Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

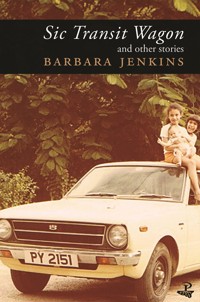

The stories in Sic Transit Wagon bring together a rich, evocative and authentic tapestry of Trinidad life, from the 1940s to the present day. We move from the all-seeing naivety of a child narrator trying to make sense of the adult world, through the consciousness of the child-become-mother, to the mature perceptions of the older woman taking stock on all that has gone before. In the title story – a playful pun on the Latin phrase on the glory of worldly things coming to an end – the need to part with a beloved station wagon becomes a moving and humorous image for other kinds of loss. Barbara Jenkins was born in Trinidad. She studied at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth, and at the University College, Cardiff. She married a fellow student, and they continued to live in Wales through the whole decade of the 1960s, before returning to Trinidad. Her stories have won the Commonwealth Short Story Prize (Caribbean Region) in 2010 and 2011, for 'Something for Nothing' and 'Head Not Made for Hat Alone' respectively; the Wasafiri New Writing Prize; the Canute Brodhurst Prize for short fiction from the Caribbean Writer; the Small Axe short story competition, 2011; and the Romance Category, My African Diaspora Short Story Contest.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

These stories first appeared in the following publications: “It’s Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White”, Wasafiri Vol. 26, No 1. Issue no. 65 Spring 2011; “Ghost Story”, Small Axe, No. 38, Vol. 16/2, 2012, Duke University Press; “It’s not where you go it’s how you get there”, in Moving Right Along, Lexicon, Trinidad, 2010; “Gold Bracelets”, The Caribbean Writer, Volume 24, 2010; and “The Talisman”, The Caribbean Writer, Volume 26, 2012.

BARBARA JENKINS

SIC TRANSIT WAGON

AND OTHER STORIES

First published in Great Britain in 2013

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2013 Barbara Jenkins

ISBN 13 (PBK): 9781845232146

ISBN 13 (Epub): 9781845233235

ISBN 13 (Mobi): 9781845233242

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form

without permission

For my mother, Yvonne Lafond,and my husband, Paul JenkinsBetter late than never

CONTENTS

1.

Curtains

It’s Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White

Maybe Tomorrow Will Be Better

The Day the Earth Stood Still

I Never Heard Pappy Play the Hawaiian Guitar

Gold Bracelets

2.

Monty and Marilyn

The Talisman

It’s Not Where You Go, It’s How You Get There

Across the Gulf

Ghost Story

3.

Erasures

To-may-to / To-mah-to

Making Pastelles in Dickensland

A Perfect Stranger

Sic Transit Wagon

1

CURTAINS

That day the breeze was blowing more strongly than usual, or perhaps it was blowing at its usual strength, but I had no reason to notice it before. The long, white curtains that hung from the top of the doorframes had shaken themselves loose of the ribbons that restrained them and were swelling with breeze in and out, lifting over and flapping with soft slaps against the chairs and tables in the gallery, filling the spaces of the wide-open doorways – doorways so wide, so high, that Uncle would have me, just three years old, sitting astride his shoulders, clinging hard to the reins of his hair, while he galloped me, wildly shrieking with fear and excitement, from bedroom to gallery to another bedroom to gallery to living room to kitchen. In and out the dusty bluebells, he would sing, dancing me from one room to the next, through the encircling gallery of my grandmother’s home that was my home too, with my mother and her brothers.

