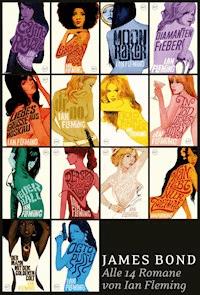

5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

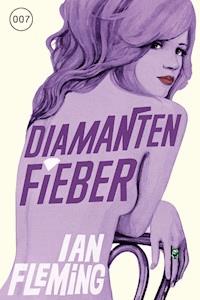

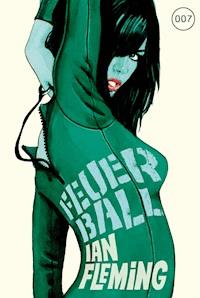

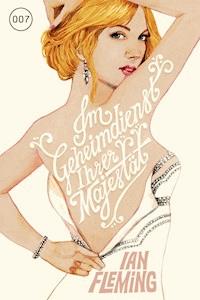

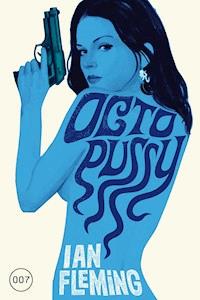

- Herausgeber: Ian Fleming Publications

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: James Bond 007

- Sprache: Englisch

Meet James Bond, the world's most famous spy.In the aftermath of Operation Thunderball, Ernst Stavro Blofeld's trail has gone cold—and so has 007's love for his job. The only thing that can rekindle his passion is Contessa Teresa "Tracy" di Vicenzo, a troubled young woman who shares his taste for fast cars and danger. She's the daughter of a powerful crime boss, and he thinks Bond's hand in marriage may be the solution to all her problems. Bond's not ready to settle down—yet—but he soon finds himself falling for the enigmatic Tracy.After finally tracking the SPECTRE chief to a stronghold in the Swiss Alps, Bond uncovers the details of Blofeld's latest plot: a biological warfare scheme more audacious than anything the fiend has tried before. Now Bond must save the world once again—and survive Blofeld's last, very personal, act of vengeance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 408

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

On HerMajesty’s SecretService

IAN FLEMING

ForSable Basilisk Pursuivantand Hilary Braywho came to the aid of the party

Contents

1: Seascape with Figures

2: Gran Turismo

3: The Gambit of Shame

4: All Cats Are Grey

5: The Capu

6: Bond of Bond Street?

7: The Hairy Heel of Achilles

8: Fancy Cover

9: Irma la Not So Douce

10: Ten Gorgeous Girls

11: Death for Breakfast

12: Two Near Misses

13: Princess Ruby?

14: Sweet Dreams – Sweet Nightmare!

15: The Heat Increases

16: Downhill Only

17: Bloody Snow

18: Fork Left for Hell!

19: Love for Breakfast

20: M En Pantoufles

21: The Man from Ag. and Fish.

22: Something Called ‘BW’

23: Gauloises and Garlic

24: Blood-Lift

25: Hell’s Delight, Etc.

26: Happiness without a Shadow?

27: All the Time in the World

1

Seascape with Figures

It was one of those Septembers when it seemed that the summer would never end.

The five-mile promenade of Royale-les-Eaux, backed by trim lawns emblazoned at intervals with tricolour beds of salvia, alyssum and lobelia, was bright with flags and, on the longest beach in the North of France, the gay bathing tents still marched prettily down to the tideline in big, money-making battalions. Music, one of those lilting accordion waltzes, blared from the loudspeakers around the Olympic-size piscine and, from time to time, echoing above the music, a man’s voice announced over the public address system that Philippe Bertrand, aged seven, was looking for his mother, that Yolande Lefèvre was waiting for her friends below the clock at the entrance, or that a Madame Dufour was demanded on the telephone. From the beach, particularly from the neighbourhood of the three playground enclosures – ‘Joie de Vivre’, ‘Hélio’ and ‘Azur’ – came a twitter of children’s cries that waxed and waned with the thrill of their games and, further out, on the firm sand left by the now distant sea, the shrill whistle of the physical-fitness instructor marshalled his teenagers through the last course of the day.

It was one of those beautiful, naive seaside panoramas for which the Brittany and Picardy beaches have provided the setting – and inspired their recorders, Boudin, Tissot, Monet – ever since the birth of plages and bains de mer more than a hundred years ago.

To James Bond, sitting in one of the concrete shelters with his face to the setting sun, there was something poignant, ephemeral about it all. It reminded him almost too vividly of childhood – of the velvet feel of the hot powder sand, and the painful grit of wet sand between young toes when the time came for him to put his shoes and socks on, of the precious little pile of seashells and interesting wrack on the sill of his bedroom window (‘No, we’ll have to leave that behind, darling. It’ll dirty up your trunk!’), of the small crabs scuttling away from the nervous fingers groping beneath the seaweed in the rock pools, of the swimming and swimming and swimming through the dancing waves – always in those days, it seemed, lit with sunshine – and then the infuriating, inevitable ‘time to come out’. It was all there, his own childhood, spread out before him to have another look at. What a long time ago they were, those spade-andbucket days! How far he had come since the freckles and the Cadbury milk-chocolate Flakes and the fizzy lemonade! Impatiently Bond lit a cigarette, pulled his shoulders out of their slouch and slammed the mawkish memories back into their long-closed file. Today he was a grown-up, a man with years of dirty, dangerous memories – a spy. He was not sitting in this concrete hideout to sentimentalise about a pack of scrubby, smelly children on a beach scattered with bottle-tops and lolly-sticks and fringed by a sea thick with sun-oil and putrid with the main drains of Royale. He was here, he had chosen to be here, to spy. To spy on a woman.

