2,99 €

2,99 €

-100%

Sammeln Sie Punkte in unserem Gutscheinprogramm und kaufen Sie E-Books und Hörbücher mit bis zu 100% Rabatt.

Mehr erfahren.

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

The Americans, of all nations at any time upon the earth, have probably the fullest poetical Nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem. In the history of the earth hitherto the largest and most stirring appear tame and orderly to their ampler largeness and stir. Here at last is something in the doings of man that corresponds with the broadcast doings of the day and night. Here is not merely a nation, but a teeming nation of nations. Here is action untied from strings, necessarily blind to particulars and details, magnificently moving in vast masses.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 304

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

0,0

Bewertungen werden von Nutzern von Legimi sowie anderen Partner-Webseiten vergeben.

Legimi prüft nicht, ob Rezensionen von Nutzern stammen, die den betreffenden Titel tatsächlich gekauft oder gelesen/gehört haben. Wir entfernen aber gefälschte Rezensionen.

Ähnliche

Poems By Walt Whitman

Poems By Walt WhitmanTO WILLIAM BELL SCOTT.PREFATORY NOTICE.PREFACE TO LEAVES OF GRASS.CHANTS DEMOCRATIC.STARTING FROM PAUMANOK.AMERICAN FEUILLAGE.THE PAST-PRESENT.YEARS OF THE UNPERFORMED.FLUX.TO WORKING MEN.SONG OF THE BROAD-AXE.ANTECEDENTS.SALUT AU MONDE!A BROADWAY PAGEANT.OLD IRELAND.BOSTON TOWN.FRANCE, THE EIGHTEENTH YEAR OF THESE STATES.EUROPE, THE SEVENTY-SECOND AND SEVENTY-THIRD YEARS OF THESE STATES.TO A FOILED REVOLTER OR REVOLTRESS.DRUM TAPS.MANHATTAN ARMING.THE UPRISING.BEAT! BEAT! DRUMS!SONG OF THE BANNER AT DAYBREAK.THE BIVOUAC'S FLAME.BIVOUAC ON A MOUNTAIN-SIDE.CITY OF SHIPS.VIGIL ON THE FIELD.THE FLAG.THE WOUNDED.A SIGHT IN CAMP.A GRAVE.THE DRESSER.A LETTER FROM CAMP.WAR DREAMS.THE VETERAN'S VISION.O TAN-FACED PRAIRIE BOY.MANHATTAN FACES.OVER THE CARNAGE.THE MOTHER OF ALL.CAMPS OF GREEN.DIRGE FOR TWO VETERANS.SURVIVORS.HYMN OF DEAD SOLDIERS.SPIRIT WHOSE WORK IS DONE.RECONCILIATION.AFTER THE WAR.WALT WHITMANASSIMILATIONS.A WORD OUT OF THE SEA.CROSSING BROOKLYN FERRY.NIGHT AND DEATH.ELEMENTAL DRIFTS.WONDERS.MIRACLES.VISAGES.THE DARK SIDE.MUSIC.WHEREFORE?ANSWERQUESTIONABLE.SONG AT SUNSET.LONGINGS FOR HOME.APPEARANCES.THE FRIEND.MEETING AGAIN.A DREAM.PARTING FRIENDS.TO A STRANGER.OTHER LANDS.ENVY.THE CITY OF FRIENDS.OUT OF THE CROWD.AMONG THE MULTITUDE.LEAVES OF GRASS.PRESIDENT LINCOLN'S FUNERAL HYMN.O CAPTAIN! MY CAPTAIN!PIONEERS! O PIONEERS!TO THE SAYERS OF WORDS.VOICES.WHOSOEVER.BEGINNERS.TO A PUPIL.LINKS.THE WATERS.TO THE STATES.TEARS.A SHIP.GREATNESS.THE POET.BURIAL.THIS COMPOST.DESPAIRING CRIES.THE CITY DEAD-HOUSETO ONE SHORTLY TO DIE.UNNAMED LANDS.SIMILITUDE.THE SQUARE DEIFIC.GOD.SAVIOUR.SATAN.THE SPIRIT.SONGS OF PARTING.SINGERS AND POETS.TO A HISTORIAN.FIT AUDIENCE.SINGING IN SPRING.LOVE OF COMRADES.PULSE OF MY LIFE.AUXILIARIES.REALITIES.NEARING DEPARTURE.POETS TO COME.CENTURIES HENCE.SO LONG!POSTSCRIPT.NotesCopyrightPoems By Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman

TO WILLIAM BELL SCOTT.

