4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Shackleton Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1920, tired of the lecture circuit, Sir Ernest Shackleton began to consider the possibility of a last expedition. He thought seriously of going to the Beaufort Sea area of the Arctic, a largely unexplored region, and raised some interest in this idea from the Canadian government. With funds supplied by former school friend John Quiller Rowett, he acquired a 125-ton Norwegian sealer, named Foca I, which he renamed Quest. Despite his harrowing experience recounted in South, the lure of Antarctica was too strong for Shackleton to resist, so he started his fourth and final trip in the ill-suited Quest in 1921. But when Shackleton died suddenly in South Georgia, Frank Wild took charge of what remained, resulting in this eyewitness account of the famous Arctic explorer’s final expedition.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Shackleton's Last Voyage

Frank Wild

Published by Shackleton Press, 2022.

Copyright

Shackleton's Last Voyage: The Story of the Quest by Frank Wild. First published in 1923. Revised edition with annotations published 2022 by the Shackleton Press. All rights reserved.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

1 - Inception

2 - London to Rio de Janeiro

3 – Rio to South Georgia

4 – Death of Sir Ernest Shackleton

5 - Preparations in South Georgia

6 – Into the South

7 - The Ice

8 – Elephant Island

9 – South Georgia (Second Visit)

10 – The Tristan Da Cunha Group

11 – Tristan Da Cunha

12 – Tristan Da Cunha (continued)

13 – Diego Alvarez or Gough Island

14 – Cape Town

15 – St. Helena-Ascension Island-St. Vincent

16 – Home

Further Reading: South! The Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition 1914-1917

1 - Inception

After the finish of the Great War, which had employed every able-bodied man in the country in one way or another, Sir Ernest Shackleton returned to London and wrote his famous epic “South,” the story of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. Before it was finished, he had again felt the call of the ice, and concluded his book with the following sentence: “Though some have gone, there are enough to rally round and form a nucleus for the next expedition, when troublous times are over, and scientific exploration can once more be legitimately undertaken.”

For many years he had had an inclination to take an expedition into the Arctic and compare the two ice zones. He felt, too, a keen desire to pit himself against the American and Norwegian explorers who of recent years had held the foremost position in Arctic exploration, to win for the British flag a further renown, and to add to the sum of British achievements in the frozen North.

There is still, in spite of the long and unremitting siege which has gradually tinted the uncoloured portions of the map and brought within our ken section after section of the unexplored areas, a large blank space comprising what is known as the Beaufort Sea, approximately in the centre of which is the point called by Stefansson the “centre of the zone of inaccessibility.” It was the exploration of this area that Sir Ernest made his aim. In addition he felt a strong desire to clear up the mystery of the North Pole, and forever settle the Peary-Cook controversy, which did so much to alienate public sympathy from Polar enterprise.

It is characteristic of him that before proceeding with any part of the organization he wrote first to Mr. Stefansson, the Canadian explorer, to ask if the new expedition would interfere with any plan of his. He received in reply a letter saying that not only did it not interfere in any way, but that he (Stefansson) would be glad to afford any help that lay in his power and put at his disposal any information which might prove valuable.

Sir Ernest’s plans were the result of several years of hard work with careful reference to the records of previous explorers, and his organization was remarkable for its completeness and detail.

The proposed expedition had an added interest in that the whole of his Polar experience was gained in the Antarctic. It met with instant recognition from the leading scientists and geographers of this country, who saw in it far-reaching and valuable results. The Council of the Royal Geographical Society sent a letter which showed their appreciation of the importance of the work, and expressed their approval of himself as commander and of the names he had submitted as those of men eminently qualified to make a strong personnel for the expedition.

Sir Ernest Shackleton was fortunate in securing the active co-operation in the working out of his plans of Dr. H. R. Mill, the greatest living authority on Polar regions.

The scheme, however, was an ambitious one, and was likely to prove costly.

The period following the end of the war was perhaps not a suitable one in many ways to commence an undertaking of this nature, for Sir Ernest had the greatest difficulty in raising the necessary funds. In this country he received the support of Mr. John Quiller Rowett and Sir Frederick Becker.

Feeling that the work of exploration and the possible discovery of new lands in what may be called the Canadian sector of the Arctic was likely to be of interest to the Canadian Government, he visited Ottawa, where he was in close touch with many of the leading members of the Canadian House of Commons. He returned to this country well pleased with his visit, and stated that he had obtained the active co-operation of several prominent Canadians and received from the Canadian Government the promise of a grant of money.

