Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

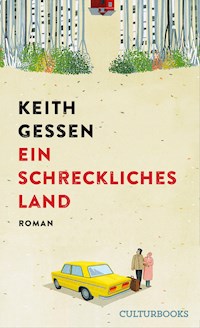

'Given the bedlam it describes, Raising Raffi is impressively clear-sighted, entertaining and analytical' - Financial Times 'A wise, mild and enviably lucid book about a chaotic scene' - Dwight Garner, New York Times 'Engaging, accessible, down to earth... There is much wry humour here' - James Cook, Times Literary Supplement Keith Gessen had always assumed that he would have kids, but couldn't imagine what parenthood would be like, nor what kind of parent he would be. Then, one Tuesday night in early June, Raffi was born, a child as real and complex and demanding of his parents' energy as he was singularly magical. Fatherhood is another country: a place where the old concerns are swept away, where the ordering of time is reconstituted, where days unfold according to a child's needs. Like all parents, Gessen wants to do what is best for his child. But he has no idea what that is. Written over the first five years of Raffi's life, Raising Raffi examines the profound, overwhelming, often maddening experience of being a dad. How do you instil in your child a sense of his heritage without passing on that history's darker sides? Is parental anger normal, possibly useful, or is it inevitably destructive? And what do you do, in a pandemic, when the whole world seems to fall apart? By turns hilarious and poignant, Raising Raffi is a story of what it means to invent the world anew.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 330

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

Raising Raffi

A Book about Fatherhood

(For People Who Would Never Read Such a Book)

Keith Gessen

v

For Emily

vi

Contents

Raising Raffi

x

Author’s Note

I wrote this book out of desperation.

For the first few months of my son Raffi’s life, I felt like I was merely surviving. Through the sleeplessness and terror, I put one parenting foot in front of the other and tried not to look too far ahead. But when this passed, what I wanted, more than anything, was to talk. I had never before experienced such a contradictory mass of feelings; had never engaged in an activity so simultaneously mundane and significant; had never met anyone like screaming two-month-old Raffi, or cuddly one-year-old Raffi (“Uck,” he would say, when he wanted a hug), or scourge of our household two-and‑a‑half-year-old Raffi. Through each of these phases I was amazed by his transformations, his progress, and my own complicated reactions. I wanted to know if other people were going through the same.

Parents talked, of course. My wife, the writer Emily Gould, and I talked all the time about Raffi, and we sought out other parents on the playgrounds, on street corners, even on the subway. Some of us, when we talked, couldn’t help but brag. “He 2started sleeping through the night last week,” someone might say, alienating their interlocutor forever. Or: “His grandparents took him for the weekend, and we slept late.” (An active in‑town grandparent was worth, by my informal calculations, about forty thousand dollars a year.) Others went in the other direction. Their child wouldn’t nap; he threw his food onto the floor; he bit a kid in day care. Emily and I were in the self-deprecating camp. But of course this left out something, too—the physical joy of being with Raffi, the hilarity of much of what he did. There was, in short, a limit to what you could get at when chatting with other parents. I felt like these conversations never went far enough.

There were books about parenting. Some of them were very good; most were not. In its main current, parenting literature was the literature of advice. The books diagnosed a sickness—your child’s sleep “problem,” your son’s behavior “issue”—and promised to solve it. When the solution didn’t work, you blamed yourself. Then you sought out another book, one that would “work” better, and went through the cycle again.

There was a particular gap, I thought, in the dad literature. In the few books out there, we were either stupid dad, who can’t do anything right, or superdad, a self-proclaimed feminist and caretaker. I was sure those dads existed, but I didn’t know any. The dads I knew took their parenting responsibilities seriously, were not idiots, and did their best around the house and with the kids. With some notable exceptions, they did less parenting than their spouses. (The gay dads I knew hired a lot of child 3care.) Nonetheless, they thought it was one of the most important things they were going to do with their lives.

At the time I started working on this book, when Raffi had just turned three, I was supposed to be doing other things. I had a novel coming out that I needed to promote, and then a nonfiction book on U.S.– Russia relations that I should have been researching. But I couldn’t stop thinking about Raffi: about our situation with him; about the situation of all parents with their little kids. I began taking notes and eventually I started writing these essays.

