8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

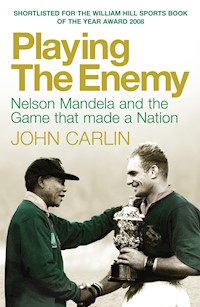

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

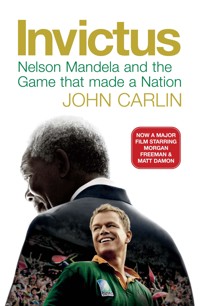

This uplifting true story is now a major film, starring Oscar nominees Morgan Freeman and Matt Damon, directed by Clint Eastwood. Shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year 2008 As the day of the final of the 1995 Rugby World Cup dawned, and the Springboks faced New Zealand's all-conquering All Blacks, more was at stake than a sporting trophy. When Nelson Mandela appeared wearing a Springboks jersey and led the all-white Afrikaner-dominated team in singing South Africa's new national anthem, he conquered the hearts of white South Africa. Invictus tells the extraordinary human story of how that moment became possible. It shows how a sport, once the preserve of South Africa's Afrikaans-speaking minority, came to unify the new rainbow nation, and tells of how - just occasionally - something as simple as a game can help people to rise above themselves and see beyond their differences.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

INVICTUS

John Carlin grew up in Argentina and the UK and spent 1989–95 in South Africa as the Independent’s correspondent there. He has also lived in Nicaragua, Mexico and Washington, writing for The Times, the Observer, the Sunday Times, and the New York Times, among other papers, and working for the BBC. He now lives in Barcelona, where he writes for El Pais.

ALSO BY JOHN CARLIN

White Angels

First published in the United States of America in 2008 by The Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2008, under the title Playing the Enemy, by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This film tie-in paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © John Carlin, 2008

The moral right of John Carlin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 84887 440 4

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I: BREAKFAST IN HOUGHTON

CHAPTER II: THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE

CHAPTER III: SEPARATE AMENITIES

CHAPTER IV: BAGGING THE CROC

CHAPTER V: DIFFERENT PLANETS

CHAPTER VI: AYATOLLAH MANDELA

CHAPTER VII: THE TIGER KING

CHAPTER VIII: THE MASK

CHAPTER IX: THE BITTER-ENDERS

CHAPTER X: ROMANCING THE GENERAL

CHAPTER XI: “ADDRESS THEIR HEARTS”

CHAPTER XII: THE CAPTAIN AND THE PRESIDENT

CHAPTER XIII: SPRINGBOK SERENADE

CHAPTER XIV: SILVERMINE

CHAPTER XV: DOUBTING THOMASES

CHAPTER XVI: THE NUMBER SIX JERSEY

CHAPTER XVII: “NELSON! NELSON!”

CHAPTER XVIII: BLOOD IN THE THROAT

CHAPTER XIX: LOVE THINE ENEMY

EPILOGUE

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A NOTE ON SOURCES

INDEX

“Don’t address their brains.

Address their hearts.”

– NELSON MANDELA

INVICTUS

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll.

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

William Ernest Henley

W E Henley’s classic Victorian inspirational poem, which gave heart to Nelson Mandela during his long prison years.

INTRODUCTION

The first person to whom I proposed doing this book was Nelson Mandela. We met in the living room of his home in Johannesburg in August 2001, two years after he’d retired from the South African presidency. After some sunny banter, at which he excels, and some shared reminiscences about the edgy years of political transition in South Africa, on which I had reported for a British newspaper, I made my pitch.

Starting off by laying out the broad themes, I put it to him that all societies everywhere aspire, whether they know it or not, to Utopias of some sort. Politicians trade on people’s hopes that heaven on earth is attainable. Since it is not, the lives of nations, like the lives of individuals, are a perpetual struggle in pursuit of dreams. In Mandela’s case, the dream that had sustained him during his twenty-seven years in prison was one he shared with Martin Luther King Jr.: that one day people in his country would be judged not by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

As I spoke, Mandela sat inscrutable as a sphinx, as he always does when the conversation turns serious and he is the listener. You’re not sure, as you blather on, whether he’s paying attention or lost in his own thoughts. But when I quoted King, he nodded with a sharp, lips-pursed, downward jolt of the chin.

