Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

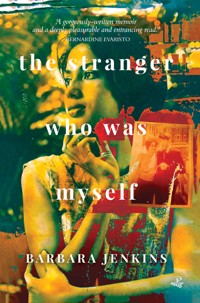

Barbara Jenkins writes about the experiences of a personal and family-centred life in Trinidad with great psychological acuteness, expanding on the personal with a deep awareness of the economic, social and cultural contexts of that experience. She writes about a childhood and youth located in the colonial era and an adult life that began at the very point of Trinidad's independent nationhood, a life begun in poverty in a colonial city going through rapid change. It is about a life that expanded in possibility through an access to an education not usually available to girls from such an economic background. This schooling gave the young Barbara Jenkins the intense experience of being an outsider to Trinidad's hierarchies of race and class. She writes about a life that has gender conflict at its heart, a household where her mother was subject to beatings and misogynist control, but also about strong matriarchal women. As for so many Caribbean people, opportunity appeared to exist only via migration, in her case to Wales in the 1960s. But there was a catch in the arrangement that the years in Wales had put to the back of her mind: the legally enforceable promise to the Trinidadian government that in return for their scholarship, she had to return. She did, and has lived the rest of her life to date in Trinidad, an experience that gives her writing an insider/outsider sharpness of perception. 'From her childhood in colonial Port of Spain, to becoming a migrant student and young mother in Wales and then returning to Trinidad post-Independence, Jenkins tells her own life story with the emotional sensitivity of a natural storyteller, the insight of a philosopher, the scope of a historian and the good humour of a Trini. This beautifully written and moving memoir will feel achingly familiar to anyone who knows what it is like to navigate race, class and girlhood while growing up in the West Indies, anyone who has ever felt like an outsider.' Ayanna Lloyd Banwo, author of When We Were Birds.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 729

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

THE STRANGER WHO WAS MYSELF

BARBARA JENKINS

First published in Great Britain in 2022

by Peepal Tree Press Ltd

17 King’s Avenue

Leeds LS6 1QS

England

© 2022, Barbara Jenkins

ISBN Print: 97818452325345

ISBN Ebook: 9781845235710

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any

form without permission

Love after love

The time will come

when, with elation,

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror,

and each will smile at the other’s welcome,

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was your self.

Give wine. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you

all your life, whom you ignored

for another, who knows you by heart.

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,

the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life.

— Derek Walcott

We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love. But always meeting ourselves.

— James Joyce, Ulysses

If you know whence you came, there are absolutely no limitations to where you can go.

— James Baldwin

We all have to make our own arrangements with the past

— Ian McEwan

For Sian, Paul, Jack, Skye, Hugo, Elle, John, Beatrix, Solomon and those yet unborn with so much love and gratitude for the gift of you

CONTENTS

GREET

The time will come

Door

Photographs

Bread

Welcome

Bookshelf

Wine

PEEL

Stranger

Arriving

Desperate notes

Love letters

Feast

Heart

Time

This is my arrangement with much of my past. With few exceptions, all the people mentioned here are real people I know as well as anyone can know anyone else. I’m not sure how much of myself I know after this exploration into the past.

GREET

Is there a way in which all of us are fictional characters, parented by life and written by ourselves?

James Wood

THE TIME WILL COME

I understand now what you saw when you looked at it. I followed your gaze as your eyes took in the white lettering on the two blue enamelled street signs set at right-angles to each other on a concrete post, the low wall curving round the two streets, the green twisted-wire fence that topped it, the gallery that mirrored that curve and the jutting bay room that anchored it on the right, the fretwork-fringed porte cochère, the little oval blue enamelled street number plate fastened to its front, the steeply sloping corrugated galvanize roof streaked red-brown by time, the finials at the ridge-ends pointing fingers to the sky: at each feature your eyes widening, your smile broadening. It is… it is… exquisite, you said. Exquisite.

I didn’t see exquisite. I saw an old-fashioned house built of the wattle and daub we here call nuggin, and wood too – wood floors, wood windows, wood partitions, everywhere wood, ordinary wood, a wood that looked solid until you touched it and your fingers felt no resistance, felt something thin like paper that you could punch through to reveal secret tunnels, branching and interlocking; a separate nuggin and wood kitchen shed outside; a separate wood latrine out in the back. Everything about it shaming and shameful. It did not have the tiles, the solid concrete blocks, the glass, the everything-anyone-needed kitchen, proper facilities like a bathroom with a shower and flush toilet. It wasn’t the modern everything I’d aspired to when I lived there.

Many years into the future when we had not just the one – she straddling your hip that morning as we stood on the pavement at the corner of Reid Lane and Pelham Street, Belmont – but three little ones, Sundays would find you donning your wide-brimmed burgundy West Indies cricket hat, piling a chair, a tripod and a camera bag into the car trunk. You’d be leaving home to trawl through the streets and lanes of Belmont, Woodbrook, Gonzales, Laventille, Piccadilly, Corbeau Town and beyond in search of suitable subjects. On finding one you would park, stand on the chair on the pavement and in the street, adding to your six-foot height for a better view, and methodically document on film – and written notes – whatever you could of it, so that over time you had a record of perhaps a couple of hundred or more of those fast-disappearing, exquisite houses. I would, on those Sundays, recall that love-at-first-sight moment when that future must have reached back in time to tap you on the shoulder, that day when you pronounced my childhood home exquisite.

In the years before that day, those early years of our life together far away from here, I hadn’t told you anything about the house where I grew up. I don’t know why, but somehow it had never come up in conversation. Did it seem as odd to you then as it now does to me? After all, I knew your family home and there must have been lots of opportunities for me to make comparisons or reflect aloud about my old home. But then again there was so much about me, about my past, that I didn’t talk about, that you didn’t know about even after the almost nine years we’d been together. But that day we were there and I was glad you could find out for yourself all you had perhaps silently wondered about my old home and, perhaps, about me.

