Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

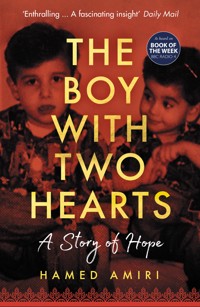

** The story that inspired the stage adaptation of the Amiri family, recently performed at the Wales Millennium Centre in Cardiff ** A BBC RADIO 4 BOOK OF THE WEEK 29 JUNE - 3 JULY 2020 READ BY SANJEEV BHASKAR (GOODNESS GRACIOUS ME, THE KUMARS AT NO. 42 AND MORE) 'Enthralling ... A fascinating insight' Daily Mail 'An inspiring read' Nihal Arthanayake, BBC Radio 5 Live A powerful tale of a family in crisis, and a moving love letter to the NHS. Herat, Afghanistan, 2000. A mother speaks out against the fundamentalist leaders of her country. Meanwhile, her family's watchful eyes never leave their beloved son and brother, whose rare heart condition means that he will never lead a normal life. When the Taliban gave an order for the execution of Hamed Amiri's mother, the family knew they had to escape, starting what would be a long and dangerous journey, across Russia and through Europe, with the UK as their ultimate destination. Travelling as refugees for a year and a half, they suffered attacks from mafia and police; terrifying journeys in strangers' cars; treks across demanding terrain; days spent hidden in lorries without food or drink; and being robbed at gunpoint of every penny they owned. The family's need to reach the UK was intensified by their eldest son's deteriorating condition, and the prospect of life-saving treatment it offered. The Boy with Two Hearts is not only a tale of a family in crisis, but a love letter to the NHS, which provided hope and reassurance as they sought asylum in the UK and fought to save their loved ones.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 371

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE BOY WITH TWO HEARTS

A Story of Hope

HAMED AMIRI

v

To my older brother Hussein who was my role model, inspiration and my best friend for life; to my mother who has sacrificed so much for me to be alive, well and to have a normal life; to my dad who quietly put his life on the line for all of us and has been a soundboard for every problem I’ve ever had; to my younger brother who has always stood by my side no matter how bad it got.

vi

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Herat, home. 2000

There was nothing special about our house in Herat, but it was all I knew as home until I was ten years old. It was built of clay, like all the other houses in our neighbourhood, and it was made up of four fairly bare rooms, with Persian rugs covering the floors. We lived with the families of two of my Dad’s brothers, so it was always full and busy, and my brothers and cousins and I were always causing trouble.

There was a kitchen area where Mum would make kichiri, and a sitting and dining room with no sofas or dining chairs, only patterned pillows or nalincheh. We didn’t eat our meals at a table, but around the sofra, an eating area on the floor.

The Taliban had taken control of Herat before I could remember, and rules in the city were strict. Curfew was 8pm. No one went out after dark, and women weren’t allowed to go anywhere on their own. Even us children had to be 2careful who we spoke to, what we said and how we said it. The Taliban were everywhere, so it wasn’t a good idea to do anything to stand out.

I was the middle of three boys, the jokey troublemaker sandwiched between my cheeky, liked-by-all older brother Hussein and my quieter, more reserved little brother Hessam, and we were sheltered from most of what went on with the Taliban. But I would sometimes overhear the elders talking about what they did – stories of mercenaries decapitating civilians and quickly sealing the neck with hot wax so they could bet on which headless body would stay standing the longest.

Then, one bright, and surprisingly warm winter’s day when I was ten, everything changed. I had run home to fetch our football – a crumpled piece of lightweight PVC wrapped in another torn plastic bag – and as I went into the house I could hear Mum’s voice from the kitchen. She was practising a speech she was writing. Word that this speech was happening had spread around the community, but in hushed voices.

‘We have the same rights as men!’ She paused, repeated herself quietly, and then shouted it. ‘We have the same rights as men!’

This kind of talk was normal in our house, but I knew it spelt danger. Mum’s interest in women’s rights had begun a few years ago when some of the other mothers in the neighbourhood had asked her to mentor their teenage daughters. Mum had a reputation for being an amazing cook, and she was brilliant at sewing. The neighbourhood mothers were keen for their daughters to learn the home skills they would need when they got married and, having only sons, Mum enjoyed teaching them. She treated them like daughters. 3

But as the girls she mentored came and went, Mum began to realise that once they got married they wouldn’t be much more than servants for their new husbands. How could she prepare them for that? The Taliban rule meant that girls had few rights anyway – they weren’t allowed to go to school and had no choice but to wear the full burka. Outside the home they were considered useless.