The curtain, full of wind, billowed over my bed that day, brushing a feathery tickle across my face, waking me earlier than usual. I opened my eyes and looked around for my mother but she was not in our bedroom. I did not call for her because, when I listened to the world I had just woken up to, I could hear her voice and my grandmother’s voice coming from the gallery, just outside our bedroom. There was something slow and serious about the voices, one after the other, which made my own voice stay quiet while pulling me towards theirs. I slid down off the big bed and stood behind one of the curtains. That hard, strong breeze bellied the curtain. It wrapped itself round me, hiding me in its long folds as I stood in the doorway, watching and listening. The thin, pale day drew only faint broken lines of light through the waving branches and leaves of the big chenette tree outside, but I could see the back of my grandmother’s dress with its printed yellow flowers on leafy green vines peeping through the woven cane of her rocking chair, her long grey plait swinging from side to side over the back of the chair as she rocked back and forth, back and forth. The rockers went squeak, bump, squeak, bump, against the hard mahogany floor with a rhythm so regular that, even if I closed my eyes, I could tell when the next squeak, the next bump, was coming. My mother was standing in front of the rocking chair, facing my grandmother and facing me too, but she couldn’t see me where I was hiding. She was wearing her white housedress with pink and blue flowers sprinkled all over it and big pockets and a big round collar edged with white lace.

Through the blurriness of the curtain, I could see her head bent down and I could see her arms only down to her elbows. I imagined her holding her hands together behind her back, her fingers twisting round and round the ring she wore on her right hand, the ring with the blue stone she said was her birthstone. She always did that ring twisting when her hands were behind her back. I wanted to go out to the gallery, to stand near my mother, but there was something strange about the way they held their bodies, apart and stiff, the way they spoke to each other, as if they were not the same mother, the same grandmother that I had left when I fell asleep the night before, and it held me back, made me silent and secretive. My grandmother was speaking. She spoke for a long time. Her voice was not loud but it came out solid and hard like a plank of wood – a plank of wood with knotholes and rough patches. I understood only some of what she said… not again… shame… make your own bed and lie in it.

I wondered why she was talking so seriously about making a bed. I knew my mother hadn’t made our bed yet – I had been asleep there until a little while before. Why should that make my grandmother so vexed as to quarrel with my mother? My mother spoke softly and only for a little time, not interrupting but taking her turn. I could hear none of her words. Her voice did not have its usual up and down curves. It was just flat and soft and down. She was not looking at my grandmother – she was looking down at her feet and that made her words fall to the floor. Was not making your bed and lying on it such a naughty thing to do? I felt a strong urge to go out to the gallery and stand with my mother and hold on to the tail of her housedress to show that I too was sorry about the not making of the bed, but, at the same time, I sensed that the talking was somehow about important big people business and I should not interrupt. I was afraid that if I went out there to them they would be angry with me and I would be scolded and sent off to Cooksy in the kitchen.

When I got tired of standing I sat on the floor, near to one of the giant hooks in the wall that held open the big glass-paned doors. I ran my hand along the cold, hard hook. I pushed my fingers alongside the head of the hook, into the round metal circle screwed into the door. I wanted to pull out the head of the hook and free the door. My grandmother, uncles and mother had all warned me, from the time I could crawl about, that I was not to unhook the doors or they would slam shut in the breeze, breaking the glass, sending splinters flying everywhere, especially into my eyes and I would go blind. I used to walk about the gallery with my eyes shut, stumbling into furniture, practising how I would get around if one day I disobeyed, the glass shattered and I went blind. I wanted to unhook the door, so that the door would slam shut, and then they would stop the talking, because I didn’t like how I felt when I heard my mother’s voice, so soft and having no tune in it. But I did not lift the hook out of the metal circle, even though I wanted to. Instead I stood up and paid attention to the talking again which had got so soft I couldn’t make out any words at all.

My mother looked up at my grandmother and said something that must have been a question because her voice rose up at the end. The rocking chair stopped. The soles of my grandmother’s slippers made a slap on the floor as she leaned forward and put her feet down. She shook her head from side to side. My mother looked down at her own feet again. She slowly turned away and walked towards our bedroom, but she didn’t see me because I was still wrapped in the curtain and standing very still and quiet. I saw her look at the bed, at where I usually slept. Maybe she was looking for me. Then she went and sat at the foot of the bed. She sat with her chin resting on her hand, her elbow propped on her knee. She looked down at her lap, glanced back at the bed, then turned around again. Maybe she thought I was at breakfast in the kitchen with Cooksy. Her back to me, she looked straight ahead, right into the mirror of the dressing table that she was facing. She could not have been really looking into the mirror or she would’ve seen me, the lumpy ghost in the curtain I saw reflected in the mirror’s wide silver face.

