Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

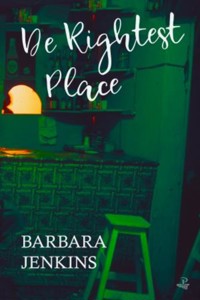

Indira Gabriel, recently abandoned by her lover, Solomon, embarks on a project to reinvigorate a dilapidated bar into something special. In this funny, sexy, sometimes painful and bittersweet novel, Barbara Jenkins draws together a richly-drawn cast of characters, like a Trinidadian Cheers. Meet Bostic, Solomon's boyhood friend, who is determined to keep the bar as a shrine; I Cynthia, the tale-telling Belmont maco ; KarlLee, the painter with a very complicated love-life; fatherless Jah-Son; and Fritzie, single mum and Indira's loyal right-hand woman. At the book's centre is the unforgettable Indira, with her ebullience and sadness, her sharpness and honesty, obsession with the daily horoscope and addiction to increasingly absurd self-help books. In this warm, funny, sexy, and bittersweet novel, Barbara Jenkins hears, like Sam Selvon, the melancholy behind "the kiff-kiff laughter", as darkness from Indira's past threatens her drive to make a new beginning.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to special gifts that kept on giving…

My first thanks go to Rhiannon, Gareth and Carys who, every day and in every way, are the wellspring of my enduring joy in just being alive. Love. Love. Love.

Then there’s Bernardine Evaristo, Ellah Wakatama Allfrey, Jennifer Hewson, Funso Aiyejina, Lawrence Scott and Jenny Green Scott, who variously mentored, edited, commented and guided this work through its many drafts. Huge thanks.

Alex Smailes and Gareth Jenkins of Abovegroup and Melanie Archer. Immense gratitude for the cover photo and design.

Helen and Andy Campbell gifted me the use of their Tobago flat, an escape from the insidious seductions of Trinidad and the internet, to get on with the serious business of writing and sea bathing. Couldn’t have done it otherwise. Greatly appreciated.

My book club buddies and many friends who kept asking, so how the novel going? That splinter in my sole spurred a sprint to the finish line. Massive thanks. Hope you don’t mind if I don’t let you know what I’m up to next rounds, OK?

To Bocas Lit Fest – your very existence, your boundless energy in making real what once could only be imagined; they sustain and nurture me in this late life outing. I owe you. Big time.

To normal, everyday Trinidad, whose unique genius is to unceasingly produce real life stories that are too unbelievable for fiction. Carry on regardless.

Finally – Dear Hannah and Jeremy, Peepal Tree Press, bravest, most aware publishers, ever. Thanks for your faith in me and your courage in taking me on. Again.

The Hollick Family Charitable Trust and the Arvon Foundation put their trust in the uncertain possibility of this book by their generous award of The Hollick-Arvon Prize 2013. I am humbly grateful.

BARBARA JENKINS

DE RIGHTEST PLACE

First published in Great Britain in 2018

Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

https://www.peepaltreepress.com/home

https://www.facebook.com/peepaltreepress

https://twitter.com/peepaltreepress

© 2018 Barbara Jenkins

ISBN Print: 9781845234225

ISBN Epub: 9781845234485

ISBN Mobi: 9781845234492

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may bereproduced or transmitted in any formwithout permission

CONTENTS

Prologue: I Cynthia – Belmont Maco

PART ONE

1. Float to Loftier Altitudes

2. A Place of Scattered Desperation

3. Soulmates

4. Get Up, Stand up

5. Making as Eef

6. Correct Costume Conquers Challengers

7. Licensed to Sell Spirituous Liquors

I Cynthia – Belmont Maco

PART TWO

8. The Gift with Unalluring Packaging

9. A Good Friday

10. Everybody Needs Somebody

11. Fortune Favours the Fearless

12. A Large Circle of Keys

13. Neptune in Pisces

14. Don’t Deal

15. Fraught with One-Upmanship

16. Routine, Rhythm and Ritual

17. Strategic Battles

18. Hold to Your Convictions

19. A Quiet Place

20. Glad Tidings

I Cynthia – Belmont Maco

PART THREE

21. Madonna Mashes Mapepire

22. Inner Knowledge

23. Lunar Eclipse

24. Wet Paper Can Cut You

25. Karma

26. A Certain Amount of Harmony

27. Think of the Consequences

28. Deep in Thought

29. Home Sweet Home

30. Muddy More Water

31. Fool Yourself

32. A Long Range Vision

33. No Chick Nor Child Nor Parrot-on-a-Stick

34. Live, Love, Be Happy… Irregardless

I Cynthia – Belmont Maco

I CYNTHIA – BELMONT MACO

On the day I born, overhearing the Rediffusion that the neighbour turn up full blast so the whole yard could enjoy he good fortune – he being the onliest person in the yard to have radio – mih Marmie hear a nice song she never hear before and it go like this: Who is Sss… what is she? That Sss… is all she make out of the name, because right at that instant, Dou-Dou, she Martiniquan pwatique, bawl out from the lane, Proviz-yoh, proviz-yoh fray.

Marmie rush outside. She have to choose plantain to pound and dasheen to boil and fresh seasonings to put on the carite she buy from the fishman that same morning self. The first belly pain slam, whattam! And is radio-neighbour-self who have to run up the lane to get Nurse Brooks. Nursie rest she two hand flat on top mih Marmie stretch-out belly. She feeling round and round. She ent saying nothing. Mih Marmie ent have no experience in these matters, but when she seeing how Nursie only shaking she head, how she only pushing out she mouth, Marmie sensing things mussbe not right. Nursie saying to radio-neighbour, You stay right here. Then she say, This looking like real trouble, oui. She tell him, Do quick and run up by the Circular Road. Get a car. This is Colonial Hospital business.

