shoulders and walked ahead with a determined step.

The maresciallo was first overtaken by the thick metallic smell of blood and the frenzied buzz of the flies. And then he saw the body at the edge of the clearing. He shrank back a step, closed his eyes and crossed himself. It was indeed an ugly sight. What had he said earlier? 24Time brings heat, flies, maggots. I’m sure it was a very unpleasant sight in the first place. He regretted his pompous tone. It was an unpleasant trait that always surfaced with strangers. What Signor Doyle had discovered was a gruesome act of hate. The dead man’s face and half his brain blown away, spread across the grass like pig fodder.

Who was this poor soul? What had he done to deserve such violence? Certainly not a local, not with those shoes. Perillo took off his new boots, his socks. He had forgotten shoe covers. Bare feet were easily washed. He took out rubber gloves from his back pocket and slipped them on.

Slowly, he walked in a wide arc below the man’s legs, trying to remain on clean grass. He circled the legs and stopped near the man’s hips. Perillo reached into the pocket. It was empty. He leant over the body and tried the other one. It had nothing that would tell him the identity of this poor man, but deep inside he found a hard object. He pulled it out, careful not to move the body, and studied it in the palm of his hand. With some luck, it would lead him to some answers. Luck and hard work.

Perillo slid the object into an evidence bag and took out his mobile phone. He punched in the number of headquarters in Florence.

Nico bent down and tucked OneWag under his arm, receiving a lick on the chin for his effort. Aldo waited a few minutes before tiptoeing forward. 25

‘Oh my God.’ Aldo’s knees buckled as he peered beyond the bushes.

‘I did warn you,’ Nico said.

Aldo backtracked slowly, wiping his face with a handkerchief. ‘You think he got shot in the face so he wouldn’t be recognised?’

Nico had wondered about that himself. ‘He may have had ID in his pockets.’

‘You didn’t look?’ Aldo’s hands kept kneading his handkerchief.

‘I know not to mess up a crime scene.’

Aldo looked at his watch. ‘I’ve got to get back. Seventeen Germans coming for a wine tasting and lunch, and forty Americans busing in from Florence for dinner. It’s going to be a hard day.’

‘The hard day’s mine, Aldo.’ Perillo walked through the laurel bushes with his suede boots and socks tucked under his arm. ‘This murder makes it a good day for you. You have a much better story to tell your guests than how wine is made.’ His tone was jovial, his face anything but. ‘Regale them with a few details, they’ll be thirsty for more, and you’ll sell some extra bottles. Go home and enjoy a few glasses of your Riserva. It will erase the ugly sight you insisted on coming here to see.’ He turned to Nico, who was staring at his bare feet. ‘Blood and suede is a disastrous combination, Signor Doyle.’

Aldo asked, ‘Did you find ID on him?’

‘No. He was wearing white athletic socks and gold running shoes, which makes me think he’s an American, although I might avoid telling that to your guests. He 26was also wearing a gold Breitling watch, worth around five thousand euro.’

‘That eliminates robbery as a motive,’ Aldo said.

‘Possibly, if he was the kind of man who went around without a mobile phone, wallet, credit card or driver’s licence,’ Perillo said, ‘although one can be robbed of many things besides expensive accessories. Their life, for one.’ He turned to Nico. ‘Thank you, Signor Doyle, for being my Cicero on this terrible occasion. I am sure your expectations of Tuscany did not include a gruesome death. I do request that you give your boots to my brigadiere, who is by the car. I also need you to come to the station in Greve this afternoon for a deposition. At that time, I will take your fingerprints and a DNA sample.’

‘My fingerprints are on my residence permit, and I didn’t go anywhere near the body.’

‘I don’t doubt your word, but nevertheless. The DNA requirement is fairly new and meant to eliminate confusion. A good idea, for once. We Italians often make more confusion than is strictly necessary. As for your fingerprints, it will save time. It takes a while for the carabinieri to gain access to residence permits. Leave the dog with me, please. He may have picked up something of interest in his paws and fur. The technical team and medical examiner are on their way. Don’t forget, Signor Doyle. At four o’clock. The signage in town is clear. You won’t have a problem finding the office.’