I felt ridiculous about it at times. To write about parenting when you are a father is like writing about literature when you can hardly read. Almost without exception, in every male-female relationship I encountered, the mothers knew more about their kids than the fathers and parented them better. My own relationship was no exception. Emily was an extremely well-informed parent who also, not long after Raffi was born, started writing occasional essays about him. I love those essays as much as anything she has written. But there were things that I did with Raffi—talk Russian, play sports, yell in Russian—that were particular to my experience. And I came to think there was some value in recording my own groping toward knowledge in this most important of human endeavors, a kind of record of a primitive consciousness making its way toward the light. I was part of the first generation of men who, for various reasons, were spending more time with their kids than previous generations. That seemed notable to me.4

I recently asked my own father if he remembered my second-grade teacher, Ms. Lynch, because I had just called her up to interview her about education. He said he didn’t, and wouldn’t. “But you must have gone to the parent-teacher conferences?” I said. “Oh no,” said my dad. “I was at work.” My father had relocated us halfway around the world so that we wouldn’t have to grow up in the Soviet Union; drove me to every single hockey game I ever played in from the ages of six to sixteen, which was hundreds of hockey games; almost never traveled for work; and taught me math, physics, how to drive, and how to throw a left hook. He was hardly an absent father. But to him the idea of attending a parent-teacher conference was risible, whereas I consider the quarterly parent-teacher conferences for Raffi major events in my life.

This book consists of nine essays, arranged by subject: birth, zero to two, bilingualism, discipline, picture books, schools, the pandemic, sports, and cross-cultural parenting. Each of the essays describes my experience as a parent; draws on some of the literature and conversations I’ve found most helpful (or unhelpful) in thinking through this experience; and comes or doesn’t come to a conclusion. I’ve tried to make it so that the essays can be read independently, if a busy parent doesn’t have any interest in, for example, bilingualism; but I’ve also sought to avoid repetition and placed things in a more or less chronological way so that a reader going through the entire book can see Raffi (and me and his mother) slowly moving into the future.

Most of the material is from my personal experience, though 5as you’ll see, one of the things I do to understand my experience is read. Where appropriate, I have also used my training as a journalist to talk with some of the people I thought would have the most to say on a given subject, whether it’s the purpose of education, the nature of Russian parenting, or the lessons of parenting research in comparative perspective. I hope these conversations do not seem out of place; they were important to me in thinking through these issues.

I wrote some of these essays earlier than others, and in instances where I have changed my mind or learned a lot more about the subject—for example, by having another child and seeing him, at age three, suddenly turn from angel to avenger—I have tried to incorporate that later insight into the text. The thing I’ve learned about parenting, the thing that the parenting books don’t tell you, is that time is the only solution. You do eventually figure it out, or start to. But by then it is often too late. The damage—to your child, yourself, your marriage—has already been done. That is the way of knowledge, though. In its purest form, it always comes too late.6

Home Birth

I was not prepared to be a father—this much I knew. I didn’t have a job and I lived in one of the most expensive cities on the planet. I had always assumed that I’d have kids, but I had spent zero minutes thinking about them. In short, though not young, I was stupid.

Emily told me she was pregnant when we were walking down Thirty-Fourth Street in Manhattan, on the way to Macy’s to shop for wedding rings. Our wedding was a few weeks away, and I had, as usual, put off preparing until the last minute. I had a fellowship at the time at the New York Public Library in midtown, and I must have googled “wedding rings near me.” Macy’s it was. All around us on Thirty-Fourth Street people were shopping and hurrying and driving and honking. Emily told me, and I thought, “OK. Here we go. We are going to have a kid.”

Then I thought: We need to get some very cheap wedding rings at Macy’s.

I was born in Moscow and came to the United States with my parents and older sibling when I was six. I grew up in a suburb 8outside of Boston and found it boring and dreamed of leaving to become a writer. After college, I moved to New York and worked odd jobs and wrote short stories, which I sent to literary magazines, which never wrote me back. To see my name in print, I started doing journalism. I found I really liked it. I also started translating things—stories, an oral history, poems—from Russian. Traveling to Russia and seeing its version of capitalism up close converted me to democratic socialism. Eventually I started a left-wing literary magazine, n+1, with some friends, published a novel, and traveled as much as possible to Russia to write about it. This was a decent literary career, truly more than I ever could have hoped for, but it did not bring in a lot of income; when Emily and I met I was living with two roommates in a grand but ancient and cockroach-infested apartment on Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn.

