Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BroadStreet Publishing Group, LLC

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

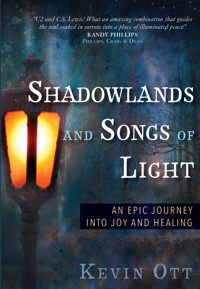

The Bible tells Christians not to grieve as the world grieves and to rejoice in their sufferings. Yet when author Kevin Ott lost his mother unexpectedly in 2010, he sank into a wintry depression. When life seemed the darkest, something surprising happened. While exploring eighteen C. S. Lewis books and thirteen U2 albums, he experienced tremendous "stabs of joy"—the unusual heaven-birthed joy that Lewis wrote about—in the midst of grief. This revelation not only pulled Kevin out of depression, it forever changed the way he experienced the love and joy of Christ. In Shadowlands and Songs of Light, you will: - Learn fascinating details about C. S. Lewis, discover his unique definition of joy, understand how to apply his revelations about joy to suffering, and learn to recognize and cooperate with God's strategic use of joy. - Enjoy a grand tour of U2's discography, with a special emphasis on their exploration of joy and suffering. - Clearly understand, from the perspective of music theory explained in common terms, why the music of U2 is so emotionally powerful and how it serves as a perfect analogy for Lewis's concepts of joy and the Christian ability to rejoice in suffering. - Find inspiration from the personal stories of U2, especially the tragedies that engulfed their youth in Dublin, and see how they worked through that grief and discovered a joy that has kept the band together for over thirty-five years. When the out-of-control nature of the world and your weaknesses throw you off-balance, you can experience God's grandeur and joy— discovering heaven's perspective until it becomes your instinctive, default vantage point every day.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 297

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ENDORSEMENTS

“Grace makes beauty out of ugly things,” Bono sings, and Kevin Ott writes with openness, passion, and hard-won insight about the grace he found in U2 and C. S. Lewis when walking through one of life’s most troubling episodes. Readers will receive the gifts of Ott’s honesty, wisdom, and enthusiasm for life from this book, as I did, and will find that at the intersection of U2, Lewis, and scripture, he has built a richly layered playlist.

—SCOTT CALHOUN, Professor of English, Cedarville University, director of the U2 Conference and editor of Exploring U2: Is This Rock ‘n’ Roll? Essays on the Music, Work, and Influence of U2

U2 and C. S. Lewis! What an amazing combination that guides the soul soaked in sorrow into a place of illuminated peace. Kevin Ott brilliantly takes a deep emotional dive that surfaces in the presence of Jesus. I am so pleased to recommend this book to everyone who has known depression, suffering, and sadness. Kevin artfully combines his skill as a worship leader and inspirational speaker to help us understand the liminal space between brokenness and healing.

—RANDY PHILLIPS, of the musical group Phillips, Craig & Dean

Kevin writes about music in a way I’ve never seen before. It brings all the deeper things of our existence—joy, philosophy, theology, imagination, and hope—to life. It transforms you.

—MOSES SUMNEY, acclaimed recording artist and songwriter, and a collaborator with the Grammy-winning artist Beck

Ott’s insightful analysis and personal testimonial result in a persuasive and powerful presentation of the ability of artistic expression and spiritual exploration to aid in healing and growth. The author’s own training and experience as a musician, composer, songwriter, worship leader, author, blogger, and film critic give him a unique perspective on creativity and the Creator. Readers will discover how it is possible to tap into unexpected depths of joy even while wrestling with profound loss.

—REV. JON EYMANN, MA, Marriage and Family Therapist, Psychotherapist, and Manager of Crisis Services, Santa Barbara County Behavioral Wellness

Kevin’s intense hunger for God comes through on every page. This book does more than just bring joy into times of sorrow. It will change your life and awaken a deeper hunger to pursue God with all of your heart.