The sun was getting lower. Already one could smell the September chill that all day had lain hidden beneath the heat. The cohorts of bathers were in quick retreat, striking their little camps and filtering up the steps and across the promenade into the shelter of the town where the lights were going up in the cafés. The announcer at the swimming pool harried his customers: ‘Allô! Allô! Fermeture en dix minutes! À dix-huit heures, fermeture de la piscine!’ Silhouetted in the path of the setting sun, the two Bombard rescue-boats with flags bearing a blue cross on a yellow background were speeding northwards for their distant shelter upriver in the Vieux Port. The last of the gay, giraffe-like sand-yachts fled down the distant waterline towards its corral among the sand dunes, and the three agents cyclistes in charge of the car parks pedalled away through the melting ranks of cars towards the police station in the centre of the town. In a matter of minutes the vast expanse of sand – the tide, still receding, was already a mile out – would be left to the seagulls that would soon be flocking in their hordes to forage for the scraps of food left by the picnickers. Then the orange ball of the sun would hiss down into the sea and the beach would, for a while, be entirely deserted, until, under cover of darkness, the prowling lovers would come to writhe briefly, grittily in the dark corners between the bathing-huts and the sea-wall.

On the beaten stretch of sand below where James Bond was sitting, two golden girls in exciting bikinis packed up the game of Jokari which they had been so provocatively playing, and raced each other up the steps towards Bond’s shelter. They flaunted their bodies at him, paused and chattered to see if he would respond, and, when he didn’t, linked arms and sauntered on towards the town, leaving Bond wondering why it was that French girls had more prominent navels than any others. Was it that French surgeons sought to add, even in this minute respect, to the future sex-appeal of girl babies?

And now, up and down the beach, the lifeguards gave a final blast on their horns to announce that they were going off duty, the music from the piscine stopped in mid-tune and the great expanse of sand was suddenly deserted.

But not quite! A hundred yards out, lying face downwards on a black and white striped bathing-wrap, on the private patch of firm sand where she had installed herself an hour before, the girl was still there, motionless, spreadeagled in direct line between James Bond and the setting sun that was now turning the left-behind pools and shallow rivulets into blood-red, meandering scrawls across the middle distance. Bond went on watching her – now, in the silence and emptiness, with an ounce more tension. He was waiting for her to do something – for something, he didn’t know what, to happen. It would be more true to say that he was watching over her. He had an instinct that she was in some sort of danger. Or was it just that there was the smell of danger in the air? He didn’t know. He only knew that he mustn’t leave her alone, particularly now that everyone else had gone.

James Bond was mistaken. Not everyone else had gone. Behind him, at the Café de la Plage on the other side of the promenade, two men in raincoats and dark caps sat at a secluded table bordering the sidewalk. They had half-empty cups of coffee in front of them and they didn’t talk. They sat and watched the blur on the frosted-glass partition of the shelter that was James Bond’s head and shoulders. They also watched, but less intently, the distant white blur on the sand that was the girl. Their stillness, and their unseasonable clothes, would have made a disquieting impression on anyone who, in his turn, might have been watching them. But there was no such person, except their waiter who had simply put them in the category of ‘bad news’ and hoped they would soon be on their way.

When the lower rim of the orange sun touched the sea, it was almost as if a signal had sounded for the girl. She slowly got to her feet, ran both hands backwards through her hair and began to walk evenly, purposefully towards the sun and the faraway froth of the waterline over a mile away. It would be violet dusk by the time she reached the sea and one might have guessed that this was probably the last day of her holiday, her last bathe.

James Bond thought otherwise. He left his shelter, ran down the steps to the sand and began walking out after her at a fast pace. Behind him, across the promenade, the two men in raincoats also seemed to think otherwise. One of them briskly threw down some coins and they both got up and, walking strictly in step, crossed the promenade to the sand and, with a kind of urgent military precision, marched rapidly side by side in Bond’s tracks.

Now the strange pattern of figures on the vast expanse of empty, blood-streaked sand was eerily conspicuous. Yet it was surely not one to be interfered with! The pattern had a nasty, a secret smell. The white girl, the bareheaded young man, the two squat, marching pursuers – it had something of a kind of deadly Grandmother’s Steps about it. In the café, the waiter collected the coins and looked after the distant figures, still outlined by the last quarter of the orange sun. It smelt like police business – or the other thing. He would keep it to himself but remember it. He might get his name in the papers.

