Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

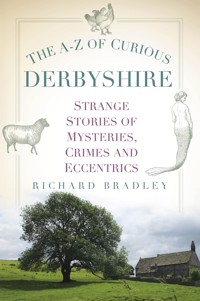

Derbyshire has long been a popular tourist destination. For centuries the crowds have flocked to fashionable towns like Buxton, and a large swathe of the county was incorporated into the UK's first National Park in 1951. But below these surface level attractions lie stranger aspects of county life, which tourists don't get to see. In The A-Z of Curious Derbyshire you will learn about local traditions from hen racing to well dressing, meet local eccentrics like the Matlock Amazon and the Wild Man of Bakewell, and discover sites mystifyingly absent from the local tourist board brochures, including the Devil's Shovel Full and the Buxton Shoe Tree.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Richard Bradley, 2023

The right of Richard Bradley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 8039 9297 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Acknowledgements

Introduction

A

A625 Road

B

Black Harry

Boggarts

Bown, Phoebe, the ‘Matlock Amazon’

Brittlebank vs Cuddy

Buxton Shoe Tree

C

Crantses, or Maiden’s Garlands

D

Derby Tup

The Devil in Derbyshire

Dragons

E

Elephants

F

Fire

G

Goitre, or ‘Derbyshire Neck’

Guising

H

Hen Racing

I

Ilkeston Charter Fair

J

Jughole Cave

K

Kenny, Betty

Kissing Bunch, Violence Provoked By

L

Lead Mining, Poetry of Mine Names

Location, Location, Location

Love Feast

M

Matley, Dorothy of Ashover

Mermaids

Mob Justice

N

Naked Boy Racing

O

Observatories

P

Padley Martyrs

Poor Old Horse

Q

Quarndon Spa

R

Rivalries

Rodgers, Philip of Grindleford

S

Salt, Micah, Buxton Antiquary

Sheep

Sheldon Duck Tree

Squirrel Hunting

T

Ting Tang Night

U

Unlousing

V

Vanishing Villages

W

Wakes Weeks, Mishaps and Tragedies

Well Dressings (Controversial)

The ‘Wild Man’ of Bakewell

X

X-Rated Material

Y

Yolgreff/Yoelgreve/Yoleg (... Etc.)

Z

Zoo

About the Author

Endnotes

Bibliography

Thanks to Nicola Guy and Ele Craker at The History Press.

Mum, Dad, Kate, Oscar and Leo.

Lynn Burnet, David Clarke, Graham Leaver (Chesterfield Astronomical Society), Nathan Fearn, Bret Gaunt (Buxton Museum and Art Gallery), the late Michael Greatorex, Ruairidh Greig, Rod Jewell, Jean Kendall, Geoff Lester, Helen Moat, Ross Parish, Benjamin Reynolds (Media Archive for Central England), John Roper, Judy Skelton, Sam Reavey (Dronfield Heritage Trust), Matthew Hedley Stoppard and family and friends, John Widdowson.

The staff of Derbyshire Libraries, Derbyshire Record Office, University of Sheffield Special Collections.

All photographs either taken by the author or from author’s collection unless otherwise indicated.

With its stunning scenery, Derbyshire has long proved a draw for tourists and day trippers. The Peak District (often thought of as synonymous with Derbyshire in the popular consciousness, although the area it encompasses in practice also spills over into the neighbouring counties of Staffordshire, Greater Manchester, Cheshire, and South and West Yorkshire as well) was designated the UK’s first National Park in 1951.

I spent the first nineteen years of my life growing up in Derbyshire (since the year 2000 I have lived just over the border in Sheffield, but pay frequent return visits), and a particular interest of mine is in the county’s folklore and customs. I have previously put forward the theory – and no one has so far presented a successful counter-argument – that of all the counties in the UK, Derbyshire has the greatest density of calendar customs – ritual events that take place on a certain day each year to mark the turning of the seasons.

Some of these customs, like well dressings and the Castleton Garland ceremony, are clearly of very ancient origin. It has been speculated that these kinds of folk traditions may have survived for longer because until the railways started to penetrate Derbyshire from the mid nineteenth century onwards, the state of the roads was so infamously poor that there was a relatively low degree of population flux as people found it so difficult to get in and out of the area – hence old traditions had a greater chance to be passed down through families in a relatively ‘undiluted’ stock of residents.

