Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

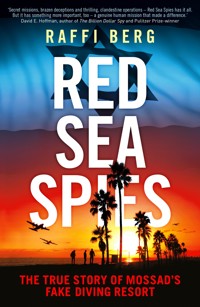

THE TRUE STORY THAT INSPIRED THE NETFLIX FILM THE RED SEA DIVING RESORT. 'Secret missions, brazen deceptions and thrilling, clandestine operations - Red Sea Spies has it all. But it has something more important, too - a genuine human mission that made a difference.' David Hoffman, author of The Billion Dollar Spy '[A] thrilling and meticulous account.' The Times In the early 1980s on a remote part of the Sudanese coast, a new luxury holiday resort opened for business. Catering for divers, it attracted guests from around the world. Little did the holidaymakers know that the staff were undercover spies, working for the Mossad - the Israeli secret service. Providing a front for covert night-time activities, the holiday village allowed the agents to carry out an operation unlike any seen before. What began with one cryptic message pleading for help, turned into the secret evacuation of thousands of Ethiopian Jews who had been languishing in refugee camps, and the spiriting of them to Israel. Written in collaboration with operatives involved in the mission, endorsed as the definitive account and including an afterword from the commander who went on to become the head of the Mossad, this is the complete, never-before-heard, gripping tale of a top-secret and often hazardous operation. 'Red Sea Spies is what really happened. There is none of the Hollywood colouring-in, and yet the book is all the more vivid for it ... part thriller, part dark comedy, all true ... Berg brings out the native drama in an improbable story of a clandestine homecoming.' Spectator

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

vii

In memory of my beloved friend Oliver.

viii

ii

‘The true and most accurate story of the Mossad’s Ethiopian Jewish rescue operation in Sudan.’

Efraim Halevy,Head of the Mossad 1998–2002

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

SELECTED INDIVIDUALS, ORGANISATIONS AND TERMS

PEOPLE

Individuals’ military ranks correspond to the positions they held at the time of their last activity during the operations to evacuate Ethiopian Jews.

Nahum Admoni Director of the Mossad, 1982–89.

Colonel Asaf Agmon Israeli Air Force Hercules squadron commander. Flew on secret airlifts of Jews from Sudan and Ethiopia between 1977 and 1991.

Liwa Youssef Hussein Ahmed Commander of the Sudanese Navy in the early 1980s.

Ferede Aklum Ethiopian Jew who, together with Mossad agent Dani, orchestrated the secret migration to Sudan of thousands of Ethiopian Jews who were then smuggled out to Israel, from 1979 onwards.

Yazezow Aklum Ferede Aklum’s father.

Avrehet Aklum Ferede Aklum’s mother.

Rear Admiral Zeev Almog Commander in Chief of the Israeli Navy, 1979–85.

Apke Mossad employee and first manager of the Arous diving resort, December 1981 to March 1982.

Lieutenant Colonel Ami Ayalon Commander of the Shayetet 13, 1979–81.xii

Colonel Dov Bar Senior officer on board the INS Bat Galim during operation to evacuate Ethiopian Jews from Sudan in March 1982.

Milton Bearden CIA station chief in Khartoum, 1983–85.

Menachem Begin Israeli prime minister, 1977–83. Ordered the Mossad to bring the Jews of Ethiopia to Israel.

Lieutenant Colonel Yisrael Ben-Chaim Israeli Air Force Hercules squadron commander. Flew on secret airlifts of Jews from Sudan and piloted flight which evacuated Mossad agents from Arous in April 1985.

Zimna Berhane Israeli of Ethiopian Jewish origin who succeeded Ferede Aklum as go-between for the Mossad and a clandestine Ethiopian Jewish cell in Gedaref, Sudan, from 1980–81. Served in secret seaborne evacuations of Ethiopian Jews from 1981–83.

Yona Bogale Ethiopian Jewish leader, activist and educator, from the 1950s to 1970s in Ethiopia, then in Israel, until his death in 1987.

Major Ika Brant Israeli Air Force Hercules squadron commander. Served in Israeli Air Force Operations Department, 1982–85. Flew on airlifts of Ethiopian Jews from the desert in Sudan.

Major Ilan Buchris Commander of the INS Bat Galim, 1970s–80s.

Angelo and Alfredo Castiglioni Italian anthropologists and archaeologists. Founded and operated the Arous diving resort from 1974–77.

‘Chana’ Member of the Mossad team and a manageress of the Arous diving resort from late 1983.

Dani Mossad commander and instigator of Operation Brothers. Recruited and led the team of agents who operated the Arous diving resort and carried out secret evacuations of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan by land, sea and air, 1979–83.

Colonel Natan Dvir Israeli Air Force Hercules squadron commander. Flew on secret airlifts of Jews from Sudan (1980s) and Ethiopia (1991).xiii

Dr Jacques Faitlovich Foremost campaigner for Ethiopian Jews in the first half of the 20th century.

Muammar Gaddafi Libyan leader, 1969–2011.

Jacques Haggai Member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort involved in operations in March and May 1982.

Chaim Halachmy Representative of organisations responsible for Jewish immigration to Israel. Helped bring out first groups of Jews from Ethiopia in 1977 and 1978, and connected the Mossad to Ferede Aklum.

Efraim Halevy Overall commander of Operation Brothers at Mossad HQ from 1980 onwards. Instigated Operation Moses in 1984 and facilitated Operation Joshua (Sheba) in 1985. Director of the Mossad from 1998–2002.

Joseph Halévy Professor of Ethiopic at Sorbonne University and first Jewish outsider to make contact with the Jews of Ethiopia (1867).

Major General Yitzhak ‘Haka’ Hofi Director of the Mossad, 1974–82.

Dr Baha al-Din Muhammad Idris Sudanese Minister of Presidential Affairs (sacked by Nimeiri in May 1984).

‘Itai’ Former Israeli Navy commando who served as a diving instructor at the Arous holiday resort from 1983.

Major General David Ivry Commander in Chief of the Israeli Air Force, 1977–82. Instigated the use of airlifts as a way to secretly evacuate Ethiopian Jews from Sudan.

David ‘Dave’ Kimche Head of Mossad division for handling relations with foreign intelligence services. Orchestrated the mission to smuggle Ethiopian Jews to Israel from 1977–81.