James Bond was rapidly catching up with the girl. Now he knew that he would get to her just as she reached the waterline. He began to wonder what he would say to her, how he would put it. He couldn’t say, ‘I had a hunch you were going to commit suicide so I came after you to stop you.’ ‘I was going for a walk on the beach and I thought I recognised you. Will you have a drink after your swim?’ would be childish. He finally decided to say, ‘Oh, Tracy!’ and then, when she turned round, ‘I was worried about you.’ Which would at least be inoffensive and, for the matter of that, true.

The sea was now gunmetal below a primrose horizon. A small, westerly offshore breeze, drawing the hot land-air out to sea, had risen and was piling up wavelets that scrolled in whitely as far as the eye could see. Flocks of herring gulls lazily rose and settled again at the girl’s approach, and the air was full of their mewing and of the endless lap-lap of the small waves. The soft indigo dusk added a touch of melancholy to the empty solitude of sand and sea, now so far away from the comforting bright lights and holiday bustle of ‘La Reine de la Côte Opale’, as Royale-les-Eaux had splendidly christened herself. Bond looked forward to getting the girl back to those bright lights. He watched the lithe golden figure in the white one-piece bathing-suit and wondered how soon she would be able to hear his voice above the noise of the gulls and the sea. Her pace had slowed a fraction as she approached the waterline and her head, with its bell of heavy fair hair to the shoulders, was slightly bowed, in thought perhaps, or tiredness.

Bond quickened his step until he was only ten paces behind her. ‘Hey! Tracy!’

The girl didn’t start or turn quickly round. Her steps faltered and stopped, and then, as a small wave creamed in and died at her feet, she turned slowly and stood squarely facing him. Her eyes, puffed and wet with tears, looked past him. Then they met his. She said dully, ‘What is it? What do you want?’

‘I was worried about you. What are you doing out here? What’s the matter?’

The girl looked past him again. Her clenched right hand went up to her mouth. She said something, something Bond couldn’t understand, from behind it. Then a voice, from very close behind Bond, said softly, silkily, ‘Don’t move or you get it back of the knee.’

Bond swirled round into a crouch, his gun-hand inside his coat. The steady silver eyes of the two automatics sneered at him.

Bond slowly straightened himself. He dropped his hand to his side and the held breath came out between his teeth in a quiet hiss. The two deadpan, professional faces told him even more than the two silver eyes of the guns. They held no tension, no excitement. The thin half-smiles were relaxed, contented. The eyes were not even wary. They were almost bored. Bond had looked into such faces many times before. This was routine. These men were killers – pro killers.

Bond had no idea who these men were, who they worked for, what this was all about. On the theory that worry is a dividend paid to disaster before it is due, he consciously relaxed his muscles and emptied his mind of questions. He stood and waited.

‘Position your hands behind your neck.’ The silky, patient voice was from the South, from the Mediterranean. It fitted with the men’s faces – tough-skinned, widely pored, yellow-brown. Marseillais perhaps, or Italian. The Mafia? The faces belonged to good secret police or tough crooks. Bond’s mind ticked and whirred, selecting cards like an IBM machine. What enemies had he got in those areas? Might it be Blofeld? Had the hare turned upon the hound?

When the odds are hopeless, when all seems to be lost, then is the time to be calm, to make a show of authority – at least of indifference. Bond smiled into the eyes of the man who had spoken. ‘I don’t think your mother would like to know what you are doing this evening. You are a Catholic? So I will do as you ask.’ The man’s eyes glittered. Touché! Bond clasped his hands behind his head.

The man stood aside so as to have a clear field of fire while his Number Two removed Bond’s Walther PPK from the soft leather holster inside his trouser belt and ran expert hands down his sides, down his arms to the wrists and down the inside of his thighs. Then Number Two stood back, pocketed the Walther and again took out his own gun.

Bond glanced over his shoulder. The girl had said nothing, expressed neither surprise nor alarm. Now she was standing with her back to the group, looking out to sea, apparently relaxed, unconcerned. What in God’s name was it all about? Had she been used as a bait? But for whom? And now what? Was he to be executed, his body left lying to be rolled back inshore by the tide? It seemed the only solution. If it was a question of some kind of a deal, the four of them could not just walk back across the mile of sand to the town and say polite goodbyes on the promenade steps. No. This was the terminal point. Or was it? From the north, through the deep indigo dusk, came the fast, rattling hum of an outboard and, as Bond watched, the cream of a thick bow-wave showed and then the blunt outline of one of the Bombard rescue-craft, the flat-bottomed inflatable rubber boats with a single Thompson engine in the flattened stern. So they had been spotted! By the coastguards perhaps? And here was rescue! By God, he’d roast these two thugs when they got to the harbour police at the Vieux Port! But what story would he tell about the girl?

Bond turned back to face the men. At once he knew the worst. They had rolled their trousers up to the knees and were waiting, composedly, their shoes in one hand and their guns in the other. This was no rescue. It was just part of the ride. Oh well! Paying no attention to the men, Bond bent down, rolled up his trousers as they had done and, in the process of fumbling with his socks and shoes, palmed one of his heel knives and, half turning towards the boat that had now grounded in the shallows, transferred it to his right-hand trouser pocket.

