Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

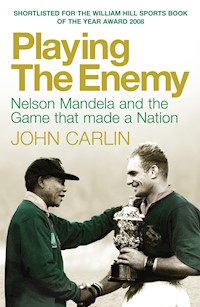

Now filmed as INVICTUS directed by Clint Eastwood, and starring Matt Damon and Morgan Freeman as Nelson Mandela. SHORTLISTED FOR THE WILLIAM HILL SPORTS BOOK OF THE YEAR 2008 As the day of the final of the 1995 Rugby World Cup dawned, and the Springboks faced New Zealand's all-conquering All Blacks, more was at stake than a sporting trophy. When Nelson Mandela appeared wearing a Springboks jersey and led the all-white Afrikaner-dominated team in singing South Africa's new national anthem, he conquered the hearts of white South Africa. Playing the Enemy tells the extraordinary human story of how that moment became possible. It shows how a sport, once the preserve of South Africa's Afrikaans-speaking minority, came to unify the new rainbow nation, and tells of how - just occasionally - something as simple as a game really can help people to rise above themselves and see beyond their differences.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 443

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PLAYING THE ENEMY

ALSO BY JOHN CARLIN

White Angels

PLAYING THE ENEMY

NELSON MANDELA AND THE GAME THAT MADE A NATION

JOHN CARLIN

ATLANTIC BOOKS

LONDON

First published in the United States of America in 2008 by The Penguin Press, an imprint of imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014–3657.

First published in Great Britain in 2008 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © John Carlin, 2008

The moral right of John Carlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 84354 859 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street

FOR MY SON, JAMES NELSON

CONTENTS

Introduction1

Chapter I:Breakfast in Houghton7

Chapter II:The Minister of Justice19

Chapter III:Separate Amenities37

Chapter IV:Bagging the Croc49

Chapter V:Different Planets61

Chapter VI:Ayatollah Mandela75

Chapter VII:The Tiger King93

Chapter VIII:The Mask105

Chapter IX:The Bitter-Enders121

Chapter X:Romancing the General133

Chapter XI:"Address Their Hearts"145

Chapter XII:The Captain and the President159

Chapter XIII:Springbok Serenade171

Chapter XIV:Silvermine183

Chapter XV:Doubting Thomases191

Chapter XVI:The Number Six Jersey201

Chapter XVII:"Nelson! Nelson!"213

Chapter XVIII:Blood in the Throat227

Chapter XIX:

"Don't address their brains.

Address their hearts."

– NELSON MANDELA

PLAYING THE ENEMY

INTRODUCTION

The first person to whom I proposed doing this book was Nelson Mandela. We met in the living room of his home in Johannesburg in August 2001, two years after he'd retired from the South African presidency. After some sunny banter, at which he excels, and some shared reminiscences about the edgy years of political transition in South Africa, on which I had reported for a British newspaper, I made my pitch.

Starting off by laying out the broad themes, I put it to him that all societies everywhere aspire, whether they know it or not, to Utopias of some sort. Politicians trade on people's hopes that heaven on earth is attainable. Since it is not, the lives of nations, like the lives of individuals, are a perpetual struggle in pursuit of dreams. In Mandela's case, the dream that had sustained him during his twenty-seven years in prison was one he shared with Martin Luther King Jr.: that one day people in his country would be judged not by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

As I spoke, Mandela sat inscrutable as a sphinx, as he always does when the conversation turns serious and he is the listener. You're not sure, as you blather on, whether he's paying attention or lost in his own thoughts. But when I quoted King, he nodded with a sharp, lips-pursed, downward jolt of the chin.

Encouraged, I said that the book I meant to write concerned South Africa's peaceful transfer of power from white rule to majority rule, from apartheid to democracy; that the book's span would be ten years, starting with the first political contact he had with the government in 1985 (I got a hint of a nod at that too), while he was still in prison. As for the theme, it was one that would be relevant everywhere conflicts arise from the incomprehension and distrust that goes hand in hand with the species' congenital tribalism. I meant "tribalism" in the widest sense of the word, as applied to race, religion, nationalism, or politics. George Orwell defined it as that "habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good' or ‘bad'." Nowhere since the fall of Nazism had this dehumanizing habit been institutionalized more thoroughly than in South Africa. Mandela himself had described apartheid as a "moral genocide" – not death camps, but the insidious extermination of a people's self-respect.

For that reason, apartheid was the only political system in the world that at the height of the Cold War many countries – the United States, the Soviet Union, Albania, China, France, North Korea, Spain, Cuba – agreed was, by the United Nations definition, "a crime against humanity". Yet from this epic injustice an epic reconciliation arose.