—DR. KODJOE SUMNEY, Founder of Mission Africa Incorporated, an award-winning humanitarian group in Africa, and the presiding pastor over the Annual Parliamentary Conference, a national prayer conference held in the parliament of Ghana, Africa

BroadStreet Publishing Group, LLC

Racine, Wisconsin, USA

BroadStreetPublishing.com

SHADOWLANDS AND SONGS OF LIGHT: AN EPIC JOURNEY INTO JOY AND HEALING

Copyright © 2016 Kevin Ott

ISBN-13: 978-1-4245-5291-7 (hardcover)

ISBN-13: 978-1-4245-5292-4 (e-book)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the New King James Version, copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188, USA. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked NIV are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scripture quotations marked NASB are taken from the New American Standard Bible, copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Scripture marked TPT is taken from Song of Songs: Divine Romance, The Passion Translation®, copyright © 2014, 2015. Used by permission of BroadStreet Publishing Group, LLC, Racine, Wisconsin, USA. All rights reserved. www.thepassiontranslation.com.

Stock or custom editions of BroadStreet Publishing titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, ministry, fundraising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected].

Cover design by Chris Garborg, garborgdesign.com

Interior design and typeset by Katherine Lloyd, TheDESKonline.com

Printed in China

16 17 18 19 20 5 4 3 2 1

Dedication

For the daring ones who raised me—Mom and Dad, who established me in Christ’s words, and then used backpacking in the Sierras, imagination, and unconditional love to show me Christ’s heart; my brother Evan, whose contagious love of reading, music, and humor brought constant joy to my childhood; and my brother Ian, who opened C. S. Lewis’ world to me in Oxford and inspired me to believe that anything is possible.

I long for melodies

To chase away the darkness of my fears

And tickle me with laughter

– SALLY OTT

CONTENTS

Part I - Where the Streets Have No Name: The Road to the Secret Place

The Beginning:

ALWAYS WINTER BUT NEVER CHRISTMAS

Chapter 1:

HEAVEN IS ON THE MOVE: STABS OF LONGING

Chapter 2:

HOMESICK FOR THE STREETS WITH NO NAME: DEEP LONGING

Chapter 3:

UNKNOWN CALLER: THE HOUSE OF LONGING

Part II - City of Blinding Lights and Open Windows to Heaven

Chapter 4:

BLINDING LIGHTS AND UNBENDING GRASS: A TRIP TO HEAVEN

Chapter 5:

LIQUID LIGHT AND A WINDOW IN THE SKIES

Chapter 6:

A BEAUTIFUL DAY ON VENUS

Part III - Zooropa: How Our Secular Age Poisons Joy and Grief

Chapter 7:

WINTER IN THE AGE OF ZOOROPA

Chapter 8:

THEY HAVE PULLED DOWN DEEP HEAVEN ON THEIR HEADS

Chapter 9:

ALONG A BEAM OF ULTRAVIOLET LIGHT

Part IV - Every Breaking Wave: When the Flesh Is Weak

Chapter 10:

OVERWHELMED, OUT OF CONTROL, AND A NEW YEAR’S DAY IN THE PEWS

Chapter 11:

THE MOON WOULDN’T LEAVE US ALONE

Chapter 12:

THE DISCIPLINE OF PRAISE AND DAVID’S TABERNACLE: THE MOST TRADITIONAL FORM OF WORSHIP

Part V - There Is No End to Love: Further Up and Further In

Chapter 13:

ASLAN IN THE DARK: REDISCOVERING GOD

Conclusion:

THE DAWN YOU THOUGHT WOULD NEVER COME

Appendix A:

THE COMPLETE STAGES OF JOY PLAYLIST

Appendix B:

A LOOK INTO THE WARDROBE THAT C. S. LEWIS OWNED AND USED FORTHE LION, THE WITCH, AND THE WARDROBE

About the Author

Acknowledgments

Notes

THE BEGINNING

ALWAYS WINTER BUT NEVER CHRISTMAS

The news came while I held the book Planet Narnia in my hands, about to turn the page. My dad was calling from California, three days after Christmas. I was in snowy Ohio, and getting a call from him while I traveled was unusual. Although close, we weren’t phone people, instead preferring face-to-face conversations, usually with a good cup of coffee or a leisurely dinner. There had been several missed calls already and urgent text messages asking me to call back as soon as possible, though I hadn’t heard or seen any of them. I had been away from my phone all morning, and I didn’t think to check my phone as I sat down to read. I was too eager to dive into the world of Narnia. Another call came in. This time I was within earshot of the phone, and I looked and saw all the missed messages. Fear fluttered in my stomach as I lifted the phone to my ear. Something wasn’t right.

By the time the conversation ended, tears slid down my face and fell onto the book.