See the three woman park up outside on the road, waiting for radio-neighbour to come back with the car. Dou-Dou, marchande, market basket balancing on she head, shifting from foot to foot. She don’t know how to leave; she don’t know how to stay. Nurse Brooks, big black midwife bag in tight grip, head jerking left to right to left like a frighten chicken looking to get to the other side of a busy road. And mih poor Marmie. She prop up on galvanise fencing, she two hand holding up she belly, like if is a big heavy pumpkin she carrying and she fraid to drop it and it buss open. Oh god, oh god, she saying. She bending over. Oh merciful father in heaven, she bawling. She squatting down on the road. Uh-uh-uh. She calling, JesusMaryJoseph. Now is only a whimper: OhGordOhLord OhGord! And with that, I step out, foot first, right there on the road. Uh huh. Right on the crossroads. Right under Eshu watching eye. Yes, Eshu-self looking on as mih two foot touch the pitch road. Watch mih. I ready to travel. I ready to carry news. I ready for the road.

When she hear is a girl she make, Marmie decide there and then to call me Cynthia. What else girl name the man could be singing about that early morning? What other name starting with a Sss? What happen, though, is that when the christening party reach the head of the line Sunday morning, when I is six weeks old, Father Liam Pádraic look for my intended name in his book of saints. He look, and he look, and he look again, but nowhere can he find the name Cynthia. And in any case, he say he can’t baptise children who born out of holy wedlock on the Lord’s Day. With that he send back mih mother, Thalitha Charbonné, mih godmother, Angela Del Pino, and mih godfather, Sonny Deyal, telling them to come back next Thursday, the day for bastards. Which by luck and chance also happen to be the day of the week I born on. Thursday. The day for the child who have far to go. It give Father plenty time to look up in his older saints books and find out who is Cynthia and what is she. St Cynthia is an obscure third century Catholic martyr, who was tied to a horse by her heels and dragged through an Egyptian city for refusing to worship idols.

Well. Well. Well. Look at mih crosses! Three of them! Is like I is Calvary self? First, Eshu is my orisha, and he have plans for me – messenger, carrier of news. Second is the Thursday borning – traveller. And third is mih baptism name – Cynthia. Listen how that name they give mih sounding like if is two half: Sin and Thea – each half at war with the other. First half, Sin – to do with the Bible man-god thou-shalt-not commandments. Second half, Thea. I find she is a woman-god who doing whatever she want and letting you do what you want, too. Yuh business is yuh own business. So, from early on, mih destiny is to be open to everything and everybody. Ambidextrous: I using mih two hand equal-equal. Ambivalent: I seeing all two, three, four side of every argument; I give the devil his due; I turn the other cheek, and is I who facing all two direction on a journey. Don’t ask mih to judge nothing. Put mih in front any competition – Carnival costume, pan side, Easter bonnet, poetry, baby, dog – no matter what, I find something equally good in everything. Up to me, everyone done win already.

If anybody ask, so where Cynthia is? somebody bound to answer, check out De Rightest Place. That is where to find mih when night come. I Cynthia, right there. I spending hour after hour drinking straight coconut water with a curl of lime peel, while everybody around me getting sweeter and sweeter, higher and higher, louder and louder. Empty rum bottles piling up and Bostic tired fulling up beer chiller and ice bucket as the night wearing on.

And what I doing in De Rightest Place? I minding mih business. And what is mih business, you might arks? Mih business is minding other people business. They call me the Belmont Maco, the see-all, hear-all of the village. Watch mih. I listening to all the talk, all the jokes, all the story that people relate.

Is Eshu-self put mih so when I born under he eye. Eshu, the one they say connect up the world of awakeness with the world of dreams, the one who link here-ness with there-ness. Eshu, spirit messenger of the gods, and I Cynthia, living messenger of De Rightest Place, ready to carry story from one to the next, like Eshuself. I listening to everything people relating, yes, but I listening even harder to the stories they not relating. Under the waves of sound vibrations, I picking up the heart vibrations and the soul vibrations. I does travel from what yuh seeing to what hiding behind what yuh seeing, from what yuh saying with yuh mouth, to what yuh telling yuhself in yuh head, from yuh wide-awake self to yuh deepest dreaming self.

But while is me who know all and could tell all about the people and things going on in De Rightest Place, I Cynthia choosing to follow Solo example. Yuh see, most nights when he was here running things, Solo uses to have a small side playing panjazz. Everybody in the little combo getting a solo spot to riff and ramajay while the other musicians standing back. But check them – they supporting, they encouraging, they keeping the thing going. Everybody waiting fuh as and when they get the feeling to find they own space to do they do. For who decide which instrument, which player, yuh mus’ hear and which yuh could do without?

And who is me to turn mih back on the establish custom of De Rightest Place? When it come to people business, who is to say who story to tell and who story to leave out? Everybody getting a chance to take centre stage and give they side of the story. Even the pub itself. Yuh ever hear the saying Walls have ears? Well, the walls of De Rightest Place does hear everything that going on inside a there. If walls have ears, well then, it must have voice too, or else pressure inside would build up so high, head buss open and roof fly off.

Only thing is, the walls here build longtime. Old man McDavidson build this place for Florence, he onliest daughter, who he didn’t let nobody get marrid to. Miss Florence school uses to be right here. With the rod of correction, lil picky-head chirren get bad English knock outa dey head and proper English knock in. Miss Florence, poor thing, musbe rolling in she grave to see how, after Independence and we own-own University, “bad English” get promotion to “home language” and “creole” and “patois”. So, under Miss Florence instruction, is not only ole-time budding civil servant and politician, is the building self that learn to talk plenty-plenty proper English. So, when yuh see De Rightest Place trying its bes’ with using The Queen’s English, beg pardon, I hope yuh try and unnerstan where it coming from. Is the burden of history that real hard to put down.

As for me, the Belmont Maco cyah get leave out. I will step in and reveal as and when I see fit. Yuh see, yuh cyah always trus’ people to tell the whole truth when is they themself that involve. I take refusing to worship idols very serious. As far as I concern, No Man is an Idol. And is not I Cynthia, nah, not me, is this story, the story about De Rightest Place that will get drag through the whole a Belmont.

