Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A blistering, timely and gripping novel set at Cambridge University, centring around an all-male dining club for the privileged and wealthy. Hans Stichler's uncomplicated German childhood ends abruptly when his aunt invites him to study at Cambridge, where she teaches. She will ensure his application is accepted, but in return he must help her investigate an elite university society, the Pitt Club, which has existed for centuries, its long legacy of tradition and privilege largely unquestioned. But there are secrets in the club's history, as well as in its present, and Hans soon finds himself in the inner sanctum of an increasingly dangerous institution, forced to grapple with the notion that sometimes one must do wrong to do right.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in the United States of America and Canada in 2019 by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

First published in German in 2017 as Der Club by Kein & Aber AG

Copyright © Kein & Aber AG, Zurich – Berlin, 2017

English translation copyright © Charlotte Collins, 2019

The moral right of Takis Würger to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

The events, characters and incidents depicted in this novel are fictitious. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual incidents, is purely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 481 7

Export paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 477 0

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 911 9

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut in the framework of the ‘Books First’ program.

For Mili

Hans

In the south of Lower Saxony is a forest called the Deister, and in that forest there was a sandstone house where the forest ranger used to live. Through a series of chance events, and with the help of a bank loan, this house came into the possession of a married couple who moved there so the wife could die in peace.

She had cancer, dozens of little carcinomas lodged in her lungs, as if someone had fired into them with a scattergun. The cancer was inoperable, and the doctors said they didn’t know how much time the wife had left, so the husband left his work as an architect to stay by her side. When the wife became pregnant, the oncologist advised her to have an abortion. The gynecologist said a woman with lung cancer could still bear a child. She gave birth to a small, scrawny infant with delicate limbs and a full head of black hair. The man and the woman planted a cherry tree behind the house and named their son Hans. That was me.

In my earliest memory my mother is running barefoot through the garden towards me. She is wearing a yellow linen dress and a necklace of red gold.

When I think back to the earliest years of my life it is always late summer. It seems to me that my parents had lots of parties where they drank beer from brown bottles while we children were given a fizzy drink called Schwip Schwap. On those evenings I would watch the other children playing tag and feel almost like a normal boy, and it was as if the shadow that clouded my mother’s face had vanished, though that may have been the light from the campfire.

I would usually observe them from a far corner of the garden where our horse used to graze. I was protecting him, because I knew he was afraid of strangers and didn’t like being stroked. He was an English Thoroughbred that had once been a racehorse; my mother had bought him off the knacker. If he saw a saddle, he bucked. When I was small, my mother would sit me on the horse’s back; later I would ride him through the forest, squeezing my thighs to hold on. At night, looking out over the garden from my bedroom, I could hear my mother talking to the horse.

My mother knew every herb in the forest. If I had a sore throat she would make me a syrup of honey, thyme, and onions, and the pain would vanish. Once I told her I was frightened of the dark; she took me by the hand and we walked into the forest at night. She said she couldn’t live with the thought of me being frightened, which troubled me a little, as I was often afraid. Up on the ridgeway fireflies leapt from the branches and settled on my mother’s arms.

Every evening, through my bedroom floorboards, I would hear her coughing. The sound helped me to fall asleep. My parents told me the cancer had stopped growing; the radiotherapy she’d had after my birth had worked. I made a mental note of the word “remission,” though I didn’t know what it meant. Judging by my mother’s expression when she said it, it seemed to be something good. She told me she would die, but no one knew when. I believed that as long as I wasn’t afraid, she would live.

I never played. I spent my time observing the world. In the afternoons I would go into the forest and watch the movement of the leaves touched by the wind. Sometimes I would sit beside my father on the workbench, looking on as he turned pieces of oak, smelling the aroma of fresh sawdust. I hugged my mother while she made white currant jam, and listened to her back when she coughed.

I didn’t like going to school. I learned the alphabet quickly, and I liked numbers, because they were mysterious, but singing songs and making flowers out of cardboard did not come easily to me.