Mum was going to give her speech the next day, which was a Friday. The community would be coming together for Jummah, the Friday prayers, and as many people as possible would hear it. But that meant it wouldn’t just be the women she was trying to help who would be listening; the Taliban would hear it too.

I watched from the living room as Mum moved around the kitchen, making the dinner and practising her speech. Then Dad came in.

Dad was Mum’s biggest fan. He was always getting under her feet and bustling around the kitchen, but he always supported her. He didn’t look like most Afghans – he was fair-skinned with hazel eyes – and he had run a china shop with one of his brothers before opening the pharmacy where he now worked. Family was everything to him, and he backed Mum’s ambitions to fight for female equality. But he also loved us all and wanted to protect his family, and he knew Mum’s speech was dangerous. Opposing the Taliban publicly would put all of us in danger, and over the last few days we’d noticed his nerves starting to show.

‘Where are the boys?’ he said now. ‘The whole neighbourhood knows about your speech. I really hope you know what you’re doing.’ 4

Mum looked up from the stove for a second and then turned back to what she was doing.

‘They’re playing football,’ she said. ‘And don’t worry about tomorrow – we have God on our side.’

I crept out and went to find my brothers.

Our football pitch was a dusty alley in the neighbourhood where we had piled rocks up as goalposts. It was quite late when I arrived back with the ball, and the sun was already going down. I was always on the same team as my brother Hussein and played behind him, moving around the pitch so he was always in my sight. Although Hussein was four years older than me, Mum had trained me to keep a watchful eye over him, and I was always looking for any sign that he was in trouble.

Hussein had had a rare heart condition since he was born. He’d already had two operations in India: one when he was just a baby and another when he was six. But he’d got worse as he got older, and despite trips to Iran and Bulgaria to get help we were told that the only place he could get proper treatment was the UK or America. We knew that one day Hussein’s illness would catch up with him and we would have to leave Afghanistan, but for us that seemed far in the future.

In the meantime, I had become an expert at checking up on Hussein, watching his breathing, the way he moved and the colour of his skin. I took my responsibility very seriously.

Now, as I looked down the alley, I saw Hussein’s eyes light up as he spotted a gap in the opposition’s defence. He chased a perfectly placed through-ball. ‘Go on, Roberto Carlos!’ I shouted. 5

But as he powered off the line and skipped past his marker, he suddenly stopped and hunched over. I panicked. I could hear Mum’s voice in my head repeating her instructions: ‘Take his pulse, then get help.’

There was a beat of silence, then I took a breath and ran towards him.

‘Bro! You okay?’ I said, trying to sound calm. By the time I reached him he had crouched down in the dust, his skinny shoulders rounded. He looked up at me, panting.

‘Yeah, I’m fine.’

We’d been running around, he had raced down the pitch to get the ball, maybe he was just thirsty? No. I had a bad feeling about this.

I put my fingers on the right side of Hussein’s neck just as Mum had shown me and began counting. ‘One, two … wait …!’ I couldn’t keep up. It felt like machine-gun fire. My mind went blank for a moment, then I picked him up and put his right arm over my shoulder. I had seen football players carrying off their injured teammates like this. I could be a hero.

As we began stumbling home, I kept my fingers on Hussein’s wrist and eventually his pulse dropped to match mine. Of course, then he was quick to tell me that he could carry himself, so I let go but kept an arm around his shoulder.

As we turned the corner to our street, we could hear something loud and rumbling. Jeeps. These ancient Russian military vehicles were a common sight in our neighbourhood, and the militia in them would yell at each other and taunt passers-by. It was all just intimidation, and it became a bit of a game to us. We would duck out of sight and pretend we were in a war film. 6

This time, Hussein and I rolled under an old Volga. We began counting the passing vehicles. There were too many – way more than normal. This wasn’t just intimidation; they must be after something.

‘Mum!’ whispered Hussein.

As the jeeps got further away, we decided to follow, picking up the pace. I knew Mum was at home with Hessam, our little brother, and now Dad was there too, and the militia were heading in their direction.