The red concrete steps leading to the gallery, the green sweet-oil tins lining the steps, were as bright as if Marmie had painted them the day before, but the palms standing in the tins, their branches withered brown and brittle, told a different story, a story of Marmie’s absence – as if the deep grey dust that registered the soles of our shoes in the gallery, like a burglar’s shoe-print in wet soil outside an open window in an old-fashioned whodunit, wasn’t clue enough. I marvelled at how excited you were to be there, how much you wanted to explore, to see everything, anxious to ask me questions and get answers about the life of the house, my life in the house. But oh, how I now regret I didn’t try to match your enthusiasm. I felt heavy, as if the weight of the empty present and the too-full past had seeped from the very pores of the house to fall on my shoulders, squeezing all vitality out of me, rendering me silent, dull.

Shall we go round the back? you asked. We went down the steps and there, walking past Marmie’s front garden, a sharp burst of minty fragrance distilled from her chrysanthemums dispelled my churlishness. I smiled up at you, you squeezed my hand, and it was with a lighter heart I continued along the side of the house, stepping on moss cushions, deep and springy from the lack of human tread, rounded the corner, and there we were, in the backyard.

The back doors of the main house were bolted shut, but, across the yard, the kitchen, lacking doors, was wide open and out of that doorway there hurtled a screeching something. The apparition landed on the top step of the house, its plumage so black, so glossy, it gleamed purple. It shook a cape of gold from its crown, extended its wings like one of those birds of prey on a coat of arms, stretched its neck to the sky, lifted its head and trumpeted a burst of territorial crowing. At that summons, a fussy, compact little brown hen emerged from the doorway and around her peep-peep-peeped three or four yellow chicks. Remember how our little one wanted to get closer, to pick up one of the chicks, but I was too afraid to let her? That cock’s crowing was not a warm welcome, not with those powerful wings that would allow him to fly at us like a real bird, not with those calculating yellow-ringed eyes beneath that scarlet comb carried like a triumphant warrior’s crown, blood-red wattles swaying under his chin, not with that dagger of a beak and heel-spurs like drawn knives.

Marmie had always had a few fowls scrabbling about in the yard, but she’d been gone such a long time that these could not be ones she’d left; these must have been several generations down the line, and without Marmie there to scatter corn on mornings, I guessed that each new generation must have got fewer and fewer in number, reverting more and more to their original wild state. They’d survived through that ceaseless peck-peck-pecking in the ground that comes instinctively, feasting on their natural fare of insects, lizards, frogs, congarees and worms. I’ve seen chickens catch butterflies and cockroaches in flight – the meal in flight, I mean, not the diners. I remember Marmie opening a drawer and finding that a mouse had nested there, taking the drawer out into the yard and tipping it over. The chickens, with a mad fluttering, had scrambled towards the shredded paper, old Christmas cards, rubber bands and bits of geometry tin contents and, scratching through these, revealed a half-dozen or so squirming pink blobs, like animated cartoon marshmallows. They skewered them with their beaks, lifting their heads, and swallowing them whole. These now in the yard hadn’t starved, they weren’t homeless, they’d adapted to change. I thought about that for a while and it seemed to me that whatever resilience and acumen it requires to take an evolutionary backward step in one’s habits, and learn to look after oneself in changed circumstances, these chickens certainly showed they had it.

I’d left a home far away where I was happy and comfortable and returned to this home of my pushed-aside past in this strange yet familiar country. I hadn’t come back alone. I brought you and her, my family – my precious other selves. To you and her everything about this place, this country, was new. I looked at the fowls, who by now had gone about their own business as if we weren’t there, and I wondered whether I, too, had hidden in some primeval part of my being the endurance, the ability to become as adjusted as they to this place where we found ourselves. I wondered even more how you, how she, how we, would adjust.

Back on the pavement, I took a last look at the house. It was locked but it wasn’t abandoned. In it lived my life from girl to woman. In it, too, were Marmie, Annette, Carol and Tony. There was my grandmother, my aunts and uncles, friends and family, neighbours. There was Pappy too. This is the house that grew me, and it is to all that happened while I lived there, and all that I learned when I lived there, that I must return if I am to make sense of who I was then, who I am now, and how I have become myself.

DOOR

Pappy asked my aunt’s husband to tell me that he was going to sell the house. So what about Marmie? I asked. He replied that Pappy said that since it didn’t look like she was coming back, he had to make a decision. What if she does come back? Where would she live? She could decide for herself, he said. Pappy would give her half of what he got for the house to do with whatever she wanted.

It was the second week of my return home, July 1971. My husband’s work permit hadn’t yet come through and he was under threat of deportation, even though he had a government job on a three-year contract. I was due to take up teaching in a matter of weeks, a requirement of my scholarship contract. We were staying with my aunt, my mother’s sister, at her home, with six of her seven children and her husband, Pappy’s go-between. We were looking for a place of our own to rent while still searching for suitable day-care for our two-year old. We had no car since the Hillman Hunter we’d bought new with our slender UK savings and a local loan was stolen a couple of days after we’d visited the house in that first week of our arrival. That’s how things were with us, with me, when Pappy dropped on me, not in person, but through an intermediary, the news of his intention.

I hadn’t seen my old home for the decade of my life away. It held the memories of my growing years, and now, before I could even properly reconnect with it, Pappy was going to sell it. At the time I didn’t question why he’d waited for my return to do this. I had been away for so long that I was out of touch with family and with people’s ways of thinking and doing things, so much so that I was effectively a stranger. I suppose I may have taken it for granted that Pappy wanted us all, all four of our mother’s children, to be present and in agreement with his plan before he acted. It was a quick and naïve assumption, and it was only later that I saw how much I had erred.

