Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Cheapest Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Pellucidar is a fictional Hollow Earth milieu invented by Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs for a series of action adventure stories. In a notable crossover event between Burroughs' series, there is a Tarzan story in which the Ape Man travels into Pellucidar. The stories initially involve the adventures of mining heir David Innes and his inventor friend Abner Perry after they use an "iron mole" to burrow 500 miles into the Earth's crust. Later protagonists include indigenous cave man Tanar and additional visitors from the surface world, notably Tarzan, Jason Gridley, and Frederich Wilhelm Eric von Mendeldorf und von Horst. Geography: In Burroughs' concept, the Earth is a hollow shell with Pellucidar as the internal surface of that shell. Pellucidar is accessible to the surface world via a polar opening allowing passage between the inner and outer worlds through which a rigid airship visits in the fourth book of the series. Although the inner surface of the Earth has an absolute smaller area than the outer, Pellucidar actually has a greater land area, as its continents mirror the surface world's oceans and its oceans mirror the surface continents. A peculiarity of Pellucidar's geography is that due to the concave curvature of its surface there is no horizon; the further distant something is, the higher it appears to be, until it is finally lost in the atmospheric haze. Pellucidar is lit by a miniature sun suspended at the center of the hollow sphere, so it is perpetually overhead wherever one is in Pellucidar. The sole exception is the region directly under a tiny geostationary moon of the internal sun; that region as a result is under a perpetual eclipse and is known as the Land of Awful Shadow. This moon has its own plant life and (presumably) animal life, and hence either has its own atmosphere or shares that of Pellucidar. The miniature sun never changes in brightness, and never sets; so with no night or seasonal progression, the natives have little concept of time. The events of the series suggest that time is elastic, passing at different rates in different areas of Pellucidar and varying even in single locales.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 295

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Pellucidar

By

Edgar Rice Burroughs

ILLUSTRATED &

PUBLISHED BY

E-KİTAP PROJESİ & CHEAPEST BOOKS

www.cheapestboooks.com

www.facebook.com/EKitapProjesi

Copyright, 2014 by e-Kitap Projesi

Istanbul

ISBN: 978-615-5564-413

* * * * *

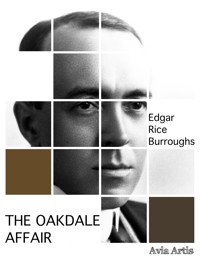

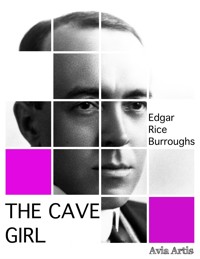

About Author

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American writer, best known for his creations of the jungle hero Tarzan and the heroic Mars adventurer John Carter, although he produced works in many genres.

Early life:

Burroughs was born on September 1, 1875, in Chicago, Illinois (he later lived for many years in the suburb of Oak Park), the fourth son of businessman and Civil War veteran Major George Tyler Burroughs (1833–1913) and his wife Mary Evaline (Zieger) Burroughs (1840–1920). His middle name is from his paternal grandmother, Mary Rice Burroughs (1802-ca. 1870).

Burroughs was educated at a number of local schools, and during the Chicago influenza epidemic in 1891, he spent a half year at his brother's ranch on the Raft River in Idaho. He then attended the Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, and then the Michigan Military Academy. Graduating in 1895, and failing the entrance exam for the United States Military Academy (West Point), he ended up as an enlisted soldier with the 7th U.S. Cavalry in Fort Grant, Arizona Territory. After being diagnosed with a heart problem and thus ineligible to serve, he was discharged in 1897.

Bookplate of Edgar Rice Burroughs showing Tarzan holding the planet Mars, surrounded by other characters from Burroughs's stories and symbols relating to his personal interests and career

Some seemingly unrelated short jobs followed. Some drifting and ranch work followed in Idaho. Then, Burroughs found work at his father's firm in 1899. He married childhood sweetheart Emma Hulbert in January 1900. In 1904 he left his job and found less regular work; some in Idaho, later in Chicago.

By 1911, after seven years of low wages, he was working as a pencil sharpener wholesaler and began to write fiction. By this time, Burroughs and Emma had two children, Joan (1908–1972), who would later marry Tarzan film actor James Pierce, and Hulbert (1909–1991). During this period, he had copious spare time and he began reading many pulp fiction magazines. In 1929 he recalled thinking that

... If people were paid for writing rot such as I read in some of those magazines, that I could write stories just as rotten. As a matter of fact, although I had never written a story, I knew absolutely that I could write stories just as entertaining and probably a whole lot more so than any I chanced to read in those magazines.