When we started writing stories in German class, I realized that school could help me. I wrote essays about the forest and my mother’s visits to the doctor, and these stories made the world a little less strange to me; they allowed me to create an order I couldn’t see around me. I bought a diary with my pocket money and began to write in it every evening. I don’t know if I was a nerd; if I was, I didn’t care.

There were different groups at school: the girls, the footballers, the handball players, the guitar players, the Russian Germans, the boys who lived in the nice white houses on the edge of the forest. I didn’t like ball games and I didn’t play an instrument; I didn’t live in one of the white houses and I didn’t speak Russian. At break the girls would come over and join me, and when the boys from my class saw this they laughed at me, so at break time I would often go and hide behind a fish tank, where I could be alone.

On my eighth birthday my mother asked the other parents to bring their children round to our house. I sat quietly in front of the marbled cake; I was excited, and wondered whether the children would become my friends. In the afternoon we played hide-and-seek. I ran into the forest and climbed a chestnut tree. They won’t find me here, I thought happily. I stayed up the tree all day; I only came home in the evening. I was proud that no one had found me, and asked my parents where the other children were. My mother told me my hiding place had been too good, and took me in her arms.

All my life my hiding place was too good.

When I was ten, the boys started playing a ball game they’d invented themselves at break, which was so crass and violent that only lunatics or children could have come up with it. The aim was to carry the ball to the other side of the playing field, and you were allowed to use any available means to prevent the other team’s players from doing the same. Once, just before the summer holidays, one of the boys was at home with mumps. They needed another player, and asked me if I wanted to join in. Just thinking about it made me panic, because the children sweated and I didn’t like other people’s sweat; besides, I knew I was terrible at catching. I said no, but they said they couldn’t play without me. I ran up and down the grass for a few minutes, pleased at how successfully I avoided holding the ball. A fellow pupil yelled at me to make an effort or they’d all lose because of me. A few moments later an opponent came running towards me with the ball. He was already in eighth grade and was stronger than me. I’d always been small; this boy played rugby for the regional team and he was running straight at me. Quickly I tried to assess the weak points of the body rushing in my direction, then threw my full weight against his right knee and shattered his kneecap. I knelt beside the boy and told him I was sorry but he barely heard me, as he was screaming very loudly. Later he was picked up by an ambulance and his friends wanted to beat me up, so I ran away, climbed a poplar tree and perched in the small branches right at the top. I was never afraid of falling. The children gathered at the bottom and threw lumps of clay at me that they got from a nearby field.

When I came home I saw my father in the workshop, sanding wood. The principal had already called him. I’d been telling myself the whole time that it wasn’t that bad—after all, nothing had happened to me—but when I saw my father and knew that I was safe, I began to cry. He held me in his arms and I scratched the dried earth from my shirt.

My father was a bit like me; he was often silent, and I have no memory of him playing ball games. In other ways, he was unlike me; he would laugh loud and long, and this laughter had etched lines on his skin. That night, at dinner, he laid two black cowhide boxing gloves beside my plate. He said that things in life were usually gray, not black and white, but sometimes there was only right and wrong, and when stronger people hurt weaker ones, it was wrong. He said he would enroll me in the boxing club the next day. I picked up the gloves and felt the softness of the leather.

At that time, my parents had a visitor for a few weeks: my mother’s half sister from England, who was sitting at the table with us. She hardly spoke any German, and spent most days going for runs in the forest. I liked her, though I couldn’t really understand her when she talked. My mother explained that her half sister had a thunderstorm in her head and I should be nice to her, so each day I picked a bunch of marsh marigolds for her down by the duck pond and put them on the table by her bed, and once I stole an apple twice as big as my fist from a tree by the church and hid it under her pillow for her to find.

I hadn’t had an aunt until I was eight. Then my grandfather died and my mother found out that she had an older half sister living in England.