Lieutenant Colonel Gadi Kroll Commander of the Israeli Navy commando unit involved in the seaborne evacuation of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan.

Major General Amos Lapidot Commander in Chief of the Israeli Air Force, 1982–87.xiv

Louis Longest-serving member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort mid-1981, participating in evacuations of Ethiopian Jews.

‘ZL’ Swiss-based travel agent who marketed the Arous holiday resort for the Mossad.

Salah Madaneh Head of Sudanese Tourism Corporation in Port Sudan.

Abba Mahari Ethiopian Jewish priest, who is said to have led thousands of followers on an attempted journey from Gondar to Jerusalem in 1862.

Colonel Mohammed Mahgoub Director General of the Sudanese Ministry of Tourism and of the Sudanese Tourism and Hotels Corporation. Leased the Arous holiday village to the European tourism company set up as a front by the Mossad.

Marcel Mossad agent and Dani’s deputy in Sudan. Joined Operation Brothers in late 1980, participating in evacuations of Ethiopian Jews. Served in the operation until late 1984.

Mengistu Haile Mariam Ethiopian ruler, 1977–91.

Abu Medina Caretaker at the Arous diving resort.

Mohammed Head of the secret police in Gedaref.

Colonel Avinoam Maimon Israeli Air Force Base 27 commander in the mid-1980s.

‘Jean-Michel’ UNHCR representative in Gedaref, 1979–81.

Jean-Claude Nedjar ORT project manager in Gondar, Ethiopia, 1978–82.

Jaafar Nimeiri Sudanese president, 1969–85.

‘Noam’ Manager of Neviot (Nuweiba) diving resort in the Sinai. Carried out initial survey of Arous diving resort in May 1981.

Dr Micki Member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort from mid-1982 until late 1984, participating in operations evacuating Ethiopian Jews.

Gil Pas Member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort from May 1982, participating in operations evacuating Ethiopian Jews. xv

Dr Shlomo Pomeranz Deputy head of neurology at Hadassah Hospital, Jerusalem, and Mossad agent. Joined Operation Brothers in Sudan in late 1980, served until 1983, participating in operations evacuating Ethiopian Jews.

‘Ramian’ Businessman in Khartoum who supplied vehicles used by the Mossad team to smuggle Ethiopian Jews.

Rubi Member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort from mid-1981.

Ruth Recruited by the Mossad as head of the ICM office in Khartoum from February 1982.

Uri Sela Mossad agent who joined Operation Brothers in late 1980. Served undercover in Khartoum until April 1985, secretly evacuating Ethiopian Jews through the airport.

Haile Selassie Ethiopian emperor, 1930–74. Overthrown and murdered by the Derg.

Ariel Sharon Israeli defence minister, August 1981 to February 1983.

Gad Shimron Member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort from December 1981, participating in operations evacuating Ethiopian Jews.

Shmulik Head diving instructor at Neviot (Nuweiba) resort and a member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort from mid-1981, participating in operations evacuating Ethiopia Jews.

Shuffa Ethiopian Muslim merchant who delivered messages from Ferede Aklum in Sudan to his family in Ethiopia in 1979.

Omar el-Tayeb Sudanese vice president and head of the State Security Organisation (domestic intelligence agency).

David Ben Uziel (Tarzan) Mossad agent. Participated in operations evacuating Ethiopian Jews out of Sudan. Succeeded Dani as the head of the department in charge of Operation Brothers in October 1983.xvi

‘William’ Member of the Mossad team based at the Arous diving resort who participated in the first naval evacuation of Ethiopian Jews, in November 1981.

Yola Member of the Mossad team and a manageress of the Arous diving resort from September 1982.

‘Yoni’ Agent from the Mossad’s Special Operations Division who made the first survey of the Sudanese coast with Dani and participated in the naval evacuation of Ethiopian Jews in November 1981.

‘Yuval’ Member of the Mossad team based at Arous from April 1983, participating in operations evacuating Ethiopian Jews. Succeeded Dani as field commander.

ACRONYMS, ORGANISATIONS AND TERMS

Alliance Israelite Universelle (AIU) Paris-based international Jewish rights organisation.

American Association for Ethiopian Jews (AAEJ) Pro-Ethiopian Jewish activist group formed in 1974 (dissolved in 1993).

Berare Amharic for ‘Escapees’. Secret cells of Ethiopian Jewish youths in refugee camps in Sudan responsible for smuggling out evacuees at night-time to a waiting Mossad team.

Beta Israel Hebrew for ‘House of Israel’. Name by which the Ethiopian Jewish community has identified itself for generations and now widely used as the proper term of reference.

Canadian Association for Ethiopian Jews (CAEJ) Pro-Ethiopian Jewish activist group formed in 1980 (dissolved in 1992).

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) US secret service.

Committee Men Secret cell of Ethiopian Jewish refugee elders set up by the Mossad team in Sudan to organise evacuation lists and the welfare of Jews in the camps.

Derg Military council which ruled Ethiopia from 1974–87.

Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST) Directorate of Territorial Surveillance. French domestic intelligence agency.xvii

Ethiopian Democratic Union (EDU) Counter-revolutionary movement responsible for attacks against the regime and others, including Ethiopian Jews, from mid- to late 1970s.

Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP) Anti-Derg movement which waged an armed campaign against the regime and other perceived enemies, including ‘Zionist’ Ethiopian Jews in mid-1970s.

Etzel Acronym for Irgun Zvai Leumi (Hebrew for National Military Organisation). Jewish underground group led by future Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin which operated against British forces in Mandate Palestine, 1931–48.

Falashas Amharic for ‘strangers’ or ‘landless people’. Name historically used by outsiders to refer to Ethiopian Jews. Considered derogatory by the Ethiopian Jewish community.

Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) US-based Jewish organisation providing assistance in the resettlement, and in some cases clandestine evacuations, of refugees and Jewish communities in danger.

INS Bat Galim Israeli Navy transport ship used in secret evacuations of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan from 1981–83.

Intergovernmental Committee for Migration (ICM) Organisation responsible for the resettlement of refugees and displaced persons, whose office in Khartoum was set up and operated by the Mossad to move Ethiopian Jews out of the country from 1982.

Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Collective name for the Israeli Army, Navy and Air Force.

Jewish Agency Israeli non-governmental body responsible for helping Jews migrate to Israel.

Mossad Israel’s foreign intelligence agency.

Navco ‘Fake’ tourism company set up by the Mossad for the purposes of operating the diving resort at Arous. xviii

Operation Brothers Umbrella name for a series of clandestine evacuations by land, sea and air of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan to Israel from 1979–85, orchestrated by the Mossad.

Operation Joshua (or Sheba) Secret airlift of the remaining Ethiopian Jews stranded by the abrupt halt of Operation Moses, from Sudan to Israel, on 22 March 1985.

Operation Moses Secret mass airlift of Ethiopian Jews from Khartoum airport to Israel from 21 November 1984 to 5 January 1985.

Operation Solomon Secret airlift by Israel of Ethiopian Jews from Addis Ababa, 24–25 May 1991.

Organisation for Rehabilitation through Training (ORT) Geneva-based Jewish humanitarian organisation, providing assistance to developing communities around the world. Active in Ethiopia’s Gondar region from 1976–81.

Shaldag Elite unit of the Israeli Air Force, deployed in special operations inside enemy territory. Provided protection during airlifts of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan from 1982–84.

Shayetet 13 Hebrew for Flotilla 13. An elite navy commando unit which carried out seaborne evacuations of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan from 1981–83.

Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) Ethiopian rebel movement which fought against the regime from 1975 (eventually helping to overthrow the government in 1991).

Tribe of Dan One of the twelve Biblical tribes of Israel from which, according to one theory, the Ethiopian Jews descend.

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UN refugee agency).

MAPS

The region during the period of Operation Brothers

xx

Sudan’s Red Sea coast

xxi

Arous resortxxii

INTRODUCTION

The story of the spiriting of the Jews of Ethiopia to Israel is one without parallel.

As recently as 1975, the State of Israel, the declared nation state of the Jewish people, denied them the right to settle there.1 Just two years later, Israel began a secret process involving its Air Force, Navy and foreign intelligence service to bring every Ethiopian Jewish man, woman and child it could to the Jewish state. So important was the cause that the people sent to carry it out constantly risked their lives to accomplish it.

In Israel, something profound had changed. For the echelons of the state it was a moment of awakening – but the Ethiopian Jews themselves had never been in slumber. For centuries, arguably millennia, the black Jews of the Highlands had steadfastly clung to the Jewish faith in the face of wars, oppression, invasion, poverty and famine. At the core of their beliefs lay a single driving force – an ancient dream to return to Jerusalem. The Ethiopian Jews maintained throughout the generations that they were Israelites, driven out of the land in biblical times. Their origins are an enigma, and until as recently as the mid-19th century they had survived so cut off from the rest of world Jewry that they thought there was no such thing as white Jews. They might not have survived at all were it not for xxivthe efforts of remarkable individuals, from benevolent French Jews in the late-1800s down to activists in North America a century later, and ultimately courageous decision-makers in Israel who instigated the operation to return them to their ancestral land. Nothing on such a scale had been done before, and it fell to the Mossad – Israel’s much vaunted spy agency – to achieve it.

That is half of it. No such monumental event could have happened without the extraordinary actions, first and foremost, of the Ethiopian Jews themselves. They made it out not from within Ethiopia itself, but from Sudan, a Muslim-majority country tied to the Arab world, blighted by poverty and officially at war with Israel, the very country they were trying to reach. Whether lone souls, or entire villages, Jews walked hundreds of kilometres across inhospitable terrain to get to Sudan – not, according to countless accounts, to escape undeniable hardship and conflict in Ethiopia, but out of a conviction that they were walking to Jerusalem. Many died along the way and the conditions they found themselves in in refugee camps on the other side of the border were immeasurably worse than those which they had left behind. On top of this, it was all done by stealth. They left their homes in the middle of the night, risking arrest, torture and worse if they were caught, as many were, since leaving Ethiopia without permission was treated as a crime. Leaving to get to Israel was treated as treasonous. Even in the refugee camps they hid who they were, lest they be attacked or taken away.

The question arises as to why, then, they headed to Sudan at all. The answer lies in the fact that it was, from 1979, a secret gateway, a pathway to the Holy Land, unlocked by two men – one, an enterprising Ethiopian Jewish fugitive called Ferede Aklum; the other, an exceptional Israeli secret agent called Dani. xxvOne cryptic letter, and an unlikely partnership, changed the course of history for the Jews of Ethiopia, and in many ways that of the State of Israel and the Mossad itself. It is the only operation of its kind, where civilians have been evacuated from another country, that has been completely led by an intelligence agency.

It was through danger and daring that Ferede and Dani laid the foundations for a secret network of Ethiopian Jews and an entire division of the Mossad, backed by naval and air support, to deliver thousands of Jewish refugees to a land they had yearned for for so long. As Dani put it to me in one of our many interviews: ‘It was like two big wheels, two strong wheels, actually met – one was the old Ethiopian Jews’ dream to go back to Zion and Jerusalem, and the other one was the Israeli Jews that came to help them fulfil this – it was the fusion of wheels that was the strength of this operation – that is why nobody ever gave up.’*2

It was also the result of a combination of bravery, ingenuity, subterfuge and guile – perhaps none more so than the ruse used as a years-long cover story by the Mossad to carry out the mission behind enemy lines. With astonishing inventiveness, the team of secret agents led by Dani set up and operated a diving resort on the Sudanese coast, masquerading as hotel staff by day, while smuggling Jews out of the country by night. Even more remarkable was the fact that it was done hand-in-hand with unwitting Sudanese authorities and under the very noses of the guests. How it happened is told in this book, pieced together from accounts of the agents and the people who stayed there themselves.

xxviIn the course of over 100 hours of interviews I conducted with past and present Mossad agents and Navy and Air Force personnel involved in the secret operation, both on the ground and behind the scenes, many made a similar, personal point: that they knew there and then that they were involved in something historic. All would say with modesty that they were ‘just doing their job’ but it was clear they were motivated by something much more visceral than that. More than once, these individuals would use the analogy of the biblical Exodus of the Jewish people who went from bondage in Egypt to redemption in the Promised Land. They felt they were carrying out something similar in the modern age.