She stared and stared ahead and then she dropped her face into her hands. I could see her shoulders shaking and I could hear her going… huhhh… huhhhhn… huhhh… huhnnn, as if she was squeezing her voice inside, trying to hold it back, but some of it pushed its way out anyway. I felt an ache in my chest. I didn’t understand what was going on. I wanted to hug her and make it all right, but I didn’t know how to let her know that I was hiding in the curtain for she would realise I had been looking on and listening all along, and I thought she wouldn’t like that, so I just stayed quiet where I was.

After a long while, she leaned forward, pulled open a drawer, took out a handkerchief and blew her nose in it. She looked again into the drawer and started taking things out of it and throwing them over her shoulders on to the bed. In a great hurry, she pulled open all the drawers, one by one, and did the same thing, flinging everything on our bed behind her, not seeming to care where they landed. Sheer stockings and the grey elastic rings that held them up, her panties and brassieres and girdle, her yellow nightie and the white one, her flesh-coloured silky petticoats and half-slips flew out, undoing their soft, careful folds and piling up in an untidy heap. My clothes came out too – white vests and panties and socks, flowery seersucker pyjamas. When she was done with the drawers, she pushed them shut and sat a while doing nothing. Then, she stood and walked slowly to the wardrobe and, from it she lifted out clothes on hangers, looking at each item – the blue silk dress with smocking at the front that I loved to look at, trying to work out how the stitching was done; the green taffeta one that made wavy patterns of light and shade running up and down it when she walked in it, that made me think of dragonflies tipping their heads to ripple the mossy pond at the Botanic Gardens; her slippery blouse with long see-through sleeves, and the floppy polka-dot one with a floppy bow at the front; a grey pleated skirt and a stiff narrow black one with slits on the sides. Then she lifted out my dresses – the plaid dress with the wide red sash for going for walks, and the yellow organdie one for church. All of these she touched – a collar of one, a lacy edge of another, a sash, a bow, then placed them with slow care on the bed.

She looked at the bed, her eyes moving over the heaps and the piles of things there, and turning away abruptly, she walked through the door that connected our room to Uncle’s bedroom. I could hear her talking with Uncle and a little while after she came back with a big brown grip that she put on the bed. When she lifted some little gold catches, the grip popped open in two halves. One by one she folded all the clothes that were on the bed, put them into the grip, went out the room again and came back with a paper bag that had handles; she put that on the bed too. From her dressing-table top, she took her hairbrush and comb, the round box with pink face powder and the square one with white body powder and its fluffy puff that made you sneeze, and put them in the paper bag. The little tortoiseshell box with her jewellery went into her white handbag, which she then snapped shut. I hadn’t noticed when she put the handbag on the bed. She opened the handbag again and took out a small-change purse. She twisted open the top and looked inside, took a roll of paper money from the brassiere she was wearing and put it in the change purse, clicked it shut and put it in the handbag, closing that too. Then she opened it again and took out a tube of lipstick. She twisted the tube and ran the red tip of lipstick over her mouth without looking in the mirror as she usually did. She put back the lipstick and shut the handbag once more.

Digging into the brown paper bag, she pulled out the comb and dragged it through her hair. It met a tangle and she tugged at it until the tangle came out along with a few long strands which she pulled off the comb, rolled into a ball and dropped on the dressing table. She opened the handbag again, took out the tortoiseshell box, opened it and picked out a pair of gold earrings, the ones that hang down with an oval coin with a flat statue of a lady in a long dress and veil on it. I looked to see if she would take out and wear the gold bracelets that she always kept in that box, but she did not.