I pointed out to Mandela that in my journalism work I had met many people striving to make peace in the Middle East, in Latin America, in Africa, in Asia: for these people South Africa was an ideal to which they all aspired. In the "conflict resolution" industry, burgeoning since the end of the Cold War, when local conflicts started erupting all over the globe, the handbook for how to achieve peace by political means was South Africa's "negotiated revolution", as someone once called it. No country had ever shepherded itself from tyranny to democracy more ably, and humanely. Much had been written, I acknowledged, about the nuts and bolts of "the South African miracle". But what was missing, to my mind, was a book about the human factor, about the miraculousness of the miracle. I envisioned an unapologetically positive story that displayed the human animal at its best; a book with a flesh-and-blood hero at its centre; a book about a country whose black majority should have been bellowing for revenge but instead, following Mandela's example, gave the world a lesson in enlightened forgiveness. My book would include an ample cast of characters, black and white, whose stories would convey the living face of South Africa's great ceremony of redemption. But also, at a time in history when you looked around the world's leaders and most of those you saw were moral midgets (the sphinx did not flinch at this), my book would be about him. It wouldn't be a biography, but a story that shone a light on his political genius, on the talent he deployed in winning people to his cause through an appeal to their finer qualities; in drawing out, in Abraham Lincoln's phrase, the better angels of their nature.

I said I meant to frame the book around the drama of a particular sporting event. Sport was a powerful mobilizer of mass emotions and shaper of political perceptions. (Another nod, short and sharp.) I gave as examples the Berlin Olympics of 1936, which Hitler used to promote the idea of Aryan superiority, though the black American athlete Jesse Owens upset those plans badly by winning four gold medals; Jackie Robinson, the first black man to play major league baseball, helping set in motion the necessary change of consciousness that would lead to big social changes in America.

I then reminded Mandela of a phrase he had used a year or two earlier when handing over a lifetime achievement award to the Brazilian soccer star Pelé. He had said, and I read from some notes I had brought, "Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire, the power to unite people that little else has…. It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers."

Finally coming to the point, I told Mandela what the narrative heart of my book would be, why it was that I would need his support. I told him that there had been one sporting occasion that outdid all the ones I had just mentioned, one where all the themes I had been touching on during this conversation had converged; one that had evoked magically the "symphony of brotherhood" of Martin Luther King's dreams; one event where all Mandela had striven and suffered for during his life converged. I was referring to the final of the—

Suddenly, his smile lit up the room and, joining his huge hands in happy recognition, he finished the sentence for me: "… the 1995 Rugby World Cup!" My own smile confirmed his guess, and he added, "Yes. Yes. Absolutely! I understand exactly the book you have in mind," he said, in full voice, as if he were not eighty-two but forty years younger. "John, you have my blessing. You have it wholeheartedly."

In high spirits, we shook hands, bade each other farewell, and agreed we'd arrange another meeting soon. ln that second interview, with the tape recorder running, he explained how he had first formed an idea of the political power of sport while in prison; how he had used the 1995 Rugby World Cup as an instrument in the grand strategic purpose he set for himself during his five years as South Africa's first democratically elected president: to reconcile blacks and whites and create the conditions for a lasting peace in a country that barely five years earlier, when he was released from prison, had contained all the conditions for civil war. He told me, often with a chuckle or two, about the trouble he had persuading his own people to back the rugby team, and he spoke with esteem and affection about François Pienaar, the big blond son of apartheid who was the captain of the South African team, the Springboks, and the team manager, another mountainous Afrikaner, Morné du Plessis, whom Mandela described, in a courtly, old-fashioned British way he has, as "an excellent chap".

After Mandela and I spoke that day, all sorts of people agreed to talk to me for the book. I had already accumulated much of the raw material for my story during the six eventful years I worked in South Africa, 1989 to 1995, as bureau chief of the London Independent, and I had been going back to South Africa over the next ten years on journalistic missions. But I started seeing people specifically with this book in mind only after I had talked to Mandela, beginning with a star of that championship Springbok team named Hennie le Roux. You don't expect to emerge feeling warm and sentimental after interviewing a rugby player. But that was what happened to me, because Le Roux had been so moved as he spoke about Mandela and the role he, a decent enough but politically unversed Afrikaner, had found himself playing in his country's national life. We spent about two hours together in an otherwise empty office floor, as dusk fell, and three or four times he had to stop in mid-sentence, choking back sobs.

The interview with Le Roux set the tone for the dozens of others I did for this book. In many cases there was a moment when the eyes of my interlocutor moistened, especially when it was someone from the rugby crowd. And, in all cases – whether it was Archbishop Desmond Tutu, or the far-right Afrikaner nationalist General Constand Viljoen, or his left-leaning twin brother, Braam – they relived the times we discussed in a buoyant mood that bordered at times on euphoria.

More than once people remarked that the book I was going to write felt like a fable, or a parable, or a fairy story. It was a funny thing to say for those who had been the real-life protagonists of a blood-and-guts political tale, but it was true. That it was set in Africa and involved a game of rugby was almost incidental. Had it been set in China and the drama built around a water buffalo race, the tale might have been as enduringly exemplary. For it fulfilled the two basic conditions of a successful fairy story: it was a good yarn and it held a lesson for the ages.

