Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

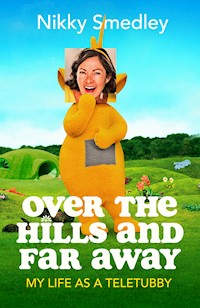

Say 'Eh-oh!' to Nikky Smedley and Laa-Laa Over the Hills and Far Away follows Nikky through the Teletubbies years, from her role as a bistro table during her audition to the show's international success and the accompanying hounding by the press. In this warm, funny, affectionate look back at life on the Teletubbies set, Nikky reveals all, including tales about dogs and asthma, raging arguments about fruit, and the games the cast and crew played to amuse themselves during long shoots in their massive costumes. Join Nikky and Laa-Laa on their extraordinary journey from the very beginning to handing the torch to another performer for the next generation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2022 bySandstone Press LtdPO Box 41Muir of OrdIV6 7YXScotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Nikky Smedley 2022

Editor: Nicola Torch

The moral right of Nikky Smedley to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Portrait of Nikky Smedley © Rebecca Knowles

TELETUBBIES and all related titles, logos and characters are trademarks of DHX Worldwide Limited dba WildBrain.

© 2022 DHX Worldwide Limited dba WildBrain. All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-914518-05-8

ISBNe: 978-1-914518-06-5

Cover design by kidethic

Ebook compilation by Iolaire, Newtonmore

Dedicated to the memory of Simon Shelton

Keepin’ it up! Keepin’ it up!

CONTENTS

Introduction

1: First, Find Your Teletubby

2: Say Eh-Oh!

3: Spirit of Yellow

4: Teletubbies Come to Play

5: The New Norma

6: And We’re On!

7: Keep Blinking and Carry On

8: Again-Again!

9: Teletubby Fever

10: The End of Days

11: Teletubbies on Tour

12: The Aftermath

13: Time For Tubby Bye-Bye

Acknowledgements

INTRODUCTION

Eh-Oh!

If you were – or had – a young child in the second half of the 1990s, you probably don’t need any help translating what that means. For those that have no idea – where have you been for the last twenty-five years? It is a phrase that springs to many people’s minds when they think of Teletubbies, and was at the heart of the initial controversy our programme stirred up when it premiered on BBC Two on March 31st 1997, before eventually becoming a well-loved feature of the cultural landscape. At its peak, Teletubbies had total global viewing figures of around three billion per annum, showing in one hundred and twenty countries and being translated into forty-five different languages, making it the second most internationally successful television programme on the planet. The only show at the time with more viewers was Baywatch, but we achieved our popularity while remaining more than modestly covered up.

Welcome to the story of how a scraggy dancer from South East London found herself part of that global television phenomenon, while at the same time remaining almost completely anonymous. This is an intimate look at the secret world behind the scenes of Teletubbyland through the eyes of Laa-Laa, the real human story from inside one of the world’s most recognisable puppets. It’s a strange claim to fame, and mine is a unique perspective on a surreal world. It’s the story of how putting on a giant furry suit can propel a person to Number One in all sorts of charts and at the same time bring them insight, courage and love.

I wouldn’t have got the job if I wasn’t a funny person, so this is quite a funny book. I was also deeply emotionally invested in the show, as were many of my colleagues, so there are touching moments too. I was part of a bizarre family working in a field in the middle of the English countryside for six years of my life, but the impact of that time stretches beyond that place and those years. Somewhere in the world, right now, a child is looking at Laa-Laa and laughing. I count myself as pretty damn lucky to be able to comfort myself with that thought.

Everything in this book happened quite a long time ago. I’ve endeavoured to recount events as accurately as possible, but inevitably it is written through the filter of my own memory and my own point of view – which is as good a truth as any, I guess. I gave a copy of the manuscript to John Simmit, who played Dipsy, to make sure it chimed with his recollection and indeed it did, both factually and emotionally. He told me he found it strange reading a collective story, but that’s the thing: although there were only ever five people who knew what it was like to be the original Teletubbies, we were such a close-knit filming unit that those six years were very much a shared experience for all involved. That sense of community shone out of the television and we formed a deep personal connection with our audience, the earliest cohorts of whom will now be all grown-up. I’m eagerly waiting to see how the world shifts when Our People come to power – remember all those predictions of doom for the children who were exposed to the perils of Teletubbies? Personally, I’m expecting the best generation yet!