She put back the tortoiseshell box and closed the handbag, opened the wardrobe and pulled out a pair of white shoes – the ones with peep holes at the front where you could see her big toes. Next, she opened the grip and took out a pair of stockings and the elastic circles and closed the grip. She put on the stockings and the elastics, stood up, bent her head round to look at the back of her legs and put on the shoes. She opened the grip and put the slippers she had been wearing into the grip and closed it again. When she looked down at her housedress, she stopped for a bit, then she began to pull it off in a hurry, lifting it over her head. She opened the grip and took out the stiff narrow skirt and pulled it on. The zip wouldn’t go right up and she left it like that, halfway done, while she scrambled around in the grip and took out the girdle, stepped into in, wiggling and wiggling until she pulled it right up under the skirt. Then she bent her head, looked at the waist of the skirt and finished pulling up the zip. I could see the floppy polka-dot blouse with the floppy bow right on top the things in the grip. She just threw that blouse on. The floppy bow was not even; one tail hung lower than the other, but she didn’t seem to notice. She did not look at herself in the mirror, not even once.

My mother picked up the handbag and walked out the door, right past where I was hidden in the curtain, across the gallery. I could hear the heels of her shoes going toc, toc, toc down the long flight of concrete steps, the sound getting fainter and fainter until there was no more sound. I stayed shrouded in the caul of that curtain for a long, long time, looking through it at the brown grip and the paper bag and the thrown-off housedress curled up on the bed. I stayed there waiting, listening for the toc, toc, toc to come back.

IT’S CHERRY PINK AND APPLE BLOSSOM WHITE

When I was eleven, my family split up. I didn’t know then and I don’t know now what caused this to happen. All I know is that one day my mother said that we were going to stay with some other people. It was right after I had taken the Exhibition exam for a high school place; the school holiday was about to begin and I remember my confusion as we children always spent the six weeks of holidays with our grandmother, at my mother’s childhood home in Belmont Valley.

Maybe our father had decided he wouldn’t continue to pay rent for our three rooms in the house in Boissiere Village. He didn’t live with us, he visited in erratic pouncings. When his car slid silently to a halt at the house, the message, Yuh fadda reach, ran through the neighbourhood and, wherever we were, we scampered home. He sat on the bed, pointing to his left cheek for us to kiss and I wished for sudden death rather than enter his aura of smoke, staleness and rum. My mother made him coffee. One of us carried it to him. He drank it and left. Without his support, perhaps my mother saw the scattering of her brood as her only option when she no longer had a home in which we could all live together.

When she told me we would be going somewhere else, I got a cold, hard clenching feeling in my belly, but I didn’t have the words to tell her that. As she was leaving, she stood facing me, held my shoulders and said, “Be a good girl,” as she did whenever she left me anywhere, but that time my mother didn’t look into my eyes; she looked down at the floor. I saw her cheeks were smeared and wet; I was puzzled. I touched her face; the powder she rarely wore came off on my palm. She was dressed as if for a special occasion, a christening or a funeral, and, as she turned away, I caught hold of the skirt of her smoke-grey shantung dress with the tiny pearl buttons like a row of boiled fishes’ eyes. My hand left a dull orange smear of Max Factor Suntan. I saw the stain I had made and I felt glad.

None of us was left with family. I was to go to a neighbour; one sister was sent to San Fernando to stay with friends of my mother’s – people we children didn’t know; where the other went I don’t remember, but I do know that our mother took only my one-year-old brother with her, and we didn’t know where. I think that she must have been planning this for a while; the far-flung arrangements would have been difficult to negotiate quickly without telephone, and the timing was too convenient to be coincidence.

My new home was a shop. Over the street door was a sign, white lettering on black, “Marie Tai Shue, licensed to sell spirituous liquors”. I knew the shop well, since, as the eldest, I was the one sent to make message. We children on the making message mission scrambled up with dusty bare feet to sit on the huge hundredweight crocus bags of dry goods stacked against the interior walls of the shop until Auntie Marie called out, “What you come for?” Nobody but the bees cared that we were sitting on foodstuffs – rice, sugar, dried beans, and the bees only bothered if you sat on a sugar bag without noticing their plump golden-brown stripes camouflaged against the brown string of the sacks, heads burrowed into the tight weave.

