Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

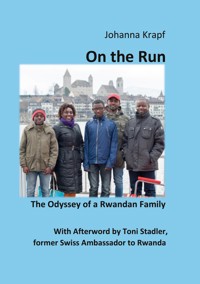

The true story of Joséphine Niyikiza and Désiré Nsanzineza is a tale of flight, exile and integration beginning with the outbreak of civil war in Rwanda. What follows is an Odyssey through central Africa, in which time they start a family. Separated in a raid on their home, they lose touch for years until they are at last reunited in Switzerland, where they face many challenges before integration is successful.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 238

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SYNOPSIS

This is a true story

Two young people, Désiré and Joséphine, growing up happily in secure loving families and making plans for their future careers, are suddenly torn violently out of their peaceful everyday lives as civil war destroys everything they ever cared about. They flee from their homes in Rwanda, Africa, to neighbouring Congo-Kinshasa. They survive in desperate conditions in refugee camps, are forced to flee again and spend months wandering through the jungle where they encounter all kinds of danger from wild animals, pygmies, pursuing armed forces, and even nature itself, until they again reach safety, this time in Congo-Brazzaville. They settle down and have two sons. Although they manage to build a new life for themselves, they are homesick for Rwanda and so in 2000, six years after the civil war, decide to return. This is a disastrous decision. Désiré is arrested, jailed and tortured but manages to escape and get back to his family. They find themselves fleeing again, to Cameroon, where they are attacked and the family is split up. All alone with her third son, still a baby, in 2004 Joséphine is taken to Switzerland where she applies for asylum. After a long battle, this is granted but she has no idea what has happened to her husband and two older sons. Fortunately, the Red Cross succeeds in tracing the two boys and after yet another battle they are admitted to Switzerland to join their mother and little brother in 2006. Although she has no news of her husband, she never gives up the search for him and remains convinced he is still alive. Meanwhile, Désiré has been close to death from sickness and disease, enslaved in Chad, escaped, and finally arrived in Nigeria. Here he tries to search for his lost family and finally discovers that they are all together in Switzerland. 9 years after the family was split up, Désiré is finally allowed to enter Switzerland and be reunited with his wife and three sons. Throughout these harrowing experiences, Désiré and Joséphine never lose faith in God, constantly give thanks and recognise His hand over their lives.

Contents

Foreword

by Joséphine Niyikiza and Désiré Nsanzineza

Prologue

: Arrival

PART I: Africa

I. Rwanda

II. Congo-Kinshasa

III. Congo-Brazzaville

IV. Separation

PART II: Switzerland

I. Asylum

II. Rapperswil-Jona

III. Africa

IV. Together Again

V. Settling In

Epilogue

Author’s Remarks

Interview with Nicole Windlin

Chronology

Their Journeys

A Brief History of Rwanda

Rwanda 1994 – Civil War and Genocide

Afterword by Toni Stadler

Bibliography

Foreword

May our story serve as a bridge linking Africa and Europe, Rwanda and Switzerland, our difficult past with a hopeful future – and may it connect our readers with the many refugees living in Switzerland.

For a long time, we – Joséphine Niyikiza and Désiré Nsanzineza – have cherished the wish to share the story of our flight in book form. Again and again, we have been asked to tell our story, both privately and publicly, and once we start there is never time to satisfy the curiosity of our audience. Only a book could provide an overview of our convoluted journey as we fled through Africa, of the events surrounding the separation of our family, and our reunion in Switzerland in January 2013.

In addition, we want to express our gratitude that, with God’s help, we have all survived and can face the future with optimism.

But how should we undertake such a project, how could we ever publish a book? That’s much too expensive, we were told, and we certainly didn’t have the time in addition to all our other duties. We needed someone who could write our story down for us. We didn’t let that deter us. One day, our dream would come true, we were sure. And indeed, just before our wedding in Rapperswil-Jona in the spring of 2014 a friend told us he had found an author who was interested in working with us. Soon after this we met Johanna Krapf. We clicked immediately and in autumn 2014 we set off together on the Book Adventure.

Many people, institutions and organisations have contributed to the production of this book. Some encouraged us to believe in our dream, others gave us their time, others supported us financially. We thank them all most warmly from the bottom of our hearts.