Beyond the impact on the individual, what Teletubbies did more widely was open up the debate about the place of television in people’s lives, in their homes, in their worlds. It generated a conversation about how often we expose our children to screens and what we allow them to watch. This broader discussion came out of the criticism we endured. I believe the original series stands up to scrutiny as much as ever, if not more, in these strange days.

At the very core of the programme is love, and I find the warmth people across the world have in their hearts for the Teletubbies a constant source of gleeful surprise. I realise that Teletubbies is just a TV show, but it has brought a lot of joy to a lot of children – and to me. I do hope you enjoy reading this book, and that it reminds you of happy times. Most importantly, I hope it puts a smile on your face.

CHAPTER 1

First, Find Your Teletubby

Four green vinyl body bags are lying on a concrete floor, arranged in order of size. My body is second from the left and I haven’t seen it in seven years. Behind each bag is a large square wooden box, colour coded: red, yellow, green, purple. The boxes contain our heads.

I shouldn’t really be feeling as emotional as I am – I am here to do a job after all, and frankly I am a little surprised at myself. Okay girl, take a deep breath, get a grip, be a grown-up, swallow down whatever that’s all about and get on with the task in hand.

It’s the summer of 2014, almost twenty years since I first became a giant yellow puppet, and I have recently been employed as a consultant on the new, rebooted version of Teletubbies. The show is being produced by Darrall Macqueen, not Ragdoll Productions, the original creators. The rights are now owned by Canadian company DHX, who had tried to make a new version, in-house, the previous year. When they failed in their attempts, they decided it was because there was something inherently English about the show: it needed to be made in the UK. My role is to ensure authenticity, to inject some of the spirit of the original, so I was asked to come to Twickenham Studios and assist with auditions for the new cast. I’ve rarely felt as well qualified to do a job, so my usual nerves are somewhat alleviated by an unfamiliar level of confidence in my own abilities. I am also very excited. Do you ever dream of being reunited with a lost pet? That’s sort of how I feel as I stand staring at one of the vinyl bags. I want to play. I want to get into my Laa and muck about, to revisit the fun of being that character, of being all the best bits of me, of pretending the less enjoyable sides of my personality don’t exist, but also being able to get away with murder. However, there is work to be done.

The auditions are taking place in a cavernous sound stage and the head honchos will be seated behind a table at the far end of the space. This means the actors will have to walk the full length of the studio before the audition even starts. I know from experience that this walk will be beyond terrifying. Imagine you are going for a job interview, but instead of just coming into the room, you are scrutinised over a twenty-metre distance as you make your way towards those who are judging you. I’ve always hated that walk. I am so glad it’s not me making it today.

Most of the room is empty space. There is a table full of snacks with a tea urn and kettle on the right-hand side and the costumes are laid out on the floor to the left. They only arrived this morning so for the producers, the writer, the director and the other production staff, this is their first encounter with actual Teletubbies. They can’t wait to see them, and I’m on hand to demonstrate the human/Teletubby interface.

I open the yellow box. There she is! My reaction is automatic. As soon as I get my hands on the mechanisms that operate the mouth and eyes, we’re conversing. I can’t help myself – the habit of playing with my alter ego rises to the surface, switching between voices as naturally as breathing. Laa starts it, of course.

‘Where the bloody hell have you been?’

‘Sorry, I—’

‘Sorry? Sorry is not good enough. I’ve been in that sodding box for years. You didn’t write, you never called, you missed our anniversaries . . .’ I could go on, lost in my own little puppeteer’s psychosis, but we must curtail the catch-up. It’s time to stop larking about, be professional and bring Laa-Laa to life for everyone else in the room.

My body knows exactly where to go to get myself into the suit: how high I need to lift my legs, the angle of entry, where to hold onto the harness to bring it up around my waist, the exact dip of my shoulders needed to hitch the upper section into position. My physical memory is absolutely in charge. The wiggle I do to settle everything in place is probably the exact same wiggle I did for six years and more. The texture of the fur feels like home, the slight rub of the padding behind the knees a familiar discomfort, as is the weight – initially quite bearable but becoming heavier by the second. Then I lift the puppet head by its ears and when my arms are fully extended upwards, I duck my neck, dip my head under the cowl and slip into the skullcap, taking the mechanisms in my hands. Left for eyes, right for mouth. I am back: ‘Eh-Oh! Is-y Laa-Laa!’

