Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IVP Formatio

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

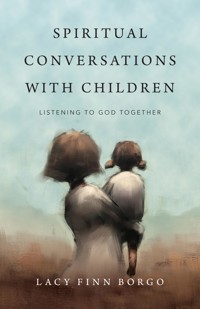

We are born into this world with a natural longing to connect to God and other human beings. When children have a listening companion who hears, acknowledges, and encourages their early experiences with God, it creates a spiritual footprint that shapes their lives. How can we increase our capacity to engage children in spiritual conversations? In this book Lacy Finn Borgo draws on her own experience of practicing spiritual direction with children. She offers an overview of childhood spiritual formation and introduces key skills for engaging conversation—posture, power, and patterns—from a Christ-centered perspective. "When we are fully present and open to another, we will be changed," Borgo writes. "Indeed, as you listen to God with a child, the child will lead you into a fuller experience of God's love and acceptance." In this book you'll find: - Sample interactive dialogues with children - Ideas for engaging children with play, art, and movement - Prayers to use together Whether you are a parent or grandparent, pastor or spiritual director, you will find this to be a friendly guide into deeper ways of listening.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 217

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SPIRITUAL CONVERSATIONS WITH CHILDREN

LISTENING TO GOD TOGETHER

For the children at Haven House

CONTENTS

Learning from Christopher

Reality [is] what you run into when you are wrong.

DALLAS WILLARD

ARMED WITH A MASTER’S DEGREE in education and accolades for leading educational workshops for the New York State Teacher’s Union, I had no reason to question my firmly held knowledge on the growth and development of children. In my very young mind and heart I thought I knew all there was to know about childhood. Reality, a gift of grace, came knocking when Christopher walked into my fourth-grade classroom.1 It was only week two of the school year and he had already been shuffled from classroom to classroom and suspended from school altogether. I was the third and last fourth-grade teacher to welcome him into her classroom. One more incident and he would have to go to the alternative school for children with behavioral disorders.

Christopher was a smart kid, using whatever power he possessed for his survival. In my classroom the situation was no different. Within the first week he jumped out of the second-story window and shimmied down the fire escape to avoid a math test. Strangely enough, the break for both Christopher and me came when he was suspended from the cafeteria. His disruptive behavior had become an overwhelming obstacle for getting lunch served to eight hundred children. The lunch staff had no choice but to ban him from the cafeteria.

I had run into reality. I had no more knowledge to draw upon and the system had run out of beneficial options. In the beginning it was simply a matter of location. Christopher could not be in the cafeteria, so he ate lunch with me in our classroom. As lunch was my only break of the day, I had no desire to teach, lecture, or even change him. Over the course of our seven months of lunches, however, I began to become curious. Christopher talked all through our lunches. He would recount bits of his days or tell me stories about his family. Sometimes he would reflect on the deeper things in his life, like how he felt about his mother leaving, why he thought death was so scary, and the unbelievable kindness of our vice principal, Mr. Bell. I began to wonder what was going on inside of Christopher. Christopher had astonishing hope in the future and in the goodness of people; he possessed a mystery that I could not define or control.

As a Christ-follower I wondered what ways God was reaching for Christopher in all the mess. To preserve the public school separation of religious talk from academics, I began to ask Christopher about goodness rather than about God. What did goodness look like to him? When did something good happen to him? What was it like to experience goodness? At the time I knew little about the three great transcendental ideas: goodness, truth, and beauty. However, I knew that God was good and where goodness was, God was there too.