The latter day event is often referred to as the ‘rescue’ of the Ethiopian Jews. This, however, is a characterisation which is rejected by the Ethiopian Jews themselves, a perspective which deserves to be acknowledged and respected. They were masters of their own fate. They elected to make the perilous journey, leaving behind their homes and their way of life, in pursuit of the Holy City, losing loved ones in terrible circumstances along the way. For this reason, and in deference to them, I do not describe what took place as a ‘rescue’ in this book.

By its very nature, the Mossad operates in an opaque and clandestine way, which was very much the case when it came to smuggling the Jews out of Sudan. For decades, the details of this operation, which paved the way for the historic mass airlift of Jewish refugees from Sudan, known as Operation Moses, were officially secret.3 The fact that it happened is known; how it happened has not been written about before with the full cooperation of those who commanded and carried it out. Now is a moment in time when the story is surfacing, quite rightly capturing people’s imaginations. It is an exciting tale, but as xxviiwith all intriguing stories about covert activities, it may in time become muddied by half-truths and fictional portrayals. The real story does not need any such embellishment: it is dramatic and astounding in its own right. I chose to write this book for the same reason as those individuals who decided to take me into their trust did so – to document it in a truthful way so it stands as an authentic record of what took place. Some of the contributors have not spoken out about their roles before and none seek public recognition.4 In this book, where there is dialogue it is faithfully reproduced as close to verbatim as possible, based on the recollections of those who were part of these conversations.

This book has taken me on an extraordinary journey of discovery and it has been nothing short of a privilege. I write it in tribute to both the Beta Israel (Ethiopian Jews) and the actions of the Mossad and Israeli armed forces which helped to bring them home.xxviii

Notes

1. Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 15 April 1975.

2. Author interview with Dani, 24 August 2018.

3. Operation Moses was a clandestine airlift by Israel of 6,822 Ethiopian Jews from Sudan between 21 November 1984 and 5 January 1985.

4. Where contributors have requested anonymity, pseudonyms are used in place of real names and appear within inverted commas on first mention outside of direct speech to signify so.

*Zion: a biblical term for Jerusalem and/or the ‘Land of Israel’.

1

CAT AND MOUSE

APRIL, 1985

It was after dark when the knock came on Milton Bearden’s door. He was not expecting visitors and the rapping had an urgency to it, suggesting this was no social call.

Bearden cautiously opened up.

‘We’ve got trouble!’ said one of the three men standing there. Bearden did not recognise them, but he knew who they were.

‘Come in,’ he said instinctively, glancing around as he ushered them inside.

‘Go upstairs. There’s a loft. Get up there and stay out of the way.’

The three men followed his direction and disappeared out of sight.

Bearden knew he suddenly had an emergency on his hands. As he stood considering what to do, one of the men reappeared.

‘Here,’ said the figure, tossing Bearden a set of keys, ‘you’d better get the stuff out of the van.’

Milton Bearden, the CIA’s station chief in Khartoum, had been prepared for such a moment for the past two years. He understood his ‘guests’ were Mossad agents, and that they were on the run.2

In hot pursuit were units of the Sudanese Army, aided by a Libyan hit-squad sent by the country’s mercurial ruler Muammar Gaddafi to hunt down dissidents operating in the city.

The old order had been swept away days earlier when Sudan’s longtime leader and US ally Jaafar Nimeiri was deposed in a popular uprising backed by the Army. A military council was now in charge, President Nimeiri and his acolytes accused of everything from corruption to high treason. Among the allegations was collusion with Israel, with which Sudan was in a formal state of war.1 Now it was time for the new rulers to burnish their credentials among the Arab world and flush out Zionist spies, real or imaginary.

Bearden checked the coast was clear, then went out to the men’s vehicle. It was packed with communications equipment, much to his chagrin. He lugged it all inside the house, hiding it in a back room.

The station chief went upstairs to talk to the men and discuss what to do. The contingency plan had been agreed at a meeting with Mossad officials in August 1983, shortly after he had taken up his post. In the event of a problem, Israeli agents in Khartoum knew to meet Bearden in the arcade of the Meridien Hotel, identifying him by his walking stick with a warthog tusk handle and a .44 Magnum casing tip, or to head to his house in the capital’s New Extension district – in Bearden’s words, ‘at the snap of a finger, if everything starts to fall apart’.

Mossad had been operating secretly in Sudan for years, but owing to the political upheaval, its presence had finally been exposed.

As soon as it took power, the Sudanese military began making sweeping arrests in an anti-Nimeiri drive, purging the 3state security service and detaining hundreds of key figures associated with the ousted government. Among them was Nimeiri’s former Minister of Presidential Affairs, Dr Baha al-Din Muhammad Idris, known as Mr Ten Per Cent on account of the cost of greasing his palm. Purportedly arrested while trying to flee the country with a Samsonite suitcase full of money, Idris is said to have offered his captors information in exchange for clemency.

‘Leave me alone, and I’ll give you something really big,’ he said, according to Bearden, recounting conversations with trusted sources. ‘There’s an Israeli intelligence nest here in town. Arrest them, and you’ll be heroes.’

It did not help Idris. He was later convicted of corruption and sentenced to ten years in jail, but it was enough to put the hit squad on the Israelis’ trail.

Mossad chiefs in Tel Aviv knew they had to get their men out before their pursuers closed in. The question was how. The borders and airport had been closed – dump trucks had been parked on the runways to prevent any aircraft arriving or leaving – and outside telephone lines cut since thousands of protesters had taken to the streets demanding Nimeiri’s removal.

Whichever way, it was not going to happen very quickly, and Bearden’s immediate problem was to keep the men hidden. He employed household staff and could not be sure that they were not passing information to the authorities. The staff had gone for the night but would be back in the morning and inevitably wonder about the unannounced guests.

Bearden decided to pass the Israelis off as US contractors on temporary duty at the embassy, staying with him for the time being. He gave them Dallas Cowboys baseball hats ‘and made sure they looked like Americans’. He also gave them weapons – a 4 Browning Hi-Power 9mm semi-automatic pistol and a 9mm Beretta submachine gun.

‘There was a very active search for these guys going on,’ Bearden recalls, ‘and with my own intelligence assets I was able to monitor pretty closely the planning for this search – where these [Sudanese/Libyan] guys were going to be looking, which quadrant of town. I was able to understand what they were up to as well as they were.’