Encouraged, I said that the book I meant to write concerned South Africa’s peaceful transfer of power from white rule to majority rule, from apartheid to democracy; that the book’s span would be ten years, starting with the first political contact he had with the government in 1985 (I got a hint of a nod at that too), while he was still in prison. As for the theme, it was one that would be relevant everywhere conflicts arise from the incomprehension and distrust that goes hand in hand with the species’ congenital tribalism. I meant “tribalism” in the widest sense of the word, as applied to race, religion, nationalism, or politics. George Orwell defined it as that “habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad’.” Nowhere since the fall of Nazism had this dehumanizing habit been institutionalized more thoroughly than in South Africa. Mandela himself had described apartheid as a “moral genocide” – not death camps, but the insidious extermination of a people’s self-respect.

For that reason, apartheid was the only political system in the world that at the height of the Cold War many countries – the United States, the Soviet Union, Albania, China, France, North Korea, Spain, Cuba – agreed was, by the United Nations definition, “a crime against humanity”. Yet from this epic injustice an epic reconciliation arose.

I pointed out to Mandela that in my journalism work I had met many people striving to make peace in the Middle East, in Latin America, in Africa, in Asia: for these people South Africa was an ideal to which they all aspired. In the “conflict resolution” industry, burgeoning since the end of the Cold War, when local conflicts started erupting all over the globe, the handbook for how to achieve peace by political means was South Africa’s “negotiated revolution”, as someone once called it. No country had ever shepherded itself from tyranny to democracy more ably, and humanely. Much had been written, I acknowledged, about the nuts and bolts of “the South African miracle”. But what was missing, to my mind, was a book about the human factor, about the miraculousness of the miracle. I envisioned an unapologetically positive story that displayed the human animal at its best; a book with a flesh-and-blood hero at its centre; a book about a country whose black majority should have been bellowing for revenge but instead, following Mandela’s example, gave the world a lesson in enlightened forgiveness. My book would include an ample cast of characters, black and white, whose stories would convey the living face of South Africa’s great ceremony of redemption. But also, at a time in history when you looked around the world’s leaders and most of those you saw were moral midgets (the sphinx did not flinch at this), my book would be about him. It wouldn’t be a biography, but a story that shone a light on his political genius, on the talent he deployed in winning people to his cause through an appeal to their finer qualities; in drawing out, in Abraham Lincoln’s phrase, the better angels of their nature.

I said I meant to frame the book around the drama of a particular sporting event. Sport was a powerful mobilizer of mass emotions and shaper of political perceptions. (Another nod, short and sharp.) I gave as examples the Berlin Olympics of 1936, which Hitler used to promote the idea of Aryan superiority, though the black American athlete Jesse Owens upset those plans badly by winning four gold medals; Jackie Robinson, the first black man to play major league baseball, helping set in motion the necessary change of consciousness that would lead to big social changes in America.

I then reminded Mandela of a phrase he had used a year or two earlier when handing over a lifetime achievement award to the Brazilian soccer star Pelé. He had said, and I read from some notes I had brought, “Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire, the power to unite people that little else has. . . . It is more powerful than governments in breaking down racial barriers.”

Finally coming to the point, I told Mandela what the narrative heart of my book would be, why it was that I would need his support. I told him that there had been one sporting occasion that outdid all the ones I had just mentioned, one where all the themes I had been touching on during this conversation had converged; one that had evoked magically the “symphony of brotherhood” of Martin Luther King’s dreams; one event where all Mandela had striven and suffered for during his life converged. I was referring to the final of the—

Suddenly, his smile lit up the room and, joining his huge hands in happy recognition, he finished the sentence for me: “. . . the 1995 Rugby World Cup!” My own smile confirmed his guess, and he added, “Yes. Yes. Absolutely! I understand exactly the book you have in mind,” he said, in full voice, as if he were not eighty-two but forty years younger. “John, you have my blessing. You have it wholeheartedly.”