No words were exchanged. The girl climbed aboard first, then Bond, and lastly the two men who helped the engine with a final shove on the stern. The boatman, who looked like any other French deep-sea fisherman, whirled the blunt nose of the Bombard round, changed gears to forward, and they were off northwards through the buffeting waves while the golden hair of the girl streamed back and softly whipped James Bond’s cheek.

‘Tracy. You’re going to catch cold. Here. Take my coat.’ Bond slipped his coat off. She held out a hand to help him put it on her. In the process her hand found his and pressed it. Now what the hell? Bond edged closer to her. He felt her body respond. Bond glanced at the two men. They sat hunched against the wind, their hands in their pockets, watchful, but somehow uninterested. Behind them the necklace of lights that was Royale receded swiftly until it was only a golden glow on the horizon. James Bond’s right hand felt for the comforting knife in his pocket and ran his thumb across the razor-sharp blade.

While he wondered how and when he might have a chance to use it, the rest of his mind ran back over the previous twenty-four hours and panned them for the gold-dust of truth.

2

Gran Turismo

Almost exactly twenty-four hours before, James Bond had been nursing his car, the old Continental Bentley – the ‘R’ type chassis with the big 6 engine and a 13:40 back-axle ratio – that he had now been driving for three years, along that fast but dull stretch of N1 between Abbeville and Montreuil that takes the English tourist back to his country via Silver City Airways from Le Touquet or by ferry from Boulogne or Calais. He was hurrying safely, at between eighty and ninety, driving by the automatic pilot that is built in to all rally-class drivers, and his mind was totally occupied with drafting his letter of resignation from the Secret Service.

The letter, addressed ‘Personal for M’, had got to the following stage:

Sir,

I have the honour to request that you will accept my resignation from the Service, effective forthwith.

My reasons for this submission, which I put forward with much regret, are the following:

(1) My duties in the Service, until some twelve months ago, have been connected with the Double O Section and you, sir, have been kind enough, from time to time, to express your satisfaction with my performance of those duties, which, I, for my part, have enjoyed. To my chagrin [Bond had been pleased with this fine word], however, on the successful completion of Operation ‘Thunderball’, I received personal instructions from you to concentrate all my efforts, without a terminal date [another felicitous phrase!], on the pursuit of Ernst Stavro Blofeld and on his apprehension, together with any members of SPECTRE – otherwise ‘The Special Executive for Counter-Intelligence, Revenge and Extortion’ – if that organisation had been re-created since its destruction at the climax of Operation ‘Thunderball’.

(2) I accepted the assignment with, if you will recall, reluctance. It seemed to me, and I so expressed myself at the time, that this was purely an investigatory matter which could well have been handled, using straightforward police methods, by other sections of the Service – local Stations, allied foreign secret services and Interpol. My objections were overruled, and for close on twelve months I have been engaged all over the world in routine detective work which, in the case of every scrap of rumour, every lead, has proved abortive. I have found no trace of this man nor of a revived SPECTRE, if such exists.

(3) My many appeals to be relieved of this wearisome and fruitless assignment, even when addressed to you personally, sir, have been ignored or, on occasion, curtly dismissed, and my frequent animadversions [another good one!] to the effect that Blofeld is dead have been treated with a courtesy that I can only describe as scant. [Neat, that! Perhaps a bit too neat!]

(4) The above unhappy circumstances have recently achieved their climax in my undercover mission (Ref. Station R’S PX 437/007) to Palermo, in pursuit of a hare of quite outrageous falsity. This animal took the shape of one ‘Blauenfelder’, a perfectly respectable German citizen engaged in viniculture – specifically the grafting of Moselle grapes onto the Sicilian strains to enhance the sugar content of the latter which, for your passing information [Steady on, old chap! Better redraft all this!], are inclined to sourness. My investigations into this individual brought me to the attention of the Mafia and my departure from Sicily was, to say the least, ignominious.

(5) Having regard, sir, to the above and, specifically, to the continued misuse of the qualities, modest though they may be, that have previously fitted me for the more arduous, and, to me, more rewarding, duties associated with the work of the Double O Section, I beg leave to submit my resignation from the Service.

I am, sir,

Your obedient servant,

007

Of course, reflected Bond, as he nursed the long bonnet of his car through a built-up S-bend, he would have to rewrite a lot of it. Some of it was a bit pompous and there were one or two cracks that would have to be ironed out or toned down. But that was the gist of what he would dictate to his secretary when he got back to the office the day after tomorrow. And if she burst into tears, to hell with her! He meant it. By God he did. He was fed to the teeth with chasing the ghost of Blofeld. And the same went for SPECTRE. The thing had been smashed. Even a man of Blofeld’s genius, in the impossible event that he still existed, could never get a machine of that calibre running again.

It was then, on a ten-mile straight cut through a forest, that it happened. Triple wind-horns screamed their banshee discord in his ear, and a low, white two-seater, a Lancia Flaminia Zagato Spyder with its hood down, tore past him, cut in cheekily across his bonnet and pulled away, the sexy boom of its twin exhausts echoing back from the border of trees. And it was a girl driving, a girl with a shocking-pink scarf tied round her hair, leaving a brief pink tail that the wind blew horizontal behind her.