In the meantime, Bearden, CIA HQ in Virginia and Mossad chiefs were in contact, and they got to work on a plan. With conventional options closed, the men, it was decided, would have to be smuggled out of the country, albeit at great risk.

‘Crates,’ proposed Bearden. ‘What about putting them in crates?’ The idea was perilous and subjected to a ‘very difficult decision-making process’, as one high-ranking Mossad official with intimate knowledge of the discussions remembers. Time was short and after tense debate at Mossad HQ the plan was approved.

The CIA’s technical services set to work on a design.

A few days after the men had turned up at Bearden’s house, another knock came at the door. This time his wife, Marie-Catherine, answered. ‘My name is Pierre. I’m French,’ announced the visitor.

‘Come in quickly,’ replied Mrs Bearden, ‘but I can tell you’re not French – because I am,’ she said. ‘Go into that room and wait.’

‘Pierre’ was in fact another Mossad agent, sent to find out about the other three. ‘There wasn’t much he could do other than come to me,’ recalls Bearden, ‘so now instead of three, we had four.’

Bearden decided it was time to wrong-foot their pursuers. 5‘I knew which areas had just been canvassed for these guys, so it was a safe bet to take them right there,’ he recalls.

He put the four men, dressed in their American garb, in a van and drove them to parts of town which search teams had already scoured. Monitoring the pursuers’ movements, Bearden shuttled the agents between safe houses and his own home, for one or two days at a time, in a tense game of cat and mouse.

Ten days after it was shut down, the airport reopened, and the US embassy put in a request with the Sudanese authorities to allow a resupply plane in. The flight got the go-ahead and a C-141 flew in with stocks of equipment. There was something else on board: the aircraft was carrying the escape kit, and a CIA technician to put it together. Unloaded, the apparatus was taken to the embassy building on Ali Abdul Lattif Street in west Khartoum, where it was assembled.

The boxes were rigged with air tubes and small oxygen generators that could be activated from within as back-up. The plan was to hide the men inside the crates, place the boxes in oversized diplomatic pouches, seal them up and get the ‘cargo’ past Sudanese security to a waiting plane at the airport some 25 minutes’ drive away.

‘There was a 49–51 per cent chance of this working,’ says Bearden. ‘But these men [on their trail] were just not giving up, and they meant harm.’

The following day Bearden and the men, accompanied by two CIA officers and a driver, slipped out of his home before dawn and set off for the embassy. There Bearden and the technician helped the four agents climb into the boxes.

‘They understood and showed no fear,’ he recalls, ‘I patted them on their heads and told them: “God be with you. Be bold, be brave, be strong.”’26

The lids came down. The pouches were tied. It was time to go.

SEPTEMBER, 1973

The tall, slim man walked into the building on Dejazmach Belay Zeleke Road. The flag outside – white with two blue stripes and a star in the middle – signalled he had found the right place.

Ferede Aklum had travelled more than 900 kilometres from his home in Adi Woreva, a Jewish village in the highlands of Tigray, in Ethiopia’s far north, to the Israeli embassy in the capital, Addis Ababa, to get a pass to a new life.3 He had arrived full of hope, but his optimism quickly faded.

Visas to Israel, embassy officials told Ferede, were not issued on the spot. Applicants were required to show proof of their intended travel, such as an air or sea ticket, and that they had sufficient funds to support themselves once they got there. It amounted to several hundred US dollars, beyond the reach of impoverished villagers.

Despite the obstacles, Ferede was single-minded. He travelled back home and set about forging a ticket for a journey by boat to Israel and raising money, supported in his endeavour by his parents.

Ferede’s father, Yazezow, was a well-respected district judge in Indabaguna, a mixed Muslim-Christian town with a small Jewish presence, near Adi Woreva.

An erudite and religious man, he studied both Ethiopian law and the Bible. The Ethiopian Jews were a devout community who considered themselves the descendants of the Jewish people who, according to tradition, stood at the foot of Mount Sinai and received the Ten Commandments, conquered 7Canaan under Joshua and formed the Kingdom of Solomon with its Holy Temple in Jerusalem. Until the latter part of the 19th century, they self-identified not as Jews (ayhud in Amharic – Ethiopia’s official language – historically a derogatory term in Ethiopia) but as ‘Beta Israel’ – House of Israel – or, put simply, Israelites.4

Although Judaism had been part of the fabric of Ethiopia for centuries, non-Jewish Ethiopians (and foreigners) referred to them as falasha, meaning ‘strangers’ or ‘landless people’. The Beta Israel considered this degrading, even though in a religious sense they regarded themselves as living in exile and looked upon Jerusalem as their spiritual home. They spoke not of the Land of Israel (as it is known in the Hebrew Bible) but the Land of Jerusalem. They prayed towards Jerusalem, slaughtered their animals for food while facing in its direction and spoke about the holy city as flowing with milk and honey. Stories about the glory of Jerusalem were passed down from generation to generation, and poetry and songs were written in its praise. ‘Shimela! Shimela!’ Ethiopian Jewish children would sing on catching sight of a stork, as migrating musters headed to the Holy Land, ‘Agerachin Yerusalem dehena?’ – ‘Stork! Stork! How is our country Jerusalem doing?’5

Like his own parents and grandparents before him, Yazezow believed the time would come when, in the words of the prophet Isaiah from the 8th century bc, ‘the Lord will set His hand again the second time to recover the remnant of His people, that shall remain from Assyria, and from Egypt … and from Cush …’6 At the time of Isaiah, Cush corresponded to present-day northern Sudan and possibly beyond, and it was where, according to one theory, Jews resided in ancient times before crossing into what is now Ethiopia.78

Yazezow would tell his own twelve children over and over again of Jerusalem’s splendour, delicately depicting imagined scenes of the city in embroideries with threads of red, yellow and gold.8

With his parents’ blessing, Ferede went back to the embassy. He produced his ‘ticket’ and cash, and got his visa. His hope renewed, Ferede then took a bus 1,200 kilometres north to Eritrea, where he bought a one-way ticket for a sea voyage to the Israeli port city of Eilat. For the 25 year old, it was the culmination of a lifelong dream. He checked into a guesthouse and waited for his boat.