Despite the influx of tourists into the area over the centuries, there can still be a lingering sense of insularity to some Derbyshire towns and villages to this day, making them a potent breeding ground for eccentrics – it’s no coincidence that dark BBC comedy The League of Gentlemen decamped to the county to film the majority of their exposé of smalltown life (see Location, Location, Location).

Within the pages of The A–Z of Curious Derbyshire you will encounter a selection of Derbyshire’s many strange ‘characters’ over the years, and the myriad bizarre things they have managed to get up to during their time on earth, as well as strange quirks of the landscape and local legends.

A625 ROAD

The story of the doomed A625 road begins in 1819, when the Sheffield & Chapel-en-le-Frith Turnpike Company constructed a new thoroughfare skirting the base of Mam Tor as an alternative to the nearby route through the steep-sided Winnats Pass. The name Mam Tor means ‘Mother Hill’ but another local nickname for the hill (which the folks at the Turnpike Company would have been advised to have paid more heed to) is the ‘shivering Mountain’, on account of its propensity for landslips due to unstable lower layers of shale.

The post-apocalyptic landscape of the collapsed A625 road at Castleton.

As the number of motor vehicles using the road increased in the twentieth century, the necessary closures and repairs became a regular occurrence, with major works having to be undertaken in 1912, 1933, 1946, 1952, 1966 and 1974. All efforts to shore up the road to traffic were finally abandoned in 1979 and the road was closed to cars once and for all. The decaying route remains open to walkers and cyclists, however – an unusual landmark on the outskirts of the tourist Mecca of Castleton to complement the village’s several show caverns, tea rooms and souvenir shops selling the locally mined mineral Blue John.

Walking its length while avoiding the many cracks in the tarmac and sudden drops is something of an unsettling experience: it doesn’t take much stretching of the imagination to envisage that you are walking through some kind of post-apocalyptic landscape. The crumbling section of A625 that remains at the base of the Shivering Mountain is a handy reminder that for all our collective ingenuity and entrepreneurship, in a game of Top Trumps, Nature would be a higher-scoring card than Humans.

BLACK HARRY

Black Harry was a notorious Derbyshire highwayman of the Dick Turpin mould, active on the remote moorland roads surrounding Stoney Middleton in the eighteenth century. His ‘career’ finally came to an abrupt end when he was captured by local law enforcers and gibbeted at Wardlow Mires. Harry’s soubriquet stems from the way he used to blacken his face in order to disguise himself.

Despite his life of violent crime, terrorising people who passed through the Peaks, Black Harry has since had a degree of posthumous respectability bestowed upon him, as one of the remote country lanes above Stoney Middleton that he formerly stalked looking for suitable passing victims has had the name ‘Black Harry Lane’ conferred upon it. In 2011 the Black Harry Trails, a series of ten routes suitable for horse-riding and mountain-biking that converge on Black Harry Gate, were opened, having received funding from the Derbyshire Aggregate Levy Grant Scheme and support from the Peak District National Park Authority, Derbyshire County Council, landowners, residents and local businesses. These routes can nowadays be enjoyed recreationally by anyone with the desire to get out and take in the fine surrounding countryside without the threat of being asked to ‘stand and deliver’.

Black Harry Lane above Stoney Middleton.

BOGGARTS

A boggart is a North Country name for a supernatural being. The phrase was a fairly loose and adaptable one, as a boggart could take the form of a ghost, phantom dog, troll-like figure, or even a real-life flesh and blood resident of a village who was a little ‘suspect’ or reclusive – children were advised that they were ‘boggarts’ so that they would know to keep their distance. T. Brushfield, J.P., writes in his reminiscence of growing up in Ashford-in-the-Water that every ‘nook or dark corner’ seemed to have its own boggart, and that the boggart was invoked as ‘a sort of domestic policeman, […] used to scare obedience from children, by the agency of fear’, and that as well as invented supernatural phantoms, ‘some old man or old woman was used as an out-door terror’.1 Similarly, the children’s authoress Alison Uttley, who grew up at Castle Top Farm near Cromford, writes of looking out of the window of the farm and seeing ‘an elderly figure we called the Boggarty Man, a poor man who set traps for rabbits in the lane’.2