In particular, we would like to mention:

Johanna Krapf, who listened to us for hours and hours on end, and wrote down our story;

All those who supported us on the Crowdfunding platform. Especially the church in Prisma and the KJS association;

The Swiss Red Cross;

The city of Rapperswil-Jona;

The Protestant Reformed Church of the Canton of St Gallen

The Protestant Reformed Church of Rapperswil-Jona

Our story tells of the monstrosities of the wars raging in Africa, of our wanderings, our trials and tribulations on the run, but it also reflects our faith in God, our gratitude to Him and countless kind people, and our future hopes for our life in Switzerland.

Joséphine Niyikiza and Désiré Nsanzineza, January 2016

PROLOGUE

ARRIVAL 2004

After the plane lands, I follow the Missionary into the airport building.

“Wait here while I get my car,” he says, shoving a bundle of papers into my hand,

I sit down, clutching my baby to me, and wait.

All around me, people are dashing about. I’m too tired to take much notice, but everything seems so frantic here. Where am I? How long have I been waiting? Why hasn’t the Missionary come back yet?

“WAH-wah-wah-WAH-wah …?”

A man in uniform, a language I’ve never heard before. Where am I?

“Excusez-moi?”

“Que faites-vous là?”

He has a strange accent in his French, and he is white. I explain that I’m waiting for someone and he asks to see my papers. He has that self-important air that comes from wearing a uniform.

I’m too tired to argue and hand the bundle of papers over to him. He glances through them, and looks at me, looks at my baby.

“Who’s the baby’s father? Is that the person you’re waiting for?”

“No, my baby’s father isn’t white.”

“But your baby is mixed race?”

“No, he’s black.” I cuddle my sleeping child, my beautiful little boy. African babies are often paler skinned at birth and for the first few months, but my baby Espoir is not mixed race, he’s definitely black.

The man stares at us, unsmiling, suspicious. Then he shrugs, beckons and says, “Come with me.”

It’s a long way, and I see more people milling around, people from all over the world. Where am I? Is this still Africa? I’m so tired, too tired to think, too tired to feel any emotions, no fear, no surprise, just numb perplexity. What is this big house that I am in now?

“Follow me!” I follow.

“You have to register. What’s your name?” This is a different person, not in uniform.

“Joséphine Niyikiza.”

Niyikiza means God is my saviour; it’s the name my parents chose for me after I was born, a special name, unique to me, a gift from my parents and a source from which I can draw strength all my life.

Where is the Missionary who brought me here? I have no idea who he is nor why he helped me, and I didn’t get the chance to thank him. That bothers me. I want to say thank you to him for saving my life but I have no idea how to contact him, and can’t describe him. Young or old – I don’t know. All white people look alike to me.

Does he know where they have brought me? Is he looking for me? Or are all these people his guests, his employees, his congregation, and he has to take care of them? Everything is so strange and different here.

A woman is smiling at me, speaking that wah-wah language that I don’t understand. Espoir has woken and is crying, his clothes soaking wet. The woman is kind, her voice is gentle as she takes Espoir from me and undresses him. Then she puts him into a gleaming white tub and washes him in the warm sudsy water. Espoir stops crying and chuckles with pleasure, waving his sturdy little arms and legs, splashing in the water and enjoying getting clean. Another woman asks me in French if I have a change of clothes for him. No, I have nothing, nothing for him and nothing for me, no luggage at all.

“Come with me,” she says and as I hesitate to leave my baby with a stranger she adds, “Don’t worry, he’s in good hands.

We’ll just get him some clean clothes to wear.”

As we return with the fresh things, I can hear him laughing and gurgling from the other side of the room. That, at least, is a good thing. We dry him and I dress him in the nice clean clothes.

“Where are you from?” An African man, speaking a language I understand.

“Rwanda.”

“Aha! Hutu or Tutsi?”

“I’m Rwandan.”

“Yes, OK, but Hutu or Tutsi?” He tells me he has heard about the genocide in Rwanda, everyone in the world has heard about its horrors, and he persists with his questions.

“Come on, what are you? Hutu or Tutsi? Which side are you on?”

“You know what?” I tell him firmly. “Leave me in peace. I’m Rwandan.”

By this time I’m getting hungry. I have been given a food voucher so I decide to use it and get something to eat. However, the counter where the other people got their food is now closed. “That’s funny,” I think. “It’s still light, it can’t be so late.” I look around, and see there are clocks everywhere. And they all show the same time: 21:30, half past nine in the evening. Are they all wrong? At half past nine, it should be dark.

I go back to the place where the refugees are, and ask the African how come I can’t get anything to eat now.

“It’s late,” he replies. “We aren’t in Africa here, you know.”

I am thunderstruck. Really, not in Africa? But if not in Africa, where am I? And where is my husband Désiré and my two little boys? I try not to show my shock and just murmur, “Okay.”