If there was one thing that set James Bond really moving in life, with the exception of gun-play, it was being passed at speed by a pretty girl; and it was his experience that girls who drove competitively like that were always pretty – and exciting. The shock of the wind-horn’s scream had automatically cut out ‘George’, emptied Bond’s head of all other thought, and brought his car back under manual control. Now, with a tight-lipped smile, he stamped his foot into the floorboard, held the wheel firmly at a quarter to three, and went after her.

One hundred, one hundred and ten, one hundred and fifteen, and he still wasn’t gaining. Bond reached forward to the dashboard and flicked up a red switch. The thin high whine of machinery on the brink of torment tore at his eardrums and the Bentley gave an almost perceptible kick forward. One hundred and twenty, one hundred and twenty-five. He was definitely gaining. Fifty yards, forty, thirty! Now he could just see her eyes in her rear mirror. But the good road was running out. One of those exclamation marks that the French use to denote danger flashed by on his right. And now, over a rise, there was a church spire, the clustered houses of a small village at the bottom of a steepish hill, the snake sign of another S-bend. Both cars slowed down – ninety, eighty, seventy. Bond watched her tail lights briefly blaze, saw her right hand reach down to the floor stick, almost simultaneously with his own, and change down. Then they were in the S-bend, on cobbles, and he had to brake as he enviously watched the way her de Dion axle married her rear wheels to the rough going, while his own live axle hopped and skittered as he wrenched at the wheel. And then it was the end of the village, and, with a brief wag of her tail as she came out of the S, she was off like a bat out of hell up the long straight rise and he had lost fifty yards.

And so the race went on, Bond gaining a little on the straights but losing it all to the famous Lancia road-holding through the villages – and, he had to admit, to her wonderful, nerveless driving. And now a big Michelin sign said ‘Montreuil 5, Royale-les-Eaux 10, Le Touquet-Paris-Plage 15’, and he wondered about her destination and debated with himself whether he shouldn’t forget about Royale and the night he had promised himself at its famous casino and just follow where she went, wherever it was, and find out who this devil of a girl was.

The decision was taken out of his hands. Montreuil is a dangerous town with cobbled, twisting streets and much farm traffic. Bond was fifty yards behind her at the outskirts, but, with his big car, he couldn’t follow her fast slalom through the hazards and, by the time he was out of the town and over the Étaples–Paris level-crossing, she had vanished. The left-hand turn for Royale came up. Was there a little dust hanging in the bend? Bond took the turn, somehow knowing that he was going to see her again.

He leant forward and flicked down the red switch. The moan of the blower died away and there was silence in the car as he motored along, easing his tense muscles. He wondered if the supercharger had damaged the engine. Against the solemn warnings of Rolls-Royce, he had had fitted, by his pet expert at the Headquarters’ motor pool, an Arnott supercharger controlled by a magnetic clutch. Rolls-Royce had said the crankshaft bearings wouldn’t take the extra load and, when he confessed to them what he had done, they regretfully but firmly withdrew their guarantees and washed their hands of their bastardised child. This was the first time he had notched one hundred and twenty-five and the rev. counter had hovered dangerously over the red area at four and a half thousand. But the temperature and oil were OK and there were no expensive noises. And, by God, it had been fun!

James Bond idled through the pretty approaches to Royale, through the young beeches and the heavy-scented pines, looking forward to the evening and remembering his other annual pilgrimages to this place and, particularly, the great battle across the baize he had had with Le Chiffre so many years ago. He had come a long way since then, dodged many bullets and much death and loved many girls, but there had been a drama and a poignancy about that particular adventure that every year drew him back to Royale and its casino and to the small granite cross in the little churchyard that simply said, ‘Vesper Lynd. RIP.’

And now what was the place holding for him on this beautiful September evening? A big win? A painful loss? A beautiful girl – that beautiful girl?

To think first of the game. This was the weekend of the ‘clôture annuelle’. Tonight, this very Saturday night, the Casino Royale was holding its last night of the season. It was always a big event and there would be pilgrims even from Belgium and Holland, as well as the rich regulars from Paris and Lille. In addition, the Syndicat d’Initiative et des Bains de Mer de Royale traditionally threw open its doors to all its local contractors and suppliers, and there was free champagne and a great groaning buffet to reward the town people for their work during the season. It was a tremendous carouse that rarely finished before breakfast time. The tables would be packed and there would be a very high game indeed.

Bond had one million francs of private capital – Old Francs, of course – about eight hundred pounds’ worth. He always reckoned his private funds in Old Francs. It made him feel so rich. On the other hand, he made out his official expenses in New Francs because that made them look smaller – but probably not to the Chief Accountant at Headquarters! One million francs! For that evening he was a millionaire! Might he so remain by tomorrow morning!

And now he was coming into the Promenade des Anglais and there was the bastard Empire frontage of the Hôtel Splendide. And there, by God, on the gravel sweep alongside its steps, stood the little white Lancia, and at this moment a bagagiste, in a striped waistcoat and green apron, was carrying two Vuitton suitcases up the steps to the entrance!

So!