He was now in a position to start work, and immediately threw himself into the preparation of the expedition. He got together a small nucleus of men well known to him, including some who had accompanied him on the Endurance expedition, designed and ordered a quantity of special stores and equipment, and bought a ship which cost as an initial outlay £11,000. Dr. Macklin was sent to Canada to buy and collect together at some suitable spot a hundred good sledge-dogs of the “Husky” type.

It would be impossible to convey an accurate idea of the closely detailed work which is involved in the preparation for a Polar expedition. Much of the equipment is of a highly technical nature and requires to be specially manufactured. Everything must be carried and nothing must be forgotten, for once away the most trivial article cannot be obtained. Everything also must be of good quality and sound design; and each article, whatever it may be, must function properly when actually put into use.

At what was almost the last moment, whilst preparations were in full swing, the Canadian Government, being more or less committed to a policy of retrenchment, discovered that they were not in a position to advance funds for this purpose, and withdrew their support. This was a great blow, for it made impossible the continuance of the scheme.

In the meantime the bulk of the personnel had been collected, some of the men having come from far distant parts of the world to join in the adventure, abandoning their businesses to do so. Some of us, knowing of the scheme, had waited for two years, putting aside permanent employment so that we might be free to join when required; for such is the extraordinary attraction of Polar exploration to those who have once engaged in it, that they will give up much, often all they have, to pit themselves once more against the ice and gamble with their lives in this greatest of all games of chance. Yet if you were to ask what is the attraction or where the fascination of it lies, probably not one could give you an answer.

Sir Ernest Shackleton received the blow with outward equanimity, which was not shaken when, with the decision of the Canadian Government, the more timorous of his supporters also withdrew. Always seen at his best in adverse circumstances, he wasted no time in useless complainings, but started even at this eleventh hour to remodel his plans.

Nevertheless, the situation was a very difficult one. He had committed himself to heavy expenditure, and what weighed not least with him at this time was his consideration for the men who had come to join the enterprise. At this critical point Mr. John Quiller Rowett came forward to bear an active part in the work, and took upon his shoulders practically the whole financial responsibility of the expedition. The importance of this action cannot be too much emphasized, for without it the carrying on of the work would have been impossible.

Mr. Rowett had a wide outlook which enabled him to take a keen interest in all scientific affairs. Previous to this he had helped to establish the Rowett Institute for Agricultural Research at Aberdeen, and had prompted and given practical support to researches in medicine, chemistry and several other branches of science. His many interests included geographical discovery, and he saw clearly the important bearing which conditions in the Polar regions have upon the temperate zones. He saw also the possible economic value of the observations and data which would be collected.

His name must therefore rank amongst the great supporters of Polar exploration, such as the brothers Enderby, Sir George Newnes and Mr. A. C. Harmsworth (afterwards Lord Northcliffe).

Mr. Rowett’s generous action is the more remarkable in that he was fully aware in giving this support to the expedition that there was no prospect of financial return. What he did was done purely out of friendship to Shackleton and in the interests of science. The new expedition was named the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition, and announcement of it was received by the public with the greatest interest.

As it was now too late to catch the Arctic open season, the northern expedition was cancelled, and Sir Ernest reverted to one of his old schemes for scientific research in the South, which again met with the approval of the chief scientific bodies.

This change of plans threw an enormous burden of work not only upon Sir Ernest, but also upon those of us who formed his staff at this period, for we had little time in which to complete the preparations. Dr. Macklin was recalled from Canada, for under the new scheme sledge-dogs were not required.

The programme did not aim at the attainment of the Pole or include any prolonged land journey, but made its main object the taking of observations and the collection of scientific data in Antarctic and sub-Antarctic areas.

The proposed route led to the following places: St. Paul’s Rocks on the Equator, South Trinidad Island, Tristan da Cunha, Inaccessible Island, Nightingale and Middle Islands, Diego Alvarez or Gough Island, and thence to Cape Town.

Cape Town was to be the base for operations in the ice, and a depot of stores for that part of the journey would be formed there. The route led eastward from there to Marion, Crozet and Heard Islands, and then into the ice, where the track to be followed was, of course, problematical, but would lead westwards, to emerge again at South Georgia.

From South Georgia it led to Bouvet Island, and back to Cape Town to refit. From Cape Town, the second time, the route included New Zealand, Raratonga, Tuanaki (the “Lost Island”), Dougherty Island, the Birdwood Bank, and home via the Atlantic.