Two other thoughts struck me when I took stock of all the material I had accumulated for this book. First, the political genius of Mandela. Stripped to its essentials, politics is about persuading people, winning them over. All politicians are professional seducers. They woo people for a living. And if they are clever and good at what they do, if they have a talent for striking the popular chord, they will prosper. Lincoln had it, Roosevelt had it, Churchill had it, de Gaulle had it, Kennedy had it, Martin Luther King had it, Reagan had it, Clinton and Blair had it. So did Arafat. And so, for that matter, did Hitler. They all won over their people to their cause. Where Mandela – the anti-Hitler – had an edge over the lot of them, where he was unique, was in the scope of his ambition. Having won over his own people – in itself no mean feat, for they were a disparate bunch, drawn from all manner of creeds, colours, and tribes – he then went out and won over the enemy. How he did that – how he won over people who had applauded his imprisonment, who had wanted him dead, who planned to go to war against him – is chiefly what this book is about.

The second thought I caught myself having was that, beyond a history, beyond even a fairy tale, this might also turn out to be an unwitting addition to the vast canon of self-help books offering people models for how to prosper in their daily lives. Mandela mastered, more than anyone else alive (and, quite possibly, dead), the art of making friends and influencing people. No matter whether they started out on the extreme left or the extreme right, whether they initially feared, hated, or admired Mandela, everyone I interviewed had come to feel renewed and improved by his example. All of them, in talking about him, seemed to shine. This book seeks, humbly, to reflect a little of Mandela's light.

CHAPTER IBREAKFAST IN HOUGHTON

June 24, 1995

He awoke, as he always did, at 4:30 in the morning; he got up, got dressed, folded his pyjamas, and made his bed. All his life he had been a revolutionary, and now he was president of a large country, but nothing would make Nelson Mandela break with the rituals established during his twenty-seven years in prison.

Not when he was at someone else's home, not when he was staying in a luxury hotel, not even after he had spent the night at Buckingham Palace or the White House. Unnaturally unaffected by jet lag – no matter whether he was in Washington, London, or New Delhi – he would wake up unfailingly by 4:30, and then make his bed. Room cleaners the world over would react with stupefaction on discovering that the visiting dignitary had done half their job for them. None more so than the lady assigned to his hotel suite on a visit to Shanghai. She was shocked by Mandela's individualist bedroom manners. Alerted by his staff to the chambermaid's distress, Mandela invited her to his room, apologized, and explained that making his bed was like brushing his teeth, it was something he simply could not restrain himself from doing.

He was similarly wedded to an exercise routine he'd begun even before prison, in the forties and fifties when he was a lawyer, revolutionary, and amateur boxer. In those days he would run for an hour before sunrise, from his small brick home in Soweto to Johannesburg and back. In 1964 he went to prison on Robben Island, off the coast of Cape Town, remaining inside a tiny cell for eighteen years. There, for lack of a better alternative, he would run in place. Every morning, again, for one hour. In 1982 he was transferred to a prison on the mainland where he shared a cell with his closest friend, Walter Sisulu, and three other veterans of South Africa's anti-apartheid struggle. The cell was big, about the size of half a tennis court, allowing him to run short, tight laps. The problem was that the others were still in bed when he would set off on these indoor half-marathons. They used to complain bitterly at being pummelled out of their sleep every morning by their otherwise esteemed comrade's relentlessly vigorous sexagenarian thump-thump.

After his release from prison aged seventy-one, in February 1990, he eased up a little. Instead of running, he now walked, but briskly, and still every morning, still for one hour, before daybreak. These walks usually took place in the neighbourhood of Houghton, Johannesburg, where he moved in April 1992 after the collapse of his marriage to his second wife, Winnie. Two years later he became president and had two grand residences at his disposal, one in Pretoria and one in Cape Town, but he felt more comfortable at his place in Houghton, a refuge in the affluent, and until recently whites-only, northern suburbs of Africa's richest metropolis. An inhabitant of Los Angeles would be struck by the similarities between Beverly Hills and Houghton. The whites had looked after themselves well during Mandela's long absence in jail, and now he felt that he had earned a little of the good life too. He enjoyed Houghton's quiet stateliness, the leafy airiness of his morning walks, the chats with the white neighbours, whose birthday parties and other ceremonial gatherings he would sometimes attend. Early on in his presidency a thirteen-year-old Jewish boy dropped by Mandela's home and handed the policeman at the gate an invitation to his bar mitzvah. The parents were astonished to receive a phone call from Mandela himself a few days later asking for directions to their home. They were even more astonished when he showed up at the door, tall and beaming, on their son's big day. Mandela felt welcomed and comfortable in a community where during most of his life he could only have lived had he been what in white South Africa they used to call, irrespective of age, a "garden boy". He grew fond of Houghton and continued to live there throughout his presidency, sleeping at his official mansions only when duty required it.

On this particular Southern Hemisphere winter's morning Mandela woke at 4:30, as usual, got dressed, and made his bed … but then, behaving in a manner stunningly out of the ordinary for a creature as set in his ways as he was, he broke his routine; he did not go for his morning walk. He went downstairs instead, sat at his chair in the dining room, and ate his breakfast. He had thought through this change of plan the night before, giving him time to inform his startled bodyguards, the Presidential Protection Unit, that the next morning they could have one more hour at home in bed. Instead of arriving at five, they could come at six. They would need the extra rest, for the day would be almost as much of a test for them as it would be for Mandela himself.