I mean how present were we as a collective called Marmie’s children, as collaboratively concerned with seeking our mother’s interest, anyway? I asked them, my siblings, how they felt about Pappy wanting to sell the house? Well, it’s his. He can do what he wants. That seemed to be their position and how could it be anything else? I’d left Marmie with her children as a unit, but I had come back to find her gone and her children scattered. Annette and Carol were married with husbands and children of their own, both living in Diego Martin, some distance from Belmont, and Tony, now twenty-one, lived nearby in Belmont with family friends, and there was I, newly arrived and not alone, staying with family until we found a place of our own. I didn’t rally them, my two sisters and brother, to look more closely at the implications of our easy dismissal of interest in Pappy’s intention. They had their own lives to get on with and it could be that they felt some relief in imagining that this house sale would sever their last link to him. After the house was sold, it became clear to me that I had walked into a trap, a set-up, contrived and carefully laid by Pappy himself, very likely with my uncle-in-law’s connivance, and that I had, by my quick and easy agreement to the sale of the house, allowed myself and my siblings to be accomplices in defrauding our mother of what was her due by virtue of her many, many years of investment in her home.

I was eleven when we moved into 74 Pelham Street. From the road, where the open-tray Ford truck pulled up with us and our belongings, my mother and we children saw a cream, single-storey house with a long narrow-roofed extension over the front path, steps leading up from the path to a wide gallery backed by three sets of double doors, with big clear knobbly-patterned glass panel inserts. 74 Pelham Street also had another address, 10 Reid Lane, for it was a corner house, and the gallery wrapped round to give views over both streets. I wanted to believe, to hope that all of it was ours as we walked through the gate, but Marmie didn’t go up the steps to the gallery to enter the house by either of the double glass doors, or by the solid wooden door to the bay room. We children followed her round a path between the side of the house and a tall galvanize fence that separated the house spot from the next-door house, past the bay room to the backyard. Marmie handed baby Tony to me, and we children stood in the yard while she climbed four plain concrete steps to a closed door. At the top step she unbolted the door, which turned out to be only the top half of the door. She swung it open and latched it against the outside wall. She then reached in to unbolt the lower half. She swung it back and walked in.

This was our future home. Two rooms at the back, behind the bay room. Those two rooms were to be our everywhere space, for sleeping, sitting, eating. Everything else we needed was shared with the other occupants of the house. How it was worked out that ours was the right-hand part of the kitchen shed behind and separate from the house, and the right-hand stall of a two-compartment, single-pit latrine outhouse further behind, I don’t know; perhaps we simply inherited those arrangements from the former occupants of our part of the house.

There was just one kitchen sink, shared by all the tenants. This was a deep concrete structure built on the outside wall of the left side of the kitchen shed and reached from the inside through an opening in that wall. There was one brass tap, and a hole at the base of the sink for the wastewater to fall directly into the concrete drain that ran out into the street gutter. Vivid green algae flourished in that drain. I would watch its long lush strands like mermaids’ hair waving in an underwater world as water from the sink rippled through.

The open-to-the-sky shower, which was everybody’s, was a simple affair of three walls of galvanised sheeting leaning against the wall of our side of the kitchen shed. One sheet, fastened to the others by hinges, swung as a door. A galvanised pipe, bent overhead, was intended as the water supply, but as water was always scarce, bathing was often simply dipping from a metal bucket the water fetched from the standpipe on Reid Lane. There, against the law, grown men, barely recognisable through the thick white suds covering them from head to toe, naked but for drawers, stood on mornings rubbing extravagant handfuls of foaminess under arms, over bodies and reaching down their hands massaging clean the unseeable bits, and, sloshing whole bucketsful over themselves, emerged clean and gleaming. As years went by, a carelessly dropped zaboca seed germinated, grew and flourished just outside the shower, giving it a shape-shifting, living roof of branches, leaves and fruit.

Our half of the kitchen and our compartment of the latrine was also used by Miss Cobus, the occupant of the bay bedroom at the front of our two rooms. That first day, she told my mother she had one child, a son, living in America. She showed us his picture – a sepia print of a young man in a military uniform. In the other half of the house, in the original living and dining rooms and the gallery, lived a family of mother, father, and three children. We didn’t see them on the first day. They had the left latrine compartment and the left side of the kitchen shed, the side with the shared sink. Also in the back, next to the latrine shed, was a guava tree that seemed to produce year round such an abundance of fruit that I could never understand why the phrase ‘guava season’ means hard times, because, daily, passers-by would call out, Neighbour, I just picking up some guava here, and a woman would come in with a basin to collect fallen fruit to be made into jam or guava cheese for home use or sale. Marmie, too, would collect fruit and make guava jelly, gifts for family and friends, rows of jars of clear red jelly, as pretty as jewels. When sunlight shone through Marmie’s guava jelly, I thought it more beautiful than a stained-glass window in church.

Our proudest furniture was Marmie’s parting gift from her disappointed mother – a handsome three-piece mahogany bedroom set. These were set up in the innermost of our two rooms, the room that had a common wall with Miss Cobus’s bay room. Taking up the most space was a massive bed where Marmie and the younger three children slept. Under the bed was storage – numerous cardboard boxes of clothes that one or other of us had outgrown and were awaiting a younger one to grow into, boxes of rags, a couple of cardboard grips, boxes of old newspapers to wrap things in – and also to be torn to size for the latrine. Also under the bed resided an enamel posie for night-time use, as we children were not allowed to venture out to the latrine in the dark.

The second furniture item was a dressing table with three deep drawers on either side where our folding clothes went, and one, longer, shallow one in the middle for our mother’s jewellery. In the space under that middle drawer there was a matching stool. A big round mirror was attached at the back, and over the drawers was a wide surface where our mother placed three embroidered, lace-edged, delicate, fine linen doilies – an oval one in the middle and a smaller round one on each side. These she alternated with ecru crocheted ones as the seasons changed from festive to ordinary. On the doilies she set a tortoiseshell backed hairbrush, a matching hand mirror and comb set, which were never used, her talcum power, her face powder and a hairbrush and comb for regular daily use.