In high spirits, we shook hands, bade each other farewell, and agreed we’d arrange another meeting soon. In that second interview, with the tape recorder running, he explained how he had first formed an idea of the political power of sport while in prison; how he had used the 1995 Rugby World Cup as an instrument in the grand strategic purpose he set for himself during his five years as South Africa’s first democratically elected president: to reconcile blacks and whites and create the conditions for a lasting peace in a country that barely five years earlier, when he was released from prison, had contained all the conditions for civil war. He told me, often with a chuckle or two, about the trouble he had persuading his own people to back the rugby team, and he spoke with esteem and affection about François Pienaar, the big blond son of apartheid who was the captain of the South African team, the Springboks, and the team manager, another mountainous Afrikaner, Morné du Plessis, whom Mandela described, in a courtly, old-fashioned British way he has, as “an excellent chap”.

After Mandela and I spoke that day, all sorts of people agreed to talk to me for the book. I had already accumulated much of the raw material for my story during the six eventful years I worked in South Africa, 1989 to 1995, as bureau chief of the London Independent, and I had been going back to South Africa over the next ten years on journalistic missions. But I started seeing people specifically with this book in mind only after I had talked to Mandela, beginning with a star of that championship Springbok team named Hennie le Roux. You don’t expect to emerge feeling warm and sentimental after interviewing a rugby player. But that was what happened to me, because Le Roux had been so moved as he spoke about Mandela and the role he, a decent enough but politically unversed Afrikaner, had found himself playing in his country’s national life. We spent about two hours together in an otherwise empty office floor, as dusk fell, and three or four times he had to stop in mid-sentence, choking back sobs.

The interview with Le Roux set the tone for the dozens of others I did for this book. In many cases there was a moment when the eyes of my interlocutor moistened, especially when it was someone from the rugby crowd. And, in all cases – whether it was Archbishop Desmond Tutu, or the far-right Afrikaner nationalist General Constand Viljoen, or his left-leaning twin brother, Braam – they relived the times we discussed in a buoyant mood that bordered at times on euphoria.

More than once people remarked that the book I was going to write felt like a fable, or a parable, or a fairy story. It was a funny thing to say for those who had been the real-life protagonists of a blood-and-guts political tale, but it was true. That it was set in Africa and involved a game of rugby was almost incidental. Had it been set in China and the drama built around a water buffalo race, the tale might have been as enduringly exemplary. For it fulfilled the two basic conditions of a successful fairy story: it was a good yarn and it held a lesson for the ages.

Two other thoughts struck me when I took stock of all the material I had accumulated for this book. First, the political genius of Mandela. Stripped to its essentials, politics is about persuading people, winning them over. All politicians are professional seducers. They woo people for a living. And if they are clever and good at what they do, if they have a talent for striking the popular chord, they will prosper. Lincoln had it, Roosevelt had it, Churchill had it, de Gaulle had it, Kennedy had it, Martin Luther King had it, Reagan had it, Clinton and Blair had it. So did Arafat. And so, for that matter, did Hitler. They all won over their people to their cause. Where Mandela – the anti-Hitler – had an edge over the lot of them, where he was unique, was in the scope of his ambition. Having won over his own people – in itself no mean feat, for they were a disparate bunch, drawn from all manner of creeds, colours, and tribes – he then went out and won over the enemy. How he did that – how he won over people who had applauded his imprisonment, who had wanted him dead, who planned to go to war against him – is chiefly what this book is about.