At the White Peak village of Winster there are two resident boggarts who patrol either end of the village – the Chadwick Hill or ‘Chaddock’ Boggart at the Elton end, and the Gurdhall, Gurdale, or ‘Gurda’ Boggart at the Wensley end. According to notes that Dave Bathe took down when interviewing village native Allan Stone in 1983, the Chaddock Boggart is supposed to follow you up Chadwick Hill – ‘you can hear its footsteps but if you look there’s nothing there – it leaves you with a hideous laugh’. Whereas the Gurdhall Boggart was ‘supposed to be the ghost of the person who used to prevent children wandering away from the village – [it] stands in front of you on the road’.3 According to the Peakland Heritage website, ‘The Gurda Boggart has a long history of scaring travellers around Gurdale Farm near Winster. A young woman named Sarah Wild was once walking back home this way. Somewhere near Gurdale Farm she was accompanied for a while by “something”. She could only ever describe it as “a face”.’4

There might be a more prosaic reason for how these local legends first came into being, as Bathe’s notebook records: ‘Winster ghost stories – George Stone reckons that they were put around by poachers to keep people from poaching grounds at night.’ (In much the same manner, many of the UK’s phantom myths and legends relating to coastal areas originate from smugglers concocting and spreading stories to ensure people didn’t go nosing into their hiding spots.)

After giving a talk about local folklore and customs to the Winster Local History Group in 2018 that mentioned these local boggarts, I was sent an amusing anecdote concerning the Chaddock Boggart by Lynn Burnet of the Elton Local History Group, who was present on the night: ‘[The Chaddock Boggart] frightened an Elton girl out of her wits in the 1950s when she was walking up the hill at night. It followed her on the other side of the wall, breathing heavily, and she could just make out an undefined ghostly white shape. It turned out to be a Friesian cow and in the dim moonlight it was only the white bits that were just visible!’5

At nearby Birchover, the resident boggart was called the Shale Hillock Boggart, and he lived in the Boggart Hole that was located on the New Road (B5056) between Eagle Tor and Stoney Ley Lodge. In actual fact, his ‘lair’ was a ventilation shaft for the Hill Carr Sough that de-watered the lead mines of Youlgrave, discharging into the River Derwent at Darley Dale. The late Birchover resident Jim Drury speculated in his memoir of village life ‘Fetch the Juicy Jam!’ and other Memories of Birchover, that the Shale Hill Boggart may have been devised for practical reasons, too. Even in the 1930s, the road, with its windy bends and lack of pavement, could prove hazardous, with veteran cars, steam lorries servicing the local quarries and horses and carts all proving a potential danger to dallying pedestrians. Drury surmises that the Boggart could have been fabricated by village parents to scare their children away from playing in this dicey stretch of road.

At Brassington the local boggart conjured up to scare children into compliance was called the Sand Pit Boggart. The Kinder Boggart was one of many spirits reputed to haunt the wild moorland country around Kinder Scout in olden times.

The Glossop Record of 4 February 1860 reported that ‘the susceptible people of Whaley [Bridge]’ had been ‘put into a great fear’ by reports of a boggart basing itself at Shallcross Mill. The paper reported the opinions of some of the more rationally minded members of the townsfolk, who speculated that the presence may have been an otter, although the paper quashed that suggestion on the grounds of there being no fish for the hypothetical otter to eat at the mill, and concluded that ‘it is the intention of the rifle corps to assemble on Saturday night about the time of its appearance, and have a shot at it’.6 In the same paper’s 15 December edition of 1866, a correspondent going by the splendidly Dickensian-sounding name of Oliver Fizzwig sketched a journey ‘From Glossop To Disley and Thereabout’ in which he recorded the antics of the area’s notorious ‘Hagg Bank Boggart’, who terrorised the neighbourhood with repeated knocking. A clairvoyant was consulted, who diagnosed that the bad juju was emanating from a local resident who was radiating negative feelings towards his neighbours – but that this man would die in the early hours of the following morning. Sure enough, the clairvoyant’s prediction came to pass, and the boggart activity subsequently ceased.