Career:

Aiming his work at the pulps, Burroughs had his first story, Under the Moons of Mars, serialized by Frank Munsey in the February to July 1912 issues of The All-Story —under the name "Norman Bean" as a precaution to protect his reputation. (Under the Moons of Mars inaugurated the Barsoom series. It was first published as a book by A. C. McClurg of Chicago in 1917, entitled A Princess of Mars, after three Barsoom sequels had appeared as serials, and McClurg had published the first four serial Tarzan novels as books.)

Burroughs soon took up writing full-time and by the time the run of Under the Moons of Mars had finished he had completed two novels, including Tarzan of the Apes, which was published from October 1912 and went on to become one of his most successful series. In 1913, Burroughs and Emma had their third and last child, John Coleman Burroughs (1913–1979).

Burroughs also wrote popular science fiction and fantasy stories involving Earthly adventurers transported to various planets (notably Barsoom, Burroughs's fictional name for Mars, and Amtor, his fictional name for Venus), lost islands, and into the interior of the hollow earth in his Pellucidar stories, as well as westerns and historical romances. Along with All-Story, many of his stories were published in The Argosy magazine.

Tarzan was a cultural sensation when introduced. Burroughs was determined to capitalize on Tarzan's popularity in every way possible. He planned to exploit Tarzan through several different media including a syndicated Tarzan comic strip, movies and merchandise. Experts in the field advised against this course of action, stating that the different media would just end up competing against each other. Burroughs went ahead, however, and proved the experts wrong — the public wanted Tarzan in whatever fashion he was offered. Tarzan remains one of the most successful fictional characters to this day and is a cultural icon.

* * * * *

Preface (About the Book)

Dust-jacket illustration from first edition of Pellucidar

Pellucidar is a fictional Hollow Earth milieu invented by Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs for a series of action adventure stories. In a notable crossover event between Burroughs' series, there is a Tarzan story in which the Ape Man travels into Pellucidar.

The stories initially involve the adventures of mining heir David Innes and his inventor friend Abner Perry after they use an "iron mole" to burrow 500 miles into the Earth's crust. Later protagonists include indigenous cave man Tanar and additional visitors from the surface world, notably Tarzan, Jason Gridley, and Frederich Wilhelm Eric von Mendeldorf und von Horst.

Geography:

In Burroughs' concept, the Earth is a hollow shell with Pellucidar as the internal surface of that shell. Pellucidar is accessible to the surface world via a polar opening allowing passage between the inner and outer worlds through which a rigid airship visits in the fourth book of the series. Although the inner surface of the Earth has an absolute smaller area than the outer, Pellucidar actually has a greater land area, as its continents mirror the surface world's oceans and its oceans mirror the surface continents.

A peculiarity of Pellucidar's geography is that due to the concave curvature of its surface there is no horizon; the further distant something is, the higher it appears to be, until it is finally lost in the atmospheric haze.

Pellucidar is lit by a miniature sun suspended at the center of the hollow sphere, so it is perpetually overhead wherever one is in Pellucidar. The sole exception is the region directly under a tiny geostationary moon of the internal sun; that region as a result is under a perpetual eclipse and is known as the Land of Awful Shadow. This moon has its own plant life and (presumably) animal life, and hence either has its own atmosphere or shares that of Pellucidar. The miniature sun never changes in brightness, and never sets; so with no night or seasonal progression, the natives have little concept of time. The events of the series suggest that time is elastic, passing at different rates in different areas of Pellucidar and varying even in single locales.

Culture:

Pellucidar is populated by primitive people and prehistoric creatures, notably dinosaurs. The region in which Innes and Perry initially find themselves is ruled by the cities of the Mahars, intelligent flying reptiles resembling Rhamphorhynchus with dangerous psychic powers, who keep the local tribelets of Stone Age human beings in subjugation. Innes and Perry eventually unite the tribes to overthrow the Mahars' domain and establish a human "Empire of Pellucidar" in its place.

While the Mahars are the dominant species in the Pellucidar novels, they seem confined to their handful of cities. Before their overthrow they use the Sagoths (a race of gorilla-men who speak the same language as Tarzan's apes) to enforce their rule over the human tribes within the area which they rule. Though Burrough's novels suggest that the Mahar realm is limited to one relatively small area of the inner world, John Eric Holmes' authorized sequel Mahars of Pellucidar indicates there are other areas of Mahar domination.