The big matching mahogany wardrobe, the third piece, had two doors, each with brass handles and a tiny brass keyhole into which a pretty little key fitted. Inside ran a long brass rail for hanging clothes. We never had enough hangers. Hangers were of wood with a wire hook and, on these, three, sometimes four garments were hung, one over the other, so that to find a particular dress, you peeped under the skirts, peeling them apart to find the one you wanted, hoping it wasn’t too far under, because you’d have the task of lifting the others off, taking the one you wanted and putting the others back, one at a time, steupsing all the while, knowing you had to leave things just as you found them. Above the rail was a shelf, half the depth of the wardrobe, where Marmie put her hats, our church hats, her handbags, including those whose clasps were broken or straps were beyond repair, for in these she stored important documents such as birth certificates, ours and hers, rent receipts, receipts for purchases, receipts for pawned jewellery, letters, ration cards and the like. A lower shelf was for shoes. The wardrobe and dressing table drawers were lined with cedar whose fragrance hit you so powerfully right in the centre of your forehead when you opened the doors, that you only had to close your eyes to feel yourself not there at all, but somehow magicked off to an unknown, faraway, mysterious place.

There was a pair of jalousie doors between our two rooms, but these were never closed. In the second room, the one nearest the backyard, there was a wire-mesh-sided food safe, a canvas folding cot where we sat, if we ever needed to sit indoors during the day, and where I, as the privileged eldest child, slept at night. In this back room, too, stood Marmie’s precious foot-pedal Singer sewing machine, an oilcloth-covered wooden table and two wooden chairs. The partition walls between the rooms, our two and those of the neighbours in the adjoining rooms, were made of upright wood planks. These walls didn’t quite reach the ceiling. Slender, regularly spaced square-section wooden rods bridged the wide gap. Lower down, halfway along the walls ran a narrow ledge, very useful as a shelf for small objects, a bar of Palmolive soap for bathing, a bar of yellow Sunlight soap for washing clothes, a tin opener, a small flat round tin of Vicks vapour rub, a small tub of Vaseline, boxes of matches, safety pins and hair pins.

In each room there was a pair of jalousie windows that could be flung open and these were flanked by jalousies that could be pushed to close and held in place by a long pin that fitted into a hole in the frame. I spent many a happy childhood hour opening and closing jalousies, seeing how they all moved together, working out the way the parts fitted together, astonished at the clever, simple closing mechanism. The houses on Pelham Street were so close together that whenever I was idly singing, Mr Bones, the father of the Portuguese family in the next-door house, would call out and ask me to sing the Ave Maria for him, and after I’d sung it he’d want to hear it again. Our one door, the one that opened to the back yard, was split in two across the middle, a stable door I learned later. It was kept fully open when any of us was at home. At night, we slid a bolt into place on the inside of each half and when we went out, we slid shut the one bolt on the outside. Why only one bolt, I wondered. I examined the door, opening and closing it, marvelling at the ingenuity of the simple and effective design that made this possible.

Marmie cooked our meals in the kitchen shed on a two-burner pitch-oil stove placed at one end of a long narrow table. On the rest of space, she stacked an iron stewing pot, one big metal boiling pot with a lid, two big bowls, one metal pot spoon, a sharp knife, and our plates, cups, deep soup plates with rims and an odd assortment of spoons, knives and forks.

After a few years, when Miss Cobus moved out to join her son in America, we got her room, and when the other people moved out sometime after, we were able to occupy the whole house. Perhaps that’s when Pappy bought the house from Mr Sarvary. I must have been in my midteens at the time. I don’t think any of us children had any sense of either being tenants or becoming a family of homeowners when the change happened. Pappy didn’t live with us but he was the person in charge and as he was always secretive about his real life and his dealings, I never knew whether he’d bought it outright with cash or had taken out a loan, whether he bought it when the other tenants left or whether his buying it occasioned their leaving. I wonder now whether Marmie knew any more than I. Whatever had been the cause, we simply spread as new space was opened up to us. Miss Cobus’s bay room became Marmie’s bedroom and her bed moved in there. Another bed was purchased or made for the room she’d vacated, and when we got the other half of the house, it slowly reverted to its original functional design as living room, dining room and gallery for cooling off, looking at the street and chatting with passers-by, with a bannister for Marmie’s little clay pots of African violets and ivy. Along each side of the red steps leading to the front door, she put large sweet-oil tins, painted green, and grew tall, yellow-stem palms.

Marmie sent a message to Sidney a cabinetmaker from up the Valley Road. They talked a bit and he went away. At the time she was working six days a week as a cashier in a Chinese grocery in Charlotte Street, for nine dollars a week; from this she put one dollar a week in a sou-sou. She took the first hand so that Sidney could buy the wood and start to build the furniture – a mahogany, curved-arms morris chair set, an oval dining table and harp-back chairs. These would bring the drawing room and dining room to life. After that sou-sou cycle had finished and a new one started, she once again took a first hand to pay Sidney for his workmanship. Sacks of ticking stuffed with coconut fibre and beaten into shape with a long hooked bois became seat cushions. These and stylish floral cretonne cushion covers and lace curtains for the long French doors came with the rhythm of the sou-sou cycle.

We children took it all in our stride, this flowing into new space and having new things. But while I hadn’t felt particularly deprived before, I did feel a lift in moving up in the world, but there was no way I could match Marmie’s joy and satisfaction in her huge accomplishment. For Marmie, who had fallen further and further from grace with her family with the arrival of each of the four of us, and the increasing diminishment of her circumstances as her burdens grew, this was a big step. Marmie, at last, had a home she could be proud of. She worked hard over the years to keep up to this standard; she made improvements to the kitchen, maintained the yard and created a pretty garden at the front.