Another sign that this was no ordinary day was that Mandela, not usually prone to nerves, had a knot in his stomach. "You don't know what I went through on that day," he confessed to me. "I was so tense!" It was a curious thing for a man with his past to say. This was not the day of his release in February 1990, nor his presidential inauguration in May 1994, nor even the morning back in June 1964 when he woke up in a cell not knowing whether the judge would condemn him to death or, as it turned out, to a life sentence. This was the day on which his country, South Africa, would be playing the best team in the world, New Zealand, in the final of the Rugby World Cup. His compatriots were as tense as he was. But the remarkable thing, in a country that had lurched historically from crisis to disaster, was that the anxiety they all felt concerned the prospect of imminent national triumph.

Before today, when one story dominated the newspapers it almost always meant something bad had happened, or was about to happen; or that it concerned something that one part of the country would interpret as good, another part, as bad. This morning an unheard-of national consensus had formed around one idea. All 43 million South Africans, black and white and all shades in between, shared the same aspiration: victory for their team, the Springboks.

Or almost all. There was at least one malcontent in those final hours before the game, one who wanted South Africa to lose. Justice Bekebeke was his name and contrary, on this day, was his nature. He was sticking by what he regarded as his principled position even though he knew no one who shared his desire that the other team should win. Not his girlfriend, not the rest of his family nor his best friends in Paballelo, the black township where he lived. Everybody he knew was with Mandela and "the Boks", despite the fact that of the fifteen players who would be wearing the green-and-gold South African rugby jersey that afternoon, all would be white except one. And this in a country where almost 90 per cent of the population was black or brown. Bekebeke would have no part of it. He was holding out, refusing to enter into this almost drunken spirit of multiracial fellow-feeling that had so puzzlingly possessed even Mandela, his leader, his hero.

On the face of it, he was right and Mandela and all the others were not only wrong but mad. Rugby was not black South Africa's game. Neither Bekebeke nor Mandela nor the vast majority of their black compatriots had grown up with it or had any particular feel for it. If Mandela, such a big fan suddenly, were to be honest, he would confess that he struggled to grasp a number of the rules. Like Bekebeke, Mandela had spent most of his life actively disliking rugby. It was a white sport, and especially the sport of the Afrikaners, South Africa's dominant white tribe – apartheid's master race. The Springboks had long been seen by black people as a symbol of apartheid oppression as repellent as the old white national anthem and the old white national flag. The revulsion ought to have been even sharper if, like Bekebeke and Mandela, you had spent time in jail for fighting apartheid – in Bekebeke's case, for six of his thirty-four years.

Another character who, for quite different reasons, might have been expected to follow Bekebeke's anti-Springbok line that day was General Constand Viljoen. Viljoen was retired now but he had been head of the South African military during five of the most violent years of confrontation between black activists and the state. He had caused a lot more bloodshed defending apartheid than Bekebeke had done fighting it, yet he never went to jail for what he did. He might have been grateful for that, but instead he had spent part of his retirement mobilizing an army to rise up against the new democratic order. This morning, though, he got out of bed down in Cape Town in the same state of thrilling tension as Mandela and the group of Afrikaner friends with whom he planned to watch the game on TV that afternoon.

Niël Barnard, an Afrikaner with the curious distinction of having fought against both Mandela and Viljoen at different times, was even more tautly wound up than either of his former enemies. Barnard, who was preparing to watch the game with his family at his home in Pretoria, more than nine hundred miles north of Cape Town, forty minutes up the highway from Johannesburg, had been head of South Africa's National Intelligence Service during apartheid's last decade. Closer than any man to the notoriously implacable President P. W. Botha, he was seen as a dark and demonic figure by right and left alike, and by people way beyond South Africa itself. By trade and temperament a defender of the state, whatever form that state might take, he had waged war on Mandela's ANC, had been the brains behind the peace talks with them, and then had defended the new political system against the attacks of the right wing, to which he had originally belonged. He had a reputation for being frighteningly cold and clinical. Yet when he let go, he let go. Rugby was his escape valve. When the Springboks were playing he shed all inhibitions and became, by his own admission, a screaming oaf. Today, when they were going to be playing the biggest game in South African rugby history, he awoke a bag of nerves.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, on the details of whose private life Barnard used to keep dossiers, was in a state of similar nervous apprehension – or he would have have been had it not been for the fact that he was unconscious. Tutu, who had been Mandela's understudy on the global stage during the years of Mandela's imprisonment, was possibly the most excitable – and undoubtedly the most cheerful – of all Nobel Peace Prize winners. There were few things he would have enjoyed more than to have been at the stadium watching the game, but he was away in San Francisco at the time, giving speeches and receiving awards. After some anxious searching he had found a bar the night before where he would be able to watch the game on TV at the crack of dawn, Pacific time. He went to sleep troubled merely by his desperate desire for the Springboks to beat the odds next morning and win.