Within and outside the Mahars' domain are scattered independent human cultures, most of them at the stone age level of development. Technically more advanced exceptions include the Korsars (corsairs), a maritime raiding society descended from surface-world pirates, and the Xexots, an indigenous Bronze Age civilization. All or most of the human inhabitants of Pellucidar share a common world-wide language.

Races:

Pellucidar also harbors enclaves of various nonhuman or semi-human races. There are:

· The Ape Men - A race of ape-like black creatures with prehensile tail and are arboreal.

· The Azarians - A race of primitive man-eating giants.

· The Brute-Men - The Brute-Men are peaceful gorilla-like farmers. They are sometimes called "Gorilla-Sheep" for the sheep-like appearance of their faces.

· The Coripies - A subterranean race, also known as the Buried People, the Coripies are a race of short eyeless carrion-eaters.

· The Ganaks - A race of horned bison men.

· The Gorbuses - A subterranean race of cannibalistic albinos who are apparently resurrected surface-world murderers.

· The Horibs - A race of ferocious dinosaur-riding reptile men.

· The Mahars - The master race of Pellucidar who resemble Rhamphorhynchus.

· The Sabertooth Men - A race of ape-like black creatures with prehensile tails. They are cannibals with dagger-like tusks.

· The Sagoths - The gorilla-like servants of the Mahars.

Table of Contents

Pellucidar {Illustrated}

About Author

Preface (About the Book)

Chapter I: Lost On Pellucidar

Chapter II: Travelling With Terror

Chapter III: Shooting the Chutes—And After

Chapter IV: Friendship And Treachery

Chapter V: Surprises

Chapter VI: A Pendent World

Chapter VII: From Plight To Plight

Chapter VIII: Captive

Chapter IX: Hooja's Cutthroats Appear

Chapter X: The Raid On the Cave-Prison

Chapter XI: Escape

Chapter XII: Kidnaped!

Chapter XIII: Racing For Life

Chapter XIV: Gore And Dreams

Chapter XV: Conquest And Peace

PELLUCIDAR

by

Edgar Rice Burroughs

{Illustrated}

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

Murat Ukray {e-Kitap Projesi}

Original map of Pellucidar, from the first edition of Pellucidar (1915)

FOREWORD

To the Reader of this Work:

PROLOGUE

Several years had elapsed since I had found the opportunity to do any big-game hunting; for at last I had my plans almost perfected for a return to my old stamping-grounds in northern Africa, where in other days I had had excellent sport in pursuit of the king of beasts.

The date of my departure had been set; I was to leave in two weeks. No schoolboy counting the lagging hours that must pass before the beginning of "long vacation" released him to the delirious joys of the summer camp could have been filled with greater impatience or keener anticipation.

And then came a letter that started me for Africa twelve days ahead of my schedule.

Often am I in receipt of letters from strangers who have found something in a story of mine to commend or to condemn. My interest in this department of my correspondence is ever fresh. I opened this particular letter with all the zest of pleasurable anticipation with which I had opened so many others. The post-mark (Algiers) had aroused my interest and curiosity, especially at this time, since it was Algiers that was presently to witness the termination of my coming sea voyage in search of sport and adventure.

Before the reading of that letter was completed lions and lion-hunting had fled my thoughts, and I was in a state of excitement bordering upon frenzy.

It—well, read it yourself, and see if you, too, do not find food for frantic conjecture, for tantalizing doubts, and for a great hope.

Here it is:

DEAR SIR: I think that I have run across one of the most remarkable coincidences in modern literature. But let me start at the beginning:

I am, by profession, a wanderer upon the face of the earth. I have no trade—nor any other occupation.

My father bequeathed me a competency; some remoter ancestors lust to roam. I have combined the two and invested them carefully and without extravagance.

I became interested in your story, At the Earth's Core, not so much because of the probability of the tale as of a great and abiding wonder that people should be paid real money for writing such impossible trash. You will pardon my candor, but it is necessary that you understand my mental attitude toward this particular story—that you may credit that which follows.

Shortly thereafter I started for the Sahara in search of a rather rare species of antelope that is to be found only occasionally within a limited area at a certain season of the year. My chase led me far from the haunts of man.