But I also didn’t want Hussein to start clutching his chest again. I prayed for the best and ran as fast as I could, Hussein following just behind me. As I hopped over the mud walls, I counted each footstep against Hussein’s to make sure he was keeping up.

‘Go on without me,’ he said. But Mum had made me swear to never leave his side. She’d kill me if I Ieft him here. At each junction I stopped, peering round the corner to check for danger and to allow Hussein to catch up. As the clay house came into view, we saw the convoy making its way down our street. My heart thumped. We ducked into the crumbling house opposite us and watched in silence, our panting gradually slowing as we caught our breath. The jeeps weren’t stopping.

They rumbled further down the road and we sat back, relieved. But I was so angry. How dare they intimidate us like that? I picked up a broken brick and started to run after the jeeps. But Hussein grabbed me and put his arms around me from behind.

‘Don’t! Are you mad?’ he said. His heart was racing against my back and I knew I had to calm him down. I dropped the brick and kicked it. 7

‘Sorry, bro.’

*

That night we were all quiet around the sofra. Hessam and I sat either side of Hussein as usual, but instead of squabbling and joking we all quietly fidgeted on the rug. The food was delicious as always, but it was difficult to enjoy it as all I could think about was what might happen when Mum gave her speech tomorrow. Finally, Dad broke the silence.

‘Can’t you tone down the speech, Fariba? Be less critical of the Taliban?’ Although Dad was proud of what Mum was doing, I could tell he was nervous about what might happen.

Mum was quick to defend her cause. ‘Like they tone down their injustice? Have you forgotten how they threw boiling water at my own mother?’ She looked at him defiantly, and we were all silent again.

‘What about the children? At least think about them,’ Dad said.

Mum was growing impatient. ‘Think about the children? Okay. Do you want your children to grow up in an Afghanistan run by thugs? This isn’t about us or our children, Mohammed. We need to take back what they have taken from us. We need to take back our future.’

Dad looked at us and then back to Mum. ‘You know I’m with you to the end, don’t you, Fariba? Come what may? There’s no going back now, that’s all. God help us.’

As we carried on eating I looked across at Hussein. His lips were turning purple again. I quickly nudged Hessam, who made a gesture at Dad without Mum noticing. But when I looked back at Hussein I saw his colour returning. 8

Every night, Mum would tell us a story after tucking us in to bed. The three of us slept in the same small bedroom with its single barred window looking over the street. Mum would usually decide the story for us, but that night Hessam beat her to it.

‘Mum, why did the Taliban throw hot water at grandmother? Does it give people fiery tempers like you?’

Mum settled herself at the foot of the bed, smiling.

‘I’ll tell you about your grandmother,’ she said. ‘There was a time in our city when there were schools just for girls, so they could get an education just like you. But the Taliban shut them down. Your grandmother – and others like her who fought for equal education – were violently humiliated …’

Grandma sounded like a fierce woman. I could see where Mum got it from. I wondered what I would fight for when I grew up.

CHAPTER 2

The speech

The next day was Friday. As the three of us walked to school, neighbours, shopkeepers and acquaintances were quick to express their excitement for Mum’s big day. We thanked each one nervously. ‘We’re so going to be taken hostage,’ I said to Hussein, and he punched me.

Every street corner of our fifteen-minute walk felt like the end of the line. At school, the teacher wrote something on the blackboard about pomegranate seeds being like tiny rubies, but I couldn’t concentrate. I was more focused on what the other boys were whispering. Even the class bullies were quieter today. Maybe they thought we were going to be taken hostage too.

Mum had told us to go straight to another school in the neighbourhood when the last bell rang. She would be giving her speech in the playground. As we walked through Herat there were women in the streets, lots of them, all heading 10the same way as us. There was a weird kind of energy, and I couldn’t work out if this was good or bad. My imagination ran wild. Perhaps Taliban informers had betrayed Mum’s cause and were plotting another massacre?

As we arrived at the school, we saw a makeshift podium that clearly was able to be dismantled as quickly as it was put up. The audience, almost all of them women, were still arriving and there was hardly any room left in the playground. I thought I was good at counting, but I started running out of hundreds as I scanned the crowd. Apparently we were guests of honour, and we were ushered to the front to watch as Mum got ready to climb the wooden step ladder to the podium. Suddenly she came over and crouched down beside us. Her hands were shaking.