Nico glanced at the dog, who looked back with a sharp tilt to his head as if he knew something was up. ‘I 27don’t have a lead for him.’ He was having a hard time letting him go. ‘I could stay here until they come.’

‘We cannot have you stay here while we do our work. Lay aside your fears. We will treat him with hands of velvet.’ Perillo undid the nylon jacket tied to his waist and lay it flat on the ground. ‘Put him here.’

Nico did as he was asked. Perillo quickly zipped up the jacket around the dog, tied the sleeves and lifted the bundle up. OneWag peeked out of the opening and barked at Nico.

‘Go home, Aldo. You too, Signor Doyle.’

Nico gave OneWag a quick scratch behind his ear and turned to go. The dog barked louder.

‘Try to forget what you have seen here. It is not representative of our beautiful country.’

Nico could not help thinking of all the Camorra killings he had read about in Perillo’s neck of the woods, but the maresciallo was right about his expectations of Tuscany. They did not include murder or a stray dog.

CHAPTER TWO

It was eleven-thirty when Nico arrived at the restaurant with his pan of roasted tomatoes. At noon, Sotto Il Fico – Under the Fig Tree – would open for lunch.

‘Buongiorno,’ Nico said.

‘Not for everyone, I hear.’ Elvira, Tilde’s mother-in-law, was in her usual armchair at the back of the narrow front room, which held the bar and a few tables. The draw of the restaurant was its large hilltop terrace, which held a huge sheltering fig tree and a serene view of a patchwork of perfectly aligned grapevines below. Elvira was wearing one of her seven housedresses – she had one for each day of the week. Today’s was white with red and pink checks. She was a widow with crow-black dyed hair, a corrugated face that made her look older than her sixty-two years, a small, sharp nose and piercing water-blue eyes that didn’t miss a single trick. Rita had nicknamed her ‘the seagull’ 29for the way she seemed to hover around people, looking for titbits to snatch up.

‘Salve.’ Behind the short bar by the door, her son, Enzo, Tilde’s husband, reached for a grappa bottle. He had his mother’s angular face and black hair streaked with grey, and always wore jeans and a Florentine football team’s T-shirt. He poured grappa into a small glass and held it out. ‘Poor Nico. This will restart your motor.’

So the news had already got out. ‘No, thanks, I’m fine,’ Nico said.

‘I wouldn’t be fine.’ Enzo drank the grappa in one swig. ‘No one’s ever been murdered in Gravigna.’ He gave the grappa bottle a longing look but put it back on the shelf. ‘All over the world, people are killing each other for no good reason. This country is drowning in shit, and now there’s a murdered man in our woods.’

‘I’m sure it wasn’t anyone you knew.’ From what Nico had learnt of the town, only Sergio Macchi, the butcher with two restaurants, was rich enough to afford that watch, and Sergio didn’t have the dead man’s belly.

‘Of course not.’ Elvira turned her gaze on Nico. ‘I hear the dead American had no ID.’

Nico walked up to her. ‘Who says he’s American?’

‘I do,’ Elvira declared. ‘He was wearing gold trainers and thick white socks. You can always tell someone’s nationality by his socks and shoes. Germans and Scandinavians wear brown or grey socks with sandals, of all things. Asian women wear little socks with drawings on them and feminine heels. The English, argyles and sensible leather shoes.’ 30

Nico lifted up his pan. ‘I’d better get this into the kitchen.’

‘I was hoping you’d changed your mind about that dish of yours. The tourists want Tuscan food, not something invented in the Bronx.’

‘Rita invented it, and she was Tuscan.’

Elvira waved him away. ‘Go on, get yourself in the kitchen. Tilde thought you’d chickened out.’

‘I did not!’ called a voice from the kitchen.

‘Ever since she heard about the murder, she’s been acting like she’s walked into a wasps’ nest.’

‘Mamma, she’s upset. We all are.’ Enzo reached back to the shelf and poured himself another grappa.