She had been the result of an affair, and my grandfather had never accepted her as his daughter. After his death, my mother and aunt had somehow managed to become close, even though they were so different, including in their appearance. My mother was tall and her forearms were strong from working in the garden. My aunt was petite, almost delicate, a bit like me, and she had short, buzz cut hair, which back then I thought was cool.

The evening my father laid the boxing gloves on the table, my aunt went on quietly eating her bread. I was a little ashamed that she had seen me so weak, and surprised by the fact that she didn’t seem weak at all, even though she too was small, and had a little patch of scurf on the back of her neck that never seemed to clear up.

Sometimes she would come into my bedroom at night and sit on the floor beside my bed. Now, when I can’t sleep, I occasionally look down at the floor and for a moment, if I turn my head very fast, it feels as if she’s still sitting there.

That particular evening she spent a long time sitting on the bare floorboards, just looking at me. I was a little frightened, because what she was doing seemed strange. She took my hand and held it tight; her hands were like a little girl’s.

She spoke to me in German, better than I expected; her accent was a bit funny, but I didn’t laugh.

“When I was your age, it was the same for me,” she said.

“Why?”

“No father.”

“Was that a reason?”

“It was back then,” she said.

We sat like that for a long time. I imagined how terrible life must be without a father, and stroked my thumb across the back of her hand.

“Did the others hurt you?” I asked.

With a sharp intake of breath, she squeezed my hand a little tighter and said something I’d never heard anyone say before:

“If they touch you, come and find me, and I’ll kill them.”

Alex

He was so naïve. And had these fascinating soft eyes, as if he were always worried, and as if there were a black galaxy hidden in each eyeball. I’ll never forget his face that night. He doesn’t know it, but back then Hans was one of the few things that kept me alive.

On one of the days when the sun didn’t rise I saw him in the garden, sitting on the grass, and I went and sat next to him.

“How are things?” I asked.

His black hair was thick, like an animal’s. He sat there beside me, and I sensed in him the same heaviness that numbed me by day and kept me awake at night.

“I’m sad, Aunt Alex,” he said.

I would have liked to put my arm around him, but didn’t dare. For a long time I thought that if I got too close to people they might catch my bad thoughts, like Spanish flu.

He was like the water in the forest, gentle and quiet. I had to look after him. My sister couldn’t; she was raising him with kisses. What good did it do him if she kissed away his tears when the children at school wanted to beat him up?

Sometimes I would secretly watch him at boxing training. I would stand behind the door to the gym and watch through the yellow-tinted glass. I never wanted children, and I wouldn’t have been a good mother; nonetheless, when I saw this boy standing between the dangling punch bags, trying to find the strength to hit them, I was touched. He would be able to protect himself if someone showed him how.

Hans

Evening light slanted across the gym; the punch bags hung on chains suspended from the ceiling. After training I would sit in the car, steam rising from my shirt. My father would have been watching, and we would both sit there in silence. I could see that he was happy; at least that’s what I thought at the time.

Four times a week he would take me to training and watch. Afterwards my mother would cook us fried potatoes with onions and gherkins, which she called a “farmer’s breakfast.” When I was grown up I made it myself a couple of times, but it didn’t taste the same.

A few weeks later the boys at school wanted to beat me up again. This time, too, I ran away, but then I thought better of it and stopped. I turned and raised my fists, the way my boxing coach had shown me, the right one beside my chin, the left at eye level in front of my head. No one attacked me.

I trained until the capsules in my knuckles ached. To me, boxing was different from other sports because no one expected me to enjoy it, and I could be alone with my pain, my strength, my fear. I was closer to other boys when I was boxing than I had ever been before. When we practiced sparring at close range I could smell their sweat and feel the heat coming off them. It bothered me, and to begin with I often felt nauseous, but I got used to it. Now, when I look back at that time, I think I only became able to tolerate other people when I started to fight them. I preferred to box at a distance, from long range, keeping my opponent at arm’s length.