Physically uncomfortable though it is, being back inside Laa gives me a deep-seated sense of security. This is something I know so completely I don’t even have to think about it. I engage in a brief display of classic Teletubby puppeteering. The years apart melt away and I automatically know how to manipulate the controls to make the crowd warm to the character. Through the tiny gap of the mouth, I see the faces of my audience change. I watch the tilt of their heads as they lift their gaze to address the eyes of Laa-Laa, already captivated by the power of the puppet, allowing themselves to forget the human inside. I know the expression on their faces so well. No matter how much they tell themselves they are looking with professional eyes, I know they will be sucked into my reality. After only a few minutes – I don’t want to get too sweaty – I lift the head off again, smiling at Laa’s face the way you would at a sidekick, a mischievous accomplice or your best mate at school who always backs you up and joins your crazy schemes. I know what she has allowed me to get away with in the past and it makes me chuckle that we are still a formidable team. I turn back into my human self – puny in comparison to the size and dimensions of Laa-Laa – and leave the new bosses to study the workings of the puppet. My puppet.

It is decided that we will work with all the actors who are auditioning through the morning to see their set pieces, read some scripts, and try a little improvisation. Then we’ll have a cull and those that remain can try on the costumes in the afternoon. Two candidates who make it through are Rebecca Hyland and Nick Kellington. I’ve worked with them before, helping them train for their roles as Upsy Daisy and Iggle Piggle in In The Night Garden, and now they are hoping to play Laa-Laa and Dipsy respectively. I’m glad to see them both. I couldn’t think of better performers to take on the mantle of the characters John Simmit and I had created. They were well versed in the tone of Ragdoll’s creations, familiar with the physical demands of this type of work and had proved themselves up to the job. Hard-working, good-natured, strong, funny and playful – what more could we want in a Teletubby?

In addition, I genuinely liked them. I liked the idea of Rebecca as Laa-Laa and I was very happy with this choice of who was going to ‘be me’. Except that ‘being me’ wasn’t really the job in hand as Rebecca would have to find her own Laa. Darrall Macqueen were very keen to stay faithful to the original Ragdoll version, but they also wanted to make their own mark on the show. The same would be true of the performers. A straight imitation of what had gone before was not what was required. It would be boring for them and a waste of their own individual skill and style.

The way I remember it, there was no question about which four of the performers that came to us that day were the right choice. The selection process could have developed into a long-winded nightmare, but there they were – immediately obvious. I don’t even think there was much discussion around the decision, and certainly no argument. Rachelle Beinart had exactly the right mixture of feisty and vulnerable for Po, with a list of relevant credits as long as your arm, and it was a miracle that Tinky Winky’s innocent eccentricity was personified so naturally by Jeremiah Krage. The four of them together looked like a pretty good line-up to me and I was excited to see how they would come across once inside the suits. The same designer who created our original costumes had been brought on board to make a whole new set of Teletubbies for the rebooted programme. It was going to take her some time to get them made, so the cast would be using our suits in the meantime – properly laundered, one would hope!

After lunch, Rebecca is primed to try out the yellow puppet, and the wardrobe department are on hand to learn, from me, the mechanics of the transformation. I help Rebecca into the body, then sit her down and feed the mechanisms for the head down the sleeves into her hands. Then I lower the puppet head onto her human one and fasten the back of the bodysuit. It’s strange to be on the other end of the procedure and although I am trying to be as clear as possible in my demonstration, part of my brain is also browsing through a gallery of my past dressers and running through a montage of shared intimacies and in-jokes. When Rebecca is fully enclosed in my Laa-Laa, I stand back to look at her. This has never happened before. I’ve never seen someone else in my Teletubby. On set, we had put a director or two into a suit so that they could experience a little of the effort needed to obey their orders, but we’d always used Dipsy. I knew that members of the wardrobe department had also worn my suit in the course of their labours, but I’d never seen it. I used to joke, Judge Dredd style: ‘I am the Laa!’ The one, the only.

When people found out what I did for a living, they’d quite often ask, ‘Were you just the body?’

‘No,’ I’d reply, ‘I was everything: body, voice, soul.’