Elvira shook her head and went back to folding napkins. Nico sometimes marvelled at the relationship between the two women. It wasn’t exactly a positive one, surprising considering how closely they worked together. Elvira owned the restaurant, and her contribution to the place was folding napkins from a rickety gilded armchair rescued from the dump – one that she would forever claim a Roman contessa had bequeathed her. When she wasn’t folding, she solved the crossword puzzles in the weekly Settimana Enigmistica, eyes ready to snap up at every arrival. Enzo, her forty-year-old son, manned the bar and cash register. When he was feeling energetic, which from what Nico had seen wasn’t often, he’d slice the bread as well. Tilde and Stella ended up doing the hard work, cooking and serving with part-time help from Alba, a young Albanian woman. Nico was only too happy to lend a hand. 31

Tilde was in the kitchen, a long, narrow room with scarred wooden counters and walls covered from hip level to ceiling with worn copper and steel pots and pans. She was rapidly slicing mushrooms for her apple, mushroom and walnut salad, a lunchtime bestseller. She pecked Nico’s cheek while spritzing the just-cut slices with lemon juice. ‘I heard. Sorry you had to go through that.’

‘You mean Elvira or the dead man?’

That got a half smile out of her. ‘Both. Are you okay?’

‘Yes.’ Nico put the pan of tomatoes in a far corner. He didn’t need them until this afternoon. ‘Are you?’

‘The wasp bit me, but then it died.’

Nico grinned. ‘I believe it. We all know you’re armoured in granite, but it’s still only armour. Having a murderer nearby is scary. There’s nothing wrong in admitting that.’

Hearing about the murder was horrible, but it was mention of the dead man’s shoes that had stuck a knife in her chest. It had been twenty-two years. Tilde had managed to almost entirely erase the thought of Robi, but now his drunken boast haunted her. I’ll return covered in gold.

‘Was the dead man really wearing gold trainers?’ she asked.

‘Yes, and a big fat gold watch.’ Nico walked past the small window overlooking the dining terrace and saw Stella under the fig tree, setting tables. He waved at Rita’s goddaughter. ‘Ciao, cara.’ He was hoping 32for her usual heart-warming smile but only got a nod. Understandably, the murder had got to her too.

‘Let me do this.’ Nico slid the pan of courgette lasagne ready for the oven to one side and stood next to Tilde.

She handed him the knife. ‘Very thin. And don’t forget the lemon.’

‘Yes, I know, I know.’ It wasn’t the first time he’d done the slicing. ‘I’m aware that news travels fast in a small town, but how did Elvira know about the socks and shoes?’

Tilde waved a dismissive hand in the air. ‘She found out from Gianni. He works for Aldo. I thought you knew that.’

Gianni was Stella’s boyfriend, a handsome young man with the arrogance of youth. Stella liked him as much as Tilde disliked him. Tilde stirred a pot of cooling navy beans that she would serve with tuna and the sweet red onions from Certaldo, Boccaccio’s home town. Beans of any kind were a staple of Tuscan cooking.

Tilde offered him a spoonful of the beans. ‘You need reinforcement after what you’ve been through. Help yourself to anything.’

He was being offered food as tranquilliser. Looking would have to be enough for now.

Next to the pot was another Tuscan staple, also a Sotto Il Fico bestseller – pappa al pomodoro, a thick soup of stale bread, tomatoes, garlic, basil and vegetable broth, topped by a generous squiggle of extra virgin olive oil. Tilde’s pappa surpassed all the others he and Rita had tasted over the years. If Tilde had a secret ingredient, she 33didn’t share. Every time he walked into the kitchen, no matter the time, the pappa was already made.

Tilde saw him eyeing the pot. ‘Maybe someday I’ll tell you,’ she said.

‘I won’t hold my breath.’

‘That’s wise. Does Salvatore know you were a police officer?’

‘No, and you’re not going to tell him. You’re on a first-name basis with him too?’

‘Everyone knows him. He goes to Bar All’Angolo whenever he gets a chance. That’s where the cyclists hang out. He’s an avid cyclist. He and his pals sometimes drop by for a late lunch after a Sunday race.’

Cycling was an Italian passion, Nico had quickly discovered on his first visit. On the weekends, there wasn’t a road in Tuscany that wasn’t overrun by racing bikes either whizzing downhill or straining uphill.