DEAR SCOTT,—Among various gifts which I have received from

you, tangible and intangible, was a copy of the original quarto

edition of Whitman'sLeaves of Grass, which you presented to me soon after its first appearance

in 1855. At a time when few people on this side of the Atlantic had

looked into the book, and still fewer had found in it anything save

matter for ridicule, you had appraised it, and seen that its value

was real and great. A true poet and a strong thinker like yourself

was indeed likely to see that. I read the book eagerly, and

perceived that its substantiality and power were still ahead of any

eulogium with which it might have come commended to me—and, in

fact, ahead of most attempts that could be made at verbal

definition of them.Some years afterwards, getting to know our friend Swinburne,

I found with much satisfaction that he also was an ardent (not of

course ablind) admirer of

Whitman. Satisfaction, and a degree almost of surprise; for his

intense sense of poetic refinement of form in his own works and his

exacting acuteness as a critic might have seemed likely to carry

him away from Whitman in sympathy at least, if not in actual

latitude of perception. Those who find the American poet "utterly

formless," "intolerably rough and floundering," "destitute of the A

B C of art," and the like, might not unprofitably ponder this very

different estimate of him by the author ofAtalanta in Calydon.May we hope that now, twelve years after the first appearance

ofLeaves of Grass, the English

reading public may be prepared for a selection of Whitman's poems,

and soon hereafter for a complete edition of them? I trust this may

prove to be the case. At any rate, it has been a great

gratification to me to be concerned in the experiment; and this is

enhanced by my being enabled to associate with it your name, as

that of an early and well-qualified appreciator of Whitman, and no

less as that of a dear friend.Yours affectionately,W. M. ROSSETTI.

PREFATORY NOTICE.

During the summer of 1867 I had the opportunity (which I had

often wished for) of expressing in print my estimate and admiration

of the works of the American poet Walt Whitman.[1] Like a stone

dropped into a pond, an article of that sort may spread out its

concentric circles of consequences. One of these is the invitation

which I have received to edit a selection from Whitman's writings;

virtually the first sample of his work ever published in England,

and offering the first tolerably fair chance he has had of making

his way with English readers on his own showing. Hitherto, such

readers—except the small percentage of them to whom it has happened

to come across the poems in some one of their American

editions—have picked acquaintance with them only through the medium

of newspaper extracts and criticisms, mostly short-sighted,

sneering, and depreciatory, and rather intercepting than forwarding

the candid construction which people might be willing to put upon

the poems, alike in their beauties and their aberrations. Some

English critics, no doubt, have been more discerning—as W. J. Fox,

of old, in theDispatch, the

writer of the notice in theLeader, and of late two in thePall Mall

Gazetteand theLondon

Review;[2] but these have been the exceptions

among us, the great majority of the reviewers presenting that happy

and familiar critical combination— scurrility and

superciliousness.[Footnote 1: SeeThe Chroniclefor 6th July 1867, articleWalt

Whitman'sPoems.][Footnote 2: Since this Prefatory Notice was written [in

1868], another eulogistic review of Whitman has appeared—that by

Mr. Robert Buchanan, in theBroadway.]As it was my lot to set down so recently several of the

considerations which seem to me most essential and most obvious in

regard to Whitman's writings, I can scarcely now recur to the

subject without either repeating something of what I then said, or

else leaving unstated some points of principal importance. I shall

therefore adopt the simplest course—that of summarising the

critical remarks in my former article; after which, I shall leave

without further development (ample as is the amount of development

most of them would claim) the particular topics there glanced at,

and shall proceed to some other phases of the subject.Whitman republished in 1867 his complete poetical works in

one moderate- sized volume, consisting of the wholeLeaves of Grass, with a sort of

supplement thereto namedSongs before

Parting,[3] and of theDrum

Taps, with itsSequel. It has been intimated that he

does not expect to write any more poems, unless it might be in

expression of the religious side of man's nature. However, one poem

on the last American harvest sown and reaped by those who had been

soldiers in the great war, has already appeared since the volume in

question, and has been republished in England.[Footnote 3: In a copy of the book revised by Whitman

himself, which we have seen, this title is modified intoSongs of Parting.]Whitman's poems present no trace of rhyme, save in a couple

or so of chance instances. Parts of them, indeed, may be regarded

as a warp of prose amid the weft of poetry, such as Shakespeare

furnishes the precedent for in drama. Still there is a very

powerful and majestic rhythmical sense throughout.Lavish and persistent has been the abuse poured forth upon