Early morning, my mother sent me for four hops bread and two ounces of cheese or salami; mid-morning, half-pound rice, quarter-pound dried beans, quarter-pound pig tail, salt beef or salt fish; more hops bread and two ounces of fresh butter mid-afternoon. I had no money for my shopping; we took goods “on trust” all week. The items were handed over, the amount owed was noted in Chinese script on a small square of brown paper selected from a creased and curling pack threaded through a long hooked wire suspended from a nail driven into the back wall. I would peer over the counter to watch Auntie go to the dark recesses of the shop, hear the thunk of the chopper as it cleaved through the salted meat into the chopping block, then remember to call, “Mammie say cut from the middle,” or “Mammie say not too much bone.” On Saturdays, my mother went herself for the week’s supplies: Nestlé’s condensed milk, Fry’s cocoa powder, bars of yellow Sunlight soap for washing clothes and a single-cup sachet of Nestle instant coffee, just in case. She’d bring a rum bottle for cooking oil and a can for pitch-oil for the stove. What she was able to take away depended on Auntie’s goodwill and on how much of that week’s accumulated “on trust” total she could wipe off.

In my new life I was on the other side of the shop counter with a new family. The six children ranged in age from fifteen to nine. I moved in with a cardboard box and a folding canvas camp-bed which the boys set up in the girls’ room, between Suelin’s bed and Meilin’s and Kanlin’s double-decker. One of the boys hammered two new nails behind the bedroom door where my clothes would hang alongside the girls’: a Sunday dress, two outgrown school overalls as day clothes and another for the night. That first night, I closed my eyes and saw pictures running behind my eyelids. I saw my cousins at my grandmother’s climbing trees, picking and eating chenette, mango, pommerac, playing in the rain and the river. Without me. I saw Miriam, chief rival as my grandmother’s favourite, brushing Granny’s long silver hair until she fell asleep at siesta-time. Perhaps, with me not there, Uncle Francois was choosing Jeannie to help him pack the panniers of gladioli and dahlias to take to the flower shop. I felt red heat rise and fill my head at my mother for cheating me of what was mine by right. Then I remembered her face when she was leaving me. I wondered why she wouldn’t look at me. Did she feel bad about leaving me where I didn’t want to be? I felt a tugging tightness in my throat about being glad for spoiling her best dress. I had looked at her downcast face and promised I would be a good girl and not give Auntie Marie any trouble.

Life in my new home seemed one of plenty – the whole grocery to choose from, a shower with a door and latch, toothpaste not salt, their own latrine. I felt lucky. All these luxuries were mine too. On dry days, Meilin and I scrubbed clothes in a tub and spread soapy garments on a bed of rocks in the backyard to bleach in the sunshine. Next day, two of the boys rinsed and wrung out the clothes, draping them over hibiscus and sweet lime bushes to dry. Between us we swept and mopped the floors of the two bedrooms and the common living and dining space at the back of the shop where Auntie slept at night in a hammock of bleached flourbags. After closing the shop at night, Auntie cooked dinner, my first experience of strange food: grainy rice or noodles infused with the salt and fat of chunks of Chinese sausage, patchoi, cabbage, carrots fragrant with thin slices of ginger steamed in a bamboo basket above the simmering pot, meat slivers flashed in a wok. Auntie spoke Cantonese to her children; they answered in English. I listened to tone, looked from face to face, followed the thread and joined in.

The bigger children helped in the shop; I wasn’t expected to, but I often sat on a bench, watching and listening and learning. I could fold brown paper so that the edges were straight and, inserting a long, sharp knife, cut to size for half-pound, quarter-pound, two-ounce dry goods and farthing salt, but two tricks of the trade defeated me. The first was twisting a sheet of paper up at two sides around dry goods to make a firm, leak-proof package and flipping the whole over to close the top in a fold. The second was unpicking the ends of the stitching across the top of a crocus bag so that, when you held the two loose ends of string and pulled, the top of the bag fell open to expose sugar or rice, like Moses unzipping the Red Sea to reveal the dry land below, leaving you with a long zigzag piece of twine, perfect for flying kites.