‘You know I love you all,’ she said. Her voice was trembling too. I couldn’t work out whether she was scared or excited, but she kissed us all on the forehead and told us again how much she loved us. What was this? Was she saying goodbye?

Mum opened her speech with the usual ‘God is great’, and everyone went quiet. The people in the audience seemed as nervous as she was. I looked up at Mum and then at the crowd. People were nodding and shouting ‘Inshallah!’ (‘God willing!’) as she spoke about making family values part of our vision of a new Afghanistan. I’d heard other people talking about this, so it was nothing unusual. But for a woman to stand up and talk about it like this in public was unheard of – and dangerous.

The rest of the speech was a blur. I remember a few bits – the Taliban, unity, extremism, freedom – and I remember 11the audience clapping and cheering. When Mum had nearly finished, she had to wait for the chants of ‘Down with the Taliban’ to stop before she could make herself heard. She finally ended by calling for unity and courage, and everyone clapped loudly.

Mum looked like a winner in a fight as she walked off the stage. We couldn’t help but smile as she came towards us, and I felt so proud of her. Despite the laws on hugging and kissing in public, Dad gave her one of his signature bear hugs, and we giggled as the school headmaster ran over quickly to pull him away. Didn’t Dad know that the rooftops of the houses all around had a view of the playground?

Mum kissed us again and I felt a sense of relief. But it didn’t last long. Well-meaning supporters in the crowd were starting to surround Mum, jostling and pushing to get nearer. She tightened her grip on my hand. My other hand was holding Hussein’s and I tightened my hold on him, trying not to fall over under all the people. I could hear voices asking Mum when they could visit her secretly. I could hardly stand up and the noise was terrifying.

‘We must be cautious and smart …’, I could hear her saying above the racket.

Then, as if by magic, the crowd disappeared. All those people were ready enough to rise to the challenge and make a difference, but they didn’t want to be seen by the Taliban. It was fair enough. The Taliban were good at making examples of their enemies.

As we walked home Mum had never held our hands so tightly. We were proud of her, and I think she was proud of herself, 12but she seemed nervous. Everyone in the street was looking at us, nodding at Mum in support. Mum’s speech wasn’t just about her of course, but we still felt proud of what she’d done. She’d been watching the cruelty of the Taliban for years, and now she’d finally been able to stand up to them.

Although it felt good to see how proud the neighbourhood was of Mum, we couldn’t wait to get home. We walked through the narrow streets and alleyways, Dad hurrying us along like a shepherd. He kept fussing at how slowly we were walking, and rushed us impatiently. He only seemed to relax when we could see our front door.

He half pushed us into the house and, looking around, locked the door behind us. This was a first – our door was hardly ever locked. So many of us lived in our house that there were always aunties and uncles, cousins and neighbours making their way in and out. Even though Herat was ruled by the Taliban, ours was a relatively safe neighbourhood on a quiet road, and there didn’t feel much need for locked doors.

But I could feel Dad’s relief. He bustled around Mum, trying to distract her and keep us all busy.

‘Let’s have a celebration!’ he said. ‘Our favourite meal to mark the occasion. It’s been a great day, a memory we’ll never forget. A lesson of faith and belief.’

This was all for our benefit of course – Dad wanting to show us it would all be okay. They didn’t want to worry Hussein. But we weren’t going to say no to our favourite dinner. While Mum prepared the meal, Dad kept his mind busy by watering the plants. He seemed on edge, but no matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t hide the smile on his face. 13

We were a bit in awe of Mum that day. We’d never seen anyone stand up to the Taliban, let alone a woman. Mum’s bravery was normal in our house, but this was the first time it had crossed into the outside world. We were proud. We couldn’t stop talking about it, each going over our favourite part of the speech. For Hussein, it was seeing the faces of the women in the audience as they listened to Mum. For Hessam (mummy’s boy), it was when Mum kissed him and made him feel like a VIP.

I said it was the moment at the end of the speech where, just for a second, I caught Mum’s eye. I could see how happy she was, and I knew that she’d done something she really believed in. Mum wanted the little spark she’d created that day to grow into a big fire, and I wished she’d been able to do that.