The African is still speaking. “And one more thing, when they are interviewing you and ask where you are from, whatever you do don’t tell them you are from Rwanda.“

“But I’ve already been interviewed.”

He laughs, more a sneer than a laugh. “You really don’t have a clue, do you? You can’t tell the time, you think you’re still in Africa, and you think you’ve been interviewed. Hah, you’ll soon find out what it means to be interviewed! Just wait and see what a real interview is!”

“What is it then?”

“It’s an interrogation. You have to tell them exactly where you are from, why you fled and so forth and so on. But watch out. If you’re from Rwanda, you must never, ever, tell them your real story, because they don’t like your lot here. They won’t let people from Rwanda in. They’re afraid of you, all you Hutus and Tutsis murdering one another, you might start another genocide here.”

“Afraid? Of me?”

“Sure. If they find out you’re Rwandan you’ll be back in Africa in a flash.”

Back to Africa? Back to Cameroon, back to Bukavu, Congo-Kinshasa? My mind is still numb but my blood runs cold at the thought.

How should I act at the interview? “The truth will out,” was what my mother had always told me. “Liar, liar, pants on fire!”

But the African had warned me that people from Rwanda aren’t welcome here. That night I can’t sleep in spite of my exhaustion, tossing to and fro, trying to decide what to say.

Images from my past keep flashing before my eyes: does that put me in a bad light? Finally, I decide to tell a partial truth. Yes, I’m Rwandan, but I won’t tell them the true story of my flight and how I got here. Finally, I fall asleep with a prayer on my lips: “God, stay by me as You have always done up to now.”

PART 1 AFRICA

I RWANDA

Joséphine’s Story 1980 - 1996

“Joséphine!” “Oui, maman, j’arrive!” Dragging my little sister along I hurtled down the hill towards our farmstead with its neat buildings arranged around a central yard. When Maman called, we obeyed, and in any case, after running around outside with the animals for so long we were ready for the delicious meal she was about to place before us.

My father was already seated when we reached the house, so we hurriedly splashed our hands and faces with cold water to clean them, and joined the rest of the family around the big table. Besides my father, mother, sister and me there were also three other youngsters who lived with us. They helped on the farm, in the fields and with the animals, with washing, cooking and cleaning, and they sat down to eat with us at mealtimes, lived with us and shared our lives. I thought of them as my siblings, and my parents made no distinction between us and them, but in fact we weren’t really related.

“Everyone is equal,” my parents insisted. That’s why it was so important for my sister and me not to appear different in any way from the other children in our village. On Sundays, for instance, we had to go to Church barefoot like them, although we could have afforded shoes.

I have no photos from my childhood. None of my mother, of my father or my seven siblings, none of myself or of our home – but deep inside I carry the picture of my extremely happy and carefree childhood in Rwanda. I see our large farmstead that my father had had built, nestling comfortably in the beautiful gently rolling hills.

I was born on 5 May 1980, the seventh child. My older siblings had all left home and some already had families of their own. I rarely saw them, apart from an older brother who lived nearby and came over to see us regularly. I loved him dearly, and admired him immensely. He was fun and played with us children, and also took the time to answer our questions. To me he seemed to know everything. I wasn’t the only one proud of him; my parents were, too, and he was well respected in the area.

My family home was in Western Rwanda, in a settlement consisting of many houses, a church, a primary school, a vocational college, a bank and a health centre. Our farm was made up of several buildings. Around a central courtyard were grouped a spacious house, a large kitchen wing, an annex, a laundry room and a barn. The family lived in the house and I had a room all to myself. The kitchen wing comprised several rooms and of course the kitchen itself, with a log fire. The annex was where we held parties. A rainwater collection system supplied water for the laundry and shower, and the barn housed the smaller animals – chickens, goats, rabbits and sheep. Beside and beyond these central buildings were the cowsheds and pens for the countless cows, fields and meadows, eucalyptus and cedar groves, and a vegetable garden lovingly tended by my mother, full of meticulously planted rows of aubergines and many other kinds of vegetables.

Yes, our farm was quite large, and I think it included the hill behind the house and the land right down to the valley floor. There were banana plantations, and fields of maize, manioc, sweet potatoes, yam roots, potatoes and soybeans – far more than we could eat ourselves, so we always shared our harvest with other families in the region to make sure nothing went to waste. Our farm was managed by an uncle, one of my father’s brothers, who was responsible for planting schedules, harvest management, tenants who cultivated small parcels of our land, and the day labourers. I don’t really know how the farm and plantations were run, I was so young and it didn’t interest me. My life revolved around my family and friends, the people I met every day, and what mattered was knowing that we were all happy.