It was a fruitless search, however, in so far as antelope is concerned; but one night as I lay courting sleep at the edge of a little cluster of date-palms that surround an ancient well in the midst of the arid, shifting sands, I suddenly became conscious of a strange sound coming apparently from the earth beneath my head.

It was an intermittent ticking!

No reptile or insect with which I am familiar reproduces any such notes. I lay for an hour—listening intently.

At last my curiosity got the better of me. I arose, lighted my lamp and commenced to investigate.

My bedding lay upon a rug stretched directly upon the warm sand. The noise appeared to be coming from beneath the rug. I raised it, but found nothing—yet, at intervals, the sound continued.

I dug into the sand with the point of my hunting-knife. A few inches below the surface of the sand I encountered a solid substance that had the feel of wood beneath the sharp steel.

Excavating about it, I unearthed a small wooden box. From this receptacle issued the strange sound that I had heard.

How had it come here?

What did it contain?

In attempting to lift it from its burying place I discovered that it seemed to be held fast by means of a very small insulated cable running farther into the sand beneath it.

My first impulse was to drag the thing loose by main strength; but fortunately I thought better of this and fell to examining the box. I soon saw that it was covered by a hinged lid, which was held closed by a simple screwhook and eye.

It took but a moment to loosen this and raise the cover, when, to my utter astonishment, I discovered an ordinary telegraph instrument clicking away within.

"What in the world," thought I, "is this thing doing here?"

That it was a French military instrument was my first guess; but really there didn't seem much likelihood that this was the correct explanation, when one took into account the loneliness and remoteness of the spot.

As I sat gazing at my remarkable find, which was ticking and clicking away there in the silence of the desert night, trying to convey some message which I was unable to interpret, my eyes fell upon a bit of paper lying in the bottom of the box beside the instrument. I picked it up and examined it. Upon it were written but two letters:

D. I.

They meant nothing to me then. I was baffled.

Once, in an interval of silence upon the part of the receiving instrument, I moved the sending-key up and down a few times. Instantly the receiving mechanism commenced to work frantically.

I tried to recall something of the Morse Code, with which I had played as a little boy—but time had obliterated it from my memory. I became almost frantic as I let my imagination run riot among the possibilities for which this clicking instrument might stand.

Some poor devil at the unknown other end might be in dire need of succor. The very franticness of the instrument's wild clashing betokened something of the kind.

And there sat I, powerless to interpret, and so powerless to help!

It was then that the inspiration came to me. In a flash there leaped to my mind the closing paragraphs of the story I had read in the club at Algiers:

Does the answer lie somewhere upon the bosom of the broad Sahara, at the ends of two tiny wires, hidden beneath a lost cairn?

The idea seemed preposterous. Experience and intelligence combined to assure me that there could be no slightest grain of truth or possibility in your wild tale—it was fiction pure and simple.

And yet where WERE the other ends of those wires?

What was this instrument—ticking away here in the great Sahara—but a travesty upon the possible!

Would I have believed in it had I not seen it with my own eyes?

And the initials—D. I.—upon the slip of paper!

David's initials were these—David Innes.

I smiled at my imaginings. I ridiculed the assumption that there was an inner world and that these wires led downward through the earth's crust to the surface of Pellucidar. And yet—

Well, I sat there all night, listening to that tantalizing clicking, now and then moving the sending-key just to let the other end know that the instrument had been discovered. In the morning, after carefully returning the box to its hole and covering it over with sand, I called my servants about me, snatched a hurried breakfast, mounted my horse, and started upon a forced march for Algiers.

I arrived here today. In writing you this letter I feel that I am making a fool of myself.

There is no David Innes.

There is no Dian the Beautiful.

There is no world within a world.

Pellucidar is but a realm of your imagination—nothing more.

BUT—

The incident of the finding of that buried telegraph instrument upon the lonely Sahara is little short of uncanny, in view of your story of the adventures of David Innes.

I have called it one of the most remarkable coincidences in modern fiction. I called it literature before, but—again pardon my candor—your story is not.

And now—why am I writing you?

Heaven knows, unless it is that the persistent clicking of that unfathomable enigma out there in the vast silences of the Sahara has so wrought upon my nerves that reason refuses longer to function sanely.

I cannot hear it now, yet I know that far away to the south, all alone beneath the sands, it is still pounding out its vain, frantic appeal.

It is maddening.

It is your fault—I want you to release me from it.

Cable me at once, at my expense, that there was no basis of fact for your story, At the Earth's Core.