So let we begin. Who we bringing on stage first? No question. Clear the way for none other than the bosslady of De Rightest Place, the woman who everybody does call Miss Indira.

PART ONE

1. FLOAT TO LOFTIER ALTITUDES

Is fifteen months to the day that Solomon Warner gone to Caribana and not come back. See y’girl Indira prop up on a heap of pillows on her side of the bed. But she can’t stop her eyes slanting over to the picture on his bedside table. Opening night party of De Rightest Place. The two of them hugging-up, smiling for the camera. A stray blue streamer draped over his right shoulder. Her left hand caught in the act of reaching for it. She stretch over and pick up the picture. She looking at it hard-hard. She say, Solo man, the time has come for me to accept that it’s all over. Because, while it’s true they wasn’t married in any legal sense, it looking like not in any other sense neither, since he could pick up himself, take off to Toronto with the steelband, and not come back with the others.

Was only Skeete, the iron man, who tell her that Solomon say he going solo. It really eat her up how Solo himself not even once try to get in touch with her. Not even a little Dear John, oh how I hate to write letter. She telling the picture, Solo man, how could you not send even one word, one paltry word, to say whether you’re dead or alive? After all we’ve been through together? Seven and a half years. She rest back down the picture. She close her eyes. She say, If I don’t recognise this is it, that I’ve been bit, this could drag on and on and I’m left here, lingering in limbo. Chuts, I’m vex with Solo, but I’m also sad. Regretful, but not bitter. Abandoned yes, but I’m not destitute. At least that is what Indira trying to talk up herself into believing this Sunday morning. She figuring, too, how she going to move on. She open back her eyes. From whence cometh my guiding light?

Y’girl bring to mind a TV show where an expert was giving advice, brandishing his book, Everyday Economics for the Financially Fraught, like if is some kind of Bible. It really rankle her that advice about how to use stale bread in forty different ways always coming from people who don’t even eat bread – bagels and croissants are much more to their taste. But anyway, the TV expert say that first you make a list of your assets and, while she suspicious of such advice, because of where it’s coming from, at least it’s a start. So Indira find paper and pencil and she quick-quick begin to make a list.

A List of My Assets. First asset, she say, is herself, so she write down: ME. After all, yourself is all you have when everything is gone and, although everything is not gone, it’s good to look at yourself and see what you have that could work for you when the chips are down. It’s not as if it’s the first time she’s down on her uppers and has to start from ME. So saying, y’girl sit up a bit straighter and glance across at the big oval mirror facing the bed. She lift an appraising eyebrow, then she add: young, good-looking, nice body. She look at her hands. Nails nicely done, sure. French-cut, white tips. But the hands are rough and red, scored and blotchy. Calluses on the palms. Was a time when she used to wear gloves when she’d be seen in public – though she’d turned that to her advantage in the retro playboy-bunny years when those long, above-elbow, black gloves was the signature nightclub hostess costume. She never fool herself as to the real reason. She look at her hands again. Battle-scarred. She slump down on the pillows, close her eyes a good while. She sit up, shaking her head. She look at what she’s written – young, good-looking, nice body.

What next? Bright. Though how bright you could be when your man standing in front of you packing for Caribana in August and putting sweater-gloves-snowboots-coat in his suitcase, telling you the internet say it cold no arse in Canada, and you only asking him if he have his creditcards-passport-cash-phone? If you can’t read the writing on the wall… But she still leave bright on the list.

Another asset pop like fireworks in her head. Blink, blink, blink go the eyes. She bite the pencil, chew on it a bit, and, after a little weighing-up, she write down: White. There. She’s committed it to paper. But she still feeling she must debate with herself what she can’t say aloud. The asset value of white. C’mon, she saying to herself. Don’t be coy. Admit that white is the default skin colour for global acceptability. It is the get-outa-jail pass, the win an extra-throw-of-the-dice. Yes. It’s true. Take her, for example. Living in Europe, no one questioned her right to be there. To have been born in India was interesting; her singsong accent was charming; even her name, so foreign, was unusual. But she could blend in, go anywhere without alarms going off. And though here, in this country, she stand out, it was in a good way. People look at her and immediately assume she’s well-off, has access, is deserving of deference. Blonde, blue-eyed, white. A veritable Holy Trinity of Privilege. Can’t deny. Security guards bow and say, Ma’am, and open gates. It certainly gives you the edge, whether with barman or banker, police or politician, lunatic or lover. Not at all bad for someone who is marginally poor and lives in less-than-desirable Belmont, who lived with a black, pub-owning Rastaman musician.

But, hang on; waitwaitwait a minute, she think. Whose labelling am I adopting? I’m fooling only myself to call Solo black in this country. That’s Europe; not how it is here. In this place, Solo red, up the scale by several notches, just below white and feel-they-white, somewhere in that jostling, fluid middle space along with light Indian, wealthy dark Indian and educated brown.

That whole If yuh white yuh right situation wasn’t always so with her. There was a time, long ago, when her being white, its very desirability, wasn’t good for her at all. When she was young. Too young. Defenceless. She hasn’t forgotten, but she doesn’t want to remember. Not now. She’s not going there. Right now, right here, in this country, white is an asset. It has currency. She can’t say it aloud. But she can write it down. White.

She tell herself, she should add honest to the list, because whitepeople in this place never want to admit they have privilege. No, no, no. In fact, they like to make out that they’re hard done by. True. Take her friend, Suzanne. The one who says her family is French aristocracy, who came here with the Cédula de Población. The family tree hangs on her living-room wall. You look at it and is only French names and cousins marrying cousins and Compte de this and Compte de that. When Suzanne and her family get together for brunch on Sunday after Mass, the talk is all about the good old days, growing up on the fifteen hundred acre cocoa estate, Qui Rit Bien, that the ancestors bought with the Emancipation compensation they got from Westminster. What does the name mean? I ask her. She laughed. It means Who laughs last laughs best.