Tilde said, ‘You must have seen him before.’

‘He did look familiar.’

‘Salvatore Perillo is a good man. Solid.’ She turned to look at Nico. She had a small face with wide, caramel-coloured eyes that softened her severe expression. The red cotton scarf wound around her head covered the same beautiful long, chestnut-brown hair that had been Rita’s pride before it turned grey. Tilde was forty-one, and her hair had not lost its rich colour. She had been a stunning, smiling beauty in the photos Nico had seen of her as a teenager. With the passing years, her soft beauty had changed into something harsher, unsmiling. And yet she claimed to be happy. Rita had blamed the change on too much work. 34

Tilde wiped her hands on the long white apron that sheathed her perfectly ironed beige cotton dress. Nico had never seen her in slacks or in a wrinkled item of clothing.

‘You could help him solve the crime,’ she said.

‘Why?’ The last of the mushrooms were done. He picked up a green apple.

He wanted to add I have no experience in solving crimes, but Tilde didn’t deserve a lie. The omission was bad enough. Tilde had never been told he’d moved from being a uniform to homicide detective.

When he’d protested years ago, Rita said, ‘You don’t know Italians. All they’ll want to talk about are your cases. It would ruin our holiday. You deal with such gruesome, ugly stuff, and I’ll never understand how you stomach it.’

He’d been angry at the time, unaware until then how much she disliked his new job. He didn’t have much stomach either for the gruesome part of homicide, he explained, but he wanted to right what was wrong, give the victims’ families justice.

Rita accused him of wanting to play God. He reminded her a detective’s salary was better than a patrolman’s. They’d hoped to start a family. Twenty years had passed since then.

Tilde opened a big jar of Sicilian yellowfin tuna. ‘We need this murder solved quickly. The whole town is scared, excited, curious. Enzo’s phone hasn’t stopped ringing. I had to turn mine off. Just what we need right now, for the tourists to get scared and leave. Besides, I’m worried you’ll get bored and go back to America.’ 35

‘It’s hard to be bored in such a beautiful place,’ Nico said. He was sad at times, which was to be expected. His footing here wasn’t solid yet, but he was working on it. When he wasn’t helping out at the restaurant one of his three shifts a week, he walked the streets, listening, striking up conversations at the bar, at the newsstand, at the trattoria in the piazza. He had nothing to take him back to New York. His police career was over. ‘You’re the only family I’ve got, and I’m staying right here. I like helping you with the restaurant.’

‘But I feel bad I can’t pay you.’

‘What I need is friendship, not money. Besides, you feed me when I’m here.’

‘We close in October and won’t reopen until April. What will you do then? Of course, you’re welcome to eat with us anytime you want, but still, the winter months here can feel very long.’

‘I’ll perfect my cooking skills and hire myself out to the competition.’

‘Such a man. Your dish tonight better be good.’

‘It will be. I wish I could reassure Stella she has nothing to be scared of.’ He’d been watching her weave through the tables with sagging shoulders, head down.

‘It’s not the murder. She had a fight with Gianni.’

‘Serious?’

‘Very, and I hope she has enough sense to break it off.’

‘That’s harsh. She loves him.’

‘She’ll get over it.’

Tilde’s angry tone made Nico pause and study her. He knew she loved her daughter very much, and he 36wondered what could make her dismiss Stella’s feelings so quickly. He watched her put the courgette lasagne in the oven and waited.

She slammed the door shut. ‘Stop staring at me. I’m not a witch. Stella has a university degree in art history, but Gianni wants her to stay here and be a waitress. Yesterday she disobeyed him and went to Florence to apply for the competition exam to be a museum guard.’

‘I would think her degree was enough.’ From what he’d seen of Italian museum guards, all they did was sit in a chair and make sure visitors didn’t get too close to the art. At least they had the advantage of sitting, a privilege American guards didn’t seem to have.

‘All state jobs can only be won by passing a competition with flying colours,’ Tilde said. ‘Even if Stella gets top marks, there’s no guarantee she’ll get it. Here, people get ahead because of nepotism or bribes. Stella wanted to teach art at the university level, but her professor wasn’t esteemed enough to mentor her, so now we have to pin our hopes on the guard job. A state job is good. I think they have about twenty openings and more than three thousand people are applying. I don’t hold much hope, but at least she should be encouraged to try. Gianni told her he’d leave her if she got the job.’