Very respectfully yours,

COGDON NESTOR,—— and —— Club,Algiers.June 1st, —.

Ten minutes after reading this letter I had cabled Mr. Nestor as follows:

Story true. Await me Algiers.

As fast as train and boat would carry me, I sped toward my destination. For all those dragging days my mind was a whirl of mad conjecture, of frantic hope, of numbing fear.

The finding of the telegraph-instrument practically assured me that David Innes had driven Perry's iron mole back through the earth's crust to the buried world of Pellucidar; but what adventures had befallen him since his return?

Had he found Dian the Beautiful, his half-savage mate, safe among his friends, or had Hooja the Sly One succeeded in his nefarious schemes to abduct her?

Did Abner Perry, the lovable old inventor and paleontologist, still live?

Had the federated tribes of Pellucidar succeeded in overthrowing the mighty Mahars, the dominant race of reptilian monsters, and their fierce, gorilla-like soldiery, the savage Sagoths?

I must admit that I was in a state bordering upon nervous prostration when I entered the —— and —— Club, in Algiers, and inquired for Mr. Nestor. A moment later I was ushered into his presence, to find myself clasping hands with the sort of chap that the world holds only too few of.

He was a tall, smooth-faced man of about thirty, clean-cut, straight, and strong, and weather-tanned to the hue of a desert Arab. I liked him immensely from the first, and I hope that after our three months together in the desert country—three months not entirely lacking in adventure—he found that a man may be a writer of "impossible trash" and yet have some redeeming qualities.

The day following my arrival at Algiers we left for the south, Nestor having made all arrangements in advance, guessing, as he naturally did, that I could be coming to Africa for but a single purpose—to hasten at once to the buried telegraph-instrument and wrest its secret from it.

In addition to our native servants, we took along an English telegraph-operator named Frank Downes. Nothing of interest enlivened our journey by rail and caravan till we came to the cluster of date-palms about the ancient well upon the rim of the Sahara.

It was the very spot at which I first had seen David Innes. If he had ever raised a cairn above the telegraph instrument no sign of it remained now. Had it not been for the chance that caused Cogdon Nestor to throw down his sleeping rug directly over the hidden instrument, it might still be clicking there unheard—and this story still unwritten.

When we reached the spot and unearthed the little box the instrument was quiet, nor did repeated attempts upon the part of our telegrapher succeed in winning a response from the other end of the line. After several days of futile endeavor to raise Pellucidar, we had begun to despair. I was as positive that the other end of that little cable protruded through the surface of the inner world as I am that I sit here today in my study—when about midnight of the fourth day I was awakened by the sound of the instrument.

Leaping to my feet I grasped Downes roughly by the neck and dragged him out of his blankets. He didn't need to be told what caused my excitement, for the instant he was awake he, too, heard the long-hoped for click, and with a whoop of delight pounced upon the instrument.

Nestor was on his feet almost as soon as I. The three of us huddled about that little box as if our lives depended upon the message it had for us.

Downes interrupted the clicking with his sending-key. The noise of the receiver stopped instantly.

"Ask who it is, Downes," I directed.

He did so, and while we awaited the Englishman's translation of the reply, I doubt if either Nestor or I breathed.

"He says he's David Innes," said Downes. "He wants to know who we are."

"Tell him," said I; "and that we want to know how he is—and all that has befallen him since I last saw him."

For two months I talked with David Innes almost every day, and as Downes translated, either Nestor or I took notes. From these, arranged in chronological order, I have set down the following account of the further adventures of David Innes at the earth's core, practically in his own words.

Chapter I: Lost On Pellucidar

The Arabs, of whom I wrote you at the end of my last letter (Innes began), and whom I thought to be enemies intent only upon murdering me, proved to be exceedingly friendly—they were searching for the very band of marauders that had threatened my existence. The huge rhamphorhynchus-like reptile that I had brought back with me from the inner world—the ugly Mahar that Hooja the Sly One had substituted for my dear Dian at the moment of my departure—filled them with wonder and with awe.

Nor less so did the mighty subterranean prospector which had carried me to Pellucidar and back again, and which lay out in the desert about two miles from my camp.

With their help I managed to get the unwieldy tons of its great bulk into a vertical position—the nose deep in a hole we had dug in the sand and the rest of it supported by the trunks of date-palms cut for the purpose.