Whitman by his own countrymen; the tricklings of the British press

give but a moderate idea of it. The poet is known to repay scorn

with scorn. Emerson can, however, from the first be claimed as on

Whitman's side; nor, it is understood after some inquiry, has that

great thinker since then retreated from this position in

fundamentals, although his admiration may have entailed some worry

upon him, and reports of his recantation have been rife. Of other

writers on Whitman's side, expressing themselves with no measured

enthusiasm, one may cite Mr. M. D. Conway; Mr. W. D. O'Connor, who

wrote a pamphlet namedThe Good Grey

Poet; and Mr. John Burroughs, author ofWalt Whitman as Poet and Person,

published quite recently in New York. His thorough-paced admirers

declare Whitman to be beyond rivalrythepoet of the epoch; an estimate

which, startling as it will sound at the first, may nevertheless be

upheld, on the grounds that Whitman is beyond all his competitors a

man of the period, one of audacious personal ascendant, incapable

of all compromise, and an initiator in the scheme and form of his

works.Certain faults are charged against him, and, as far as they

are true, shall frankly stand confessed—some of them as very

serious faults. Firstly, he speaks on occasion of gross things in

gross, crude, and plain terms. Secondly, he uses some words absurd

or ill-constructed, others which produce a jarring effect in

poetry, or indeed in any lofty literature. Thirdly, he sins from

time to time by being obscure, fragmentary, and

agglomerative—giving long strings of successive and detached items,

not, however, devoid of a certain primitive effectiveness.

Fourthly, his self- assertion is boundless; yet not always to be

understood as strictly or merely personal to himself, but sometimes

as vicarious, the poet speaking on behalf of all men, and every man

and woman. These and any other faults appear most harshly on a

cursory reading; Whitman is a poet who bears and needs to be read

as a whole, and then the volume and torrent of his power carry the

disfigurements along with it, and away.The subject-matter of Whitman's poems, taken individually, is

absolutely miscellaneous: he touches upon any and every subject.

But he has prefixed to his last edition an "Inscription" in the

following terms, showing that the key-words of the whole book are

two—"One's-self" and "En Masse:"—Small is the theme of the following chant, yet the

greatest.—namely, ONE'S-SELF; that wondrous thing, a simple

separate person. That, for the use of the New World, I sing. Man's

physiology complete, from top to toe, I sing. Not physiognomy

alone, nor brain alone, is worthy for the Muse: I say the form

complete is worthier far. The female equally with the male I sing.

Nor cease at the theme of One's-self. I speak the word of the

modern, the word EN MASSE. My days I sing, and the lands—with

interstice I knew of hapless war. O friend, whoe'er you are, at

last arriving hither to commence, I feel through every leaf the

pressure of your hand, which I return. And thus upon our journey

linked together let us go.The book, then, taken as a whole, is the poem both of

Personality and of Democracy; and, it may be added, of American

nationalism. It ispar excellencethe modern poem. It is distinguished also by this

peculiarity— that in it the most literal view of things is

continually merging into the most rhapsodic or passionately

abstract. Picturesqueness it has, but mostly of a somewhat

patriarchal kind, not deriving from the "word-painting" of

thelittérateur; a certain echo

of the old Hebrew poetry may even be caught in it, extra-modern

though it is. Another most prominent and pervading quality of the

book is the exuberant physique of the author. The conceptions are

throughout those of a man in robust health, and might alter much

under different conditions.Further, there is a strong tone of paradox in Whitman's

writings. He is both a realist and an optimist in extreme measure:

he contemplates evil as in some sense not existing, or, if

existing, then as being of as much importance as anything else. Not

that he is a materialist; on the contrary, he is a most strenuous

assertor of the soul, and, with the soul, of the body as its

infallible associate and vehicle in the present frame of things.

Neither does he drift into fatalism or indifferentism; the energy

of his temperament, and ever-fresh sympathy with national and other

developments, being an effectual bar to this. The paradoxical

element of the poems is such that one may sometimes find them in

conflict with what has preceded, and would not be much surprised if

they said at any moment the reverse of whatever they do say. This

is mainly due to the multiplicity of the aspects of things, and to

the immense width of relation in which Whitman stands to all sorts

and all aspects of them.But the greatest of this poet's distinctions is his absolute

and entire originality. He may be termed formless by those who, not

without much reason to show for themselves, are wedded to the

established forms and ratified refinements of poetic art; but it

seems reasonable to enlarge the canon till it includes so great and

startling a genius, rather than to draw it close and exclude him.