My mom had passed away during the night.

No one had seen it coming. She had some unusual health problems for a sixty-two-year-old, but nothing that had brought the “d” word to our lips during our Christmas celebration. Only a week earlier she had called me, excited about watching the Christmas movie Elf with me when I returned home.

I had been finishing page twenty-nine of Planet Narnia when the call came in. A few weeks later, I returned to the book to distract myself, but as I turned to page thirty, I couldn’t bear reading it. The page became a point of terrible demarcation, a boundary line as imposing as the Abyss. A few weeks earlier, when I had read page twenty-nine, my mom had been alive. But on page thirty she was gone from the world. A sliver of paper had formed a chasm as significant as BC and AD in history, and it now divided my life.

My mom loved books like Planet Narnia. She would not have approved of me putting it down. But I couldn’t help it. Reading about Narnia had changed from joy to dismal darkness. A shadow had fallen over those lands, enshrouding even the golden face of Aslan the great lion. In the story The Magician’s Nephew, a miraculous fruit from Aslan saved Digory’s ailing mother from death. But instead of a lion bringing a gift to me in the nick of time, a season when it is “always winter but never Christmas”1 came, as if the White Witch had returned and re-established her terrible kingdom.

Moments of bitterness—and envy—struck when I least expected it. The thought of Christians I knew who had received miracles made me angry. Why hadn’t God done a miracle for me?

Many of us struggle with the theological problem of pain, asking the age-old question, “Why, God?” The same question troubled C. S. Lewis, who lost his mother and his wife to cancer. Bono, the lead singer and lyricist of U2, also wrestled with the question; he lost his mother to a brain aneurysm when he was fourteen. It is the struggle of every doubter who asks, “If God is both good and all powerful, why is there suffering?” The Bible has a powerful answer to that question, but the emotional bitterness of the question still aches in the front of our minds like a throbbing headache during difficult times, and especially when we lose someone or something precious to us. And if the sting is severe enough, grief turns into hopelessness.

Of course, the Bible resists such hopelessness, and for good reason. We could spend our lifetimes tracing the stratospheric arc of Christ’s triumph over sin, death, and the Devil, and never come to the end of it.

In fact, for a brief time after my mom’s death, the power of Christ’s triumph roared through my spirit. At her funeral I even sang a song of jubilant praise, rejoicing in her life and in the victory she had found in Christ. I wanted to be strong for my family during that time, and God aided me. Those early days flashed with the light of heaven, a wordless glimpse of what I would later rediscover and place into words.

But as time passed, as the initial shock wore off and the full weight of the loss began to settle in, the light in my heart grew dim and flickered on and off unpredictably, and I wrestled terribly with my mother’s passing. Whenever the stormy days hit, none of the trumpet blasts or shouts of Jesus’ victory broke through the noise. With a tired shake of my head, I would read, “Brothers and sisters, we do not want you to be uninformed about those who sleep in death, so that you do not grieve like the rest of mankind, who have no hope” (1 Thess. 4:13 NIV), and “Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?” (1 Cor. 15:55 NIV).

On the darkest days, such passages would mock me. “Where, O death, is your sting?” the verse would say, and I would bitterly reply, “It’s right here in my chest!”

Questions haunted me. How is a Christian’s grief different experientially from the world’s grief? Yes, we have hope about life after death, but what do we do with it? Is it just an intellectual proposition that we store away with our memory verses? If it is supposed to change the way we grieve, how does that happen? How does it travel from abstract head knowledge to concrete, rib-shaking reality?

A cold, tired flatness settled over me as I sought answers. I tried to write a book that compared Lewis’ The Problem of Pain with the works of Beethoven, but there was no fire in it. Lewis’ words—at times carried along in The Problem of Pain with the diplomatic candor of a doctor explaining a disease—felt dry and lifeless to me, which was unusual. Equally strange, Beethoven’s wondrous music fell flat. I had no real joy in sight.

Then September 9, 2014 came. I did not know it at the time, but that day—which began rather strangely—would change the course of my life. That morning, I was hiking on local beach trails when my brother texted me that U2 had just released their new album, Songs Of Innocence, for free on iTunes. A lifelong U2 fan, I came close to leaping and shouting in celebration right there on the dusty sea cliff trails. It was a windy day, and the coastal environment seemed to rejoice with me. The ice plants and coastal sage scrub shivered with goose bumps as Bono sang about miracles and California sunsets, and the Santa Barbara surf clapped to the music with every breaking wave.