It was a mighty engineering job with only wild Arabs and their wilder mounts to do the work of an electric crane—but finally it was completed, and I was ready for departure.

For some time I hesitated to take the Mahar back with me. She had been docile and quiet ever since she had discovered herself virtually a prisoner aboard the "iron mole." It had been, of course, impossible for me to communicate with her since she had no auditory organs and I no knowledge of her fourth-dimension, sixth-sense method of communication.

Naturally I am kind-hearted, and so I found it beyond me to leave even this hateful and repulsive thing alone in a strange and hostile world. The result was that when I entered the iron mole I took her with me.

That she knew that we were about to return to Pellucidar was evident, for immediately her manner changed from that of habitual gloom that had pervaded her, to an almost human expression of contentment and delight.

Our trip through the earth's crust was but a repetition of my two former journeys between the inner and the outer worlds. This time, however, I imagine that we must have maintained a more nearly perpendicular course, for we accomplished the journey in a few minutes' less time than upon the occasion of my first journey through the five-hundred-mile crust. Just a trifle less than seventy-two hours after our departure into the sands of the Sahara, we broke through the surface of Pellucidar.

Fortune once again favored me by the slightest of margins, for when I opened the door in the prospector's outer jacket I saw that we had missed coming up through the bottom of an ocean by but a few hundred yards.

The aspect of the surrounding country was entirely unfamiliar to me—I had no conception of precisely where I was upon the one hundred and twenty-four million square miles of Pellucidar's vast land surface.

The perpetual midday sun poured down its torrid rays from zenith, as it had done since the beginning of Pellucidarian time—as it would continue to do to the end of it. Before me, across the wide sea, the weird, horizonless seascape folded gently upward to meet the sky until it lost itself to view in the azure depths of distance far above the level of my eyes.

How strange it looked! How vastly different from the flat and puny area of the circumscribed vision of the dweller upon the outer crust!

I was lost. Though I wandered ceaselessly throughout a lifetime, I might never discover the whereabouts of my former friends of this strange and savage world. Never again might I see dear old Perry, nor Ghak the Hairy One, nor Dacor the Strong One, nor that other infinitely precious one—my sweet and noble mate, Dian the Beautiful!

But even so I was glad to tread once more the surface of Pellucidar. Mysterious and terrible, grotesque and savage though she is in many of her aspects, I can not but love her. Her very savagery appealed to me, for it is the savagery of unspoiled Nature.

The magnificence of her tropic beauties enthralled me. Her mighty land areas breathed unfettered freedom.

Her untracked oceans, whispering of virgin wonders unsullied by the eye of man, beckoned me out upon their restless bosoms.

Not for an instant did I regret the world of my nativity. I was in Pellucidar. I was home. And I was content.

As I stood dreaming beside the giant thing that had brought me safely through the earth's crust, my traveling companion, the hideous Mahar, emerged from the interior of the prospector and stood beside me. For a long time she remained motionless.

What thoughts were passing through the convolutions of her reptilian brain?

I do not know.

She was a member of the dominant race of Pellucidar. By a strange freak of evolution her kind had first developed the power of reason in that world of anomalies.

To her, creatures such as I were of a lower order. As Perry had discovered among the writings of her kind in the buried city of Phutra, it was still an open question among the Mahars as to whether man possessed means of intelligent communication or the power of reason.

Her kind believed that in the center of all-pervading solidity there was a single, vast, spherical cavity, which was Pellucidar. This cavity had been left there for the sole purpose of providing a place for the creation and propagation of the Mahar race. Everything within it had been put there for the uses of the Mahar.

I wondered what this particular Mahar might think now. I found pleasure in speculating upon just what the effect had been upon her of passing through the earth's crust, and coming out into a world that one of even less intelligence than the great Mahars could easily see was a different world from her own Pellucidar.

What had she thought of the outer world's tiny sun?

What had been the effect upon her of the moon and myriad stars of the clear African nights?

How had she explained them?

With what sensations of awe must she first have watched the sun moving slowly across the heavens to disappear at last beneath the western horizon, leaving in his wake that which the Mahar had never before witnessed—the darkness of night? For upon Pellucidar there is no night. The stationary sun hangs forever in the center of the Pellucidarian sky—directly overhead.

Then, too, she must have been impressed by the wondrous mechanism of the prospector which had bored its way from world to world and back again. And that it had been driven by a rational being must also have occurred to her.