‘Was it always you or were there other actors doing it too?’

‘Just me. Only me. I am the Laa!’ The one, the only.

And now I am not.

I wasn’t prepared for the emotional impact of that. There was someone else in my Laa and this was how it was going to be from now on. It wasn’t my job any more and she wasn’t my Laa any more – it was time to let go. I was now an ex-Teletubby. I wasn’t going to be the one making the crew laugh, joking around with my dresser, enjoying appearances on other TV shows, sharing the most surreal of experiences and calling it work, being paid to be funny and loving, being loved. I could no longer take it for granted that whenever I saw the image of Laa-Laa, it was me.

All sorts of things were wrapped up in this wave of emotion: getting older, not being able to deal with the physical stresses like I had eighteen years previously, not working in the television industry any more. Not being special. Not being the Talent. The sense of self-worth that the job had given me should have been immutable. It shouldn’t have mattered that someone else was now doing my job – that’s what happens in the grown-up world. But somehow it did matter. I felt less. I felt loss.

******

ARTISTES WITH STAMINA REQUIRED

for new children’s television programme.

Unusual personalities and backgrounds especially welcome.

Ragdoll Productions

This was the advertisement in the Stage that caught my eye in September 1995. I had spent the previous fifteen years working as a performer, mostly dancing, mostly with my own dance company, mostly poor. Now I was about to turn thirty-three and it was time for a new chapter.

Age was catching up with me and with my dodgy knees in particular. All dancers at some point have to face up to the fact that their bodies are no longer capable of doing what they did when they were younger. The slope is now downwards. You can no longer improve. You will never become better at your job. You must come to terms with the truth that your glory days as a dancer are over. At this point, a part of you dies. The majority of you, however, is still alive and has a couple of alternatives. You can adjust how you dance, where you dance, when you dance, and carry on with a career that is adapted to the physical shifts you are experiencing, or you can quit. I chose the latter for reasons financial. Being brutally honest with myself, I didn’t think I was worth paying money to watch any more. I’d never been particularly confident in my abilities as a dancer. I knew I relied heavily on performance skills, on musicality, on acting ability and on a certain emotional quality that managed to mask my less than perfect technique. Now what technique I had was becoming more difficult to maintain and I didn’t think I’d be able to get away with this trick any more.

Also, I was fed up with being dirt poor.

I’d enjoyed a feast or famine existence – mostly famine – surviving courtesy of the Department of Health and Social Security for fifteen years. It’s not that I was idle, far from it. I’d been creating dance theatre since I left college, running my own company, staging my own spectacles, touring and working with other choreographers. I was successful in every way except financially. If I was cast in a music video, landed a modelling job or nailed a short commercial contract, I could be pulling in a couple of hundred quid a day but because of the vast swathes of time when I had no paid work whatsoever, these funds fell into the bottomless pit of debt, making no impact on my day-to-day life. No, what my day-to-day life looked like was seven piles of three pound coins, lined up on my desk and representing one week’s disposable income. Each morning I’d sit and toy with that day’s allotment, the coins falling between my thumb and middle finger – thump, ding, ding, thump, ding, ding – as I pondered whether to eat or dance. A dancer should do class every day to maintain tiptop condition and at the time a professional dance class cost three pounds, leaving precisely nothing to spend on food. Sometimes friends were kind and fed me, sometimes I could snaffle the dregs at the end of the day from Lewisham’s market stalls, sometimes I could eke out meagre supplies to last a couple of days. Mostly it was a compromise between my stomach and the rest of my body.

The level of poverty I was living in hadn’t even registered when I was younger. Life threw miracles my way – I was doing what I loved with people I loved and I was grateful for that. Right up to the hilt, all the way home, with knobs on. But now I was in my thirties, my discontent persisted like a mewling kitten round my ankles.

Then one day, I made a decision. My sister laughed at me when I told her.

‘I’ve decided I’m not going to be poor any more.’

‘What are you going to do?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Well, what kind of a decision is that?’

‘I don’t know how; I’ve just decided I’m not going to be poor any more.’

‘You can’t just decide that. You have to do something.’

‘Well, I will. I’m not going to just sit on my arse. I realise I have to give the universe the opportunity to help me.’

‘To help you not be poor any more?’

‘Yes. It will happen. I just don’t know how.’