At thirteen I fought my first match and lost on points. I remember that, though I don’t recall my opponent. My father was at the ringside. In the car he kissed my knuckles and said he’d never been as proud of anything as he was of me. I remember that clearly.

One November day, when I was fifteen, we were driving to Brandenburg for a tournament. On the way there, on a bridge over the Havel just outside Berlin, there was a sheet of ice on the road. Our car skidded on the bend and slid into the crash barrier. My father got out and walked towards the traffic coming up behind us so no one would plow into the car with his son in it. I stayed in the passenger seat and was afraid. In the rearview mirror I saw a cement truck with a flashing sign on the windshield that said HANSI. The radiator of the truck hit my father and split him in two. The cement truck was slightly dented. I don’t remember the funeral, or the months that followed.

Six months later I found my mother lying in the garden. She was outside because I’d asked for chives to sprinkle over my scrambled egg that evening. Her movements were slow; there was a glint in the corner of her eyes, and beside her lay a little basket of the fresh chives she had cut for me. She gazed at me. I thought she looked beautiful.

I called the ambulance, then sat beside her in the grass and listened as the rattle in her lungs grew fainter. Her grip on my hand remained firm even when her breath fell silent. The autopsy found that she had died from a honeybee sting; the venom had triggered anaphylactic shock.

The coffin was made of cherrywood. My father had built it years earlier in accordance with my mother’s wishes and had carved flowers all over it. People threw earth into the grave with a little trowel. My mother’s half sister was wearing a white dress; she reached down, took some earth in her hand and dropped it onto the coffin. That made an impression on me. I thought of how my mother used to kneel in the garden picking strawberries, and I too took a handful of earth.

My father had died because I wanted to box in Brandenburg. My mother had died because I wanted chives on my scrambled egg. For a few days I waited to wake up from this nightmare, and when that didn’t happen I became filled with a darkness so overwhelming I’m astonished that I survived.

After the funeral my aunt spoke to me in English; she was crying, and her left eyelid fluttered with every word. I didn’t understand her. I couldn’t cry; I wanted to scream, though I had never screamed before.

There was a cross behind the altar in the church. I went to look at it. The Jesus who hung there looked indifferent. I took off my suit jacket and punched the church wall with my fists until my left metacarpal broke at the base of the little finger.

Alex

Goya went deaf in early 1792. He’d had a fever, and became so ill that he lost his hearing. Afterwards he moved to a villa outside Madrid, where he painted fourteen pictures on his dining-room and drawing-room walls. Goya didn’t name these pictures. He is assumed to have painted them for no one but himself. They are known as the Pinturas negras, the Black Paintings. I think it’s a beautiful name.

Dark, disturbing works, full of violence, hatred, and insanity. They’re works of genius, but they’re hard to look at. One of the paintings depicts the god Saturn devouring his son because of a prophecy that one of his progeny would overthrow him. Some say Goya’s deafness made him go mad. There is madness in the eyes of the god in that picture.

Is it part of my illness when I feel that pictures speak to me, or do other people feel the same?

Madness was already part of my life when my sister died. It’s easy for me to admit this, because it explains a lot. The doctors didn’t call it that; they talked about dissociation and trauma, but I know that I was grappling with madness. I had to vanquish it alone. If I’d taken Hans in I would have destroyed us both. The dark thoughts would have infected him. I knew what it was like to grow up without a stable family, and I couldn’t have provided that stable family for him. At boarding school he was safe.

They broke Goya’s picture of Saturn off the wall, and now it hangs in the Prado. Everyone raves about the eyes, but they’re not the crucial thing. The crucial thing is a section that was painted over because people would have been too distressed by it. I’ve examined that painting very closely. Under the dark patch that covers the god’s nether regions you can make out that Goya painted him with an erect penis.

I would have dragged the boy with me into the abyss. I wasn’t ready yet. I wasn’t myself.