Yes. Well, one day, just last week, Suzanne is doing one hundred and twenty in her Mercedes, zooming past the Beetham on one side, the stink La Basse on the other, when a traffic policeman overtakes and flashes her down. Madam winds down her window, tells him that he should bear in mind that they, that is whitepeople, is an endangered discriminated-against minority in this island. And he, the stout, ebony policeman, so flabbergasted, he stands like a statue next to his motorbike while Suzanne winds up her window and speeds off.

But y’girl Indira is saying to herself that she’s too smart to get suckered into that kind of mindset, because she, Indira, proud to declare to any and every body that she is not from here. And furthermore, though she and the local whitepeople share the same skin colour, she doesn’t share with them their burden of selectively misremembered history, and so she writes down honest.

What else is there? Hmmm… maybe it’s time to move on from the ME-myself-and-I concerns to more material things. She’s looking around the bedroom. There’s the clothes, the shoes, the handbags that filling up wardrobes in every room, but she’s not about to do an inventory, so she just write Plenty Clothes etc. Solo left a whole heap of things behind, and, since it’s looking like he managing quite well without them, she supposes they must be her assets now – but she’s not business with such foolishness. One of these days she will ask Bostic to pack up Solo’s personal effects and put them in the storeroom. Give her some breathing space.

Next: Car. A twin cab pick-up that Solo use to transport goods for the pub. The pub of course! The PUB! De Rightest Place. It’s running on autopilot under Bostic since Solo gone. The few neighbourhood hardcore customers still there – you could even say they’re living there – but from her vantage point, the upstairs bedroom window, she’s seeing fewer and fewer people dropping in. It’s like the spark to attract people gone. So, she has the pub, but it needs attention. And direction. Looks like Bostic is happy for it to tick over, but that’s not good enough. She will have to nudge him or seize the reins herself.

What else? Yes, right here, right where she is, the apartment upstairs the pub, that she and Solo call home for years before he gone. Two more – Apartment, PUB! This building is the biggest asset of all. She have to rouse herself, make a critical assessment of it, see how it’s really going and what it could do for her. No half measures. In for a penny… With that impulse, Indira get out of bed, throw on a wrap and go downstairs to take a serious look at the building. Outside, on the concrete forecourt, y’girl standing with her hands on her hips, looking hard at the building. Who could’ve guessed how things would turn out from the first time she saw this place? She was home, busy-busy. Big pot of pelau on the stove. Broom in hand. Phone rings. It’s Solo. Come now, come-right-now, his voice excited and urgent. There’s something I want you to see nownownow.

She turn off the stove, tie on a quick head-tie, divert a route taxi to the Belmont address Solo gave, and jump out when she spotted Solo’s big rasta-stripes tam. He’s standing next to a Chinese young feller outside an old rundown corner-shop. No name, no big sign advertising Broadway cigarettes or some such, like other groceries. Only a faded paper poster stuck up on a wall for JU-C Beverages, and a small sign painted on the front wall saying:

HOWARD CHIN HONG

LICENSED TO SELL

SPIRITUOUS LIQUORS

UNDER A GROCERY LICENCE

The paint on the wall beige and peeling, the plaster chipped and flaking off. The floor, inside and out, bare concrete. A tall wood counter. BRC burglar-proofing between long-gone customer and erstwhile shopkeeper; cut-out gaps for passing goods and money through. A dingy brown cotton curtain sagging from a relaxed spring rod spanning the doorway leading from the grocery to the back store. The back store so dark she could barely make out boxes, crates, tins, bags, piled high. Up a ladder through a hole in the ceiling to the attic upstairs, daylight threading a feeble path through dust-caked window panes, and, when they walking careful, careful, along the beams, bat guano, rat droppings, mouse pellets, cat dung, pigeon poo getting stirred up on the floor making her so sneezy-wheezy that they had to come back down quick, weaving their way through drooping cobweb drapes.

But the place looking solid – solid structure, solid location, and she agrees with Solo that it has potential. But that was after they got home and discussed the what and how and the why, but not the when of the decision to buy the place because the when was immediately, Now-for-now, said the Chinese young feller. He had to go back to university in Tallahassee where he’d come from in a hurry when his grandfather’s will was probated and he found himself sole heir to the old grocery he hardly knew as a child. His own father had leapt up quite a few rungs on the merchant- class-ladder by opening a factory making breakfast cereals in the heady early years of the Independence drive for self-sufficiency. So the grandson, having no sentimental attachment to place or person, wanted to sell the place quicksharp, and Solo was equally anxious to set himself up as Proprietor of a Pub.

Hang on a minute. A pub? It’s pub you saying? Indira ask. So why do you want to set up a pub? Why not a creole restaurant? People are always wandering around like bachacs looking for food and we could get somebody to cook, easy, easy. Or you could even convert it into two apartments, one for us to live in upstairs and the downstairs to rent out? But Solo want to show his father, God rest his soul, that it have more ways to skin a cat. When he start playing steelpan as a boy his father tell him, You see this steelpan thing that taking up all your time? Well, is a hobby, not something to take serious, and he pack Solo off to Dublin to study medicine. But he take up playing pan in the pubs at night and he find he most comfortable with himself on those occasions, so he drop out of med-school and start touring, playing gigs with a small side and now he want to recreate that music pub atmosphere right here in this place where people could lime and listen to live music and feel nice and mellow. He using the money his mother leave him when she die, right after she inherit from his father when he die.

So it’s payback? You want to get back on your father for cutting you off when you dropped out of medical school? It’s revenge that’s motivating you? Solo say, no, no, no. Is for me to get the satisfaction of doing what I want, show the old man spirit that I could make a good living and a life doing what making me happy, same as being a doctor made him happy. And now I find the rightest place to do just that.