Inspired by my curious inquiry, Christopher opened up his inner world to me. There was more to Christopher than what was presented in his behavior, more going on in him than the school counselors could deduce. During our lunches I gave him no lectures, I taught him nothing. In fact, I spoke very little besides asking a few questions. Christopher made it through the fourth grade and even the fifth. He went off to middle school, but sometimes he would return to my classroom and hang around after class, longing to be listened to.2

Christopher taught me how to listen. My time with him started a nearly thirty-year exploration into understanding the spiritual lives of children. This journey has yielded new insights, fresh understanding, deep empathy, and, most surprisingly, healing for my own childhood wounds. It is my hope that you will gain some of the treasures I have. This book presents what doctoral research and experience have taught me about having spiritual conversations with children. I began listening to God with children in 2014 at Haven House. Haven House is a transitional facility for homeless families. It is dorm-style living for homeless families that includes a two-year program designed to help move them into sustainable independence. I meet with children one-on-one as a spiritual companion to them. We call it “holy listening,” taken from Margaret Guenther’s book on spiritual direction.

In this book we will explore how spiritual conversations with children support their life with God. We will learn not only what makes these conversations unique but also how to have them. We will begin by learning from Jesus. Jesus had a hospitable and welcoming posture toward children. We will uncover the role of longing, belonging, and connection in a child’s life with God. Diving into spiritual formation with children as a guide for spiritual growth, we will think deeply about the four elements of children’s spiritual formation and the implications for children and the adults who long to accompany them. We will take a look at three Ps—posture, power, and patterns—and how each of these shape spiritual conversations with children. We will notice the natural power dynamic between adults and children and how Jesus used his body to empower and honor children.

Pushing against our natural inclination to talk at or teach children, we will learn how our eyes and ears help us to contemplatively listen to children, and further how this listening opens a child to respond to God’s invitation. We will learn from children how play and projection help them to experience God and reflect upon their life in light of that experience. As we become more fluent in play and projection, we will learn how to help children recognize the Spirit’s movement in their life and respond to this movement in a way that is unique to their natural inclinations.

Finally, we will rest in mystery. The human relationship with divine love is to be lived not dissected. Our grasp of the workings of this relationship is at best a generous guide; at worst it is a mechanized jail cell. When we accompany a child on their journey with God, we do so from the position of knowing only in part. We hold this pearl of great price and marvel with wonder at its beauty.

Learning to be a listening adult to children yields enduring benefits. When children have a listening companion who hears, acknowledges, and encourages their early experiences with God, it creates a spiritual footprint that will shape the way a child engages with God, others, and themselves. Spiritual conversations with children foster resiliency in the life of the child. Children who have learned to listen to their inner life and orient that life in divine community have a calibrated inner compass that can guide them when the storms of life inevitably come.

Parents are essential listening companions, and children need additional adults who are present to listen and to encourage them in their life with God. A child’s life with God suffers spiritual anemia when there is a lack of community. You can be one of the listening adults who supports a child’s spiritual life.

Spiritual conversation with children also benefits the adult doing the listening. When we are fully present and open to another, we will be changed. Our own childhood self will be offered the invitation to connect with God. The Spirit longs to heal old wounds and to embrace long-buried gifts. Indeed, as you listen to God with a child, the child will lead you into a fuller experience of God’s love and acceptance.

If you are a parent or grandparent, this book is for you. Listening to a child’s journey with God is a sacred gift we can give them. Family is the most deeply formational social context we will ever live in. If you are a pastor, friend, or teacher of children, this book is for you. To accompany children in their life with God has the potential to shape the classroom, the congregation, and the world. If you are a spiritual director, this book is for you. It is my hope that it will offer a few guides and a heap of courage for you to begin to host listening spaces for children. These young beloveds of God are participants in the present and future; to invest in them is to witness the unfolding of grace.

Learning from Jesus

Let the little children come to me; do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs. Truly I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.

JESUS

ILIVE ON A SMALL HOBBY FARM in Western Colorado. We have horses, chickens, dogs, cats, and goats. After twelve years of keeping company with goats, I’ve learned a thing or two. For example, I have learned that if a fence won’t hold water it won’t hold a goat. I have learned that horses, dogs, and goats can read human body language and will use this superpower in the service of their belly.