His work is practically certain to stand as archetypal for many

future poetic efforts—so great is his power as an originator, so

fervid his initiative. It forms incomparably thelargestperformance of our period in

poetry. Victor Hugo'sLégende des

Sièclesalone might be named with it for

largeness, and even that with much less of a new starting-point in

conception and treatment. Whitman breaks with all precedent. To

what he himself perceives and knows he has a personal relation of

the intensest kind: to anything in the way of prescription, no

relation at all. But he is saved from isolation by the depth of his

Americanism; with the movement of his predominant nation he is

moved. His comprehension, energy, and tenderness are all extreme,

and all inspired by actualities. And, as for poetic genius, those

who, without being ready to concede that faculty to Whitman,

confess his iconoclastic boldness and his Titanic power of

temperament, working in the sphere of poetry, do in effect confess

his genius as well.Such, still further condensed, was the critical summary which

I gave of Whitman's position among poets. It remains to say

something a little more precise of the particular qualities of his

works. And first, not to slur over defects, I shall extract some

sentences from a letter which a friend, most highly entitled to

form and express an opinion on any poetic question—one, too, who

abundantly upholds the greatness of Whitman as a poet—has addressed

to me with regard to the criticism above condensed. His

observations, though severe on this individual point, appear to me

not other than correct. "I don't think that you quite put strength

enough into your blame on one side, while you make at least enough

of minor faults or eccentricities. To me it seems always that

Whitman's great flaw is a fault of debility, not an excess of

strength—I mean his bluster. His own personal and national

self-reliance and arrogance, I need not tell you, I applaud, and

sympathise and rejoice in; but the blatant ebullience of feeling

and speech, at times, is feeble for so great a poet of so great a

people. He is in part certainly the poet of democracy; but not

wholly,becausehe tries so

openly to be, and asserts so violently that he is— always as if he

was fighting the case out on a platform. This is the only thing I

really or greatly dislike or revolt from. On the whole" (adds my

correspondent), "my admiration and enjoyment of his greatness grow

keener and warmer every time I think of him"—a feeling, I may be

permitted to observe, which is fully shared by myself, and, I

suppose, by all who consent in any adequate measure to recognise

Whitman, and to yield themselves to his influence.To continue. Besides originality and daring, which have been

already insisted upon, width and intensity are leading

characteristics of his writings—width both of subject-matter and of

comprehension, intensity of self-absorption into what the poet

contemplates and expresses. He scans and presents an enormous

panorama, unrolled before him as from a mountain-top; and yet,

whatever most large or most minute or casual thing his eye glances

upon, that he enters into with a depth of affection which

identifies him with it for a time, be the object what it may. There

is a singular interchange also of actuality and of ideal substratum

and suggestion. While he sees men, with even abnormal exactness and

sympathy, as men, he sees them also "as trees walking," and admits

us to perceive that the whole show is in a measure spectral and

unsubstantial, and the mask of a larger and profounder reality

beneath it, of which it is giving perpetual intimations and

auguries. He is the poet indeed of literality, but of passionate

and significant literality, full of indirections as well as

directness, and of readings between the lines. If he is the 'cutest

of Yankees, he is also as truly an enthusiast as any the most

typical poet. All his faculties and performance glow into a white

heat of brotherliness; and there is apoignancyboth of tenderness and of

beauty about his finer works which discriminates them quite as much

as their modernness, audacity, or any other exceptional point. If

the reader wishes to see the great and more intimate powers of

Whitman in their fullest expression, he may consult theNocturn for the Death of Lincoln; than

which it would be difficult to find anywhere a purer, more

elevated, more poetic, more ideally abstract, or at the same time

more pathetically personal, threnody—uniting the thrilling chords

of grief, of beauty, of triumph, and of final unfathomed

satisfaction. With all his singularities, Whitman is a master of

words and of sounds: he has them at his command—made for, and

instinct with, his purpose—messengers of unsurpassable sympathy and

intelligence between himself and his readers. The entire book may

be called the paean of the natural man—not of the merely physical,

still less of the disjunctively intellectual or spiritual man, but

of him who, being a man first and foremost, is therein also a

spirit and an intellect.There is a singular and impressive intuition or revelation of

Swedenborg's: that the whole of heaven is in the form of one man,

and the separate societies of heaven in the forms of the several

parts of man. In a large sense, the general drift of Whitman's

writings, even down to the passages which read as most bluntly

physical, bear a striking correspondence or analogy to this dogma.