‘Thart as fow and farse as a boggart’ was given as an example of ‘Popular Current Sayings of Everyday Life in Derbyshire’ by the Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal in 1878, meaning ‘You are as ugly and sly as a ghost’.7 Boggarts were such well-known phenomena in Derbyshire in days of yore that the terminology also found its way into local place names. Gorsey Bank near Wirksworth was the location of ‘Boggart’s Inn’ – no longer operational, although Boggart’s Inn Cottage and Boggart’s Inn Farm remain to the present day. A farm at Snelston was offered for sale in 1826 with various named fields, including one called ‘Boggart Close’, to the size of 4 acres, 2 roods and 26 perches.

Despite the fact that we now live in a more literate, scientifically minded and technologically advanced age, the influence of local boggarts has persisted in the folk memory of the area until recent times. David Clarke (2000) records that when the Planning Department of Derbyshire Dales District Council consulted local residents on a mixed use development scheme comprising shops and housing on the site of the former Cawdor Quarry on the edge of the town of Matlock in the 1990s, they received fifty replies, one of which questioned what effect the building activity would have on the site’s resident Standbark Boggart. The development did subsequently suffer misfortunes, with the work dragging on interminably following the economic crash of 2008, although this can probably be laid at the door of bankers rather than boggarts.

BOWN, PHOEBE, THE ‘MATLOCK AMAZON’

By the eighteenth century Matlock and Matlock Bath were both well on the way to becoming the inland tourist resorts they remain to this day, and it was in 1771 in the former town that one of Derbyshire’s most remarkable characters was born. Over the course of her long lifetime (she died aged 82 in 1854), Phoebe Bown amazed both locals and tourists alike with her eccentric behaviour, but in spite of her repeated breaking of society’s codes and conventions she seems to have been universally accepted by all as a local ‘character’. Indeed, in her old age she even earnt the patronage of local aristocrat the Duke of Devonshire, who supplied her with an old-age pension in an era long before the welfare state introduced this same benevolent function for all and sundry (Bown’s cousin’s daughter had married the Duke’s chief garden designer Sir Joseph Paxton, which is how she came into his orbit).

Phoebe Bown was the daughter of a local carpenter named Samuel. She seems to have inherited many of her father’s practical skills, as it is said she single-handedly built an extension to her cottage to house a harpsichord she had been bequeathed. Music was another of her skills, and in addition to the harpsichord she could turn her hand to the flute, violin and cello, and played the bass-viol at Matlock’s St Giles church. She was also said to have enjoyed the works of Milton, Pope and Shakespeare.

An encounter between Phoebe Bown and the Birmingham manufacturer William Hutton, when the latter was travelling through Matlock in 1801, repeatedly emphasised Bown’s mannish qualities when Hutton came to write up his journey for publication in the Gentleman’s Magazine. Her stamina for walking large distances was said to be ‘more manly than a man’s, and [she] can easily cover forty miles a day’. Hutton continued, ‘Her common dress is a man’s hat, coat, with a spencer above it, and men’s shoes; I believe she is a stranger to breeches. She can lift one hundred-weight with each hand, and carry fourteen score. Can sew, knit, cook, and spin, but hates them all, and every accompaniment to the female character, except that of modesty. […] Her voice is more than masculine, it is deep toned.’ Despite laying on with a trowel how masculine Bown was in appearance and manner, Hutton goes on to reassure us that she ‘has no beard’.

BRITTLEBANK VS CUDDY

The Brittlebanks were a wealthy family who, for a 200-year period from around 1700, resided at Oddo House on the outskirts of Winster, in addition to owning a large amount of land and property in the village.

In 1821 the popular local doctor William Cuddie was courting Mary Brittlebank. Mary’s hot-headed brother, 27-year-old William, thought the match beneath her social standing, and after a confrontation at the doctor’s house accompanied by his brothers Andrew and Francis and friend John Spencer of Bakewell (described by one newspaper report as ‘another less successful admirer, it is said, of Miss Brittlebank’8), he engineered a duel between himself and Cuddie, which took place on the lawn of his home, Bank House, on 22 May. The outcome was that Cuddie (who appears to have been a very reluctant participant) was fatally injured.

Re-enactment of the fatal duel between William Brittlebank and William Cuddie on the lawn of Bank House, Winster, 22 May 2021.