The scientific work included the taking of meteorological observations, including air and sea temperatures, kite and balloon work, magnetic observations, hydrographical and oceanographical work, including an extensive series of soundings, and the mapping and careful charting of little-known islands. Search was to be made for lands marked on the map as “doubtful.” A collection of natural history specimens would be made, and a geological survey and examination carried out in all the places visited. Ice observations would be carried on in the South, and an attempt made to reach and map out new land in the Enderby Quadrant. Photography was made a special feature, and a large and expensive outfit of cameras, cinematograph machines and general photographic appliances acquired.

The Admiralty and the Air Ministry co-operated and materially assisted by lending much of the scientific apparatus. Lieut. Commander R. T. Gould, of the Hydrographic Department, provided us with books and reports of previous explorers concerning the little-known parts of our route, and his information, gleaned from all sources and collected together for our use, proved of the greatest value.

It was decided to carry an aeroplane or seaplane to assist in aerial observations and to be used as the “eyes” of the expedition in the South. Flying machines had never before been used in Polar exploration, and there were obvious difficulties in the way of extreme cold and lack of adequate accommodation, but after consultation with the Air Ministry it was thought possible to overcome them. The machine ultimately selected was a “Baby” seaplane, designed and manufactured by the Avro Company.

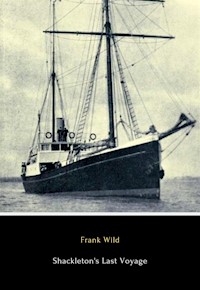

One of the first things done by Sir Ernest Shackleton in preparing for the northern expedition had been the purchase of a small wooden vessel of 125 tons, named the Foca I. She was built in Norway, fitted with auxiliary steam-engines of compound type and 125 horsepower. She was originally designed for sealing in Arctic waters, the hull was strongly made, and the timbers were supported by wooden beams with natural bends of enormous strength. The bow was of solid oak sheathed with steel. Her length was 111 feet, beam 23 feet, and her sides were 2 feet thick. Her draught was 9 feet forward and 14 feet aft. She was ketch-rigged, and was reputed to be able to steam at seven knots in still water and to do the same with sail only in favourable winds.

At the happy suggestion of Lady Shackleton she was re-named the Quest.

Sir Ernest received what he considered the greatest honour of his life. The Quest as his yacht was elected to the Royal Yacht Squadron. Perhaps a more ugly, businesslike little “yacht” never flew the burgee, and her appearance must have contrasted strangely with the beautiful and shapely lines of her more aristocratic sisters.

She was brought to Southampton in March 1921 and placed in the shipyards for extensive alterations. The work was greatly impeded by the strike of ship workers, the general coal strike which occurred at that time, and by difficulties generally with labour, which was then passing through a very critical period.

It had been intended to take out the steam-engines and substitute an internal combustion motor of the Diesel type, but owing to the difficulties mentioned this had to be abandoned, and on the advice of the surveying engineer in charge of the work the old engines were retained. The bunker space was readjusted at the expense of the fore-hold, allowing a carrying capacity of 120 tons of coal, and giving a steaming radius which, with economy and use of sail, was estimated at from four to five thousand miles.

This work was in process when it became necessary to alter the plans of the expedition, and Sir Ernest realized that the Quest, which had been considered eminently suitable for the northern scheme, was not so well adapted for the long cruise in southern waters. It was impossible at this stage to change the ship, but further alterations were made on deck and in the rigging generally to adapt her for the new conditions.

Two yards were fitted, a topsail yard, 39 feet in length, and a foreyard to carry a large squaresail, 44 feet in length. The mizen-mast was lengthened to give a greater clearance to the wireless aerials. The existing bridge was enlarged, carried across the full breadth of the ship, and completely enclosed with windows of Triplex glass. The roof formed an upper bridge open to the air. To improve the accommodation, which was inadequate, a deckhouse, 12 feet by 20 feet, was erected on the foredeck. It contained five rooms: four small cabins, and a room for housing hydrographical and meteorological instruments. New canvas and running gear was fitted throughout, and no expense spared to make her sound and seaworthy. Mr. Rowett was absolutely insistent that everything about the ship must be such as to ensure her safety and the safety of all on board in so far as it was humanly possible. To everything in connection with the ship herself Sir Ernest, as an experienced seaman, gave his personal attention. The work of the engine-room, which, as he was not an engineer, he was not able to supervise directly, was entrusted to a consulting engineer.