He takes man, and every organism and faculty of man, as the

unit—the datum—from which all that we know, discern, and speculate,

of abstract and supersensual, as well as of concrete and sensual,

has to be computed. He knows of nothing nobler than that unit man;

but, knowing that, he can use it for any multiple, and for any

dynamical extension or recast.Let us next obtain some idea of what this most remarkable

poet—the founder ofAmericanpoetry rightly to be so called, and the most sonorous poetic

voice of the tangibilities of actual and prospective democracy—is

in his proper life and person.Walt Whitman was born at the farm-village of West Hills, Long

Island, in the State of New York, and about thirty miles distant

from the capital, on the 31st of May 1819. His father's family,

English by origin, had already been settled in this locality for

five generations. His mother, named Louisa van Velsor, was of Dutch

extraction, and came from Cold Spring, Queen's County, about three

miles from West Hills. "A fine-looking old lady" she has been

termed in her advanced age. A large family ensued from the

marriage. The father was a farmer, and afterwards a carpenter and

builder; both parents adhered in religion to "the great Quaker

iconoclast, Elias Hicks." Walt was schooled at Brooklyn, a suburb

of New York, and began life at the age of thirteen, working as a

printer, later on as a country teacher, and then as a miscellaneous

press-writer in New York. From 1837 to 1848 he had, as Mr.

Burroughs too promiscuously expresses it, "sounded all experiences

of life, with all their passions, pleasures, and abandonments." In

1849 he began travelling, and became at New Orleans a newspaper

editor, and at Brooklyn, two years afterwards, a printer. He next

followed his father's business of carpenter and builder. In 1862,

after the breaking-out of the great Civil War, in which his

enthusiastic unionism and also his anti-slavery feelings attached

him inseparably though not rancorously to the good cause of the

North, he undertook the nursing of the sick and wounded in the

field, writing also a correspondence in theNew

York Times. I am informed that it was through

Emerson's intervention that he obtained the sanction of President

Lincoln for this purpose of charity, with authority to draw the

ordinary army rations; Whitman stipulating at the same time that he

would not receive any remuneration for his services. The first

immediate occasion of his going down to camp was on behalf of his

brother, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Whitman, of the 51st New York

Veterans, who had been struck in the face by a piece of shell at

Fredericksburg. From the spring of 1863 this nursing, both in the

field and more especially in hospital at Washington, became his

"one daily and nightly occupation;" and the strongest testimony is

borne to his measureless self-devotion and kindliness in the work,

and to the unbounded fascination, a kind of magnetic attraction and

ascendency, which he exercised over the patients, often with the

happiest sanitary results. Northerner or Southerner, the

belligerents received the same tending from him. It is said that by

the end of the war he had personally ministered to upwards of

100,000 sick and wounded. In a Washington hospital he caught, in

the summer of 1864, the first illness he had ever known, caused by

poison absorbed into the system in attending some of the worst

cases of gangrene. It disabled him for six months. He returned to

the hospitals towards the beginning of 1865, and obtained also a

clerkship in the Department of the Interior. It should be added

that, though he never actually joined the army as a combatant, he

made a point of putting down his name on the enrolment- lists for

the draft, to take his chance as it might happen for serving the

country in arms. The reward of his devotedness came at the end of

June 1865, in the form of dismissal from his clerkship by the

minister, Mr. Harlan, who learned that Whitman was the author of

theLeaves of Grass; a book

whose outspokenness, or (as the official chief considered it)

immorality, raised a holy horror in the ministerial breast. The

poet, however, soon obtained another modest but creditable post in

the office of the Attorney-General. He still visits the hospitals

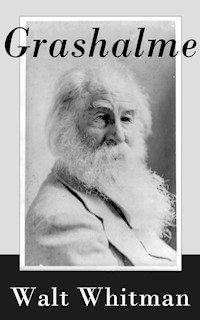

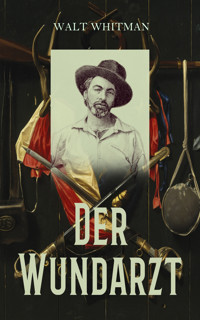

on Sundays, and often on other days as well.The portrait of Mr. Whitman reproduced in the present volume

is taken from an engraving after a daguerreotype given in the

originalLeaves of Grass. He is

much above the average size, and noticeably well-proportioned—a

model of physique and of health, and, by natural consequence, as

fully and finely related to all physical facts by his bodily

constitution as to all mental and spiritual facts by his mind and

his consciousness. He is now, however, old-looking for his years,

and might even (according to the statement of one of his

enthusiasts, Mr. O'Connor) have passed for being beyond the age for

the draft when the war was going on. The same gentleman, in

confutation of any inferences which might be drawn from theLeaves of Grassby a Harlan or other