The second thought I caught myself having was that, beyond a history, beyond even a fairy tale, this might also turn out to be an unwitting addition to the vast canon of self-help books offering people models for how to prosper in their daily lives. Mandela mastered, more than anyone else alive (and, quite possibly, dead), the art of making friends and influencing people. No matter whether they started out on the extreme left or the extreme right, whether they initially feared, hated, or admired Mandela, everyone I interviewed had come to feel renewed and improved by his example. All of them, in talking about him, seemed to shine. This book seeks, humbly, to reflect a little of Mandela’s light.

CHAPTER I

BREAKFAST IN HOUGHTON

June 24, 1995

He awoke, as he always did, at 4:30 in the morning; he got up, got dressed, folded his pyjamas, and made his bed. All his life he had been a revolutionary, and now he was president of a large country, but nothing would make Nelson Mandela break with the rituals established during his twenty-seven years in prison.

Not when he was at someone else’s home, not when he was staying in a luxury hotel, not even after he had spent the night at Buckingham Palace or the White House. Unnaturally unaffected by jet lag – no matter whether he was in Washington, London, or New Delhi – he would wake up unfailingly by 4:30, and then make his bed. Room cleaners the world over would react with stupefaction on discovering that the visiting dignitary had done half their job for them. None more so than the lady assigned to his hotel suite on a visit to Shanghai. She was shocked by Mandela’s individualist bedroom manners. Alerted by his staff to the chambermaid’s distress, Mandela invited her to his room, apologized, and explained that making his bed was like brushing his teeth, it was something he simply could not restrain himself from doing.

He was similarly wedded to an exercise routine he’d begun even before prison, in the forties and fifties when he was a lawyer, revolutionary, and amateur boxer. In those days he would run for an hour before sunrise, from his small brick home in Soweto to Johannesburg and back. In 1964 he went to prison on Robben Island, off the coast of Cape Town, remaining inside a tiny cell for eighteen years. There, for lack of a better alternative, he would run in place. Every morning, again, for one hour. In 1982 he was transferred to a prison on the mainland where he shared a cell with his closest friend, Walter Sisulu, and three other veterans of South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle. The cell was big, about the size of half a tennis court, allowing him to run short, tight laps. The problem was that the others were still in bed when he would set off on these indoor half-marathons. They used to complain bitterly at being pummelled out of their sleep every morning by their otherwise esteemed comrade’s relentlessly vigorous sexagenarian thump-thump.

After his release from prison aged seventy-one, in February 1990, he eased up a little. Instead of running, he now walked, but briskly, and still every morning, still for one hour, before daybreak. These walks usually took place in the neighbourhood of Houghton, Johannesburg, where he moved in April 1992 after the collapse of his marriage to his second wife, Winnie. Two years later he became president and had two grand residences at his disposal, one in Pretoria and one in Cape Town, but he felt more comfortable at his place in Houghton, a refuge in the affluent, and until recently whites-only, northern suburbs of Africa’s richest metropolis. An inhabitant of Los Angeles would be struck by the similarities between Beverly Hills and Houghton. The whites had looked after themselves well during Mandela’s long absence in jail, and now he felt that he had earned a little of the good life too. He enjoyed Houghton’s quiet stateliness, the leafy airiness of his morning walks, the chats with the white neighbours, whose birthday parties and other ceremonial gatherings he would sometimes attend. Early on in his presidency a thirteen-year-old Jewish boy dropped by Mandela’s home and handed the policeman at the gate an invitation to his bar mitzvah. The parents were astonished to receive a phone call from Mandela himself a few days later asking for directions to their home. They were even more astonished when he showed up at the door, tall and beaming, on their son’s big day. Mandela felt welcomed and comfortable in a community where during most of his life he could only have lived had he been what in white South Africa they used to call, irrespective of age, a “garden boy”. He grew fond of Houghton and continued to live there throughout his presidency, sleeping at his official mansions only when duty required it.