After a few years into our little goat adventure, I also learned that when a mama goat is getting ready to have her kids, she prepares. “Kids” are baby goats, and as I have children of my own, the similarities are not lost on me. The mama goat will paw the ground like she’s making a nest. We might see her rub her abdomen against a tree to move the kid into place, she might even stretch, doing a funny sort of goat yoga, downward dog meets cat pose, to move her young near the birth canal. One particular spring, about ten years ago, I noticed that mama goats do one other remarkable thing.

At that time I was in a raw and honest place in my walk with God. I was wondering if God truly loved human beings. Questions circled the inner landscape of my life. Did God really want us, long for us? Did the character of God’s relationship with human beings consist of love and longing? Or was it more like duty and drudgery? My shaky reasoning went something like this: God created us, but we ended up being such a mess that God, out of his own integrity, had to deal with us. But in all honesty, God didn’t want to, he just wanted to nuke the planet and be done with us.

In the midst of this conversation spring had sprung, and I was out in a tiny lean-to shed with a mama goat who was getting ready to kid. For several days she had been making her nest, pawing the ground, moving dirt and hay around in circles. I often found her rubbing her body against a tree, urging her young into the birth canal. It was just her and me on a chilly spring night, and I could tell that her time had come. All the usual signs were there. I remember that the sky was crystal clear, I could see my breath and hers. The only light was from a headlamp I was wearing, and after several dirty looks from her, I turned it off. Who knew goats can give the stink eye?

About twenty minutes before the baby was born, she began to do one thing that would forever change how I understood God’s love and longing. She began to hum or sing or something like it. A soft bleat with her lips closed. It wasn’t like a cry as if she was in pain, it was soft and soothing. She continued this “singing” through the contractions, through the pushing, and when, finally, the baby was born, she nuzzled the new life. She licked it clean and continued to sing until the new life sang back.

For the next few hours, as my legs went numb from sitting on a paint can, mama and baby softly, in a very tender way, sang to one another. In this way she marked her baby as hers and the baby knew its mama’s voice and sang back. Connection was in the singing. Safety was in the song. God used that moment to speak deep healing and truth into my questions. Our conversation took a monumental shift.

LONGING FOR CONNECTION

Developmental psychologists tell us that every human comes into the world looking, reaching, and longing for connection. They tell us that even within the womb children connect with their mother’s voice, their mother’s smell, and their mother’s heartbeat. After we are born, we search our parents’ eyes for connection. When they smile, we smile back. This first smile doesn’t mean the same for the babies as it does for the smitten parents: the babies are not pleased or happy; they are mirroring the parents in an effort to connect.1

Although this intense desire to connect is an attempt for physical survival, it is also a part of our psychological and spiritual survival. The child who doesn’t connect with a primary caregiver by the age of two is likely to develop something called reactive attachment disorder, which is a serious and horribly painful condition in which a person has the longing to connect but is unable.

This longing to connect is woven into every human person. From our first breath we are governed by this longing. My first memorable example of early human longing was when my daughter was born. As soon as she was placed in my husband’s outstretched arms, she grabbed onto his finger, which is a Palmer Grasp reflex, I am told. The intense longing to connect is even wired into our reflexes.

But not only are humans wired for longing, we were created from longing. The Creator God longed us into existence. “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you,” says Jeremiah 1:5. The psalmist reminds us, “It was you who formed my inward parts; you knit me together in my mother’s womb” (Psalm 139:13). And Paul explains that God “chose us in [Christ] before the creation of the world” (Ephesians 1:4 NIV).

Every human has been chosen. God, who needed nothing else to be whole and whose joy was complete before one ounce of creation, longed for you. We human beings often long from a place of brokenness, but God, who is whole and holy, longs from a place of abundance and joy. The parable of the lost sheep found in Matthew 18:10-14 is about longing. It is a story about a shepherd who longs for his sheep so intensely that he leaves the ninety-nine to find the lost one. God has been longing for you, longing to connect with you, since before your very beginning. Every child you know has been longed by God into existence.