Everything on our farm ran like clockwork. I was a child like all the others, working and playing just as they did. In the school vacations, each of us had a plot of land to cultivate, to dig, plant – maybe maize - and harvest. We village children organised ourselves and worked together on our plots, first on yours, then on hers, then on mine, and it was fun. Child labour? No way! It was taken for granted that we all helped one another, and we had no objection. During term time, however, I only had a few chores to do: washing up, watering the garden, helping prepare meals, taking fruit to the neighbours, and fetching water from the spring – on my head, of course.

I started school in 1985, at just five years old. That was young but I suppose they turned a blind eye, since my father himself taught in an elementary school. I think it was the right decision, though, because I was soon terribly bored and didn’t want to go to school any more. They let me try out the next class up, and I liked that much better so after some discussion I was allowed to stay. My new classmates were pleased, too, hoping I would help them with their homework and tests as I had done in the first class. There was no question of envy or resentment, every child wanted to do well and learn as much as possible, and attending school was a privilege that not every family could afford.

On the whole, I liked school. I was interested in everything, except drawing. I have no artistic talent but my first-grade teacher’s comment: ”Yuck, that’s terrible!” wasn’t very nice and killed any motivation I might have had. From that moment on I only drew when I absolutely couldn’t avoid it.

After finishing six grades in four years (I skipped another class) I had completed elementary school. The number of years had been raised to eight, and then gradually reduced back to six, so I was nine when I finished. That matched the nickname the other kids had given me: Rocket or “Iryumwotsi” in Kinyarwanda, because I was always dashing about. I did every task I was given straight away, and at express speed. My parents called me Phina, and in school I was Josée.

It went without saying that after elementary school I would continue my education, and so I went to the teacher’s seminary. That didn’t really suit me, because I didn’t see myself as a potential teacher. Keeping forty to sixty children in check, constantly trying to keep order, and earning very little – that didn’t appeal to me and I would never have chosen this career. In Rwanda, however, the children were assigned to a particular branch of study according to their examination results and the needs of the economy, and they themselves had no choice in the matter. All the same, I did what I could and after two years I was allowed to apply for a change of direction.

My parents supported me and perhaps my brother also had some influence behind the scenes, for my application was approved and I was allowed to go to a boarding school where I took foundation courses in law at the School for Administration and Law. I was never able to complete this training, because war broke out and I had to flee. But at the time, I wasn’t at all worried about the political situation. I was still a child, carefree and eager to learn, and absorbing all the knowledge I could in civics, legal studies, chemistry, physics, philosophy and French (incidentally, for the last six months before the war, Désiré was my French teacher). Almost everything interested me except history and geography, which bored me so much that I sometimes caught up on my lack of sleep in these classes. I often studied at night instead of sleeping because I was afraid of being kicked out of school and having to go home a failure. I could only do this in secret, for instance on the toilet, because there were very strict hours prescribed for sleep.

There were two dormitories, one for girls and one for boys, but classes were mixed and we also ate our meals together. I had a lot of friends, girls and boys. I’m not the sort to have just one best friend. I share this interest with one, and that interest with another, but whenever I am friends with a person I always give them my full attention. Generally, I get along well with most people. That was so in my youth, and I haven’t changed. That’s also why I was able to build a large circle of friends relatively quickly when I arrived as a refugee in Switzerland.

Back to boarding school. The two and a half years I spent there, up to the outbreak of war, were a really very pleasant time. I still felt very close to my family, partly because my brother, who was twelve years older than me, visited me every week. The girls used to flock around him and the boys admired him, not only because he was good-looking and brought much sought after sweets and soft drinks, but also because he took an interest in us.

As the end of my studies at this school approached, I started to think about what I would like to study at University: medicine maybe, or psychology? Philosophy interested me, too. The financial burden of my studies was never discussed. For my father a good education took top priority, and he often talked to me about how I had to be fully committed. Sometimes, I almost couldn’t listen to him any more. Of course I knew how important it was. And anyway, I myself wanted nothing else but to be able to study.

Naturally, my mother was also very supportive, but in our conversations she always stressed other aspects that were important in life.

“We humans are like flowers: in the night, when it’s dark, we rest, but when the sun warms us we open ourselves up to its rays. Yet we have no influence over its path. Nobody knows what tomorrow will bring. The future isn’t in our hands. Everything might suddenly change. That’s why you always have to do your best today. Only the present is sure for us humans. And don’t forget: we are really only guests on this earth. Our true home is in Heaven. That’s why I want to leave you with something important, a key that will open the door to Heaven for you. This key is prayer. You must never lose it.”