The Quest, though strong and well equipped, was small, and consequently accommodation generally was limited and living quarters were somewhat cramped. The forecastle was fitted as a small biological laboratory and geological workroom. In it were a bench for the naturalist and numerous cupboards for the storing of specimens. Leading from it on one side was a small cabin with two bunks for the naturalist and photographer respectively, and on the other was the photographic dark room.

The amount of gear placed aboard the ship was large, and the greatest ingenuity was required to stow it satisfactorily.

Two wireless transmitting and receiving sets, of naval pattern, were installed under the immediate supervision of a wireless expert, kindly lent to us by the Admiralty. The current for them was supplied by two generators, one a steam dynamo producing 220 volts, and a smaller paraffin internal-combustion motor producing 110 volts. The Quest being a wooden vessel, there was great difficulty in providing suitable “earthing.” For this purpose two copper plates were attached to either side of the ship below the water-line.

The more powerful of these sets was never very satisfactory, and we ultimately abandoned its use. The smaller proved entirely satisfactory for transmitting at distances up to 250 miles. The receiving apparatus was chiefly of value in obtaining time signals, which are sent out nightly from nearly all the large wireless stations, and which we received at distances up to 3,000 miles. By this means we were frequently able, whilst in the South, to check our chronometers; but atmospheric conditions in those regions were very bad, and by producing loud adventitious noises in the earpieces interfered so much with the clarity of sounds that the obtaining of accurate signals was generally impossible.

A Sperry gyroscopic compass was installed, the gyroscopic apparatus being placed in the deck-house, with repeaters in the enclosed bridge and on the upper bridge. The dials were luminous, so that they could be read at night. This apparatus has the advantage that it is independent of immediate outside influences. It is usually supposed that at 65° north or south it ceases to be effective, but we found that the directive force was still sufficient at 69° south. It is interesting to note that this compass was designed by a German scientist to enable a submarine to reach the North Pole. It has been of the greatest use to ships in a general way, but for the one specific purpose for which it was designed it proved to be useless owing to the loss of directive power at the Poles. We found that bumping the ship through ice caused derangement, and as the compass took several hours to settle down again to normal, it proved ineffective whilst we were navigating through the pack.

Fitted into the enclosed bridge and looking forward were two Kent clear-view screens. They were electrically driven. They proved, when running, to be absolutely effective against rain, snow or spray.

The ship was fitted throughout with electric lighting, including the navigating lights. Whilst in the South, however, the necessity for economy of fuel forbade the use of electricity and we had recourse to oil lamps. As we were then completely out of the track of shipping, navigating lights were not used.

Two sounding machines were installed, one an electrically-driven Kelvin apparatus for depths up to 300 fathoms. To obtain accurate soundings whilst the ship was under way, the sinker was fitted to carry sounding tubes, and had also an arrangement for indicating the nature of the bottom, whether rock, shingle or sand. For deep-sea work we had a Lucas steam-driven machine, which was affixed to a special platform on the port bow and supplied by a flexible tube from the steam pipe feeding the forward winch. This apparatus registered depths to four miles. Sounding with it was often difficult on account of the swell and the liveliness of the Quest, but the machine itself gave every satisfaction. The wire used with the Lucas machine was Brunton wire in coils of 6,000 fathoms, diameter .028, weight 12.3 lbs. per 1,000 fathoms, with a breaking strain of 200 lbs.

The meteorological equipment included:

Screens, containing wet and dry bulb thermometers, placed in exposed positions on the upper bridge.

One large screen, containing hair hygrograph, standard thermometer and thermograph.

(The heavy seas which broke over the ship and flung sprays over the upper bridge greatly interfered with the efficient working of these instruments by encrusting them with salt, and necessitated constant cleaning.)

Hydrometers, for determining the specific gravity of sea-water, which gives a measure of the total salinity.

Sea-thermometers, for determining the surface temperatures of the sea-water.

Marine pattern mercury barometer.

Aneroid barometers, checked daily from the mercury barometer, in case the latter should be broken.

Barograph, to obtain continuous records of the air pressure.

For upper-air work four cylinders of hydrogen and several hundred pilot balloons were taken. (These latter were sent up on many occasions from the ship, but the Quest proved to be so lively that it was impossible to keep them in the field of view of a telescope or even of field-glasses.)

All the instruments were very kindly lent to us by the Meteorological Section of the Air Ministry, and were of standard make and pattern.

We carried a good set of sextants, theodolites, dip circles and other accurate surveying instruments.