There were no aunts, uncles or cousins for dinner tonight, just the five of us. This was a good thing: there would be more food for us. Mum had made our favourite lamb dish, ghormeh plough, and she batted my hand away as I tried to sneak some off the serving dish. It was gloomy outside, but inside our little sitting room was colourful and bright as slowly but surely the sofra was set and plate after plate of colourful food filled the floor. Meals like this were my favourite.

We sat down one by one, with Mum and Dad on each side to complete the circle. The circle was more than just a shape, Mum explained, which was why we all had to wait our turn to sit. ‘Family is the most important thing,’ she said. ‘We don’t know what lies ahead, but what we do know is that family, love and sticking together – no matter how tough or scary life is – that’s the key.’ 14

We were used to these life lessons of Mum’s. But secretly we loved it. I started to understand why Mum had given her speech, despite all the danger. Food was forgotten for a minute, as we looked at each other silently. It was a strange moment that has stayed with me since that day – it was as if we were inside a bubble, oblivious to everything outside of our circle.

Just like any bubble, sooner or later it had to burst. As we ate together, we had no idea how life-changing the events of that day would be.

We weren’t expecting anyone, but when the knock at the door came we still thought it must be one of our uncles. Dad walked cautiously towards the door. We all hoped for a friendly face as he asked loudly, ‘Who is it?’

‘It’s me. Open the door, quick,’ came a whisper. Relieved to hear the friendly voice of our uncle, or amu, Dad rushed to unlock the doors to embrace him. But we could tell something was up – his voice was panicked, and before Dad could even hug him or say hello he pushed the door shut behind him.

‘Close the door, lock it!’ he said. We’d never seen Uncle like this before. Dad looked worried.

‘What is it? Is the family okay? Sister is unwell … how is her health?’

Uncle looked past Dad at us sitting at the sofra. We rushed up to hug him, but his smile was fake. Even without Dad’s worried face in the background, we knew something was wrong. Uncle’s hug was tighter and lasted longer than usual. Reluctantly we went into our bedroom to let the adults talk. 15

Hessam was being annoying, and Hussein tried to distract him while I tried to listen in to the adults’ conversation.

Uncle called Mum over, and we heard Dad say, ‘Please, tell me what has happened. Is everyone okay?’

‘They heard the speech,’ he whispered. ‘They’re looking for you.’

‘Okay,’ said Dad. ‘What else? Please, just tell us.’

Uncle spoke so quietly I could hardly make out what he said, but I heard, ‘The mullah has given an order.’

This was it. All our fears in one sentence. We called the mullah the ‘executioner’, and we were terrified of him. He had turned our local football pitch into a place of execution, and it was now referred to as ‘the pit’. People would gather there to hear death sentences passed on people who spoke up against the Taliban. Later they’d be executed. Someone must have told them about Mum, and now they wanted her dead. 16

CHAPTER 3

The Amiri market

Although I’d always lived under Taliban rule, I never thought it would affect us like this. It had just been everyday life. We’d always known that Hussein’s health meant we would one day have to seek help from doctors outside of Afghanistan, but we hadn’t prepared for the fact that Afghanistan would no longer be a safe place for us. Despite all the troubles with the Taliban, Afghanistan was our home, a familiar place. I’d never known anything else. I realise now that home isn’t where you live, it’s the people you live with. And you can take them with you anywhere.

Now we were in danger, and the only thing to do was escape. I was a naturally nosy child, always listening at doorways, wanting to know what the adults were talking about. But this time my nosiness had led to me hearing something I didn’t want to hear. I wanted to tell my brothers, but I knew 18the stress it would put on Hussein’s heart, so I kept it to myself for now. I supposed they’d know soon enough.

Playing dumb, I moved away from the door and went back to Hessam and Hussein. Hessam didn’t notice anything different, but I could tell Hussein could see that I knew something. He probably knew I was hiding it from him because of his illness too.

While we waited in the bedroom, the adults were debating in loud whispers in the other room. What were they talking about? How we could hide from the Taliban? Or how to find a way to get out? That would need money, which I knew we didn’t have. It would also mean knowing the right people – the ones who went under false names, the ones who promised a safe haven. I already knew so many stories of people who had died trying to leave. Would it even be safe? Whatever my parents were discussing, I knew it would involve a journey, and I was terrified of it.