At the time, Emily was a writer for Gawker, a media gossip website. She was brilliant, beautiful, and very funny; she could also be very mean. She had grown up in an upper-middle-class household in suburban Maryland, but she had a chip on her shoulder. She was also a very good cook. We dated for a while, broke up (she dumped me at a Starbucks in Cobble Hill that later closed during the pandemic), and then started dating again. Eventually we moved in together, to an apartment above a bar in Bedford-Stuyvesant. By this point Emily had quit working for Gawker and published a well-received book of essays. With her best friend, Ruth, she started a small feminist publishing house, Emily Books; she worked for a while at a publishing 9start-up, then got sick of it. The year she got pregnant, she published her first novel, Friendship, about two best friends whose relationship is disrupted when one of them gets … pregnant. I was working on my second novel, about Russia, and had received a yearlong fellowship at the New York Public Library to research and write it. The fellowship was the bulk of our income that year. Strictly speaking, we still didn’t have much money, but that was OK, because we also didn’t have any kids.

Now, at Macy’s, we couldn’t get the attention of the saleswoman in the giant ring section. I would have hung around until she got to us, but Emily looked disappointed—the mother of my child! I couldn’t make her wait. We got on the subway to Brooklyn and bought rings above our budget at a cute little store in Williamsburg.

I suppose it isn’t exactly true that I hadn’t thought about kids. I hadn’t thought about actual birth, or what sort of clothes a baby wears, or about the practicalities of early infancy. “As a child, from the moment I gained some understanding of what it entailed, I worried about childbirth,” writes Rachel Cusk in A Life’s Work, her dark, brilliant memoir of motherhood. She feared its pain and its violence and what would happen on the other side. To this, truly, I had given zero thought.

But I see in retrospect that I had spent years steeling myself for the eventuality of a “family.” I had imbibed the heroic male literature of family neglect: Henry James, who skipped a family funeral because he was finishing a story (“One has no business to have any children,” one of his characters famously says. “I 10mean of course if one wants to do anything good”); Philip Roth, who refused to have children; Tolstoy, who had many children and a long marriage but who still managed, at the very end of his life, to walk out on them. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote beautiful letters on life and literature to his daughter, Frances, but only after Zelda had been committed to a mental institution and Fitzgerald himself was floundering in Hollywood. “The intellect of man must choose,” William Butler Yeats had written: “Perfection of the life, or of the work.” I would choose the work, I told myself over and over. I had been married once before, while still in college, and at the time I was adamant that the relationship must not interfere with my writing. My time must be my own; I must have adequate amounts of it; if my writing does not get done, then all is lost. My insistence on this eventually doomed the relationship. We broke up. The lesson I took from this was not that I should keep things in perspective, but that I should arrange my life so it revolved wholly around literature. In the pages of n+1 I pledged never to teach writing, or to write for money, or to do anything else to distract from what I thought of as the highest calling one could have.

One time, not long after Emily and I had started dating, I hosted the Russian writer Ludmilla Petrushevskaya in New York. With Anya, my ex‑wife, I had translated a book of her scary fairy tales, and Petrushevskaya, by then in her seventies, flew over to do some readings, shop for clothes for her kids at Century 21, and eat Thai food. She was, and is, in my opinion, the greatest living Russian writer, the final chronicler of that 11country’s life at the end of its most terrible century. One evening toward the end of her stay, while we were eating Thai food, she suddenly looked at me and said, apropos of nothing, “You know, Kostya, I started writing when I was a little girl. But I didn’t become a real writer until I had my first child.” I don’t know why she decided to say this to me. Maybe she was just talking. But at the time I thought it was because she saw in me a person leading a superfluous existence, a too-easy life. I had thought I’d made my life pure so I could devote it to literature. That’s not what Petrushevskaya saw.

Now here I was, five years later. I was going to be a father. I was elated, and I was scared. This was serious business, involving doctors, nurses, life and death. Immediately I was worried about the baby. Was he comfortable? Was he safe? Was he getting the proper nutrients? At the same time, I started trying to figure out, almost despite myself, how I was going to make sure the baby didn’t interfere with my work. I had a vague foreboding that he would, though I couldn’t quite figure out why. What exactly was so time-consuming about parenthood? Why couldn’t people sleep? And work? When a baby was little, couldn’t you rock his cradle as you answered emails or wrote a novel? When a baby was crying at night, couldn’t you put in earplugs? I was worried about the baby, but worried, too, about myself.