Hans

Our horse was taken away, and I was sent to boarding school. My aunt became my legal guardian; I thought she would come and fetch me, but she didn’t. I didn’t dare ask her why she decided not to. She sold our house in the forest and used the money to pay for the Jesuit school. In the brochure it said: “Order and decorum in everyday life are essential, along with respectfulness and the willingness to help one’s fellow man. We ensure that each individual pupil is guaranteed a well-regulated boarding school environment in which he is motivated and willing to learn.” This sentence made me uneasy.

My suitcase contained five pairs of trousers and five shirts, underwear, socks, one of my father’s woolen jerseys, my mother’s necklace, a hat, a twig from the cherry tree, my brown diary with the unlined pages and the black cowhide boxing gloves.

Johannes Theological College was situated on the slopes of the Bavarian Forest; it looked to me like a knight’s castle, with its towers and crenellated walls. For centuries it served the Jesuits as a place of retreat, and in World War II some members of the resistance group known as the Kreisau Circle met here to plan the murder of Adolf Hitler.

When I saw the boarding school for the first time, the sun was shining through the fir trees and the mountain breeze blew Italian warmth into the countryside, but this was just part of the deception.

On my first day at boarding school I visited the principal’s study. He was a friendly young man; we sat at a table covered with a linen cloth. I gripped the cloth under the table and thought of my mother’s yellow dress.

The principal said he understood if I needed time, but I knew that he didn’t understand a thing. He had a wart on his forehead and smiled, although there was no reason to do so. I wondered why he was taking notes.

At Johannes Theological College every pupil had to give a urine sample on Monday morning, which was tested for narcotics. The pupils were either the sons of rich businessmen or boys who had taken so many drugs their parents thought the monks would be better equipped to deal with them.

Twelve monks lived in the castle; eleven taught, and one was a cook. His name was Father Gerald and he was from Sudan. I liked him because he was different and had a sad smile. Father Gerald didn’t talk much; when he did, it was in English, and his voice sounded deep and foreign. When he cooked, he boiled everything for too long.

On the first day I went to the washroom and looked at the basins hanging all along the wall. I counted them: there were forty. Everyone here seemed to live on an equal footing. That night a few of the pupils threw balls of paper at me, chewed into compact projectiles. I pretended not to notice. Later they stole my pillow. After a few weeks, an older boy slapped the back of my neck with the flat of his hand as I was queuing in the dining hall. I felt my ears turn red. I grinned, because I didn’t know what else to do; it only hurt a little. The boy stood behind me and asked loudly if I missed my mama, and if that was why I always whimpered in my sleep at night. I turned and punched the boy in the face with a left hook. The impact made a sound like the opening of a jam jar.

Father Gerald saw it all, and grabbed me by the arms. I thought I’d be expelled from the school, and I was glad, because I hoped that meant I’d be able to go and live with my aunt in England. I didn’t know that the school needed the money because some of the monks had invested in Icelandic high-tech companies and had lost a lot of the foundation’s capital. Also, the boy I’d hit was a troublemaker and the principal was secretly glad that he was in the sick bay. He made me reorganize and clean the wine cellar as a punishment.

After the punch-up the other children avoided me. I let them copy my math homework, and once, after spending days summoning up the courage, I asked if anyone wanted to play hide-and-seek in the forest. I resolved not to run as far away this time, but the children weren’t interested in me and said playing hide-and-seek was childish. Perhaps I need to tell them more about myself, I thought, so I told them how oranges tasted of adventure, and how the soft hair at the nape of girls’ necks sometimes looked like candyfloss. They just jeered at me.

One of the monks told me I shouldn’t pay any attention to the fact that I was poorer than the other pupils. He gave me a Bible with a silk bookmark indicating a passage of Job in the Old Testament: the Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord. I climbed the church tower and flung the Bible into the Bavarian Forest.

I stayed sane because I was able to spend time alone, which for the most part I enjoyed. I read and went for walks in the forest and tried to identify the birds. I became good at that.