Now here she is, this Sunday morning, standing outside the building, thinking about those early days, of how she and Solo built up the place so people come all week long to spend time with friends who are like family, but, thank the good gods, are not. Dealing with the place is not going to be too hard, she thinks, but what about my own self, what am I doing about making a break with the past?

The Sunday paper lying on the forecourt where the delivery driver throw it. She unroll the bulky package and riffle through the pages.

Gemini: Like a hot-air balloon, you will be able to float to loftier altitudes once you release the sandbags of bitterness, resentment and guilt. Purification is essential.

Purification is essential. Hmmm… Back in India, people do ritual purification in the river. Here they go to the sea for healing and for baptism. Water to purify, to renew. But Indira feeling she wants something stronger than water. Y’girl don’t want to just wash away the past. She reasoning that things you wash can get dirty and have to be washed again. What she wants is a real change. After the Noah Flood, even Yahweh himself said, not water but the fire next time. Fire changes things in a way they can’t change back from. Fire gives light. Light takes away gloom, dispels darkness. She’s glad that, as it so happen, now is year-end when the whole island looks to bring the light of fire to chase away darkness and sadness. She feels a lift of her spirits at the thought of fire. Purifying fire.

And so, on Divali night, Indira fill up some deyas with virgin coconut oil and put in cotton string wicks and lay them out in a big circle on the pub forecourt for herself and the bar patrons to light, making a ring of flickering flame as a sign of the unending chain of continuity in change.

Later, Indira make the All Souls pilgrimage to the cemetery at Lapeyrouse with Bostic, Cynthia and Fritzie, to light candles on the graves of their ancestors, because she herself doesn’t have any laid-to-rest in this place – or anywhere else she knows of. She gone too, by herself this time, to Memorial Park on Armistice Day, to hear the blast and echo of military gunfire rousing the souls of the slumbering war dead.

She feel she have to demonstrate to herself that she have the strength to surrender to the reality of her loss, that she owe it to missing-in-action Solo to celebrate the victory he won through his courageous charging into battle against other people’s expectations – hers too – to salute how he managed, against all odds, to triumph at making a living from making music in a pub.

After Indira do that exorcism, she walking back home to the apartment and the pub on that Belmont corner spot, making a reckoning of where she reach in her other journey.

She’d done her best to release the sandbags of bitterness, resentment and guilt, yet she’s not feeling as light, as relieved, as she thought she would be. She doesn’t feel as if she’s got rid of any weight. Instead, she feels she’s got no anchor, like she’s drifting.

It’s easy to count what you have, she thinks; it’s counting what you don’t have that is hard. Some things you’ve never had, so you don’t know the shape or the size or the feel of them. From the time she was born to now, so many shapeless spaces. There are the things she did have, some snatched from her, and some she carelessly allowed to go missing. Things she held so close that the holes they left are like the spaces from lost pieces in a jigsaw. You know the shape, you know the size, but you can only guess at the whole picture. Her life before Solomon has so many missing pieces.

It was what had drawn her to Solo, something about him that made her look again and then look closely a third time – his assurance, how comfortable he seemed in his skin, how confident in what he had chosen to do. A sure, secure rock she could hold on to.

Solo, I felt that at last I could stop drifting with every passing current. I told you that I had lived many lives before you, that I could be born into a new life with you. Solo, Solo, why you didn’t leave me something to remember you by, something living and growing? Why didn’t I tell you that, with a child of yours, I would have a chance of atonement for losing that other one? If we had a child you wouldn’t have disappeared without trace, your foot would have been tied. But those were things we never spoke of. Things you never asked about. In all the years we were together, you never showed any interest in babies or children, so it’s hard to judge what kind of father you would have been. You laughed when I showed you Perfect Partners Plan Parenthood. You said, let’s wait. Wait till we get settled somewhere. Wait till we have the time to do it properly. It’s a big decision. Yes, Solo, a big decision we never made. But, there were some good ones we did make. In the time we lived together in this island, I believed I’d found the place where I could belong, and share a life with someone who belonged to me. I thought I’d become the Indira that I could be. I saw a possible life I could hold on to and put my trust in. And now? How does that faith, all that trust hold up now?

Float to loftier altitudes.

That’s what she must do. Rise above her disappointments. A fragment of an almost forgotten prayer surfaces in her memory. Something about changing what you can change, leaving alone what you can’t – the wisdom is to know the difference. She can’t change the fact that Solo has gone. That she didn’t have his child. That she lost the one she did have. What can she change? She needs to think about that some more.

It is high noon when Indira reach home. De Rightest Place standing tall, solid. She look up the full length of its height. How easy to see everything in clean black and white terms in stark daylight. No blurred edges, no grey areas. No questions, only answers. No doubt, only certainty. She straightens her back and stride across the forecourt to place both her hands against the worn, wide, barred, double doors. The thick wood is cooler to her touch than she imagined it would be. She leans against the door for a while, allowing its strength to take her weight. How solid, how reliable it feels. She strokes the surface of the door with her fingers, the whorls of her fingertips, the lines of her palm, the calluses under her knuckles, searching, finding secret echoes in the wood’s curlicues and ridges, the knots and grain. De Rightest Place, she say, I’m talking to you. Yes, you. You who are so big and strong and tall. I am going to rely on you. And – I hope you’re listening good – you will have to rely on me. We’re in this thing together, you hear? Partners. You belong here and I belong here too. It’s de rightest place for both of us.

Y’girl turn away, walk up the stairs, turn her key in the lock and push open the door.

2. A PLACE OF SCATTERED DESPERATION

Indira flings open the jalousie windows and pokes out her head. The nearby clouds are plump, creamy-white, huddled, hanging like cows’ full udders. Craning her neck still further, she can just see, leaking at the edges, a rim of sky, the early morning thin blue of skimmed milk. Cows and blue are good omens, happy omens – puts her in mind of Lord Krishna and the gopis. The universe is saying: The time is right; make that fresh start. How? The answer reveals itself in the light of dawn: The only way to make a start is to begin. So, get going. Gird the groin for battle.