I had long idle spells when I would read – anything, everything. On the narrow shelves along the shop’s back wall were goods we seldom had at home. I would pick up these luxuries, hold them, read the labels: Carnation evaporated milk, Libby’s corned beef, blue and gold tins of fresh butter, Andrex toilet paper, Moddess sanitary napkins. My hands caressed things from England, Australia, New Zealand, USA and I felt a current connecting me with those places. The boys had comic books that they hid under their beds. I would borrow a comic and steal away to read it quickly and borrow another. Comics pulled me immediately into their unambiguous graphic world where I had the power to do anything. I could save the world from alien invasion, rescue beleaguered innocents from danger, fight forces bent on destroying civilisation. With just Kryptonite, a Batmobile, a two-way wrist radio, Hi-Ho Silver, I leapt over skyscrapers with a single bound, stopped speeding trains with bare hands, deflected bullets to ricochet onto the bad guys, big things, real things. When I stopped reading, I looked at my world, hoping to find some disaster I could avert, but I saw no Martians, missiles or maverick trains, so I opened another comic, and another. I lived in so many other worlds that, for much of the time, I moved through my real world as if it was just something else I was reading and had got lost in. Each new thing I read added to my world, making my own life something I had to let happen, like a story whose pages I was turning, not something I could shape myself.

For the people I lived with, reading brought them the world they had physically left but had carried with them in everything they thought and did. The Chinese community had an informal circulating library of magazine-type papers from China, “Free” China. Auntie and Suelin would read the Chinese script from the back page bottom right corner and work their way up the columns to the front page. From the synopsis in English, I learnt about Sun-Yat-Sen, saw pictures of Chiang-Kai-Shek with the glamorous cheongsam-clad Madam Chiang-Kai-Shek, and read about Mao-Tse-Tung. The first two were revered, the last hated – he and the Communists had driven them out of China, stealing all they had and then seizing their family. I wondered whether the Communists had captured my mother, forcing her to give us away and if this was so, how did she know that the people she left me with could be trusted not to give me to the Communists in exchange for their own captured family? I didn’t think they would do this because they were taking care of me, just as if I was one of the children of their family. But then, maybe they were fattening me up like the witch in Hansel and Gretel, because sometimes they had big gatherings and feasts.

When fellow shopkeepers, laundry owners and restaurant proprietors came to visit on Sunday, the white-shirted men and their jade-bedecked wives would sit round a table quickly assembled from an old door and packing cases, covered with a white sheet. Competing chatter in passionate, high-pitched Cantonese – sounds like frantic trapped birds crashing into glass panes – would rise to a clamour, and just when I thought a fight would start, there would be explosions of laughter, the brandishing of magazines, and the pointing at one another with raised chopsticks, still pinching slick black mushrooms and floppy white wantons. There was a constant flow of china bowls and platters bearing translucent rice noodles and bright green chopped chives floating in clear broth, shrimp and pork fried rice, meat, soybean curd, bamboo shoots, water chestnuts, glistening roasted duck, rice wine poured from a ceramic bottle into matching thimble cups, sweet and sour prunes hidden in layers of paper, preserved ginger. I had never been to a restaurant, had never imagined such plenty of food and noise. I had never before seen this close-knittedness, this exclusiveness of clan bonding. I stayed on the edge, watching. I felt I was both in and at a movie.

On a normal weekday I found other entertainment, watching bar customers. Men came in from mid-morning, ordered shots of rum and single cigarettes, sat on long benches at the wooden table to drink, smoke, play cards for small stakes, talk, argue. On payday they would buy nips and flasks, pour on the dusty concrete floor an offering to those gone before, and lime as long as they could until their women sent children to rescue the residue of the family funds before it was all smoked, drunk and gambled away. We in-house children served the orders, cleared up glasses and ran our own riotous card games in a corner with burnt matches as our stakes.