As for the players themselves, they would have been tense enough had this just been an ordinary World Cup final. But they bore an added burden now. One or two of the bluff sportsmen in the South African fifteen might have allowed a political thought to enter their heads at some point before the World Cup competition began, but not more. They were like other white South African men, who were like most males everywhere in that they thought little about politics, and much about sport. But when Mandela had come to see them a month earlier, the day before the World Cup competition began, the novel thought had gripped them that they had become, literally, political players now. On this morning of the final they understood with daunting clarity that victory against New Zealand might achieve the seemingly impossible: unite a country more polarized by racial division than any other in the world.

François Pienaar, the Springbok captain, woke up with the rest of his team at a luxury hotel in northern Johannesburg, near where Mandela lived, in a state of concentration so deep that he struggled to register where he was. When he went out for a limbering-up, mid-morning run his brain had no notion of where his legs were taking him; he focused exclusively on that afternoon's battle. Rugby is like a giant chess match played at speed, with great violence, and the Springboks would be meeting the grand masters of the sport, New Zealand's All Blacks (their name comes from their entirely black strip), the best team in the world and one of the finest ever seen. Pienaar knew that the All Blacks could beat the Boks nine times out of ten.

The only person with a graver responsibility than the Springbok players that day was Linga Moonsamy, a member of the Presidential Protection Unit. Assigned the job of "number one" PPU bodyguard, he would not be more than a step away from Mandela from the moment he left his home for the game until the moment he returned. Moonsamy, a former guerrilla in Mandela's African National Congress, the ANC, was intensely alive, in his professional capacity, to the physical perils his boss would face that day and, as a former freedom fighter, to the political risk he took.

Grateful for the extra hour of sleep his boss had granted him, Moonsamy drove to Mandela's Houghton home, past the police post at the gates, at six in the morning. Soon the PPU team that would be guarding Mandela that day had arrived, all sixteen of them, half of whom were white former policemen, the other half black ex–freedom fighters like himself. They all gathered in a circle in the front yard, as they did every morning, around a member of the team known as the planning officer who shared information received from the National Intelligence Service about possible threats they should look out for and the details of the route to the stadium, vulnerable points on the journey there. One of the four cars in the PPU detachment then went off to scout the route, Moonsamy staying behind with the others, who took turns checking their weapons, giving Mandela's grey armour-plated Mercedes-Benz a once-over and busying themselves with paperwork. Being formally employed by the police, they always had forms to complete and this was the ideal time to do it. Unless something unexpected happened, and it often did, they would have several hours to kill until the time of departure, ample opportunity for Moonsamy and his colleagues to engage in some serious pregame chitchat.

But Moonsamy, mindful of the special responsibility he had today, for the identity of the number one bodyguard changed from one assignment to the next, was as focused on the day's great task as François Pienaar. Moonsamy, a tall, lithe man, twenty-eight years old, faced his life's greatest challenge today. He had been at the PPU since the day Mandela had become president, and he had accumulated his share of adventures. Mandela insisted on making public appearances in unlikely places (bastions of right-wing rural Afrikanerdom, for instance), and he loved to plunge indiscriminately into crowds for some unfiltered contact with his people. He also liked making unscheduled stops, suddenly announcing to his driver to stop outside a bookshop, say, because he had just remembered a novel he wanted to buy. Without a care for the commotion he would cause, Mandela would saunter into the shop. Once in New York when his limo got stuck in traffic on the way to an important appointment, he got out and headed down Sixth Avenue on foot, to the astonishment and delight of the passers-by. "But, Mr. President, please … !" his bodyguards would beg. To which Mandela would reply, "No, look. You take care of your job, and I'll take care of mine."

The PPU's job today was going to be of a different order from anything they had ever faced before, or would ever face again. That afternoon's game, or Mandela's part in it, was going to be, as Moonsamy saw it, Daniel entering the lion's den – save that there would be 62,000 lions at Ellis Park Stadium, a monument to white supremacy not far from gentle Houghton, and just the one Daniel. Ninety-five per cent of the crowd would be white, mostly Afrikaners. Surrounded by this unlikely host (never had Mandela appeared in front of a crowd like this one), he would emerge onto the field to shake hands with the players before the game, and again at the end to hand the cup to the winning captain.

The scene Moonsamy imagined – the massed ranks of the old enemy, beer-bellied Afrikaners in khaki shirts, encircling the man they had been taught most of their lives to view as South Africa's great terrorist-in-chief – had the quality of a surreal dream. Yet contained within it was Mandela's entirely serious, real-life purpose. His mission, in common with all politically active black South Africans of his generation, had been to replace apartheid with what the ANC called a "nonracial democracy". But he had yet to achieve a goal that was as important, and no less challenging. He was president now. One-person-one-vote elections had taken place for the first time in South African history a year earlier. But the job was not yet done. Mandela had to secure the foundations of the new democracy, he had to make it resistant to the dangerous forces that still lurked. History showed that a revolution as complete as the South African one, in which power switches overnight to a historically rival group, leads to a counterrevolution. There were still plenty of heavily armed, military-trained extremists running around; plenty of far-right Afrikaner "bitter-enders" – South Africa's more organized, more numerous, and more heavily armed variations on America's Ku Klux Klan. White right-wing terrorism was to be expected in such circumstances, as Moonsamy's political readings taught him, and white right-wing terrorism was what Mandela sought most of all as president to avoid.