On this particular Southern Hemisphere winter’s morning Mandela woke at 4:30, as usual, got dressed, and made his bed . . . but then, behaving in a manner stunningly out of the ordinary for a creature as set in his ways as he was, he broke his routine; he did not go for his morning walk. He went downstairs instead, sat at his chair in the dining room, and ate his breakfast. He had thought through this change of plan the night before, giving him time to inform his startled bodyguards, the Presidential Protection Unit, that the next morning they could have one more hour at home in bed. Instead of arriving at five, they could come at six. They would need the extra rest, for the day would be almost as much of a test for them as it would be for Mandela himself.

Another sign that this was no ordinary day was that Mandela, not usually prone to nerves, had a knot in his stomach. “You don’t know what I went through on that day,” he confessed to me. “I was so tense!” It was a curious thing for a man with his past to say. This was not the day of his release in February 1990, nor his presidential inauguration in May 1994, nor even the morning back in June 1964 when he woke up in a cell not knowing whether the judge would condemn him to death or, as it turned out, to a life sentence. This was the day on which his country, South Africa, would be playing the best team in the world, New Zealand, in the final of the Rugby World Cup. His compatriots were as tense as he was. But the remarkable thing, in a country that had lurched historically from crisis to disaster, was that the anxiety they all felt concerned the prospect of imminent national triumph.

Before today, when one story dominated the newspapers it almost always meant something bad had happened, or was about to happen; or that it concerned something that one part of the country would interpret as good, another part, as bad. This morning an unheard-of national consensus had formed around one idea. All 43 million South Africans, black and white and all shades in between, shared the same aspiration: victory for their team, the Springboks.

Or almost all. There was at least one malcontent in those final hours before the game, one who wanted South Africa to lose. Justice Bekebeke was his name and contrary, on this day, was his nature. He was sticking by what he regarded as his principled position even though he knew no one who shared his desire that the other team should win. Not his girlfriend, not the rest of his family nor his best friends in Paballelo, the black township where he lived. Everybody he knew was with Mandela and “the Boks”, despite the fact that of the fifteen players who would be wearing the green-and-gold South African rugby jersey that afternoon, all would be white except one. And this in a country where almost 90 per cent of the population was black or brown. Bekebeke would have no part of it. He was holding out, refusing to enter into this almost drunken spirit of multiracial fellow-feeling that had so puzzlingly possessed even Mandela, his leader, his hero.

On the face of it, he was right and Mandela and all the others were not only wrong but mad. Rugby was not black South Africa’s game. Neither Bekebeke nor Mandela nor the vast majority of their black compatriots had grown up with it or had any particular feel for it. If Mandela, such a big fan suddenly, were to be honest, he would confess that he struggled to grasp a number of the rules. Like Bekebeke, Mandela had spent most of his life actively disliking rugby. It was a white sport, and especially the sport of the Afrikaners, South Africa’s dominant white tribe – apartheid’s master race. The Springboks had long been seen by black people as a symbol of apartheid oppression as repellent as the old white national anthem and the old white national flag. The revulsion ought to have been even sharper if, like Bekebeke and Mandela, you had spent time in jail for fighting apartheid – in Bekebeke’s case, for six of his thirty-four years.

Another character who, for quite different reasons, might have been expected to follow Bekebeke’s anti-Springbok line that day was General Constand Viljoen. Viljoen was retired now but he had been head of the South African military during five of the most violent years of confrontation between black activists and the state. He had caused a lot more bloodshed defending apartheid than Bekebeke had done fighting it, yet he never went to jail for what he did. He might have been grateful for that, but instead he had spent part of his retirement mobilizing an army to rise up against the new democratic order. This morning, though, he got out of bed down in Cape Town in the same state of thrilling tension as Mandela and the group of Afrikaner friends with whom he planned to watch the game on TV that afternoon.