Holy Willie, affirms that "one more irreproachable in his relations

to the other sex lives not upon this earth"—an assertion which one

must take as one finds it, having neither confirmatory nor

traversing evidence at hand. Whitman has light blue eyes, a florid

complexion, a fleecy beard now grey, and a quite peculiar sort of

magnetism about him in relation to those with whom he comes in

contact. His ordinary appearance is masculine and cheerful: he

never shows depression of spirits, and is sufficiently

undemonstrative, and even somewhat silent in company. He has always

been carried by predilection towards the society of the common

people; but is not the less for that open to refined and artistic

impressions—fond of operatic and other good music, and discerning

in works of art. As to either praise or blame of what he writes, he

is totally indifferent, not to say scornful—having in fact a very

decisive opinion of his own concerning its calibre and destinies.

Thoreau, a very congenial spirit, said of Whitman, "He is

Democracy;" and again, "After all, he suggests something a little

more than human." Lincoln broke out into the exclamation,

"Well,helooks like a man!"

Whitman responded to the instinctive appreciation of the President,

considering him (it is said by Mr. Burroughs) "by far the noblest

and purest of the political characters of the time;" and, if

anything can cast, in the eyes of posterity, an added halo of

brightness round the unsullied personal qualities and the great

doings of Lincoln, it will assuredly be the written monument reared

to him by Whitman.The best sketch that I know of Whitman as an accessible human

individual is that given by Mr. Conway.[4] I borrow from it the

following few details. "Having occasion to visit New York soon

after the appearance of Walt Whitman's book, I was urged by some

friends to search him out…. The day was excessively hot, the

thermometer at nearly 100°, and the sun blazed down as only on

sandy Long Island can the sun blaze…. I saw stretched upon his

back, and gazing up straight at the terrible sun, the man I was

seeking. With his grey clothing, his blue-grey shirt, his iron-grey

hair, his swart sunburnt face and bare neck, he lay upon the

brown-and-white grass—for the sun had burnt away its greenness—and

was so like the earth upon which he rested that he seemed almost

enough a part of it for one to pass by without recognition. I

approached him, gave my name and reason for searching him out, and

asked him if he did not find the sun rather hot. 'Not at all too

hot,' was his reply; and he confided to me that this was one of his

favourite places and attitudes for composing 'poems.' He then

walked with me to his home, and took me along its narrow ways to

his room. A small room of about fifteen feet square, with a single

window looking out on the barren solitudes of the island; a small

cot; a wash-stand with a little looking-glass hung over it from a

tack in the wall; a pine table with pen, ink, and paper on it; an

old line-engraving representing Bacchus, hung on the wall, and

opposite a similar one of Silenus: these constituted the visible

environments of Walt Whitman. There was not, apparently, a single

book in the room…. The books he seemed to know and love best were

the Bible, Homer, and Shakespeare: these he owned, and probably had

in his pockets while we were talking. He had two studies where he

read; one was the top of an omnibus, and the other a small mass of

sand, then entirely uninhabited, far out in the ocean, called Coney

Island…. The only distinguished contemporary he had ever met was

the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, of Brooklyn, who had visited him…. He

confessed to having no talent for industry, and that his forte was

'loafing and writing poems:' he was poor, but had discovered that

he could, on the whole, live magnificently on bread and water…. On

no occasion did he laugh, nor indeed did I ever see him

smile."[Footnote 4: In theFortnightly

Review, 15th October 1866.]The first trace of Whitman as a writer is in the pages of