James Bond slid his car into the million-pound line of cars in the car park, told the same bagagiste, who was now taking rich, small stuff out of the Lancia, to bring up his bags, and went in to the reception desk. The manager impressively took over from the clerk and greeted Bond with golden-toothed effusion, while making a mental note to earn a good mark with the Chef de Police by reporting Bond’s arrival, so that the Chef could, in his turn, make a good mark with the Deuxième and the SDT by putting the news on the teleprinter to Paris.

Bond said, ‘By the way, Monsieur Maurice. Who is the lady who has just driven up in the white Lancia? She is staying here?’

‘Yes, indeed, mon Commandant.’ Bond received an extra two teeth in the enthusiastic smile. ‘The lady is a good friend of the house. The father is a very big industrialist from the South. She is la Comtesse Teresa di Vicenzo. Monsieur must surely have read of her in the papers. Madame la Comtesse is a lady – how shall I put it?’ – the smile became secret, between men – ‘a lady, shall we say, who lives life to the full.’

‘Ah, yes. Thank you. And how has the season been?’

The small talk continued as the manager personally took Bond up in the lift and showed him into one of the handsome grey and white Directoire rooms with the deep-rose coverlet on the bed that Bond remembered so well. Then, with a final exchange of courtesies, James Bond was alone.

Bond was faintly disappointed. She sounded a bit grand for him, and he didn’t happen to like girls, film stars for instance, who were in any way public property. He liked private girls, girls he could discover himself and make his own. Perhaps, he admitted, there was inverted snobbery in this. Perhaps, even less worthily, it was that the famous ones were less easy to get.

His two battered suitcases came and he unpacked leisurely and then ordered from Room Service a bottle of the Taittinger Blanc de Blancs that he had made his traditional drink at Royale. When the bottle, in its frosted silver bucket, came, he drank a quarter of it rather fast and then went into the bathroom and had an ice-cold shower and washed his hair with Pinaud Elixir, that prince among shampoos, to get the dust of the roads out of it. Then he slipped on his dark-blue tropical worsted trousers, white Sea Island cotton shirt, socks and black casual shoes (he abhorred shoelaces), and went and sat by the window and looked out across the promenade to the sea and wondered where he would have dinner and what he would choose to eat.

James Bond was not a gourmet. In England he lived on grilled soles, oeufs en cocotte and cold roast beef with potato salad. But when travelling abroad, generally by himself, meals were a welcome break in the day, something to look forward to, something to break the tension of fast driving, with its risks taken or avoided, the narrow squeaks, the permanent background of concern for the fitness of his machine. In fact, at this moment, after covering the long stretch from the Italian frontier at Ventimiglia in a comfortable three days (God knew there was no reason to hurry back to Headquarters!), he was fed to the teeth with the sucker-traps for gourmandising tourists. The ‘Hostelleries’, the ‘Vieilles Auberges’, the ‘Relais Fleuris’ – he had had the lot. He had had their ‘Bonnes Tables’, and their ‘Fines Bouteilles’. He had had their ‘Spécialités du Chef’ – generally a rich sauce of cream and wine and a few button mushrooms concealing poor-quality meat or fish. He had had the whole lip-smacking ritual of winemanship and foodmanship and, incidentally, he had had quite enough of the Bisodol that went with it!

The French belly-religion had delivered its final kick at him the night before. Wishing to avoid Orléans, he had stopped south of this uninspiring city and had chosen a mock-Breton auberge on the south bank of the Loire, despite its profusion of window-boxes and sham beams, ignoring the china cat pursuing the china bird across its gabled roof, because it was right on the edge of the Loire – perhaps Bond’s favourite river in the world. He had stoically accepted the hammered copper warming pans, brass cooking utensils and other antique bogosities that cluttered the walls of the entrance hall, had left his bag in his room and had gone for an agreeable walk along the softly running, swallow-skimmed river. The dining-room, in which he was one of a small handful of tourists, had sounded the alarm. Above a fireplace of electric logs and over-polished fire-irons there had hung a coloured plaster escutcheon bearing the dread device: ICY DOULCE FRANCE. All the plates, of some hideous local ware, bore the jingle, irritatingly inscrutable, ‘Jamais en vain, toujours en vin’, and the surly waiter, stale with ‘fin de saison’, had served him with the fly-walk of the pâté maison (sent back for a new slice) and a poularde à la crème that was the only genuine antique in the place. Bond had moodily washed down this sleazy provender with a bottle of instant Pouilly-Fuissé and was finally insulted the next morning by a bill for the meal in excess of five pounds.

It was to efface all these dyspeptic memories that Bond now sat at his window, sipped his Taittinger and weighed up the pros and cons of the local eating places and wondered what dishes it would be best to gamble on. He finally chose one of his favourite restaurants in France, a modest establishment, unpromisingly placed exactly opposite the railway station of Étaples, rang up his old friend Monsieur Bécaud for a table and, two hours later, was motoring back to the Casino with turbot poché, sauce mousseline, and half the best roast partridge he had eaten in his life, under his belt.