Finally, we could tell by the hugging and kissing that Uncle was leaving, and shortly afterwards we heard the front door being locked. It was time to face the music. Hussein wanted to go straight through to the other room, but I didn’t want to, and tried to distract myself with toys. Eventually, Mum and Dad came through to us.

Dad was struggling for words, so Mum started.

‘Firstly, I want you all to know that we’ll be okay,’ she said. ‘As long as we’re together.’ We didn’t say anything. ‘Because of my speech, the mullah has made a decision. We’re not safe here any more. We’re going to need to leave quickly, and we’re going to have to sell our things to raise enough money. There are people who can help us, but we have to 19pay them before they’ll do anything. Even if we sell everything we might not have enough. Then we’re going to have to go on a long journey, to a place we don’t even know yet. We didn’t want this, but we’ve got no choice. And we will be okay.’

When Mum had finished, Dad asked if we had any questions. For some reason, at that point we didn’t have much to ask, although afterwards I thought of a hundred things I wanted to know. Uncle was going to try to buy us some time, but our only chance of survival lay in the hands of traffickers. They only spoke one language: money, so the first thing to do was to raise as much as we could.

In a community like ours, fear of the Taliban brought people together, but we were soon to learn the strength of the love and respect for our family in our neighbourhood. The next day friends and family gathered in secret, and within a few hours of the word spreading our house had become a market. Everything we had – from dishes and cooking utensils to toys and books – was for sale. There was no time to price things up, we just needed enough money to pay for our escape. Mum laid everything out like a bazaar: clothes, rugs, curtains and bedspreads were draped across furniture, while bowls and crockery were stacked in corners. Our neighbours poured into the house, picking up items and offering money. It was unlike any market we’d ever seen. No one haggled, and people even paid over the odds for items they didn’t want or need. We couldn’t believe the support from our community.

The Amiri market was fun, and Hessam and I enjoyed showing people our belongings and counting the money. Mum was quiet though, and I realised that this must be hard 20for her. She was selling everything she owned, the memories and the laughter from our house, in a scuffle of people she knew well. Hessam insisted on selling his favourite toy, saying he’d grown out of it anyway, but this seemed to upset Mum more.

Within a few hours the Amiri market was closed, leaving us with four bare walls and the clothes we stood up in.

‘I’m sorry, boys,’ Mum kept saying. But we didn’t think of it like that. Why should she be sorry? Yes, she was the one who had given the speech, but we all believed in what she was doing. We were a family, and families stick together, remember?

So our house was empty but our hearts were full. Our friends and neighbours had helped us when we really needed it, and we felt like a team standing up to the Taliban. I hoped that Mum’s speech was just the beginning, that somehow what she’d started would carry on after we’d left. I also hoped that we’d be able to come home one day.

Raising the money to pay the traffickers was only half the problem. Our real enemy was time. Dad’s next mission was to find the right people who could help with our escape, and so began a frantic search for someone who could put us in touch with a contact. We never asked where we were heading – it didn’t seem to matter. Our destination wasn’t important, as long as it wasn’t Herat.

While Dad was busy trying to connect with the underground trafficking world, Mum helped us to pack. After the market we didn’t have much – just two sets of clothes each. But we didn’t really miss our toys and books. We knew that life was about surviving now. 21

As we packed we teased and jostled with each other as brothers do, but Mum was deep in thought. ‘Are you okay, Mum?’ Hussein asked.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘I’m just thinking about all the women we’re leaving behind. The women I’ve been fighting for.’

She looked disappointed, but I knew it wasn’t just that. As she stared at the empty rooms I knew that she was heartbroken to leave the house where she’d married, where she’d brought us up and created all our memories. I realised that we were leaving our friends and family too. Would we ever see our cousins again?

As it started to get dark, the only fruits of Dad’s enquiries were that we would hear back soon. But would ‘soon’ be soon enough? We knew that the Taliban were out there searching for Mum. Were they scouring the streets for her? Could they find her right here, in our house? No one ate much that evening, and the sofra was a different place to the night before. 22

CHAPTER 4

Escape on the roof

That night, after the market, we rolled our clothes under our heads as pillows and talked each other to sleep. Our spare jumpers became duvets for the night and the house felt empty and cold. I slept okay, but I woke to the sound of loud hammering on the door.