But best of all was the radio in the bar, a novelty for me. It was kept permanently tuned to WVDI, beamed from the American base at Chaguaramas. The call signal, “This is station WVDI, the armed forces radio station in Trinidad”, was said in that cool, confident, leisurely, Yankee drawl that conjured up other lives entitled to Wrigley’s Spearmint chewing gum, soda fountains, high school sweaters emblazoned with huge single letters, driving on the right side of the road in a convertible, hair blowing in the wind. That year, Perez Prado and his Cuban Orchestra dominated the airwaves with his number one hit, “It’s Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White”. Twenty times a day or more, a trumpet wailed the opening bars, that long sustained waaaaaaah, a puppet string of sound, pulling me to my feet, making me forget who, what, where, lifting me into that upswelling blare. I was Scarlett O’Hara, smooth thick black hair curling round shoulders, long slender fingers curved into back of the neck of someone like Rhett Butler, his smouldering eyes scorching mine; my True Romance magazine figure was draped in a V-necked cowl with a flared skirt which swirled and lifted as we two, entranced, mamboed across the dance floor lost to the admiration and applause of all.

When the song was over, Meilin and I, panting with exertion, would collapse on a bench and she would tell me about her school. She had been in high school since last year, when a neighbour brought the newspaper to Auntie Marie to show her that Meilin’s name was there, that she had passed the Exhibition exam. Auntie Marie couldn’t read English, and she called Meilin to read her own name, to make sure. I wondered if my name would be on the list when the results came out. I wondered how I would know, how my mother would know, as we didn’t buy papers. As we talked about Meilin’s school, I wasn’t sure I liked the sound of it – Bishop’s. Their uniform had a funny hat with pointy corners that made them look like the soldiers in history books about Napoleon. St Joseph’s Convent girls wore floating white veils and looked like they were little nuns already on their way to heaven. Also, Bishop’s girls had gym twice a week and afterwards showered together. This bothered me.

“Does that mean people could see your punky and totots?”

“After a while, people don’t bother to look. You get accustomed.”

I’d have to do very well in the exam to win a free place at either school – if I only passed, my mother couldn’t pay fees like Meilin’s. We made a pact. If I won first place, I told her, I would choose her school. We hooked the little fingers of our right hands to seal this pledge. At times like those, Meilin shared with me her burgeoning knowledge of life. She told me about her monthly bleeding and I said it wouldn’t happen to me. She told me what men and women did in secret and I didn’t believe her. She told me that babies came out through their mothers’ punkies and I knew then that she was just making it all up. We danced through that long holiday, we and Perez Prado singing, “It’s cherry pink and apple blossom white, when your true lover comes your way”. It was about flowers we had never seen, emotions we were too young to understand.

I had seen or heard nothing about my family for a long time, when, one day at the end of August, my Uncle Francois raced up on his bicycle with a bunch of purple and white dahlias in the basket. He gave the flowers to Auntie Marie and the two of them whispered together, glancing towards me while they shushshushed. I wondered what I had done wrong. He called out, “Get ready. Your mother coming for you.” Auntie gave me one of her precious brown paper carrier bags. I put my clothes in it and waited. When I first saw my mother, I thought it was my aunt, her twin sister. Her long hair was gone; she looked older, more nervous than I remembered. She looked at me, said, “You got bigger,” squeezed me tight, patted my head, sat me in the back seat of the waiting car. We were taken to La Seiva, where my grandmother had moved without my knowing. Two men were waiting there for me: a photographer and a reporter. The results of the Exhibition exam were released to the newspaper and my mother had been tracked down through my Uncle Francois, whose flower-growing business everybody knew. I was to be photographed and interviewed for the next day’s Guardian because I had come first in the College Exhibition exam. Afterwards, Uncle Francois bought a jug of coconut ice cream from a passing vendor’s bike-cart, a special treat for me.

The news must have reached our father somehow, because that night he arrived in La Seiva. He and my mother spoke in the gallery for a long time. I don’t know for sure why they decided to get back together. Maybe the people to whom we children had been sent had agreed to keep us only for the school holidays. I also think that when the news of my success became public, our father would have felt ashamed among his friends and co-workers, shown up as a man who didn’t take care of his children. Our father said he had found somewhere for us to live. He took my mother and me to see the place.