‘Prrrfff!’

‘The money will come.’

I said it to myself. All the time. Every day. It became my mantra. As I got on with my daily life I said silently to myself, over and over again, ‘The money is coming. The money is coming’, seeing in my mind’s eye an endless stream of notes flying towards me as if magnetised.

I threw my heart and soul into my new decision. I went to the library every day to check employment opportunities in the papers and trade magazines. I trawled the notice boards of dance studios and art centres. I auditioned for roles big and small. I quaked with nerves through formal interviews. I applied to be a Christmas Elf at Harrods and Selfridges. I wrote glowing references for myself from the Tooth Fairy and the Easter Bunny, along with a damning one from the Bogeyman. I thought this was a touch of genius and showed my commitment to the role. The department stores thought I was insane.

Then one Thursday, from the back pages of the Stage, a new chapter beckoned. It was the line, ‘Unusual personalities and backgrounds especially welcome’ that caught my eye – what kind of an employer would put those words in their advertisement? The kind that might employ me, that’s who!

I have no memory of what I sent them in response, but a couple of weeks later I came home to find an envelope from Ragdoll Productions waiting patiently on the mat. Good quality stationery as I recall. The letter told me I had been selected to audition and I was to be at The London Welsh Centre in Camden at 9.00am the following morning. The next morning! It was already 6.00pm. I’d spent all day at a hair studio being coiffured in preparation for a modelling job the following week. The vibe was 1960s pop-art and Bridget Riley monochrome. I was to wear black and white PVC boots with a matching belted mini dress that squeaked when I danced. My hair was cut in two layers, a short asymmetric bob dyed platinum blonde beneath a contrasting geometric shape dyed black on top. The style hadn’t really worked. I looked less ready for swinging London and more ready to have them swinging from the gallows. You know the judge in a period courtroom drama who has to put a square of black cloth on top of his white wig before he passes the death sentence? That was me... ‘And may God have mercy on your soul.’

I couldn’t do anything about that – I had to figure out what I was going to do at tomorrow’s audition. They wanted me to perform something suitable for three-year-old children, and a humorous piece for adults. Both were to be three minutes in length. I panicked and flapped and then did what any sensible person in my position would do – I went to my local pub and drank two glasses of wine (while fending off wisecracks about my ridiculous hair). The wine calmed my brain, and my brain gave me an idea. In a previous life, with my dance company Geographical Duvet, I had made a show about love named What is This Thing Called? which had followed the story of a couple through meeting, dating, wedding, birthing and falling apart. Company member Rachel and I had played the part of the couple’s special bistro – yes, funny – and I had worn a large plywood disc around my waist covered in a red and white gingham cloth with a matching parasol on my head, as the bistro table. The cloth had perished long ago, but I had the plywood disc in my shed and with some refurbishment I could make it work as a table again. I could write a little song about being in love with a chair, a short tale of unrequited love.

I am a table.

I am in love with a chair.

But the chair.

Doesn’t care.

For me.

Yes, it was coming together. I could address the children – the imaginary three-year-old audience – directly. ‘Poor me, what shall I do?’ That type of thing. Yes, I could make that work. Sad clown in table form. No-one else was going to do that. Stand out – that’s what they say isn’t it?

Twenty-five years on from its one and only performance, I can still remember the tune.

As soon as I got home, I searched the shed for my current plywood disc/future table, unprepared for the number of spiders and their webs. Ick. I was successful in my search. Indoors, I found a spider-free length of shiny orange cloth I’d previously worn as a sari and stapled it onto the wood to act as a tablecloth. I rehearsed the song and the scene in my kitchen until it was precisely three minutes in length – I take direction well – and committed it to memory. Done. 9.00pm. Then I turned my attention to the other task.

I rang my friend Robin – who knew all my best stories – and explained the situation to him. He replied confidently with: ‘Why don’t you tell them the one about the time your dad burned your arse on the carpet?’

‘Do you think it’s funny enough?’

‘The way you tell it – yes.’

Great, I didn’t even need to rehearse that one, I knew it so well. I ran through it a couple of times anyway for good measure, practised the table scene again, packed everything up and was soon ready to get an early night. I wanted as many hours as possible to toss and turn and fret and worry about the fact that I was tossing and turning and fretting and worrying instead of sleeping. Then the alarm went off.