We also long for God. Just as we are hardwired to seek connection with our caregivers, we are hardwired to seek connection with God. Lisa Miller, psychology and education professor at Columbia, says, “Biologically, we are hardwired for spiritual connection. Spiritual development is for our species a biological and psychological imperative from birth.”2 This hardwiring pulses in our bodies, in our minds and hearts, compelling us to reach for connection with God.

We get a glimpse of the human wiring to connect in Mark 10:13-16.

People were bringing little children to him in order that he might touch them; and the disciples spoke sternly to them. But when Jesus saw this, he was indignant and said to them, “Let the little children come to me; do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the kingdom of God belongs. Truly I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will never enter it.” And he took them up in his arms, laid his hands on them, and blessed them.

Notice Jesus’ first word in this passage, “Let.” Let implies an already forward moving progression. The children are already coming; it is their natural inclination to seek connection. God has been longing, is longing now, and will continue to long for children, and, further, children are wired to long right back. The movement is already at hand.

What begins with forward motion continues on to what will hinder. Jesus says, “do not stop them,” which could be an indictment of the ministries for children and youth in the past and in our time. The past teachings of the church for training children in the way of Christ were created and implemented with good intention. However, many of these intentions have fallen short of acknowledging the full humanity of children or God’s capacity to meet children precisely where they are.

When we adults fall into broken patterns of thinking about children and about God, we tend to move toward models of babysitting, entertainment, or, worse, manipulation through shame and fear. Jesus seems to be asking less of the adult and more of the child. Jesus seems to be inviting the adult to empower the child and move out of the way. He is inviting the child to direct encounter.

A BROKEN PATTERN OF CONNECTION

My first conscious memory of God was in the La Sal Mountains in Utah. I was with my family and we had driven up and into the timber from our tiny town of Moab to cut firewood for the coming winter. As the adults began their work, I wandered off into a grove of aspen trees. If you’ve never seen aspens in autumn, imagine gold coins, suspended by tiny gossamer strings, glistening in the sunshine.

Aspen trees grow in groves. Underneath, in the dark richness of the soil, they are connected to one another by their life-giving root system. They live in close proximity to each other, and while each is a single tree, they are also a community. They share their health and their sickness. And on this particular day they seemed to be issuing me an invitation. I was only five years old but can still remember the sponginess of the ground, which was damp with morning dew and squishy from years of healthy cycles of decomposition. I bounded my way into the aspens’ presence.

All at once I had a sense of awe and perhaps glory. The space was so lovely, so inviting. I remember being drawn in. I wanted more of whatever this was, so I lay down on my back in their midst. I gazed up at the little coins, squinting from the intense brightness of the sun. It seemed like the earth itself was breathing, and I was breathing with it: slow and deep breathing of indescribable sweetness. A long-known reality began to be realized in me that day. I gradually understood that I was not alone. I can’t explain how I knew this, and I certainly couldn’t articulate that knowledge then, but I distinctly remember knowing that I was not alone, I had never been alone, and that whatever, whoever, was with me, loved me.

Fast-forward six years and my life was much different. A big family move to Texas and the daily comings and goings buried this experience in my memory. At the Christian school I attended, I sat at a tiny, isolated desk, surrounded by thin booklets of math, science, spelling, reading, all the usual culprits. I felt myself being swallowed by loneliness. The intellectual pursuits doled out to me in four-page increments were no salve for my soul. Each student was required to have a Bible in their possession and to memorize an assigned passage of Scripture each month. They were mostly passages around what Dallas Willard calls “sin management.”

In the midst of drudgery, curiosity and, I suspect, the gentle guidance of the Spirit led me to the Gospels, and I found a name for that someone who was with me in the aspens. I don’t remember what story of Jesus captured my heart first. All I can remember is an insatiable desire to be with this person Jesus. I grew to love him. My imagination was enlivened by his life, my heart was broken by his death, and hope found a source in his resurrection. I refused to complete my other assignments; all I wanted to do was read about, talk about, and, yes, even write minisermons about Jesus.