Twenty minutes later, shielded by the assertive armour of Yardley’s Imperial Leather, and bolstered by the morning’s horoscope: Centre your energy so you won’t approach any problem from a place of scattered desperation, y’girl is downstairs, surveying the interior of the pub.

Dear gods, what a sorry sight! In one corner, on the small platform, dusty stacks of beer crates jostle for space with a metal bucket, out of which a mop and a broom lean askew. Above, on the wall, a hodgepodge of gilt-framed photos. Solo in his prime, Solo with the band, Solo with the drop-ins, Solo and Bostic as teenagers, arms around each other’s shoulders, Solo and Bostic on opening night – Solo as patron, Bostic, barman – smiling as if they’d just swallowed both canary and cream, and she, herself, resplendent in African Trophy robes. Now, if you didn’t know, you couldn’t tell who is who and what is what, the glass so opaque with dust and grime. Hard to imagine that there, in that dismal corner, was the bandstand where Solo and musician friends would play for hours.

She closes her eyes to bring back how, on any given night, it could be Solo on tenor pan, Ming on keyboards and Andre on guitar, then Anthony on sax, and Colin on clarinet, each stepping up, segueing in and slipping away with the mood. Sometimes Solo would cede pride of place to the Maestro Boogsie, and he, the big man himself, would nod an invitation to anybody who looked interested to come and riff alongside him. And if Chantal there, or Natasha, either of them would forwards up. It could be the seasoned Mavis or Ella, or maybe one of the youngsters, Vaughnette or Ruth, who would take the mike and scat along. And it was play. Real play, like the way children play. For love, for fun, for enjoyment. People passing on the street, old ladies with young babies, big man and woman and even little children, would stand in the doorway like shadows, slide into the pub, make space to sit down, order a drink and everybody could dingolay to the vibe. And y’girl, Miss Indira, the I&I Queen as they called her, she would play too: The Hostess. Smiling, greeting, serving, presiding, dancing.

Solo was the magnet for all that, and now, with both north and south pole gone, is up to me, Indira Gabriel, to centre my energy, be my own Equator, and do the do.

Like we have a visitor.

The voice startles her out of her reverie.

Oh. Bostic. Morning. Didn’t hear you. Thinking about old times.

Uh huh.

But when old times gone, we have to deal up with new times.

It’s as if he hasn’t heard her. His attention is on inventory – replenishing the chiller, packing empties into crates, noting the spirits levels. Indira continues her survey – the torn and scuffed leatherette upholstered chairs, their peeling, black-painted metal frames, the scarred, water-ring-marked tables, the cracked and grimy tiles on the floor, the headgrease-stained walls, the ceiling, dingy yellow with ancient nicotine smoke. A pervasive man-caveodour hanging about the place.

How long has it been looking so awful?

Her arm traces a sweeping arc over the scene. Bostic follows her gesture, but his matter-of-fact expression doesn’t match her dismay.

Nobody bothering with that.

But, shouldn’t it be nicer? For customers?

They come, they buy drinks, they talk, they make joke, they play games, they go home. I clear up. I go home. Next day, I come. I set up. They come. They buy drinks. What it have to change?

Indira doesn’t answer. She walks around between the tables, pushing chairs into place, packing draughts boards and pieces into their boxes, collecting ashtrays. She notes the dust balls along the edges of the walls, the smears of dried spilled drinks on the floor, the dusty tables abandoned along the back wall.

How many people come here? On a normal weekday night?

He looks at her. His face is stiff.

Hard to say.

Take a guess. How many tables?

Five, six.

Weekends?

Couple more.

People stay the whole time?

Usually.

What they drink?

He turns away, carries on with stacking the chiller, filling crates, moving them to the storeroom.

Beers, rum.

Scotch?

Some.

How much does it make?

Bostic rests down the crate he was carrying with deliberate care. He turns his back to her, goes to the sink and washes a couple of glasses. He picks up a towel and a glass and turns to face her. He pushes one corner of the towel inside the glass and pays close attention to polishing it for a couple of minutes. Then he holds it up for inspection looking at her through the glass. He places the glass on the bar counter and looks her directly in the eyes.

It making enough.

Enough for what?

Enough for new stocks, bills, pay me and make sure you have enough for yourself.

Maintenance?

What maintenance?

Indira waves an arm over the room.

Repairs, painting, lighting, new furniture, cleaning…

Bostic goes back to the sink, picks up a rag and begins to wipe over the bar counter. He stops abruptly, flings the rag into the sink and slams his palm on the counter.

You have a problem with how I running the place?

No, not at all. I…

Is over a year Solo gone and I here by myself. You stick yourself upstairs. Never come down once to see how the place doing. I carrying the whole responsibility. And not a single word of thanks. Not one.

He walks round the counter and comes up close, staring down directly at her. His face is red. A vein throbs at his temple. His lips curl into a snarl.

Then all of a sudden, this early morning, you walk in here. Finding fault with everything. What really going on?

As if she has been struck, Indira reels backwards, staggers and collapses onto a chair. Her face flushes, then blanches. She drops her head into her hands. Bostic walks away, towards the bandstand. He yanks at the broom, clanking it against the metal bucket, He drags the tables away from the wall, scrapes the chairs along the floor over to one side, stirring up the dust of ages as he sweeps. When that half of the room is swept, he goes to the storeroom, gets a dustpan, sweeps the dust into it and tips the dust into the bin. He gets the bucket, fills it with water and mops the swept area. Minutes pass, a quarter hour passes, but Indira is not aware of time or of Bostic’s deliberately noisy busyness behind her. Her mind is blank. When his sweeping around her fails to rouse her, he knocks the broom handle against the bucket.

Excuse me. You are in the way.