Several chronometers of different makes and patterns were placed aboard. Two of them, specially rated for us by Mr. Bagge, of the Waltham Watch Company, gave excellent results and, in spite of the violent motion of the ship and the difficulty of keeping a uniform temperature, maintained a remarkably even rating.

The medical equipment was designed for compactness and all-round usefulness.

Sledges, harness, warm clothing, footgear and an amount of scientific equipment were forwarded to Cape Town and warehoused to await the arrival of the Quest.

The greatest difficulty was experienced in the housing of the seaplane, but, after dismantling wings and floats, room was eventually found for it in the port alleyway, which it almost filled.

Sir Ernest Shackleton, as has already been said, in choosing his personnel selected first of all a nucleus of well-tried and experienced men who had served with him before, appointing me as second in command of the expedition. They included Worsley, Macklin, Hussey, McIlroy, Kerr, Green and McLeod. Applications for the remaining posts came in thousands, and many women wrote asking if a job could be found for them, offering to mend, sew, nurse or cook.

Two other men with previous experience were obtained: Wilkins, who served with the Canadian Arctic Expedition under Stefansson, and Dell, who had served with Captain Scott in the Discovery, and was thus known to Sir Ernest Shackleton and myself. Lieut. Commander Jeffrey, an officer of the Royal Naval Reserve, who had served with distinction during the war, was appointed navigating officer for the ship. Major Carr, who had gained much experience of flying as an officer of the R.A.F., was appointed in charge of the seaplane.

A geologist was required, the selection falling upon G. V. Douglas, a graduate of McGill University, whom Sir Ernest had met in Canada.

Mr. Bee Mason was appointed photographer and cinematographer.

Amongst the remainder there was need of a good boy. Sir Ernest conceived the idea of throwing the post open to a Boy Scout, and the suggestion was taken up with the greatest enthusiasm by the Boy Scout organization. The post was advertised in the Daily Mail, and immediately a flood of applications poured in from every part of the country. These were finally filtered down to the ten most suitable, and the applicants were instructed to assemble in London, the Daily Mail making the necessary arrangements and defraying the costs. These ten boys all had excellent records, and Sir Ernest, in finally making his selection, was so embarrassed in his choice that he selected two. They were J. W. S. Marr, an Aberdeen boy, and Norman E. Mooney, a native of the Orkneys.

There remained but three places to fill: C. Smith, an officer of the R.M.S.P. Company, was appointed second engineer; P.O. Telegraphist Watts, wireless operator; and Eriksen, a Norwegian by birth, was taken on as harpoon expert.

Sir Ernest, in order fully to carry out his programme, was anxious to leave England not later than August 20th, but owing to a general strike of ships’ joiners, dilatory workmanship and other unavoidable causes, the sailing was postponed well beyond that date.

At length all was ready; food stores and equipment, which included not only the highly technical and specialized Antarctic gear, but also such minute details as pins, needles and pieces of tape, were placed on board, and the ship was ready for sea.

The new expedition had been organized, equipped and got ready for departure all within three months. There are few who will realize what this means. No other man than Sir Ernest would have attempted it, and no other could have accomplished it successfully. It was, as he often said himself, only through the staunch support and active co-operation of Mr. Rowett, who aided and encouraged him throughout this period, that he was able to leave England that year. Postponement at such an advanced stage was impossible, and would have meant the total abandonment of the expedition. We left London finally on September 17th, 1921.

2 - London to Rio de Janeiro

We dipped our ensign in a last farewell to London as we passed out from St. Katherine’s Dock, and turned our nose down-river for Gravesend, a tiny vessel even amongst the small shipping which comes thus far up the river. We were accompanied on this part of our journey by Mr. Rowett, who had taken a keen personal interest in everything connected with the expedition. Enthusiastic crowds cheered us at the start, and everybody we met wished us “Good luck and safe return.” The ensign was kept in a continuous dance answering the bunting which dipped from the staffs of every vessel we met. Ships of many maritime nations were collected in this cosmopolitan river, and these, too, joined in wishing success to our enterprise.

At Gravesend Mr. Rowett left us, and Sir Ernest returned with him to London with the object of rejoining at Plymouth. A strong north-easterly wind was blowing, and we lay for the night off Gravesend. In the small hours of the morning we were startled from sleep by the watchman crying, “The anchor’s dragging!” and turned out to find that we were bearing down on a Thames hopper that was moored nearby. The Quest would not answer her helm, and before we were able to bring her up she had fouled the stays of the hopper with her bowsprit. Pajama-clad figures leapt from their bunks, and in the dim light presented a curious spectacle. Two or three of our men jumped on to the deck of the hopper, and by loosening a bolt succeeded in letting go one of her stays, when we swung free.