The universe of my little desk with my Bible was safe and full of life. The generous gospel was the lifeblood of this universe. It was in stark contrast to the rest of my world. The implicit theology of the school and the church was that all human beings are isolated from God unless they have spoken the words of confession until they had been broken by their sin and begged God to forgive them. To be sure, this was a lived reality for many adults, but God was as near as the breath in my lungs, and I had already grown to love him.

As an adult I understand why it was done, and I can empathize with the driving need to control outcomes. If theology is rooted in scarcity and logical conclusions lead to a fear that children will burn in Dante’s eternal fires of hell, there is no time to muck about with loving relationship. The children have got to be “saved” through any means. And that’s what happened. Manipulative and coercive means were used to convince the children to walk the aisle and say the prayer. This, we were assured, would save us from the impending devastation. My young mind understood that if I didn’t comply, I would be alone again. My family would be ripped away by the Jesus I had grown to love. Seeds of distrust were sown in my heart.

This must surely be what Jesus meant when he said, “Let the children come to me and do not stop them.” When fear is used to manipulate outcomes, it will cause a full stop. Danger doesn’t draw; it drives. Jesus was well aware of the adult propensity to control. Even in this passage his disciples are “speaking sternly” in an attempt to control the situation. Jesus does not put up with it. He is indignant and commands the adults to back down.

LONGING FOR GOD

What did Jesus know about children? That they are already drawn to connect with God. That coercion is a short-term, highly damaging solution to behavior management. That every person, especially a child, is wired to long for God. That direct encounter with the Father would change everything. He knew how to tap into this longing. He knew how to listen people to life.

I have seen this many times as I sit with children as a listening friend at Haven House. Our ministry is called holy listening, which is a period of time set apart for an adult to sit with a child and listen. Together the adult and the child listen to the life of the child, discerning where God has been showing up. On one particular day I was meeting with Sadie, who was ten. She and her mother had moved into Haven House seven months earlier. It was the longest she had ever lived in the same place. For many years they lived in their car, driving from Walmart parking lot to Walmart parking lot. At Haven House, Sadie was in school and had regular meals and a community surrounding her, but she still was struggling. She was contentious with the other residents, explosive with the staff, and rarely at rest in her body. The dedicated care providers at Haven House got Sadie into counseling, which helped.

Sadie also wanted to come to holy listening. Most weeks I sat with Sadie and listened to the disjointed stories of her life. In holy listening we sit on a white blanket as a sign of sacred space. Sadie entered the room with me but sat just outside of the blanket. This was her choice, and I honored it with no protest. After several weeks of meeting, I wondered how Sadie might respond to the Imago Dei Ministries Reflection Cards.3 The Reflection Cards are the brainchild of therapist Katie Skurja. The deck of cards contains photographs of superheroes, fictional cartoon characters, and other objects on which to project thoughts and feelings. We opened our time in the usual way: she sat just outside of the blanket, and I asked for grace. I introduced the Reflection Cards and invited Sadie to choose two cards that told a story about a time she knew God was with her.

Sadie chose her cards and arranged them in a shallow sandbox we used to draw prayers. “Can you tell me these stories,” I asked, pointing to the cards. She introduced her stories with the caveat that “these are not from today but over a while.” She told the story of a bullying incident that made her afraid. “But it wasn’t the scariest.” She went on to say, “The scariest was the day my dad and brother got in a fight.” I asked, “Where was God during the fight?” “Oh, he was there,” she said. “Only no one could hear him.” With the next card she told the story of swinging at school and singing. She described how God was all around her, lifting her up, and singing with her. “He likes it when I sing,” she said. Then she shifted her focus to drawing patterns with her fingers in the sand around her pictures. She asked if she could use the blocks in the sand too. I agreed that it was a brilliant idea. “You can use this time to talk with God about your stories,” I offered. She nodded her head and then asked if she could move our battery-powered candle to the sand too.