8,63 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

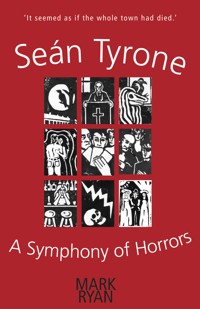

Sean O'Brien left his wife and son in county Tyrone to find work as a collier in the South Wales Valleys. He last posted money and a letter from somewhere called Aberuffern (the mouth of hell). Years later Niamh O'Brien is dying. Her last wish is for Jack, her only son, to discover what became of her father: 'Find him and then I can go to my grave in peace. In brilliantly lyrica prose Mark Ryan employs the black humour and wit of the Welsh and Irish traditions to tell the story of Jack's odyssey from inexperience to manhood. The book is illustrated by a series of woodcuts created by the author.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 114

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

For Louis and Anna

Contents

A Word or Two About My Parents

My name is Jack O’Brien and this is the tale of how I went to find what had become of my father. There are voices here that are not my own but that is in the nature of my story as you will soon discover. I would say that everything here is true as it occurred but I cannot vouch for the accuracy of my own memory or the veracity of what I was told by others. Neither can I always say with certainty what was experienced in actuality or produced by a confused and overstimulated imagination. All I offer is a concatenation of all the above and perhaps something more.

My journey begins on a small farm in County Tyrone. It was here I was born and brought up by my mother. Somewhere in the mists of another land was the father I’d never known. But in the reminiscences of my mother I had grown to love and adore him.

On occasion my mother tells a story of my father playing a game with me. Perhaps it is my first and only memory of him or perhaps it is a memory planted in my mind by my mother’s not always faultless recall of events. He was never a man who, as they say, hung up his fiddle when he came home from the pub. One evening he teaches me this game.

He sits opposite me, three cards in his hand. He shows me the first and says, here’s old Harry, the very Devil himself. Not a good-looking fellow, would you say? And your man here with the meatless chops and holes for eyes, he’ll be Death on his horse come looking for us all. But now we see this fine lady, she’s the High Priestess and if you find her you’ll be safe from the other two lads.

Then my father puts the cards face down – the Devil, the High Priestess and Death in that order. Now all you have to do, he says, is keep your eyes on the lady as I move the cards about a little and then point to where she lies. And if you’re right then sure enough you’ve won the game.

He moves the cards slowly at first then faster and back to slow again before setting them down. I have not taken my eyes from the lady at any time. Now point, he says, so I point at the card without any hesitation. My father turns it over and sighs. So it’s to the Devil you’re going, my old lad.

But as I said, this may not be my memory but a phantasm of my mother’s imagination.

Here is my mother, lying on her deathbed. She has lain there the last seven years since the doctor advised her to take things easy after a minor fall.

‘Son, I am passing from this world and I have nothing to leave you but our few old cows and the government money. And one more thing. Take this locket. It has a picture of your own father. He crossed the water promising he’d send some money home, and he did so. For a month or so, he did so. But then the money stopped and I’ve heard hide nor hair of him since. Take this locket, Jack. It’s all I have of that lovely man aside from you, my beautiful son. Take the locket, Jack. Cross the water and find what became of the git.’

My mother is suddenly galvanised by a shock of pain. She washes a few pills down with whatever is in the glass on her bedside table.

‘You go with my blessing and that of the Holy Mother Church, God curse the bitch for what has come upon me.’

She crosses herself hastily and sends a fearful glance to the crucifix that hangs on the wall.

‘The last place I had the money from was in the Welsh Valleys. Somewhere called Aberuffern. I’ve written it down on this bit of paper. But that’s neither here nor there. There’s five hundred pounds I give you. Take it. I’ve scrimped and scraped and starved you my boy to have it. Take it Jack. My only, lovely boy. Cross the water and find what happened to your father, only man I ever loved aside from you, my dear and handsome son. Find your father, the git.’

Again a wave of pain courses through her skinny old body and she swallows a few more pills.

‘Find him and and then I can go to my grave in happiness and peace. Send me a postcard, will you? You’ll send me a card from Aberuffern?’

My mother opens the locket and passes it to me. I notice he has a gold tooth and point it out.

‘Your father always said a man should wear his wealth in his mouth. He was a handsome lad and kind to me when he was about. You see, he has your aspect about him.

‘Now find him, my wondrous son. Cross the sea and bring him home before Death takes claim on me.’

I take my mother’s locket and her five hundred pounds and her piece of paper. I wasn’t afraid of her dying while I was gone, because I knew she’d never be granted that blessed oblivion until she knew the truth of what had become of my father.

The Song of the Peri

There I was a girl

In my dress I’d

Shimmer and twirl

Incensed by life

Until one day my innocence

Was taken away

I can’t remember

Still

Perhaps tomorrow I will

The Landlord of the Deryn Du

Oh, I’m an old lad I am

You’ll never see a lad like me

I could tell a tale

And it would chill your blood right to the bone.

That Seán Tyrone I knew full well

He had his way with that poor girl

Hanged her father too

And stole away his pub the Deryn Du.