She looks up at him, her face showing no sign of understanding. He continues.

You could sit somewhere else? I want to clean here now.

Indira gazes around as if she’s just woken in strange surroundings. As she stares at Bostic, a small furrow forms in her brow. She gets up as if to leave. But instead of moving straight towards the stairs, she gazes around as if unsure of direction. Bostic sees her hesitation. He wonders why she doesn’t just go. Just leave and let him carry on with his work.

You going back upstairs?

Yes.

She says yes, but her mind still does not connect with where she is. She is not sure where to go. Then her legs take over, guiding her towards the stairs. She mounts them, step by measured step, goes to her room, and falls on to her bed. Her mind unhinges further from her body, drifting away, floating to another time long ago, another place far away.

The gold thread follows the silver needle that follows her hand, running its own heedless way across the sari, a spice merchant’s gift for his betrothed, the gold thread shimmying, shimmering through the fuchsia silk, iridescent as the wings of the dragonfly flitting across her view, drawing her eye and drawing her hand as she embroiders the pallau, her eyes, her hand, the silver needle, the gold thread following the path of the zigzagging dragonfly, straying from the set paisleys, flitting hither and thither every which way…

Ruined… totally ruined… Bad gurrl, bad gurrl, bad gurrl.

Indira sees, draped from a waist as lean and as mean as a pew, the long heavy silver rosary chain studded with jet beads, big and black as watching eyes. She fixes her gaze on the silver suffer-the-little-children Christ impaled on his own suffering big-man cross. She will not look up. She will not look at the thin pale lips that spit the words, the harsh bloodless lines that rasp the shape of the words over and over: Bad gurrl. She will not meet the cold blue eyes. She will not look at the white wimple drawn close around the face as hard and as white as a marble saint in the chapel. She does not feel the metal edge of the ruler that Mother Clement crashes down on to the knuckles of her right hand… Her mind floats away from Bad gurrl. Bad gurrl. Bad gurrl… A cold white marble hand waves the right hand away and summons the left… a matching pair of hands blooming instant crimson roses on the knuckles… That pair of hands made her a Bad gurrl today… danced her needle across the length of the silk, its threads spun by captive caterpillars, dropped in hot water to release their coveted cocoons. Her once-pale little caterpillar fingers… She looks at them, she counts each swollen one. Badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl, badgurrl… They are seared scarlet. Her penance for committing the mortal sin of tracing, with a silver needle and gold thread across shimmery silk, the dance of the dragonfly’s iridescent wings.

When she comes to from this memory-dream, she looks around. What is this place? Where is she? Does the bad gurrl belong here? Is she the bad gurrl? Her hands run over her body. They encounter the heft of her breasts. This is she. She is the woman now.

The weak light strained through gauzy curtains casts thin wavery shadows across the room. But wasn’t it bright and sunny before? Between then and now a gap of unreal time. She can’t remember what brought her here, to her bedroom. She closes her eyes and forces herself to retrace her waking day. Where was she? Downstairs. The pub. Bostic. Arguing. She left. Before it was done. Must finish it. Get it done. Once and for all.

Laughter and the clink of bottles rise from below. Can’t go now. Tomorrow.

3. SOULMATES

Out of a clear blue sky, she come in here, putting god out of her thoughts and start to find fault with me! The place looking awful. How much money you making? How many customers come in? How come it so dirty? Who she think she is? Who the hell she is anyway? A little nobody from nowhere. Nobody don’t know a damn thing about her. She say she from India, but Solo tell me he meet her in a nightclub in London. And what she was? Owner? Bosslady? Nah. Guess again. Exotic dancer! Uh-huh…

When Solo buy the old grocery, who he look for to help him renovate it? Me! Me and he working day and night. To-ge-ther. Is me, Bostic he put to run it. His first. His only-est choice. And in the meantime, what she was doing? Flitting all over the place. Flinging her bleach-blonde rasta-braids. Flirting with everybody. Musicians, customers, tout-moun. Miss I&I Queen of No Account!

Since Solo gone Canada, Miss I&I Queen never put a hand, never put a foot, never put herself out to come downstairs to even rinse a glass. Not once. Months gone by, she upstairs, sulking. And now, she ketch a vaps and come down here, throwing her weight around. I not answerable to her. When Solo getting ready to go Caribana, he say to me, Bostic, I leaving you in charge. You understand what this place means to me. Take care of it till I come back. When you coming back? I ask. He say, I don’t know. Maybe not for a while. You tell her you not coming back? No. This is just between you and me. And we go by the lawyer, and Solo hand me Power of Attorney. Nothing can be done without me. My agreement. My signature. That is how Solo and I does roll. Soulmates. You can’t take that away. Especially not some interloping Indira-come-lately.

From day one, I, Terrence Bostic, and he, Solomon Warner, were best friends. From that rainy September morning, when Solo and I were put to share a desk in the kindergarten of Tranquillity Boys’ Primary School, I think we sized one another up as rivals. I remember smirking at his Bugs Bunny blue lunchkit and flaunting my own red and yellow Star Wars model. But I have to admit he won with the pencil case and sneakers. Army camouflage print with magnetic clasp (thups, as it does itself up) easily outranks zippered (rrrrr, stuck, reverse, rrr, stuck again) pink peony print. And as for my Bata Bullets v his Adidas? No contest.

At recreation that first morning, we ran out together in the pouring rain to kick ball. A little classmate delivered a message: Teacher Mildred say come out the rain, now. Another message came. Teacher Mildred say, When she say now, is right now she mean. Then Teacher Mildred herself is standing in the classroom doorway, surrounded by a couple dozen jostling classmates, eager to witness one of life’s hard lessons: Disobey and You’ll Get Licks. It was the way the world worked at home, why not at school too? Smarting palms and up-welling eyes bravely, nah, stoically contained – together.