The way to do that was to bend the white population to his will. Early on in his presidency he glimpsed the possibility that the Rugby World Cup might present him with an opportunity to win their hearts. That was why he had been working strenuously to persuade his own black supporters to abandon the entirely justified prejudice of a lifetime and support the Springboks. That was why he wanted to show the Afrikaners in the stadium today that their team was his team too; that he would share in their triumph or their defeat.

But the plan was fraught with peril. Mandela could be shot or blown up by extremists. Or today's pageant could simply backfire. A bad Springbok defeat would not be helpful. Even worse was the prospect of the Afrikaner fans jeering the new national anthem that black South Africans held so dear, or unfurling the hated old orange, blue, and white flag. The millions watching in the black townships would feel humiliated and outraged, switching their allegiances to the New Zealand team, shattering the consensus Mandela had striven to build around the Springboks, with potentially destabilizing consequences.

But Mandela was an optimist. He believed things would turn out right, just as he believed (here he was in a small minority) that the Springboks would win. That was why it was in a tense but cheerful mood that he sat down on this cold, bright winter's Saturday morning to his habitually big breakfast. He had, in this order: half a papaya, then corn porridge, served stiff, to which he added mixed nuts and raisins before pouring in hot milk; this was followed by a green salad, then – on a side plate – three slices of banana, three slices of kiwifruit, and three slices of mango. Finally he served himself a cup of coffee, which he sweetened with honey.

Mandela, longing for the game to start, ate this morning with special relish. He had not realized it until now, but his whole life had been a preparation for this moment. His decision to join the ANC as a young man in the forties; his defiant leadership in the campaign against apartheid in the fifties; the solitude and toughness and quiet routine of prison; the grinding exercise regimen to which he submitted himself behind bars, believing always that he would get out one day and play a leading role in his country's affairs: all that, and much more, had provided the platform for the final push of the last ten years, a period that had seen Mandela take on his toughest battles and his most unlikely victories. Today was the great test, and the one that offered the prospect of the most enduring reward.

If it worked it would bring to a triumphant conclusion the journey he undertook, classically epic in its ambition, in the final decade of his long walk to freedom. Like Homer's Odysseus, he progressed from challenge to challenge, overcoming each one not because he was stronger than his foes, but because he was cleverer and more beguiling. He had forged these qualities following his arrest and imprisonment in 1962, when he came to realize that the route of brute force he had attempted, as the founding commander of the ANC's military wing, could not work. In jail he judged that the way to kill apartheid was to persuade white people to kill it themselves, to join his team, submit to his leadership.

It was in jail too that he seized his first great chance to put the strategy into action. The adversary on that occasion was a man called Kobie Coetsee, whose state of mind on this morning of the rugby game was one of nerve-shredding excitement, like everybody else's; whose clarity of purpose was clouded only by the question whether he should watch the game at his home, just outside Cape Town, or soak in the atmosphere at a neighbourhood bar. Coetsee and Mandela were on the same side today to a degree that would have been unthinkable when they had first met a decade ago. Back then, they had every reason to feel hostile towards each other. Mandela was South Africa's most celebrated political prisoner; Coetsee was South Africa's minister of justice and of prisons. The task Mandela had set himself back then, twenty-three years into his life sentence, was to win over Coetsee, the man who held the keys to his cell.

CHAPTER IITHE MINISTER OF JUSTICE

November 1985

Nineteen eighty-five was a hopeful year for the world but not for South Africa. Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union, Ronald Reagan was sworn in as president for a second term, and the two Cold War leaders held their first meeting, offering the strongest signal in forty years that the superpowers might prevail upon each other to shelve their stratagems for mutually assured destruction. South Africa was rushing in the opposite direction. Tensions between anti-apartheid militants and the police exploded into the most violent escalation of racial hostilities since Queen Victoria's redcoats and King Cetshwayo's battalions inflicted savage slaughter on each other in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. The exiled ANC leadership stirred their supporters inside South Africa to rise up against the government, but they pursued their offensive against the government across other fronts too. Through the powerful domestic trade unions, through international economic sanctions, through diplomatic isolation. And through rugby. For twenty years, the ANC had been waging a campaign to deprive white male South Africans, and especially the Afrikaners, of international rugby, their lives' great passion. Nineteen eighty-five was the year they secured their greatest triumphs, successfully thwarting a planned Springbok tour of New Zealand. That hurt. The fresh memory of that defeat injected an added vitality into the hammy forearms of the Afrikaner riot police as they thumped their truncheons down on the heads of their black victims.