Kerr rapidly raised a sufficient pressure of steam in the boilers to get the engines going, and we soon regained control.

We brought up with our anchor, which had been acting as a dredge, the most amazing collection of stuff, which gave an interesting sidelight on the composition of the Thames floor.

No damage was received beyond a chafe to the bowsprit. We were anxious, however, to leave with everything in good order, and so proceeded to Sheerness Dockyard, where a new spar was put in for us by the naval authorities with a promptness and dispatch that contrasted strongly with the dilatory methods employed previously in the shipyards.

We had an exceptionally fine trip down Channel under the pilotage of Captain F. Bridgland, who was an old friend of ours, having taken the ship from Southampton to London.

We reached Plymouth on the 23rd, and were joined there by Sir Ernest Shackleton and Mr. Gerald Lysaght, a keen yachtsman, who had been invited to accompany us as far as Madeira. The Boss brought with him an Alsatian wolf-hound puppy, a beautiful well-bred animal with a long pedigree, which had been presented to him by a friend as a mascot. “Query,” as he was named, quickly became a fast favourite with all on board. Mr. Rowett also came from London to see us off, and we had with him a last cheery dinner. He was very popular with all of us, for in addition to his support of expedition affairs he had taken a personal interest in every member of the company.

On the 24th we steamed out into the Sound and moored to a buoy, where the ship was swung and the compasses adjusted by Commander Traill-Smith, R.N., who kindly undertook this important work. The Admiralty tug used to swing the Quest accentuated her smallness, for she was many times our size and towered high above us.

This task completed, we put out to sea, pleased, as Sir Ernest Shackleton said at the time, to be making our final departure from a town that has ever been associated with maritime enterprise.

The following extracts are from Sir Ernest Shackleton’s own diary:

Saturday, September 24th, 1921.

At last we are off. The last of the cheering crowded boats have turned, the sirens of shore and sea are still, and in the calm hazy gathering dusk on a glassy sea we move on the long quest. Providence is with us even now. At this time of equinoctial gales not a catspaw of wind is apparent. I turn from the glooming immensity of the sea and, looking at the decks of the Quest, am roused from dreams of what may be in the future to the needs of the moment, for in no way are we shipshape or fitted to ignore even the mildest storm. Deep in the water, decks littered with stores, our very life-boats receptacles for sliced bacon and green vegetables for sea-stock; steel ropes and hempen brothers jostle each other; mysterious gadgets connected with the wireless, on which the Admiralty officials were working up to the sailing hour, are scattered about. But our twenty-one willing hands will soon snug her down.

A more personal and perplexing problem is my cabin—or my temporary cabin, for Gerald Lysaght has mine till we reach Madeira—for hundreds of telegrams of farewell have to be dealt with. Kind thoughts and kind actions, as witness the many parcels, some of dainty food, some of continuous use, which crowd up the bunk. Yet there is no time to answer them now.

We worked late, lashing up and making fast the most vital things on deck. Our wireless was going all the time, receiving messages and sending out answers. Towards midnight a swell from the west made us roll, and the sea lopped in through our washports. About 1 A.M. the glare of the Aquitania’s lights became visible as she sped past a little to the southward of us, going west, and I received farewell messages from Sir James Charles and Spedding. I wish it had been daylight.

At 2 A.M. I turned in. We are crowded. For in addition to McIlroy and Lysaght, I have old McLeod as stoker.

Sunday, September 25th.

Fair easterly wind; our topsail and foresail set. All day cleaning up with all hands. We saw the last of England—the Scilly Isles and Bishop Rock, with big seas breaking on them; and now we head out to the west to avoid the Bay of Biscay. With our deep draught we roll along like an old-time ship, our foresail bellying to the breeze. The Boy Scouts are sick—frankly so, though Marr has been working in the stokehold until he really had to give in. Various messages came through. Today it has been misty and cloudy, little sun. All were tired tonight when watches were set.

Monday, 26th. 47° 53´ N., 9° 00´ W.

A mixture of sunshine and mist, wind and calm. Passed two steamers homeward bound, and one sailing ship was overhauling us in the afternoon, but the breeze fell light, and she dropped astern in the mist that came up from the eastward. Truly it is good to feel we are starting well, and all hands are happy, though the ship is crowded.