Once, when we had been studying the Book of Genesis in religious education yet again, I thought about which hundred people I would save if the world were about to end. I couldn’t think of one hundred people who deserved to go in the ark, but I would have filled the boat anyway, with Father Gerald’s extended family. That wasn’t what preoccupied me, though. What first troubled me, then filled me with sadness, was the realization that there was no one who would let me onto their ark.

I missed my parents, and I missed the house, the smell of the old floorboards, the furniture my father had made, every corner of the cool walls that held a memory for me. It was like the hunger I used to feel when I wasn’t allowed to eat before one of my boxing matches because I had to lose two kilos to reach my weight class. The hunger was a hole I felt in my stomach. The loneliness was a hole I felt in my entire body, as if all that was left of me was an empty husk.

To begin with, my aunt wrote me a letter once a month, in English, in which she mostly told me what was happening at her university. I wrote her long letters about the noises in the dormitory, and the other children, and how I dreamt about my father without a face, but she never responded to this.

The wine cellar I was supposed to reorganize as a punishment was long and cool. Every now and then I threw a few punches in the air. I hadn’t asked if I could carry on boxing at boarding school. The gloves were stowed in the suitcase under my bed. I took off my shirt and shadowboxed until the sweat poured from my fists, dripping onto the bottles as I punched.

A shadow moved in the darkness. “Your left is too low.”

I stared at the monk. I’d be in trouble now. Father Gerald in his black cassock was almost invisible in the dark of the cellar.

“You drop your left,” he said. He held up his right palm like a punch mitt. Seeing his stance, I knew that Father Gerald was a boxer. I hesitated for a moment, then stretched out my left arm and touched the pale-pink palm with my fist.

Father Gerald took a step back and raised both hands. I punched: left, right. The priest described a hook. I ducked. From one combination to another the pace of the punches increased. The sound of fists on palms echoed through the wine cellar, the rhythm of a language that needed no words. At the end Father Gerald let me hit three hard punches with my right. He winced, then laughed.

“Call me Gerald.”

“Hans.”

It was the first time in ages that I’d spoken because I wanted to.

“Thank you,” I said.

The next day I put my boxing gloves in a rucksack and took them with me to the wine cellar. Father Gerald had brought two small, hard sofa cushions; he had used a filleting knife to cut holes in them for his hands. They were the softest mitts I would ever hit.

“Let’s go,” said Father Gerald.

Hans

The months at boarding school passed me by. When I wasn’t in the wine cellar I spent a lot of time sitting in the tower next to the chapel bell, because there I could read undisturbed. Sometimes I would gaze at the edge of the forest and dream about how I would start a better life there when I finished school. Every hour a monk would pull on the bell rope down below, the bell would ring, and I would press my hands to my ears.

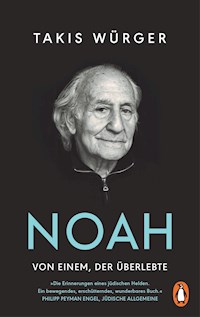

Then I received a letter with two mauve stamps displaying the profile of Queen Elizabeth II. My name was written on the envelope in small letters, a soft, round handwriting I knew belonged to my aunt. Her letters weren’t affectionate, but they still made me happy because they were the only ones I received.

Twice, early on, I had spent the holidays with Alex in England, but she had worked all day and when we sat at table in the evening, drinking warm beer, she had cried a lot. She put beer in front of me on the table every night, as if that was normal, and apologized when she cried.

I didn’t visit her again after that. I spent bank holidays and the whole of the summer with the monks. At boarding school I had a library full of books, and boxing lessons with Father Gerald; it wasn’t much, but it was better than an aunt who made me feel like the loneliest person in the world.

This letter was written on pale brown paper. It was too short, and in English.

Dear Hans,

I know: I haven’t written to you for a long time. I hope you are happy. I would like to invite you to visit me in Cambridge. There’s something you might be able to help me with. I will take care of your travel expenses.

With best wishes,

Alex

I read the letter again and again, and each time I got stuck on the sentence There’s something you might be able to help me with.