Yes, my mother often spoke to me in this way, but I wasn’t always receptive to her words. Sometimes, to be honest, she got on my nerves with her preaching. Stop that, Maman, I thought to myself, please don’t go on and on! Why should I care about the present? I want to think about my future, I want to study. I want to be grown up and make my own decisions. However, I would never have spoken these thoughts out loud, for in Rwanda children aren’t (or at least, at that time weren’t) in the habit of discussing anything with their parents and would definitely never contradict them.

Yet now, when I remember these conversations and look back to the outbreak of war, to the years spent trying to escape and my time in foreign countries, it was precisely these words of my mother that stayed with me day after day and gave me the strength to pick myself up when I was down. This is her legacy to me, and it’s a holy one. Prayer is the source of life for me.

Maman wasn’t always so serious. She often laughed with us and told us stories, especially in the evening. She was very fond of the riddles that are so popular in Rwanda. For instance: I have many children. When they fall down, they can’t come back to me (A branch and its leaves). Or: I am dark and what I give is white (a cow and its milk).

My mother always had a ready ear for other people’s problems, and would take the time to listen to them and talk to them, whether on a Sunday when she went to church, or on a weekday when someone needed her. Her sensitivity, empathy, and willingness to help made a great impression on me and together with my father’s generosity, kindness and love inspired my life’s dreams: I wanted to study so that I could have all the knowledge and money necessary to help people in distress. I wanted to help as many poor people as possible to escape from the vicious circle of poverty – no money, no education, no job, no money. Perhaps one day I would buy some land and build houses on it for peasants who had nothing. If that should bring in any cash, I would start a charity to help street children or widows. I also dreamed of marrying a man from a penniless family, just as my father had married my mother, a woman from very poor circumstances. Of course, it all turned out differently. War broke out and I had to flee. And when I finally got married, I was a refugee and had nothing more valuable to offer Désiré than what he offered me: love.

****

It was 1994, the vacation. As usual, I spent a few weeks with my family helping on the farm and in the house. Physical work did me good, instead of sitting studying all the time, and I enjoyed being with my parents very much. There was a strange atmosphere in the village, though, because these refugees from the north kept arriving, different people all the time, who settled down on the square in front of the school and cooked their food over campfires. They didn’t even have proper cooking utensils, and cooked their food in cans! Sometimes I just couldn’t resist going and peeping at them, wondering about their strange habits and their destitute state.

Naturally, we locals supported them and brought them sweet potatoes and manioc, but I never spent time talking to them so I didn’t know where they had come from nor why they were living on the street. Anyway, as I already said, I wasn’t particularly interested in history, geography or politics. I had no clue about the social tensions that had been building up for decades in Rwanda over the question of who belonged to the Tutsi minority or the Hutu majority, which social groups had suffered under which others, or why. Nobody at home was interested in discussing these conflicts.

I was and am a Rwandan.

When war broke out I was fourteen, a teenager with the world at my feet. I dreamed of studying at the University and looked forward to a carefree future. But that remained a dream.

On the eve of my return to boarding school I went to church where I met my friends and sang in the choir. As we were leaving, one of the girls said to me:

“You know what? Today is the last time I’ll see you.”

“Why do you say that?” I asked.

She shrugged. “I just believe that we won’t see each other again.”

Well, I wondered, was she joking? Or is it because I’m leaving in the morning to go back to school? I didn’t think it was funny.

“Okay,” I said and we hugged goodbye.

Next morning, my brother was going to pick me up. My bag was packed, my ID safely put away, everything ready for the journey. As always on my last evening, I went to bed with mixed feelings, a bit sad at saying goodbye to my family but also looking forward to seeing my school friends again.

Suddenly, I’m awake. Screams in the dark. I’m very cold. Everywhere men with machetes, massacring people. Run, run! I flee, without my bag, without my ID. Away from the knives, the blood, from the screaming. Alone, in my pyjamas. My brother hasn’t come. Frightened animals charge through the village. People dash here, there, aimlessly. Get away from here. Far away! Time stands still, I am numb, feeling nothing, understanding nothing, unable to think, like a broken-off branch swept away in the torrent of an unfettled stream of fleeing people. Away, anywhere, but away from here!

Sometimes I was caught up in the turbulent rapids when the soldiers of the Interahamwe1