I’m not sure if I mentioned that the plywood disc was as wide as I was tall and now had cloth stapled to it and ropes wrapped around it. What made it worse was the two trains and tube I had to catch to get across London – and at rush hour. It was a hoot! I’ve always found people are much more helpful than expected when they see someone carrying a cumbersome item. Maybe it’s the surprise entertainment value that predisposes them to lend a hand? At any rate, relying on the kindness of strangers, I managed to reach King’s Cross tube station and wend my way down Gray’s Inn Road, wavering from side to side as the plywood on my shoulder acted like a sail in the breeze.

What with wielding the disc and sharing a giggle with fellow Londoners, I had forgotten to be nervous until I was outside the door of The London Welsh Centre. I was early, but I wasn’t going to loiter in the street with this thing. I entered shaking and sweating, but hoping there’d be some sort of foyer where I could wait. And a loo where I could wee.

I walked into a flurry of producers, all running around preparing the space, making coffee and handing each other lists. They had set up a horseshoe of around thirty chairs for the auditionees, facing a row of tables for the auditioners. This format was more akin to a drama workshop than an audition, but I rather liked that we were all in it together. I drifted about uncertainly near the doorway, with my giant plywood disc on my shoulder and my crazily contrasting hair. They definitely didn’t need to ask if I was there for the audition.

I parked my table-top, took the penultimate chair on the right arm of the horseshoe and waited for the others to fill up. Then I watched the other chairs empty one by one as each of the hopefuls performed for the judges – mostly for longer than six minutes. Tch! Considering I was only sitting and watching, I expended an awful lot of energy. When somebody was really good, I momentarily forgot the context, sat back and enjoyed the show. Then when I snapped back into the room, it was with a suddenly accelerated heartbeat that took my breath away, quivered my body and flushed perspiration onto my brow and in various crevices. I’m never going to get this job, that person is much funnier than me, I thought. When somebody was really bad, I started to doubt whether I wanted this job anyway, then I’d have to admonish myself for being cocky, remember the good people, and the shaking and sweating would start again. A few hopefuls had interpreted, ‘Unusual personalities and backgrounds’ to mean ‘downright strange’. They waggled badly made sock puppets and got confused about whether it was the puppet or themselves telling the story of the tramp in the frozen food section of Safeway, at some volume, in a bikini. Not really, I made up that last bit.

Hours later, it was my turn. Crazy Hair Girl. I got into my table and apologised for my hair. I felt like the strangest hopeful yet. I did my thing exactly how I’d planned, for good or bad and for precisely three minutes. Then I removed the table and said, ‘I wasn’t sure what to do for this “humorous piece for adults” bit, so I rang my friend Robin who said I should tell you about the time my dad burned my arse on the carpet.’ An intake of breath and a glimmer of horror from my audience ensued – exactly as hoped for – and I began the story:

An archetypal domestic scene: the lounge in the house I grew up in. I’m around nine years old. It’s evening and I’m waiting up to see my dad before I go to bed. I’ve had a bath and I’m in my nightie, sitting on the floor leaning against an armchair watching telly. Mum is on the sofa, managing to watch and knit at the same time. I find the clicking of her needles comforting. Dad hates it. He’s late. Mum sighs periodically. Her sighs say, ‘He’s in the bloody pub, isn’t he? It’s gone eight o’clock. Typical.’ His car pulls up outside. Another sigh. The clicking continues as I listen to Dad come in, dump his bags, take off his coat and shoes, put on his slippers – not too drunkenly by the sound of things – and finally open the door to the lounge. His attention is instantly on me, ‘There she is! There’s my girl!’ Yeah . . . he is a bit pissed.

He squats a little on his haunches, bending forward and reaching his arms out towards me, holding my gaze with his daft grin. He grabs my ankles and starts to run backwards and sideways, pulling me around the room. It could have been quite fun, but it wasn’t because of the bare bum/cheap carpet interface. I am screaming my head off as the dragging and concurrent carpet burning persists. Mum doesn’t look up from her knitting, ‘Stop it Cyril, you’re hurting her.’

Dad disagrees, ‘No I’m not, she’s enjoying it. Look.’ He drags me with fresh vigour. He’s having a great time. I try and persuade him that Mum is right, by clearly stating my case, ‘Aaaaaaaaaaaaah!!!’