Two hands have to help the cook, and the little food hatchway is a blessing, for otherwise it is a long way round. Green is in his element, though our decks are awash amidship. He just dips up the water for washing his vegetables.

With a view to economy he boiled the cabbage in salt water. The result was not successful.

The Quest rolls, and we find her various points and angles, but she grows larger to us each day as we grow more used to her. I asked Green this morning what was for breakfast. “Bacon and eggs,” he replied. “What sort of eggs?” “Scrambled eggs. If I did not scramble them they would have scrambled themselves”—a sidelight on the liveliness of the Quest. Query, our wolf-hound puppy, is fast becoming a regular ship’s dog, but has a habit of getting into my bunk after getting wet.

We are running the lights from the dynamo, and, when the wireless is working, sparks fly up and down the backstays like fireflies. A calm night is ours.

Tuesday, 27th—Wednesday, 28th.

43° 52´ N., 11° 51´ W. 135 miles.

Another fine day. Not much to record. All hands engaged in general work on the ship. In the afternoon the mist arose and the wind dropped. At night the wind headed us a bit, and we took in the topsail. Marr was at the wheel in the first watch, and did well. Mooney, at present, is useless. A gang of the boys were employed turning the coal into the after-bunkers—a black and dusty job; but they were quite happy. We passed a peaceful night. This morning the wind practically dropped. What little there was came out ahead, so we took in all sail. The Quest does not steam very fast, 5½ being our best so far. This rather makes me think, and may lead to alterations in our plans, for we must make our time right for entering the ice at the end of December, and may possibly have to curtail some of our island work or postpone it until we come out of the South. This morning we are in glorious sunshine—the sea sapphire-blue and a cloudless sky; but, alas! noon, in spite of our pushing, gives us only 135 miles. We have allowed a current of 7 miles N. 12° W.

Gerald Lysaght is one of our best workers, and takes long spells at the wheel. Occasionally little land-birds fly on board, and our kittens take an interest in them, as yet unknowing their potential value as food or game (?). How far away already we seem from ordinary life!

I stopped the wireless last night. It is of no importance to us now in a little world of our own.

Wednesday, 28th—Thursday, September 29th, 1921. Lat., 42° 9’ N. Long., 13° 10’ W. Dist., 116’.

A strong wind, with high seas and S.S.W. swell; strong squalls were our portion. The ship is more than lively and makes but little way. She evidently must be treated as a five-knot vessel dependent mainly on fair winds, and all this is giving me much food for thought, for I am tied to time for the ice. I was relieved that she made fairly good weather of it, but I can see that our decks must be absolutely clear when we are in the Roaring Forties. Her foremast also gives me anxiety. She is not well stayed, and I think that the topsail yard is a bit too much. The main thing is that I may have to curtail our island programme in order to get to the Cape in time. Everyone is cheerful, which is a blessing, all singing and enjoying themselves, though pretty well wet; several are a bit sick. The only one who has not bucked up is the Scout Mooney. He seems helpless, but I will give him every chance. I can see also that we must be cut down in crew to the absolutely efficient and only needful for the southern voyage.

Douglas is now stoking and doing well. It will, of course, take time to square things up and for everyone to find themselves; she is so small. It is only by constant thought and care that the leader can lead. There is a delightful sense of freedom from responsibility in all others; and it should be so. These are just random thoughts, but borne in on one as all being so different from the long strain of preparation. It is a blessing that this time I have not the financial worry or strain to add to the care of the active expedition. Lysaght is doing very well, and so is the Scout Marr.

Sir Ernest Shackleton’s diary ends at this point, and there are no other entries till January 1st, 1922.

We now began to settle down to our new conditions of life.

In the deck-house were five small cabins. The Boss and I had the two after ones, but at this time Mr. Lysaght, or the “General” as he was called by all of us (like most nicknames, for no particular reason), occupied one of them, whilst the Boss and I shared the other.

Worsley and Jeffrey had a cabin running the full breadth of the house and the roomiest in the ship, but it had also to act as chart-room. Macklin and Hussey occupied a tiny room of six feet cubed on the starboard side, which contained the medicine cupboard. Here, in spite of restricted space, they dwelt in perfect harmony, due, as they were wont to say, “to both of us being non-smokers.” They were known collectively as “Alphonse and D’Aubrey,” but how the names originated it is impossible to say, for though the versatile Londoner might at times have passed as a Frenchman, the same could not be said for the more phlegmatic Scot.