Niël Barnard, an Afrikaner with the curious distinction of having fought against both Mandela and Viljoen at different times, was even more tautly wound up than either of his former enemies. Barnard, who was preparing to watch the game with his family at his home in Pretoria, more than nine hundred miles north of Cape Town, forty minutes up the highway from Johannesburg, had been head of South Africa’s National Intelligence Service during apartheid’s last decade. Closer than any man to the notoriously implacable President P. W. Botha, he was seen as a dark and demonic figure by right and left alike, and by people way beyond South Africa itself. By trade and temperament a defender of the state, whatever form that state might take, he had waged war on Mandela’s ANC, had been the brains behind the peace talks with them, and then had defended the new political system against the attacks of the right wing, to which he had originally belonged. He had a reputation for being frighteningly cold and clinical. Yet when he let go, he let go. Rugby was his escape valve. When the Springboks were playing he shed all inhibitions and became, by his own admission, a screaming oaf. Today, when they were going to be playing the biggest game in South African rugby history, he awoke a bag of nerves.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, on the details of whose private life Barnard used to keep dossiers, was in a state of similar nervous apprehension – or he would have have been had it not been for the fact that he was unconscious. Tutu, who had been Mandela’s understudy on the global stage during the years of Mandela’s imprisonment, was possibly the most excitable – and undoubtedly the most cheerful – of all Nobel Peace Prize winners. There were few things he would have enjoyed more than to have been at the stadium watching the game, but he was away in San Francisco at the time, giving speeches and receiving awards. After some anxious searching he had found a bar the night before where he would be able to watch the game on TV at the crack of dawn, Pacific time. He went to sleep troubled merely by his desperate desire for the Springboks to beat the odds next morning and win.

As for the players themselves, they would have been tense enough had this just been an ordinary World Cup final. But they bore an added burden now. One or two of the bluff sportsmen in the South African fifteen might have allowed a political thought to enter their heads at some point before the World Cup competition began, but not more. They were like other white South African men, who were like most males everywhere in that they thought little about politics, and much about sport. But when Mandela had come to see them a month earlier, the day before the World Cup competition began, the novel thought had gripped them that they had become, literally, political players now. On this morning of the final they understood with daunting clarity that victory against New Zealand might achieve the seemingly impossible: unite a country more polarized by racial division than any other in the world.

François Pienaar, the Springbok captain, woke up with the rest of his team at a luxury hotel in northern Johannesburg, near where Mandela lived, in a state of concentration so deep that he struggled to register where he was. When he went out for a limbering-up, mid-morning run his brain had no notion of where his legs were taking him; he focused exclusively on that afternoon’s battle. Rugby is like a giant chess match played at speed, with great violence, and the Springboks would be meeting the grand masters of the sport, New Zealand’s All Blacks (their name comes from their entirely black strip), the best team in the world and one of the finest ever seen. Pienaar knew that the All Blacks could beat the Boks nine times out of ten.

The only person with a graver responsibility than the Springbok players that day was Linga Moonsamy, a member of the Presidential Protection Unit. Assigned the job of “number one” PPU bodyguard, he would not be more than a step away from Mandela from the moment he left his home for the game until the moment he returned. Moonsamy, a former guerrilla in Mandela’s African National Congress, the ANC, was intensely alive, in his professional capacity, to the physical perils his boss would face that day and, as a former freedom fighter, to the political risk he took.

Grateful for the extra hour of sleep his boss had granted him, Moonsamy drove to Mandela’s Houghton home, past the police post at the gates, at six in the morning. Soon the PPU team that would be guarding Mandela that day had arrived, all sixteen of them, half of whom were white former policemen, the other half black ex–freedom fighters like himself. They all gathered in a circle in the front yard, as they did every morning, around a member of the team known as the planning officer who shared information received from the National Intelligence Service about possible threats they should look out for and the details of the route to the stadium, vulnerable points on the journey there. One of the four cars in the PPU detachment then went off to scout the route, Moonsamy staying behind with the others, who took turns checking their weapons, giving Mandela’s grey armour-plated Mercedes-Benz a once-over and busying themselves with paperwork. Being formally employed by the police, they always had forms to complete and this was the ideal time to do it. Unless something unexpected happened, and it often did, they would have several hours to kill until the time of departure, ample opportunity for Moonsamy and his colleagues to engage in some serious pregame chitchat.