I had one friend from graduate school, Eric, with whom I’d kept in touch after the birth of his child. I asked him out for a beer and told him that Emily was pregnant. I asked, “What do I need to know?”12

“It’s tough,” Eric said. “It’s not easy. You need a lot of stuff.”

Stuff?

“Yeah, a lot of stuff.”

Stuff. Of course! What we needed was stuff! I was delighted. Stuff was something I could handle. Emily and I started getting stuff. I bought a kid’s dresser—with a little nook up top for a changing pad—from some Russians in Sheepshead Bay. Emily’s friend Jess gave us her daughter’s old crib. Emily’s friend Lori gave us a bassinet. Eric, who planned to have another kid, loaned us a second bassinet. Emily’s parents bought us a car seat and a stroller. My father bought us the mattress for the crib. My friend A. J., who’d just had a baby, mailed us what looked like a large pillow with a little depression in it, which she called a “dog bed,” for putting our future baby down onto. We bought some onesies and some diapers and a changing pad. One day Eric’s wife, Rachael, a clothing designer, came by our place with a baby carrier. Her daughter was asleep in the car downstairs. Technically, I think, this was illegal. Rachael threw the carrier onto our bed. “Here,” she said. Someone had sent a stuffed bunny for the future baby and Rachael grabbed him by the throat and put him in the carrier. She secured one strap around her waist, then bent down over the bunny and threaded her arms through the shoulder straps. “Like that,” she said. We nodded, uncomprehending. “OK, bye,” said Rachael, and ran back down the stairs to her daughter. We were in awe. We now had a baby carrier.

The stuff was great. It kept the fear at bay. If the baby showed 13up tomorrow, we’d have a place to lay him down while he slept; a surface on which to change his diapers; methods to transport him by street or car. But still we were scared.

Or maybe I should stop saying “we.”

Before the baby, Emily and I were pretty similar. We both liked to drink coffee and read books and work on our laptops, sometimes together, at the café on the corner; we liked drinking a medium amount of alcohol with dinner; before going to bed we liked to watch an HBO show and eat a chocolate bar. If we were on the beach, we liked to go swimming. Emily was on her high school’s swim team and remained an excellent swimmer. We liked going to the movies.

Emily becoming pregnant both brought us closer and pushed us apart. For a while, including at our wedding, we were the only ones who knew. Then, later on, we were the ones to whom every little thing mattered: at the ultrasounds, we studied the expression on the face of the lab tech; we worried about the blood tests coming back; we examined the little sonogram photos to see if we could make out the features and character of our future baby.

But there was also no denying that this was all happening to Emily, inside of Emily, and not inside of me. It was as if we’d discovered that Emily had a superpower. I worshipped her.

We were scared of different things, then, and in different ways. I was scared of my ignorance. Emily was scared of physical pain. But Emily was also prepared. She had read the literature and she knew lots of moms. Once she became pregnant, 14she downloaded an app to her phone that told her all about the baby. “Our baby is the size of a pea,” she would tell me. Then: “Our baby is the size of a plum.” Eventually our baby was the size of an eggplant. He was in good hands with Emily. The weak link was me.

Time, at least, was on my side. Later on, time would turn on me. As I stood there swinging or rocking our baby so he would fall asleep; or walking him around the neighborhood in his stroller so he would fall asleep; or just kind of hanging out with him aimlessly, waiting for him to fall asleep, time moved too slowly. But during the pregnancy, time was my friend. Nine months was almost enough time for even me to get my act together. Through the sheer accumulation of days, I sometimes hoped, wisdom would come upon me.

Emily wanted a home birth. I thought this was crazy. Modern medicine had come so far! But she said she didn’t want to take a cab to the hospital and possibly give birth in it. This made sense. I imagined looking up at the taxi meter as my child was born and seeing, like, $198. I agreed to explore the option of home birth.

On Netflix we watched an unconvincing documentary called The Business of Being Born, in which former daytime talk show host Ricki Lake, pregnant with her second child, sings the praises of home birth and denounces the American hospital system, which pumps women full of drugs and then forces them to have 15C‑sections they don’t need. Toward the end of the film, Lake gives beautiful birth at home, no drugs needed. The director of the film is also pregnant, but ends up giving birth at the hospital because her baby is coming out the wrong way (legs or butt first, known as “breech,” as in breeches). The film is pretty compelling as an indictment of a savage and profit-seeking medical establishment. But in proposing home birth as a sort of opt-out movement, it is much less so. There are a lot of people who cannot or should not give birth at home. When the director has to “transfer” to the hospital to get an emergency C‑section, the news ought to be that her baby has survived. But in the context of the home-birthing paradigm, the director is made to seem like a failure.