When my screaming turns to actual crying, he stops. He is more disappointed in me than apologetic – I am no fun – and he’s insistent that the whole episode has been a jolly lark.

Oh! The sting of the TCP after the event, equally as eye-watering as the creation of the carpet burns. The compensation was being able to scratch and pick at the scabs on my bum cheeks without anyone telling me off for it, because I was the victim. Nuh Nuhnuh Nuh Nuh!

They laughed in all the right places, but these were professionals – just because they made laughing noises, it didn’t necessarily mean they thought it was funny. Still, better than blank, silent stares.

One more person gave of themselves, but I was gazing into space hearing only the pounding of my blood and the ringing in my ears until the adrenaline eased off and it was time to drag my plywood disc and my spent self back to South East London.

This was the beginning of a long-drawn-out process. It was torturous, waiting for the expected letter of rejection after every follow-up audition. Those of us still in the running were asked back to improvise around various themes, to try out potential scenarios, to learn a little more about the mysterious Teleteddies, as the show was originally called. Then the big boss lady, the head honcho, Anne Wood, came in to explain to a group of around twenty of us what exactly it was she wanted to achieve with her new creative baby. And I fell in love.

Up until this point, I’d been treating the whole thing as I would any audition process: I might get the job, I might not get the job, just do my best, lap of the Gods. But everything changed when I listened to Anne explain the show. She talked about making an anti-Power Rangers for very small children, about creating something that made the viewing child feel the love, about how there was nothing on television specifically made for very young children, how she wanted to make that something, and make it with high production values. The more she talked, the more it became apparent that she had identified one hell of a niche. She continued with articulate passion, explaining the philosophy behind the show. She wanted it to speak to children directly rather than through an adult, to give them faith in their own ability to learn, to connect with the imaginative life of the child, to be innocent fun, full of love, and jam-packed to the brim with top quality integrity.

I was spellbound. I was hooked. I could see the future.

‘Oh my God! This is going to be HUGE!’ I really did think that.

Now I definitely wanted the job; now it meant something.

More auditions whittled the field down to a handful of hopefuls as Christmas loomed on the horizon like a matinée idol on a camel. During this agonising time, I described what little I knew about the show to a friend who said, ‘It’s like they made a job that had your outline and all you had to do was show up and fill it.’ I didn’t share her certainty. But suddenly there were only three of us in a rehearsal studio with Anne and Andy Davenport, the co-creator and writer. John Simmit was a Jamaican comedian from Birmingham whom Anne had had lined up for some months. John was solid. He cut quite an intimidating figure, if you didn’t know he was a complete sweetie. This was something he enjoyed – played up even. But when he talked to his daughter on the phone, his whole demeanour changed, not just his voice, and he betrayed the kind-hearted, caring man he truly was – and still is. I believe this softer side was what drew Anne to him.

Then from the London auditions were me and Dave Thompson, another comedian, based in Lambeth. As flighty as John was rooted, Dave was an oddball and I liked him right off. His main claim to fame up to that point was being part of a cabaret act known for dancing naked, but for a couple of strategically placed balloons. This might not make him seem a good fit for children’s television, but there was something quirky and unorthodox about Dave that reminded you of a certain kind of child.

At this point, there was no-one to play the smallest character. A couple had been tried but rejected, and the role was yet to be filled. Anne told us she was struggling to find someone with the right personality, someone who was devoid of pathos. I didn’t know if she was trying other combinations of performers before choosing the final four, but there didn’t seem to be anyone else around. It was starting to look like I was in with a chance. Dare I believe? Maybe not yet.

Anne was admirable. My hero. She was not a woman of great physical stature, but she had an undeniable presence. She’d worked in television for decades, having given us Roland Rat, Pob’s Programme and Tots TV to name but a few, before punting everything she’d earned in the last fifteen years on this new show. That took some balls. Teletubbies was now the name of the show, as there was some sort of copyright issue with the original title, Teleteddies. It was a commission from the BBC, but Anne had also invested all she owned. I was small fry compared to her, but I recognised the same fervour, the same complete commitment and drive and the same dedication to the task at hand that I have experienced whenever I’ve been in the throes of a new creative project. Despite her air of authority, she had a tremendous sense of fun and play – and she was really good company.