‘He’s just scared of losing her.’

She pointed a serving fork at Nico, eyes narrowed. ‘Don’t you side with him.’

It was the first time he had seen her this upset. ‘I’m just saying. Want me to talk to him?’ 37

‘No. I want her to get to her senses and leave him.’ Laughter and German words drifted in from the front room.

‘Enough talk,’ Tilde said. ‘Our first lunch guests are here.’

‘I’ll help Stella serve.’

‘You’re a gift from God,’ Tilde said with a peck on his cheek and a push out the door.

There had been quite a crowd at lunch today, thankfully unaware of the murder in the area. Nico and Stella were too busy rushing about to talk to each other until it was time for him to go to the carabinieri station. The maresciallo was waiting for him by now, but Stella was more important. They had just finished clearing all the tables. He took her hand and led her to a seat under the shade of the fig tree. Before sitting down, he kissed her cheek. ‘How are you?’

Stella was almost a young replica of Tilde. The same oval shape of the face, full mouth, straight nose, a fair, clear complexion, thick chestnut-brown hair she had just had cut to intentionally uneven lengths, one side covering her ear and the other barely touching the top of her ear. Nico had watched Tilde blanch when Stella came back from the hairdresser. ‘Good cut’ had been her only comment. What was different was the colour of her eyes, a transparent jade green that no one else in the family claimed.

Stella furrowed her brow. ‘Did Mamma ask you to talk to me?’

‘No. My feet hurt, and I want to see that beautiful smile of yours.’ 38

She responded with a quick, throaty laugh. ‘Sorry, I’ve dropped it somewhere and now I can’t find it.’ She leant over the chair and clasped her arms around his neck. ‘Poor Nico, it must have been terrible for you. Weren’t you scared?’

‘No reason to be. He was dead. I would say repulsed is more accurate. What’s truly horrible is the cruelty we are capable of.’

She dropped her arms. Fingers started twisting at the hem of her top. ‘It’s scary. You found him in the woods behind Aldo’s place, right? Mamma has always forbidden me from going there by myself. I don’t know why. Nothing bad’s happened there before today. Gianni thinks it’s just a power play on her part. Says it’s a great place to pick mushrooms.’

‘And I suspect a good place for lovers too.’

Stella shook her head. No smile, no blush. ‘There are other places. I do wish Mamma and Gianni got along. I feel pulled in two.’

‘She’s thinking of your future.’

‘I know. So am I, and Gianni’s being a perfect pill about it. Zio Nico, are you sure you’re okay?’

‘I am, and please don’t be scared. The carabinieri will find the killer quickly.’ Nico stood up. ‘Ciao, my bella. Thanks for worrying about me.’ He kissed her cheeks. ‘See you tonight. You’ll have to tell me if you like my dish.’

She stood up too, pulled the now wrinkled hem of her top down over her jeans. ‘I’m sure it will be delicious, and there will be none left for us.’ The shadow of her beautiful smile appeared on her face. 39

‘Ah, the light is coming back.’

‘Your doing. I love you.’

‘Me too.’

A quick hug and he walked away. He was going to be very late for his appointment.

Nico got on the panoramic 222 road that snaked from Siena through the Chianti hills, ending just south of Florence. The 500 started belching as soon as he floored it, and what should have taken only fifteen minutes took twice that. He knew from the start that the price Enzo had asked for the car was over the top, but they both understood that Enzo was asking for help in buying a new espresso machine for the restaurant, and Nico had gladly paid. Now he felt like cursing.