theDemocratic Reviewin or

about 1841. Here he wrote some prose tales and sketches—poor stuff

mostly, so far as I have seen of them, yet not to be wholly

confounded with the commonplace. One of them is a tragic

school-incident, which may be surmised to have fallen under his

personal observation in his early experience as a teacher. His

first poem of any sort was namedBlood

Money, in denunciation of the Fugitive Slave

Law, which severed him from the Democratic party. His first

considerable work was theLeaves of

Grass. He began it in 1853, and it underwent two

or three complete rewritings prior to its publication at Brooklyn

in 1855, in a quarto volume—peculiar-looking, but with something

perceptibly artistic about it. The type of that edition was set up

entirely by himself. He was moved to undertake this formidable

poetic work (as indicated in a private letter of Whitman's, from

which Mr. Conway has given a sentence or two) by his sense of the

great materials which America could offer for a really American

poetry, and by his contempt for the current work of his

compatriots—"either the poetry of an elegantly weak sentimentalism,

at bottom nothing but maudlin puerilities or more or less musical

verbiage, arising out of a life of depression and enervation as

their result; or else that class of poetry, plays, &c., of

which the foundation is feudalism, with its ideas of lords and

ladies, its imported standard of gentility, and the manners of

European high-life-below-stairs in every line and verse." Thus

incited to poetic self-expression, Whitman (adds Mr. Conway) "wrote

on a sheet of paper, in large letters, these words, 'Make the

Work,' and fixed it above his table, where he could always see it

whilst writing. Thenceforth every cloud that flitted over him,

every distant sail, every face and form encountered, wrote a line

in his book."TheLeaves of Grassexcited no sort of notice until a letter from Emerson[5]

appeared, expressing a deep sense of its power and magnitude. He

termed it "the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that

America has yet contributed."[Footnote 5: Mr. Burroughs (to whom I have recourse for most

biographical facts concerning Whitman) is careful to note, in order

that no misapprehension may arise on the subject, that, up to the

time of his publishing theLeaves of

Grass, the author had not read either the essays

or the poems of Emerson.]The edition of about a thousand copies sold off in less than

a year. Towards the end of 1856 a second edition in 16mo appeared,

printed in New York, also of about a thousand copies. Its chief

feature was an additional poem beginning "A Woman waits for me." It

excited a considerable storm. Another edition, of about four to

five thousand copies, duodecimo, came out at Boston in 1860-61,

including a number of new pieces. TheDrum

Taps, consequent upon the war, with theirSequel, which comprises the poem on

Lincoln, followed in 1865; and in 1867, as I have already noted, a

complete edition of all the poems, including a supplement

namedSongs before Parting. The

first of all theLeaves of Grass, in point of date, was the long and powerful composition

entitledWalt Whitman—perhaps

the most typical and memorable of all of his productions, but shut

out from the present selection for reasons given further on. The

final edition shows numerous and considerable variations from all

its precursors; evidencing once again that Whitman is by no means

the rough-and-ready writer, panoplied in rude art and egotistic

self-sufficiency, that many people suppose him to be. Even since

this issue, the book has been slightly revised by its author's own

hand, with a special view to possible English circulation. The copy

so revised has reached me (through the liberal and friendly hands

of Mr. Conway) after my selection had already been decided on; and

the few departures from the last printed text which might on

comparison be found in the present volume are due to my having had

the advantage of following this revised copy. In all other respects

I have felt bound to reproduce the last edition, without so much as

considering whether here and there I might personally prefer the

readings of the earlier issues.The selection here offered to the English reader contains a

little less than half the entire bulk of Whitman's poetry. My

choice has proceeded upon two simple rules: first, to omit entirely

every poem which could with any tolerable fairness be deemed

offensive to the feelings of morals or propriety in this peculiarly

nervous age; and, second, to include every remaining poem which

appeared to me of conspicuous beauty or interest. I have also

inserted the very remarkable prose preface which Whitman printed in

the original edition ofLeaves of

Grass, an edition that has become a literary

rarity. This preface has not been reproduced in any later

publication, although its materials have to some extent been worked

up into poems of a subsequent date.[6] From this prose composition,

contrary to what has been my rule with any of the poems, it has

appeared to me permissible to omit two or three short phrases which

would have shocked ordinary readers, and the retention of which,

had I held it obligatory, would have entailed the exclusion of the

preface itself as a whole.[Footnote 6: Compare, for instance, the Preface, pp. 38, 39,

with the poemTo a Foiled Revolter or

Revoltress, p. 133.]A few words must be added as to the indecencies scattered

through Whitman's writings. Indecencies or improprieties—or, still

better, deforming crudities—they may rightly be termed; to call

them immoralities would be going too far. Whitman finds himself,

and other men and women, to be a compound of soul and body; he

finds that body plays an extremely prominent and determining part

in whatever he and other mundane dwellers have cognisance of; he

perceives this to be the necessary condition of things, and

therefore, as he fully and openly accepts it, the right condition;