The only prospect in sight that year, it seemed, was civil war. A national opinion poll conducted in mid-August found that 70 per cent of the black population and 30 per cent of the white believed that was the direction the country was heading in. But were it to come to that, the winner would not be Mandela's ANC; it would be their chief adversary, President P. W. Botha, better known in South Africa as "P.W." or, by the friends and foes who feared him, "die groot krokodil", the big crocodile. Botha, who ruled South Africa between 1978 and 1989, announced a state of emergency in the middle of 1985 and ordered 35,000 troops of the South African Defence Force, better known as the SADF, into the black townships, the first time the military had been called in to help the police quell what the government believed to be an increasingly orchestrated rebellion. Their suspicions were confirmed when the ANC's exiled leadership responded to Botha's move by calling for a "People's War" to make the country "ungovernable", prompting white people to flee the country – to Britain, to Australia, to America – in droves. Nineteen eighty-five was the year in which TV viewers around the world grew accustomed to seeing South Africa as a country of burning barricades where stone-throwing black youths faced up to white policemen with guns, where SADF armoured vehicles advanced like spidery alien craft on angry, frightened black mobs. Under the state of emergency regulations, the security forces were granted practically limitless powers of search, seizure, and arrest – as well as the comfort of knowing that they could assault suspects with impunity. In the fifteen months leading up to the first week of November that year 850 people had died in political violence and thousands had been jailed without charge.

In this climate, in this year, Mandela launched his peace offensive. Convinced that negotiations were the only way that apartheid could ultimately be brought down, he took on the challenge alone and, as it turned out, with one arm tied behind his back. Earlier in the year, doctors had discovered he had prostate problems and, fearing cancer, ruled that he needed urgent surgery. They had made the diagnosis at Pollsmoor Prison, where he'd been transferred from Robben Island three years earlier, in 1982. Pollsmoor, on the mainland near Cape Town, was where he shared the large cell with Walter Sisulu and three other prison veterans whom he would infuriate with his predawn indoor runs. The operation, carried out on November 4, 1985, was a success, but Mandela, now aged sixty-seven, had to remain under observation. Doctors' orders were for him to convalesce in the hospital for three more weeks.

During this interlude, Mandela's first spell outside bars in twenty-three years, he began his ten-year courtship of white South Africa. By a remarkable historical coincidence, this was the very month in which Reagan and Gorbachev met. Just as the American president set out to use his charm on the Soviet leader, Mandela prepared to use his on Kobie Coetsee, the man with the world's most contradictory job description, minister of justice of South Africa.

But while the superpower summit in Geneva was a media circus, this meeting was top secret. The press did not learn of it until five years later, but even if they had known about it at the time, even if the story had been leaked, they would have had trouble finding anyone to believe it. The ANC were the enemy, the purveyors of a Soviet-inspired "Total Onslaught", in P. W. Botha's term, against whom the state's security forces had launched what he called a "Total Strategy". Nothing was more unthinkable than the idea of the Botha regime negotiating with the "Communist terrorists", much less with their jailed leader.

But if anyone in government was to make that first contact with the enemy it was Coetsee, whose portfolio extended beyond justice to include correctional services, meaning the prison system. Botha chose Coetsee to be his secret emissary because he was blindly loyal – one of the few people in his cabinet whom Botha trusted to behave discreetly – and because, as minister of justice and of prisons, he was the appropriate member of his government to go and meet Mandela. Besides, it had been to Coetsee, as to his predecessors in the Justice Ministry, that Mandela had long been addressing letters requesting a meeting. In so doing Mandela had been following in a rather hapless ANC tradition, begun with the organization's founding in 1912, of seeking to persuade white governments to sit down and discuss the country's future together. But now at last it was going to happen: the very first talks between a black politician and a senior member of the white government. Botha's reasons for sanctioning the encounter were partly a matter of curiosity – the ANC had launched a Free Mandela campaign in 1980 and by now he was the most famous, least known prisoner in the world. But Botha was motivated more by the increasingly volatile situation in the townships and the intensifying pressure from the outside world. He felt that the time had come to dip a toe in the waters of reconciliation, to venture the first tentative test of whether one day an accommodation with black South Africa might be possible. As Coetsee would explain it later, "We had painted ourselves into a corner and we had to find a way out."

The curious thing was that while Mandela had been the supplicant, Coetsee was the one who felt uncomfortable. It was a mixture of guilt and fear – guilt because he would be seeing Mandela as the emissary of the government that was killing his people; fear because he had read the files on Mandela and he was uneasy at the prospect of coming face-to-face with an enemy so apparently ruthless. "The picture I had formed of him," he said during an interview in Cape Town some years after he had left government, "was of a leader determined to seize power, given the chance, at whatever cost in human lives." From Mandela's files, Coetsee would also have formed a mental image of an imposing former heavyweight boxer who had had the temerity ten months earlier to humiliate his dour, scowling boss, P. W. Botha, before the entire nation. Botha had publicly offered to free Mandela, but he had issued preconditions. Mandela had to promise to abandon the very "armed struggle" that he himself had set in motion when he founded the ANC's military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), back in 1961; he also had to conduct himself "in such a way that he will not have to be arrested" under the apartheid laws. Mandela replied through a statement read out by his daughter Zindzi at a rally in Soweto. Challenging Botha to renounce violence against black people, Mandela mocked the very idea that he might be set free when, so long as apartheid existed, every black person remained in bondage. "I cannot and will not give any undertaking at a time when I and you, the people, are not free," Mandela's statement said. "Your freedom and mine cannot be separated."