The album awakened something deep within me. I rushed home and poured my thoughts into a review of the album. A few days later, Scott Calhoun, an author and scholar (and a diehard U2 fan like myself), read my review online and contacted me. As we spoke, he mentioned bringing U2 and C. S. Lewis together in a book.

Another light turned on. What if I wrote about my experiences with U2’s music instead of Beethoven’s? (Sorry, Ludwig.) The task of capturing such personal moments, however, felt daunting. God had used piles of U2 albums in my life, but I had never tried to shape those experiences into a book. Such experiences were intensely personal and difficult to articulate, and I had been stuck in exhaustion and mire. The cold flatness wouldn’t leave. I doubted myself.

But as I placed the books of C. S. Lewis and the music of U2 into dialogue—with Christ facilitating between the two parties—God cut through the difficulty and began to address my questions about grief. He threw the gates open, and his answers astonished me.

The ice inside began to melt. Something in U2’s music violently but gloriously cracked open the revelations that Lewis had placed with such care in his books—especially his idea of Joy. Soon my feet were walking along a path again. I was on a journey, and it was transforming me from the inside out.

I should clarify something here: I’m not interested in placing Lewis or U2 on infallible pedestals. I don’t necessarily agree with every word they’ve said from the stage, sung in a studio, or written in a book. But during a period of great inner darkness, the words of Lewis and the musical ideas of U2 became “right Jerusalem blades”2 in the nimble hands of the Holy Spirit. He cut straight through the thick of night.

The answers led me into what I now call the Stages of Joy. These Stages form an adventurer’s map, containing all the things that Lewis and U2 have written about in their work: grand quests, larger-than-life worlds, roaring lions, ancient villains, soaring anthems, songs of heartache, and truth hidden away beneath the garbage and mean streets of this world that Lewis dubbed the “weeping valley.”3

But this book is not just for those who have lost a loved one. Death has many kin, and they come in many forms, not just funerals. When anything precious comes to an unwanted end, whether it’s a relationship, a career, a ministry, or our health, grief speckles us with its shadows.

In this journey, with the help of a large stack of C. S. Lewis books, we will steal down the shadowy slopes and switchback trails together to explore the weeping valley. Along the way, we will unearth many of the most effective (and affecting) musical structures behind U2 songs, and I will provide a U2 playlist that I’ve curated and carefully tied to each chapter. (The playlist will begin in chapter 2, after we’ve explored C. S. Lewis’ unusual concept of Joy in chapter 1.)

Together we will go on a quest for Joy. And when we are done, you’ll be able to listen to each Stage of Joy—a musical meditation to help you remember the points of the book for years to come by simply pushing play.

CHAPTER 1

HEAVEN IS ON THE MOVE: STABS OF LONGING

What a long night on the mountain—one that allowed little sleep. We had pitched our tent on the summit, and the wind beat on us until dawn, whipping the tent’s walls like flags. I was in grade school at the time, and the fierce blowing unnerved me. But my mother, an adventurous woman who had earned the nickname “Mountain Mama” for her love of backpacking, thought the predicament—the wind and freezing darkness surrounding our tent on a mountain—was paradise itself.

As dawn broke, the wind weakened. I emerged from our battered shelter and stepped to the mountain’s edge. A sunrise that seemed as large as the universe opened the morning like a Christmas present, its light glittering across the surface of the rivers and lakes below—silver bows and blue ribbons. I could see miles in every direction, with the mountainous green national parks to the west and the red dust deserts of Nevada to the east.

The sight reminded me of an album cover that bore four musicians standing near a praying cactus tree in a cinematic panorama. I would learn later that the deserts in the distance were not far from where U2 staged the photo shoots for their album The Joshua Tree.1

After a few moments of standing there, I heard a roar above. As I looked up, an F-4 Phantom fighter plane streaked across the sky, flying low over the mountain’s summit. The jet flew at a slow-enough speed that we could see the pilot as it passed by, and he gave us a thumbs-up.

Something pooled in my heart, an expansive longing that surprised me with its intensity. It was not the desire to see another dawn or fighter jet. Those things were pinpricks that spilled an unexpected blood, a yearning that flowed toward something I could not name. The sensation itself—the sudden yearning for something far off and unknown—was more wonderful than a thousand sunrises and fighter jets.