I sat up in bed and saw that Hussein was already up, and panicking. I tried to keep him calm: now would not be a good time for him to have an episode. I talked to him calmly as he stood shivering in the bedroom, and I could tell that he was trying to calm himself down.

‘Go, take the boys,’ I heard Dad whisper to Mum, his eyes on the door. This was no time to argue. Mum came running in and grabbed us, and we ran up to the roof. It was freezing up there, but we sat, waiting, behind the clay chimney. I could feel Hussein’s hand in mine, sweaty, shaking. ‘Please 24God, look after his heart, look after his heart, look after his heart,’ I kept repeating in my head.

We heard some noises downstairs, and Dad’s voice questioning the visitors. Then we heard something terrible. A bang. We looked at each other in horror. Mum put her hand over her mouth, but we knew we had to stay silent. I couldn’t bear it. I could feel the panic rising up in my chest. Then there was chaos in the garden downstairs, and we couldn’t hear Dad at all among all the shouting and heavy footsteps. For a minute I was terrified that they were coming up to the roof and would find us there. Would they kill us? Had they killed Dad?

We could hear the Taliban coming into the house and making their way through all the rooms. There was nothing to take, nothing left at all. But what if they were looking for us? Mum seemed in a trance, and we tugged on her to snap her out of it. Then we heard a quiet hissing noise from across the neighbour’s roof.

‘Psst, psst.’ What was it? Suddenly we realised that a ladder was being placed across the two rooftops.

‘Over here,’ came a voice. It was Uncle! I grabbed the ladder and pulled it across the gap between the houses. We had to be quick – the Taliban weren’t going to stop looking for Mum. She wasn’t moving, so I grabbed her by the wrist and Hussein and I dragged her across the roof onto the ladder. One by one we scrambled across to the neighbour’s roof and hugged Uncle. Even in the chaos I remember he smelt like Dad, and I tried not to think about what might have happened.

Mum was silent for the rest of the day. She seemed to have lost all emotion. Uncle put on a brave face and 25organised everything, taking us to a neighbour’s house until we were sure the Taliban had gone. Then he left, I didn’t know where to. Was it to find Dad? Or to carry on where he left off, trying to find someone who could get us out of Afghanistan? But how could we leave without Dad? That was impossible.

That evening was gloomy, and for the first time Mum seemed really angry. Dad had stood by her through everything – it wasn’t fair that we didn’t know what had happened to him. At dinner with our neighbours the circle felt empty, incomplete.

I was worried about Hussein, too. Mum had always been there to look after his health, but now she seemed distant, preoccupied. Did that mean I was in charge? I kept replaying what had happened on the roof in my mind. Mum said she’d heard a shot, but I wasn’t so sure.

Just before bedtime that night, Uncle came back. We were desperate for news of Dad, but were afraid of what he might say. He’d been crying and was out of breath. Surely that was a bad sign?

‘It’s your Dad – he’s alive,’ he said. We ran towards him and squeezed him.

‘How?’ we demanded. Uncle rubbed his face and began to explain how the Taliban had taken Dad and were holding him captive. As far as he knew he was okay, but we had to get him out as soon as we could. He’d also managed to find some traffickers who could help us get out of the country.

Mum came in and rushed to us. She was crying. ‘What can we do?’ she said. ‘How can we find him?’ 26

‘We know where he is,’ said Uncle. ‘It’s just a case of getting to him. But I’ve got a plan. I’m going to go with the cousins tonight and try to get him out.’

‘They’ll have your throats,’ said Mum, nervously.

‘We’ll be okay,’ he replied. ‘Anyway, we have no choice. The Taliban aren’t patient, and the traffickers are ready to take you as soon as the whole family is ready.’

‘Take us? Now?’ Mum hesitated. We were leaving. As soon as we got Dad back we’d be leaving Afghanistan forever.

It wasn’t until afterwards that I discovered what happened that night when they rescued Dad. Uncle had used his connections through the pharmacy to find out where Dad was and paid off the security guard to persuade him to look the other way. Dad was in a pretty bad state when they found him, and it was a struggle to get him home in one piece. They’d more or less had to carry him through the streets, the cousins walking ahead to make sure it was clear.

That was the last time Dad saw his cousins.