Once on the main road in Greve, the car stopped belching, but traffic slowed to bumper-to-bumper pace. He read the banner flying over the street. The reason for the traffic jam became clear. The Chianti Classico Expo, the biggest wine-tasting event in the region, was starting in three days. As he neared the intersection that led to the big medieval piazza that was the heart of the town, he heard shouting punctuated by hammer blows. He had read about the event in the local paper, but this morning’s discovery had wiped it from his mind. Even if he’d remembered, he hadn’t been about to leave Stella with more than thirty diners to take care of all by herself. For once, even Enzo had been busy pouring glasses of wine and making espresso drinks at the bar. There was nothing Nico could do about it now. The maresciallo 40would understand. Or not. He didn’t care. This was a courtesy. Anyway, Italians were always late.

The red light was taking forever to change, and he couldn’t see any signs telling him where to go. Nico leant out the window and asked a woman overloaded with shopping bags where he could find the carabinieri station.

The middle-aged woman, dressed in a rumpled yellow linen suit, beamed at him. ‘Ah, thank the heavens. I will show you.’ She quickly walked in front of his car, opened the passenger door, pushed the bags to the floor, and dropped herself onto the seat. There was barely enough room for her.

Nico stared. She smiled. ‘Trust me.’

He hated those two words because they rarely delivered, but her face was kind, which reassured him. Not that he thought he was being carjacked. Manipulated, maybe.

The light changed to green.

‘Turn right here,’ the woman said, pointing a red-nailed finger. ‘Cross the bridge. Turn left at the next street. See the sign?’ She said it slowly, in a soft, low voice, as if addressing a foreign child. His accent had given him away.

Nico did as she said. Halfway up the hill, she asked him to stop. ‘I live in that villino.’ She extended a hand to him. ‘Maria Dorsetti.’ Nico shook it and mumbled his name. Something about this woman flustered him.

She did not ask him to repeat it. ‘Thank you for saving me the climb. At the top of the hill, turn right, then left. You’ll see a cafe to your left, a park to your right. The 41carabinieri station is just across the street from the park. I hope your business with them is not unpleasant.’ She tilted her head, waiting for him to respond.

He said, ‘Thank you.’

Clearly disappointed by his terseness, she gathered her shopping bags and struggled to get out of the small car. She waved at Nico as he took off.

As he climbed the hill, he noticed in his rear-view mirror that she stayed on the pavement and watched him drive off. Nico remembered the time he and Rita had got lost trying to find Dal Papavero, a famous restaurant in a village above Gaiole in Chianti. Rita had asked for directions from the only person they could find on the road – a teenager kicking around a football. The boy offered to take them there. Rita accepted before Nico could stop her. ‘He’s going to take us where he wants to go,’ he had muttered in English. Rita had laughed, her way of shutting him up. The boy got in the back seat, gave Rita directions, and seven winding uphill kilometres later, Dal Papavero came into view. The boy didn’t live in the tiny town, wouldn’t accept a meal or money. He said he did it because they were lost and he was bored. Rita watched him kick his ball back down the hill.

With dessert, a delicious torta della nonna, ‘grandmother’s cake,’ Nico had got a lecture on trust.

‘Buona sera, Signor Doyle.’ Perillo stood behind a large desk placed at the end of a deep room. The distance from door to desk gave him the time to study the people who 42came to complain, snitch, lie, or tell the truth. It gave him a head start.

Perillo watched the tall man stride confidently into the room. Not smiling, but at ease with his surroundings. Most people, even honest ones, were nervous walking into the carabinieri station for the first time. Not this man. Perillo had discovered several interesting facts about Signor Doyle, thanks to the Internet.

‘I’m sorry I’m late. I wasn’t expecting so much traffic.’

‘An apology is not necessary. Your dog is waiting for you under the desk. He behaved very well.’

‘Hi, pal.’ Nico bent down.

The dog ignored him. His coat had turned into sparkling white fluff. His paws were clean too. Some fur had been trimmed off.

‘Somebody gave you a bath.’ He reached down and stroked the dog’s long ears. ‘You look good.’

Still no response. Was he hurt? ‘What did you do to him?’

‘The technicians examined him with great regard. His fur was carefully combed out to catch whatever might have been trapped there. His paws meticulously scrubbed. I do not believe he will solve our murder, but it is best to be thorough. We also took an imprint of your boots. As you seemed anxious about the dog, I brought him back to your house when they were through. You weren’t present, so he came here. I was afraid he might run away. I left your boots by your doorstep.’