Coetsee had understandable misgivings about the meeting, but the balance was tilted heavily in his favour. Mandela was the prisoner, after all, and Coetsee the jailer; Mandela was thin and weak after his operation and wearing hospital clothes – bathrobe, pyjamas, and slippers – while Coetsee, in ministerial suit and tie, glowed with health. And far more depended on the outcome of the meeting for Mandela than it did for Coetsee. For Mandela it was a life-or-death opportunity that might not be repeated; for Coetsee it was an exploratory encounter, almost an act of curiosity. In Mandela's eyes this was the chance he had sought ever since he embarked in politics four decades earlier to begin a serious conversation about the future direction of the country between black and white South Africa. Of all the challenges to his powers of political seduction that he would subsequently face, none would hold greater risks. For had he failed, had he argued with Coetsee, or had the chemistry been wrong, that might have been the beginning and the end of everything.

Yet the moment Coetsee entered Mandela's hospital room the apprehensions on both sides evaporated. Mandela, a model host smiling grandly, put Coetsee at his ease, and almost immediately, to their quietly contained surprise, prisoner and jailer found themselves chatting amiably. Anybody watching unaware of who they were would have assumed that they knew each other well, in the way that a royal adviser knows his prince, or a lawyer his biggest client. It had partly to do with the fact that Mandela, at six foot one, towered over Coetsee, a small, chirpy fellow with big black-framed glasses and the air of a small-town real estate lawyer. But it had more to do with body language, with the impact Mandela's manner had on people he met. First there was his erect posture. Then there was the way he shook hands. He never stooped, he did not incline his head. All the movement was in the socket of the arm and shoulder. Add to that the massive size of his hand and its leathery texture, and the effect was both regal and intimidating. Or it would have been were it not for Mandela's warm gaze and his big, easy smile.

"He was a natural," Coetsee recalled, sparkling with animation, "and I realized that from the moment I set eyes on him. He was a born leader. And he was affable. He was obviously well liked by the hospital personnel and yet he was respected, even though they knew that he was a prisoner. And he was clearly in command of his surroundings."

Mandela mentioned people in the prison service they knew in common; Coetsee inquired after Mandela's health; they chatted about a chance encounter Coetsee had had with his wife, Winnie, on an airplane a few days earlier. Coetsee was surprised by Mandela's willingness to talk in Afrikaans, his knowledge of Afrikaans history. It was all terribly genteel. But both men knew very well that the significance of the meeting lay not in the words they exchanged, but in those that were left unsaid. The fact that there was no animosity in the encounter was in itself a signal, transmitted and received by both men, that the time had come to explore the possibility of fundamental change in how black and white South Africans related politically to one another. It was, as Coetsee would see it, the beginning of a new exercise, "to talk, rather than to fight".

. . .

The absence of cameras, the anodyne hospital setting, the pyjamas, the inconsequential affability of the chat all disguised the truth that Mandela had pulled off the seemingly impossible feat that the ANC had been striving towards for seventy-three years. How had he done it? Like everyone who is very good at what they do – be they athletes, painters, or violinists – he had worked long and hard to develop his natural talent. Walter Sisulu had spotted the leader in him the first day the two men met, in 1942. Sisulu, six years older than Mandela, was a veteran ANC organizer in Johannesburg; Mandela, twenty-five, had just arrived from the countryside. Mandela was a bumpkin to Sisulu's city slicker, but as he sized up the young man standing tall before him, the canny activist in Sisulu saw something that he could use. "He happened to strike me more than any person I had met," Sisulu said more than half a century after that first encounter. "His demeanour, his warmth … I was looking for people of calibre to fill positions of leadership and he was a godsend to me."

Mandela often joked that had he never met Sisulu, he would have spared himself a lot of complications in life. The truth was that Mandela, whose Xhosa name, Rolihlahla, means "troublemaker", went out of his way to court complication, deploying a gift for striking poses to valuable political effect during the peaceful resistance movement of the 1940s and '50s. Public acts had to be staged that would raise political consciousness and set an example of boldness to the black population at large. Mandela, as the so-called "Volunteer in Chief" of the "Defiance Campaign" of that period, was the first to burn his black man's identity document, known as "the pass book", a humiliating method the apartheid government imposed to ensure black people entered white areas only in order to work. Before burning the document, he chose the time and place with a view to maximum media impact. Photographs of the time show him smiling for the cameras as he broke that cornerstone apartheid law. Within days, thousands of ordinary black people were following suit.

As president of the ANC Youth League in the fifties, he stood out as a uniquely self-confident individual. During a meeting of the ANC's top leadership, a black-tie event at which he showed up in a dapper brown suit, he shocked everyone present by giving a speech in which he predicted that he would be the first black president of South Africa.

There was something of the brash young Muhammad Ali in him – quite apart from the fact that he boxed to stay in shape, a shape he also enjoyed displaying. A number of photographs show him posing for the cameras stripped to the waist in classic boxing stances. In photographs of him in suits, he looks the image of a Hollywood matinee idol. In the fifties, he was already the most visible face of black protest, and he dressed impeccably: the only black man who had his suits cut by the same tailor as South Africa's richest man, the gold and diamond magnate Harry Oppenheimer.