But Moonsamy, mindful of the special responsibility he had today, for the identity of the number one bodyguard changed from one assignment to the next, was as focused on the day’s great task as François Pienaar. Moonsamy, a tall, lithe man, twenty-eight years old, faced his life’s greatest challenge today. He had been at the PPU since the day Mandela had become president, and he had accumulated his share of adventures. Mandela insisted on making public appearances in unlikely places (bastions of right-wing rural Afrikanerdom, for instance), and he loved to plunge indiscriminately into crowds for some unfiltered contact with his people. He also liked making unscheduled stops, suddenly announcing to his driver to stop outside a bookshop, say, because he had just remembered a novel he wanted to buy. Without a care for the commotion he would cause, Mandela would saunter into the shop. Once in New York when his limo got stuck in traffic on the way to an important appointment, he got out and headed down Sixth Avenue on foot, to the astonishment and delight of the passers-by. “But, Mr. President, please . . . !” his bodyguards would beg. To which Mandela would reply, “No, look. You take care of your job, and I’ll take care of mine.”

The PPU’s job today was going to be of a different order from anything they had ever faced before, or would ever face again. That afternoon’s game, or Mandela’s part in it, was going to be, as Moonsamy saw it, Daniel entering the lion’s den – save that there would be 62,000 lions at Ellis Park Stadium, a monument to white supremacy not far from gentle Houghton, and just the one Daniel. Ninety-five per cent of the crowd would be white, mostly Afrikaners. Surrounded by this unlikely host (never had Mandela appeared in front of a crowd like this one), he would emerge onto the field to shake hands with the players before the game, and again at the end to hand the cup to the winning captain.

The scene Moonsamy imagined – the massed ranks of the old enemy, beer-bellied Afrikaners in khaki shirts, encircling the man they had been taught most of their lives to view as South Africa’s great terrorist-in-chief – had the quality of a surreal dream. Yet contained within it was Mandela’s entirely serious, real-life purpose. His mission, in common with all politically active black South Africans of his generation, had been to replace apartheid with what the ANC called a “nonracial democracy”. But he had yet to achieve a goal that was as important, and no less challenging. He was president now. One-person-one-vote elections had taken place for the first time in South African history a year earlier. But the job was not yet done. Mandela had to secure the foundations of the new democracy, he had to make it resistant to the dangerous forces that still lurked. History showed that a revolution as complete as the South African one, in which power switches overnight to a historically rival group, leads to a counterrevolution. There were still plenty of heavily armed, military-trained extremists running around; plenty of far-right Afrikaner “bitter-enders” – South Africa’s more organized, more numerous, and more heavily armed variations on America’s Ku Klux Klan. White right-wing terrorism was to be expected in such circumstances, as Moonsamy’s political readings taught him, and white right-wing terrorism was what Mandela sought most of all as president to avoid.

The way to do that was to bend the white population to his will. Early on in his presidency he glimpsed the possibility that the Rugby World Cup might present him with an opportunity to win their hearts. That was why he had been working strenuously to persuade his own black supporters to abandon the entirely justified prejudice of a lifetime and support the Springboks. That was why he wanted to show the Afrikaners in the stadium today that their team was his team too; that he would share in their triumph or their defeat.

But the plan was fraught with peril. Mandela could be shot or blown up by extremists. Or today’s pageant could simply backfire. A bad Springbok defeat would not be helpful. Even worse was the prospect of the Afrikaner fans jeering the new national anthem that black South Africans held so dear, or unfurling the hated old orange, blue, and white flag. The millions watching in the black townships would feel humiliated and outraged, switching their allegiances to the New Zealand team, shattering the consensus Mandela had striven to build around the Springboks, with potentially destabilizing consequences.