And to think that Pappy had decided to sell her home while she was away, working as a domestic and nanny in Brooklyn, an illegal alien there, unable to come home and fend for herself. How could she come back? She would be denied re-entry to the land of opportunity if she left. And to think that Pappy had waited for me to come back home to break this news to me, not in person, but manipulatively through Marmie’s sister’s husband. And to think he was expecting me to give him my blessing – which I did – with the promise, relayed through the intermediary uncle-in-law, that he would give her half of the twenty-eight thousand Trinidad and Tobago dollars that he got for it – a promise he didn’t keep, because he said he’d used it up by the time she was able to return home to fix up her papers to go back up north, no longer an illegal alien but a green card holder.

About a dozen or so years ago, I started going back to Belmont. I would always take the same route. Turn left off the Savannah after the Queen’s Hall roundabout on to Belmont Circular Road, passing the new police station on the rising slope to the left, the Belmont Secondary School, on the spot where the Catholic Youth Organisation once stood, past the grand old family homes, now subdivided into boutique studios and offices, and Providence Girls’ School, once just a single grand and charming traditional gingerbread building, scrupulously maintained, now with the addition up the slope of a cluster of new charmless sprawling concrete buildings. Then I’d take the next right down into Pelham Street, turning second right onto Clifford Street, to my destination, the home of a childhood friend, with whom I’d recently reconnected.

But before I got there, driving along Pelham Street, I’d slow down a short way before the junction with Reid Lane so as to be at a steady crawl when passing number 74. From the street side I could see that the house had undergone some changes, had been modernised. The gallery was now enclosed, with burglar proofing wherever there was an opening to the outside. But the shape of the house, the steep pitched roof, with its white finial topping the crest at the front and back – like the twin exclamation marks that bracket statements of surprise and outbursts in Spanish – the fretwork fringed porte cochère, the bay bedroom, the twisted-wire fence above a low solid wall, the way the house sat and presented itself to the world, was instantly, heart-clutchingly, indisputably, home.

There was never anyone about and the windows and doors seemed to be always closed, so I wondered whether anyone lived there, though I could see it wasn’t abandoned; everything looked too tidy, too well kept for that. Perhaps, I thought, they were there, indoors, sealed off in the comfort of air-conditioning – for who is out and about on the road on a weekday in the middle of the hot morning?

But one day there was someone. A man. His back towards the road, he was concentrating on sweeping the drain outside the house. I braked and wound down the passenger-side window. Morning. Excuse me, I said. Is this your house? He paused in his sweeping, stooped to brush whatever he’d gathered into a scoop, pulled himself up along the broom handle, leaned against the broom steadying himself, before he turned to face the car. I felt I could read him sizing me up. Old white car, clearly a roll-on-roll-off, grey-haired woman maybe ten years older than himself, brown like himself, she wearing a tatty T-shirt and unfashionably un-ripped jeans, so perhaps not an estate agent, or insurance salesperson, or developer, or lawyer or anyone of that predatory ilk who, trolling through such neighbourhoods, buy up old property from the vulnerable elderly, to tear down and put up blocks of apartments.

So, not suspicious but puzzled, he took his time to gather his thoughts, the Corolla engine purring softly along with him, before he answered. It belongs to my brother. He’s away. I’m staying here. I could sense an unasked question, Why do you want to know? And I offered, I used to live here once, dramatizing, by borrowing a Jean Rhys’ story title, to cover my suddenly felt embarrassment at intruding on an old man on a Saturday morning and making him reveal to a total stranger his relationship with a house and his status as someone dependant on a foreign-based sibling for somewhere to live and his exposing his gratitude for this privilege by keeping the place and its surroundings nice. I felt the need to say more, to make up for my flippant explanation of my curiosity. I grew up here, I said. I see your brother made some changes. It’s different. But it’s still nice. He nodded as if he understood what the house would mean to me even after all this time. I wanted him to say, Would you like to come in? Would you like to see inside? To see what is different? But he didn’t and I understood that the conversation had nowhere else to go. I said, Thank you. Have a good day. As if he was a customer and I a Hi Lo cashier.

I think often about that encounter and how I could have made it go differently. Should I have asked to be shown around? How would he have received such a request? Supposing he had a wife or significant other there who would have wondered at his bringing a woman, a stranger, into their home? And what sort of woman would ask a strange man to take her into his home? What would his neighbours think of him? What if he’d refused!

I don’t go to Belmont much anymore. Not since my childhood friend died. The picture of 74 Pelham Street in my head shape-shifts between my seared knowledge of it from my childhood and my more recent brushing acquaintance with it, depending on whether my thoughts are in the then or in the now. As is the case with my thoughts on anything and everything, I guess.

Except that, more recently, long years after I had last gone past the house, John Robert Lee, a St Lucian writer whom I knew only by reputation and through his literary email newsletter, but had finally met in person at Carifesta in Port of Spain a couple months earlier, sent me an email.

Am sending you, on impulse, some recent poems coming out of my recent stay in Belmont. All inspired by my own photos taken as I walked to and from the savannah.

I didn’t know he’d stayed in Belmont and I don’t think that he knew that I was from there, so I was curious to see what of my old stomping ground had caught his attention and inspired poems. Before reading the poems, I flipped through the attached photos and when I got to a particular one, my breath caught in my throat. There among them was 74 Pelham Street. The poet had been staying at a newish guesthouse built on the site of the Chinese grocery of my childhood. The photo, taken from his second floor bedroom window opposite my old home, showed the house almost exactly as I’d last seen it, except that the porte cochère had vanished and the perimeter wall had been raised, swallowing the space where the green twisted-wire fence once allowed passers-by views into the front garden and the golden startle of Marmie’s chrysanthemums.

PHOTOGRAPHS

Chuichi Nagumo, born 25 March 1887, Vice Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy, lifts binoculars to his eyes. A wintry sun rising over the Pacific horizon casts a feeble shaft of light on to the rail of the aircraft carrier. Six aircraft carriers, forty torpedo planes, forty-three fighters, forty-nine high-level bombers and fifty-one dive-bombers are assembled, primed and poised, awaiting his signal.