By 1821 any romantic and heroic notions attached to duelling were fast vanishing with the changing mores of the time (the final fatal duel taking place on English soil in 1852), and the incident was viewed as cold-blooded murder. With access to so much family wealth, William Brittlebank escaped trial and the country, seemingly vanishing into thin air in a similar fashion to Lord Lucan (it is said he went to Australia). His brothers and Spencer faced trial at Derby Assizes in August 1821 for ‘aiding, abetting, and assisting’ in the proceedings. Such was the level of scandal caused by the events that the case was very keenly followed locally; the Morning Post reported that the court case ‘excited an immense interest in the County. At an early hour an immense crowd surrounded the County Hall, and the rush, when the doors were opened, was tremendous.’9The defendants, described by the Post as being ‘genteel and interesting young men’,10 were all found not guilty, prompting much ill feeling back in the village.

On 22 May 2021, 200 years to the day after the fatal occurrence, a troupe of Winster villagers performed a humorous re-enactment of the events leading up to the fatal duel, which was penned by local resident, retired academic and Secretary of the Winster Local History Group Geoff Lester. The play was performed in several locations around the village, culminating in a performance on the lawn of Bank House where the duel took place, with collections on the street raising £520 for the local Jigsaw foodbank charity.

BUXTON SHOE TREE

The traveller on the A515 Ashbourne Road heading out of Buxton meets a curious sight on the left-hand side of the road shortly before reaching Buxton Cemetery (perhaps you may be travelling out that way to visit the unusual grave of local antiquary Micah Salt (QV) contained within). A tree at the kerbside can be found sporting rather unusual growths – anything up to a hundred pairs of shoes dangle from its branches, twirling silently in the breeze. Some of this footwear has clearly been hanging from the tree for some time, as several have become enveloped by a mossy growth.

The photographer Sara Hannant includes a shot of the tree in her 2011 photographic survey of English rituals Mummers, Maypoles and Milkmaids, explaining in the accompanying text: ‘Buxton teenagers created the Shoe Tree in the summer of 2006 by throwing pairs of shoes, tied together by their laces, into the highest branches of the tree. Local explanations of the shoe tree include a communal ritual, rebellion, a practical joke or to signal a drug dealer’s territory.’11

A common phenomenon embedded within much folklore is to have a variety of competing theories spring up as to how a particular tradition came into being, but the differing explanations Hannant has collected as to the origins of the shoe tree demonstrate that this is not a trend that is solely confined to ancient customs originating hundreds of years ago in an age before mass literacy, and that despite all the advances and innovations we have seen in communications in recent years, folklore retains its power to generate a sense of mystery and legend into the twenty-first century.

A post about the tree on the local interest Facebook page ‘Buxton “spatown” & District Photographs’12 prompted a similar degree of speculation as to how and why the tree came into existence. Claims offered by way of response here ranged from it being a memorial to a young girl killed in a car crash; ‘It’s a form of urban graffiti, like love locks on bridges or coins in a tree stump’; ‘I thought it was all the shoes that got left behind when people have stayed at Duke’s Drive camp site’; and ‘I thought it was an old wives tale that hanging shoes in a certain tree would help with fertility’.

One local commented, ‘It was started by a gentleman who had lived in Tasmania and came to live close by … [who] passed away recently’ – a theory that appears to be corroborated with a degree of authority (although a variance as to the place of inspiration) by a subsequent comment: ‘My late father-in-law, Peter Wren, started that shoe tree. When he was visiting New Zealand he saw one there and basically he thought it will be a good idea to start [the] tradition here.’ If this is indeed the true story as to how the Buxton tree came to sprout so many pairs of shoes, then it turns out to be a custom that has been imported to Derbyshire soil from the opposite side of the globe.

Strange fruit: Buxton Shoe Tree.

In addition to the wide variety of theories as to why it is there, this strange landmark is by no means universally popular among Buxtonians, the same Facebook post drawing comments from townsfolk along the lines of, ‘A DAMN Eyesore. Cut it down’ (which to me seems a little unfair on the tree, which didn’t really have a great degree of choice in the matter), ‘I think it’s an eyesore & cruel to the tree. I’d like to take them all down’, and, ‘It’s littering of course’.

CRANTSES, OR MAIDEN’S GARLANDS

A ‘crants’, also known as a ‘maiden’s garland’, is a relic from a bygone age, formerly produced whenever a young unmarried (and therefore, in theory – if the societal conventions of the time had been adhered to – virginal) girl of the community passed away. They consist of delicate paper-hooped garlands that were carried ahead of the coffin at the funeral and subsequently suspended from the roof of the church. The word ‘crants’ is believed to be of Scandinavian origin and the practice is referenced in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, when it is said of Ophelia, ‘Yet here she is allow’d her virgin crants, Her maiden strewments and the bringing home Of bell and burial’, suggesting that the custom was known of in England since at least Tudor times.