Still, that didn’t mean we couldn’t have a home birth. We interviewed a midwife named B. She was young and seemed nice enough, but as we were wrapping up, she said a very strange thing. “I have a question for you,” she said. “If something goes wrong, will you still remain advocates of home birth?”

It took us a moment to process the question. If something goes wrong? With our baby? Will we be what? Of what? “Sure,” we managed, but what we were thinking was: Why would anything go wrong? And why would someone in her right mind ask that of two terrified people who had never given birth before? It felt like the midwife had an ideological commitment to home birth that went beyond her commitment to our unborn baby. It did not feel right.

I was not unwilling to discuss the possibility of something 16going wrong. In fact, I very much wanted to know what would happen if something went wrong: what our backup plan was; what hospital we’d go to and what doctor we would see. But I had no interest in discussing my advocacy or nonadvocacy of home birth in that scenario.

We continued to do research and talk to people. One friend warned me that his daughter’s shoulders had gotten stuck on her way out of the womb and that the doctor had reached in, deliberately broken her collarbone, and got her out. “Can’t do that at home,” he said. (Actually, this is not true—shoulder dystocia, as I later learned this was called, can be handled at home in the same way.) Another friend, whose husband was a doctor, said she couldn’t believe people gave birth at home in bathtubs. “The baby can’t breathe underwater!” she said. This also was incorrect—the baby has been breathing through the umbilical cord for months, and anyway, you were supposed to pull him out of the water immediately. But these bits of advice stuck with me and scared me. I was becoming increasingly concerned about home birth. Then we met Karen and Martine.

Karen and Martine were midwives in their fifties who ran a joint practice and had been doing this for years. Practically the first thing out of their mouths was a list of all that could go wrong with a home birth, every eventuality that would trigger the dreaded transfer to the hospital. A breech baby, like in the Ricki Lake film, to be sure, as there’s no way to turn him right side up again at home. Or a baby whose heart rate isn’t strong enough, indicating that he might be tangled in the umbilical 17cord. A baby turned the wrong way laterally rather than vertically, i.e., with his back to the mother’s back, is tricky but not impossible to deliver at home. (You can, at least theoretically, turn the baby around through the mother’s stomach with a towel.) There were several other scenarios along these lines. Karen and Martine described these before—in fact, instead of—describing how natural and wonderful a home birth was. They weren’t trying to sell us on home birth. They seemed instead to be saying that if our commitment to home birth was stronger than our commitment to the health of our unborn baby, or of his mother, then they did not want to work with us.

I was so relieved and grateful. I thought it would be a great honor to have our baby delivered by Karen or Martine. Emily agreed. We decided to have the birth at home.

Karen and Martine recommended a birth class specifically devoted to home births. This, too, was a hit. Our teacher was a lovely artist named Ellen. Every Tuesday for seven weeks we would sit on cushions in her living room alongside six other couples and discuss the birth process for two hours. We learned about the events leading up to labor: Braxton-Hicks contractions, which seem like contractions but aren’t; pre-labor, when the contractions start becoming more regular; and the commencement of official labor with the rupturing of the amniotic sac (the water breaking). We learned that labor itself had three stages: early labor, active labor, and then the “transition” phase. Early labor was relatively mild; active labor was painful and prolonged, and that was when you called the midwife; once the 18midwife arrived, the mother started pushing to get the baby out—transitioning him from the womb to the world.

It was a great class. I had absorbed from popular culture that birth classes taught women some kind of elaborate breathing technique for their contractions, but this had gone out of style. Rather than breathing in some specific way during active labor, Ellen advised women to do what comes naturally when you are in pain: to scream.

I was becoming more prepared, but I still wasn’t prepared. We bought and borrowed and accepted stuff; hired our midwives; wrote a letter to our insurance carrier asking them to pay for a home birth; took the class. We even came up with a sort of name for the baby, so we wouldn’t always have to call him “the baby.” It was a Russian name, in honor of my Russian heritage, but also the most implausible (to us) Russian name that we could think of—Yuri. It was implausible because, as Emily pointed out, mean kids would just call our baby Urine.