Seven thousand miles away in Upper Belmont Valley Road, Yvonne Lafond, born 25 March 1917, is sitting on a low bench by the water cistern. She places a basin under the tap and lifts the lever to let the water flow on to the last batch of new muslin diapers, flannel belly bands and tiny pastel cotton chemises she’s sewn and embroidered herself. The noonday sun spins out a blinding dazzle from the twisting stream of water and, as she looks down into the basin at the rising water level, bright pinpoints of swirling constellations pull her into their spinning. She grips the edge of the basin. Steadying herself, she leans over, tips the water away, gathers the little clothes in both hands and squeezes them into a ball. She must hang the little things on the clothesline. She makes to get up, but can’t. Every muscle in her body is tensed against the pain that holds her belly in its iron grip.

In the early afternoon of Thursday 4th December 1941, on her mother’s bed in her grandmother’s house in Upper Belmont Valley Road, Belmont, Trinidad, a baby girl is born.

Her first cry startles two mockingbirds feasting on clusters of fragrant fruit hanging from the tree outside the bedroom window. As they lift off, the rebounding branch disrupts the air, deflects a morpho’s smooth glide into a frenzied flutter of iridescent blue, sends a curl of aromatic air through the canopy of leaves to be caught in a rising thermal and transported in the trades across the Gulf of Paria into the Caribbean sea, through the Panama canal and onward to the Pacific, where three days into its journey the tang of chenettes tickles the nostrils of the Vice-Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy. At that moment he orders three-hundred and fifty-three Imperial Japanese aircraft to a surprise rendezvous with the American naval base at Pearl Harbour. On Monday 8 December 1941, Trinidad declares war on Japan. Britain and the United States of America do too. With Europe already consuming itself with rage, North America and Asia are drawn into further embroilment.

The mother and the baby girl drift in and out of sleep on their first day as two, wrapped together as if still one, snatches of radio broadcasting from London in another room flowing through the ear of one and reverberating in the head of the other. A village in wartime… is innocence enough… parents’ messages to evacuee children in Canada… Calling the West Indies… Christmas greetings from London from two young Trinidadian airmen, Mr Mervyn Cipriani and Mr Ulric Cross, invited by Miss Una Marson. Hardly in the world, yet the world is already pressing the newborn with the urgency of its preoccupations. The whole world is at war. And so are the baby girl’s mother and her mother. The new mother is twenty-four when the girl is born. Not young, at least not too young to be a mother. Already her twin sister is the mother of four, another sister of two; a third is expecting her first. All younger, all married.

Did she feel left behind, left on the shelf, I wonder. Was that why she, unmarried, had me for a man whose name I did not know until I was fifty, when she, on her deathbed, unable to speak – her larynx and much else surgically gone – at my asking at this last minute, wrote the name of the man who had planted his seed in her, rousing her waiting egg to acceptance, to become me. On that day, almost the last day of her almost seventy-five years, she wrote his name with care on a child’s magic erasing slate and, on my reading it, she lifted the clear plastic sheet so she could write more, and that brisk parting of the sheets took his name away, and he was once again gone, swiftly erased. Overlying him was an explanation, an elaboration: that they were in love, they were to be married, that his parents had whisked him off abroad to study, to prevent him being tied down with wife and family. All this she wrote, her scribble wilder and wilder, lines sloping off the plastic page that she lifted and lifted again. And I, there, was looking under each page, trying to get back to where he was, where he’d gone, buried under newer words, overlain by newer stories. I often wonder whether the implantation of half of me was as swift, as casual, as my fleeting sight of the reality of him, a name on that magic slate.

My mother was born in the same house where I was born. I like to imagine it was the same bed, so that I can claim the full weight of the biblical issue of blood connection with my grandmother. She, though disappointed about the shame the news and views of the impending arrival brought upon the family, once I was no longer the visible bulging evidence of her daughter’s downfall, but a separate, guiltless person, my grandmother loved me.

Growing up in my grandmother’s house I saw my grandmother as an old woman – but how could that be? She couldn’t have been more than fifty, and now I’d give my eyeteeth to be back there, back at fifty, fifty years young – but what the child me saw as old were threads of steel-grey woven through that single thick dark plait hanging down the exact middle of her straight back, her daily siestas in the darkened bedroom with only the shrill scraping of cicadas for company, a stifling torpor seeping from under the closed door, invading the whole house where we all fight against yet must succumb to sleep, too, as if in a fairytale castle. Above all, in my eyes, my grandmother’s advanced age lay in her unquestioned authority over everyone – her still-at-home sons, the visiting grandchildren, the household workers and the tenants on the land. Even her adult daughters living elsewhere, with husbands at home to answer to, children of their own to answer to them, reverted to a childlike helpless state in her presence. But she must have been young once, and there is a story of her early life.

From what my mother told my youngest daughter, her mother was born in Venezuela to parents who were on the wrong side of one of the many civil upheavals in that land during the eighteen hundreds. As descendants of the original people of the land fighting for what was then called native rights – the word indigenous, with the authority of being as much an inalienable part of the landscape as the trees and rivers and soil, was not yet a label of indisputable rights – my grandmother’s parents were both killed. My orphaned grandmother, their daughter, and I do not know if only child, was smuggled out of the country and secreted away to be adopted and raised in another family.

When she was about twelve, my daughter, while interviewing my mother, taped that story. In the process of some minor personal upheaval many years after, I, mea culpa, must have thrown away that cassette tape, which I had never heard, and was the only record of my mother’s voice speaking about a critical part of her immediate ancestors’ life. The tape lay jumbled among unidentifiable and indistinguishable tapes of calypso, parang, the Supremes and Grease, and when I committed that unpardonable error, cassettes were obsolete, and I was fighting a lost battle with a plague of termites that had tunnelled and granulated whole wardrobes and chests of drawers. So, at that time, my watchwords were to throw out, discard, minimize; now I know examine, select, preserve would have been a more judicious motto. Here I am with enough time on my hands and the interest to be able to take an unlimited numbers of cassette tapes to a specialist and have them put on CDs, or a memory stick, or what ever is the latest thing, and listen to the recordings at leisure. But no. Dear Carys, I am truly sorry that I did not treat your initiative with the respect it deserved. I have deprived us all of a proper ancestral story.