We waited impatiently at our neighbour’s house, looking for any sign of Uncle and the rescue party. The trafficker was already outside, his foot on the pedal, the engine running. He said it was important to make the most of the cover of darkness, to get as many miles behind us as possible before daybreak.

I remember how annoying the engine noise was, and how the car lights shone down the street as we peered from the window into the darkness. I kept watching that space, waiting for any sign of Dad and the cousins. Finally, in the distance I could see a group of men walking up the lit-up street. It was 27them! Behind the cousins I could see Dad, walking slowly and with a limp. Uncle’s arm was around his shoulder, holding him up. He looked battered, bruised, but he was alive.

So those were our last moments in Afghanistan. It wasn’t a great goodbye – in the dimly lit street with the fumes of a car engine – but it was the last time we would see our house, our uncles and aunts, our cousins, our neighbours. Then everything changed. 28

CHAPTER 5

Moscow

We were told to get into the boot of the car, and the driver showed us a small hidden compartment underneath a fake top, so that if someone were to open the boot it would look like it was empty. There wasn’t much room, but we all bundled into it and tried to get comfortable. I could hear Dad’s rasping breathing, and we knew he must have broken ribs.

In any other circumstances we would have been excited about our first trip away from Herat. But this wasn’t what we’d imagined. We couldn’t see anything, and even the driver was obscured by a screen so that border guards wouldn’t be able to see into the back.

All we could do was hope that this journey would lead to a better life. I couldn’t even dream of what that would be like, but I wanted it to be somewhere where we could 30finally let our guard down and not worry about life and death. Somewhere we would be safe and could grow up to have a normal life. Somewhere Hussein could get better. Somewhere with no AK47s.

All of that felt so far off right now as we lay in the cramped space, knowing there would be a long journey ahead of us.

We were unable to keep track of time, but after what must have been days we came to a stop. Outside the car we could hear a commotion, and the driver told us not to make a noise. I wanted to follow instructions to the letter, so I held my breath. Not breathing in through my nose was actually a relief, as the smell in the car had become pretty bad. Hussein and Hessam copied me, and there was complete silence in the compartment.

Outside the car we could hear bad language and men talking aggressively. They were swearing at each other, but then they laughed. Finally we were taken out, put into another van, and we started moving again.

Here we were allowed to sit in the back, and as I looked out of the car window I could see the sky was pitch black. It was freezing – the coldest it had been since we left home – and the road was much bumpier than before. After a while I could see lights, and there were buildings – taller than I’d ever seen before, and I wondered if we were in a city.

Soon after that we stopped and again were all told to get out. The only thing I remember is that every bit of my body, from my neck to my legs, clicked as I unfolded myself from the car. I actually quite enjoyed this, as I always loved clicking my knuckles to make my brothers groan. 31

We stepped out of the car into huge dirty piles of snow at the side of the road. That explained why we’d been so cold in the car for the last few hundred miles. Dad pointed towards a metal door by an entrance to an apartment and followed us to let us in.

‘Moscow.’ Dad said. ‘We’re almost there.’ I didn’t know what this meant. Almost where? We didn’t even know where we were going. He smiled brightly, but I could sense he was uneasy.

The apartment was pretty dreadful, but it was a roof over our heads after days and nights of being in the back of cars and vans, so we were just happy to be out of that cramped space.

That night we all had the best sleep we had had for a while. It felt so good to rest on an actual bed instead of being cramped in a tiny compartment in a moving van. I couldn’t help but imagine what lay ahead – we’d been dreaming of getting somewhere safe for every hour, minute we were on the road that I started to wonder whether such a place actually existed. And even if it did, would we ever get there? Would we ever be safe?

The next morning, as the sunlight came through the blinds I tried to fight against waking up. We were all desperate for more sleep, but soon I could hear Mum pottering about in the little kitchen. Before long familiar smells reached my nostrils.

I kicked my brothers awake, and we dragged ourselves to the rusty dining table to eat our first proper breakfast in what felt like ages. It was only tea, bread and cheese, but it was so good. We devoured everything, fighting over the last 32crumbs of bread as usual, and then bickered over who would help clear up.

There was a TV in the apartment, but when I turned it on all the channels were in Russian. We didn’t care too much, as having a working TV felt like luxury, even if it was in a different language. We found a show we liked about a man who talked to his car – it was sleek and black with red lights and we’d never seen anything like it. We were glued to it.