The Ballad of Seán Tyrone

Gareth Miles lived with his daughter in a few rooms above a small public house in Aberuffern. He was proud of the Deryn Du and in his mind the single bar with its faithful band of regular drinkers was his living room, and its kitchen his kitchen, although he offered the customers little provision beyond ham rolls, meat pies and Scotch eggs. The brewery had occasionally put a little pressure on him to introduce ‘improvements’, but he resisted their suggestions in a polite but firm manner. Their ideas of what constituted a traditional pub in this day and age were not his and lay aslant to what he saw about him every morning when he came downstairs to prepare for lunchtime opening. The Deryn Du might not be bright but it was always clean (thanks to his daughter’s efforts) and the beer was well kept and the bar well stocked. Gareth Miles knew his trade and was happy in his place as publican beneath the flaking but picturesque sign of the black bird.

There was but one fly in his soup and he was a young man who Gareth suspected of making a play for his daughter. He had nothing against the Irish or colliers in general; after all they kept the till bell chiming and the boy was polite and sober enough even at closing time, but Gareth had always nursed the ambition that his daughter would marry a professional man when the time came.

Whenever he put forward his views regarding this subject, she laughed.

‘So where would I meet one of these professional men? Not here in Aberuffern, that’s for certain. The doctor is married with four young children and Mr Roberts the teacher must be three times my age if not more. And as for Reverend John, would you really expect me to spend the rest of my days with a man like that?’

Gareth had to concur with her on this point. The Reverend had strict views on the taking of strong drink and often preached teetotalism from the pulpit of the Methodist chapel. More than once Gareth had felt that these diatribes had been aimed directly at himself and had skulked back to the Deryn Du half in shame and half in anger.

‘I still say it would be best to bide your time until a suitable opportunity presents itself,’ he said. ‘I’ve nothing against the local lads or even against the majority of incomers for they are a necessary evil to be borne should Aberuffern prosper, but surely the daughter of the Deryn Du can aim higher in her choice of partner and provider.’

Here she would always smile a light-hearted rebuke to his pomposity.

But every night there was the boy on a stool at the bar, leaning on the counter and engaged in conversation with his daughter as she polished the glasses and pulled the pumps. He wished he could follow their discussions, but he loved his daughter and did not want to drive her into the arms of a stranger by appearing to interfere in her business.

One day Gareth was surprised when the Irish lad walked into the Deryn Du just as he was preparing to close the bar for the afternoon. He had never seen the boy come in for a drink this early in the day.

‘We’re just about to close,’ he said. ‘And if it’s my daughter you’re after she’s away.’

‘I know. At her aunt’s for a few days,’ said the boy. ‘She told me. It’s you I was hoping to have a few words with. In confidence, you understand.’

‘I’ve my customers to attend to.’

The boy looked around the bar. There was no one but an old man with an inch of beer warming in a half-pint glass. The boy took the glass and knocked back the dregs before replacing it on the table.

‘Off you go, Grandpa,’ said the boy. ‘It’s time for your afternoon nap and besides I have business with your man here.’

‘Now look here,’ said Gareth, but the boy was already bolting the door behind the old man.

‘It’s your daughter I’m here to discuss, Mr Miles. As you have probably seen yourself over the last few months we’ve been getting along fine and I was thinking to myself that it’s time to put myself forward. And taking you for a respectable gentleman of the old school I know the right thing to do is ask your blessing before I take any step that might cause you offence.’

‘What are you talking about?’ said Gareth.

‘I’m going to ask your daughter to marry me.’

Gareth made no reply but came around from the counter to collect the empty glass from the table. He wiped the surface with a damp bar towel, unbolted the door and held it open.

‘As I said, we’re closed.’

‘I’ll take that for a no then, shall I? What is it? Am I not good enough for a barman’s daughter? Are you afraid I’d bring down shame on your pintpot family? Afraid of the pitter-pat of peat-kicking Paddy feet about the place? What makes your daughter too good for the likes of me, Mr Miles?’

The landlord stared at the boy for a few moments before giving his answer.

‘It’s not that you earn your living with your hands or that, as I suspect, you own little more than the clothes you stand up in, or even that you are an Irishman and a Papist. I pride myself on being as open-minded as any man must be to open the doors of his home to the public. But there is one thing that shows me I must forbid you any further contact with my daughter.’

‘And what is that?’

‘The gold tooth you have set in the front of your mouth for all the world to see. It shows me that you are no gentleman but a base and vulgar upstart. It shows me that you came from nothing, have nothing and will amount to nothing. And you would like me to give my daughter to a rogue like you?’

The young man held his eye steadily.

‘What is not given to me freely I shall take.’

‘Get out. I don’t wish to see you here again; you are barred from the Deryn Du. It is my privilege as landlord.’

The young man nodded his head and left in silence.

He did not return to the pub that evening and Gareth, who had been left a little shaken by the exchange, felt that the matter was ended and began to relax into his nightly role as an amicable and indulgent host. The hour came for him to call time on his customers and he had come from behind the counter to bolt the door when it was kicked open by the young man’s booted foot. He stood in the frame with the moonlight behind him and a rope slung around his neck.

‘What do you think you’re doing here, you young hoodlum?’ said Gareth. ‘You are barred from these premises.’