Still, it all seemed pretty unreal. Summer came. The library fellowship I was on ended. I returned all my books and cleared out my office. I was playing a lot of beer league hockey. Emily was writing an essay. We went about our lives.

Two weeks from the due date, with our baby now the size of a small watermelon, we had an appointment with Karen. For the first seven months of the pregnancy, we (or most often, just 19Emily) had to travel to various offices, whether Karen’s or Martine’s, or to the labs or medical offices where they had technology that Karen and Martine did not: Emily got ultrasounds in midtown and a blood test in Bay Ridge. Everything was fine. Our baby was a boy and had no genetic deformities. In the last two months, and this was a true luxury of home birth, the midwives came to our apartment. One reason was that it gave them a sense of our place for the day of the birth. But it was also a courtesy to the mother, to Emily, who by this point found it unpleasant to travel.

On this day, Karen went through her usual routine. She asked Emily how she was feeling, asked after her diet, and measured her stomach. All was in order. Then she took out a little heart rate kit, spread some oil on Emily’s stomach, and listened for the baby’s heartbeat.

We all heard it: thump-thump-thump-thump-silence. The fifth beat was missing. Thump-thump-thump-thump-silence. We looked at Karen, hoping she would say it was nothing, but she seemed concerned. Thump-thump-thump-thump-silence. She turned off the machine and turned it back on again. Thump-thump-thump-thump-silence.

“You need to go see a pediatric cardiologist,” she said.

I imagined making an appointment, waiting for the baby to be born, then figuring out a way to transport him to the doctor.

“Now,” said Karen. “Today.”

While we sat there in shock, Karen got on the phone and 20called a practice she knew in Union Square. She asked if they took our insurance. They did. Karen said we’d be coming right in.

I looked it up on Google Maps, which said that a cab and the subway would both take half an hour. But in my experience Google consistently underestimates traffic wait times. I imagined us sitting in traffic on Fourteenth Street with our little baby and his missing heartbeat. “I think we should take the train,” I said. Emily shrugged. She didn’t care. Karen drove us the three blocks to the subway and told us to call her after the appointment. She let us out, and then we were on our own.

It took a while for the G train to come. The platform, like most New York City subway platforms during the summer, was filthy. There was trash on the tracks, with rats scurrying this way and that, arranging their housekeeping. Some kind of water leaked slowly from a pipe near the ceiling. Emily looked really pregnant now, and I felt useless and lost. The baby, visible in Emily’s stomach, was nonetheless for me a total abstraction. Almost nothing in my life had actually changed. I had bought the dresser, put together the crib, attended the birth classes, and then basically checked out. Was I being punished in some way? Was there something I should have noticed, something that I’d missed, because I wasn’t paying enough attention?

To lighten the mood, I started saying something about Yuri.

“THAT’S NOT HIS NAME!” Emily said.

I stopped whatever it was that I was saying.

And Yuri was, indeed, not to be his name.21

Forty minutes later, at the cardiologist’s office, a poker-faced young woman took a number of photos of our baby’s little heart. Then the cardiologist came in and told us not to worry. There were two kinds of prenatal heart conditions that this could have been, and our baby had the benign version. Lots of stuff goes haywire in the brief period when the baby is preparing to leave the womb and enter the world, said the cardiologist. The entire respiratory apparatus has to reorganize itself to take in oxygen from the air instead of the umbilical cord. Sometimes there are hitches. Most of the time, they get worked out in the process of birth. He said to come see him once the baby was born, but for the moment he thought we were OK.

Six days later, I came home from a hockey game at midnight. Emily was up, watching a show in what was still the TV room, though the children’s dresser and crib were already hinting that its time was running out. “My contractions have started,” she said. But her water hadn’t broken. These could be Braxton-Hicks contractions or the actual contractions of pre-labor. Emily thought they were the real thing. Luckily, Martine was coming the next morning for the final pre-birth checkup. We went to sleep.

In the morning, Martine was happy to hear about the contractions. She checked the baby’s heartbeat. Thump-thump-thump-thump-silence. As Martine was doing the rest of the checkup, a large black spot appeared on Emily’s sweatpants.22

“Uh,” she said.

“Ah,” said Martine.

It was her water breaking: official labor had commenced! Martine, as always, was very calm. “Call me when the contractions are stronger and more frequent,” she said—and left! She had other stuff to do. We were a little bit surprised. It was eleven a.m.