These garlands were formerly a widespread sight across Derbyshire, with records of them once having hung at the churches of Eyam, Glossop, Hathersage, Heanor, Hope, Fairfield, Tissington, Ashover, Bolsover, West Hallam, Darley Dale, Ilkeston (where ‘fifty or more’ were said to have hung in the mid-1800s), Crich and South Wingfield (the latter survived into the twentieth century, but was destroyed under the instruction of a churchwarden named William Brighouse on the grounds that it was ‘nothing but a dust harbourer’).

It is a pity that this particular garland has not survived, as it has a story attached to it. In the eighteenth century the landlord of The Peacock Inn at Oakerthorpe was Peter Kendall, who was also a churchwarden at the parish church at South Wingfield. Kendall had a beautiful daughter named Ann who was courted by a young local farmer. Ann subsequently fell pregnant by the farmer but upon discovering this news the ungallant chap swiftly ditched her. Ann gave birth to a baby daughter but in view of the mores of her era she was said to be so affected by the shame and scandal that she subsequently died of a broken heart in 1745. At her funeral a garland was dutifully produced in her memory and hung in the church, until it fell foul of Brighouse’s aesthetic sensibilities. The farmer who failed to accept the consequences of his actions is said to have got his comeuppance one day while riding his horse past the church shortly after Ann’s burial. The church bells suddenly and unexpectedly began to clang out, causing his horse to rear up in surprise, which threw him to the ground, causing death by a broken neck.

A couple of the crantses normally kept in storage at St Giles Church, Matlock.

When this particular local story is retold, the farmer’s name is said to be unknown – perhaps the moral being that such caddish behaviour consigns you to oblivion and you don’t deserve to have your name recorded for posterity in the history books. While as a folklorist I hate to debunk a good folk tale, I did come across Anne (not Ann, as most tellings of the story have it) Kendall’s entry on ancestry.com.13 It tells us that she was born in South Wingfield on 1 November 1713, and did indeed die there in 1745 – as did her mother, Mary Kendall née Flint, thus making 1745 a doubly tragic year for Peter; did the scandal also finish off Mary as well? The record says that Anne’s daughter was named Ann Kendall (this time minus the ‘e’) and that she was born in 1745, with the date of her death unknown. Intriguingly, in Anne’s entry we also have a spouse listed – a Thomas Dodd. Could this be our unchivalrous farmer? If so, contrary to the accepted version of events, did they marry after all? Or was Kendall married to Dodd and having an extra-marital affair with the farmer? Dodd does not have either a birth or death date recorded alongside his name, thus giving us no further clues as to his identity.

Crants on display at Holy Trinity Church, Ashford-in-the-Water.

The antiquarian magpie Thomas Bateman of Lomberdale Hall near Middleton-by-Wirksworth, an enthusiastic archaeologist frequently to be found digging into prehistoric burial sites in the surrounding Peakland countryside, acquired a pair of garlands from St Giles at Matlock and placed them in his private museum within his house for posterity. A 1911 Folklore article stated that some from the same church had been sold to tourists as ‘curiosities’.

Happily, St Giles still has a handful of crantses in its possession – one of which has been restored thanks to funding from the Churches Council and placed on display in a glass case in the vestry, with a further five kept in archival storage boxes. On a fieldwork visit to St Giles, churchwarden Brian Legood kindly retrieved three of the examples from storage that are not normally on display for me to photograph, as can be seen in the photo reproduced on the previous page.

Nowadays, in addition to the Matlock crantses, the only surviving examples of this touching custom within Derbyshire are to be found at the churches of Ashford-in-the-Water, Trusley, and Ilam on the Derbyshire–Staffordshire border. Whilst the Derbyshire examples are particularly well documented, it was not a custom that was unique to the area, with other surviving crantses to be found elsewhere in the country at churches at Beverley, East Yorkshire; Robin Hood’s Bay, North Yorkshire; Springthorpe, Lincolnshire; and Abbots Ann in Hampshire.