Later in my adulthood, the longing came again during a lightning storm that I witnessed from the window of an airliner. We were flying above the clouds at night and could see flashes of lightning below us. Above the storm the night was clear, as pristine as a summer evening. The Archer constellation—the centaur warrior who bends his bow back to shoot—glittered above the clouds. As his constellation hovered above the lightning, the sensation again welled up, bringing an overwhelming yearning for something far off. I was almost ecstatic. When the yearning ebbed away, I wanted to feel it again; I longed for the longing.

I had experienced the same feeling when I was a child too. My mom was riding a horse in Montana in Paradise Valley, and I was small enough that I could fit on the saddle in front of her. She gave me M&Ms, one at a time, every few seconds, as we trotted through the wilderness. The candy and my mother’s presence brought comfort.

But then another sensation followed. The hugeness of the horse, its head looming before me and towering over my toddler frame, brought the yearning, though it was a quieter kind, filled with the helium of childhood.

I shouldn’t be surprised that this longing baptized me again when I visited Oxford, England, where C. S. Lewis had lived and worked for most of his life. I was a high school student and had gone to visit my brother Ian, who was studying at Oxford University. One night while walking across one of the ancient stone bridges—one that Galileo had likely strode across centuries ago—I looked up and saw the constellation Orion glittering like a cross in the sky. At that moment, my brother saw a homeless man huddled in blankets. He opened his grocery bag, pulled out a bottle of vitamins, and gave it to the man.

What an unexpected one-two punch. I saw the heavens glittering in the sky, and then I saw heaven appearing on earth as my brother showed the love of Christ to a stranger. All of it induced something beyond this world, an inconsolable longing that struck me in the streets where Lewis had walked.

C. S. Lewis would have called these moments of longing “stabs of Joy.”2 In my conversations, so few people have heard about Lewis’ definition of Joy that when they hear me say the word, they think I’m referring to happiness or pleasure. But this special kind of Joy has little to do with circumstantial happiness. In fact, instead of saying “Stabs of Joy,” I find that the term “Stabs of Longing” makes Lewis’ meaning more evident to those not familiar with his writings.

These Stabs of Longing feel close to the intense sensations of homesickness—the pangs that come when we see a place from our childhood or hear an old song that’s tied to our past. Yet it’s not quite nostalgia. It goes beyond that. When this strange Longing stabs us, we feel homesick for a home we’ve never had.

Dr. Timothy Keller, in one of his sermons at Redeemer Presbyterian Church, talked about this Joy, and he wondered if some faint memory of Eden’s paradise—that perfect bliss of fellowship we once enjoyed with God, heart-to-heart and knee-to-knee, sitting with him on top of the world with our feet dangling off the edge—somehow still haunts us.

In his autobiography, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life, Lewis defined this special kind of Joy as “an unsatisfied desire which is itself more desirable than any other satisfaction.”3 For him, the sensations would strike like lightning bolts. They would flash and then disappear: “Before I knew what I desired, the desire itself was gone, the whole glimpse withdrawn, the world turned commonplace again, or only stirred by a longing for the longing that had just ceased.”4

While reading a line from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s Saga of King Olaf, the Longing stabbed Lewis, and he described it this way: “Instantly I was uplifted into huge regions of northern sky, I desired with almost sickening intensity something never to be described (except that it is cold, spacious, severe, pale, and remote) and then, as in other examples, found myself at the very same moment already falling out of that desire and wishing I were back in it.”5

Those few seconds of Longing, at least the ones that Lewis recorded, probably added up to less than a minute on the clock, yet they changed him forever, as he noted: “the reader who finds these three episodes of no interest need read this book no further, for in a sense the central story of my life is about nothing else.”6

After I lost my mom, I was shocked to discover—especially during the first few weeks after her funeral—these same Stabs of Longing, though in a slightly different form, hiding in the shadows of grief. These pangs shuddered through my spirit with surprising strength and lingered longer than the usual flashes of Joy. I began to question the whole nature of grief. I felt like a man who sits in darkness thinking he is in a prison cell behind locked doors, but when the lights come on he discovers he’s free. There is no prison. In fact, he’s been sitting in a palace all along.