Too, she had seen me conversing with other men upon the earth's surface. She had seen the arrival of the caravan of books and arms, and ammunition, and the balance of the heterogeneous collection which I had crammed into the cabin of the iron mole for transportation to Pellucidar.

She had seen all these evidences of a civilization and brain-power transcending in scientific achievement anything that her race had produced; nor once had she seen a creature of her own kind.

There could have been but a single deduction in the mind of the Mahar—there were other worlds than Pellucidar, and the gilak was a rational being.

Now the creature at my side was creeping slowly toward the near-by sea. At my hip hung a long-barreled six-shooter—somehow I had been unable to find the same sensation of security in the newfangled automatics that had been perfected since my first departure from the outer world—and in my hand was a heavy express rifle.

I could have shot the Mahar with ease, for I knew intuitively that she was escaping—but I did not.

I felt that if she could return to her own kind with the story of her adventures, the position of the human race within Pellucidar would be advanced immensely at a single stride, for at once man would take his proper place in the considerations of the reptilia.

At the edge of the sea the creature paused and looked back at me. Then she slid sinuously into the surf.

For several minutes I saw no more of her as she luxuriated in the cool depths.

Then a hundred yards from shore she rose and there for another short while she floated upon the surface.

Finally she spread her giant wings, flapped them vigorously a score of times and rose above the blue sea. A single time she circled far aloft—and then straight as an arrow she sped away.

I watched her until the distant haze enveloped her and she had disappeared. I was alone.

My first concern was to discover where within Pellucidar I might be—and in what direction lay the land of the Sarians where Ghak the Hairy One ruled.

But how was I to guess in which direction lay Sari?

And if I set out to search—what then?

Could I find my way back to the prospector with its priceless freight of books, firearms, ammunition, scientific instruments, and still more books—its great library of reference works upon every conceivable branch of applied sciences?

And if I could not, of what value was all this vast storehouse of potential civilization and progress to be to the world of my adoption?

Upon the other hand, if I remained here alone with it, what could I accomplish single-handed?

Nothing.

But where there was no east, no west, no north, no south, no stars, no moon, and only a stationary midday sun, how was I to find my way back to this spot should ever I get out of sight of it?

I didn't know.

For a long time I stood buried in deep thought, when it occurred to me to try out one of the compasses I had brought and ascertain if it remained steadily fixed upon an unvarying pole. I reentered the prospector and fetched a compass without.

Moving a considerable distance from the prospector that the needle might not be influenced by its great bulk of iron and steel I turned the delicate instrument about in every direction.

Always and steadily the needle remained rigidly fixed upon a point straight out to sea, apparently pointing toward a large island some ten or twenty miles distant. This then should be north.

I drew my note-book from my pocket and made a careful topographical sketch of the locality within the range of my vision. Due north lay the island, far out upon the shimmering sea.

The spot I had chosen for my observations was the top of a large, flat boulder which rose six or eight feet above the turf. This spot I called Greenwich. The boulder was the "Royal Observatory."

I had made a start! I cannot tell you what a sense of relief was imparted to me by the simple fact that there was at least one spot within Pellucidar with a familiar name and a place upon a map.

It was with almost childish joy that I made a little circle in my note-book and traced the word Greenwich beside it.

Now I felt I might start out upon my search with some assurance of finding my way back again to the prospector.

I decided that at first I would travel directly south in the hope that I might in that direction find some familiar landmark. It was as good a direction as any. This much at least might be said of it.

Among the many other things I had brought from the outer world were a number of pedometers. I slipped three of these into my pockets with the idea that I might arrive at a more or less accurate mean from the registrations of them all.

On my map I would register so many paces south, so many east, so many west, and so on. When I was ready to return I would then do so by any route that I might choose.

I also strapped a considerable quantity of ammunition across my shoulders, pocketed some matches, and hooked an aluminum fry-pan and a small stew-kettle of the same metal to my belt.

I was ready—ready to go forth and explore a world!

Ready to search a land area of 124,110,000 square miles for my friends, my incomparable mate, and good old Perry!

And so, after locking the door in the outer shell of the prospector, I set out upon my quest. Due south I traveled, across lovely valleys thick-dotted with grazing herds.

Through dense primeval forests I forced my way and up the slopes of mighty mountains searching for a pass to their farther sides.

Ibex and musk-sheep fell before my good old revolver, so that I lacked not for food in the higher altitudes. The forests and the plains gave plentifully of fruits and wild birds, antelope, aurochsen, and elk.