For the next four hours, we hung out, watched a bunch of TV, and waited. “The one thing you must not do,” my friend George had told me, “is buy a bag of Milano cookies and eat them all while Emily is giving birth.” Apparently George, waiting in the hospital before the most active phase of his wife’s labor started, had become a little peckish and gone out to a deli and bought some Milanos. Then while she gave birth, he sort of stood there and mindlessly ate them all. They really are very delicious. Four years later she still had not forgiven him.

I managed not to eat a bunch of cookies, but I did make a mistake; we were watching a TV show that I thought was very funny, and I was delightedly laughing at it and so was Emily. But I failed to notice the moment she stopped laughing. She had been sitting next to me on a yoga blanket, occasionally getting on all fours during a contraction, but now her contractions had increased in magnitude. “What are you doing?!” Emily said as I laughed at our show. She was on all fours again, but grimacing. I turned off the TV.

I was the timekeeper and in a way the gatekeeper for the eventual call to Martine, and I was convinced that I would fuck 23it up by calling her too early. She would show up, say I was exaggerating the severity of the contractions, and leave. Then, after she left, Emily would give birth. It would be a catastrophe. But the contractions were very clear. They started getting closer and closer together and lasting longer too. The formula was 5‑1‑1: the contractions were to be less than five minutes apart, and last for longer than one minute, for one hour. I couldn’t really understand how a contraction could last longer than a minute, but then I saw Emily visibly in pain, moaning, groaning, wincing, for an entire minute, and was convinced. At four p.m., I called the doula Emily had hired and told her she should come. Then I read to her from the piece of paper on which I was recording the contraction statistics. “Should I call the midwife?” I asked.

“Yes!” she said. I called Martine.

She and her assistant came two hours later. By then the contractions were even stronger and more frequent. Emily threw up. She was in unbelievable pain, and the hard part was still to come. She started pushing at around seven. She pushed in our living room, then on the floor of our bedroom, and finally on our bed. Throughout the period of active labor, Martine’s assistant kept checking the baby’s heartbeat. Thump-thump-thump-thump-silence. Thump-thump-thump-thump-silence. But Emily kept pushing, and screaming, and pushing. There was a lot of blood. Some people say that gravity is your friend when you are getting the baby out, but there’s also something to be said for lying down and being maximally comfortable. Gravity, 24on its own, is not strong enough to get that baby out of you. At one point, when Emily was on the bed, just before the baby’s head started coming out, a geyser of blood shot out from her vagina. On the advice of our midwives, we had placed a plastic shower curtain under our bedding, so that blood wouldn’t get on the mattress, but the bloody geyser was not something we’d anticipated. It was high enough and strong enough that it got on our window shades. I made a mental note to get some new ones at Home Depot.

And then, about half an hour later, the baby was out! There was a terrifying moment when he didn’t say anything. It was a very short moment, because right after that he started screaming. He was fine; the baby was fine. Emily and I looked at each other and laughed. We were so happy and relieved. We couldn’t believe we had managed to do it—that Emily had managed to do it. At home; in our bed from IKEA; in our apartment above a bar. The assistant listened to the baby’s heartbeat again: thump-thump-thump-thump-thump. Thump-thump-thump-thump-thump. Just like that, the missing beat was gone. Thump-thump-thump-thump-thump.

Martine cut the umbilical cord with a pair of surgical scissors and then let me weigh the baby on a little portable scale. Seven pounds, four ounces. Martine filled out some paperwork. Our very helpful doula helped Emily figure out how to place the baby on her breast so that he would be comfortable eating.

We decided to call him Raphael—after my grandmother Ruzya, who had died just a few months earlier; and after Emily’s 25beloved cat Raffles, who had also recently died; and because, in Hebrew, Raphael was rafa (healed) and ‑el (God)—“healed by God.” He had been healed of his heart condition in the moment of his birth. For a while we argued over whether “Raffi” or “Raphy” was the proper spelling of his diminutive—Emily thought Raffi, I thought Raphy—but eventually I gave in. Raffi it was.

While we lay in the bedroom with Raffi, who looked like a little gremlin, Martine and her assistant and the doula cleaned up all the blood and gore and other stuff that had gotten messed up in all the excitement. And then they left. Emily had given birth at 11:18 p.m., and by 3:00 a.m. they were gone. Our apartment was clean and empty. It was a Tuesday night; the whole neighborhood was asleep. But we were not asleep. They had left us with a little baby, and we had no idea what to do.

Zero to Two (The Age of Advice)

S