and he knows of no reason why what is universally seen and known,

necessary and right, should not also be allowed and proclaimed in

speech. That such a view of the matter is entitled to a great deal

of weight, and at any rate to candid consideration and

construction, appears to me not to admit of a doubt: neither is it

dubious that the contrary view, the only view which a mealy-mouthed

British nineteenth century admits as endurable, amounts to the

condemnation of nearly every great or eminent literary work of past

time, whatever the century it belongs to, the country it comes

from, the department of writing it illustrates, or the degree or

sort of merit it possesses. Tenth, second, or first century before

Christ—first, eighth, fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth,

seventeenth, or even eighteenth century A.D.—it is still the same:

no book whose subject-matter admits as possible of an impropriety

according to current notions can be depended upon to fail of

containing such impropriety,—can, if those notions are accepted as

the canon, be placed with a sense of security in the hands of girls

and youths, or read aloud to women; and this holds good just as

much of severely moral or plainly descriptive as of avowedly

playful, knowing, or licentious books. For my part, I am far from

thinking that earlier state of literature, and the public feeling

from which it sprang, the wrong ones— and our present condition the

only right one. Equally far, therefore, am I from indignantly

condemning Whitman for every startling allusion or expression which

he has admitted into his book, and which I, from motives of policy,

have excluded from this selection; except, indeed, that I think

many of his tabooed passages are extremely raw and ugly on the

ground of poetic or literary art, whatever aspect they may bear in

morals. I have been rigid in exclusion, because it appears to me

highly desirable that a fair verdict on Whitman should now be

pronounced in England on poetic grounds alone; and because it was

clearly impossible that the book, with its audacities of topic and

of expression included, should run the same chance of justice, and

of circulation through refined minds and hands, which may possibly

be accorded to it after the rejection of all such peccant poems. As

already intimated, I have not in a single instance excised

anypartsof poems: to do so

would have been, I conceive, no less wrongful towards the

illustrious American than repugnant, and indeed unendurable, to

myself, who aspire to no Bowdlerian honours. The consequence is,

that the reader losesin totoseveral important poems, and some extremely fine ones—notably

the one previously alluded to, of quite exceptional value and

excellence, entitledWalt Whitman. I sacrifice them grudgingly; and yet willingly, because I

believe this to be the only thing to do with due regard to the one

reasonable object which a selection can subserve—that of paving the

way towards the issue and unprejudiced reception of a complete

edition of the poems in England. For the benefit of

misconstructionists, let me add in distinct terms that, in respect

of morals and propriety, I neither admire nor approve the

incriminated passages in Whitman's poems, but, on the contrary,

consider that most of them would be much better away; and, in

respect of art, I doubt whether even one of them deserves to be

retained in the exact phraseology it at present exhibits. This,

however, does not amount to saying that Whitman is a vile man, or a

corrupt or corrupting writer; he is none of these.The only division of his poems into sections, made by Whitman

himself, has been noted above:Leaves of

Grass,Songs before

Parting, supplementary to the preceding,

andDrum Taps, with

theirSequel. The peculiar

title,Leaves of Grass, has

become almost inseparable from the name of Whitman; it seems to

express with some aptness the simplicity, universality, and

spontaneity of the poems to which it is applied.Songs before Partingmay indicate that

these compositions close Whitman's poetic roll.Drum Tapsare, of course, songs of the

Civil War, and theirSequelis

mainly on the same theme: the chief poem in this last section being

the one on the death of Lincoln. These titles all apply to fully

arranged series of compositions. The present volume is not in the

same sense a fully arranged series, but a selection: and the

relation of the poemsinter seappears to me to depend on altered conditions, which, however

narrowed they are, it may be as well frankly to recognise in

practice. I have therefore redistributed the poems (a latitude of

action which I trust the author may not object to), bringing

together those whose subject-matter seems to warrant it, however

far separated they may possibly be in the original volume. At the

same time, I have retained some characteristic terms used by

Whitman himself, and have named my sections

respectively—1. Chants Democratic (poems of democracy). 2. Drum Taps (war

songs). 3. Walt Whitman (personal poems). 4. Leaves of Grass

(unclassified poems). 5. Songs of Parting (missives).The first three designations explain themselves. The

fourth,Leaves of Grass, is not

so specially applicable to the particular poems of that section

here as I should have liked it to be; but I could not consent to

drop this typical name. TheSongs of

Parting, my fifth section, are compositions in

which the poet expresses his own sentiment regarding his works, in

which he forecasts their future, or consigns them to the reader's

consideration. It deserves mention that, in the copy of Whitman's

last American edition revised by his own hand, as previously

noticed, the series termedSongs of

Partinghas been recast, and made to consist of

poems of the same character as those included in my section No.

5.