The corresponding room on the port side housed the meteorological instruments and the gyroscopic compass.

Wilkins and Bee Mason had bunks in the converted forecastle, which contained the photographic dark room, a work bench for the naturalist, and numerous cupboards for the storing of specimens. Wilkins, an old campaigner, had used much foresight and ingenuity in fitting it up, and had utilized the limited space to the utmost advantage. Their cabin was indeed a dim recess and at first proved very stuffy, but before we were many days out Wilkins had designed and fitted an air-shoot, which acted very well and enormously improved the ventilation. Green, the cook, had a cabin beside his galley, which was always warm from the heat of the engine-room—too much so to be comfortable in temperate climes, but he looked forward to the advantage he would derive when we entered the cold regions. All the others lived aft and occupied bunks which were situated round the mess-room and opened directly into it, unscreened except by small green curtains, which could be drawn across when the bunks were unoccupied. It was by no means a pleasant or convenient arrangement, but, with the small size of the ship and general lack of space, the only one possible under the circumstances. The mess-room itself was small, boasting the simplest of furniture: two plain deal tables, four forms, a cupboard for crockery, and a small sideboard. At the foot of the companion-way was a rack of ten long Service rifles. Two of the forms were made like boxes with lids, to act as lockers.

The seating accommodation just admitted all hands to sit together, not counting the cook and the cook’s mate and four men who were always on watch. They sat down to a second sitting. The food was of good quality, plain, and simply cooked. Three meals a day were served: breakfast, lunch, and supper. The Boss presided, and under his cheery example the new hands soon learned to make light of the strange and rather uncomfortable conditions.

Every day for breakfast we had Quaker oats, with brown sugar or syrup (salt for the Scotsmen) and milk, followed by bacon, with eggs (as long as they lasted), afterwards sausage or some equivalent, bread or ship’s biscuit, marmalade, and tea or coffee.

For lunch we usually had a hot soup, followed by cold meat, corned beef, tongue or tinned fish, and bread or biscuit, cheese, jam and tea.

Supper consisted of a hot meat dish, with vegetables, followed by some sort of pudding, bread or biscuit, and tea.

The galley was small, and contained a diminutive range and a number of shelves fitted with battens to prevent things flying off with the roll of the ship. The oven accommodation was small, and admitted of the cooking of one thing only at a time. Here Green reigned over his pots and pans, which, owing to the motion of the ship, proved more often than not to be elusive and refractory.

At meal-times the dishes were passed through a large window port into the messroom by the cook’s mate, and received by the “Peggy” for the day, who served the food and waited at table. Duty as “Peggy” was performed by each man in turn (with the exception of the watch-keeping officers), who also washed the dishes, cleaned the tables, and generally tidied up after each meal. Sir Ernest Shackleton had made it plain to all hands that no work was to be considered too humble for any member of the expedition.

Table-cloths were never used, but the tables were well scrubbed daily, so that they soon took on a fine whiteness. Fiddles were a permanent fitting except when we were in port, for the Quest never permitted us to do without them at sea, whilst in the worst weather even they proved useless to prevent table crockery from being thrown about.

In addition to Query there were on the ship two other pets in the form of small black kittens, one presented to us as a mascot by the Daily Mail, the other, I believe, the gift of a girl to one of the crew. They suffered a little at first from seasickness, but soon developed the most voracious appetites, and showed the greatest persistence in coming about the table for food. They clambered up one’s legs with long sharp claws, “miaowed,” and at every opportunity put their noses into jugs and plates. No amount of rebuffs had any effect upon them, and they had a curious preference for food on the table to that which was placed for them in their own dishes. Two more importunate kittens I have never seen. It is to be feared that one or two of the party slyly encouraged them, for we could never cure them of their bad habits.

The companion steps leading from the scuttle to the messroom were very steep, and at this time Query had not learned the art of going up and down, though he acquired it later. It used to be a common sight to see his handsome head framed in the opening of the window port through which Green passed the food, gazing wistfully at the dainty morsels which were being transferred to other mouths.

These first days with the Boss were very cheery ones, and I like to look back on them. There was little refinement on the ship and more than ordinary discomfort, yet each mealtime was a happy gathering of cheery souls, and conversation crackled with jokes, in the perpetration of which Hussey was by no means the least guilty. The strain of preparation had been a heavy one, and Sir Ernest seemed to be enjoying the quiet, the freedom and the mental peace of our small self-contained little world. I think he liked to find himself surrounded by his own men, and he was always at his best when he had a definite objective to go for.