What else does my daughter recall of that interview? That her great grandmother had grown up in one of the islands to the north, St Kitts, maybe, and was adopted by an English family involved in colonial administration, and that it was at an event after their new posting to Port of Spain that a young Frenchman, a court interpreter, her future husband, was presented to her, my young grandmother-to-be. Given the privileged circumstances of her upbringing, somewhere there must be old family albums, and among yellowing black and white and faded sepia photos, a darker skinned presence, a Dido Belle among the pale Anglo-Saxons whose descendants now perhaps gaze in puzzlement at her image. The only picture I have of her is a copy of a much later photo in an aunt’s family album.

It is a formal family photo taken outdoors, perhaps in the front yard of their Belmont home. My grandmother dominates the photo. She is sitting upright, hands folded in her lap; her hair, cut to just below her earlobes, frames a strong, determined face. It is the face I see on every portrait of a warrior Taino, Aruac, Warrao, Kalinago, who inhabited these islands in the millennia before the cataclysm of 1492. It is a deal with me if you dare kind of face. Both her feet are firmly planted on the ground, as if she’d stamped them there to assert her right to that space. Even seated, she is a head above the man in the chair next to hers. He is slouched in that careless louche way of those white men of that time who were not descendants of land-granted cedulites, not of that proud entitled aristocracy, not formerly owners of chattled human beings. He is sitting with the kind of pulling in, the trying to minimise themselves, that men like him seemed to adopt when photographed with their family. That slightly-built, pale Frenchman, my grandmother’s husband, the grandfather whom I never knew, had disembarked in the Port of Spain harbour when a ship from Marseille had anchored offshore, awaiting bunkering on its way to Brazil. Then he – ship’s boy or runaway, independent child immigrant or transported, indentured minor, aged thirteen or fourteen or fifteen – was taken or captured or adopted at the docks by a securely settled Portuguese merchant whose family name, Pestana, and confident profile are memorialised on an oval bas-relief complete with laurel wreath on the back wall of the family plot in Lapeyrouse Cemetery Port of Spain, where he, my grandfather, was to be buried some forty something years later. Also seated in the photo is another man who is discernably half Chinese, round-faced, mixed with African and something else. He is Moon, my mother’s twin sister’s husband.

Standing behind and flanking this front row are the Lafond children, very pale and at first glance seeming somewhat uncertain. My Uncle Carmie, the eldest, the only boy in long trousers, stands slightly aside, observing the others, as if already aware that responsibility for their wellbeing would fall on his shoulders, and he’s trying to discern which of them he’ll have to take care of. The other boys, Tebeau and Véné are in formal knee-length trousers. Véné, hands in pockets, the artist-to-be, carries off an air of insouciance. Tebeau is a boy. That’s all. A boy-boy. Maybe thinking of the game of marbles he’s been called from to get bathed and dressed for this formal family photograph. There are four girls. The twins, my mother Yvonne and her sister Yvette, can be distinguished apart only because Yvette is holding a baby, my eldest cousin, Lenfar. Yvonne and Yvette, probably just eighteen, sport flapper hairstyles, shoes and dresses, as if ready to go to a dance and are looking forward to doing the Charleston. Nissa is there, in plaits and big floppy hair-ribbon bows, looking down and away, not looking at the camera. And there’s Fiette, the baby of the family, holding a doll and standing in that belly-thrusting-forward way of little children. These are the names I know them by, and not a one is the name on their birth certificates.

When I was ten, my mother handed me an envelope to take to school to present for registration for the College Exhibition Examination. I opened the envelope before handing it to my teacher and that’s how I saw my birth certificate for the first time. I read the first column. Child’s Name: Barbara Magdalen. Next column, Mother’s Name: Thalitha. I stop reading. My mother is Yvonne. Who is this Thalitha? I am the eldest child of Yvonne Lafond. Am I who I think I am? Does Thalitha know that someone called Yvonne has me and says she is my mother? Maybe this Thalitha person was a friend of my moth… a friend of Yvonne’s and Thalitha got sick, very sick, and she left me with Yvonne before she died. That’s to prevent me being sent to the orphan home. When I peep through the gap where the galvanised fence around the orphanage has pulled away, I see the orphans running around the yard. They wear a uniform even if it isn’t school time. Rita, who lives on Belle Eau Road near the orphanage, says that’s so people can recognise them if they try to run away. Rita says that sometimes ladies get very sick when they are having a baby and if they die the baby is put into the orphanage. I wonder whether Thalitha died while she was having me.

I slipped the paper back in the envelope so no one else could see it. When Mrs Thornhill called for the birth certificates I handed mine in like everyone else. I sat there in class all morning, but it was as if I wasn’t there, yet at the same time not aware of being anywhere else, as if I was asleep not dreaming, with eyes wide open. And then, as I began to notice where I was and what was going on, I started to try to work out the puzzle of the names and eventually I decided that maybe Thalitha was another of my mother’s names, just as I had two, a first name and a middle name, and that for some reason she chose not to put Yvonne on my birth certificate. I had never heard anyone call her Thalitha. She was always Yvonne. What strikes me now as particularly sad about how I felt at that time, what I went through that long confused morning, is that when I got home, still thinking, still trying to agree in my head with what I had worked out was the reason for my mother’s different name, I put away the envelope with my birth certificate in the old grey handbag in the wardrobe where Marmie kept precious papers, and when Marmie got home from work that night I did not ask her about it.