The Beta Israel had heard about Israel’s declaration of independence in 1948 and had danced jubilantly in the streets. There were around that time nascent contacts between Ethiopian Jews and other Jewish communities in the world – but in Israel itself, even by the 1970s, the Ethiopians were not recognised as ‘real’ Jews – neither by the state nor its Orthodox rabbinical establishment. As a result, they did not qualify to settle there under the 1950 Law of Return, which granted Jews anywhere in the world the right to Israeli citizenship.9 In spite of this, a small number of Ethiopian Jews had made it to Israel by boat – some had got through, while others were caught and were turned back.10 Ferede was prepared to take his chance. He had his pass – albeit a tourist visa – and was set to go.

Then two days before he was due to sail, calamitous news broke. Israel had been attacked by Syria and Egypt on the holiest day in the Jewish calendar – Yom Kippur – and was at war. All flights and sailings between Ethiopia and Israel were cancelled. Worse was to come when, some two weeks later, relenting to Arab pressure, Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie severed diplomatic relations with Israel.9

For Ferede it was a catastrophe. He went back home in a state of despair.

The Yom Kippur War, as it would become commonly known, was one of Israel’s most difficult.11 Taken by surprise, the Jewish state sustained heavy losses and struggled to beat back the attacking forces. By the time the fighting ended in a ceasefire twenty days after it started, Israeli troops had advanced to within 101 kilometres of Cairo and 40 kilometres of Damascus. Exhausted, Israel’s sense of invincibility, shored up by its overwhelming victory in the Six Day War just six years earlier, had been punctured.12 The nation had suffered a trauma and although the governing Labor Party was returned to office in elections just two months later, support was slipping. For the first time in Israel’s political history, public opinion began to shift from the left to the right. The left was ideologically split over what to do with territory won from the Arabs in 1967, anti-government demonstrations against the failure of the ruling elite to anticipate the attack in 1973 were growing, and Israel’s ‘Iron Lady’ Golda Meir resigned in April 1974 over the fallout from the war. Her replacement, Yitzhak Rabin, was beset by a series of corruption scandals in the party, and himself resigned weeks before elections in 1977 after it emerged that his wife illegally held a US bank account.13 The conditions were ripe for change, and the polls in May delivered it. Israel witnessed a political earthquake. The country woke up to a new prime minister, and the dawn of a new era.10

Notes

1. ‘Sudan’s Probe of CIA Role in Airlift of Ethiopian Jews’, Washington Post, 20 July 1985.

2. Author interview with Milton Bearden, 29 September 2018.

3. Author interview with Amram Aklum, half-brother of Ferede Aklum, 19 August 2018.

4. Steven Kaplan, The Beta Israel (Falasha) in Ethiopia, New York: New York University Press (1992), pp.164–65.

5. Micha Feldman, On Wings of Eagles: The Secret Operation of the Ethiopian Exodus, Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House Ltd. (2012), pp.38–9.

6. Isaiah 11:11.

7. The precise boundaries of Cush are disputed and some sources contend that it included part of present-day northern Ethiopia.

8. Embroideries by Yazezow Aklum are currently housed in the Israel Museum’s collection of Ethiopian art in Jerusalem.

9. Law of Return (Hok Hashvut), passed by the Knesset on 5 July 1950; amended 23 August 1954 and 10 March 1970. 306

10. Up to 1977, there were officially 269 Ethiopian Israelis, according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), although the actual number of Ethiopian Jews in Israel could be around 100 more than that (see Mitchell G. Bard, From Tragedy to Triumph: The Politics Behind the Rescue of Ethiopian Jewry, Westport: Praeger Publishing (2002), p.48.).

Daniel Gordis, Menachem Begin: The Battle for Israel’s Soul, New York: Schocken Books (2014), p.145.

11. The war is also known as the October War and the Ramadan War.

12. On 5 June 1967 Israel launched a pre-emptive strike against Egypt and Syria, amid signs they were about to attack. A full-scale war broke out, drawing in Jordan on Egypt and Syria’s side. The war lasted for six days. By the end, Israel had driven Egypt out of Gaza and the Sinai, Jordan out of East Jerusalem and the West Bank, and Syria out of most of the Golan Heights. For Israel, it was an historic victory, and for the Arabs an ignominious defeat.

13. ‘Rabin Quits Over Illegal Bank Account’, Washington Post, 8 April 1977.

2

‘BRING ME THE ETHIOPIAN JEWS’

A short, balding man with prominent features who wore distinctive large, heavy-rimmed glasses, Menachem Begin had been leader of the opposition in parliament for 29 years, having contested – and lost – eight previous elections. Now, as head of the right-wing Likud party, he had been swept to power.

Begin was widely perceived as being one of Israel’s founding fathers. A staunch nationalist, he had led one of the most fearsome Jewish underground groups operating against British forces in Palestine, the Irgun Zvai Leumi (National Military Organisation), known by its Hebrew acronym Etzel.1 In the 1940s, the group carried out attacks and reprisals to try to force the British out. Its most notorious attack was on the luxurious King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which housed the British military command, where in 1946 a bombing brought down the southern wing, killing 91 people.2 Begin spent years as a wanted man, and came out of hiding only after the establishment of the State of Israel. He had arrived in Palestine in 1943, escaping the Nazi invasions of Poland and the Soviet Union, but his parents, elder brother and a nephew had not got out and were murdered by the Germans.