Anne started her working life in teaching and that background goes some way to explaining her preternatural understanding of small children, but it doesn’t explain it totally. Some people just have it. Maybe it’s because they remember their own childhood more vividly. They seem to have a connection, as if an umbilical cord of awareness runs through the years enabling them to get right back in touch with the child’s mind. Andy has it too, but in a less visceral way. His understanding came through a more obviously artistic filter as well as from the intellectual grounding from his studies of children’s speech and communication. Lithe and handsome in an understated way, his gentle energy was a perfect foil to Anne’s passionate bluster. I was fascinated by them both. More than anything I wanted to spend the next chapter of my life working for them and learning from their expertise.

During the years when I ran my own company, I had always strived to make dance accessible. It seemed to me paradoxical that though so many people loved to dance themselves as an informal recreational activity, performed dance wasn’t that popular as a spectacle. Although, if you looked around at the theatrical dance available when I started out in the early eighties, it was pretty po-faced – no pun intended. When some long-suffering boyfriend or parent would come up to me after a show and say, ‘I didn’t think I liked dance, but I liked that’ I would feel that my work was done. Although driven by the desire to make dance more accessible, I never specifically set out to reach children. Nevertheless, they enjoyed our shows and we’d even played some children’s festivals. I realised that by working with Anne and Andy I could learn untold secrets about the workings of the child mind, and by gaining a better understanding of how to make meaning for children, maybe I would also learn more about humans in general.

On that final audition day, with just the three of us, we were shown sketchy pencil drawings of chubby little characters with televisions in their tummies and aerials on their heads, running over hillocks under the gaze of a magical windmill. After being sworn to secrecy we were sent away to count our chickens and though years in show business had taught me not to, I allowed myself to hope that this time I would get the lucky break, that the magical light would shine on me and the new chapter I was so desperate for would begin and free me from poverty and pain.

The romance in my memory tells me it was Christmas Eve when I got the phone call. Having waited for days, my hope had faded and I’d resolved to enjoy the seasonal festivities and then start 1996 with a fresh new outlook. I do remember that I was in bed, though awake – probably to keep warm – and it was Sue James, the series producer, who called to tell me that the job was mine. I was to be a Teletubby: I was to be Laa-Laa. I was to be employed – and yellow.

Best. Christmas present. Ever.

I later learned that Anne hadn’t been sure about me at all. It was Andy who was my champion, absolutely sure. He told her, ‘Oh yes! Crazy Hair Girl? We’ve got to have her!’ Thanks Andy.

CHAPTER 2

Say Eh-Oh!

1996. A new year and a new experience. I had been offered a contract for three years’ work. Who knew such a thing existed? Being a fully paid-up member of the actors’ union Equity, I rang them for some advice. They told me that as it wasn’t an Equity contract – it had been drawn up independently by Ragdoll Productions – it was outside their jurisdiction and they could offer me no help. Zero. Zilch. Nada. Could they maybe give me an opinion? Some pointers? No, they could not. How disappointing. I didn’t have an agent so it looked like I was on my own.

The contract included a ‘Worldwide Buyout’ clause, meaning if the programme was sold abroad and broadcast, anywhere other than the UK, we would be entitled to precisely zero repeat fees. This wasn’t an unusual clause at the time, though in the good old days royalties would have been paid as a matter of course. American friends were amazed: ‘That would never happen in the States, the Screen Actors Guild is way too powerful. No company could ever get away with not paying repeat fees in the US. If the show was being made here, you’d be making a fortune.’ That may have been true, but if the show was being made in America, I wouldn’t have got the job, so I didn’t think I was in a position to complain.

It’s surprising how often strangers ask me about my royalty situation. I know! Some people have no shame. Mostly, they assume I receive money every time the programme is broadcast. They seem to think I sleep on a mattress of money.

‘Must be nice getting that royalty cheque every month?’

‘Honestly, do you think I’d be here if that were the case? If I got paid every time a Teletubbies episode was shown, I’d be on my tropical island right now thank you very much!’

I was in the middle of a pub pool tournament when this line of probing came up and I fronted it out – I was in a competitive frame of mind, obviously – asking the bloke outright, ‘How much do you think I earn?’

‘I don’t know – £250,000?’

I laughed in his face.

Regardless of the royalty situation, the weekly wage for filming Teletubbies