One by one as they died, my mother’s siblings’ true names were revealed on their funeral programmes. It was as if at death they were born again to their intended identity, that their life here with those other names was just a temporary sojourn. I tried to imagine what different life reclusive sibilant Nissa might have lived if she had been called instead by her definitive, explosive Merle. Or Tebeau – ‘Ti Beau, handsome little one’ – if he’d worn his more macho Leon name, would he have been bolder, more selfassured? And Fiette – Fillette, little girl, indulged to the last – who would she have been as Nyce? Or maybe that’s not so different. I certainly believe that had my mother been called Thalitha – all three syllables of it with that repeated th sound which demands care and attention in its articulation, tongue between the front teeth twice in one eight-letter word, the openmouth for the ah sound also twice, the stretched lips for lee – she would have been treated with more respect and my birth certificate would not have read Father’s Name: Illegitimate.

Auntie Nissa named me Barbara because she was a fan of the movie star, Barbara Stanwyck, and considering the shameful circumstances of my conception, perhaps nobody else cared enough to bother to suggest an alternative. Marmie and all the family always called me Babs; my children, Babsies. I get Barb, Barbie, from friends, but mostly it’s Barbara. But Auntie Nissa must have been doubly inspired. When I was fourteen or so I visited a friend who had the Catholic calendar, a big paper poster, pinned up just inside her front door and, as the dates of many feasts depend on the moon, they change every year (Easter, Good Friday, Corpus Christi, Pentecost and so on), so you need to buy a new calendar every year to know when those important feast days fall. Such a calendar was not an item in which Marmie could invest a whole shilling. So while waiting for my friend, I idly glanced down the list of three hundred and sixty-five feast days and saints’ days. When my eyes landed on my birthday, they couldn’t believe what they were reading. It turns out that my birthday is the feast of St Barbara, virgin, martyr. It is a fixed feast day, every year, same date. I felt marked, singled out in some way and not in an altogether nice way either. More like an invisible mark on my forehead. I don’t know whether she’s still venerated, St Barbara, that is. The Catholic church purged dozens of dubious characters from its list of saints after I left it, and I haven’t checked on her fate since. I wouldn’t be surprised to discover that there was a double purge – of both my eponymous saint and me. I’ve never told anybody that coincidence of my name, for who would find it as full of foreboding as I did? I don’t know what criteria my Lafond grandparents used to name their large family; I don’t think any of their names are of those of saints.

Papa and Maman – Puppah and Mummah to their children – my grandmother was Frances, my grandfather, Eugene. He was a linguist, speaking and interpreting French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and English. Could he have been a ship’s boy for many years and picked up in the quick easy way that children do the many languages of crew and passengers before that final fateful disembarking. With this facility he worked in the Trinidad courts interpreting back and forth for the polyglot inhabitants and transients of this Babel of a British colony who brought their matters, or had their matters brought, to His Majesty’s Courthouse at the end of the 1890s and the early 1900s. This is in the known record of my grandfather’s life. It is said he later added a smattering of Hindi and Bhojpuri, but not for use in an official capacity. His other vocation was the garden. He was an ardent horticulturist.

On land in Upper Belmont Valley Road, he set out to create a new Eden, carving out a space on the riverbank and on the forested slopes of that cool tightly bound valley to cultivate, not food for his growing family, but prize hybrid roses, gladioli, dahlias and carnations from cuttings, slips, bulbs, corms and tubers imported from Holland, as it was then called, ordered by handwritten letter in English with a postal order in pounds sterling, and brought in the holds of ships tenderly packaged in paper and corrugated cardboard. This last I learned from my Uncle Carmie, who along with my mother inherited the gardening gene. Uncle Carmie himself continued to grow temperate flowers in a tropical land to the day he died.

I like to imagine my grandfather in the soft afternoon sunshine in that quiet garden. He is wearing a straw hat and walking among the flowerbeds, removing excess side shoots from roses to encourage air circulation and sturdy upward growth; banking up at its base a top-heavy gladioli, its spike a row of fat buds about to burst open; dead-heading dahlias past their best to encourage the new buds to open. Or at night, in the flickering flame of a pitch-oil lamp, head bent over the latest illustrated catalogues that had been left at the post office in town for his collection, poring over the pictures, descriptions and prices of the newest species and hybrids to choose for his expanding garden. It is only there and in the courthouse that I can see him as autonomous, in charge, and fully himself. Not the awkward displaced person I see in that single snapshot story, slumped in his chair, his native-blood wife towering over him.

Widowed young, with a large brood of barely educated dependants, children and household help alike, and no visible means of support, what could Frances Lafond, my grandmother, do? This much I know from my own childhood. The boys continued the garden, but whereas their Puppah grew flowers for the joy of it, for the showing and sharing of them, they tried to turn the garden into a commercial venture, cycling into town early every morning with handle-baskets full of freshly cut flowers in bud to deliver to the two flower shops there, but the few cents for a perfect bloom didn’t multiply up to enough to keep everyone afloat, and I suspect that as young boys with other interests they didn’t have the passion for flowers that their Puppah had. My grandmother was therefore forced to make hard decisions.

She had three unmarried sons and three spinster daughters at home when her husband died and his monthly salary came to an end. She had the house they lived in, a grand red concrete structure up on the hill and reached on foot by a narrow dirt track. There was electricity supplied by a kerosene-fired Delco generator and spring-fed, year-round running water stored in a large concrete cistern. She had support staff to feed, house and pay – a cook, a washerwoman, a yardman and a general maid – for who else was there to clean the cistern, remake the path in the dry season, clear the aggressive bush around the house, peel and cook and pound ground provision for food, scale the fish, kill the hog and salt it in wooden barrels, feed, fatten, kill, pluck, season and cook the chickens, mend the broken plumbing, clean the gutters, clear away the fallen fruit that littered the yard, wash, starch and iron the clothes, polish the furniture and floors, and sweep mop and cobweb the house?