That’s almost how Lewis describes his experience with grief when, at one point in his mourning, the sudden weight of heaven’s reality invaded:

One moment last night can be described in similes; otherwise it won’t go into language at all. Imagine a man in total darkness. He thinks he is in a cellar or dungeon. Then there comes a sound. He thinks it might be a sound from far off-waves or wind-blown trees or cattle half a mile away. And if so, it proves he’s not in a cellar, but free, in the open air. Or it may be a much smaller sound close at hand—a chuckle of laughter. And if so, there is a friend just beside him in the dark. Either way, a good, good sound. I’m not mad enough to take such an experience as evidence for anything. It is simply the leaping into imaginative activity of an idea which I would always have theoretically admitted—the idea that I, or any mortal at any time, may be utterly mistaken as to the situation he is really in.7

The pain of losing such a precious treasure removed a veil from my eyes. The facade of this world’s so-called ultimate reality became more evident. The skin of the universe was growing thinner and the walls of heaven were growing thicker.

What was really strange, however, was that this presence of Joy did not weaken the strength of grief. In fact, even as Joy came, a house of sorrow was rising over my head.

The House of Grief

In Surprised by Joy, C. S. Lewis had the luxury of looking back on his Stabs of Longing like a man watching a train from a platform. The roaring blur of the train excites the man’s senses briefly, but then it vanishes and he has all the time he needs to reflect on the train’s passing as he stands on the quiet, unmoving platform.

Likewise, in The Problem of Pain, Lewis observed human suffering and untied its theological knots from the safe distance of paper, ink, and contemplation.

But when grief hit him the hardest—after he lost his wife to cancer—he recorded sorrow not as a man standing on the platform making quiet observations but as a man snatched up against his will onto the train, trying desperately to keep his hat on. Nothing remained still. His inner world lurched and rattled, and he scribbled his raw, wild observations about grief when the pain was still white-hot. These real-time field reports became the book A Grief Observed.

In A Grief Observed, the reader gets a sense of unexpected enormity, as if Lewis had stumbled into a giant labyrinth that he had underestimated; and, like any wise explorer who encounters an imposing structure, he looks at it with something akin to fear. The first sentences of A Grief Observed capture the moment perfectly: “No one ever told me that grief feels so like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering of stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.”8

A Grief Observed also feels labor-intensive, exhausted, as if Lewis is dragging himself up the side of the mountain as he writes—a sharp contrast to his previous books. In Surprised by Joy, the tone is lighter. Every word springs with energy and moves forward with delight, as if he were strolling through his favorite hills outside Belfast.

In a similar way, Joy—that sharp, wonderful Stab of Longing—has a lithe, muscular lightness to it. It’s deft. It produces longing that weighs heavy on the heart, but it does so with precision and coordination—a mix of strength and poise, like the steel toes of a ballerina. There’s a glorious drama in it, and Joy strikes with all of it at once. It dashes in with the agility of a hummingbird claiming its nectar from the flower, and then zips away. It pricks, then vanishes, leaving a wake of mystery and longing behind it.

But grief couldn’t be more different. It comes, and then it never leaves. It’s clumsy and uncoordinated. There’s nothing virtuosic about it. It has all the delightful precision of a concussion grenade.

After the initial shock, and after it diffuses over months and years, grief can take a different form. A nurturing melancholy can fill it at times. It hovers and broods over us, like the bright star going about its unwavering, methodical “priestlike task,” as the poet Keats wrote.9 A priest serves others, washes their feet, and removes debris from the spiritual road. Grief, at times, washes our feet too, and it clears a path for Joy. That path, however, also carries with it an unavoidable solitude.

The moment when grief encloses you like a cocoon, you leave this present world. In a sense, you enter a private universe, even as you go about your daily errands. No matter how many bereavement cards or casseroles arrive at your door, no matter how many times someone sits down with you and shares your tears with a reassuring arm around your shoulder, eventually that person will have to leave and return to the affairs of his or her life. No one can enter that place of grief inside your soul and reside there, tasting it day and night, as you must do. The whole experience becomes a quarantine room—a large, empty house that only you can enter. And like a solidly built fortress, it is not going anywhere.

