0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Full Well Ventures

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

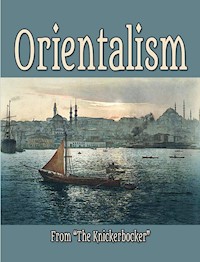

This article, "Orientalism," from the June 1853 issue of The Knickerbocker magazine, is an indepth discussion of the impact of Western civilization and technological innovation on areas of the Orient previously resistant to change.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Orientalism

© 2020 Full Well Ventures

Originally published in June 1853 issue of “The Knickerbocker” magazine

On the Cover: The Harbor of Constantinople pictured in 1890 from the Library of Congress.

KNICKERBOCKER

Orientalism

STRICTLY SPEAKING, Orientalism is a mode of speech. It is not in this vernacular sense that we propose to consider it, but in a larger and more popular signification. And thus considered, it is a subject so general and indefinite, that we cannot hope to render its discussion pointed and interesting without some limitation of the term. Shall we confine it to Turkey, or to the nations of the East who live along and beyond the Eastern Mediterranean, under the sway of the Sultan? Or shall we include those races connate with the Turk, having a Saracenic origin? Or, going farther east, entrench upon the Mongolian and Indian races, thus embracing all Asia? The subject needs restraint.

Orientalism is not merely associated with one country, race, or era. It is a complex idea, made up of history and scenery, suffused with imagination and irradiate with revelation. It is not always associated with Tartar hordes, luxurious Caliphs, tea-raising Chinese, Grand Lamas, Indian Sikhs, and three-tailed pashas. It may include these as straggling figures in the picture. But to represent it pictorially, as it first flashes upon the mind, would absorb all the colors of the chromatic scale, and break all artistic unity.

We frame to ourselves a deep azure sky, and a languid, alluring atmosphere; associate luxurious ease with the coffee rooms and flower gardens of the Seraglio at Constantinople; with the tapering minarets and gold crescents of Cairo; with the fountains within and the kiosks without Damascus — settings of silver in circlets of gold. We see grave and reverend turbans sitting cross-legged on Persian carpets in baths and harems, under palm trees or acacias, either quaffing the cool sherbet of roses, or the aromatic Mocha coffee, sipped from the fingan poised in the zarf; we picture the anxious Armenian in busy bazaars, offering the customer the amber mouthpiece of the chibouque, while he commends his attar of roses and gold-cloth; we see the smoke of the Latakia — the mild, sweet tobacco of Syria — whiffed lazily from the bubbling water pipe, while the devotee of backgammon listlessly rattles the dice; we hear the musical periods of the storyteller, relating the thousand-and-one tales to the ever-curious crowd. We perceive the spirit of silence brooding over the turbaned tombstones of the cemetery, enamored of its cypress-home and the cool shadow; Nubian slaves, with stealthy tread, following their veiled mistresses through the bazaars, or running after the haughty horsemen of the street; the caravan of camels winding its weary way over the waste, watchful against the Bedouin of the desert, and careless of the buried cities beneath. We feel the power of the Sultan and the creed of Mahomet, through Emir and Dervish sweeping over the Orient, giving at least some unity to the scene; we then bespread over all a sort of Arabian night-spell, with its deep sapphire starlight and its nightingale music from the crown of the palm tree or liquorice bush; or in dreamy repose we seem transported to some Swerga of bliss, where

‘General delights the sun Sheds on our happy being, and the stars Effuse on us benignant influences;

and we call this — Orientalism!

This is Orientalism, not as it is, but as it swims before the sensuous imagination. It is too unreal to be defined. The idea partakes of the extravagance of the Oriental mind, and would fain be invested with poetic imagery. To analyze it is to dissolve the charm. It is like the sight of Constantinople when first seen from the Bosphorus, before you round Seraglio Point into the Golden Horn, glittering in crescent, in graceful spire and swelling dome, flashing back the sun’s radiance, rising out of cypress groves, like a dream of beauty; but when you enter its streets, see its dogs, its burden bearers, its dirt, its low, mean dwellings, and look within that magic mosque and find the common cane carpet, ostrich eggs, and horsetail ornaments, and the walls bald of pictures, the dream vanishes into the glistening air!

How then shall we define this thing of dreams and dirt, despotism and dignity, called Orientalism! Is there no reality tangible to our touch? Ah! Yes; there is a serener, because a more spiritual Orientalism. It is the more substantial, because spiritual; and because spiritual, no longer local. Who has not felt, rather than pictured that tranquil Orient: its silence full of the splendors and deep with the mysteries of the Infinite? It links our thoughts to earth by its enchantment; it lifts them to heaven by its revelation. The rich stream of poetry which flows through the Bible, and penetrates our best emotions, springs from the Orient, inspired of God. Those thoughts which transcend the level of life, and raise within us aspirations

‘Wherein Eternity entwines with Time Its golden strands, and weds the soul to heaven;