Begin’s mentality was shaped by the Nazi Holocaust and the persecution – and defencelessness – of Jews. (He would 12reportedly tell US President Jimmy Carter later: ‘There is only one thing to which I’m sensitive: Jewish blood.’)3 For him, Israel was not just the Jewish homeland, but a sanctuary for Jews under threat anywhere. The bringing of the Jewish diaspora to Israel was a Zionist goal and for Begin a creed. In a transitional meeting with outgoing Prime Minister Rabin and the head of the Mossad, Yitzhak ‘Haka’ Hofi, Begin was briefed on the intelligence agency’s operations. Prime ministers could hire and fire Mossad chiefs, but Begin asked Hofi – who was reportedly prepared to resign – to stay on.4 Begin told him to carry on all planned and active Mossad missions, and to add a new one to the list. ‘Bring me the Jews of Ethiopia,’ he said.5

The fate of Ethiopian Jews had become an issue while Begin was in opposition. In the 1970s, activist groups in the US and Canada, led by the American Association for Ethiopian Jews (AAEJ), spearheaded campaigns to prick public consciousness about the Ethiopian Jewish community and pressure the Israeli government to act. The AAEJ said it forced the issue up the prime minister’s agenda, but this claim is emphatically rejected by Israeli officials in positions of seniority under Begin’s administration.6 According to a high-ranking Mossad figure who dealt with the prime minister personally in connection with the issue at the time, both Begin and Hofi acted out of a deep sense of moral obligation, dismissing the suggestion that they were pressured into it as specious.7

It is true that for decades the Israeli state and (to a lesser extent) the Jewish Agency – a non-governmental body which helped Jewish communities abroad and facilitated immigration to Israel – were at best ambivalent and at worst resistant to doing anything about Ethiopian Jewry. There was among political circles a sense that Ethiopian Jews’ ‘primitive’ way 13of life was incompatible with that led by modern, integrated Israelis, rendering them too problematic and costly to absorb. Golda Meir herself reportedly said of the issue in 1969: ‘They will just be objects of prejudice here. Don’t we have enough problems already? What do we need these blacks for?’8 Even as late on as 1975, the head of the Jewish Agency’s Department of Immigration and Absorption, Yehuda Dominitz, expressed opposition to bringing them to Israel.9

There was also Israel’s relationship with Ethiopia to consider. Ethiopia was part of Israel’s so-called Periphery Doctrine – a policy to forge alliances with non-Arab countries in the region to counter the anti-Israel bloc of Arab states. Ethiopia was strategically important to Israel. It was a Christian-majority country (with a large Muslim minority), which bordered Arab-majority Sudan and sat across the Red Sea from Saudi Arabia and North and South Yemen. Of the countries with a Red Sea coastline, Ethiopia was the only one friendly towards Israel. Crucially, it also bordered the Bab al-Mandab Strait, the 35-kilometre-wide waterway connecting the Red Sea with the Indian Ocean. For Israel, unfettered access through the strait was vital for the import of oil as well as for trade with East Africa, Iran and the Far East.

Israel had fostered links with Ethiopia since the 1950s and did not want to do anything to antagonise Selassie. To make an issue out of its Jews risked stoking demands of their own from the array of other ethnic groups in Ethiopia, a country of such diversity as to have earned the epithet of ‘museo di populi’, or museum of peoples.10 In Ethiopia itself there was no real history of emigration – the few Ethiopians who did leave the country went to study abroad but nearly all returned.11 Among them, hardly any were Jews trying to get to Israel.14

‘There were very few, because the policy of Haile Selassie was “They’re all my sons”,’ recalls Reuven Merhav, a Mossad official seconded to the Israeli embassy in Addis Ababa from 1967–69. ‘He looked at [all Ethiopians] as if he was the great emperor and everyone there was under his wings, and there was no such trend. The Jews knew the Israeli government wouldn’t let them in – the Rabbinical Establishment did not recognise them as Jews – and the Ethiopian government didn’t want to let them out.’12

The advent of Begin, however, changed the trajectory. His motives can only be speculated upon, but it is arguable that he was driven not only by Zionist idealism and an egalitarian approach to Jews regardless of colour, but also by an affinity towards peoples in peril, born out of the tragedy of the Holocaust. In his first act as prime minister, for instance, Begin gave refuge to dozens of Vietnamese people fleeing the aftermath of the Vietnam War, who were picked up in boats in the Pacific Ocean by an Israeli cargo ship. Announcing his decision to the Knesset (Israeli parliament) on his inaugural day in June 1977, Begin evoked the abandonment of Jews to their fate by the nations of the world, saying: ‘Today we have the Jewish state. We have not forgotten [countries’ indifference]. We will behave with humanity.’13

Whatever his rationale, it was clearly important enough to him to make the Ethiopian Jews a priority at a time when Israel had all manner of domestic and foreign challenges to deal with.

It was an unprecedented order for the Mossad. Designed primarily for espionage, sabotage and assassination in defence of the state, the agency was not structured for such a task at that time.15

However, the instruction had been issued by the Prime Minister and it was the Mossad’s duty to carry it out. Begin had ordered Hofi, and Hofi commissioned one of his most experienced officers, David Kimche, to do it. Born in the leafy north-west London suburb of Hampstead, Kimche has been described as a ‘true-life Israeli equivalent of John le Carré’s fictional British spy, George Smiley’.14 He was, according to agents who worked with him, an exceptional person, both professionally and personally. In particular, he knew Africa well, having spent many years there quietly fostering relations for Israel with military chiefs and heads of states (earning himself the nickname among colleagues of ‘the man with the suitcase’).15

From the outset, Kimche, who came from a strongly Zionist family, was convinced of the mission’s virtue and persuaded others of it too. His philosophy, according to a senior operative close to him, was that ‘if you believe in something, there is no obstacle – you will go round, you will go up, down, whatever, you will do it, and that is what Kimche relayed to everyone working for him’.16

By the early 1970s, Israeli projects in Ethiopia in almost every field – military, economic and technical – were extensive and pervasive.17 In fact, a US state department official who served in Ethiopia until 1972 observed that Israelis there ‘were probably more influential than the United States … If you really wanted to get to the Ethiopian government, you went through the Israelis, not the Americans’.18 For the Jewish state, such level of involvement was key to strengthening Ethiopia against subversion by Israel’s regional enemies; for Selassie, Israel was an asset to Ethiopia in its struggle against Arab and Muslim-backed secessionists in Eritrea on its northern frontier.1916

Israeli intelligence reputedly saved Selassie himself from three coup attempts, and compared to the rest of the continent, where leaders had been toppled like dominoes in the post-Second World War period (there had been some 60 coups or attempted coups in Africa since 1946) Ethiopia had been a politically stable ally.20

All that was to dramatically change though in 1973, when the Arab-Israeli war led to a haemorraging of Israel’s relations with African states. Through a combination of Arab pressure and pan-African solidarity, one after the other, African nations severed ties with Israel in October and November of that year.