Racing Through a Mansion of Many Rooms, a Nest of Gardens

But the House of Grief is not a one-room apartment where you sit staring at a wall, never to move again. It’s not that kind of private universe. It’s not a closet. Not a static experience. Once you step inside, you’re in perpetual motion. An unseen hand pulls you down new halls, into unfamiliar rooms, a sudden right turn into a courtyard you’ve never seen before and then a quick left into a ballroom that you didn’t know even existed in the house. Something, or Someone, is pulling you further into a many-walled nest of gardens within gardens—a mansion with many rooms that lead to a mysterious location deep within.

In other words, grief has linear motion. Progress. A forward leaning. A pilgrim’s steady walk. Lewis described it this way:

Grief is like a long valley, a winding valley where any bend may reveal a totally new landscape…. Sometimes the surprise is an opposite one; you are presented with exactly the same sort of country you thought you had left behind miles ago. That is when you wonder whether the valley isn’t a circular trench. But it isn’t. There are partial recurrences, but the sequence doesn’t repeat.10

Grief’s strange, slightly familiar but different terrain can feel horrifying at times—more like a scary house of mirrors than a mansion. But even when terror and confusion abound, there is still motion. There is direction, and a purpose behind the motion. Lewis makes a profound discovery: grief is not cyclical. It’s not like the clinical routine of an annual medical exam. It’s a long journey along a linear path that never sees the same landscape twice.

It’s a quest story.

You’re a traveler in a strange land, you feel a drive toward a destination (though you don’t know its name yet), and every turn of the road brings you to a blank edge of the map. Joy and its Stabs of Longing have this quest-like motion too. Joy drove Lewis to search for truth, and the insatiable pursuit culminated in his faith. In his own words regarding that Longing, “the central story of my life is about nothing else.”11

Now we have common ground: Joy and grief both produce intense linear motion toward a destination, though we do not yet know the destination.

And it is this shared motion that begins the Stages of Joy.

Scripture

“Rise, let us be going” (Matt. 26:46).

Notes for the Quest

In C. S. Lewis’ journey to Christ, the intense longing of Joy caused him to rise and go and hunger and thirst for something greater—something far off on the horizon. The longing stirred him to move. Grief and Joy produce a special kind of motion. And in God’s hands, that motion can lead us on a life-changing journey—but only if we’re willing to rise from where we lie. Sometimes Jesus’ commands are short and simple: “Rise, let us be going.” We would do well to obey and take action, even if that action is as simple as getting up from where we lie and moving forward, allowing the linear motion of longing, whether that longing comes from Joy or grief, to draw us down the road on a new journey.

A Prayer for the Journey

Abba Father, stir my heart to rise from complacency or spiritual paralysis—anything that might keep me from setting out on this new road. Help me to recognize and remember the Stabs of Joy that you’ve allowed to pierce my life over the years, and help me to recognize Joy when it bids me to “rise, let us be going” during times of great sorrow. In Jesus’ name, amen.

More Bible Verses for the Road

Psalm 63

CHAPTER 2

HOMESICK FOR THE STREETS WITH NO NAME: DEEP LONGING

Let us spend what is left in seeking the unpeopled world behind the sunrise.

– C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: The Chronicles of Narnia

Song to cue: “Where The Streets Have No Name”

from the album The Joshua Tree

Inconsolable motion.

If I were to sum up the band U2—every song, every album, and every tour of their almost-forty-year career—those two words would be sufficient.

Inconsolable motion.

It’s the motion of something that refuses—obstinately, passionately, religiously—to be comforted or lulled into slowing or stopping. It refuses to settle, and fears self-contentment. It’s always straining to see what’s beyond the horizon. Its eyes are “impregnated with distance.”1

Other words such as restless or driven might apply to U2, but they’re not strong enough. The word inconsolable expresses the idea of grief at full strength, the most intense state of sorrow in the human experience.2 The stakes of this word are matters of life and death—the highest stakes.

U2 has always been about the highest stakes: analyzing them, grappling with them, swallowing the emotions that flow from them, and regurgitating their efforts into recorded sound. As Billboard once observed: “The foursome had always been earnest and strident—willing to spout off on huge issues like God, death, and war.”3

Their gutsy, stubborn, almost insane career moves provide plenty of examples of this, whether it was reinventing themselves in 1991 with the revolutionary, experimental masterpiece that no one saw coming—Achtung Baby