We pitching marbles in short pants; winning scholarship to Queen’s Royal College and going Saturday twelve-thirty Roxy double feature in long pants; running away from home Carnival time to beat pan in Silver Stars panyard; captaining football and cricket teams as rivals. Two cocksure handsome redboys, smelling ourselves as man from early, having to fight off girls who were conniving to catch one of us, till death do them and us part. My mother, Solo’s mother, both of them, drummed home the Thou Shalt Not Go Causing Distress to People’s Daughters commandment as we walked out our front doors enveloped in clouds of Brut. People’s daughters were the respectable light-brown Woodbrook girls. Our mothers didn’t explain causing distress, but fellers at school exchanged information and we learned what kind of girls we could safely tackle – girls from places like Belmont and Gonzales, glad that boys like us were paying them attention. Girls who already knew the ways of the world from the men around them and the bosses of the places where they worked. Girls whose families were quite accustomed to having distress visited upon them. For us, for Solo and me, those encounters were just another subject in our education on how to be men in the world.

One evening, we were over by him, watching an old Western video. About an Indian Chief. Cochise, I think. When the movie was over, Solo went to the bathroom and came out holding a little yellow and white cardboard box in both hands, like if it was a communion plate. His eyes locked into mine. He said nothing. His fingers pulled out the thin wax-paper wrapper. The box fell to the floor. He unfolded the wrapper. The paper drifted down. I could not move my eyes from his. He held the blade in his right hand, his stare not wavering one blink. He lifted his left hand till it was right in front my face. In one stroke, he drew the edge of the blade across the pad of his left thumb. Blood, bright red heart blood, sprang out of the slash and flowed along his thumb into his palm. He handed me the blade. I did just as he’d done. We pressed sticky thumbs together, clasping wet palms. Together, we said, Blood. Just like in the movie.

Through all those years, we were like see one, see the other, inseparable. Until Christmas of the year we left school.

He whistled our call to get me out to the front gate and we stood in the early morning chill on the pavement outside my house. He said he wouldn’t come in. He wasn’t in the mood for Christmas greetings. He handed me a letter. He bit his lips and looked away, but not before I saw his eyes were full. I read the letter and handed it back. When? I asked. He didn’t look at me. He looked up at the mist-shrouded Northern Range, as if looking at it properly for the first, and maybe, last time, said nothing for a long while, then said, Tomorrow. Neither of us said anything more. We didn’t hug. We didn’t shake hands. He wheeled his bike off the pavement onto the road, climbed on it and rode away. I imagined I saw water drops darkening the grey road, but maybe it was because my own eyes were blurred. I watched his bent back, the pumping motion of his legs, the narrow wheels on which he balanced, the white polo shirt billowing behind him, and while I wished that sail would blow him back, I knew his bike would turn at his corner and take him home as it had done a thousand and more times before. I stood there on the pavement unable to move as I watched him sail out of my life.

Solo’s doctor father had decided that Solo should follow in his footsteps. He arranged for him to go to Dublin. It’s your special Christmas present, said his father. Plenty boys would be glad for this opportunity. To make sure Solo actually got there, his father took him himself. I suppose he did not want to risk a repeat of the Arnold incident. Arnold Samuel, a schoolmate of Solo’s dad, was a legend to us boys, to our elders a warning about what wayward sons are capable of. The son of a prominent judge, Arnold was unwillingly despatched to London to study law. When the ship docked in Port Antonio harbour to pick up its cargo of bananas, Arnold jumped ship. Story goes he went to join the Maroons in Don’t Look Back settlement in The Cockpit Country. Dr Warner wasn’t taking any such chances with his only child.

And me? What do they say about a body that has had a limb amputated? It never stops feeling the missing part. For me, though, not always a limb. Could be eyes missing one day, and I’d be stumbling about, not seeing anyone or anything around me. Another day, hearing nobody, nothing. No taste for the things we used to do. No panyard. No football. No cricket. Instead, every rumshop in St James got to know me.

I think my mother understood. Malkadee, she called it. But when it lasted too many months, she got fed up. A big locho twenty-something man (how old you say you are now, boy?) still living in his mother’s house and showing no sign of making a move to get a steady career? She contacted a distant cousin who was building a house in the country. Make him work till he too tired to think. So it was lifting bags of cement and sand. Toting clay blocks and wood. Fetching buckets of water and sheets of galvanise. I learned carpentry and masonry. I worked till I was tired. But not too tired to think. When the house was finished I was back home and at a loose end again. Then wrestling became a big thing. Every week, the Mighty Ray Apollon and Thunderbolt Williams played to a packed, screaming Jean Pierre Complex. I was physically fit and I tried that too – for a while and with not much success, as my mind wasn’t in it.

My brother Stephen got married. He’d got his girlfriend pregnant. Aunties and uncles started asking me, What happen to you, boy? How you letting your little brother overtake you? I tried to make joke about it. Nobody ever asked me to marry them. But it did make me ponder. A wife. Children. Would that make it easier? Would that give a purpose to my life? But then, after three children, bam-bam-bam, last one a baby still, braps! just so, Stephen’s wife picked up herself and went to Canada to do a course. She sent him a letter to say she’s bettering herself and not coming back.

Terry will help out, our mother assured Stephen. Is not as if he doing anything he can’t leave. So I had to help out with driving children to school and their activities while Stephen was at work. My days and weeks and months and years rolled on, unremarked, like that. Then one nephew was old enough drive. That freed me from responsibility. I had plenty time to drink, to smoke whatever was available, time to do a bit of this and that, to drift in and out of the odd little building job, to work as a bouncer in the new nightclubs that were springing up everywhere, like fleas on a stray dog. All in all, looking back at that time, I don’t remember clearly where and when and with whom I passed my time. Half a life spent as a sleepwalking alcohol and drugs-fuelled zombie. There were days I would wake up in places I didn’t remember entering. Strangers shaking, kicking, shouting: Wha’ yuh doing here? Eh? Nasty stinkin drunkard. Get out! Get out!