In a shock to Israel, Ethiopia followed suit. Arab states had threatened to move the headquarters of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), from which Selassie derived much prestige as its figurehead, from Addis Ababa, and his prime minister convinced him to choose relations with the Arab world over the Jewish state. Despite the public rupture, Selassie held out the prospect of resuming diplomatic relations – but it was not to be.21 Less than a year later, in September 1974, he was overthrown by a group of Marxist Army officers (his position made more vulnerable, it has been suggested, by the expulsion of Israeli security advisors).22 The historically sympathetic emperor was replaced by a radical anti-capitalist, anti-religion, pro-Soviet regime, and Ethiopia to Israel looked a lost cause. However, realities were such that the political tumult created an unexpected opportunity.

The new military junta, known as the Derg, inherited the problem of the rebellion in Eritrea and intensified efforts to crush it. Armed uprisings also broke out in other parts of the country and by the end of 1976 the regime was beset by 17insurgencies in all of Ethiopia’s provinces. The Derg turned to Ethiopia’s erstwhile ally, and in December 1975 secretly recalled the Israeli military experts ejected by Selassie.

Even without an embassy, the Mossad had continued to operate an undercover office in Addis Ababa, staffed by a single agent.23 Publicly, it masqueraded as an agricultural development office, its real purpose to preserve a secret but solid contact with the new regime through Israel’s foreign intelligence service. According to high-ranking Mossad officials, it was (officially, at least) known about only by the Ethiopian president, Mengistu Haile Mariam (who violently manoeuvred his way to become head of state in February 1977) and one or two others in the highest echelons.24 This is questionable, though, because it is said that once when the agent was waiting for a meeting with the Ethiopian minister of defence, a Soviet general, chest full of medals, emerged from the minister’s office and acknowledged the waiting man with a Russian-accented ‘Shalom’.25

In July 1977 Ethiopia faced a new battlefront when neighbouring Somalia invaded the eastern Ogaden region, home to predominantly ethnic Somalis. Somalia and the allied Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) made swift territorial gains, putting the beleaguered Ethiopian forces on the back foot.

Ethiopia had previously been a recipient of US military aid, but after Jimmy Carter took office earlier that year, Washington publicly announced cuts in response to Ethiopia’s woeful human rights record. Mengistu retaliated by scrapping a mutual defence assistance treaty and ordered US personnel to leave the country.26 As a result, the US, which had been Ethiopia’s biggest arms supplier, stopped sending weapons.18

Stung by the loss of US military support, Mengistu called the Mossad’s man in Addis Ababa for a meeting. Israeli personnel had already (in 1975) helped set up a 10,000-strong counter-insurgency division (known as Nebelbal, or Flame) to fight the Eritrean rebels, and the Jewish state was supplying crucially needed spare parts for Ethiopia’s US-made weaponry.27 Now Mengistu wanted Israel to significantly step up its military assistance.

He also wanted the Israeli Air Force (IAF) to bomb Somali positions and air-drop supplies to a brigade besieged by Eritrean insurgents.28

The message got back to the Mossad HQ in Tel Aviv. It was picked up by Dani, the deputy head of a department responsible for handling relations with intelligence services in the developing world.

Dani, whose brief included Ethiopia, went to discuss the issue with Kimche, the head of his division.

By now around two months had passed since Begin issued his order, and no Jews had yet been brought out of Ethiopia. Kimche spotted an opening.

‘We can’t give Mengistu everything he wants,’ he said, ‘but we can give him something – and we can ask for Ethiopian Jews in return.’

The two men went to see Hofi in his office on the eleventh floor.

Kimche proposed a meeting with Mengistu. ‘We can discuss what we’re prepared to give him, and what we can get in return,’ he said. Hofi agreed and instructed Kimche to make the trip.

Kimche turned to Dani, ‘Okay, you’re coming with me.’

At that time, Dani, although having risen to a senior position, like many in the Mossad had not been involved with 19this kind of mission before, nor exposed to negotiations with heads of state. Born in Uruguay to French parents, he had been recruited from the Army, where he served as a paratrooper officer, to the Mossad in 1968 when the agency was looking for officers with foreign language skills. Dani spoke Spanish and French fluently, and knew several other languages. Kimche also saw in him someone who, like him, was not afraid to think outside the box, question authority and even rebel against it. For much the same reasons, Dani greatly admired Kimche and considered himself a kind of apprentice to him.

Kimche and Dani flew to Addis Ababa on an unmarked military plane. They went straight from the airport to the presidential palace – formerly Selassie’s seat of power. They entered Mengistu’s office, where they found the president, a translator and the Mossad’s representative.

The atmosphere was businesslike as the group shook hands and sat down. As Dani took his seat, Mengistu made a remark in Amharic.

‘Fidel Castro was sitting there a week ago,’ said the translator, in English.

‘Ah, Fidel Castro!’ responded Dani. ‘I grew up with Che Guevara!’ he said, gesturing with a salute.29 It was an offbeat moment, which made Mengistu laugh, breaking the ice. For the rest of the meeting, Kimche and Mengistu discussed matters, as Dani and the representative observed. (Mengistu broke off with a ‘May I?’ to pocket a box of Israeli matches offered by Dani to light the president’s cigarette.)

The result of the talks was that Israel agreed to send consignments of small arms and ammunition and to lend pilots who would teach the Ethiopian Air Force how to make air drops to the encircled brigade. In exchange, Mengistu would allow 20the planes bringing in the supplies to transport back to Israel a number of Ethiopian Jews, according to a list which Israel would draw up – first and foremost relatives of some of the 300 or so who were already legally there.30

The person nominated to sort this out was Chaim Halachmy, who headed the office of the US-based Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) in Israel. Tunisian-born Halachmy had previous experience in smuggling Jews from one place to another during the North African Jewish immigration to Israel in the early 1950s. He also worked for the Jewish Agency, which had been involved with Jews in Ethiopia for some 25 years, setting up a network of Jewish schools there, teaching them, among other things, Hebrew.31

Isolated from world Jewry for centuries, the Ethiopian Jews had practically no knowledge of the Hebrew language or of mainstream Judaism.32 Though the biblical foundations were the same, the Beta Israel followed a form of the religion which had not evolved with that practiced by Jews in the rest of the world, having branched off perhaps as far back as 3,000 years.

While the Jewish Agency’s purpose was not to promote aliyah