Greatly encouraged, and further stimulated by half a bottle of Mouton Rothschild ’53 and a glass of ten-year-old Calvados with his three cups of coffee, he went cheerfully up the thronged steps of the Casino with the absolute certitude that this was going to be a night to remember.

3

The Gambit of Shame

(The Bombard had now beaten round the dolefully clanging bell-buoy and was hammering slowly up the River Royale against the current. The gay lights of the little marina, haven of cross-Channel yachtsmen, showed way up on the right bank, and it crossed Bond’s mind to wait until they were slightly above it and then plunge his knife into the side and bottom of the rubber Bombard and swim for it. But he already heard in his mind the boom of the guns and heard the zwip and splash of the bullets round his head until, probably, there came the bright burst of light and the final flash of knowledge that he had at last had it. And anyway, how well could the girl swim, and in this current? Bond was now very cold. He leant closer against her and went back to remembering the night before and combing his memories for clues.)

After the long walk across the Salle d’Entrée, past the vitrines of Van Cleef, Lanvin, Hermès and the rest, there came the brief pause for identification at the long desk backed by the tiers of filing cabinets, the payment for the Carte d’Entrée pour les Salles de Jeux, the quick, comptometer survey of the physiognomiste at the entrance, the bow and flourish of the garishly uniformed huissier at the door, and James Bond was inside the belly of the handsome, scented machine.

He paused for a moment by the caisse, his nostrils flaring at the smell of the crowded, electric, elegant scene, then he walked slowly across to the top chemin-de-fer table beside the entrance to the luxuriously appointed bar, and caught the eye of Monsieur Pol, the Chef de Jeu of the high game. Monsieur Pol spoke to a huissier and Bond was shown to Number 7, reserved by a counter from the huissier’s pocket. The huissier gave a quick brush to the baize inside the line – that famous line that had been the bone of contention in the Tranby Croft case involving King Edward VII – polished an ashtray and pulled out the chair for Bond. Bond sat down. The shoe was at the other end of the table, at Number 3. Cheerful and relaxed, Bond examined the faces of the other players while the Changeur changed his notes for a hundred thousand into ten blood-red counters of ten thousand each. Bond stacked them in a neat pile in front of him and watched the play which, he saw from the notice hanging between the green-shaded lights over the table, was for a minimum of one hundred New Francs, or ten thousand of the old. But he noted that the game was being opened by each banker for up to five hundred New Francs – serious money – say forty pounds as a starter.

The players were the usual international mixture – three Lille textile tycoons in over-padded dinner-jackets, a couple of heavy women in diamonds who might be Belgian, a rather Agatha Christie-style little Englishwoman who played quietly and successfully and might be a villa owner, two middle-aged Americans in dark suits who appeared cheerful and slightly drunk, probably down from Paris, and Bond. Watchers and casual punters were two-deep round the table. No girl!

The game was cold. The shoe went slowly round the table, each banker in turn going down on that dread third coup which, for some reason, is the sound barrier at chemin-de-fer which must be broken if you are to have a run. Each time, when it came to Bond’s turn, he debated whether to bow to the pattern and pass his bank after the second coup. Each time, for nearly an hour of play, he obstinately told himself that the pattern would break, and why not with him? That the cards have no memory and that it was time for them to run. And each time, as did the other players, he went down on the third coup. The shoe came to an end. Bond left his money on the table and wandered off among the other tables, visiting the roulette, the trente-et-quarante and the baccarat table, to see if he could find the girl. When she had passed him that evening in the Lancia, he had only caught a glimpse of fair hair and of a pure, rather authoritative profile. But he knew that he would recognise her at once, if only by the cord of animal magnetism that had bound them together during the race. But there was no sign of her.

Bond went back to the table. The croupier was marshalling the eight packs into the oblong block that would soon be slipped into the waiting shoe. Since Bond was beside him, the croupier offered him the neutral, plain red card to cut the pack with. Bond rubbed the card between his fingers and, with amused deliberation, slipped it as nearly halfway down the block of cards as he could estimate. The croupier smiled at him and at his deliberation, went through the legerdemain that would in due course bring the red stop card into the tongue of the shoe and stop the game just six cards before the end of the shoe, packed the long block of cards into the shoe, slid in the metal tongue that held them prisoner and announced, loud and clear: ‘Messieurs [the ‘mesdames’ are traditionally not mentioned; since Victorian days it has been assumed that ladies do not gamble], les jeux sont faits. Numéro six à la main.’ The Chef de Jeu, on his throne behind the croupier, took up the cry, the huissiers shepherded distant stragglers back to their places, and the game began again.

James Bond confidently bancoed the Lille tycoon on his left, won, made up the cagnotte with a few small counters, and doubled the stake to two thousand New Francs – two hundred thousand of the old.