But Mandela was an optimist. He believed things would turn out right, just as he believed (here he was in a small minority) that the Springboks would win. That was why it was in a tense but cheerful mood that he sat down on this cold, bright winter’s Saturday morning to his habitually big breakfast. He had, in this order: half a papaya, then corn porridge, served stiff, to which he added mixed nuts and raisins before pouring in hot milk; this was followed by a green salad, then – on a side plate – three slices of banana, three slices of kiwifruit, and three slices of mango. Finally he served himself a cup of coffee, which he sweetened with honey.

Mandela, longing for the game to start, ate this morning with special relish. He had not realized it until now, but his whole life had been a preparation for this moment. His decision to join the ANC as a young man in the forties; his defiant leadership in the campaign against apartheid in the fifties; the solitude and toughness and quiet routine of prison; the grinding exercise regimen to which he submitted himself behind bars, believing always that he would get out one day and play a leading role in his country’s affairs: all that, and much more, had provided the platform for the final push of the last ten years, a period that had seen Mandela take on his toughest battles and his most unlikely victories. Today was the great test, and the one that offered the prospect of the most enduring reward.

If it worked it would bring to a triumphant conclusion the journey he undertook, classically epic in its ambition, in the final decade of his long walk to freedom. Like Homer’s Odysseus, he progressed from challenge to challenge, overcoming each one not because he was stronger than his foes, but because he was cleverer and more beguiling. He had forged these qualities following his arrest and imprisonment in 1962, when he came to realize that the route of brute force he had attempted, as the founding commander of the ANC’s military wing, could not work. In jail he judged that the way to kill apartheid was to persuade white people to kill it themselves, to join his team, submit to his leadership.

It was in jail too that he seized his first great chance to put the strategy into action. The adversary on that occasion was a man called Kobie Coetsee, whose state of mind on this morning of the rugby game was one of nerve-shredding excitement, like everybody else’s; whose clarity of purpose was clouded only by the question whether he should watch the game at his home, just outside Cape Town, or soak in the atmosphere at a neighbourhood bar. Coetsee and Mandela were on the same side today to a degree that would have been unthinkable when they had first met a decade ago. Back then, they had every reason to feel hostile towards each other. Mandela was South Africa’s most celebrated political prisoner; Coetsee was South Africa’s minister of justice and of prisons. The task Mandela had set himself back then, twenty-three years into his life sentence, was to win over Coetsee, the man who held the keys to his cell.

CHAPTER II

THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE

November 1985

Nineteen eighty-five was a hopeful year for the world but not for South Africa. Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union, Ronald Reagan was sworn in as president for a second term, and the two Cold War leaders held their first meeting, offering the strongest signal in forty years that the superpowers might prevail upon each other to shelve their stratagems for mutually assured destruction. South Africa was rushing in the opposite direction. Tensions between anti-apartheid militants and the police exploded into the most violent escalation of racial hostilities since Queen Victoria’s redcoats and King Cetshwayo’s battalions inflicted savage slaughter on each other in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. The exiled ANC leadership stirred their supporters inside South Africa to rise up against the government, but they pursued their offensive against the government across other fronts too. Through the powerful domestic trade unions, through international economic sanctions, through diplomatic isolation. And through rugby. For twenty years, the ANC had been waging a campaign to deprive white male South Africans, and especially the Afrikaners, of international rugby, their lives’ great passion. Nineteen eighty-five was the year they secured their greatest triumphs, successfully thwarting a planned Springbok tour of New Zealand. That hurt. The fresh memory of that defeat injected an added vitality into the hammy forearms of the Afrikaner riot police as they thumped their truncheons down on the heads of their black victims.