He won that, and the next. Now for the hurdle of the third coup and he was off to the races! He won it with a natural nine! Eight hundred thousand in the bank (as Bond reckoned it)! Again he won, with difficulty this time – his six against a five. Then he decided to play it safe and pile up some capital. Of the one million six, he asked for the six hundred to be put ‘en garage’, removed from the stake, leaving a bank of one million. Again he won. Now he put a million ‘en garage’. Once more a bank of a million, and now he would have a fat cushion of one million six coming to him anyway! But it was getting difficult to make up his stake. The table was becoming wary of this dark Englishman who played so quietly, wary of the half-smile of certitude on his rather cruel mouth. Who was he? Where did he come from? What did he do? There was a murmur of excited speculation round the table. So far a run of six. Would the Englishman pocket his small fortune and pass the bank? Or would he continue to run it? Surely the cards must change! But James Bond’s mind was made up. The cards have no memory in defeat. They also have no memory in victory. He ran the bank three more times, adding each time a million to his ‘garage’, and then the little old English lady, who had so far left the running to the others, stepped in and bancoed him at the tenth turn, and Bond smiled across at her, knowing that she was going to win. And she did, ignominiously, with a one against Bond’s ‘bûche’ – two kings, making zero.

There was a sigh of relief round the table. The spell had been broken! And a whisper of envy as the heavy, mother-of-pearl plaques piled nearly a foot high, four million six hundred thousand francs’ worth, well over three thousand pounds, were shunted across to Bond with the flat of the croupier’s spatula. Bond tossed a plaque for a thousand New Francs to the croupier, received the traditional ‘Merci, monsieur! Pour le personnel!’ and the game went on.

James Bond lit a cigarette and paid little attention as the shoe went shunting round the table away from him. He had made a packet, dammit! A bloody packet! Now he must be careful. Sit on it. But not too careful, not sit on all of it! This was a glorious evening. It was barely past midnight. He didn’t want to go home yet. So be it! He would run his bank when it came to him, but do no bancoing of the others – absolutely none. The cards had got hot. His run had shown that. There would be other runs now, and he could easily burn his fingers chasing them.

Bond was right. When the shoe got to Number 5, to one of the Lille tycoons two places to the left of Bond, an ill-mannered, loud-mouthed player who smoked a cigar out of an amber-and-gold holder and who tore at the cards with heavily manicured, spatulate fingers and slapped them down like a German tarot player, he quickly got through the third coup and was off. Bond, in accordance with his plan, left him severely alone and now, at the sixth coup, the bank stood at two hundred thousand New Francs – two million of the old, and the table had got wary again. Everyone was sitting on his money.

The croupier and the Chef de Jeu made their loud calls, ‘Un banco de deux cent mille! Faites vos jeux, messieurs. Il reste à compléter! Un banco de deux cent mille!’

And then there she was! She had come from nowhere and was standing beside the croupier, and Bond had no time to take in more than golden arms, a beautiful golden face with brilliant blue eyes and shocking-pink lips, some kind of a plain white dress, a bell of golden hair down to her shoulders, and then it came. ‘Banco!’

Everyone looked at her and there was a moment’s silence. And then ‘Le banco est fait’ from the croupier, and the monster from Lille (as Bond now saw him) was tearing the cards out of the shoe, and hers were on their way over to her on the croupier’s spatula.

She bent down and there was a moment of discreet cleavage in the white V of her neckline.

‘Une carte.’

Bond’s heart sank. She certainly hadn’t anything better than a five. The monster turned his up. Seven. And now he scrabbled out a card for her and flicked it contemptuously across. A simpering queen!

The croupier delicately faced her other two cards with the tip of his spatula. A four! She had lost!

Bond groaned inwardly and looked across to see how she had taken it.

What he saw was not reassuring. The girl was whispering urgently to the Chef de Jeu. He was shaking his head, sweat was beading on his cheeks. In the silence that had fallen round the table, the silence that licks its lips at the strong smell of scandal, which was now electric in the air, Bond heard the Chef de Jeu say firmly, ‘Mais c’est impossible. Je regrette, madame. Il faut vous arranger à la caisse.’

And now that most awful of all whispers in a casino was running among the watchers and the players like a slithering reptile: ‘Le coup du déshonneur! C’est le coup du déshonneur! Quelle honte! Quelle honte!’

Oh, my God! thought Bond. She’s done it! She hasn’t got the money! And for some reason she can’t get any credit at the caisse!

The monster from Lille was making the most of the situation. He knew that the Casino would pay in the case of a default. He sat back with lowered eyes, puffing at his cigar, the injured party.

But Bond knew of the stigma the girl would carry for the rest of her life. The casinos of France are a strong trade union. They have to be. Tomorrow the telegrams would go out: ‘Madame la Comtesse Teresa di Vicenzo, passport number X, is to be put on the black list.’ That would be the end of her casino life in France, in Italy, probably also in Germany, Egypt and, today, England. It was like being declared a bad risk at Lloyd’s or with the City security firm of Dun & Bradstreet. In American gambling circles, she might even have been liquidated. In Europe, for her, the fate would be almost as severe. In the circles in which, presumably, she moved, she would be bad news, unclean. The ‘coup du déshonneur’ simply wasn’t done. It was social ostracism.

Not caring about the social ostracism, thinking only about the wonderful girl who had outdriven him, shown him her tail, between Abbeville and Montreuil, James Bond leant slightly forward. He tossed two of the precious pearly plaques into the centre of the table. He said, with a slightly bored, slightly puzzled intonation, ‘Forgive me. Madame has forgotten that we agreed to